- The yawning gap in life expectancy between high school grads and dropouts is more complicated than some narratives imply. —Dylan Matthews, Vox

- Florida approved usage of the CLT, a classical alternative to the SAT and ACT, but the fledgling test remains unproven. —Nick Anderson, Washington Post

- One columnist’s experience getting kicked out of school for lying about her address so she could attend a better school. —Barbara Martinez, Mosaic

- As student enrollment declines, districts face school closures and questions about what to do with vacant buildings. —Bloomberg

For many years, the conventional wisdom in the field was that grade retention was a bad idea. A 1997 opinion piece in Education Week titled “Grade retention doesn’t work” reflected the prevailing sentiment in the education community and the available research evidence at that time: retained students performed worse than their promoted peers in the years that followed.[1] This brief challenges that notion, based on more recent studies that do a better job of isolating the causal effect of retention.

Download the full brief or read it below.

Executive Summary

Key Questions

Can grade retention be beneficial for students?

Answer: Yes. Several recent studies have found that retention in elementary school can be beneficial for students in improving middle school outcomes when the students most likely to benefit are identified and retention is paired with appropriate instructional supports.

What risks are associated with retention?

Answer: There is evidence that students who are retained in middle school are less likely to graduate high school or enroll in college, suggesting that intervening sooner is a safer course.

Is grade retention too costly for school systems?

Answer: Not necessarily, because the long-term costs school systems actually incur could end up being only a fraction of the cost of an additional year of schooling.

The Bottom Line

Retention is more likely to succeed in elementary grades and when coupled with instructional supports that are tailored to the educational needs of retained students.

Recommendations

1. Ensure that retention policies target elementary school, as opposed to middle school.

2. Provide individualized support for students as soon as the risk of retention becomes apparent and continue supporting those who are nevertheless retained.

3. When assessing the cost effectiveness of retention policies, consider the long-term costs, the possible benefits for retained students, and the potential for positive spillovers.

Introduction

In the twentieth century, education researchers conducted dozens of studies of “discretionary grade retention,” which occurs whenever teachers, parents, and/or principals use their individual or collective discretion to require a student to repeat a grade. High-profile meta-analyses based on these studies concluded that grade retention was associated with poorer academic outcomes (including higher dropout rates) and greater risk of behavioral issues.[2] However, the studies included in these meta-analyses were mostly correlational rather than causal.

Despite these negative findings, concerns about “social promotion,” as well as the increasing popularity of accountability and standardized testing, led to the implementation of universal and theoretically mandatory retention policies in many states and school districts. A decade after President Clinton’s 1998 call to end social promotion, at least six states and twelve large school districts had adopted test-based promotion policies, whereby students had to score above minimum thresholds on standardized tests to advance to the next grade level. By 2020, about half of states required or encouraged school districts to retain students whose third-grade reading scores showed they were struggling to meet basic standards.[3]

The use of test-based promotion policies, including the requirement that retention decisions be based on a clearly defined cut score, allowed for a more rigorous examination of the causal effects of grade retention. As a result, a new and extensive literature has emerged over the past two decades that paints a much more nuanced picture of grade retention and its consequences. This recent work uses methods that focus on students scoring near the test-score cutoffs around which the promotion or retention decision has been made, and the effects we discuss are applicable to the students scoring at this decision threshold.

Question 1: Can grade retention be beneficial for students?

Contrary to the conventional wisdom in education circles, recent research suggests that retention in earlier grades can benefit students. For example, recent studies from Florida,[4] Indiana,[5] Mississippi,[6] Chicago,[7] and New York City[8] provide evidence that grade retention in elementary school (generally in grades 3–5), when implemented as part of a broader remediation effort, can increase test scores through middle school and reduce the need for future remediation.[9] Retention in elementary school may also increase the likelihood that students take advanced courses in middle and high school.[10] Furthermore, new evidence suggests that these academic benefits may be substantially larger for students with lower baseline achievement at the time of retention.[11]

In addition to these academic benefits, evidence from descriptive surveys indicates that students retained in elementary school reported a greater sense of school connectedness,[12] lasting several years beyond retention, than comparable students who were promoted. However, research on the effect of grade retention on disciplinary outcomes is skimpy and mixed, with one study finding a short-lived increase[13] in suspensions and the other finding a similarly short-lived decline.[14]

Research also suggests that retention is more likely to succeed when paired with instructional supports that are tailored to the educational needs of students identified as potentially at risk for retention. In fact, all the studies that have found positive effects of retention were of policies that included supplemental instruction for retained students. For example, Florida’s third-grade retention policy, which has provided the blueprint for early grade-retention policies in many other states,[15] requires schools to (1) develop academic improvement plans for students that specifically address their learning needs, (2) assign these students to high-performing teachers, (3) provide at least ninety minutes of daily reading instruction, and (4) offer summer reading camp at the end of the year that facilitates intensive reading intervention lasting between six and eight weeks for all students who scored below the retention cutoff. Similarly, in New York City,[16] Indiana, and Mississippi, both retained and at-risk elementary students who were ultimately promoted received instructional support. It is unlikely that retention alone, without such additional instructional help, would produce similar benefits.

Importantly, evidence suggests that providing supplemental services to at-risk students in the time prior to the promotion decision drastically reduces[17] the number of retained students. For example, when New York City’s policy was initiated for fifth graders, 22 percent of the first cohort was identified as at-risk of being retained. After exposure to a dedicated set of academic intervention services throughout the school year, only 3 percent of the cohort was ultimately retained. Later cohorts, who were exposed to the policy’s intervention services in earlier grades, saw a large reduction in the proportion of students needing intervention services upon entry to fifth grade.

Retention policies that identify students who are likely to benefit from retention are also more likely to succeed. For example, under Florida’s legislation, low-performing third graders are exempt from retention if they have certain disabilities and have been already retained once; if they have received intensive reading remediation for two years and have already been retained twice; if they have been in the English-learner program for less than two years; if they can perform at an acceptable level on an alternative reading assessment approved by the State Board of Education; or if they can demonstrate proficiency through a teacher-developed portfolio.

Similarly, establishing the right criteria for promotion is important because retention may be less effective for relatively higher-performing students and because retaining too many students may hinder schools’ ability to provide the necessary instructional support. For example, one study finds that students just above Florida’s retention cutoff as well as low-performing students who were exempt from the policy would have been less likely to benefit from retention had they received it.[18] In other words, Florida’s retention policy may be successful in part because it endeavors to identify the students who are likely to benefit.

In short, recent research has shown that grade retention in elementary school can increase test scores through middle school and reduce the need for future remediation. It is most likely to succeed when it is supplemented with individualized instructional support as soon as the risk of retention becomes apparent and when the students who are ultimately retained are the students who are likely to benefit from the experience.

Question 2: What risks are associated with retention?

While the evidence on grade retention in the elementary grades has become increasingly positive, the research on retention in middle school grades remains negative. Despite the fact that the structure of middle school retention policies has generally mirrored that of elementary retention policies, including requirements for demonstrating a minimum proficiency on applicable state assessments and instructional supports, overall the research on these policies suggests little or no effect on academic achievement and higher levels of student disengagement.[19] For example, students retained in middle school are less likely to graduate from high school[20] and more likely to drop out.[21] Additional evidence from Louisiana finds that students retained in eighth grade are less likely to enroll in college[22] and more likely to be involved in criminal activity as adults.[23]

Although additional research is needed to understand why negative impacts are more likely to occur when retention is implemented in the higher grades, one common argument against grade retention policies is that they place a significant emotional burden on students: because students can be stigmatized as failing and must adjust to a new peer group, they may feel singled out and disengage from schooling.

One factor that might exacerbate these unintended consequences is inconsistent enforcement of retention policies. After all, despite the important role that test scores play in twenty-first-century retention policies, because many students receive exemptions, only a fraction of students who are identified for retention based on their test scores are actually retained.[24] While these exemptions could help schools avoid retaining students who are less likely to benefit from retention, discretionary exemptions (such as using portfolios of student work) can also lead to differential policy enforcement[25] because parents from more advantaged backgrounds are more likely to advocate for (and succeed in) avoiding retention, which could contribute to feelings of being excluded or singled out for retained students, especially among traditionally marginalized groups. While differential enforcement is also a concern for earlier grade retention, the negative academic effects found for middle school retention, such as lower graduation rates, do not materialize in the earlier grades.

In short, available evidence indicates that retention in middle school grades is less likely to succeed. This is perhaps because it leads to feelings of being singled out; however, the reasons why middle school grade retention is not as successful requires further study.

Question 3: Is retention too costly for school systems?

Another criticism of grade retention is that it is expensive for school systems because schools must offer an additional school year to retained students. However, to make an informed decision, policymakers must consider the long-term benefits of retention, as well as the timing of the costs.

Recent studies suggest that the long-run cost of early grade retention is only a fraction of the cost of an additional year of schooling[26] because retained students are significantly less likely to be identified for remediation or retained again in later grades.[27] And conversely, students who are at risk of retention but are ultimately promoted often take longer than four years to graduate high school.[28]

As noted, in addition to these fiscal offsets, there is evidence that (in addition to boosting middle school test scores) early grade retention increases the likelihood of taking college-credit-bearing courses in high school, potentially better preparing students for college-level coursework.[29] Furthermore, many cost-effectiveness calculations also ignore the potential for spillover effects. For example, the threat of retention could improve outcomes for a broad set of students, as may have happened in Florida, where the share of first-time third graders scoring below the retention cutoff dropped from 21 percent to 14 percent in the first five years of implementation.[30] Logically, this change was very likely driven by improved learning experiences for students in earlier grades and during the third-grade year, rather than retention itself. Finally, the threat of retention could lead parents to reallocate their resources (whether in the form of time or money) to avoid the retention of their children. For example, new evidence suggests that the benefits of early grade retention can spill over to the younger siblings of identified students, in part because parents are more likely to move their younger child to a higher-performing school when the older sibling is identified for retention.[31]

From a public policy perspective, all these spillover effects are “free” and as such may have profound effects on the cost effectiveness of early grade-retention policies. The overwhelming majority of students aren’t retained, so even a small spillover effect on the educational outcomes of students not targeted by the policy (e.g., their siblings or their peers not at risk of retention) could offset the costs associated with retention. In short, it is important for policymakers to weigh the long-term benefits of retention and the likely spillover effects on nonretained students against the likely costs.

***

Despite the volume of research on grade retention, we have much to learn. For example, the long-term effects of early grade-retention policies are not well understood, and there is potential for the effects experienced in middle school to dissipate. We need more research on how early grade retention affects students with lower baseline achievement and/or other educational needs, because some evidence suggests that effects could be substantially different for this population.[32] In addition to these gaps, we still know little about the spillover effects of early grade-retention policies on other students (though what we do know seems promising). Finally, additional research is needed to better understand the reasons for the seemingly negative impacts of grade retention in middle school.

The Bottom Line

Empirical research in the twenty-first century provides substantial evidence that grade retention in elementary school can be an effective lever for improving student outcomes. But school and district leaders should absorb the full lessons of the past two decades: waiting until middle school, retaining kids without providing the necessary supports, or failing to identify the students most likely to benefit are unlikely to yield the desired results and could even lead to adverse effects.

Recommendations

1. Ensure that retention policies target elementary school, as opposed to middle school.

2. Provide individualized support for students as soon as the risk of retention becomes apparent and continuing support to those who are nevertheless retained.

3. When assessing the cost effectiveness of retention policies, consider the long-term costs, the possible benefits for retained students, and the potential for positive spillovers.

Endnotes

[1] Arthur J. Reynolds and Judy Temple, “Grade retention doesn’t work,” Education Week, September 17, 1997, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-grade-retention-doesnt-work/1997/09.

[2] Charles T. Holmes, “Grade level retention effects: A meta-analysis of research studies,” in Flunking grades: Research and policies on retention, eds. L. A. Shepard and M. L. Smith (London: Falmer Press, 1989), 16–33; and Shane R. Jimerson, “Meta-analysis of grade retention research: Implications for practice in the 21st century,” School Psychology Review 30, no. 3 (September 2001): 420–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2001.12086124.

[3] Education Commission of the States, “50-state comparison: State K–3 policies,” https://www.ecs.org/50-state-comparison-state-k-3-policies-2023.

[4] Guido Schwerdt, Martin R. West, and Marcus Winters, “The effects of test-based retention on student outcomes over time: Regression discontinuity evidence from Florida,” Journal of Public Economics 152 (August 2017): 154–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.06.004.

[5] NaYoung Hwang and Cory Koedel, “Holding back to move forward: The effects of retention in the third grade on student outcomes” (EdWorkingPaper no. 22-688, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, December 2022), https://doi.org/10.26300/mmxx-3e82.

[6] Kirsten Slungaard Mumma and Marcus A. Winters, “The effect of retention under Mississippi’s test-based promotion policy” (working paper 2023-1, Wheelock Educational Policy Center at Boston University, Winter 2023), https://doi.org/10.26300/hq2t-7x64.

[7] Brian A. Jacob and Lars Lefgren, “Remedial education and student achievement: A regression-discontinuity analysis,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 81, no. 1 (2004): 226–44, https://doi.org/10.1162/003465304323023778.

[8] Louis T. Mariano and Paco Martorell, “The academic effects of summer instruction and retention in New York City,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 35, no. 1 (March 2013): 96–117, https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373712454327.

[9] Jay P. Greene and Marcus A. Winters, “Revisiting grade retention: An evaluation of Florida’s test-based promotion policy,” Education Finance and Policy 2, no. 4 (2007): 319–40, https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp.2007.2.4.319; and David Figlio and Umut Özek, “An extra year to learn English? Early grade retention and the human capital development of English learners,” Journal of Public Economics 186 (June 2020): 104184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104184.

[10] Figlio and Özek, “An extra year to learn English?”

[11] Isaac M. Opper and Umut Özek, “A global regression discontinuity design: Theory and application to grade retention policies” (EdWorkingPaper no. 23-798, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, June 2023), https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai23-798.pdf.

[12] Vi-Nhuan Le, Louis T. Mariano, and Al Crego. “The Impact of New York City’s Promotion Policy on Students’ Socio-emotional Status.” In: Ending Social Promotion Without Leaving Children Behind: The Case of New York City, eds. Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Sheila Nataraj Kirby, and Louis T. Mariano (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009).

[13] Umut Özek, “Hold back to move forward? Early grade retention and student misbehavior,” Education Finance and Policy 10, no. 3 (2015): 350–77, https://doi.org/10.1162/EDFP_a_00166.

[14] Paco Martorell and Louis T. Mariano, “The causal effects of grade retention on behavioral outcomes,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 11, no. 2 (2018): 192–216, https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2017.1390024.

[15] Amy Cummings and Meg Turner, “COVID-19 and third-grade reading policies: An analysis of state guidance on third-grade reading policies in response to COVID-19” (policy brief, Education Policy Innovation Collaborative, October 2020), https://epicedpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/RBG3-Reading-Policies-FINAL-10-29-20.pdf.

[16] Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Scott Naftel, Gina Schuyler Ikemoto, Catherine DiMartino, and Daniel Gershwin. “School-Provided Support for Students: Academic Intervention Services.” In: Ending Social Promotion Without Leaving Children Behind: The Case of New York City, eds. Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Sheila Nataraj Kirby, and Louis T. Mariano (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009).

[17] Sheila Nataraj Kirby, Scott Naftel, Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Daniel Gershwin,and Al Crego. “Performance of 5th Graders in New York City and Overall Performance Trends in new York State.” In: Ending Social Promotion Without Leaving Children Behind: The Case of New York City, eds. Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Sheila Nataraj Kirby, and Louis T. Mariano (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009).

[18] Opper and Özek, “A global regression discontinuity design.”

[19] Julie A. Marsh, Daniel Gershwin, Sheila Nataraj Kirby, and Nailing Xia, Retaining students in grade: Lessons learned regarding policy design and implementation (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009), https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR677.html.

[20] Brian A. Jacob and Lars Lefgren, “The effect of grade retention on high school completion,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1, no. 3 (July 2009): 33–58, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.1.3.33.

[21] Louis T. Mariano, Paco Martorell, and Tiffany Berglund, The effects of grade retention on high school outcomes: Evidence from New York City schools (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1259.html.

[22] Matthew F. Larsen and Jon Valant, “Fuzzy difference-in-discontinuities when the confounding variation is sharp: evidence from grade retention policies,” Applied Economics Letters 30, no. 15 (2023): 2009–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2089339.

[23] Ozkan Eren, Michael F. Lovenheim, and H. Naci Mocan, “The effect of grade retention on adult crime: Evidence from a test-based promotion policy,” Journal of Labor Economics 40, no. 2 (April 2022): 361–95, https://doi.org/10.1086/715836.

[24] For example, in the first year of Florida’s third-grade retention policy, one-third of students who scored below the cutoff were promoted because they received exemptions. This number increased to 55 percent in the fifth year of the policy. See Christina LiCalsi, Umut Özek, and David Figlio, “The uneven implementation of universal school policies: Maternal education and Florida’s mandatory grade retention policy,” Education Finance and Policy 14, no. 3 (2019): 383–413, https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00252.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Marcus A. Winters, “The cost of retention under a test-based promotion policy for taxpayers and students,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (2022): https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737221138041; and Mariano, Martorell, and Berglund, The effects of grade retention on high school outcomes.

[27] Figlio and Özek, “An extra year to learn English?”; and Schwerdt, West, and Winters, “The effects of test-based retention on student outcomes over time.”

[28] Mariano, Martorell, and Berglund, The effects of grade retention on high school outcomes.

[29] Figlio and Özek, “An extra year to learn English?”

[30] LiCalsi, Özek, and Figlio, “The uneven implementation of universal school policies.”

[31] David N. Figlio, Krzysztof Karbownik, and Umut Özek, “Sibling spillovers may enhance the efficacy of targeted school policies” (working paper 31406, National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2023), https://doi.org/10.3386/w31406.

[32] Opper and Özek, “A global regression discontinuity design.”

Acknowledgments

This brief was made possible through the generous support of our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. We are deeply grateful to authors Umut Özek and Louis Mariano for their knowledgeable and unbiased approach to this important subject. We also extend our gratitude to external reviewer Marcus Winters for his insightful feedback on early versions of the brief, and to Pamela Tatz for copyediting the final report. At Fordham, we would like to thank Chester E. Finn, Jr., Michael J. Petrilli, Amber M. Northern, and David Griffith (who also managed the project) for reviewing drafts; Victoria McDougald for her role in dissemination; and Stephanie Distler for developing the report’s cover art and coordinating production.

Public-sector collective bargaining—whereby governments negotiate with employee unions over compensation and management practices—has enabled teachers unions to put a stranglehold on Ohio school districts. Research has clearly established that unions across the U.S. have a profound influence on K–12 education, in large part because of their outsized influence on politics at all levels of government. That’s no different here, as state collective-bargaining law has made teachers unions particularly influential in Ohio schools.

Ohio was late to the game in granting collective-bargaining rights to public-sector employees, but it eventually enacted the “the strongest public-sector employee statute in the nation.” The Ohio Public Employee Collective Bargaining Act of 1983 made it easy to establish a union representative for a bargaining unit (e.g., only 50 percent of district employees had to vote affirmatively for the state to certify the representative); required school districts to bargain with that union representative using mutually agreed procedures (which the state enforced with a powerful new government agency); prescribed mediation procedures that essentially split the difference between union and district preferences during negotiations; and provided certain public employees (notably teachers) the right to strike if mediation failed—a source of significant bargaining power for unions. So, although the law merely permitted collective bargaining, these features led teachers in the vast majority of Ohio districts to establish union representation and negotiate collective-bargaining agreements by 1990.

Today, nearly all Ohio school districts have collective-bargaining agreements on file with the State Employee Relations Board. These agreements typically last three years and can deal with virtually all aspects of school district management. Most prominently, they establish rigid pay schedules that set teacher salaries according to seniority and degrees, and they prescribe, in detail, staff benefits, such as health insurance and leave time. They also set teachers’ work conditions, such as maximum class size, how their performance will be evaluated, how much time they have each day to prepare lessons or eat lunch, and so on. What has gotten perhaps the most attention is how thoroughly they prescribe personnel management practices, such as strict procedures that make it almost impossible to fire incompetent teachers or to assign effective teachers to schools and students that need them the most. I encourage anyone to look over their local district’s teacher collective-bargaining agreement (available here, by downloading the version for bargaining unit “T”) to get a sense for just how prescriptive these contracts are and how little management discretion they allow school leaders.

In spite of what a “balanced” accounting of political debates might have you believe, rigorous research consistently finds that the management constraints that teachers unions impose via collective bargaining have a negative impact on student outcomes.[1] For example, student achievement declines when collective-bargaining agreements become more restrictive, and states’ adoption of collective-bargaining laws led to declines in cognitive skills and earnings. Most relevant, Yale Professor Barbara Biasi's analysis of Wisconsin’s Act 10—which rolled back some collective-bargaining rights, including disallowing the establishment of rigid pay schedules through collective-bargaining agreements—indicates that districts with newfound flexibility were able to increase pay and recruit more effective teachers. Importantly, these changes led to significant increases in student achievement.

Wisconsin’s collective-bargaining reform was disruptive in initial years, as many teachers retired early to secure retirement benefits, districts competed over a limited supply of effective teachers, and ineffective teachers left the profession. But economist E. Jason Baron, who documented the initial negative impacts, later completed a follow-up study in which he found that four years after its implementation, Act 10 eventually led to a 20 percent increase in the number of teaching degrees awarded by selective schools (defined by their acceptance rates and students’ ACT scores) and improved student achievement by that same magnitude.[2] His research suggests that, by enabling districts to sharply increase the wages of promising entry-level teachers, more talented individuals went into teaching, and in turn, student achievement increased significantly across the state.

My 2021 study with Jason Cook (a professor at the University of Utah) and Corbin Miller (an economist at the U.S. Department of the Treasury) found that Ohio districts also benefited when union influence was limited.[3] Using a rigorous, plausibly causal research design, we found that when collective bargaining enabled Ohio teachers unions to meddle in districts’ allocation of funds (because new revenue arrived at the same time collective bargaining was taking place), teacher pay increased but student achievement did not. When unions were less able to meddle (again, because of the timing of revenue increases relative to collective bargaining), teacher pay did not increase but student achievement did. The take-home point of our study is this: Collective bargaining led districts to spend money in ways that yielded no discernable benefits in terms of academic outcomes, and it may have imposed financial obligations that required them to obtain yet more revenue from local taxpayers.[4]

What collective-bargaining reform should entail

The rigorous studies on Wisconsin’s Act 10 suggest that, at minimum, Ohio should disallow collective bargaining over compensation schemes. The research convincingly shows that providing districts the authority to negotiate pay with individual teachers can yield substantial academic benefits while strengthening the teaching profession. Specifically, Wisconsin’s Act 10 limited collective-bargaining negotiations to inflation adjustments to base wages; other changes to compensation were up to the districts. In response, about half of districts decided to eliminate rigid salary schedules that compensated teachers based on credentials and seniority. Districts that took advantage of this flexibility primarily adopted performance pay policies based on teacher evaluation ratings (not value-added test scores) and used bonuses to attract promising teachers in hard-to-staff positions. In other words, districts were able to direct resources toward individuals who best met their needs, as opposed to paying all district teachers the same rate regardless of their effectiveness or district needs.

My study links collective bargaining over teacher salaries to lower student achievement in Ohio, but it also suggests that any reduction in union influence over the allocation of district resources could improve student outcomes. For example, limiting Ohio teachers’ right to strike would reduce their bargaining power. Some of Wisconsin’s other reforms, such as disallowing dues deductions from employee paychecks and requiring unions to hold regular certification elections, could also serve this function. It is not clear, however, what impact these attempts to limit union power would ultimately have. Thus, although my study suggests any reduction in union bargaining power would provide districts with flexibility that might enable them to better meet kids’ needs, the most conclusive evidence points to the value of providing districts with discretion in determining teacher compensation.

Is there a path toward collective-bargaining reform in Ohio?

Ohio came close to reforming collective bargaining much like Wisconsin did. Shortly after Governor Scott Walker led the charge in Wisconsin, Governor John Kasich and the Ohio General Assembly enacted reforms to public-sector collective bargaining in 2011. Among other things, the Ohio law prohibited strikes by government workers, disallowed collective bargaining over healthcare and pensions, required performance-based teacher pay, eliminated agency fees, and lowered the vote threshold that public employees needed to reach to decertify their union. But, unlike Wisconsin, public-sector unions in Ohio prevailed when they secured a repeal of the law via a ballot initiative that same year. Ultimately, support for the repeal was bipartisan, which led to significant political moderation among Ohio lawmakers in subsequent years.

Given this humbling defeat, why should Ohio consider collective-bargaining reform now? First, low pay and teacher shortages have become policy concerns of both Democrats and Republicans. As the research above reveals, Wisconsin’s reforms to collective bargaining led to significant increases in pay and increased the recruitment of talented individuals to the profession. Second, pandemic-related learning loss is a very real threat to Ohioans’ economic well-being and should be a policy concern near the top of policymakers’ agenda. The research cited above clearly establishes that collective-bargaining reforms can lead to substantial increases in student achievement. Third, Ohio’s 2011 law affected all public employees (Wisconsin’s reforms focused primarily on teachers, as opposed to police and firefighters) and sought to impose cuts to compensation and benefits. The political feasibility of collective-bargaining reforms would be greatly enhanced if they focused primarily on education and if they were paired with Ohio’s considerable increases in school funding.

I want to emphasize that teachers are not the problem. Research leaves no doubt that they are by far the most important in-school educational input. Sadly, the state of the teaching profession has reached its lowest level in fifty years, as job satisfaction is low and the talented people we need in the classroom are less drawn to the profession. Ohio’s collective-bargaining law likely contributes to these problems, and reforming it could help solve them. Effective teachers are worth way more than they are paid right now, but school district leaders are unable to raise the pay of talented and hardworking teachers in a way that is commensurate with their contributions to student learning. That’s hardly a recipe for high morale and increased student achievement.

Stéphane Lavertu is a Senior Research Fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and Professor at The Ohio State University’s John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs or The Ohio State University.

[1] There is one fairly convincing 2020 study by Eric Brunner, Joshua Hyman, and Andrew Ju that finds that districts in states with stronger unions were more likely to increase school funding and teacher salaries, and that this higher funding corresponded to higher student achievement. However, the study cannot speak to whether achievement gains per dollar would have been greater in the absence of collective bargaining.

[4] The analysis also reveals that Ohio’s collective-bargaining agreements have become lengthier over time, from an average of 17,000 words in 1999 to over 24,000 words in 2019. Research indicates that the length of agreements is a decent proxy for how much they restrict district management.

Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein of California died on September 29. She was ninety years of age and remarkable in many ways, beginning with being the first woman to serve as mayor of San Francisco after her predecessor was assassinated in 1978.

She was also the first woman elected to the Senate from California (along with her colleague Barbara Boxer, elected in the same year), the longest-serving woman in the U.S. Senate, and the chamber’s oldest member at the time of her death. The New York Times obituary described her as “A tough campaigner who often embraced conservative ideas….”

Education Week called her “a pragmatic lawmaker who reached out to Republicans and sought middle ground.”

That middle ground was manifest in her tireless work with both Democrats and Republicans to ensure that families, especially those most in need, had more choices of schools for their children.

Feinstein was born in San Francisco on June 22, 1933, to a Jewish physician father, Leon Goldman, and a Catholic Russian American mother, Betty Rosenburg Goldman. She would attend and, in 1951, graduate from Convent of the Sacred Heart Catholic High School in San Francisco, as Sacred Heart Catholic High School was for boys only.

Feinstein would later recall that her enrollment in that Catholic high school was a difference-maker in her life. She could understand the plight of families who had no quality educational options in their own circumstances.

In 2003, much to the annoyance of the powerful California Teachers Association, Feinstein cast the deciding vote in the U.S. Senate to create the District of Columbia private school voucher program, which exists to this day.

Her support for this program raised broader issues among Democrats about the need for broad bipartisan support for what was then the emerging charter school movement and other education reform efforts. Those conversations inspired the creation a few years later of Democrats for Education Reform.

As a member of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee, she supported increased funding for charter schools. In 2022, this work earned her an award from the California Charter Schools Association. It described her as “among the most vocal and consistent supporters of charter public schools in the U.S. Senate for the past thirty years.”

She and South Carolina Republican Senator Tim Scott led the bipartisan 2022 effort to roll back the proposed rule from the U.S. Department of Education that would have placed restrictions on federal funding for charter schools. Their letter to the U.S. Secretary of Education, signed by two other Democratic Senators and three other Republican Senators, described how those changes would “not prioritize the needs of students and limits high quality choices to certain families.”

Her death is a loss to all those advocates working to give families and children more choices of schools, and to those families and children who now have the opportunity to exercise that choice. And more than anything else, her bipartisan approach to doing this will be missed and should inspire those who worked with her to continue that work.

For nearly two decades, Ohio’s EdChoice program has unlocked private school options for tens of thousands of students by offering state-funded scholarships. Students slated to attend low-performing schools have long been eligible for the financial assistance, and over the last decade, depending on their grade level, low- and middle-income students have become eligible, as well. In this year’s state budget bill, lawmakers expanded eligibility to include every student in the state, regardless of their assigned school or household income, with poorer families receiving larger scholarships than more affluent ones. In part because the program now covers private school students who hadn’t previously received state support, universal eligibility is expected to increase state expenditures on all scholarship programs from about $600 million in FY23 to $1.1 billion by FY25.

All this has further intensified the incessant complaining from private school critics, who are already suing the state over EdChoice. They continue to portray school funding as a zero-sum game, with the growth in scholarship support being framed as depleting the resources available to public schools. Dan Heintz, a school board member of Cleveland Heights-University Heights—a district that spent a whopping $23,000 per pupil in FY22—griped, “A billion dollars a year is being diverted to families using private schools.” Union boss Scott DiMauro of the Ohio Education Association muttered, “A dollar more for private school vouchers is a dollar less for public schools.” Tanisha Pruitt of the liberal, union-backed Policy Matters Ohio grumbled, “We're putting too much money into one system (private) while we're neglecting the other.”

The facts, however, simply don’t square with the rhetoric. Students in public schools continue to receive far more taxpayer support than scholarship students, and funding for the public school system has never been higher in Ohio. Moreover, state outlays for districts will continue to rise this school year and next. Hardly the “neglect” or “diversion” that is regularly alleged. But don’t just take my word for it—here are the data.

Fact 1: School district funding easily outpaces scholarship amounts

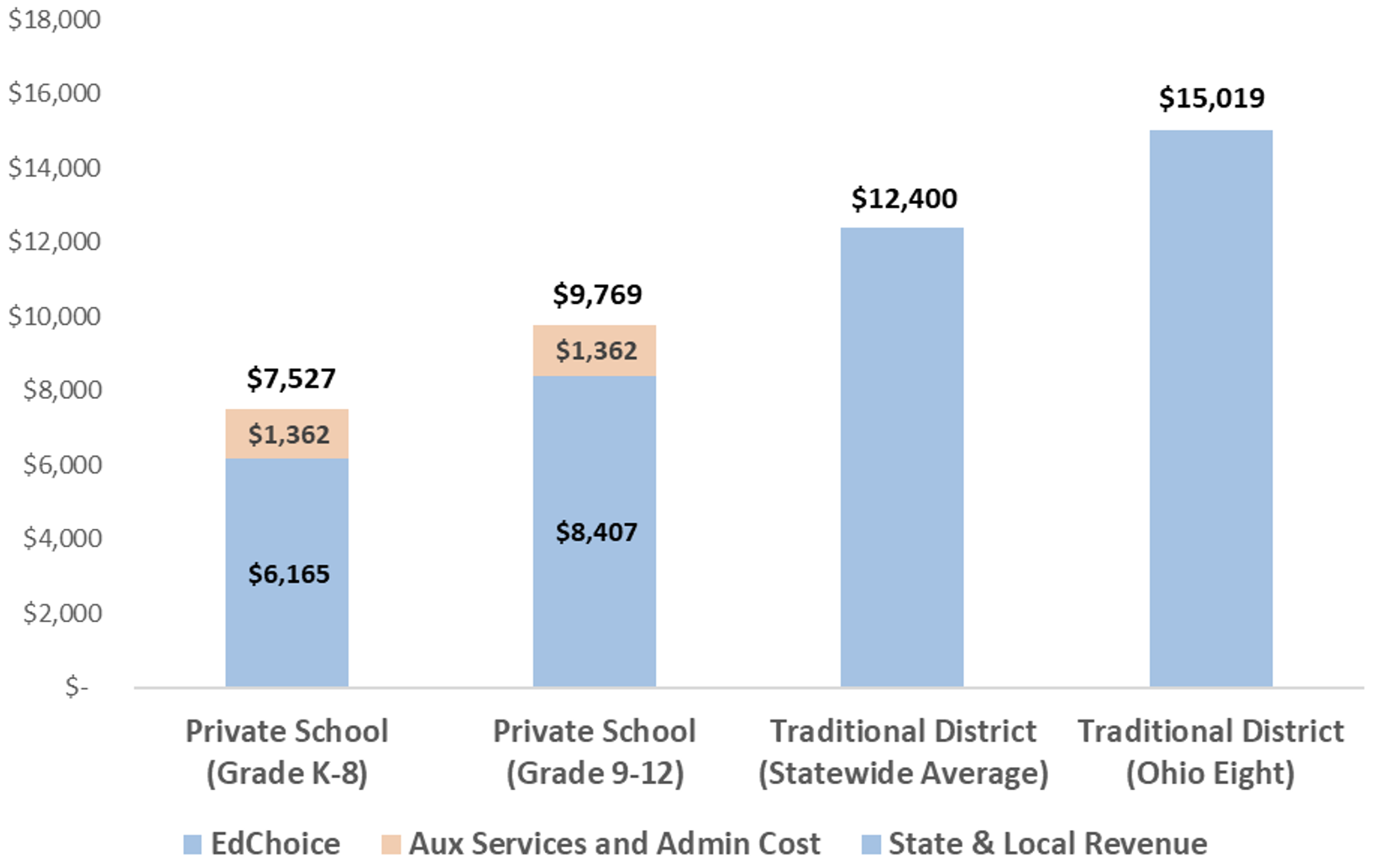

When examining the totality of taxpayer support for Ohio districts, it’s hard to say with a straight face that they are being shortchanged. Figure 1 shows overall taxpayer funding for districts statewide, as well as for the Ohio Eight districts—the places that have historically had the largest numbers of students using an EdChoice scholarship (the largest of the eight, Columbus, is also a plaintiff in the lawsuit). The district numbers include state and local taxpayer revenue,[1] the latter of which includes a minimum 20 mill (or 2 percent) state-required property tax. That baseline tax is accounted for in the state’s funding formula, thus explaining the relatively modest “direct” state aid that wealthier districts usually receive. The chart also displays the public subsidy for private-school students’ education, inclusive of both the current full EdChoice scholarship amounts and two small state funding streams that private schools receive (auxiliary services and administrative cost).

On average, districts statewide received $12,400 per pupil in state and local funding in FY22, well above the amounts for scholarship students who receive roughly $7,500 and $9,800 in public support depending on grade level. The Ohio Eight districts receive even higher funding than the average district (just over $15,000 per pupil). Thus, the funding differentials in Ohio’s big cities are quite large, with scholarship students—most of whom are likely from low-income households—getting the short end of the stick.

Figure 1: Private school (full scholarship amount) versus statewide district and Ohio Eight district per-pupil funding

Notes: The year of data used for this chart vary depending on data availability. EdChoice scholarship amounts are for FY24, while auxiliary services and administrative cost reimbursement totals are for FY23. The state and local revenue totals for traditional districts are from FY22, the most recent year of complete fiscal data (the differentials would be larger if more recent data were used). Average statewide and Ohio Eight transportation expenditures per pupil from FY22 are subtracted from district revenues, as they are responsible for providing transportation to private school students. The Ohio Eight districts are Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

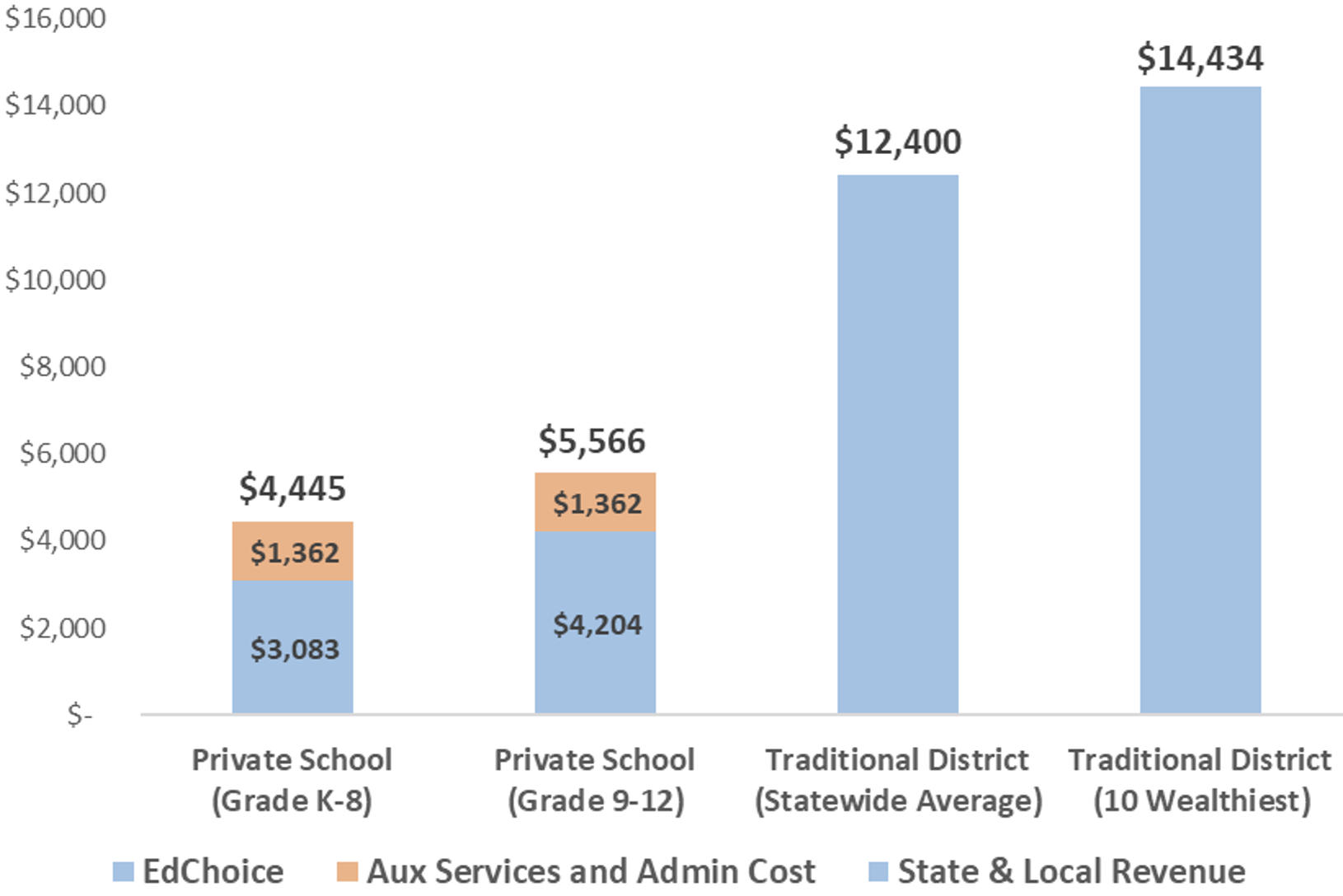

The funding differences tend to be even wider for wealthier students whose EdChoice scholarships are reduced via the sliding scale that lawmakers put in place as they expanded eligibility to all. For a student receiving a “half scholarship”—which would apply to families of four earning $165,000—their total public subsidy is about $4,500 for K–8 and $5,500 for high school. As figure 2 indicates, students attending one of the state’s wealthiest school districts receive more than $14,000 in taxpayer support. Arguably, it’s less critical to make up the gap for wealthier private school students, but the fact remains that state and local taxpayers far more heavily subsidize their public school counterparts’ education.

Figure 2: Private school (half scholarship amount) versus statewide district and wealthiest district per-pupil funding

Note: The ten wealthiest districts had the lowest percentages of economically disadvantaged students in FY22.

Fact 2. District funding continues to rise

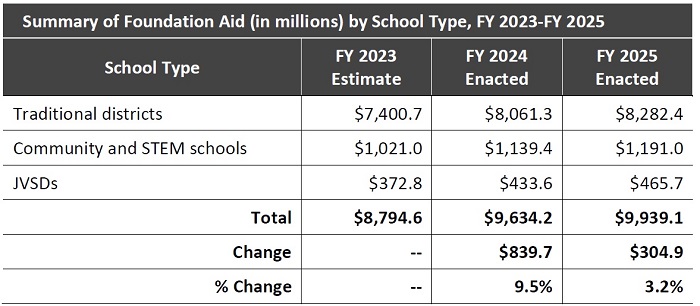

As noted above, some of the recent criticism of EdChoice centers on the increase in state outlays that helps fund universal eligibility, with the suggestion that districts’ funding was also somehow cut (“a dollar less for public schools”). But that’s nonsense. The table below appears in the Ohio Legislative Service Commission’s analysis of the enacted budget. It shows the aggregate “foundation aid”—the main pot of state money that is allocated to K–12 education—that school districts, public charter schools, and joint-vocational school districts (career-technical providers) receive this year and next.

It’s clear that district funding increases significantly over the biennium—from $7.4 billion in FY23 to $8.3 billion by FY25, amounting to a $882 million, or 12 percent, increase in state aid. If joint-vocational districts are added, the increase reaches $975 million over the biennium.[2] Bear in mind, too, that this total doesn’t even include the additional $170 million in state funding dedicated to early literacy initiatives and some $250 million more in career-technical education spending—all of which is non-foundation funding. The vast majority of those set-asides will go to traditional districts, leaving their total increase north of $1 billion. At the end of the day, state lawmakers grew the size of the pie for all types of Ohio schools. That’s something to cheer—not disparage.

Table 1: Increase in state spending for traditional districts in FY24–25

Source: Ohio Legislative Service Commission.

Fact 3. Ohio is spending record amounts on public schools

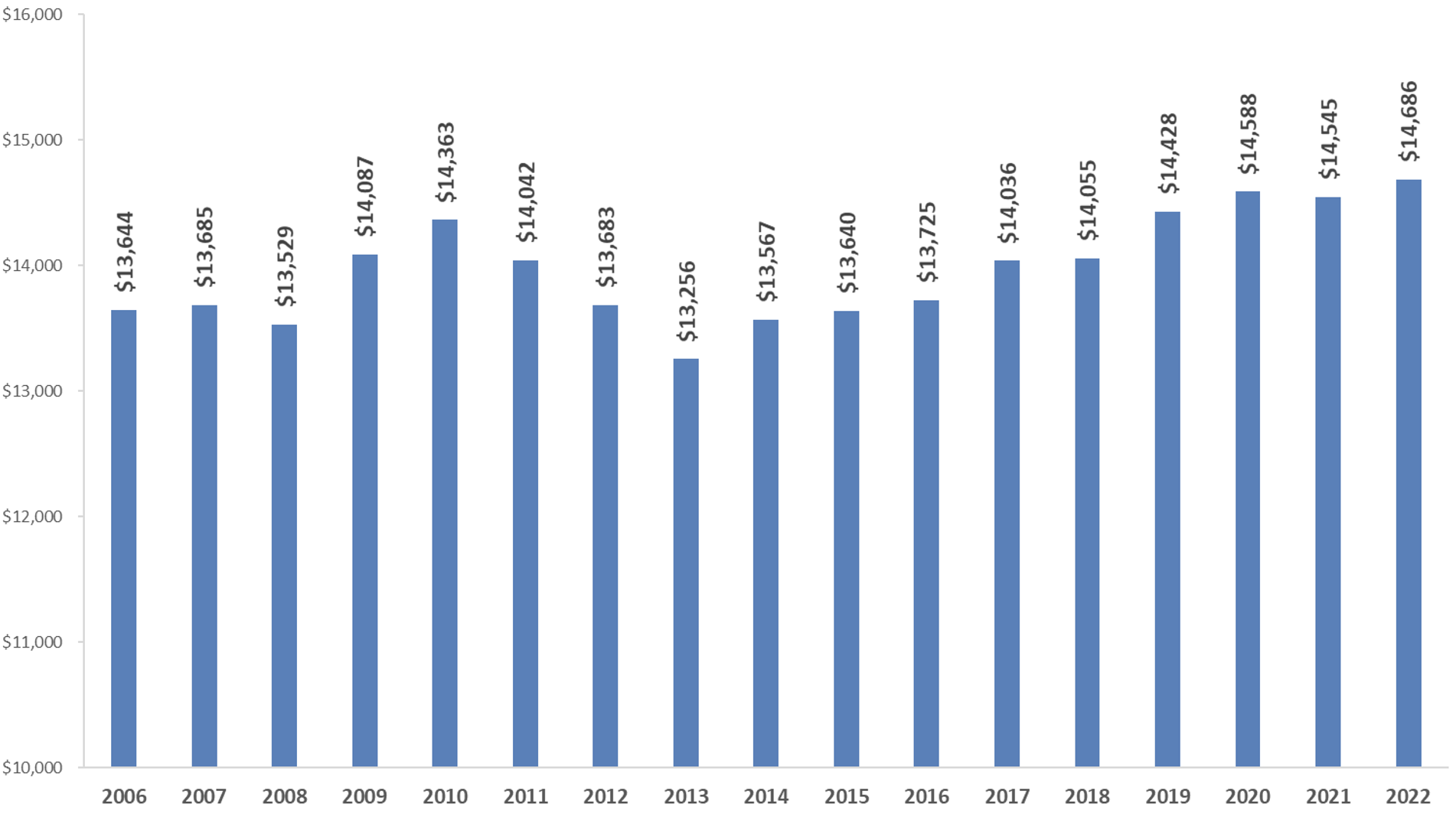

What is almost never said by private school opponents is the simple fact that Ohio spends more now—even adjusted for inflation—than it ever has on public schools. In FY22, average district spending reached $14,686 per pupil, the highest on record since 2006. My report from a couple years ago has spending data stretching further back—to 1990—and there is no year during the 1990s and early 2000s when spending was higher than in recent years. The long-term trend of increased public school spending is yet another indicator that public schools are not being systematically “defunded” as educational choice expands in Ohio. As additional evidence, a rigorous analysis of EdChoice’s fiscal impacts from its launch in 2006 to 2019 determined that growth in scholarship participation had no impact on districts’ per-pupil spending. Bottom line: Traditional districts now have more resources than ever to create the type of learning environments that help students succeed.

Figure 3: Per-pupil expenditures, Ohio public schools, 2006–2022

Note: Spending data from 2006–2021 are adjusted for inflation (to 2022 dollars) using the consumer price index. This chart relies on expenditure data (while figures 1 and 2 use revenue data) because, historically—until FY22—Ohio reported inflated per-pupil revenue data for some districts due to the former use of a “pass through” method to fund charters and most private school scholarships. Now that choice programs are “direct funded” from the state, districts’ per-pupil revenues are accurately reported as of FY22.

Celebrated free-market economist Thomas Sowell was recently asked what changed his mind about Marxism, and he promptly replied, “Facts. If you pay attention to them, you realize that they don’t square with what’s being said.” In our small corner of education policy in Ohio, some people are saying lots of things about school choice programs and their alleged impact on public school funding. But when we look more closely at the basic facts, their claims amount to nothing more than tall tales.

[1] I exclude districts’ federal revenues, which account on average for about 10 percent of total funding, as well as non-tax revenues (e.g., fees and sales of assets), to ensure a clearer picture of Ohio taxpayer contributions to education.

[2] Public charter schools are not usually seen as “traditional” public schools and are also a common target of the school establishment.

The bulk of commentary and school district policy relating to AI and education focuses almost exclusively on questions regarding cheating. What does it mean for a student—or an education columnist, for that matter—if a chatbot can write a ten-page essay in a matter of seconds? How can teachers assign any homework and know for certain who or what is actually completing it? These are real questions with which the education sector must wrestle.

But there are other risks of AI and thorny questions looming on the horizon that are worryingly overlooked. Student privacy is perhaps chief among them. This concern became real to me when I read the following theoretical example from renowned education scholar John Hattie:

You are a sixteen-year-old girl on your way to school. Just before you get to the school gates, you waver and decide you would rather go meet your friends at the mall. Your Robo-Coach has access to the messages you exchanged with your friends the previous evening, it can sense your elevated heart rate as you stop to consider the alternative course of action, and it notes from your GPS location and lack of speed that you have stopped at an unusual place. From the combined data, it assesses an 87 percent probability that you will not attend school, and it interjects with a timely and personalized nudge (in a soothing versus commanding tone; male versus female voice; using an emotional versus factual plea, etc.) to push you through the school gates.

Chronic absenteeism is a real crisis in education right now. Research has found that regular alerts sent to parents about missing assignments and absences can improve pass rates, attendance, and retention. But this technology relies on human operators. Regular updates are time intensive—parent phone calls that I’ve made have lasted an hour—when teachers, administrators, and office assistants have other pressing concerns.

AI could supercharge this basic intervention without any extra resources or time demands on already overburdened school staff. Imagine if thousands of potential dropouts received such messages or parents got a simple text every time their kid missed an assignment, failed a test, skipped a class, or received a detention. Even if such messages only influenced a small percentage of cases, across millions of students, that would be a substantial nudge in the right direction.

However—and here is where student privacy enters the equation—in order for this actually to work, any such software requires access to vast sums of private, personal data: messages, family history, GPS location, previous attendance records, and biometric and basic identifying information. AI software is only as good as the data on which it is trained. An essential infrastructure for AI to function well is information. If electricity needs power plants, AI needs data stores.

Modern large language models (LLMs) like Chat GPT, for example, are distinctly powerful because they have essentially read the entirety of the Internet. With trillions of examples of text, it is functionally a high-powered, predictive language machine. What word is likely to come next based on the topic at hand and the words that preceded it?

This general language capacity can then be honed through more specific datasets. Ask ChatGPT to consume educational research in the What Works Clearinghouse, for example, and the chatbot can become an expert pedagogical advice-giver. The better the data, the better the output.

At the fringes of this conversation, we approach what once seemed like science fiction. Some schools in China already require students to wear biofeedback headbands that send information to teachers about who is paying attention, who is angry, who is daydreaming, or who is drooling on their desk. Pair that with the recent advances in brain imaging that have produced relatively accurate text from brainwaves alone, and soon our own private thoughts will not be so private.

There are obvious concerns about data breaches, as when hackers accessed an online test-proctoring platform and subsequently leaked private information about 444,000 students. Similarly, glitches in a popular program that lets teachers view and control student screens would allow hackers to gain access to students’ webcams and microphones.

But I’m more concerned about a more abstract threat: How does constant surveillance affect the way we think, speak, and behave? French philosopher Michel Foucault popularized the concept of the Panopticon, a theoretical, circular prison with a watch tower in the middle that shines bright lights into exposed cells. Prisoners feel a constant sense of surveillance and so act as if they’re always being watched—fostering a compelled self-regulation into “proper” behavior.

What happens when our students really are being constantly monitored? A report from the National Association of State Boards of Education suggests that students are less likely to feel safe enough for free expression, and that these security measures “interfere with the trust and cooperation” and cast “schools in a negative light in students’ eyes.”

What district policies do to address student privacy concerns do not even begin to reckon with such threats. Gesturing at FERPA and warning students not to enter private information into LLMs, as Oregon has done, is insufficient, but at least the state has begun thinking through policies and recommendations. The next phase should be to develop sensible systems and regulatory frameworks that could handle these kinds of difficulties.

Software companies can create the skeletons of the tools to sell to districts, which already maintain private records. Consent forms could allow access to plenty more data, but such forms should be clear and understandable, not the inscrutable tomes that everyone currently ignores. Regulation must compel companies to collect only necessary data, limit their ability to sell this information, and dictate not just parameters for data collection and retention, but also deletion. There must also be aggressive legal consequences for firms that mishandle such data and suffer breaches.

But questions still remain: Will data stores like those held by the National Center for Education Statistics become public utilities? Will we need “freedom of thought” court rulings and regulatory frameworks in the coming years? Will student “credit scores”—currently created and tracked by some districts using AI software—get passed along to police when they graduate?

Asking these questions makes me feel like I’m a bit of a crazy person. But these are not issues to face in some distant future of some science fiction novel. Many are here now, and waving away generative AI as just another forgettable edu-tech promise risks exposing students to all of the hazards of AI without harnessing its potential benefits.

When Emerson Elliott passed away the other day at eighty-nine, surrounded by his loving four-generation family, one might simply say adieu and thanks to a capable and dedicated career federal civil servant—which he surely was. But that’s not the whole story and we—education folks especially—are in his debt for so much more.

That certainly goes for me. Emerson and I interacted off and on for half a century. I met him in 1969 when I was a junior White House staffer with some responsibility for education within the domestic policy team and he—just fourteen years out of Albion College but already a twelve-year veteran of the Bureau of the Budget (now OMB)—was in charge of the federal education budget. (His boss at the time was the late Dick Nathan, another distinguished public servant with whom I had the honor of crossing paths on multiple occasions.)

I was a callow youth. Em knew what he was doing. And like senior OMB careerists were (and are) supposed to, he participated fully in working groups and policy powwows, offering his best judgment as to what might work best to accomplish some desirable end, how much it might cost, what’s feasible and what’s not, what would need to change, and so on. Professional and neutral, to be sure, but also informed, insightful, and wise.

We would re-engage in a big way a decade and a half later, but during that interim, Emerson moved to the old Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, then the new Department of Education (and also took a breather for two years at George Washington University). Here’s a bit from his resume:

November 1982 to 1984: Director, Issues Analysis Staff, Office of the Under Secretary, Department of Education

June 1981 to October 1982: Director, Planning and Evaluation Service, Department of Education

February 1981 to May 1981: Consultant to the Secretary on legislation and Department organization

May 1979 to January 1981: Director, HEW School Finance Project

March 1978 to April 1979: Director, Educational Staff Seminar, George Washington University

August 1977 to February 1978: Practitioner in Residence, Institute for Educational Leadership, George Washington University

August 1972 to July 1977: Deputy Director, National Institute of Education.

May 1972 to July 1972: Associate Deputy Commissioner for Management, Office of Education, HEW

As you can tell from the “director” titles, Emerson had emerged as a leader, not just a doer or staffer.

We had various small-scale dealings during that period, but were thrown back together in 1985 when I joined Bill Bennett at ED as assistant secretary, heading what was then called the Office of Education Research and Improvement (OERI), precursor of today’s Institute of Education Sciences. As we put together a team to run this section of the Department, we realized both that it needed a full-scale reorganization, and also that its statistics unit—the National Center for Education Statistics—was sick: underfunded, neglected, abused, sluggish, underproductive, and nowhere near what had been envisioned as much as 120 years earlier when Congress created the original “department of education” to “gather statistics and facts on the condition and progress of education in the United States and Territories.”

Two years after A Nation at Risk, the dearth of up-to-date, high-quality education data was a serious problem for the nation. Bennett knew it, I knew it, Em knew it—and an expert panel declared that either NCES needed a total overhaul or should be put out of its misery.

Emerson at this point assumed a dual role, first as major advisor and strategist on a big reorganization of the whole of OERI (which Congress eventually okayed), and also as the first modern “Commissioner of Education Statistics,” responsible for directing NCES. But it was more than directing. It was also rebuilding that weak entity into a semblance of today’s multi-dimensional federal education statistics agency.

With Secretary Bennett’s blessing (though to the consternation of the heads of OERI’s other four units), we directed pretty much every extra appropriations dollar we could get into the NCES budget. But that wouldn’t have solved the problem without Em’s solid, focused, diplomatic-yet-firm leadership of the place, which inevitably extended beyond the agency itself into deft if usually quiet dealings with colleagues, Congress, and innumerable keen-eyed (and often hungry) outside constituencies.

While doing all that, he also served as an indispensable member of the little brain trust (along with Mike Kirst and myself) that did the heavy lifting for the Alexander-James task force that reinvented NAEP to become the semi-independent and generally respected arbiter of “how good is good enough” in the achievement of American K–12 students and the honest rapporteur of their performance at the national and state levels (and now in a number of big cities, as well.)

I stayed at ED into 1988, but Emerson remained NCES Commissioner until 1995, when, still in his early sixties, he retired from the federal civil service, having accumulated by then pretty much every prize and honor available to top performers in that line of work.

Whereupon he embarked on what amounted to a second career of research, writing, consulting, and advising for a host of education-related organizations, particularly the teacher-ed accreditation body known as NCATE and its successor, the Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Preparation (CAEP).

But there was much more. To quote again from his resume (which goes only to 2012):

Since leaving the Federal Government in 1995, consulting and advisory memberships have included: the U. S. Department of Education, National Educational Research Policy and Priorities Board; National Academy of Sciences panels on Bureau of Transportation Statistics, a feasibility study for a Strategic Education Research Program, the Board on Comparative International Studies in Education (chair), and a workshop on national education indicators; the Advisory Committee on Research and Development for the College Board; the Science Resources Studies Advisory Committee of the National Science Foundation; the advisory panel for “Measuring Up” indicators published by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education; an evaluation of the Delta Cost Project for use by its Board to make long term strategic decisions; and education indicators for the State of the USA key national indicators project.

Most recently, Em and I reconnected in 2020 as I embarked on a book about NAEP’s history and current challenges and sought to consult his memory on various issues. Though well into his mid-eighties and soon headed toward what would become his final illness, he responded promptly, generously, and far beyond my expectations. He basically read every word of my manuscript, especially the history parts, amplified and corrected the facts, engaged respectfully on a number of touchy issues, and even used this occasion to rethink some longstanding points of tension between the “NAGB view” and the “NCES view” on key topics such as NAEP’s “achievement levels” (basic, proficient, advanced). It’s scarcely surprising that Emerson’s name appears on multiple pages of that volume, as well as in the acknowledgments.

I can’t claim that we were ever close friends. But I do assert, without fear of contradiction, that we were fortunate, as education folks and as Americans, to benefit from six decades of the highest-quality professionalism, conscientiousness, and near-perfect instinct for what would be best and work best and yet be doable from this remarkable public servant. May he rest in peace.

There is plentiful research suggesting that, among in-school factors, teachers consistently matter the most when it comes to student testing outcomes. On average, those with more experience and better prior preparation are likely to produce larger learning gains. Plus, teachers’ licensure status and their scores on licensure tests are positively linked to those gains. But this existing research is almost entirely focused on academic subjects such as math and English language arts (ELA). Enter a group of (mostly) CALDER researchers seeking to determine whether those patterns also hold in the realm of career and technical education (CTE).

Their data come from Massachusetts, which has led the way in building a robust CTE infrastructure and making an array of courses readily accessible to students in urban, suburban, and rural areas. The Bay State has notched some impressive outcomes for its CTE students, as well. Two-thirds of its CTE programs are known as Chapter 74–approved programs, which, among other things, makes them eligible to receive additional funds if they require their teachers to pass both a written and a performance subject matter test to get their preliminary Vocational Technical Education License. The performance test requires candidates to demonstrate skills in a hands-on setting where an evaluator assesses their tech skills and related knowledge. The programs are also required to have at least 70 percent of students eventually employed in the field of study.

The other one-third of CTE programs are dubbed “Perkins Only programs,” lacking (among other things) the funding benefit that comes from having test-based licensure. Thus, they make a handy comparison group for the researchers. Housed in both CTE-dedicated regional centers and within comprehensive high schools, Chapter 74 programs tend to enroll more White students and students with special needs than do Perkins Only programs, which tend to enroll more Black students. The study sample includes six cohorts of students with expected graduation rates from 2011 to 2016, comprising around 60,000 pupils across grades 9–12.

To address selection bias and sorting concerns, the study compares students in the same school and CTE cluster who take the same academic courses, have similar math and ELA test scores in eighth grade, and have similar demographics and school program participation. They also compare students within tracks so that they have similar course-taking patterns outside of CTE. That’s a lot of precision matching, but it’s still not a causal design.

The key finding is that, all else being equal, CTE teachers who received better scores on their subject performance test tend to have students with higher longer-term earnings than do CTE teachers who received lower scores. Specifically, a 1 standard deviation increase in teacher performance is associated with about a $900 increase in average expected earnings (approximately a 3.9 percent increase) for the teacher’s students five years after their expected graduation date, controlling for licensure test area and observable differences between students. The analysts benchmark that result against an analogous result in a seminal 2014 study that examined the impacts of teacher value-added on subsequent earnings (and other outcomes in adulthood). In that work, a 1 standard deviation increase in teacher value-added for students’ elementary teachers was associated with a 1.3 percent increase in annual earnings at age twenty-eight. Thus, CTE teacher value-added appears to function in similar ways.

The current study also suggests that the impacts are linear, such that increasing the performance of low scorers has the same impact as increasing the performance of the higher scorers. That relationship can be partly explained by the sorting that occurs into higher-paying occupations. But even then, higher scores on CTE licensure tests are independently predictive of higher earnings for students. What’s more, the scores on the performance-based, hands-on test are much more predictive of earnings than the multiple-choice, written test.

The analysts also find that teachers who are licensed in the program area in which they teach—as opposed to being licensed in a CTE cluster more generally—tend to have students with higher future earnings. But there is no relationship between CTE teacher experience (whether novices or veterans) and students’ four-year college enrollment overall. Oddly enough, there is a modest increase in the average long-run earnings of students who were five years out and had a novice CTE teacher in high school. The analysts hypothesize that, since these teachers have been more recently employed in their prior industry than veteran teachers, they may be better able to place students in a work-study position, provide current references, or make recommendations relevant in the immediate term.

Last, correlational design aside, the authors make this reasonable claim in their conclusion: “It is difficult to imagine how any licensure requirement like this could have positive impacts for students if the information collected during the licensure process did not contain any signal of teacher effectiveness.” Hear, hear! Yes, we need more rigorous research to say whether having CTE teachers with impressive, field-related licensure scores leads to high school students experiencing positive outcomes in adulthood. But for now, the signal is flashing green, so we must move ahead in identifying the most-talented teachers for this vital and growing education sector.

SOURCE: Bingjie Chen et al., “CTE teacher licensure and long-term student outcomes,” Education Finance and Policy (March 2023).

Data show that America’s current manufacturing workforce is aging and retiring as the sector is expanding exponentially and its demand for workers outpaces supply. Thus, a new report from the RAND Corporation looking at the career and technical education pathways designed to take postsecondary students directly from the classroom to the manufacturing floor is especially timely. It expands the research in this understudied area, focusing on efforts in Fordham’s home state of Ohio.

Data come from the Ohio Longitudinal Data Archive, drawing on information from the state’s higher education institutions and technical colleges, as well as from state unemployment insurance records. Student records include when each student first enrolled in a college or program; the duration of their enrollment; the program type, courses taken, and grades; whether and when the student earned a degree; and the type of degree earned. The technical college records are similar but include a course-based proxy for specific credentials earned. The data cover postsecondary enrollments and degrees earned between 2006 and 2019. The unemployment data cover 2007 through 2021, and all wage estimates are presented in 2021 dollars. To delineate “manufacturing-related” programs—the specific focus of their analysis—from other career and technical courses, the researchers use Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes. As you might imagine, the list is heavy on engineering, construction, metalwork, and plastics courses.

In 2019, more than 30,000 students were enrolled in manufacturing-related postsecondary programs in Ohio. Approximately 1,600 were enrolled in technical colleges, 13,500 in associate degree programs at traditional two- and four-year institutions, and 13,800 in bachelor’s degree programs at those institutions. Interestingly, the previous decade showed a sharp decline in the number of students pursuing associate degrees and a steady rise in the number pursuing bachelor’s degrees. Technical college enrollment remained largely flat during that time. In terms of completion, approximately 7,700 students earned a manufacturing-related credential in 2019. Not surprisingly, given the enrollment trend, the largest share earned a bachelor’s degree. The number of completers at technical colleges was down against its high point a few years earlier. That total number also includes individuals who earned a manufacturing-related certificate independent of formal higher education settings (adult apprenticeships, formal upskilling by current employers, etc.), which nearly equaled the associate degree completers. In short, Ohio’s manufacturing employers should have been swimming in applications from skilled employees.

Data show that 82 percent of those who completed a technical college program were employed within a year of completion, compared to 84 percent of those who completed a certificate, 83 percent of those who completed an associate degree, and 65 percent of those who completed a bachelor’s degree. Those percentages remained fairly strong for up to five years post-completion, indicating that degrees and credentials are valuable to their recipients. However, a much smaller share of those credentialed individuals were primarily employed in the manufacturing sector. To wit: Just 38 percent of those who completed a technical college program were employed in Ohio manufacturing at one year post-completion, compared to 27 percent of those who completed a certificate, 25 percent of those who completed and associate degree, and 30 percent of those who completed a bachelor’s degree. Those percentages also remained similar after five years.

Where were they going instead? Construction, retail, technical services, administrative/support, and waste management/remediation services were the biggest recipients of manufacturing-credentialed workers in 2019, with a perhaps-predictable differentiation in professional versus service employment based on whether workers earned bachelor’s or sub-bachelor’s degrees or credentials. The attrition does not appear to be driven by industry pay gaps, as Ohio’s manufacturing industry pays higher wages than do other industries into which credential-earning workers opt. White males are more likely than females and non-white men to move directly from credential to employment, both in manufacturing and non-manufacturing jobs, and their wages are higher, as well.

The bottom line seems to be that even with a fairly clear pathway from the graduation stage to the factory floor, Ohio needs more newly-credentialed individuals to take that step, especially if a more-diverse manufacturing workforce is desired. Unfortunately, that is easier said than done. The report suggests geographic concerns (too few manufacturing jobs in the local areas where students are graduating) and skill mismatches (credentials earned are not the ones local employers need) as prime areas where gaps could be addressed. It is to be hoped that as the Silicon Heartland takes root and expands outward from central Ohio, the new and growing manufacturing presence here will bring on a concomitant effort to reach into the education world and help shape existing training and credentialing programs to their needs, to build new ones as needed, to welcome nontraditional employees, and bridge any gaps or mismatches between school and work.

SOURCE: Lisa Abraham, Christine Mulhern, and Lucas Greer, “Strengthening the Manufacturing Workforce in Ohio,” RAND Corporation (August 2023).

Cheers

- A new Texas law encourages districts to automatically enroll students who score high enough on standardized tests into advanced math courses. —AP News

- To account for learning loss, many districts are attempting “learning acceleration,” where teachers provide grade-level work with extra support. —Education Week

Jeers

- Los Angeles could begin restricting co-location between charter and traditional public schools, causing 350 charter schools to lose access to space. —The 74

- More districts are following California’s dubious lead, watering down their math classes and incorporating instructional techniques without research backing. —The Atlantic

- Contrary to popular belief, there are actually more teachers than ever. Paired with lower student enrollment, this could lead to financial trouble. —The 74