In July 2023, Governor DeWine and the General Assembly enacted bold literacy reforms that require Ohio elementary schools to follow the Science of Reading. These practices—well supported by research—emphasize phonics, background knowledge, and vocabulary—elements that have been shown to be critical for students’ reading development. Lawmakers also allocated $169 million over the current biennium to support scientifically-based reading instruction.

Passing these provisions was a necessary first step in improving literacy achievement in the Buckeye state. Yet strong implementation—at both the state and local level—is also crucial to the success of the initiative.

This report examines one of the key implementation steps: The creation of a state-approved list of high-quality literacy curricula and instructional materials. Read the report below for the findings, or download the full report (which includes appendices).

Glossary

DEW refers to the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, formerly known as the Ohio Department of Education (ODE). This state agency implements most of Ohio’s K12 education laws.

Phonics refers to an instructional approach that involves teaching children to match sounds of spoken English with individual letters or groups of letters.[1]

Science of Reading refers to a body of research-based evidence that tells us how students learn to read, including phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics and word recognition, fluency, vocabulary, content knowledge development, and comprehension.[2] Ohio law contains a formal definition of the Science of Reading (see Appendix A.)

Three-cueing refers to an instructional approach that encourages students to rely on “cues”—e.g., a picture or the position of a word in a sentence—to read words. Three-cueing is not considered a scientifically based method of reading instruction and is often embedded in “balanced literacy” and “whole language” literacy programs.[3]

Executive summary

In January 2023, Governor Mike DeWine opened his annual state of the state address by proclaiming the “moral imperative” of providing a good education to all Ohio students. Then he turned to specifics about how to fulfill that obligation. After noting the large proportion of children struggling to read proficiently—two in five third graders—he declared a statewide goal of improving elementary-school literacy instruction:

Today, I am calling for a renewed focus on literacy—and on the way we teach reading in the state of Ohio. … Not all literacy curriculums are created equal, and sadly, many Ohio students do not have access to the most effective reading curriculum. In our budget, we are making sure that all Ohio children have access to curriculum that is aligned with the evidence-based approaches of the Science of Reading.[4]

True to his word, Governor DeWine shortly thereafter introduced sweeping literacy reforms via his budget plan (House Bill 33). These provisions, which lawmakers would approve that summer, require Ohio public schools to follow the Science of Reading starting in 2024–25. This approach to reading instruction emphasizes phonics to help students “decode” words, as well as knowledge- and vocabulary-rich content to help them comprehend what they’re reading. The bill also prohibits use of “three-cueing,” a widely used but discredited technique that prompts children to guess at words rather than sounding them out. Recognizing that extra resources were needed to transition schools successfully to the Science of Reading, lawmakers budgeted $169 million for better instructional materials, professional development, and literacy coaching.

To prepare schools for the transition, the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) recently laid the groundwork for classroom-level implementation of scientifically based reading programs. This report focuses on three important steps the agency has taken since passage of HB 33 in July 2023:[5] (1) vetting and approving a list of high-quality instructional materials from which schools may choose; (2) collecting, via statewide survey, information about the English language arts (ELA) curricula used by Ohio schools prior to the recent reforms; and (3) allocating state funds to subsidize the purchase of new curricula and materials.

We offer four key takeaways based on analyses of these activities:

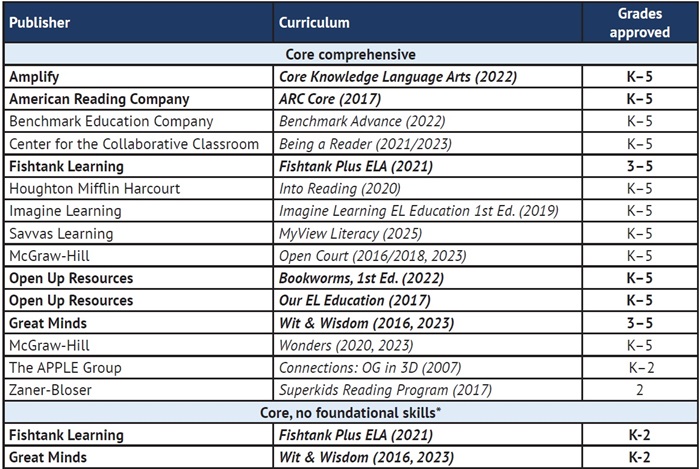

1. Ohio has wisely kept notoriously weak ELA curricula off of its state-approved list. DEW has curated an approved list of core elementary (grades K–5) curricula that includes highly respected programs such as Core Knowledge Language Arts, EL Education, and Wit & Wisdom, while excluding less effective curricula that promote three-cueing, such as Fountas & Pinnell’s Classroom and Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study. In total, DEW approved fifteen core ELA curricula for use starting next school year (the full list of approved programs, as of May 24, 2024, appears here).

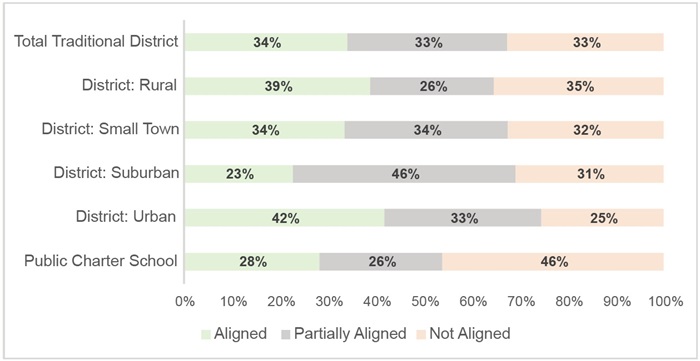

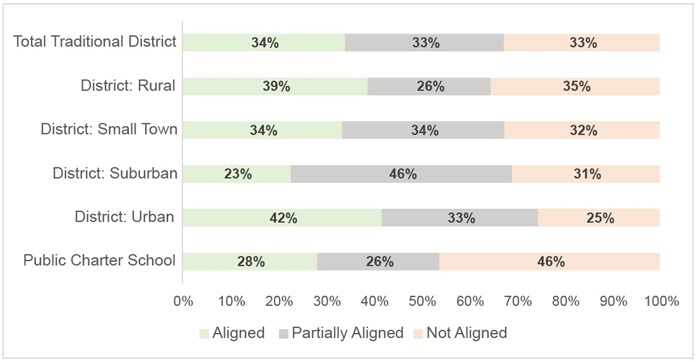

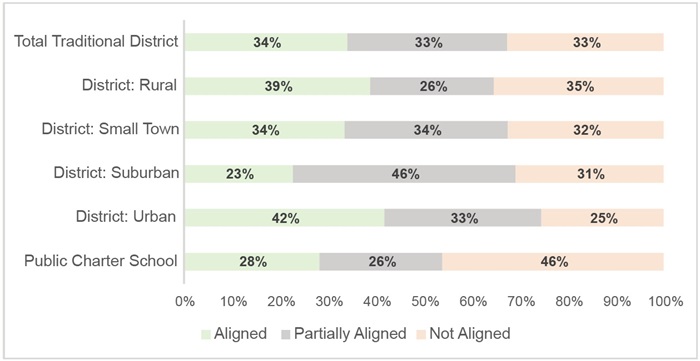

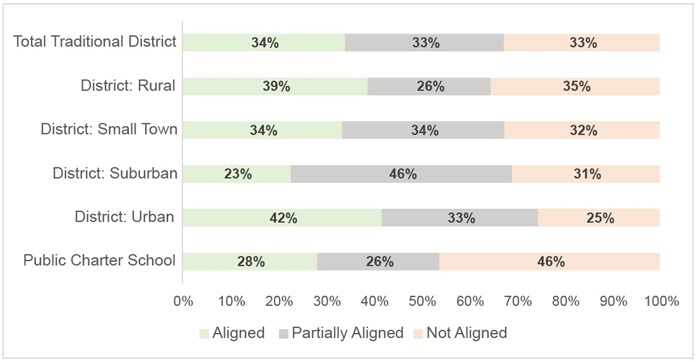

2. Just one-third of Ohio districts have been using core ELA elementary curricula fully aligned to new state requirements. Based on results from its statewide survey of curricula used in 2022–23, DEW grouped districts and charter schools into three categories: aligned, partially aligned, or not aligned to the state-approved materials list. The figure below indicates that districts statewide were evenly split among the three categories. Urban districts were more likely to have aligned curricula (42 percent), while suburban districts and charters were least likely (23 and 28 percent, respectively).

Figure ES-1: Districts and charters’ alignment (2022–23) to the state’s approved curricula list for 2024–25

Source: Ohio DEW, table titled “HQIM Subsidy Allocation Spreadsheet April 2024.” Note: DEW’s groupings are based on the ELA materials that districts and charters reported using in 2022–23 (pre-reform). The categories are as follows: aligned—used a state-approved core ELA curriculum; partially aligned—used a state-approved supplemental program (but not core); not aligned—did not use a state-approved core or supplemental program. For more on “core” and “supplemental” programs, see here; for more about the district typologies (e.g. rural or urban), see here.

Source: Ohio DEW, table titled “HQIM Subsidy Allocation Spreadsheet April 2024.” Note: DEW’s groupings are based on the ELA materials that districts and charters reported using in 2022–23 (pre-reform). The categories are as follows: aligned—used a state-approved core ELA curriculum; partially aligned—used a state-approved supplemental program (but not core); not aligned—did not use a state-approved core or supplemental program. For more on “core” and “supplemental” programs, see here; for more about the district typologies (e.g. rural or urban), see here.

Moving forward, schools with aligned ELA curricula may continue to use their existing programs, but those with partially or nonaligned programs will need to implement new ones. As discussed here, schools needing to adopt new curricula should consider those containing both solid foundational skills—e.g., phonics—and strong knowledge-building elements.

3. More than half of Ohio’s lowest-performing districts, based on third-grade reading proficiency, will be undertaking curriculum changes. When focusing on the lowest ten percent of districts as gauged by their students’ reading proficiency in third grade (n=60), the survey found that thirty-four used nonaligned or partially aligned curricula in 2022–23. Of those districts, thirteen reported using either a district-developed program or only a supplemental program, while another twenty-one used non-approved core curricula.

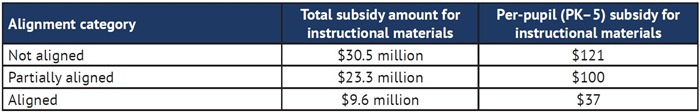

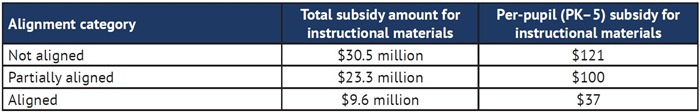

4. Districts and charter schools that previously used nonaligned curricula received more state financial support for new materials. Based on survey findings, DEW allocated most of the state’s $64 million set aside for instructional materials to districts needing to make more extensive curricula changes. Districts reporting use of nonaligned curricula in 2022–23 received on average $121 per PK–5 student[6] to purchase new materials, while those using partially aligned curricula received $101 per PK–5 student. Districts previously using approved materials—and thus not required to make substantial updates—received $37 per PK–5 student.

* * *

To its credit, Ohio is moving full speed ahead in implementing its literacy reforms. To keep the push going, the report offers five policy recommendations. In brief, they are as follows (more detail starts here):

- Maintain a high bar for inclusion on the state-approved ELA materials list. As the curriculum landscape continues to evolve, DEW should maintain a strong gatekeeping role by approving high-quality programs and keeping weak ones off the list.

- Continue state investments that support the Science of Reading. The previous state budget set aside generous sums to support the immediate needs of schools transitioning to the Science of Reading. Implementation will continue into the next biennium (FYs 2026 and 2027) and lawmakers should continue to allocate funds to sustain these efforts.

- Increase transparency about which ELA curricula districts and individual schools are using. Parents and communities should have easy access to information about the curricula used by their local schools. To this end, DEW should create a user-friendly dashboard that displays each district and school’s ELA curricula (core, supplemental, and intervention).

- Push especially hard for rigorous implementation in low-performing schools. Struggling readers stand to benefit greatly from these reforms, but that promise won’t be realized if implementation is poor. To ensure the strongest possible alignment of instruction to the Science of Reading in low-performing schools, lawmakers should require DEW to comprehensively review their literacy programs on an annual or biennial basis.

- Evaluate the impacts of the literacy-reform effort. The legislature should require studies that gauge which specific curricula and programs are most effective. Results would help support school leaders as they continue to make decisions about which materials to put into teachers’ hands, and how best to support their work in the classroom.

Under the leadership of the DeWine administration, Ohio’s literacy reforms are off and running. Now the long-term work of classroom implementation begins. If state and local leaders stay patient and resolute—keep their eye on the ball—more students will become skilled readers, will progress through the upper grades without falling behind, and will leave high school ready for their next steps.

Ohio’s ambitious literacy-reform efforts

Ohio policymakers have long understood the critical role of literacy in helping students reach their full potential. Within the past two decades, they have enacted policies aimed at lifting reading standards and increasing proficiency. For example, under former governor John Kasich, Ohio enacted the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. This legislation requires schools to annually screen students in grades K–3 for reading deficiencies and develop improvement plans for those identified as off track. Lawmakers also included a mandatory retention policy to ensure that students who fell short of a state-defined target on a third-grade reading assessment received extra time and supports.

The Guarantee has pushed Ohio schools to prioritize early intervention, and data suggest that the policy moved the achievement needle.[7] Regrettably, one component of the guarantee, the retention provision, was weakened via the most recent state budget bill (House Bill 33, enacted in July 2023).[8] Yet in that very same legislation, lawmakers gave literacy a significant boost by enacting provisions that push for more effective reading curricula and instruction. Those are issues that the Guarantee had not fully addressed but have become ripe for change, as literacy experts and advocates, often parents themselves, have pressed harder for scientifically based reading practices in elementary schools. They have rightly pointed to decades of research demonstrating the superiority of phonics-based instruction and the critical role of background knowledge for reading comprehension,[9] while also raising concerns about the continuing use of ineffective methods such as three-cueing.[10]

Ohio’s latest initiative aims to move schools toward the Science of Reading in three ways:

High-quality instructional materials: HB 33 requires DEW to establish a list of core ELA curricula and intervention programs that are “aligned with the Science of Reading and strategies for effective literacy instruction.” It further stipulates that all public schools must use materials from the state-approved list starting in 2024–25. With limited exceptions, these materials cannot include three-cueing to teach children to read.[11] DEW was also tasked with fielding a baseline survey of schools’ pre-HB 33 ELA curricula and collecting annual information about ELA curricula in future years.

Professional development (PD): To support effective implementation of new curricula, HB 33 requires educators to complete a PD course in the Science of Reading unless they’ve already completed similar training. Upon course completion, stipends of $400 or $1,200 are provided to teachers, depending on which grade and subject they teach. The course must be completed by June 30, 2025. HB 33 also calls for literacy coaches that support educators serving in the state’s lowest-performing schools as gauged by students’ reading proficiency. Roughly 100 coaches will be deployed to provide more intensive, hands-on PD for teachers in those schools.

Teacher preparation: State lawmakers also took steps to ensure that colleges of education adequately prepare prospective teachers in the Science of Reading. Per HB 33, the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) must implement an audit process that reviews preparation programs’ alignment to the Science of Reading. ODHE will begin these audits in January 2025. The bill also requires the chancellor of ODHE to revoke program approval if a review uncovers inadequate alignment to the Science of Reading and the deficiencies are not addressed within one year.

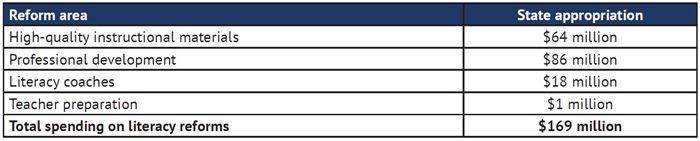

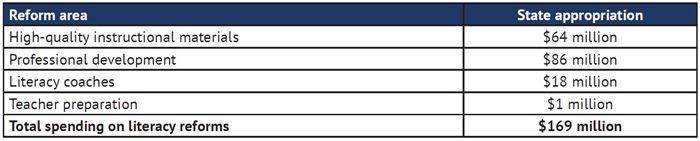

As shown in table 1, Ohio lawmakers set aside substantial funds to support these efforts. In total, the state will spend $169 million in FYs 2024 and 2025 to support the initiative, with the largest portion going toward teachers’ PD stipends ($86 million) and subsidies to purchase new curricula and materials ($64 million). Another $18 million will support literacy coaches, and $1 million is allotted to help teacher-preparation programs transition to the Science of Reading (of which $150,000 supports the ODHE audits).

Table 1: State funding set aside for literacy reforms, combined amounts for FY24 and FY25

Source: Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Analysis of Enacted Budget for the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) and the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE).

Source: Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Analysis of Enacted Budget for the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) and the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE).

While all elements of the literacy-reform package are crucial, this report focuses on the early implementation of the high-quality curricula requirement. Within the past year, DEW has completed key actions in this area, including the creation of an approved instructional materials list, release of its pre-reform curricula survey results, and the allocation of funds for instructional materials. DEW released the initial list of approved core ELA curricula and survey results on March 1, 2024. I cover the state-approved list first, as it helps interpret the survey findings. The allocation of materials funds is covered last, as it occurred several weeks later.

Identifying high-quality instructional materials

As discussed above, state lawmakers tasked DEW with creating a catalog of high-quality instructional materials that are aligned with the Science of Reading from which schools must select. Starting in 2024–25, all public schools must use “core” ELA curricula—programs designed for use in general education settings—in grades K–5 from this state-approved list. To meet this requirement, schools must use either a core comprehensive program or a coherent set of core and supplemental programs.[12] The box provides definitions that distinguish core comprehensive curricula from the hybrid—core plus supplement—option.

As discussed above, state lawmakers tasked DEW with creating a catalog of high-quality instructional materials that are aligned with the Science of Reading from which schools must select. Starting in 2024–25, all public schools must use “core” ELA curricula—programs designed for use in general education settings—in grades K–5 from this state-approved list. To meet this requirement, schools must use either a core comprehensive program or a coherent set of core and supplemental programs.[12] The box provides definitions that distinguish core comprehensive curricula from the hybrid—core plus supplement—option.

To develop state-approved lists of ELA curricula (both core and supplemental), DEW implemented a vetting process that took advantage of the widely used curricula ratings published by EdReports. Since 2015, this national, independent nonprofit has evaluated hundreds of ELA curricula to determine if they align with high-quality academic standards.[13] For each program, EdReports provides an “alignment” rating along three tiers:[14] Meets, Partially Meets, and Does Not Meet. These ratings, though sometimes debated by literacy experts,[15] often serve as an initial screening tool for states and local districts,[16] and DEW leveraged this system to approve, or not, both core and supplemental foundational skills curricula in the following way.[17]

- Top-rated Meets curricula received a streamlined review, in which the publisher attested in writing to DEW that the program aligns to the Science of Reading.[18] Curricula approved through this pathway include Core Knowledge Language Arts (grades K–5) and Wit & Wisdom (grades 3–5).

- Curricula receiving a Partially Meets rating underwent a more extensive review in which DEW examined materials and assessed their alignment with the Science of Reading. Programs approved through this process include Bookworms (K–5) and Open Court (K–5).

- Poorly rated Does Not Meet curricula were not eligible for approval. This prohibited Fountas & Pinnell’s Classroom and Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study curricula from approval, along with several others.

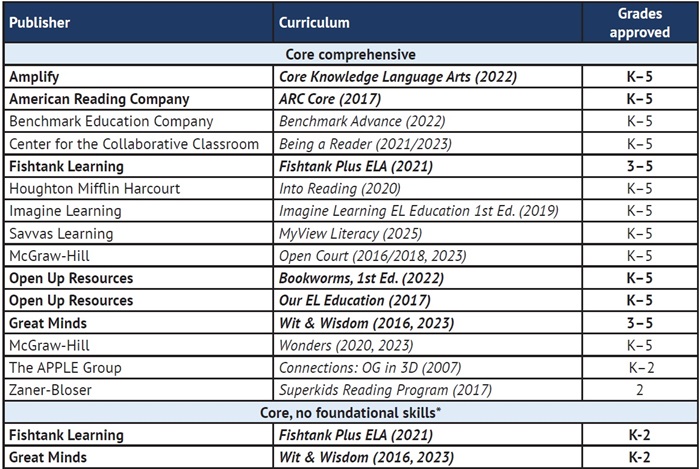

This process yielded Ohio’s list of approved ELA curricula for grades K–5. The top part of Table 2 displays fifteen approved core comprehensive curricula, while the bottom panel shows two additional grades K–2 curricula in the category of “core, no foundational skills” that were state-approved but must be paired with a supplemental program to meet the statutory requirements.

Table 2: State-approved core ELA curricula, grades K–5

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, “Approved List of Core Curriculum and Instructional Materials” (webpage, last accessed May 24, 2024). Note: (*) Districts implementing one of these programs must pair it with a state-approved supplemental foundational skills program (that list appears in Appendix B). Bold: Curricula presented in bold have been identified by the Knowledge Matters Campaign as having particularly strong knowledge-building elements (see sidebar below).

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, “Approved List of Core Curriculum and Instructional Materials” (webpage, last accessed May 24, 2024). Note: (*) Districts implementing one of these programs must pair it with a state-approved supplemental foundational skills program (that list appears in Appendix B). Bold: Curricula presented in bold have been identified by the Knowledge Matters Campaign as having particularly strong knowledge-building elements (see sidebar below).

The vetting process removed ineffective and outdated curricula—a significant step forward in a state where many schools have used inferior programs, as detailed in the next section of this report. Yet even within the state-approved curriculum list, there likely remains some variation in quality. Going beyond Ohio’s state-approved (and EdReports-driven) list are several ELA curricula that the Knowledge Matters Campaign identifies as having especially strong vocabulary- and knowledge-building elements that support reading comprehension (see the importance of knowledge-building in the sidebar below). Those programs are in bold in Table 2. Meanwhile, though meeting Ohio’s baseline requirements, some literacy experts have questioned whether several of the non-bolded curricula—sometimes called “basal readers”—are too light on knowledge-building.[19] Nevertheless, despite ongoing discussion about what precisely constitutes a high-quality curriculum, DEW has given its stamp of approval to a relatively small number of core ELA programs, especially in light of the dozens of curricula options available.

Schools’ prereform curricula, and financial support for change

Ohio has not historically required schools to report their curricula publicly, so there’s not been much information about which programs schools have been using. Seeking a systemwide picture of existing literacy curricula, state lawmakers in HB 33 directed DEW to gather information via a statewide survey. In September 2023, DEW fielded the survey, which garnered near-universal response rates (99 percent of districts and charters). Schools were asked about the core ELA curricula (grades K–5) and intervention programs (grades K–12) that they used in 2022–23, just prior to enactment of the state’s literacy reforms. The department released results in spring 2024.[24]

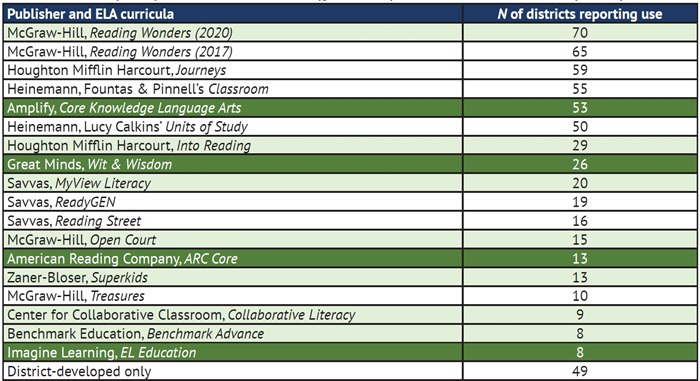

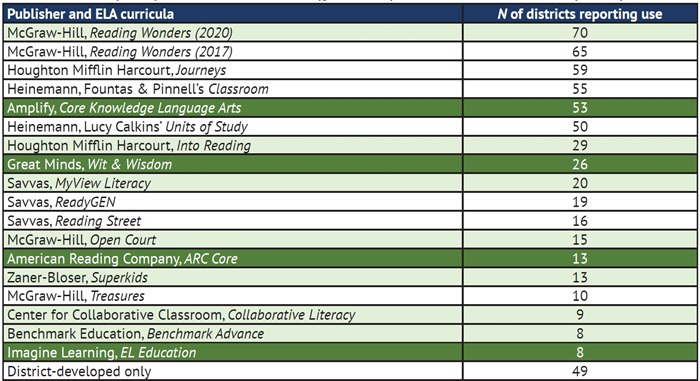

Table 3 displays the most commonly used core ELA elementary programs among traditional school districts. We see a wide range of curricula in use as well as variation in their quality, as indicated by whether DEW has since approved the program and whether the Knowledge Matters Campaign has recommended it. The survey also revealed widespread use of ineffective and nonapproved curricula such as Classroom and Units of Study (they were the fourth and sixth most frequently cited programs). Other nonapproved curricula such as the 2017 edition of Reading Wonders[25] and Journeys were also common. At the bottom of the table, we see that another forty-nine districts reported use of only a district-developed program. (Under the new legislation, they will need to adopt an approved curriculum.)

More positively, we find signs that some districts have been using high-quality programs. The most-used core ELA program was the state-approved 2020 edition of Reading Wonders. The most common programs that are both state-approved and Knowledge Matters-recommended were Core Knowledge Language Arts and Wit & Wisdom. Districts using approved curricula in 2022–23 will be able to continue their use of these programs.

Table 3: Most frequently used core ELA curricula (grades K-5) in 2022–23, Ohio districts (n=604)

Source: Author’s analysis of DEW survey question regarding districts’ core (aka, “tier 1”) ELA curricula for grades K–5. Notes: This table includes any core curricula that were reported by five or more districts; it excludes supplemental or intervention materials that districts reported in response to the “Tier 1” survey question. Districts could report use of multiple core curricula, and many did so. The vast majority of districts reported curricula at the district level, not for individual schools.

Source: Author’s analysis of DEW survey question regarding districts’ core (aka, “tier 1”) ELA curricula for grades K–5. Notes: This table includes any core curricula that were reported by five or more districts; it excludes supplemental or intervention materials that districts reported in response to the “Tier 1” survey question. Districts could report use of multiple core curricula, and many did so. The vast majority of districts reported curricula at the district level, not for individual schools.

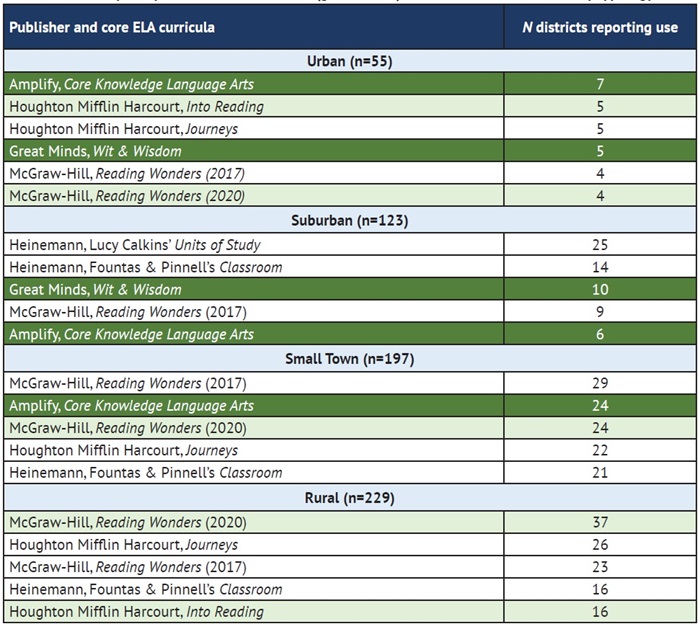

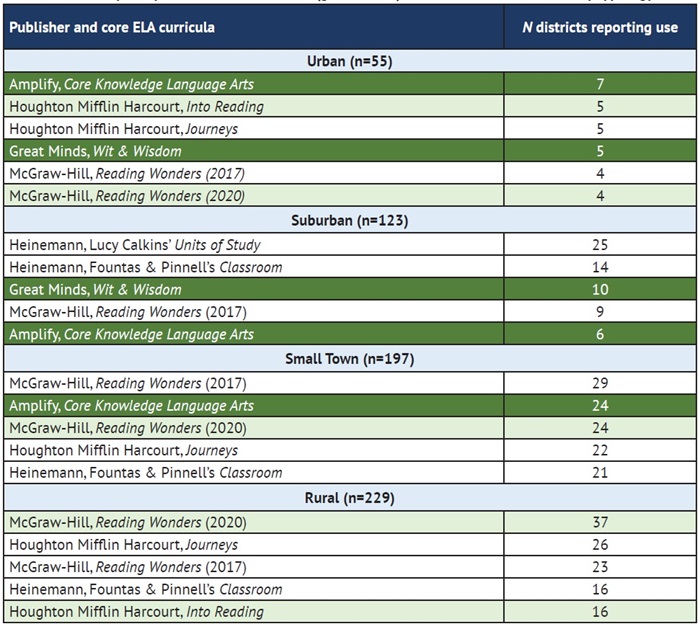

Table 4 displays patterns by district typology, a way of grouping schools based on their geographic characteristics. It shows that urban districts were more likely to have implemented state-approved programs prior to the legislative reforms. Suburban districts, on the other hand, were more likely to cite use of nonapproved curricula, notably Units of Study and Classroom. Rural and small-town districts reported significant use of Reading Wonders (2017 and 2020 editions), which helps explain their appearance atop the statewide list in Table 3, as more districts are represented in those typologies.

Table 4: Most frequently used core ELA curricula (grades K–5) in 2022–23, Ohio districts by typology

Note: This table displays the five most frequently reported core ELA curricula by DEW’s district typologies.

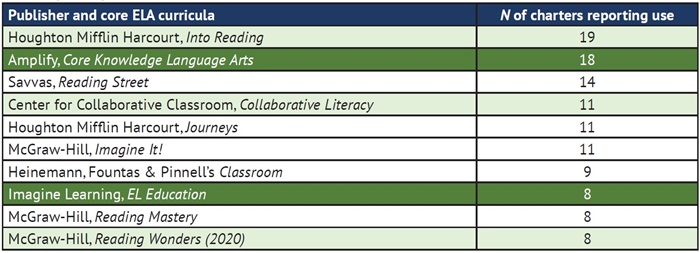

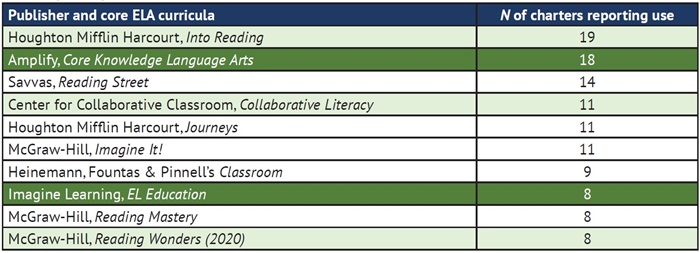

Note: This table displays the five most frequently reported core ELA curricula by DEW’s district typologies.The next table displays public charter schools’ most commonly used curricula. We again see a range of programs in use, with some less-frequently cited curricula among districts being more common among charters (e.g., Imagine It! and Reading Mastery). Two state-approved programs, Into Reading and Core Knowledge Language Arts, were the two most widely used by charters in 2022–23.

Table 5: Most frequently used core ELA curricula (grades K-5) in 2022–23, Ohio public charter elementary schools (n=222)

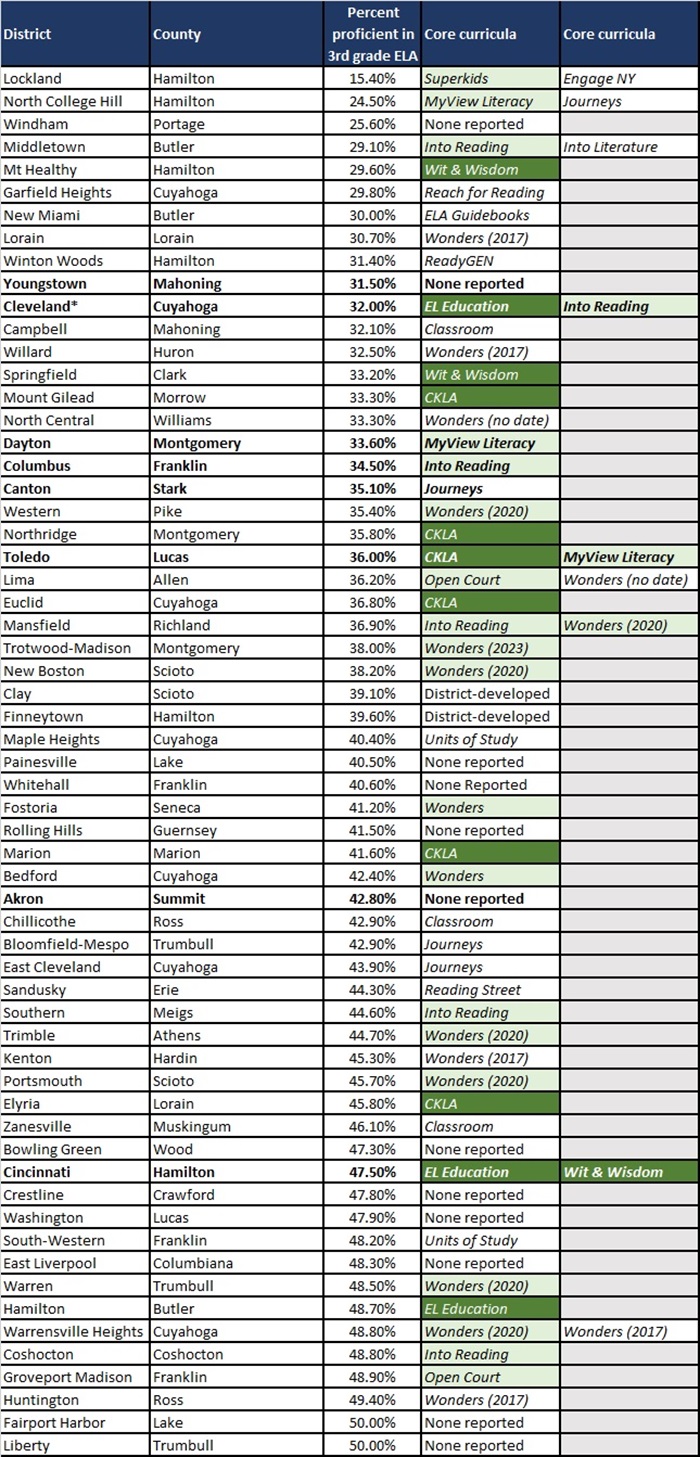

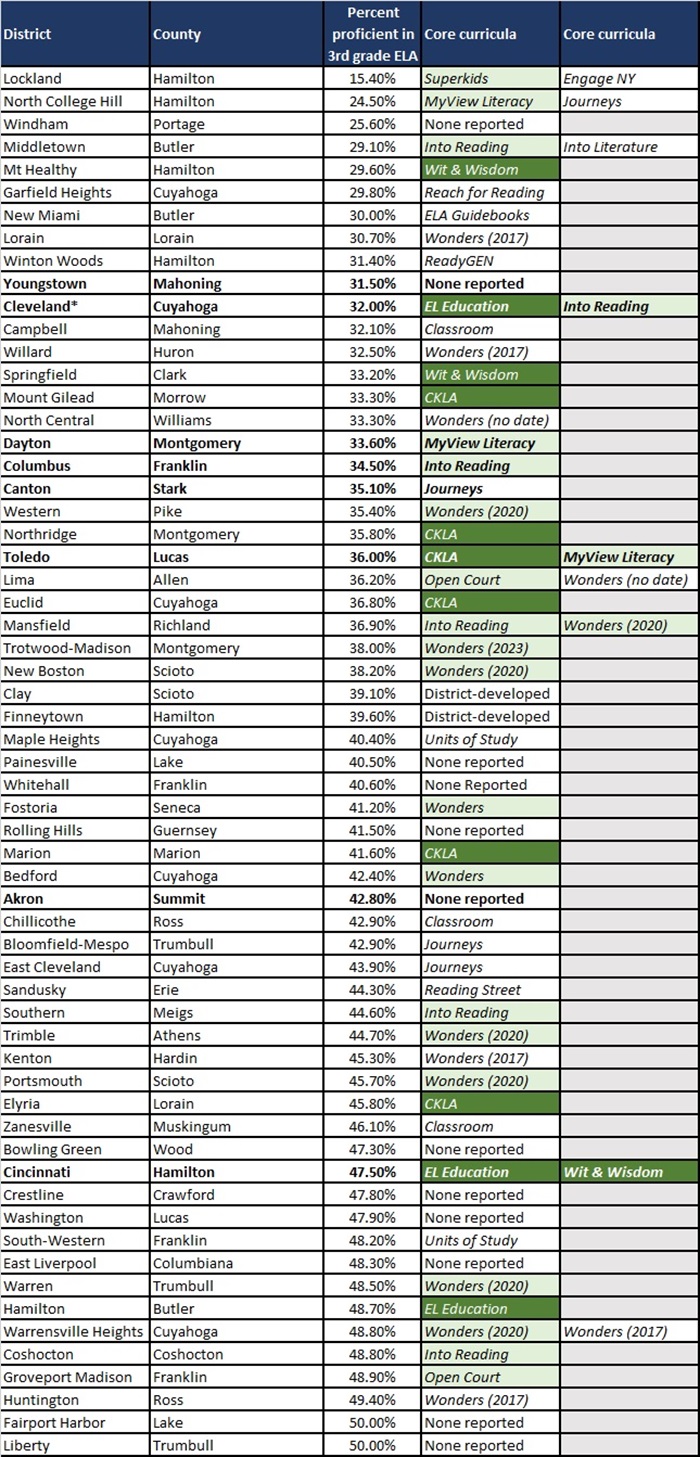

While all students will gain from the use of more effective ELA curricula, those struggling to read stand to benefit most. Table 6 displays the specific programs used by the districts with the lowest third-grade ELA proficiency rates in 2022–23. (The “Ohio Eight” urban districts are in bold.) Thirty of these sixty districts reported use of a state-approved core ELA curricula and eleven of them reported the use of a program that’s also recommended by the Knowledge Matters Campaign. The other half used non-approved published curricula, district-developed curricula, or did not report a core ELA curriculum on the survey.[26] As discussed in Appendix C, low-performing districts using a state-approved curriculum seem to slightly outperform those using nonapproved curricula on the state’s value-added growth measure. But for reasons discussed in that section, this conclusion is tentative, and further research is needed to rigorously evaluate the impacts of curricula decisions, both statewide and in struggling schools.

Table 6: Core ELA curricula (grades K–5) used in 2022–23 among the lowest 10 percent of Ohio districts in third-grade reading proficiency

Notes: This list includes districts in the lowest 10 percent of districts statewide as gauged by their students’ third-grade ELA proficiency in 2022–23; the Ohio Eight big-city districts appear in bold. CKLA = Core Knowledge Language Arts. Wonders (no date) indicates a district “wrote in” the program in response to the survey item but did not provide a publication year. (*) Cleveland is the only district on this table that reported more than two core ELA curricula. It was one of just a few districts that reported school-level curricula; EL Education was used in the majority of its buildings.

Notes: This list includes districts in the lowest 10 percent of districts statewide as gauged by their students’ third-grade ELA proficiency in 2022–23; the Ohio Eight big-city districts appear in bold. CKLA = Core Knowledge Language Arts. Wonders (no date) indicates a district “wrote in” the program in response to the survey item but did not provide a publication year. (*) Cleveland is the only district on this table that reported more than two core ELA curricula. It was one of just a few districts that reported school-level curricula; EL Education was used in the majority of its buildings.

Survey results confirm both the heavy lift the state is undertaking to transition schools away from weaker curricula and the wisdom of investing significant dollars to support new ELA programs. As noted earlier, one of the largest funding elements for the initiative is $64 million to subsidize the purchase of instructional materials. For the purposes of allocating funds to districts and charter schools, DEW divided them into three categories based on their survey responses about which programs they used in 2022–23. The categories are as follows:

- Aligned: Reported use of a state-approved core ELA curricula.[27]

- Partially aligned: Reported use of only a state-approved supplemental foundational skills program.

- Not aligned: Did not report use of a state-approved core or supplemental program.

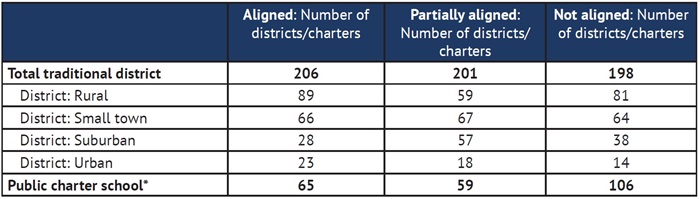

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of districts and charters by these three categories. Statewide, districts were split evenly among the three categories, with urban districts—perhaps sensing a greater urgency to upgrade curricula—being more likely to be in the aligned category (39 percent), while suburban districts and charters were less likely to be aligned (23 and 28 percent, respectively). Table 7 displays the corresponding number of districts and charters in each of the categories.

Figure 1: District and charters’ alignment (2022–23) to the state’s approved curricula list for 2024–25

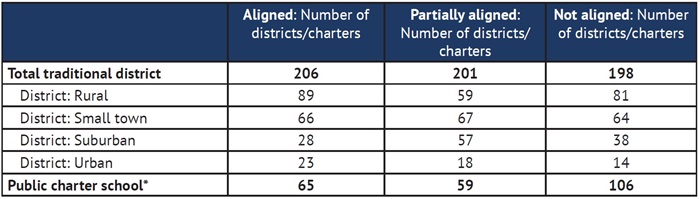

Table 7: Number of districts and charters by their alignment (2022–23) to the state’s approved curricula list for 2024–25

Source: Ohio DEW, table titled “HQIM Subsidy Allocation Spreadsheet April 2024.” Note: (*) This count includes one independent STEM school that serves elementary grades.

Source: Ohio DEW, table titled “HQIM Subsidy Allocation Spreadsheet April 2024.” Note: (*) This count includes one independent STEM school that serves elementary grades.

Based on this grouping methodology, DEW then steered more dollars to nonaligned schools. Table 8 shows that nonaligned districts and charter schools received just under half of the total allocation—$31 million of the $64 million set aside—while those deemed partially aligned and aligned received $23 and $10 million, respectively. On a per-pupil basis (grades PK–5), these sums amount to $121, $100, and $37 for nonaligned, partially aligned, and aligned districts and charters, respectively. Dollars must be used to purchase state-approved instructional materials,[28] whether core ELA curricula, supplemental materials, or intervention programs.

Table 8: Funding allocations to districts and charter schools for instructional materials, by alignment category

Note: A small sum ($0.5 million) was distributed to joint vocational districts, charter schools, and STEM schools that do not serve students in grades K–5. They received funds to support the purchase of intervention materials in the upper grades.

Note: A small sum ($0.5 million) was distributed to joint vocational districts, charter schools, and STEM schools that do not serve students in grades K–5. They received funds to support the purchase of intervention materials in the upper grades.

Conclusion and recommendations

With literacy reforms solidly on the books and implementation off the ground, Ohio is moving smartly toward more effective reading instruction. But to achieve the intended results of the initiative—higher reading proficiency statewide—Ohio policymakers will need to keep the pedal to the floor, while also exercising patience and resolve when the going gets tough. They must keep in mind that transitioning hundreds of schools to new curricula and instructional practices won’t happen overnight. As literacy expert Robert Pondiscio has noted, learning to read “is the long game,” requiring time and persistence from both teachers and students.[29] To maintain a strong and sustained push toward better literacy instruction, we conclude with five recommendations for Ohio leaders:

With literacy reforms solidly on the books and implementation off the ground, Ohio is moving smartly toward more effective reading instruction. But to achieve the intended results of the initiative—higher reading proficiency statewide—Ohio policymakers will need to keep the pedal to the floor, while also exercising patience and resolve when the going gets tough. They must keep in mind that transitioning hundreds of schools to new curricula and instructional practices won’t happen overnight. As literacy expert Robert Pondiscio has noted, learning to read “is the long game,” requiring time and persistence from both teachers and students.[29] To maintain a strong and sustained push toward better literacy instruction, we conclude with five recommendations for Ohio leaders:

- Maintain a high bar for inclusion on the state-approved ELA materials list. Publishers will inevitably update existing curricula and bring new programs to market. Some will be high-quality and adhere to the Science of Reading, while others will not be as strong. As the curriculum landscape evolves, DEW should maintain a strong gatekeeping role and approve only high-quality materials. In future review cycles, the agency should take into account any new evidence about the effectiveness of specific programs as well as developments in third-party curricula reviews, including at EdReports.[30]

- Continue state investments that support the Science of Reading. Implementation that yields results for students will require time, commitment, and resources. To their credit, lawmakers made a significant down payment on these literacy reforms in the previous biennial budget. The next General Assembly should follow their lead and preserve set-asides for literacy in the upcoming state budget. While the precise uses of dollars should evolve to match the changing needs of schools, additional investments in professional development, literacy coaching, and high-quality materials can help solidify and sustain implementation.[31]

- Increase transparency about which ELA curricula districts and individual schools are using. In addition to the baseline survey of curricula described in this report, state lawmakers directed DEW to collect annual information about ELA curricula moving forward. Yet they did not explicitly require the agency to report this information publicly. In the coming years, DEW should make this information available to the public in a user-friendly format. Akin to Colorado’s “curriculum transparency dashboard,”[32] Ohio should create a centralized site that displays core, supplemental, and intervention programs used by each school. Information at an individual building level is important for parents seeking to understand their local schools’ curricula (which could vary within a larger district).

- Push especially hard for rigorous implementation in low-performing schools. To ensure that struggling readers receive the best possible instruction, state leaders should press for rigorous implementation of high-quality core instruction and interventions in the lowest-performing schools. In addition to maintaining extra support for teachers via literacy coaches, DEW should also begin to conduct, with the support of literacy experts, on-site reviews of the literacy programs in low-performing elementary schools.[33] These more in-depth reviews would go beyond basic compliance checks and also gauge the quality of implementation, provide feedback and suggestions for improvement, and identify additional supports that may be needed.

- Evaluate the impacts of the literacy-reform effort. As implementation moves forward, research will be critical to identify strengths and weaknesses. State policymakers should commission studies that examine success of the reform package as a whole as well as various aspects of it, such as which specific state-approved curricula are most effective and what types of teacher PD provide the biggest boost. Analyses like these would support school leaders as they continue to make decisions about which materials to put into teachers’ hands and how best to support instruction. They would also help guide state leaders as they steer the initiative forward.

Literacy is job number one for Ohio’s elementary schools. State leaders are right to insist that all classroom teachers have the curricula, materials, and training needed to do the job right. A wealth of evidence demonstrates that programs aligned with the Science of Reading are most effective at helping children become strong readers—the more so when those programs are also rich in knowledge. With strong implementation in the years ahead, Ohio will have more proficient readers in schools today and a more literate citizenry tomorrow.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my Fordham Institute colleagues Michael J. Petrilli, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Chad L. Aldis, Jessica Poiner, and Jeff Murray for their thoughtful feedback during the drafting process. Special thanks to Kathi Kizirnis, who copy edited the manuscript, and Andy Kittles who created the design. Funding for this report comes from the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies and our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation.

— Aaron Churchill

Ohio Research Director, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute promotes educational excellence for every child in America via quality research, analysis, and commentary, as well as advocacy and charter school authorizing in Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, and this publication is a joint project of the Foundation and the Institute. The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University.

Endnotes

[5] Teacher professional development, literacy coaching, and teacher-preparation reform are also crucial elements of the overall literacy reform package and will be reviewed in future analyses.

[6] Though not the focus of this report, the state will also require district- or charter-operated preschools to use state-approved reading curricula; this is why the amounts are reported on a PK–5 enrollment basis.

[11] Three-cueing may be allowed if it appears in a special-education student’s IEP, or if DEW approves a school’s request to use three-cueing with a particular student (provided he or she is not on a reading improvement plan).

[14] For core ELA programs that achieve a Meets “alignment” rating, EdReports also includes a “usability” rating. DEW, however, relied strictly on the “alignment” ratings to develop its approved materials list. For more about its ratings and review process, see EdReports, “Our Process” (webpage, last accessed May 21, 2024): https://edreports.org/process#intro.

[17] Provided it receives a satisfactory review from by another state, a curriculum not rated by EdReports could apply for DEW approval as well. Description of the review process and rubric is available at Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, High-Quality Instructional Materials in English Language Arts: PreK-Grade 5 Core Curriculum and Instructional Materials Approved List: Vendor Guidance and Request for Applications (2023-24): https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Englis….

[18] If a core, no-foundational-skills curricula had a Meets rating, it was automatically approved by DEW. There were two such programs that met this criterion (Wit & Wisdom, grades K-2, and Fishtank ELA, grades K-2).

[25] Wonders was one of only a few curricula for which DEW reported a particular publication year.

[26] The districts marked as “none reported” reported only supplemental or intervention materials in the survey question about core ELA curricula.

[27] This could either be a core comprehensive or a combination of state-approved core, no foundational skills curricula and state-approved supplemental foundational skills curricula.

[28] A district or charter school may apply these funds to a previous purchase of state-approved curricula, provided it occurred after July 1, 2023.

[33] Such schools could be those that have been assigned a literacy coach (they serve in the lowest-performing schools in statewide proficiency in ELA), or elementary schools that are formally identified for “comprehensive support and improvement” under federal law.