It’s been a very busy budget season in Ohio. Issues including private school choice eligibility, charter funding, and the state’s third grade reading retention requirement have drawn the lion’s share of attention, and when the budget is finalized, these items will likely be the primary bullet points in any summary coverage. As they should be, as they’ll impact thousands of students.

But there’s an under-the-radar provision related to Academic Distress Commissions that first appeared in the Senate’s version of the budget that could also have big implications. If left untouched by the conference committee and the governor’s veto pen, this provision would dissolve the Lorain City School District’s Academic Distress Commission, as well as the district’s state-required academic improvement plan. In doing so, it would remove the district from state oversight for the first time in over a decade. This would be a major mistake.

To understand why this is a big deal, some background is needed. Academic Distress Commissions (ADCs) were first created in 2007 as a way for the state to intervene in districts that consistently failed to meet academic standards. In 2015, after failing to generate much improvement, the state strengthened the law by boosting the authority of ADCs and empowering an ADC-appointed CEO with significant managerial authority to create and implement a rigorous turnaround plan. After years of lobbying, Ohio lawmakers caved to political pressure in the summer of 2021 and created an off-ramp for the three districts under an ADC: Youngstown, Lorain, and East Cleveland. As part of the deal, each district’s board was tasked with developing an academic improvement plan containing annual and overall improvement benchmarks. If districts met a majority of these benchmarks by June 2025, their ADC would be dissolved.

Or at least that’s what was supposed to happen. The tiny budget provision introduced in the Senate dissolves Lorain’s ADC and its academic improvement plan. The district will no longer be required to demonstrate that they’re improving on behalf of their students. Their counterparts in Youngstown and East Cleveland, however, weren’t given the same free pass.

Unsurprisingly, the education establishment in Lorain is rejoicing over their special treatment. But for the rest of us, this carve-out raises some troubling questions. Why, after establishing an off-ramp during the previous budget cycle, did lawmakers suddenly decide to change course? Why did they change their minds for only one district? And what could possibly justify letting a district that’s performed so poorly for so long that it’s been under state oversight since 2013 go back to business as usual?

The only acceptable answer to any of these questions is improved student outcomes. If officials in Lorain could prove to state lawmakers that, based on reliable and comparable academic measures, their schools were rapidly and consistently improving—and if Youngstown and East Cleveland couldn’t do the same—that might justify Lorain’s special treatment.

The problem is that Lorain hasn’t had enough time to claim that its schools consistently improved. The 2022–23 school year, Lorain’s first year implementing their academic improvement plan, ended on May 31. The Senate added the Lorain ADC amendment to its budget roughly two weeks later. Could district officials have gathered enough evidence in that time to prove to lawmakers that their first year under a self-designed improvement plan had been a rousing success? Possibly. Many of the benchmarks in their plan are based on iReady and other locally-calculated measures, rather than on state exams and school report cards. That means district officials didn’t have to wait around for state test results. (Lorain’s decision to focus on local measures that aren’t easily comparable to other districts is worth pointing out.)

But even if lawmakers did consider data from the locally-calculated measures included in Lorain’s plan, and even if those results were positive (they don’t seem to be publicly available), it would still only be one year’s worth evidence. Despite what the district has tried to claim, one year of progress doesn’t prove much. To responsibly dissolve an ADC, lawmakers should need several years’ worth of data. There’s no other way to ensure that the improvements are real and sustainable, and not just a fluke. After years of underperformance, years of improvement are needed.

But what about state exam results from 2018–19, 2020–21, and 2021–22? Those data cover more than just one year. But they don’t show the kind of significant improvement that could justify letting Lorain exit state oversight early.

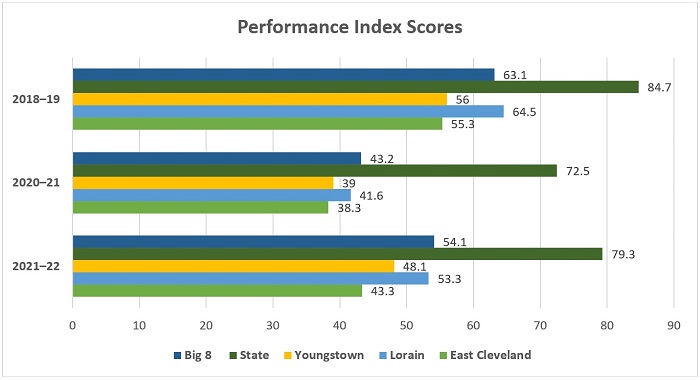

Consider the table below, which illustrates performance index scores in ADC districts, with averages from the state and the Big Eight districts included for comparison. Like its ADC and Big Eight counterparts, Lorain saw huge drops in student achievement during 2020–21. But there was also a bounce back the following year. Lorain’s performance index score for 2021–22 wasn’t just better than their prior year performance, it was better than that of Youngstown and East Cleveland, and pretty close to the Big Eight average.

Lorain deserves kudos for recovering some of that lost ground. But it’s also important to note that the district still hadn’t bounced back to pre-pandemic levels, which were troublingly and persistently low to begin with. Data from the recently finished school year, 2022–23, would go a long way toward determining whether Lorain is actually getting better, and not just recovering ground lost during the pandemic. Unfortunately, state lawmakers opted not to wait for that.

Achievement isn’t the only state report card measure that’s worthy of consideration. Ohio’s progress component, which measures the academic growth students make over the course of a year, is also crucial. It yields results that are more neutral regarding demographics, making it possible for districts where students are far behind in reading and math to showcase their contribution to student learning and reveal positive academic growth. Lorain earned a four-star rating on this component during 2021–22, which means students made more progress than expected. That’s an excellent start that the district’s teachers and students should feel great about. But it’s still just a start. Without additional years of data, lawmakers have no way of knowing whether the progress will continue.

And then there’s early literacy. For school report cards, the state tracks three measures and combines them to create an overall early-literacy rating for districts and schools. During the 2021–22 school year, Lorain earned just one star in early literacy. Only 28 percent—less than one third—of its students were proficient on the reading segment of the third grade English language arts state test. Furthermore, the district moved only 10 percent of its students from off- to on-track in reading. Given the heavy emphasis that the governor and lawmakers in both chambers placed on early literacy during this budget cycle, one would think that Lorain’s horrific performance would give state leaders pause. Sadly, that doesn’t seem to have entered the calculations.

***

We have no way of knowing why lawmakers suddenly decided to let Lorain off the hook. Given the data outlined above, it seems highly unlikely that they were wowed by sizable and sustainable academic improvements because little evidence of improvement exists. There hasn’t been enough time for Lorain to prove itself under its improvement plan.

State lawmakers have a moral obligation to ensure that students receive a quality education. Giving Lorain a pass in this way abdicates that responsibility—not because Lorain deserves to be “punished,” but because it had decades worth of poor performance in its past that has negatively impacted generations of students and the community. Easing up the pressure—as weak as it may be—will do nothing to improve student learning in Lorain.