- Young men continue to benefit from affirmative action as the number of women at most colleges continues to surge. —New York Times

- Public trust in universities has plummeted in the last decade, and enrollment numbers have followed; rising costs and wokeness are to blame. —Paul Tough

- Mississippi didn’t fudge its reading gains with student retention, but achieved real, lasting academic improvements through smart policy. —Washington Post

- Many states and schools are moving away from credit hours and towards a competency-based system of graduation requirements. —The 74

During the 2015–16 school year, Ohio launched a revamped dual-enrollment program called College Credit Plus (CCP). This state-run, state-funded program offers academically eligible students in grades 7–12 the opportunity to earn postsecondary credit by taking college courses for free before graduating from high school. State law requires all public schools and public colleges and universities to participate, but dozens of private schools and private higher education institutions also choose to do so.

Given the state’s significant investment—just over $55 million was paid to colleges and universities through CCP in 2022—as well as the program’s myriad potential benefits for students and families, it’s imperative that state leaders keep a close eye on it. In 2021, the Ohio Auditor of State conducted a performance audit that offered an in-depth look at the program.

The good news is that overall participation, student impacts, and tuition savings are positive. The bad news is that traditionally underserved groups are missing out on CCP’s benefits for a variety of reasons, and one of them seems to be a lack of state oversight. The audit found that there were “significant levels of non-compliance with program requirements among school districts.” For instance, surveys revealed that nearly half of districts—43 percent—didn’t start communicating with students about CCP until high school, even though state law requires them to begin in sixth grade. Similar non-compliance issues cropped up with digital information access. Districts are required by law to promote CCP on their website, but 37 percent reported that they didn’t. In both cases, districts that followed the law—they began their communication efforts prior to high school, and promoted the program on their website—reported a higher number of CCP hours per student.

The audit also suggested that by modifying forms and muddying informational waters, some districts were discouraging students from participating (perhaps because CCP courses are funded via a deduction to districts’ state aid). The Ohio Department of Higher Education provides schools with standard templates for program applications and forms, but the audit notes that it’s “common” for districts to edit these templates before using them. The department’s annual notice form, for example, is intended to provide families with concise and accurate information about CCP. But approximately 80 percent of the documents reviewed by the audit team were different from the template, and more than half were missing at least one element. Audit findings also indicated that some districts added “guidance” regarding costs to their intent to participate forms. Because they “did not clearly indicate” that the default participation option allows students to complete courses for free, families might have assumed there was a substantial cost associated with the program and avoided signing up.

You might be wondering how a state-run program that’s well past its infancy could allow so many districts to break or bend the law to the detriment of students. The audit offers an answer: Because there’s no “formal compliance or oversight function for CCP” established in law, the state education agencies that oversee it “are not required to, and have chosen not to, take the initiative necessary to follow through with compliance-related activities.” In other words, even though the law says that districts have to do these things, no one is making sure they actually do. As a result, students and families all over the state are losing out on the potential benefits of dual enrollment.

Fortunately, lawmakers have been paying attention. Senate Bill 104, which was introduced this spring, would address many of the problems identified by the audit. The most significant provision mandates that the leaders of the state agencies responsible for running the program—the Department of Education and Workforce and the Department of Higher Education—shall “monitor and enforce compliance” with state requirements for public and participating nonpublic secondary schools, state colleges and universities, and participating private institutions of higher education. This explicit mandate would add much-needed oversight to the program, and would eliminate the existing loophole that allows districts and schools to ignore state rules and laws.

Should it become law, the bill would also do the following:

- The Department of Education and Workforce would be responsible for including on state report cards data indicating whether a school provides information to students and families about CCP and promotes the program as required by law. This data wouldn’t be a rated component, and would be identified by a simple “yes” or “no.”

- Public and participating nonpublic schools would be required to use forms developed by the state. Schools would be prohibited from modifying any form without approval.

- Public and participating private colleges would be required to provide participants with an orientation that meets guidelines issued by the overseeing agencies. This is likely an effort to smooth students’ transition between high school and college courses.

- Under current law, students or their parents must notify their secondary school by April 1 that they intend to participate in CCP the following school year. SB 104 would adjust this timeline and allow for notification prior to the next semester rather than the next school year. There would still be a notification deadline chosen by the chancellor of higher education, but allowing students to opt-in every semester rather than once a year should make CCP more easily accessible.

- The chancellor would be required to establish an alternative credentialing process to certify as CCP instructors those who have relevant teaching experience without requiring them to complete additional graduate-level coursework. This follows in the footsteps of other recent state policy changes seeking to eliminate burdensome requirements that keep qualified teachers out of classrooms.

- Current law requires secondary schools to treat CCP courses as equivalent to AP, IB, and honors courses when awarding grades and determining class standing. That means if it’s school policy to weight AP, IB, or honors courses, then CCP courses must be weighted, as well. SB 104 clarifies that this requirement pertains to all CCP courses.

- Under current policy, the cost of college textbooks is deducted from district funding when a student participates in CCP. These costs have long been the subject of ire from districts, which complain that prices are too high and textbooks often go unused. SB 104 would address this issue by requiring participating colleges and universities to “endeavor to use open-source materials, in lieu of purchase-only textbooks” in CCP courses as much as possible. If a purchase-only textbook is used when open-source materials are available, the higher education institution would be required to cover the textbook cost. However, if there are no open-source materials available, the cost of the textbook would be split fifty-fifty between the institution and the secondary school.

All things considered, SB 104 is a smart piece of legislation that directly addresses many of the issues identified by the CCP audit. These changes would strengthen the program, and would help ensure that every academically-prepared student has access to dual-enrollment courses. Here’s hoping lawmakers take up and pass SB 104 during the upcoming legislative session.

- Looks like someone’s been listening to Fordham’s Aaron Churchill, who has been advocating for including party labels for candidates on local school board ballots for many years, with lots of great analysis backing it up. Those opposing the idea choose another tack for their arguments: “This [party-less ballots] has been working since I don’t know when, maybe since the beginning of the state of Ohio. Why change it now?” I mean, who can argue with logic like that? (Gongwer Ohio, 9/11/23)

- Same energy in yesterday’s House Primary and Secondary Education Committee meeting, where the same proposal was debated with regard to the state board of education, including the prospect of party primaries for candidates for election to that august body. (Gongwer Ohio, 9/12/23)

- Teachers are still on strike and students are still experiencing remote learning in Youngstown today. But it seems like some movement occurred yesterday after a meeting of the elected school board produced a counterproposal the superintendent hopes is “digestible” by the rank and file. Of note: The contentious ADC language appears to have been stricken from the contract, but at something of a price. I suppose we’ll find out soon whether the proposal stayed down or came back up. Ew. Excuse me for a minute… (WFMJ-TV, Youngstown, 9/13/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Editor’s note: This is part two of a three-part series. Part one examined possible causes. This was first published on the author’s Substack, The Education Daly.

Last week, we ran through the many possible explanations for the rise in absenteeism. They come in all shapes and sizes, some more plausible than others.

This time, I’d like to unpack how this issue plays out in cities and suburbs. It’s no secret that the pandemic has caused the biggest expansion of academic inequity in generations. One might presume the same thing happened with absenteeism—that is, the effects were felt most by the lower income families that always seem to receive the short end of public services. But what stands out most is how kids are missing school everywhere.

Let's start with Oakland

You probably know already that chronic absenteeism is epidemic in our big cities.

The numbers are depressing and have been widely reported. New York City’s chronic absenteeism rate hit 41 percent in 2021–22. Los Angeles was 45 percent. In Detroit—and it’s hard to believe this is not a typo, I know—it was 77 percent. Google any major district and you’ll find a similar headline.

I am particularly interested in the Oakland Unified School District, partly because it has a comprehensive and highly transparent dashboard detailing attendance patterns for more than a decade. (Good job, OUSD!)

I organized the data from 2012–23 below:

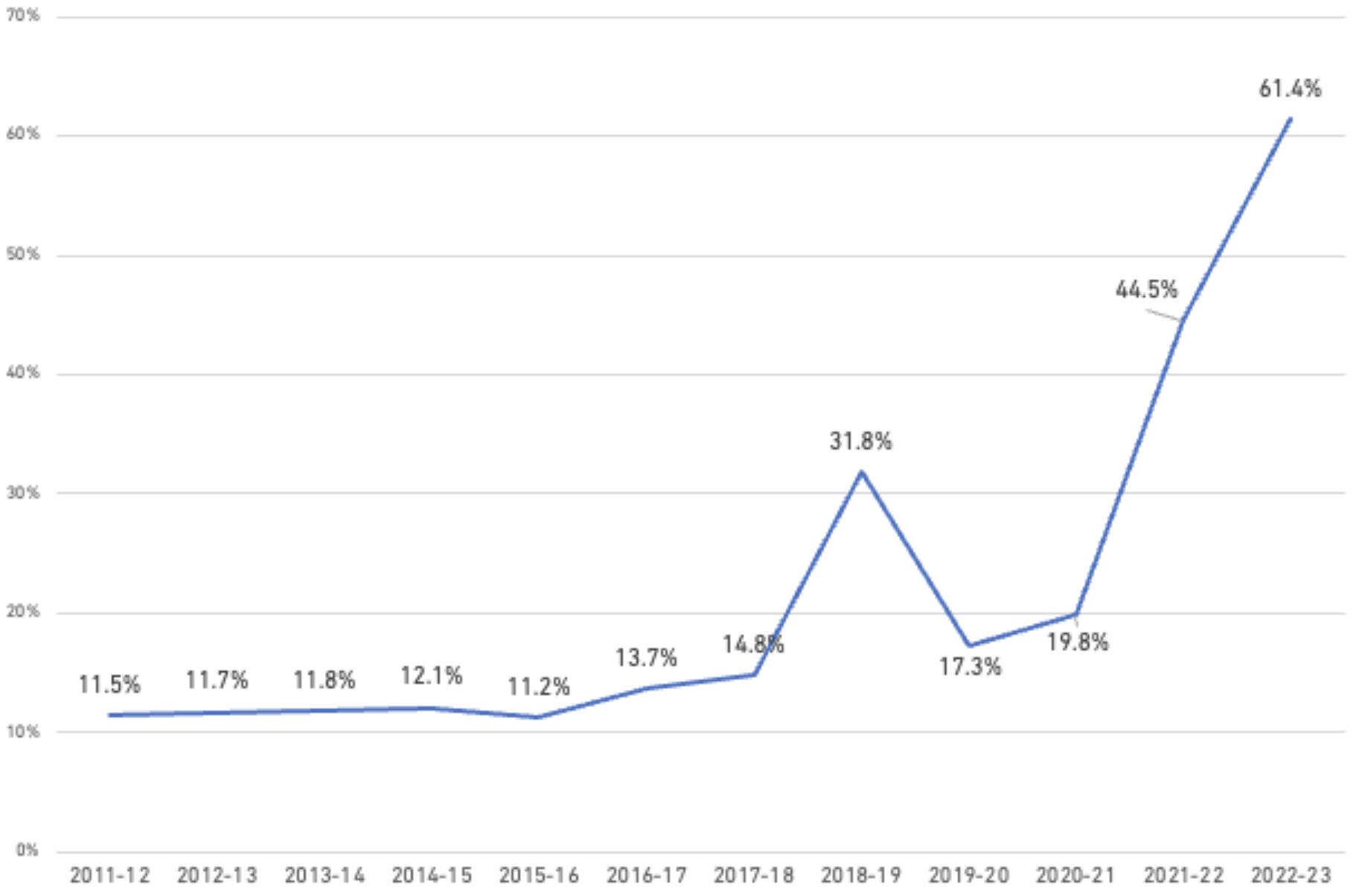

Figure 1. Percentage of OUSD students chronically absent by year, 2012–2023

Source: Oakland Unified School District, Dashboards, Attendance Group Snapshot, retrieved from https://dashboards.ousd.org/views/ChronicAbsence_0/Comparison?:embed=y&:display_count=no&:render=false#40

Overall, 61 percent of Oakland kids were chronically absent in the most recent school year, 2022–23. While rates were concerning across the board, figures were higher for Black and Latino students (70.5 and 67.2 percent, respectively) than for White and Asian students (47.8 and 35.6 percent). This is consistent with trends elsewhere. Students of color often face heightened barriers to regular attendance.

The real shocker is how much chronic absenteeism has grown for all students in the past decade. In 2011–12, the first year tracked on OUSD’s dashboard, only 11.5 percent of all enrollees missed 10 percent or more of school days. As you can see from the graph, levels remained pretty steady for a number of years. But by 2017–18, they began to climb noticeably. There was a major surge in 2018–19—before the pandemic—to almost 32 percent.

While absenteeism appeared to drop in 2019–20, that was the year the pandemic arrived. Schools were entirely closed from March onward. Attendance tracking was understandably wonky. (Read: generous.) As schools reopened for in-person learning full time, absenteeism went through the roof.

The new normal is more missed school for every subgroup. For example, White students in Oakland today are chronically absent at a much higher rate than was the case for Black students eleven years ago.

Same district. Minor demographic changes over a decade but nothing revolutionary. How did Oakland go from approximately 12 percent chronic absenteeism to 61 percent? And how on earth will efforts to address lost learning such as increased mental health support and high dosage tutoring make any difference when a majority of the district’s students miss an average of one day of school every two week—at a minimum.

I wonder whether Oakland will ever regain its levels of school attendance from a decade ago. It’s hard to be optimistic.

Just as an example, the district cut the positions of five attendance officers prior to the 2022–23 school year. What? Then it weathered a teacher strike, and absenteeism got worse.

What about the suburbs?

It’s true that chronic absenteeism is more acute in low-income communities where evictions, homelessness, and isolation from health care and social services are widespread. That’s a story we know well. Always been that way. But if economic inequity is the sole driver of today’s absence epidemic, someone needs to explain what’s happening on Chicago’s North Shore.

New Trier Township High School serves some of the wealthiest suburban communities in the country, including Wilmette, Kenilworth, Winnetka, and Glencoe. Nearly 90 percent of the study body is White or Asian. Students and families have access to incredible supports through their own resources. On top of that, the school itself is absurdly well-funded. It’s difficult to believe that a significant number of New Trier students are absent due to traditional hardships like not having transportation.

But nonetheless, they are absent in huge numbers. As reported in the Chicago Tribune last spring, 25 percent of the student body was chronically absent for the 2022–23 school year as of February 10. Most intriguingly, “the percentage of chronically absent students rose by class with just over 14 percent of freshmen, 21.4 percent for sophomores, 27.8 percent for juniors, and almost 38 percent for seniors.”

You read that correctly: Almost 40 percent of seniors at one of the nation’s most privileged public high schools had problematic attendance. A swarm of Ferris Buellers, attendance-wise. One can’t help but sympathize with beleaguered Superintendent Paul Sally, who told the Tribune “We’ve been looking at this and struggling with this in a lot of ways.”

The freshman are showing up. The seniors are not. The skew of absence patterns toward older groups is consistent with a theory that absenteeism is in significant part a social contagion exacerbated by diminishing accountability as students approach graduation with the grades and credits they need for college already secured. Kids aren’t tolerating any more high school than is absolutely necessary.

New Trier seems to see it this way. For the new school year, the school formed a committee that recommended substantially more stringent policies for absences, including a ban on participating in extracurriculars on the same day a student misses school. The board and administration are not treating absenteeism as a problem that will fix itself.

Time will tell if New Trier gets its students back in school. But credit them for acknowledging the problem publicly, defining its dimensions with transparent information to the public, and laying out specific interventions.

Districts across the country are in the same boat, searching for the best solutions.

So what did we learn today?

1. For a district like Oakland, this is not a matter of a post-pandemic rough spot. Absenteeism was already rising before Covid. There’s a deeper thing going on. And the bottom line is: More than five times as many Oakland kids are chronically absent today compared to a decade ago.

2. Nobody should be pointing fingers at low-income parents as the root problem, as if they are uniquely unwilling or unable to get their kids to school. Plenty of students from our nation’s wealthiest families are chronically absent, too. For every demographic group, numbers have gone up. Just like with the pandemic, we’re all in this together—like it or not.

3. Districts have started to realize that the spike in absenteeism is not going to dissipate magically on its own. They are becoming more assertive with remedies.

Next week in our third (and final) installment on this issue, we will consider those remedies more carefully, parsing arguments for relying more on carrots or sticks, so to speak. I’ll offer some specific recommendations of my own.

You may already know that back-to-school time means that nominations and applications are being accepted to join the National Assessment Governing Board (NAGB) a year from now. Here’s why you—and topnotch colleagues and friends—should take this seriously.

NAGB is, quite simply, the most important K–12 policy-making body in America, short of Congress itself. (And unlike Congress of late, it actually makes decisions—almost always collaborative, non-partisan decisions—and gets stuff done.)

No disrespect to the New York Board of Regents, the Tennessee State Board of Education, or a hundred other essential policy bodies at the state level. Here I’m talking about the national level. That’s where the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) matters and where its governing board matters.

NAEP measures and reports what U.S. students know and can do across almost every K–12 subject. It does that in grades four, eight, and twelve, and in the core subjects of math and reading, it reports those results not just for the country as a whole, but also for individual states and a growing number of cities. Not only does it tell us whether our kids are gaining or losing ground, its “basic,” “proficient,” and “advanced” levels are benchmarks against which states and districts (and federal officials) gauge the adequacy and rigor of their own standards and tests. They’re the closest thing the U.S. has to national standards for K–12 education.

But who makes all those decisions? They don’t come from ChatGPT. They don’t come from the U.S. Department of Education bureaucracy (though NCES has essential roles). They don’t come down from some higher power, nor from Congress, the Secretary of Education, or the White House.

They come from NAGB. NAGB decides what will be assessed, how often, how it will be reported, what questions will be on the tests, how they’ll be administered, how to accommodate special-needs students, and maybe most important, where to set those cut-points on the scale that denote proficiency, etc. NAGB is who decides “how good is good enough” in American K–12 education.

What’s more, NAGB has the authority to make such decisions. Unlike the Education Department’s myriad “advisory” and “operational” committees, NAGB is a true governing board. Its statutory powers are extensive, exhaustive even, and (says the law), “In the exercise of its responsibilities, the Assessment Board shall be independent of the Secretary and the other offices and officers of the Department.”

That’s why I say it’s the most important K–12 policy-making body in America.

How this came to be in a multi-chapter story that began a half century ago and took its more-or-less present form in a 1988 statute combined with 2002’s No Child Left Behind act. (You can read all about it in Assessing the Nation’s Report Card: Challenges and Choice for NAEP and a shorter account of the standards-setting saga in “It Felt Like Guerilla Warfare.”)

I took part in some of that, and Secretary Bill Bennett asked me to help him appoint the first round of NAGB members—and then to chair the group myself, which I did for a couple of years at the start (1988–1990). It was a formative moment for the board and for NAEP, including the launch of state-level reporting (optional for states pre-NCLB) and the arduous birth of those “achievement level” lines across NAEP’s age-old “vertical scores.”

It was also an exhilarating time as two dozen individuals came together from all parts of the land, from every sort of political orientation and professional background—practicing educators, elected officials, state and local leaders, members of the “general public”—and forged a coherent, mutually respectful body that almost transcended constituency interests and personal preference in pursuit of a common good. We argued, we debated, we sometimes sparred with NCES management (for they actually operate NAEP), we summoned all manner of experts and advisors, we dug deep, we relied on a small but highly motivated staff—and ultimately, we nearly always found ways to come together with mostly-unanimous decisions about this very important testing program that was now our responsibility.

This work was satisfying, too. As I wrote in my book about NAEP, “Many NAGB alums keep in touch with teach other and with NAEP goings-on. Many look back on their board terms as challenging but gratifying public service that they’re exceptionally proud of. Many also recall their NAGB experience as valuable professional development for themselves and their careers.”

With rare exceptions, NAGB has continued in that mode for more than three decades. But to make that happen, it needs smart, committed, hard-working members who are game to roll up their sleeves, work with their colleagues, and commit a lot of time and effort to a venture for which the main reward is the sense of having done the job as well as it can be done. (Expenses get covered and there’s a very modest honorarium that doesn’t begin to compensate for one’s labor.)

The Secretary of Education appoints NAGB members, but they’re nearly always chosen from among those the board itself nominates. So the first step in joining NAGB is to apply—or get nominated—to the board. That window is open now and will stay open through October. You can read all the particulars here.

Six slots need to be filled by September 2024. They are

- General Public Representative - Parent Leader

- Local School Board Member

- Non-Public School Administrator

- State Legislator - Democrat

- State Legislator - Republican

- Testing and Measurement Expert

If you or someone you know might qualify in one of those roles—and you surely know people who do—please consider applying (or nominating). Yes, it’s hard work. But, especially in our post-pandemic achievement slump, the country has never relied on NAEP as much as it does today.

Besides, as I said at the start, we’re not making small talk. We’re talking about the most important K–12 policy-making body in America. Become part of it.

It’s September and that means fall elections are coming soon. Not that election—the presidential is still more than twelve months away—but local school board races are right around the corner. These are important contests, as school boards play a critical leadership role in public education, but if history is any indication, turnout will be small.

First, why are school boards so important? These bodies establish the academic policies and priorities that drive district actions. They adopt curricula and instructional materials and institute policies that heavily impact the daily work of educators. They make budgetary choices about which programs are funded or cut, and with district administrators, they negotiate sprawling, multi-million-dollar employment contracts with the unions. They also make decisions about putting local tax requests on the ballot, which can directly impact citizens’ finances. Last but not least, their attitudes and values can influence the way districts respond to the sensitive, sometimes charged, issues that arise in education.

Despite the significant powers and responsibilities of school boards, appallingly few citizens vote in these elections. One key reason for the low turnout is their “off-cycle” timing. School board races—along with other municipal elections, per state law—are held in odd-numbered years when national and statewide elections are off the ballot. That needs to change, and here’s why.

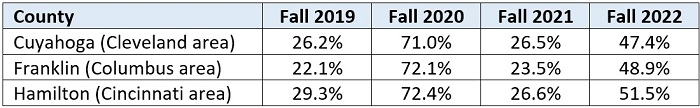

Table 1 shows the sharp differences in turnout for the most recent fall elections in Ohio’s three most populous counties. In Cuyahoga County, an abysmal 27 percent of registered voters participated in the fall 2021 off-cycle elections when school board races were contested. Meanwhile, 71 percent of the county’s voters went to the polls in fall 2020—a presidential election—and 47 percent voted in fall 2022 (mid-terms). The turnout patterns are very similar in Franklin and Hamilton counties.

Table 1: Voter turnout rates for off-cycle (2019 and 2021) and on-cycle (2020 and 2022) elections

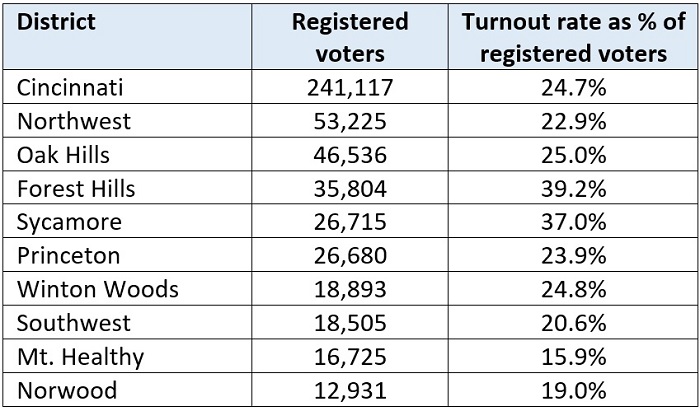

Given these countywide numbers, turnout for school board races at an individual district level are predictably low. Just a quarter of Cincinnati voters went to the polls to choose district board members in the 2021 cycle. Less than 20 percent of voters in Mt. Healthy and Norwood turned out.

Table 2: Voter turnout rates in ten largest Hamilton County districts by voter registration, fall 2021

Low turnout shouldn’t be laid at the feet of citizens, many of whom are busy with occupational and family responsibilities. It’s possible that employers may not give employees time off to participate in off-cycle elections, as they do for national races. And some voters may not have the bandwidth to plug into board races that are held at a time when politics and campaigning is usually more subdued. Writing recently in The Atlantic, Jerusalem Demsas opines, “We have too many elections, for too many offices, on too many days. We have turned the role of citizen into a full-time, unpaid job.... One of the most pernicious ways politicians overburden voters is by holding off-cycle elections.”

Scholars also contend that sleepy school board races give disproportionate influence to certain segments of the electorate—most notably, district employees. This voting bloc has an obvious self-interest in school board elections, no matter when they are held, as sympathetic boards can ease working conditions, provide more generous leave, and increase pay, among other things. Moreover, because most district employees are unionized, they can organize both themselves and their allies to vote as a unified bloc for a “slate” of union-endorsed candidates. In most districts, no other group is likely to have the same organizational capacity to get candidates elected, especially during an oddly-timed school board race.[1]

Commenting on the undue sway of employee unions in low-turnout races, Stanford University’s Terry Moe writes, “In school-board elections, the incentives of the teacher unions are strong and clear. If they can wield clout at the polls, they can determine who sits on local school boards—and in so doing, they can literally choose the very ‘management’ they will be bargaining with.” A study by Sarah Anzia of the University of California finds that teachers do in fact benefit from this cozy arrangement. They receive higher pay when their districts hold off-cycle races, with senior teachers accruing the greatest benefit.

Ohio lawmakers should put an end to these poorly attended and skewed elections, and instead require school board races to appear on the ballot in even-numbered years. This “on-cycle” scheduling would substantially increase voter turnout, as Ohioans could select their local board members at the same time they cast their vote for president, governor, and other national and statewide leaders. This scheduling change would ensure that parents are given a stronger say in their districts’ board membership. It would also promote a more diverse electorate that looks more like the students attending district schools, as less advantaged groups tend to vote at higher rates in general elections.

Moving school board elections on-cycle not only makes common sense, but should also find bipartisan support. Progressive groups such as the League of Women Voters and the ACLU have long supported voting policies that encourage more public participation. On-cycle board elections certainly check that box. Conservatives, too, have lent support for on-cycle elections, arguing that it would increase public accountability and enhance the voice of parents. Former Ohio Secretary of State Ken Blackwell (R) recently wrote in the Cincinnati Enquirer: “If we can increase voter turnout in school board elections [through on-cycle voting] and get more parents to vote, we are likely to see a school board with policies more representative of the entire constituency rather than one small group.”

For democracy to work, citizens should be encouraged to participate in the electoral process. Unfortunately, off-cycle timing suppresses widespread public participation in school board elections and gives special interests undue power to “capture” the board. To give all citizens a more equal voice in district leadership, it’s time for Ohio lawmakers to move school board elections on-cycle.

Join us to discuss Fordham’s recently published report Excellence Gaps by Race and Socioeconomic Status.

Some Ohio public schools may be headed for a world of hurt. They’ve been on a spending binge due to the massive $6.7 billion infusion of federal pandemic relief funds, and they’re facing a potentially devastating fiscal cliff when those funds run out during the 2024–25 school year.[1] If school leaders don’t plan wisely for the phase-out of these emergency dollars, student progress could suffer in the years ahead. And because the funds were distributed in a manner that awards more money to low-wealth districts, disadvantaged students are at greatest risk.

The purpose of the unprecedented federal aid was to help schools reopen safely and remediate student learning loss. But the dilemma facing many districts today is that they’ve used the temporary funds to take on long-term financial obligations, such as hiring new staff and raising educator salaries, that will be difficult to scale back when these dollars dry up. Indeed, some districts have taken on additional long-term spending when they should have been cutting expenses to address both long-term and pandemic-related enrollment declines.

The influx of federal funds has also significantly distorted district budgets, in that some districts have been so awash in money that they have little sense for the essential costs of running their schools and what they can afford. For example, over the last three years, Columbus City Schools has been awarded nearly $475 million dollars in federal Covid money, which is about half of the district’s pre-pandemic annual expenditures.[2] Even if Columbus City Schools has somehow maintained perspective on how to run a district within its means, getting back to a right-sized budget could be a shock to the system. The district’s May 2023 budget forecast mentions the impending “fiscal cliff” as a “significant risk,” specifically noting concerns about how to pay for 430 new full-time staff members hired using pandemic relief funds. This figure likely understates the excess staffing, as enrollment declines warranted cuts in district staff.

By now, all Ohio districts should see the fiscal cliff coming. The federal government made clear that these were emergency funds, not a permanent allocation, and budgeting experts and government officials have regularly warned districts about the approaching cliff. Ohio is also one of the few states that requires school districts to conduct and report multi-year financial forecasts, which forces districts to grapple with projected declines in future revenue. Sensing the coming storm, some districts are already cutting spending or putting tax levies on the ballot, hoping local taxpayers will bail them out by paying for some of their new, long-term obligations, such as increases in staffing and salaries. The Ohio General Assembly’s financial generosity in recent years will cushion some of the blow, as well.

Even if districts see the cliff coming, however, my research on the aftermath of the Great Recession—when federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds eventually expired—suggests that the negative impact on student achievement will be significant if they don’t plan wisely.[3] Districts can make significant errors when forecasting future funding streams, even when they generate forecasts at the end of one school year about how much revenue they will have in the next year, just a few months later. That’s how uncertain school financial management can be. A surprise revenue shortfall due to an overly optimistic forecast requires districts that lack cash reserves to make sudden budget cuts that can disrupt district operations and student learning. Pandemic aid has significantly distorted district finances and make costly forecasting errors more likely after federal money runs out beginning in 2025.

The impact of such forecasting errors can be significant. My coauthor, Travis St. Clair, and I found that after federal stimulus funds ran out in 2012, every percentage point increase in unexpected revenue shortfalls led to a decline in student achievement of 0.02 standard deviations (about eight days’ worth of learning) among Ohio public-school students. For the average district that had an unexpected revenue shortfall (approximately 15 percent of Ohio districts in a given year), students lost about three weeks’ worth of learning relative to students in districts that spent a comparable amount per pupil but that did not make such a forecasting error. Predictably, these shortfalls corresponded to sudden cuts in staff and efforts to raise revenue with new tax levies on district residents.

The harmful disruptions documented in our study were not due to lower spending levels or the shock of the Great Recession itself. The negative impacts all occurred after federal relief funding expired after 2012—three years after the recession ended—because districts failed to accurately forecast changes in revenue. Students experienced achievement declines because districts unexpectedly had to cut spending all at once, as opposed to gradually reducing spending in anticipation of lower revenue in the future.

As one would expect, the large negative impact of budget forecasting error was particularly acute among districts with relatively low cash balances. Districts with cash balances below the median of 22 percent of annual operating expenditures—just over the sixty days of reserves at the top end of recommendations from the Ohio Department of Education and the Government Finance Officers Association—experienced large student achievement declines. Further analyses (which we did not publish) suggested that these districts continued to cut expenses in subsequent years—even in the absence of forecasting errors—as they sought to build up their depleted reserves.

Although it is easy to identify districts most at risk because they received the most federal aid (as a percentage of pre-pandemic expenditures) or experienced the largest enrollment declines, it is difficult to identify the districts most at risk due to low fund balances. One could use budget forecasts for fiscal year 2026 (FY26) to assess projected fund balances after pandemic funding is set to expire, but this wouldn't take account of planned tax levies meant to sustain current spending (e.g., the replacement of expiring tax levies). There’s also the possibility that districts might inflate costs or understate revenues if they look to secure voter approval for a tax levy. So looking at forecasted FY26 cash balances could vastly overestimate the number of districts at risk. Nevertheless, by my calculations using May 2023 financial projections, if no districts passed levies ahead of FY26 and if projected expenses are accurate (both of which are doubtful), then 140 Ohio districts will have cash balances of under 10 percent of expenditures or less and 224 will have balances of less than 20 percent of expenditures.

Districts tend to be conservative when forecasting revenues relative to expenditures, typically by a magnitude of 2–3 percentage points during the period of our study (2009–16).[4] It seems to me that all districts should err on the side of being even more conservative than usual in their budget forecasts for FY26 and FY27. Post-ESSER budgets are a “known unknown,” as our study clearly documents the negative impact of budgeting uncertainties after federal funding runs out. Districts receiving a lot of federal aid should assume that there’s a good chance they’ll get their forecasts wrong because of the distortions that relief funds introduce.

Although my analysis focuses on revenue shortfalls that Ohio districts didn’t anticipate, it’s important to reiterate that shortfalls are often entirely predictable and of districts’ own making. That’s because districts often lack the political will and strength to manage their finances such that necessary spending cuts occur gradually. For example, a district experiencing declines in enrollment might continue to run under-enrolled buildings as long as possible to avoid upsetting local stakeholders by consolidating schools. In the case of pandemic funds, they might be waiting for the post-2025 budget shortfall before closing under-enrolled buildings or laying off staff, as stakeholders might be less likely to punish them for the closures when it comes in the wake of fiscal stress. Such political expediency may save the district some controversy and the wrath of teachers unions—at least for a time—but it comes at the expense of kids’ learning and wellbeing. If done gradually and carefully, however, the closure of low-performing schools and the layoff of ineffective or unnecessary staff can even improve student learning.

Districts are likely making major errors in forecasting future revenues (a “known unknown”), and many have taken on financial obligations they know they can’t afford (a “known known”). The former requires conservative revenue forecasting to mitigate risk, and the latter requires that districts phase in spending cuts immediately to avoid the negative impact of making sudden larger cuts down the line. My research on Ohio districts in the wake of the Great Recession makes clear that students will suffer if districts fail to act accordingly.

Stéphane Lavertu is a Senior Research Fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and Professor in The Ohio State University’s John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs or The Ohio State University.

[1] The final batch of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds must be obligated by September 30, 2024, the end of the 2024 federal fiscal year. The funds must be spent (“liquidated”) by January 20, 2025, though districts can apply for extensions so long as funds are obligated by the deadline.

[2] This figure includes non-ESSER funding sources. See page 46 of their May 2023 financial forecast.

[3] Stéphane Lavertu and Travis St. Clair. (2018). “Beyond spending levels: Revenue uncertainty and the performance of local governments” Journal of Urban Economics 106: 59-80. The pre-print version available here. Published version is here.

[4] Research has documented that both state and municipal governments systematically (and often purposefully) under-forecast revenues by a similar magnitude.

- Gongwer covered the news of the massive parental response to expanded EdChoice voucher eligibility. I include this subscriber-only content because of the statements of the OEA boss (which provides our title today) and the comments from our own boss Chad Aldis (yes, he is), which are based far more in reality. I know soliciting parent comments is probably not the wheelhouse of the Statehouse news gatherers, but this feels to me like an instance where the full story could have used an additional dose of reality of just that sort. (Gongwer Ohio, 9/8/23)

- Also out there dropping reality bombs is our Aaron Churchill. A previous blog of his—on the topic of how Ohio can successfully implement the science of reading—morphed into an op-ed published yesterday. (Tribune Chronicle, 9/10/23)

- I try not to deal with politics too much in these clips (icky), but I will go so far as to say that there are some very clear and distinct choices here for school board voters in Berea, based on the candidates’ answers to these basic questions. If I do say so myself. (Cleveland.com, 9/8/23)

- The number of non-English speaking students in Springfield City Schools has more than quadrupled in the last four years, including hundreds of newcomers from Haiti. These include French speakers as well as the less-common (to us Americans, that is) Haitian Creole speakers. Here’s a detailed look at how the district has been adding resources and staff to help students become fluent in English as quickly as possible and to give multi-lingual supports to them and their families until then. Kind of nice. (Springfield News-Sun, 9/11/23)

- Yep. You guessed it: No progress in talks so the Youngstown teachers strike continues (along with remote learning for students who are bothering, thanks for asking). Talks are to resume today at 3 pm, with that pesky ADC language still said to be the sticking point. Honestly: I thought I was the only one clinging to that desiccated construct in the year of our lord Mohip 2023. (WFMJ-TV, Youngstown, 9/11/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

High on the list

A number of charter schools across the country fared well on U.S. News & World Reports’ list of top high schools in America, released last week. This includes The Signature School in Evansville, Indiana, which was ranked number 2 in the country. Amazing! You can check out Ohio’s charter school rankings here (kudos to KIPP Columbus for being highest rated in the state) and see the full list of high schools here.

Working for students

Here’s a nice look at North Dayton School of Discovery, whose leaders and community partners discuss their all-out efforts to help students to catch up and move forward following years of pandemic-related disruptions to their education.

School and community Pt 1

Utica Shale Academy recently opened its brand new community center in Salineville, Ohio. While it provides needed workout facilities for USA students, it is also open to the public as a recreation/community center in the small Appalachian town and is just one of a wide range of projects designed to further integrate the school and the community.

School and community Pt 2

Building a new community from bare ground is a complicated undertaking. But the planners behind SoLé Mia, now rising in Florida, seem to be thinking of everything. After recently announcing plans to include a medical center for residents, they have also announced a charter school will be part of the community as well. A new campus of Mater Academy (which has schools around the country including Columbus) is projected to open in fall of 2025 as the new city rises and grows.

Charter grad speaks out

Former charter school student (and valedictorian and graduate) Alfonso Narvaez had a pointed message for Toledo City Council members who voted against a permit for expansion of a charter in Toledo recently. In his letter to the editors of the Blade, Narvaez expresses his belief that the downvotes were the result of animus toward charter schools, ignoring the benefit that the proposed new daycare and preschool would bring to the city. “At the end of the day we hurt local businesses,” he writes, “but more importantly, we could be effectively harming some child’s future because of political loyalty.”

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.