- A solid program for advanced education should focus on both acceleration and enrichment. —Education Week

- In the aggregate, “gifted” individuals tend to live lives just like everyone else. —David Brooks, New York Times

With a 3-2 vote last week, the Upper Arlington school board signed onto a lawsuit that aims to strike down Ohio’s EdChoice scholarship program. First enacted in 2005, EdChoice today provides financial assistance to roughly 130,000 students to defray, or fully cover, the cost of private school attendance. Historically, scholarship eligibility has generally been limited to lower-income families, but legislators in recent years have allowed more parents to access the program. Legislation passed just last year made all Ohio families eligible for scholarships, with wealthier families eligible for partial scholarships.

The expansion of EdChoice has riled up the public-school establishment, which perceives the program as a threat to its longstanding hegemony over K–12 education. To protect their interests, choice opponents have (in addition to litigation) embarked on a PR campaign aimed at bashing private schools. The “Vouchers Hurt Ohio” group, which receives support from more than 100 school districts, accuses private schools of “siphoning” money from public schools, a claim that flies in the face of empirical evidence showing EdChoice has no impact on districts’ per-pupil expenditures. The group also attacks the program for creating a “system of state-funded discrimination,” even though private schools must follow non-discrimination policies and have served countless low-income, Black, and Hispanic students through the years.

If all this melodramatic rhetoric weren’t enough, now we get this: One of the state’s wealthiest school districts is trying to strip educational choices from less advantaged families by joining the lawsuit.

Serving a posh enclave just outside of Columbus, Upper Arlington had the fourth highest median resident income and the forty-ninth highest property valuation per pupil of Ohio’s 608 school districts in 2022–23. Its average teacher salary ($91,306) ranked fifth highest statewide and the district spent $17,677 per pupil, 15 percent above the statewide average. This spending figure excludes capital outlay, so it wouldn’t even reflect the district’s recently completed, $235 million school facilities upgrade.

I’ve got no quarrel with residents in affluent communities using their own resources to generously support public schools. Decades ago, I benefitted from attending a well-off school district that provided a good education. What’s unfathomable is when districts like Upper Arlington use their power and prestige to harm families who are less fortunate.

Let us recall that this year alone, some 27,500 Black and Hispanic students received an EdChoice scholarship. If EdChoice goes away, children from poor families and distressed neighborhoods in cities like Columbus will be forced to trek back to an “assigned” public school that may be unsafe or provide a substandard education. Without EdChoice, working-class families from all across the state will need to make much tougher decisions about whether they can afford a private school for their sons and daughters.

Most of the district leaders and residents of Upper Arlington are fortunate not to have to make those types of agonizing decisions for their children. Their well-resourced public schools work for the vast majority of students, and the state’s scholarship program—even an expanded one—has a next-to-nil impact on the district. Why advocate to snatch educational opportunities from the hands of disadvantaged Ohio families? Why heap scorn on the private schools that serve some of the state’s neediest students—something that wealthy districts like Upper Arlington refuse to do by forbidding open enrollment?

Perhaps the Upper Arlington school board didn’t fully understand the ramifications of their actions. Maybe they got caught up in the political theater. Whatever the case may be, the result was a shameful, sickening display of elite power and privilege.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- Yet more voucher grouching in the Statehouse News to start the day today. This time, their tale of woe is how sad it is for rural families to know there’s a voucher program but no (or not many, or none with lots of open seats) private schools in the area for them to access. Seriously? You guys are actually mad that a handful of kids

are still stuck with only the traditional districtmight not be able to access a voucher? Surely you jest. (Statehouse News Bureau, 6/18/24) While the quoted grouchers may or may not be jesting about those specific deeply-held concerns, you might have noticed that the documented possibility of a concern by itself is nonetheless presented in that piece as reason enough for the state to just voluntarily cancel the entire voucher program (“Oops, we didn’t realize!”)—so as to eliminate the fully-documented potential (just ask them) for the sadness of those clearly deprived and downtrodden rural folks. But just in case that oh-so-logical outcome doesn’t actually happen based on the clearly-documented, fully-understandable concerns of possible harm, there are still other means by which to blow the whole thing up. Like in this other Statehouse News piece (anyone besides me sensing a theme this week?), where the future of the voucher program is unequivocally reported to be “uncertain” due to the pending voucher groucher lawsuit. I’m sure that this authoritative declaration, fully journalistically supported by the solid facts contained in the piece (just ask them), will deter tens of interested parents from pursuing an EdChoice Scholarship, even on the off chance that it doesn’t end up being struck down in court several months after the start of the next school year. (Statehouse News Bureau, 6/19/24) - Speaking of those dastardly religious private schools (they were; not me), here’s a great story about Cornerstone Christian Academy in northeast Ohio. Not only has CCA been supporting area homeschooled students’ academic needs for years, they will soon be sharing the benefits of an Ohio Department of Education and Workforce grant with those families as well. That is, throwing open the doors of their new, state-of-the-art STEM lab for a program to actually allow homeschoolers to learn the skills needed to earn numerous industry certifications. How very

dastardlyneighborly of them. (The News-Herald, 6/17/24) - And speaking of wasting public money on private education expenses (again, that was them; not me), here’s some good news for families who received but have not yet spent down their Afterschool Child Enrichment dough: More time to use their remaining funds. (Richland Source, 6/18/24) The previous clip is basically just the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce’s press release, which is nice and easily accessible without a subscription. But if you’d like the more solemn journalistic version of the story with a potted history of the program and more, you can use one of your limited free articles to read about it here. (Cleveland.com, 6/19/24)

- Finally today, we learn that the new K-5 expansion of the Dayton Regional STEM School is on an “accelerated timeline” for completion. Which just so happens to be my favorite kind of timeline for news like this. Awesome! (Dayton Daily News, 6/18/24)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

“The Big Bang Theory” premiered September 2007. My husband has a nuclear engineering degree from MIT. Our younger son, then four, was a budding scientist. (Sample conversation: Him: Can’t come out of the bath. Working on surface tension and light refraction. Me: You mean splashing?)

We tuned in to the pilot. We liked it well enough to keep watching. However, as inevitably happens with Chuck Lorre shows, the humor quickly became mean-spirited, the characters nasty, the plots cliched.

When “Young Sheldon” debuted ten years later, though, it seemed different enough in spirit that we gave it a shot.

By that time, we had a fourteen-year-old son who’d been begging us to let him drop out of school since third grade. He said he was bored. He said he wasn’t learning anything. He said he could do a better job educating himself.

We struck a deal. He would stay in school, behave himself in class, and, once he graduated 8th grade, he could go straight to college.

There were definitely ups and downs over the intervening five years. Instances like his teacher calling to report he got an uncharacteristic D on a geography test. “I don’t think it’s a learning issue,” the teacher began.

“Oh, it’s a learning issue,” I snapped. “He didn’t learn the material.”

My son informed me he didn’t study for the test because he found geography pointless. I informed him that this wasn’t keeping with our bargain.

There were also report cards with the note: His need to question everything the teacher says can become tiresome.

A sample exchange:

Teacher: Think of “is” as an equal sign.

Him: No. Because if you say, “A rose is red,” then the color red is an aspect of the rose, but if you say, “Red is a rose,” a rose is not an aspect of the color red.

He managed to graduate eighth grade. He’d kept his promise. I was determined to keep mine.

We agreed one of New York’s city colleges would be fine. But, as it turned out, CUNY won’t let applicants take its placement test without a high school diploma. Over 50 percent of teens who graduate NYC high schools with a diploma can’t pass the CUNY placement test—but passing the placement test won’t get you a high school diploma!

With the plan for him to attend an affordable school and live at home proving impossible, we adjusted our parameters and visited Simon’s Rock, an early college in Massachusetts. Though it was by no stretch of the imagination affordable, it claimed to meet all financial need via scholarships.

To make the day trip happen, my husband and I took off work. Because neither of us drive, my brother volunteered to chauffeur us, which required him taking time off work, too. I arranged for my daughter to go to a friend’s house after school and for my oldest son to pick her up from there in the evening.

While none of us were impressed with Simon’s Rock’s academics, we still allowed our son to apply. He was ecstatic to get in. Then came the price tag. They wanted four times what we were paying for our oldest to attend an Ivy League university. So much for “meeting all financial need.”

My son was devastated. He was furious. He was belligerent.

Seeing him so upset, I was severely tempted to find some way for him to go. We’d borrow the money.

This is where “Young Sheldon” came in. That show’s narrative never matched “The Big Bang Theory’s.” Adult Sheldon maintained no one in his family understood his genius or supported him.

Yet, in seven seasons of the spin-off, we watched Sheldon’s mother, father, and grandmother go out of their way to drive him to his university classes. His dad flew with him to Caltech. His mom went with him to Germany. Sheldon was incredibly supported by his family—which he never appreciated.

What stopped me from giving in to my son over early college was watching Mary perennially giving in to Sheldon—and the entitled, self-absorbed monster that turned him into. One who didn’t even notice the sacrifices other people were making for him, because he simply accepted it as his rightful due.

So we told our son he’d be attending Stuyvesant, NYC’s top public high school. At the end of freshman year, he asked again to be allowed to drop out.

We didn’t let him.

The reasons were, once again, connected to “Young Sheldon.” I didn’t want to give my son the sense he was better than the people around him. Stuyvesant is a school for NYC’s highest performing students. If it was good enough for them, it was good enough for him (and his father and his brother, too). The last thing I wanted was a boy who, like young Sheldon, thinks he’s smarter than everyone around him and that this gives him license to belittle them. A kid like that grows into an adult who mocks his friend for “only” having a master’s degree (even though said friend is also an astronaut) and dismisses entire areas of study, like geology, as not real science.

So my son returned for sophomore year. And then the pandemic hit. Now when he said he wasn’t learning anything and showed the level of work that was being asked of him, I was forced to agree.

So could he drop out and educate himself now?

Yes. But on one condition. Again, thanks to “Young Sheldon.”

I told my son he could drop out and homeschool himself. But he would do all the work himself. He would research homeschooling law himself, and file the paperwork himself, and select his classes himself, and arrange to take his Advanced Placement tests (and, later, his high school equivalency) himself. I would not lift a finger to help.

This was because, on “Young Sheldon,” I saw what happened when a mother put one child’s needs above all others.

I watched Missy explain that while her dad and older brother Georgie have football in common, and her mom and Meemaw are always “fussing over Sheldon,” Missy is left on her own. I seethed when, during a trip to Houston so Sheldon could debate math with a NASA scientist, Missy’s pleas to stop at an ostrich farm are ignored. And I was driven to tears as Missy’s cries for attention, to the point of running away from home, are dismissed and punished, while Sheldon’s horrible behavior is excused and even rewarded.

That wasn’t going to happen at my house. Thanks to “Young Sheldon,” I went out of my way to make sure it wasn’t only my son’s triumphs which were celebrated. I insisted he attend his sister’s gymnastics meets and, when she competed internationally, that we watch the livestream of her opening ceremony. (Did we see her in the throng of thousands? No, we did not. But that wasn’t the point.) Her accomplishments were no less valuable than his.

Last month, Jonathan Plucker wrote about the sitcom “‘Young Sheldon’ provides insight into parenting bright children.” I couldn’t agree more. But for me, the show proved a blueprint for everything not to do.

I didn’t want a son who acted like young Sheldon Cooper. I most certainly didn’t want one who grew up to behave like adult Sheldon. Even in the last episode, Jim Parsons’s cameo demonstrated that Sheldon still spoke condescendingly to his wife, had no interest in supporting his children’s passions, and mocked people whom he called his friends.

If looking at everything Mary Cooper did when raising Sheldon and doing the opposite was what it took for me to raise the anti-Sheldon, then so be it.

But how could I argue with Sheldon’s success, some might ask? He went to Caltech! Doesn’t that make putting up with his abhorrent personality worth it?

If that’s what we’re using as a metric, then my son also got into Caltech—but chose to go elsewhere. There’s definitely more than one way to parent a bright child. I chose to go the anti-“Young Sheldon” route.

Editor’s note: This was first published by Education Next.

What are the best ways to deploy finite resources for the betterment of young children? What inputs provide the most beneficial outcomes later in life? These are big, important questions whose answers matter to individuals, families, and society. A new report from Urban Institute’s Income and Benefits Policy Center aims to provide the answers.

Authors Kevin Werner, Gregory Acs, and Kristin Blagg build on a large body of previous research showing the well-established link between childhood and adult outcomes. They add to the literature by constructing a model that simulates changes in several variables at different points in children’s lives and projecting their outcomes as adults. Data come from the Social Genome Model (SGM), a microsimulation model of the life cycle that tracks the academic, social, and economic experiences of individuals from birth through middle age in order to identify the most important paths to upward mobility. They translate SGM data to match real world data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey-Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) for childhood outcomes at ages five, eight, and eleven, and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 Cohort (NLSY97) for adult outcome data.

Their model focuses on a single adult outcome: earnings at age thirty. While this is mainly because age thirty is currently the extent of the SGM data, they also consider earnings a useful proxy measure for other aspects of adult life, “given the strong relationship between higher income and other indicators of well-being, such as physical and mental health.” Additionally, research has shown that earnings at age thirty are predictive of lifetime earnings.

They look at sixteen different factors across four different stages of childhood: birth, preschool, early elementary school, and middle childhood. The model contains variables from five different domains for each life stage, comprising cognitive and academic development, emotional and psychological development, physical health and safety, mental health, and social behaviors. The changes their model introduce to childhood circumstances are all improvements, and all important. Examples include increasing birth weight to safer levels, boosting math and reading test scores by 0.5 standard deviations, and improving health indices by 0.5 standard deviations. Changes are introduced at various points in childhood to determine their adulthood impact.

Findings indicate that improving children’s math scores outshines all other factors and increases adult earnings the most. Improving preschool (age five) math scores by 0.5 of a standard deviation yields an impressive 2.5 percent increase in earnings at age thirty; doing so in middle childhood (age eleven) raises earnings by 3.5 percent, which corresponds to about $1,200 per year (in 2018 dollars) in additional earnings for the average adult. Roughly similar impacts are seen in children of all races and ethnicities across life stages, with Hispanic children consistently seeing the largest gains. Girls tend to see a higher earnings boost than boys. By comparison, improvements in childhood health indices result in small but steady earnings increases of 0.6 to 0.7 percent in adulthood, with larger gains for Black and Hispanic children as compared to their White peers. Improvements in reading test scores (again, 0.5 of a standard deviation) give a nearly 1 percent bump to adult earnings when they happen at age five, but decline by half when they occur at age eleven.

The authors do not discuss potential mechanisms at work, given the exploratory nature of their analysis, and the findings as discussed are simplified for the same reason. “Increasing math achievement by 0.5 standard deviations” is far more easily done on a computer than accomplished in practice, but real-world research has shown that there are many ways both inside and outside the classroom to help students improve their math performance. Thus two important points emerge from this exercise. First is that policymakers can and should direct resources toward interventions and supports that are proven to provide the largest boost for the families they serve. This analysis suggests that math success in childhood is critical to adult—and lifetime—success. Second, we have multiple ways to accomplish in the real world what computer scientists can do with the click of a mouse. Urgent dedication from all stakeholders to the goal of improving math scores for students is required, with the broadest support and resources possible, as an investment in children’s (and families’ and society’s) futures.

SOURCE: Kevin Werner, Gregory Acs, and Kristin Blagg, “Comparing the Long-Term Impacts of Different Child Well-Being Improvements,” Urban Institute (March 2024).

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- Lots of voucher grouching over the weekend, including multiple different takes on the ridiculous notion that it’s a bad thing that there wasn’t a mass exodus of students out of school districts in the first year of near-universal voucher availability in Ohio. Our Aaron Churchill is the sole pro-voucher interviewee included in this Statehouse News piece, but his calm voice of reason is nearly drowned out by the sheer volume of nonsensical bellyaching that otherwise comprises the story. (Statehouse News Bureau, 6/17/24) The Spectrum, a local TV news show, includes School Choice Ohio boss Yitz Frank as its main voice of voucher support. But his calm analysis and serious answers are no match for “random outraged taxpayer” (who probably only fits two of those descriptors BTW), whose unanchored comments start at 11 and only go up from there. Too bad, Rabbi. (NBC4 News, Columbus, 6/16/24) Finally, the Dayton Daily News included the comments of exactly three legislators in today’s “leaders respond” article regarding EdChoice expansion data published last week—two haters and one supporter. (Dayton Daily News, 6/17/24)

- To all of those voucher grouchers complaining that EdChoice expansion did not result in a mass exodus of district school students to private schools, I have just two things to say. First is “Please read this Dispatch piece discussing how bad math and reading proficiency in Ohio’s public schools were in 2022, per the latest Kids Count Data Book.” (Columbus Dispatch, 6/17/24) Second is “Just wait.”

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Stories featured in Ohio Charter News Weekly may require a paid subscription to read in full.

New Ohio charter research

Ohio State University professor and Fordham Ohio’s Senior Research Fellow, Dr. Stéphane Lavertu, published new research this week looking at the academic performance of brick-and-mortar charter school students in comparison to their traditional district peers. This is the follow up to a previous pre-pandemic study which found a significant academic boost for charter students. The new analysis examines student-growth data from 2021–22 and 2022–23 and concludes that brick-and-mortar charters continue to outperform nearby districts. While the charter advantage is slightly smaller than pre-pandemic, Lavertu estimates that charter students gained the equivalent of roughly 13 and 9 additional days of learning in English language arts and math, respectively, when compared to their district peers.

Charters on the grow around the state

Heir Force Community School in Lima is expanding, planning to add room for more than 100 additional students in its new facility by fall 2025. Their efforts include a new classroom building and more greenspace to provide greater recreational opportunities for students. In Canton, both Summit Academy charter schools and Wright Preparatory Academy have recently purchased decommissioned Catholic school buildings in different parts of town. Wright Prep is already operating in the former St. Paul School, while Summit has no immediate expansion plans for St. Mary’s of the Immaculate Conception but expects to need more space in the near future.

Cautionary tale

Any charter operators looking to buy decades-old school buildings would do well to pay attention to this cautionary tale: ACCEL Schools Ohio LLC was issued a notice by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency this week for asbestos and lead paint concerns at three of its schools in northeast Ohio. There is a list of necessary remediation efforts that must be completed before students and staff can again access the buildings and EPA oversight will likely continue until all requirements are met. Additional note: Schools are required by EPA to have up-to-date asbestos management plans.

Research on virtual tutoring

A recent study out of Texas analyzes the benefits of virtual tutoring specifically for early elementary students. Data come from twelve Texas charter schools who were utilizing the OnYourMark Education remote tutoring platform to help boost achievement for their youngest readers. While the intervention didn’t help boost all students, the benefits were widespread and efficient given the lower cost and simple logistics of the online effort.

Making a national splash

Fordham Foundation-sponsored charter school Columbus Collegiate Academy – Main featured heavily in a RealClearInvestigations piece looking at the origins of, concerns about, and evolution of the No Excuses model of school operation. The big question here is whether the model is ripe for a comeback, but the in-depth look at CCA indicates that never really went away in schools with a dedicated and compassionate group of teachers and staff members who want to do what’s right for their students. This includes loosening the rigid rules a little when that promises to help move kids forward more than strict adherence will. A detailed discussion well worth your time.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- The elected school board in the bougiest school district in central Ohio (that’s Upper Arlington City Schools, if I do say so myself), whose resident families stand to gain the least should they decide to pursue an EdChoice Scholarship, voted this week to spend a portion of their state per-pupil funding to battle the state in court via the voucher groucher lawsuit. Charming. (Columbus Dispatch, 6/12/24) Meanwhile, the elected school board in Groveport-Madison Local Schools voted this week to table a resolution authorizing joining the lawsuit. This despite the fact that hundreds of district-resident students opt for vouchers instead of the district schools (as we are told in the piece) and despite the fact that G-M is still embroiled in whatever remains of the state’s effort to enforce transportation compliance for charter, STEM, and, yes, private school students (which is not included in the piece, but your humble clips compiler has a long memory for these things). Guess the elected school board members figured they had more important things to contend with than paying somebody else’s lawyers…at least for now. (Columbus Dispatch, 6/13/24)

- Speaking of school districts with money to burn (were we?): Here’s a look at the portfolio of closed buildings and other vacant properties currently owned by Columbus City Schools. Taking away the rhetoric (and there’s lots of it here, don’t you worry), the math goes like this: $400K in annual maintenance expenses. $134K in annual rental income. And $0 in sales on these multi-million-dollar properties. (Columbus Dispatch, 6/12/24)

- Meanwhile, oops! The Department of Education and Workforce reported this week that schools of all types across the state—along with other student-focused entities like career centers and county boards of developmental disabilities—were overpaid to the tune of around $30 million this fiscal year. It all stems, we are told, from incomplete information provided by an unknown number of districts at the start of the funding cycle, which led to erroneous calculations of per-student funding requirements for the schools themselves, voucher program participants, and more. Examples given: Columbus City Schools was overpaid by $883,000; Cleveland Metropolitan School District by $696,000. (Cleveland.com, 6/13/24) The good news is that the legislature plans to pass a fix in the next couple of weeks so that the same problem doesn’t recur in the new fiscal year. The even better news is that the legislature does not plan to try and recoup any of the additional funding schools and other entities received in error, with the Senate President declaring it “messy” to try and do so now. (Gongwer Ohio, 6/13/24)

- In other news, ACLD School & Learning Center—a private school in the Youngstown area that serves student on the autism spectrum and those living and growing with other learning challenges—is celebrating receipt of a very generous private donation toward the expansion of their campus, which is currently underway. More programming, more space for students, more awesomeness, all coming soon. Amazing! (Yes, they do accept Jon Peterson Special Needs and Ohio Autism Scholarship students. I checked ahead of time because I knew you would ask.) (Vindy.com, 6/13/24) A two-for-one report of good news to end the week. Heir Force Community School in Lima is on the grow, planning to add room for more than 100 additional students in its new facility by fall 2025. Toward the end of the piece, we also learn that Temple Christian School is expanding to house more students after its enrollment grew by 15 percent last school year. (Probably due to those EdChoice voucher students that they accept. Yep. I checked them too.) Woohoo! (Lima News, 6/13/24)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

It’s no secret that the public-school establishment pulls out all the stops to prevent families from exercising educational choice, including private school options. More than one hundred school districts, for instance, have lined up in support of a lawsuit that aims to kill in one fell swoop EdChoice, a program that provides state-funded scholarships for about 125,000 Ohio students to attend private schools.

Their latest strategy: tying up private schools in red tape in an effort to weaken them via a thousand regulatory cuts. Introduced earlier this spring, the vehicle for this broadside is House Bill 407. The legislation would heap a number of new and intrusive reporting requirements on private schools regarding their building capacities, admissions standards, expenditures, the income brackets that students’ parents are in, and the schools that students attended in the prior year. It would also reinstate a former requirement that private schools administer state assessments to scholarship students instead of permitting the use of alternative exams, and calls for some type of private school report card. While there is more merit to those outcome-driven proposals, they would discourage school participation in EdChoice and are being pushed, ironically, by education groups that have long resisted these types of accountability measures for their own schools.

Who exactly is advocating hardest for the bill? In committee testimony, the district school boards, superintendents, treasurers associations, and both teachers unions—the entire public-school establishment—voiced full support for the legislation. These longstanding opponents of private-school choice all plugged some variation of the argument that more regulation is needed to “level the playing field” and to help parents access more information about private schools.

Let’s be clear from the start: This effort isn’t about fair competition or parental empowerment. Rather, it’s blatant, anti-competitive behavior cloaked in “accountability.” What the public-school groups are doing is no different than corporations lobbying for policies and regulations that prevent the competition from gaining a foothold. None of these groups have ever argued to increase private school funding to bring their amounts in line with public schools (that would bring some “fairness” to the table). It’s also hard to say that parental rights is their focus when they file lawsuits aimed at robbing families of school choice and constantly ridicule programs that provide more options. It’s also tough to take the testing requirement seriously when pushed by groups that regularly attack state tests. And report cards? Just a few years ago, these very groups (unsuccessfully) lobbied the legislature for an opaque public school report card that would have been useless to parents.

But since private school accountability is at issue—and because they are often criticized by their opponents as being “unaccountable”—it’s worth reviewing yet again the ways in which private schools are accountable.

First and foremost, private schools are directly accountable to the families they serve. When parents are dissatisfied, they can head for the exits. One might say the same is true for public schools. The difference is that private schools no longer receive funding when a student leaves—they lose the state scholarship amount, if applicable, plus any tuition along with the student. If they suffer significant enrollment and financial losses, they have no choice but to close their doors. This form of accountability—financial consequences directly tied to enrollment losses—is a key incentive for private schools to provide a quality education.

Traditional districts, on the other hand, are shielded from the financial pain of enrollment declines through the state’s longstanding use of funding guarantees and local property tax revenues that are not tied to enrollment. Moreover, because a school district must cover every corner of the state, districts have built-in protections from permanent closure. The weaker “market discipline” in the district sector is one reason why school reformers have typically pursued results-driven accountability measures that incentivize districts to pay attention to the needs of students.

Remember also that Ohio’s private schools are already held to many of the same standards as traditional public schools. They must be formally “chartered”—a form of accreditation—by the state,[1] and through that process, they must adhere to the state operating standards that apply to public schools, as well. Moreover, a school’s charter can be revoked for noncompliance with state laws and regulations, and they must follow racial nondiscrimination policies. This regulatory structure makes sense, balancing school autonomy with necessary guardrails, and has served Ohio well for decades.

As for academic outcomes, Ohio has long required scholarship students in particular grades to take a standardized exam. As noted earlier, students were formerly required to take the state test, and their proficiency rates were reported in the aggregate for each school. In 2019, the General Assembly changed the law to allow private schools to administer a state-approved alternative exam that might align more closely with a school’s curriculum. Proficiency rates on these tests are still reported and, last year, state lawmakers added an important new requirement: Scholarship students’ growth results will now be calculated and reported, as well. This additional data point (which entails no new testing burdens) will soon provide a clearer picture of the yearly academic progress of students attending private schools. Lawmakers would be smart to see how the state’s new growth measure helps inform the public before turning back the clock on assessment or instituting a report card system.

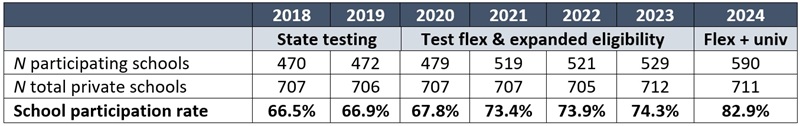

It’s important to recognize that adding further regulations on top of the existing framework would only discourage private schools from participating in EdChoice—indeed, very conceivably what the public-school groups hope will happen. In Louisiana—a state with onerous regulations—only one-third of private schools decided to participate in its scholarship program, thus limiting the choices of families and likely to schools of lessor quality. Fortunately, as the table below indicates, Ohio has done better, as two in three private schools participated in EdChoice as of 2018–19. With expanded eligibility and testing flexibility, four in five accepted EdChoice scholarships this past year. Increasing state regulations, as HB 407 proposes, could wipe out this progress in private-school participation.

Table 1: Private school participation rates in EdChoice (income-based or low-performing schools)

Back in 2016, along with my colleague Chad Aldis, I wrote: “Policymakers should tread lightly when adding to schools’ regulatory burdens. After all, freedom from regulation is precisely what makes private schools different and—for many—worth attending in the first place.” I stand by that statement. Rather than pursuing ill-advised attempts to conform private schools into the image of public schools, the state should allow for distinctive schools that meet the varying needs of Ohio families.

[1] Private schools eligible to participate in EdChoice are technically known as “chartered, nonpublic schools.” These schools are not the same as public charter schools.

A good case can be made that, to the degree K–12 education in the U.S. has embraced high-quality instructional materials (HQIM), the movement began just over a decade ago with EngageNY.

Launched in 2011 with $700 million in federal “Race to the Top” funding to support the implementation of the Common Core State Standards, EngageNY provided a comprehensive suite of free, downloadable instructional materials in English language arts and math. It also demonstrated convincingly that districts, schools, and teachers across the country were starved for quality curriculum: Its resources became even more widely used outside the Empire State than by the teachers for whom it was built. A 2015 RAND survey found that one in four English teachers nationwide were using EngageNY. Uptake for math teachers was even higher. The vast majority of teachers surveyed reported their districts either required or recommended that they use it.

New York State stopped supporting EngageNY two years ago. But a new open educational resource has just debuted that has the potential to pick up where it left off. The Texas Education Agency has spent three years piloting a promising set of ELA materials, which became freely available late last month: a structured and sequenced, knowledge- and vocabulary-rich curriculum for kindergarten through fifth grade, including reading materials, teacher’s guides, activity books, and supporting resources—all online, all downloadable, all free to anybody who wants to use it.

That said, if you’ve heard anything at all about this initiative, it’s probably that Texas is trying to “inject Bible stories” into its elementary school classrooms. When The 74 broke news of the project, its headline said the Texas initiative “raises questions about ‘religious and ideological agendas.’” A report in the Washington Post this week said “it is clear the materials include many religious references that center Christianity.” This framing is unfortunate and frustrating. Unfortunate because it’s distracted attention from the fact that Texas seems to well and truly understand the ingredients of language proficiency. And frustrating because, if your takeaway is that the curriculum doesn’t grant “equal time” to other religions (as one Texas state lawmaker put it), you’re not seeing language proficiency for what it is and how it works. And this understanding is particularly important for low-income students.

To state it bluntly, “equity” is not bean-counting, it’s literacy. Speakers and writers make assumptions about what listeners and readers know. Not just vocabulary, but a vast array of literary and historical allusions and idioms, including Biblical references—Pandora’s box, a pound of flesh, Prodigal Son, Good Samaritan, David and Goliath, forbidden fruit, white whale, to name but a few. These and countless other examples act as a kind of shorthand for complex ideas and concepts. They color our language and, most pertinently, they are broadly shared bits of common knowledge that literate people simply drop into their discourse without any explanation whatsoever. Those who get these references are language-haves; those who don’t are language have-nots and will always be at a verbal disadvantage. Not for nothing did E.D. Hirsch, Jr. title his first and most famous book Cultural Literacy. It refers to the ability to understand and use the information and references that are common in a culture. For decades, Hirsch has passionately and unimpeachably argued that possession of this shared body of knowledge is crucial to reading comprehension, effective communication, social inclusion, and citizenship.

Seen through this lens, designing an effective curriculum isn’t an exercise in canon-making (“learn this because I said so!”). It’s a curatorial effort: Learn this because literate speakers and writers assume you know it and you’ll be at an enormous disadvantage if you don’t. Every effort must be made to ensure that students, particularly disadvantaged students and English learners are conversant in literature, history, science, the arts, and yes, the Bible—the robust array of mental furniture that their well-off peers take for granted, and upon which mature language proficiency depends. Equity, properly understood, demands nothing less. Hirsch himself said it best: “Public education has no more right to continue to foster segregated knowledge than it has to foster segregated schools.”

This was clearly on the mind of Texas leaders, including Commissioner of Education Mike Morath, who previewed the state’s new OER curriculum for me last month. “Clearly, you have to have a very skilled principal and skilled teachers. But there’s an aspect of curriculum design that’s critical in order for reading comprehension to grow,” he explained. “You have to have explicit, systematic direct instruction in phonics. You have to have vocabulary complexity. You have to have knowledge coherence as opposed to skill coherence in the design of your units and lessons. And you have to write a lot in response to reading.” Hear, hear.

Echoing previous studies that have shown that disadvantaged students tend to get low-rigor, unchallenging schoolwork, Morath said the Texas Education Agency replicated TNTP’s well-known “Opportunity Myth” study in twenty-seven Texas school districts and found that, “in elementary school reading, only 19 percent of the assignments we sampled were on grade level.” This sets in motion a cycle of underperformance, he noted, “because teachers aren’t deliberately doing this.” Kids, too, might not realize they’re working diligently but on material that’s below grade level. “Then the state assessment comes around and says you’re not performing at grade level. And everybody’s like, ‘What gives?’”

Close observers of curriculum will recognize that the Texas “OER” (open educational resource) is an adaptation of the well-regarded Core Knowledge Language Arts curriculum, which a Texas Education Agency spokesperson confirmed was “purchased as a foundational product and then overhauled based on feedback to align to Texas state standards, research-based instructional practices, and recommendations from the field.” With 9,000 campuses, 4,500 elementary schools, and 400,000 teachers, “no one should expect a miracle overnight,” Morath said. “But we’re moving in a very evidence-based direction in Texas.” Initial results from districts that have piloted the curriculum, he added, are “not universal, but promising.” The majority Hispanic and low-income Temple Independent School District in Central Texas, for example, has seen a 13 percent jump in third graders meeting standards compared to pre-Covid levels. Results were even stronger in Lubbock, which has similar demographics and saw a 21 percent rise in African American third graders meeting standards, and 19 percent of Hispanics in its first year of implementation. “It’s not just the rising tide is lifting all ships. We have some evidence base that this disproportionately lifts the ships of kids who have been the most academically at risk,” Morath observed.

As for the Bible stories controversy, Morath said via email this week, “We are actively taking feedback on the product and will make updates to address any errors that are surfaced to ensure that references to any religious tradition(s) are done accurately and reinforce the intended purposes of bolstering understanding of literature, history, and culture.” It would be lamentable, however, if that controversy derailed or neutered a project that has the potential to benefit students nationwide, further the HQIM movement, and advance the field’s sophistication on what language proficiency requires.

It’s commonly observed that a dictionary isn’t a rule book, it’s a history book. It doesn’t tell you how words must be used, only how they have been used. The same basic idea runs throughout language at large: You can’t control or impose your will on it. But you can teach it. This is the Achilles’ heel (see what I did there?) of those who think they’re striking a blow for social justice by “decolonizing” curriculum or whose view of equity is limited to mere “inclusion.” They are at grave risk of imposing a kind of illiteracy on disadvantaged children by denying them access to knowledge and vocabulary that is essential for mature language proficiency.

The bottom line: If you think Bible stories are inappropriate in a public school ELA curriculum, let Texas’s important new OER curriculum be your come-to-Jesus moment.