- Research remains inconclusive about the effects of exclusionary practices like suspensions on a disciplined child’s peers. —Education Week

- Since the pandemic, nearly every state has seen improvements in math achievement, but reading gains remain largely stagnant. —Chalkbeat

- Despite its elitist reputation, classical education seeks to provide an aristocratic education to everyone. —National Affairs, Micah Meadowcroft

When former mayor Bill de Blasio promised to dismantle New York City’s gifted education programs, then-candidate Eric Adams laudably promised to save, reform and expand them. Since taking the helm, however, his actual policies and actions deserve scant praise—middling improvements paired with major regressions.

Earlier this year, for example, the Adams team expanded the number of sites for gifted education at the elementary level but scrapped the use of tests as a screening component—despite ample research supporting their use—and made school grades the sole determinant for inclusion. It then set the standards so low that two-thirds of students qualify for services, making the eligible range of achievement levels so wide that the programs are now “gifted” in name only: They can no longer feature the increased pacing and rigor that makes gifted education worthwhile.

Taken together, hizzoner’s changes have transformed gifted education in the lower grades into a glorified lottery based on the wrong measures, with students earning the best grades no likelier to win seats as those who barely make the cutoff.

As for high schools, the mayor did great work by creating three new selective schools that will open this fall—reducing needless scarcity. But that work is incomplete, as demand still far exceeds supply, forcing lotteries to operate here, as well.

To Adams’s credit, he clearly recognizes how much we risk if we’re cavalier with the education of America’s top-performing students. He understands that we need advanced learners to be highly educated to ensure our long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation. He also inherited a situation that was confusing, contentious, and headed towards abolition. Resurrecting it alone warrants applause—and may reverberate elsewhere.

Because of its size and cultural footprint, New York City models policy for countless other school systems, directs curriculum and textbook sellers, and influences education debates around the country.

And our country is in need of a stellar model in the realm of advanced learning. Years ago—immediately following Sputnik, for example—the U.S. took it seriously. But half a century of education policies have shoved it to the side, even to a place of skepticism and derision. Only two-thirds of districts offer any such programming, for instance, and in many places that do offer it, services are nothing more than meager supplements that are unlikely to make much of a difference in their students’ achievement, and are staffed with teachers who have not been trained to educate bright students.

In pursuit of a roadmap for districts across the land to do a better job of educating their advanced learners, a working group of diverse education experts—including one of us—convened last year to develop a report that summarizes the research on gifted education and recommends best practices. Its analysis suggests that New York City faces three big but solvable problems in this realm: the process for screening students is prone to bias and error, the programming in the city is needlessly all or nothing, and gifted services are far too scarce.

To solve problem one, the city should screen every single student in its schools using not only teacher-conferred grades, but also data from state standardized tests. Doing this in every grade for every child, instead of relying on a single age-based screening point that students must opt into, is an empirically-grounded method to identify intellectually gifted children from all strata of society.

For problems two and three, Adams should expand the number of seats at the elementary level, open more selective high schools, and mandate that every middle-school pupil in the city has access to advanced learning opportunities. In place of the city’s current dichotomous, you’re-in-or-you’re-out system where selective schools serve only a selective few, offer a “continuum of services”: separate schools or classrooms will be best for certain students, for example; in-class achievement grouping will suffice for others; and some should skip entire grades.

Mayor Adams is on the right track and deserves praise for rescuing advanced education from the abyss. They no doubt hope to eventually construct a gifted education system that serves every advanced student. But in its current form, the system falls short.

Data show that America’s current manufacturing workforce is aging and retiring as the sector is expanding exponentially and its demand for workers outpaces supply. Thus, a new report from the RAND Corporation looking at the career and technical education pathways designed to take postsecondary students directly from the classroom to the manufacturing floor is especially timely. It expands the research in this understudied area, focuses on efforts in Fordham’s home state of Ohio.

Data come from the Ohio Longitudinal Data Archive, drawing on information from the state’s higher education institutions and technical colleges, as well as from state unemployment insurance records. Student records include when each student first enrolled in a college or program; the duration of their enrollment; the program type, courses taken, and grades; whether and when the student earned a degree; and the type of degree earned. The technical college records are similar but include a course-based proxy for specific credentials earned. The data cover postsecondary enrollments and degrees earned between 2006 and 2019. The unemployment data cover 2007 through 2021, and all wage estimates are presented in 2021 dollars. To delineate “manufacturing-related” programs—the specific focus of their analysis—from other career and technical courses, the researchers use Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes. As you might imagine, the list is heavy on engineering, construction, metalwork, and plastics courses.

In 2019, more than 30,000 students were enrolled in manufacturing-related postsecondary programs in Ohio. Approximately 1,600 were enrolled in technical colleges, 13,500 in associate degree programs at traditional two- and four-year institutions, and 13,800 in bachelor’s degree programs at those institutions. Interestingly, the previous decade showed a sharp decline in the number of students pursuing associate degrees and a steady rise in the number pursuing bachelor’s degrees. Technical college enrollment remained largely flat during that time. In terms of completion, approximately 7,700 students earned a manufacturing-related credential in 2019. Not surprisingly, given the enrollment trend, the largest share earned a bachelor’s degree. The number of completers at technical colleges was down against its high point a few years earlier. That total number also includes individuals who earned a manufacturing-related certificate independent of formal higher education settings (adult apprenticeships, formal upskilling by current employers, etc.), which nearly equaled the associate degree completers. In short, Ohio’s manufacturing employers should have been swimming in applications from skilled employees.

Data show that 82 percent of those who completed a technical college program were employed within a year of completion, compared to 84 percent of those who completed a certificate, 83 percent of those who completed an associate degree, and 65 percent of those who completed a bachelor’s degree. Those percentages remained fairly strong for up to five years post-completion, indicating that degrees and credentials are valuable to their recipients. However, a much smaller share of those credentialed individuals were primarily employed in the manufacturing sector. To wit: Just 38 percent of those who completed a technical college program were employed in Ohio manufacturing at one year post-completion, compared to 27 percent of those who completed a certificate, 25 percent of those who completed and associate degree, and 30 percent of those who completed a bachelor’s degree. Those percentages also remained similar after five years.

Where were they going instead? Construction, retail, technical services, administrative/support, and waste management/remediation services were the biggest recipients of manufacturing-credentialed workers in 2019, with a perhaps-predictable differentiation in professional versus service employment based on whether workers earned bachelor’s or sub-bachelor’s degrees or credentials. The attrition does not appear to be driven by industry pay gaps, as Ohio’s manufacturing industry pays higher wages than do other industries into which credential-earning workers opt. White males are more likely than females and non-white men to move directly from credential to employment, both in manufacturing and non-manufacturing jobs, and their wages are higher, as well.

The bottom line seems to be that even with a fairly clear pathway from the graduation stage to the factory floor, Ohio needs more newly-credentialed individuals to take that step, especially if a more-diverse manufacturing workforce is desired. Unfortunately, that is easier said than done. The report suggests geographic concerns (too few manufacturing jobs in the local areas where students are graduating) and skill mismatches (credentials earned are not the ones local employers need) as prime areas where gaps could be addressed. It is to be hoped that as the Silicon Heartland takes root and expands outward from central Ohio, the new and growing manufacturing presence here will bring on a concomitant effort to reach into the education world and help shape existing training and credentialing programs to their needs, to build new ones as needed, to welcome nontraditional employees, and bridge any gaps or mismatches between school and work.

SOURCE: Lisa Abraham, Christine Mulhern, and Lucas Greer, “Strengthening the Manufacturing Workforce in Ohio,” RAND Corporation (August 2023).

Ohio Charter News will be taking a two week vacation break after today – returning on October 20.

The biggest news

Last week, Nina Rees, President and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter School, announced that she would leaving the helm of NAPCS in December. “Since I joined the National Alliance,” she wrote in her departure announcement, “the number of students attending charter schools has grown from 2.3 million to 3.7 million. The number of states with charter school laws has expanded to 46. And vitally, annual funding for the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP)…has expanded by roughly 75 percent to $440 million.” She added: “Reshaping institutions is difficult work, and I am heartened by the scale and reach of the change we have delivered during my tenure.” Kudos, Nina. You will be missed!

Looking back

Following that announcement, Nina Rees sat down with Fordham’s Mike Petrilli on the Gadfly Podcast to talk about her 11-year tenure, the ups and downs of charter schools, and the state of the sector today. Essential listening.

Positivity

In Ohio, it seems that we may be turning a corner when it comes to the perception of charter schools by the general public. Decades of perseverance, growth, success, and community connection can do that, I suppose. For one example: Take a look at this great newspaper coverage of Horizon Science Academy Lorain’s recent International Night. Students and staff showcased their diverse cultures through performances, music, and art. Meanwhile, Horizon Science Academy Youngstown was lauded by local TV news for its participation in a Saturday program that uses kickboxing to help students develop in and out of the classroom. “We’re teaching the kids to push their limits, to do certain things different,” said coach Jason Ray. “If I keep my grades up, then I’m going to be able to go to any high school,” said one eighth-grader in answer to the question of what he’s learning besides how to kickbox. The hard work and perseverance he is demonstrating in class, he says, is “going to lead me out of college with good grades.” Nice!

Team Positivity

Speaking of the connection between athletics and education, here’s another great story about the recent grand opening of Springfield Sports Academy. While this coverage highlights the connection between the school and local football phenom Braxton Miller, as others have also done, it’s the comments from school leaders that stand out this time. “They’re going to receive as much, if not more academic time than any traditional public school,” said Accel Schools Executive Vice President Chad Carr. “It’s just that we have streamlined it in such a way that we’re able to incorporate their team sport into the school day.” Nice. Principal Travonna Hunter (also a Springfield native) added: “We’re going to be respectful and ready, we’re going to be authentic, we’re going to be accountable, we’re going to be committed to excellence and really try to show every day that we’re giving our best effort.” Good luck to all for a great rookie year!

Not all the news can be good

Sadly, several school districts in northwest Ohio continue to struggle with properly transporting students nearly two months into the school year. Lots of reasons are put forth in this coverage, with at least part of the blame put on the state’s requirement for districts to transport charter and private school students every day. Not put forth: Any sign of a solution.

Mixed bag

Fordham’s Aaron Churchill this week published a look at charter and district report card results for Ohio’s eight largest urban areas. Among his big picture takeaways: Despite some positive outcomes in reading and ELA, there remains much work for all schools to help urban students get up to grade level in all subject areas, and the Progress and Overall ratings available on the report cards appear to be great indicators of quality for school-shopping parents (as well as policymakers and community members) to pay attention to.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- Our own Chad Aldis was a guest on recent episode of Ideastream’s The State of Ohio Show. In it, he is quizzed on several aspects of the EdChoice voucher expansion, Fordham’s past research on EdChoice, and the voucher grouchers’ pending lawsuit. (State of Ohio, Ideastream, 9/22/23)

- Cleveland.com columnist and editorial board member Eric Foster has some powerful thoughts on what needs to change in education in northeast Ohio following another disastrous report card showing for too many schools and districts up there. It’s important stuff, fully informed by his own life experiences. Will anyone hear him? (Cleveland.com, 9/27/23) Relatedly, officials in Youngstown City Schools are, in my own opinion, eking far too vigorous a celebration out of the meager positive notes in their own report card. Taking a cue from Mr. Foster’s opinion: Students there are not well-served by your premature claims of improvement. (Vindy.com, 9/27/23)

- You can now add Toledo City Schools to the list of completely blinkered Ohio districts closing their doors for the entire day on April 8, 2024. There will be a rare solar eclipse visible in parts of the state that day. At 3:10 pm. For about 8 minutes. But instead of extending the school day and embracing the once-in-a lifetime science learning opportunity dropped in their laps free of charge, our schools (and the public safety officials advising them) are acting like end-of-the-world nutters who would prefer everyone to hunker down in their homes rather than have to chance a bit of heavy traffic and the possibility of spotty wi-fi. The horror! (Toledo Blade, 9/28/23)

My very observant long-time subscribers (kveðjur to all tólf of you!) will surely have noticed a countdown theme in our headlines this week which had nothing to do with the stories covered. Here’s why: Gadfly Bites is going on a big vacation, starting today. Your humble clips compiler will be off-the-grid (on ice, or á ís as some folks say) for two weeks. Returning on Monday, October 16. I reckon we’ll have plenty of news to snark about. See you then!

Your humble clips compiler—Jeff Murray ([email protected])

This nation’s economic security will be won or lost based on the ability of elementary schools to energize science education.

That is because the country is at the start of a massive effort intended to bring semiconductor manufacturing to the Southwest, battery research and development to rural upstate New York, and more. It’s an effort that promises to spread good-paying jobs to parts of the country that haven’t benefited from them in recent decades.

More semiconductor manufacturing, more engineering jobs, more tech jobs—over the next ten years, these and other jobs in STEM fields are projected to grow faster than all others combined, with twice the median salary. More STEM jobs means the country needs more STEM-ready students, and that means helping elementary schools engage children with a rich and energetic brand of science before sixth grade, when children often start forming career aspirations.

This is particularly critical in rural areas because if children in these communities don’t have a science-rich education, they will be less likely to be interested in or qualified for the STEM jobs coming to their regions. And if that’s the case, the purpose of locating these jobs there will be undermined, as employers will have to recruit qualified workers from other parts of the nation or world.

Getting young Americans involved in science now in a way that captivates them early in their education will prepare them to fill the STEM jobs of the near future and build the foundation for a strong and prosperous economy.

When children from all backgrounds see themselves as scientists, society reaps the benefits. But researchers estimate this country has missed out on generations of “lost Einsteins” because many lack a relevant and relatable science education starting in elementary school, and kids cannot be what they cannot see.

The 2018 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education found that students in kindergarten to third grade learned science for an average of just 18 minutes a day—less time than many of them spend on the school bus. The results of that are clear: Only 36 percent of fourth graders tested as proficient on the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress science exam.

If the new approach to industrial policy and STEM jobs is going to succeed, that has to change. Science education must start early because children develop their interests and passions early. And it must attract all kids, no matter their backgrounds, resources or experiences.

The way to do that is to move students from learning about science from behind a classroom desk to exploring the world outside and around them—whether that’s studying drainage and flooding in an urban area or finding the angle of the sun to determine the best placement of solar panels in a rural community. Children’s minds come alive to science when they see it in every part of their world. They respond to active learning environments that offer the opportunity to collect data, test and solve problems in real time. The organization I lead, Out Teach, transforms school grounds into real-world labs. Last year, we brought science to life for 53,000 students and 188 schools in seventy-seven communities, starting in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and now extended to historically underserved areas of Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, and Washington, D.C.

These learning stations take teachers and students out of the classroom and into the outdoors, where they can study the growth of plants or crops, build landforms to gauge erosion by pouring water on it or use plastic bags to find hidden water through leaf transpiration.

Children make the connection between the science they see in their schoolyards and the relevance of it to their own communities.

As a Mississippi native who now lives, works, and parents in Washington, D.C., I know that kids in rural areas grow up, get educated, work, and live differently than those in cities or suburbs. High-speed internet, for example, is not a given. Technology and office work are not the norm. Some schools don’t have the funding, facilities, teaching staff, labs, even textbooks that are taken for granted in many parts of the country. Almost one in five public school students attend a rural school, yet policymakers rarely address rural needs. Nonprofits and social service agencies often fill gaps in urban and suburban areas, but less so for rural schools. Indeed, the most robust voice for rural schools, the Rural School and Community Trust, no longer has an active website—a metaphor for the isolating lack of broadband internet or reliable cell service that confronts many rural schools.

For generations, those differences did not affect the nation economically. But now, they matter a lot. Modern society and the modern economy rely more on strong scientific readiness in places like the Southwest and rural upstate New York than ever.

The $80 billion in investments that Congress and President Joe Biden have made are designed to share the wealth of economic growth in every part of the country, not just Silicon Valley, Wall Street, and the suburbs of Washington, D.C. Mining that wealth can’t happen, however, unless every school—rural, suburban, and urban—has the facilities and a plan to get young children involved in science.

If this new industrial policy is to succeed in making this country economically sound and secure in the wake of the pandemic, engaging all citizens is critical. Making science real and relevant is, in that sense, a national economic security initiative. This opportunity is too crucial to miss.

Editor’s note: This was first published by The 74.

Academic Distress Commissions (ADCs) have a long and controversial history in Ohio. They were first created in 2005 as a way for the state to intervene in districts that consistently failed to meet academic standards. The law was significantly strengthened in 2015, and was promptly met with immediate and fierce pushback from district advocates. By 2021, lawmakers had caved to political pressure and created an easy off-ramp for the three districts that were under ADC control: Youngstown, Lorain, and East Cleveland. This off-ramp was pitched as a compromise—control of the district would return to the local school board and its chosen superintendent, but in exchange, they would be tasked with developing academic improvement plans containing annual and overall improvement benchmarks. ADCs would be permanently dissolved if districts met a majority of these benchmarks by June 2025 (previously, districts had to achieve state-defined performance targets to exit).

Official implementation of these plans began during the 2022–23 school year. State report cards for that year—the report cards released earlier this month by the Ohio Department of Education—were meant to be the first check-in on how things were going under these new improvement plans. Thanks to the state budget enacted at the end of June, though, things are a little more complicated. That’s because the budget contained a tiny provision that dissolved Lorain’s ADC and its academic improvement plan. As a result, Lorain is no longer required to demonstrate that it’s improving on behalf of its students. Its counterparts in Youngstown and East Cleveland, however, didn’t benefit from the same carve out.

This tiny change sets up a hugely interesting comparison. This year’s state report cards are no longer a simple check-in. Now, they’re an opportunity to compare the district that state leaders deemed worthy of an academic free pass—Lorain—to the other two that weren’t quite so “lucky.” Below is an examination of each district’s results in four of the report card’s most significant areas: achievement, progress, early literacy, and chronic absenteeism.

Achievement

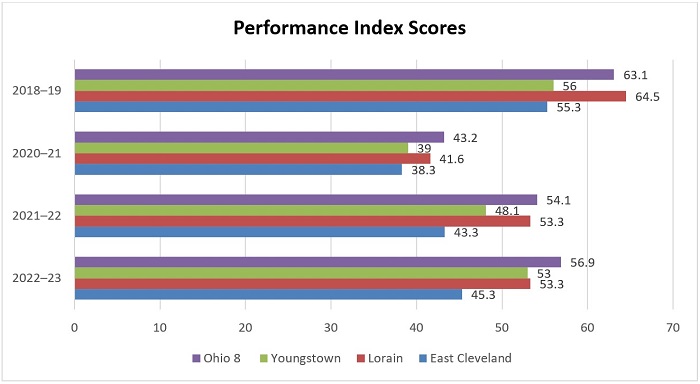

Achievement is the only test-based report card indicator that appeared on each of the three districts’ improvement plans. Specifically, the plans focus on performance index (PI) scores, which measure the state test results of every student and award districts points based on the state’s six achievement levels. The higher a student’s achievement, the more points the district earns. For example, a student who scores at the advanced level earns their district 1.2 points, while a student testing at the basic level (just below proficient) earns 0.6 points.

The chart below depicts performance index scores in ADC districts, with averages from the Ohio Eight urban districts included for comparison. It’s important to remember that the PI calculations award zeros when students do not participate in state assessments. The number of untested students was significantly higher in 2020–21, the height of pandemic-related disruptions and school closures. That—combined with learning loss—depressed some districts’ PI scores that year.

Figure 1. Performance index scores, 2018–2023

Results from the 2021–22 school year indicate the beginnings of an academic bounce back. The Ohio Eight average and results from the three ADC districts are all higher than the year prior. Based solely on these data—which are what lawmakers had available to them during the budget cycle—Lorain was outperforming the other ADC districts and closing in on the Ohio Eight average. Perhaps advocates from Lorain used this as evidence that they were worthy of receiving an early release from state oversight.

But struggling districts need to prove that they’re getting better over time. That’s why the ADC off-ramp that was put into law in 2021 required districts to implement an improvement plan and track results through June 2025. Unfortunately, lawmakers decided that didn’t matter for Lorain. And now, report card results from 2022–23 have revealed that Lorain hasn’t continued improving. In fact, its performance index score is flat compared to the year prior, while scores ticked up statewide and in the other ADC districts. East Cleveland’s score went up slightly, while Youngstown’s jumped by five points.

Progress

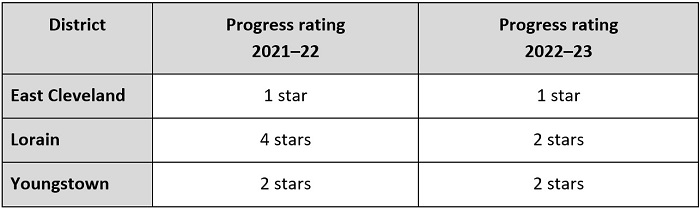

Ohio’s progress component measures the academic growth students make over the course of a year. This measure is crucial, as it showcases a district’s or school’s contribution to student learning while yielding results that are closer to neutral with respect to schools’ demographics. Even in districts where students are far behind in reading and math achievement, the progress component can reveal positive academic growth.

The table below breaks down the progress ratings of each ADC district for the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. East Cleveland and Youngstown remained poor performers at just one and two stars, respectively, in both years. Their lack of growth should be a red flag, as a consistent four- or five-star rating is needed to close achievement gaps. But Lorain’s rating should also cause concern. In 2021–22, the district earned four stars. That meant students made more progress than expected. But in 2022–23, its progress rating dropped to two stars. That means students made less progress than expected. In the time span of one year—the same year that lawmakers decided Lorain had done enough to earn a free pass—the district’s progress rating dropped from positive and promising to negative and discouraging.

Table 1. Progress ratings for ADC districts 2021–22 and 2022–23

Early literacy

Ohio is on the cusp of a significant early literacy overhaul centered on the science of reading. This overhaul makes results on the early literacy component even more important than usual, as results from 2021–22 and 2022–23 will offer a baseline against which to compare future results.

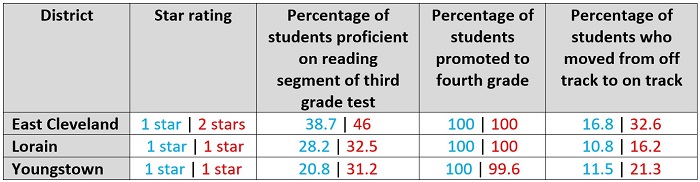

The table below breaks down the early-literacy results for each ADC district. Results for 2021–22 are shown in blue, while those for 2022–23 are shown in red. Once again, Lorain is not the ADC district that performed best. That would be East Cleveland, which earned two stars overall and had nearly half of their third graders score proficient on the reading portion of the state test. By comparison, Lorain and Youngstown earned only one star and had just one-third of their third graders score proficient. Perhaps most troublesome are the results indicating that Lorain moved just 16 percent of its students from off track to on track in reading. Youngstown, on the other hand, moved 21 percent of its students, while East Cleveland doubled Lorain’s total and moved 32 percent. Also of note are the universal promotion rates of all three ADC districts: Without a retention requirement, they waved through practically all third-graders to fourth grade regardless of whether they were prepared to succeed there.

Table 2. Early literacy scores for ADC districts 2021–22 and 2022–23

Chronic absenteeism

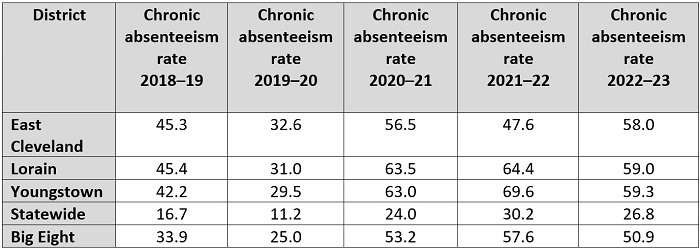

Chronic absenteeism has been a hot topic in Ohio as of late, and rightfully so. Student absences have soared in recent years, and have become a prominent roadblock in Ohio’s efforts to mitigate pandemic-caused learning loss and improve student outcomes. Fortunately, Ohio has tracked chronic absenteeism data on its state report cards since 2017. As a result, we can examine chronic absenteeism rates in all three ADC districts over time, and compare them with the statewide average and the average in the Ohio Eight.

As the table below demonstrates, student absences skyrocketed once the pandemic hit. Chronic absenteeism rates during the 2021–22 school year were particularly bad, but two ADC districts had truly appalling numbers: Lorain had a chronic absenteeism rate of 64 percent, while Youngstown had a rate of 69 percent. Those rates got better during the 2022–23 school year, but are still well above 50 percent. East Cleveland, meanwhile, saw its absenteeism rate rise significantly this year.

Table 3. Pre- and post-pandemic chronic absenteeism percentages

***

There is one more crucial report card measure worth mentioning: overall grades. This measure takes into account all of the report card components and combines them into a concise, easy-to-understand measure of district performance. Unsurprisingly, overall grades from ADC districts are not inspiring. Youngstown, which outperformed Lorain and East Cleveland on several measures, was awarded 2.5 stars. Lorain and East Cleveland were each awarded two stars. These results are even more concerning within the context of the overall distribution of scores across the state. Only fourteen of over 600 districts were awarded two stars, and another forty-six were awarded 2.5 stars (just one district received one or 1.5 stars). That puts Lorain and East Cleveland in the bottom 2 percent of districts statewide and Youngstown in the bottom 8 percent.

District advocates will likely argue that this is only one year of results, and that it’s going to take time for ADC districts to work themselves up from the bottom of the barrel. But that was the whole point of the ADC transition plan established in 2021. Chronically-underperforming districts were given a timeline and standards (albeit questionably low ones) against which they were expected to improve. They were even provided with the local control they demanded to do so. After one year, that local control hasn’t yet seemed to benefit students. In fact, in Lorain, things have gotten worse. And yet, Youngstown and East Cleveland are still under state oversight and Lorain is not. To be clear, this doesn’t mean that Youngstown and East Cleveland also deserved special treatment. It means that lawmakers should have resisted political pressure and insisted that all three ADC districts prove that they were getting better over time. If they had, they wouldn’t be facing the uncomfortable question of why they gave a free pass to a district that now seems to be moving backward.

Apparently, generative AI has made the traditional academic essay obsolete—and so, for our own good and the good of our students, it is time we scrap them. Over at The Atlantic, English teacher Daniel Herman calls the essay “no longer useful.” And some professors lament that AI marks “the end of writing assignments“ as we know them. Bollocks.

The general thrust of this argument is old and dusty. In 1899, facing the Industrial Revolution, progressive theorist John Dewey advanced a version of it: “that this revolution should not affect education in some other than a formal and superficial fashion is inconceivable.” In both Herman’s and Dewey’s minds, since technology has changed, education must change.

While plausible on its face, this argument is ultimately flawed. Traditions such as family dinners are all the more important with the advent of modern technology. Handwashing and exercise remain the best prophylactics against disease, even with modern medical therapies. The traditional academic essay, too, still has much to offer students, much that goes far beyond the simple act of writing it.

In all my years teaching, never did I consider an academic essay an end in itself. Whereas Herman suggests that students only write an essay in school so they can write research papers in college, I openly confessed to my students that they’d never need to write a five-paragraph essay in their professional lives. Rather, an essay was a means to different ends.

An essay teaches control of language. It teaches how to organize thoughts and structure them such that a reader can easily follow them. It teaches how to state an argument clearly upfront, hook a reader’s interest, and conclude in a concise, powerful way. It teaches students how to weave together data and compelling anecdotes such that a piece of writing is both accurate and interesting. It’s a place to practice rhetorical strategies like repetition or analogy. Any professional writing, from a workplace email to a newspaper op-ed to a careful blog post, benefits from these skills.

But having rejected the essay, Herman suggests that we focus on what makes teaching “meaningful and potentially life-changing: the communal experience of being in a classroom.” His vision for the English classroom resembles a glorified book club. Or maybe bull session. There are two flaws with this ideal, one practical and the other theoretical.

Practically, sitting around discussing whether students like a book requires little attention to detail or real analysis. Herman’s focus on extemporaneous writing like journal entries and short reflections deprives students of the benefits of formal writing. Revising, extended consideration of one idea, clarifying thoughts after feedback—these are the forces that hone student thinking. Shooting the breeze in a circle discussion or jotting down an off-the-cuff reaction simply doesn’t push thinking in the same way.

That’s not to say that classroom discussion and extemporaneous writing have no place. Socratic discussions and oral examinations have a storied history, and brief, initial reactions help a student process their thoughts before coalescing them into a more structured format. I ended every unit by reorganizing my students’ desks into a circle and discussing the themes of our recently finished novel in an open-ended discussion format. Students learn through these classroom activities, but the demands of an essay teach distinct lessons, too.

Herman provides an example of one student who connected the exploitations of whaling in Moby-Dick to the shortcomings of modern capitalism. There’s a vast amount of writing skill and factual knowledge a student must master to write that essay well. One of my own students analyzed Romeo and Juliet through the lens of different Greek words for love—agape, storge, philia, and more. No mere discussion can foster that depth of analysis.

The theoretical flaw is in Herman’s assumptions that the communal experience alone is meaningful or life-changing. Quite the contrary: Teaching students formal academic knowledge such as the mechanics of writing—emphasizing evidence and formal structures over passing impressions and reactions—is what teachers uniquely can offer. Students can sit around and chat with their friends. Can they teach each other how to use an appositive phrase or fronted adverbials to trim turgid prose?

We still revere the power of constraint in the realm of music. It’s not a student left to plunk out random notes that achieves musical freedom. It’s not a child who listens to and discusses music all day who masters the craft. Rather, it’s the one who spends hours practicing scales or memorizing songs who is liberated in the long run to play Chopin’s “Nocturnes” or whatever else fits their fancy.

Children will become engaged, thoughtful writers only once they’ve mastered language. That is meaningful and life changing.

ChatGPT can do many things, but it can’t teach us how to think. Until AI masters that skill, traditional assignments—from practicing math facts to writing an essay—will remain essential elements of any productive classroom.

Tensions between parents and educators are at an all-time high. Differences in opinion about education are not new, and they certainly do not have to lead to a corrosion of trust. Yet that is exactly what has happened, and both groups shoulder blame—as does the media.

It’s undeniable that parent conduct has been out of control since the pandemic. Ask a teacher or principal in any type of school district you can think of, and they will likely tell you that, during their entire time in education, the last few years have been the worst in dealing with parents. In one study, 29 percent of teachers and 42 percent of administrators reported at least one “incident of harassment or threat of violence” from parents. Family members have come to schools armed to settle disputes and threaten staff in the School District of Philadelphia, for example. Parents were arrested at a South Carolina school after fighting in the lobby. School board meetings in California have seen violence break out. Youth sporting events in Indiana have led to referees being attacked on the court. A sixty-year-old grandparent died shortly after a parent brawl in Vermont.

The education system is at fault, too. Taken as an institution that should include everyone from teachers to school board members to politicians, it has contributed to the parents’ growing distrust. Concerned parents were labeled “domestic terrorists.” Politicians campaigned on messages like, “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach,” with teachers union leaders echoing the sentiment. Educators have posted performative videos, engaged in questionable classroom practices, and taken sides in the culture wars, much of which parents saw firsthand during virtual instruction. School leaders and school boards consistently implemented discreditable policies over the course of the pandemic that deteriorated parental confidence. Such actions warrant a cynical response from parents who deserve much better treatment and performance from educators.

And journalism has fanned these flames. No matter what side of the debate you’re on, there have been countless examples of the media exaggerating or straight-up lying. Imagine, as a parent, reading headlines that your child’s school in Houston is “turning libraries into discipline centers,” a claim refuted by Dale Chu’s on-the-ground reporting. Or that your school district in Tennessee is “banning Maus”—when in reality they’re just engaging in the routine practice of changing curricula. Misleading and dishonest reporting has led to an uninformed and increasingly angered public over largely false narratives. Parent and school relations cannot improve if we have a media that continues to prioritize divisive cultural war issues over honest education stories that actually matter.

To restore relations and build back trust between parents and schools, we don’t need to “reimagine education” as U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona puts it. We need a reset. And there’s at least four strategies for schools and parents to accomplish this.

First, schools should make expectations clear to parents by establishing a code of conduct like the almost fifty schools in the UK that have demanded parents agree to follow rules concerning social media behavior and even dress code when they pick their students up. They can also make parent obligations such as timely communication and attending meetings mandatory much like Success Academy in New York City does.

Second, school leaders must gain the courage to justly enforce consequences for parents failing to meet these expectations. This is not an easy task for traditional public schools, as enforcing a dress code for parents can cause national outrage or prohibiting parents from school board meetings may result in legal action. Yet, there are ways—grounded in common-sense, fairness, and the law—for leaders to overcome such constraints. A superintendent in Pennsylvania demanded more of parents through a persuasive plea that appealed to the common senses of parents concerned with school safety. New Mexico’s state athletics association passed a harsh but fair rule banning an entire team’s fan base from spectating for the season if a parent commits two acts of unsportsmanlike conduct. And lastly, if warranted and through due process, courts have ruled in favor of schools exercising accountability measures, such as banning parents from school property.

Third, school leaders and staff have to accept warranted criticism from parents and be willing to address justifiable parent concerns. For example, the aforementioned Success Academy doesn’t just hold high expectations for parents, they also hold the same demands of themselves. In their policies, they detail what parents should expect of them, such as agreeing to respond to parents within twenty-four hours, providing countless opportunities for parents to engage with staff, and ensuring parents are integrated in improvement plans based on their feedback.

Fourth, schools must be transparent with moms and dads about curriculum and day-to-day operations in classrooms. While bills in state legislatures and Congress demanding transparency haven’t had much success, schools should be willing to post their curricula, materials, and instructional methods online, and ensure teachers follow it. Parents also can’t be left in the dark regarding what’s going on in the school. Proposals for cameras live streaming classrooms may be asking too much, but schools should be required to share information to parents involving their child, whether it’s about serious incidents, gender-identity changes, or self-harm. And consider encouraging parents to actively volunteer in the building, such as the fathers at a Partnership School in Cleveland who provide mentoring and support to students throughout the school day.

This road to recovery is a two-way street. Marriage counseling doesn’t really work if just one spouse participates. And like marriage, a divorce or unhealthy relationship will most likely cause worse outcomes for the kids. The faster parents and educators realize that they both need to work on themselves, the stronger their thirteen-year commitment to each other will grow, and the better off America’s children will be.

A new study from a pair of Penn State University researchers finds that passing the U.S. Citizenship Test as a high school graduation requirement does nothing to improve youth voter turnout. Within the last decade, more than a third of U.S. states have adopted and implemented a version of the “Civics Education Initiative“ (CEI), but according to study co-author Jill Jung, a graduate student in education policy studies, “when it comes to improving voting among youth, mandating civics tests that focus on assessing political knowledge might be a wasted effort.” The study by Jung and Maithreyi Gopalan appears in Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association.

The U.S. Citizenship Test has been in place since 1986. It consists of a list of 100 questions about American history, our system of government, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens. Immigration officials administer the test orally, asking would-be citizens seeking naturalization ten of the 100 questions; they must answer at least six correctly to pass. The questions aren’t particularly difficult. They consist of things like naming any one of the three branches of government, how many U.S. senators there are, and naming a right or freedom guaranteed by the First Amendment. Rock-bottom, basic stuff.

I was an early proponent of making the citizenship test a graduation requirement. About a decade ago, I helped launch a short-lived civic education initiative based at Democracy Prep Public Schools, a Harlem-based charter school network dedicated to civic education and engagement. Passing the citizenship test was a graduation requirement for DPPS students—and not just six out of 10, but all 100 questions with a passing score of 83 correct. We launched a pledge effort aimed at educators, politicians, and policymakers called “Challenge 2026” that would make passing the citizenship test a national high school graduation requirement by the nation’s 250th birthday. The Arizona-based Joe Foss Institute had far more success gaining traction for the issue and, frankly, a better strategy: getting state legislatures to adopt it as a high school graduation requirement, which eighteen states have done so far.

I take no issue with the finding that those states have seen no increase in youth voting, but the impetus was never to improve voter participation. It was to correct a profound national embarrassment: More than 96 percent of immigrants seeking naturalization pass the test—a rate that Americans at-large are nowhere near matching. Only 13 percent, in one survey, knew when the U.S. Constitution was ratified, for example. Most couldn’t say which countries the U.S. fought in World War II. Only one in four could even say why American colonists fought a war against Great Britain. Unsurprisingly, older Americans have the easiest time of it, with 74 percent answering at least six in ten questions correctly. Among those under the age of forty-five, only one in five pass, which says a lot about the debased standards of common knowledge expected of students in U.S. schools, whose founding purpose was to prepare ordinary people for self-government.

It is hard to overstate what a low bar the citizenship test represents. At one conference I attended, a teacher at a Core Knowledge charter school, a naturalized immigrant herself, pointed out that seventy-five of the 100 questions on the U.S. Citizenship Test were covered in the Core Knowledge Sequence by the end fourth grade. Moreover, there is the simple and obvious double standard: Why hold immigrants accountable for knowing a few basic facts about our history and system of government, but not students in our own schools? Still, there was an awful lot of tut-tutting from “serious people” in civic education about making the citizenship test a graduation requirement. It’s trivial pursuit! It’s mindless memorization! It takes time and energy away from “serious pursuits” in civics, such as authentic engagement in government, student activism, and grappling with “real issues.”

Never mind that lacking basic knowledge makes it hard to understand how or why to fight for change, our obligations and rights as citizens, what constitutes appropriate democratic conduct, or why a certain amount of frustration is a healthy feature of life in our system. The unexpected resistance to this modest minimum eventually wore me down until I had to agree that the critics were right and I was wrong. I no longer think it’s a good idea for the U.S. Citizenship Test to be a high school graduation requirement.

It should be an elementary school graduation requirement.

Editor’s note: This was first published by the American Enterprise Institute.