In recent years, discussions about advanced and gifted education have revolved around expanding access, and last year’s final report from the National Working Group on Advanced Education offered numerous recommendations for how schools and districts can make these programs work better, and for more students. But what policies and practices do districts actually have in place for their advanced learners?

To find out, the Fordham Institute’s Adam Tyner surveyed school districts and charter networks about their approach to advanced education, including types of identification policies, comprehensiveness of advanced services, and the kinds of supports offered to teachers.

Overall, the state of advanced education in America’s school districts is mediocre. Although a few best practices have been widely adopted, most districts neglect valuable policies that could expand access and improve student outcomes, resulting in a broken pipeline in advanced education.

Download the full report or read it below.

Foreword

by Amber M. Northern and Michael J. Petrilli

1998 was a rambunctious year, as both Google and iMac arrived, Bill and Monica made headlines, and Seinfeld ended with a widely-panned finale. It was also the year that we at Fordham published our very first report on advanced education. It dealt with tracking and ability grouping and was authored by Tom Loveless.

Since then, we’ve published fourteen other reports or books on how to improve education for America’s high achievers. Suffice to say we’ve been among a wee group of reformers interested in that topic over the last twenty-five years. Wee because too many assume that advanced education is about increasing privileges for the already advantaged, rather than identifying and maximizing the strengths and potential of every student—including poor kids and kids of color with potential for high academic achievement.

This disregard has resulted in serious neglect of a vital student subgroup, with future national repercussions for weakened, less diverse leadership and less innovation, progress, and economic growth. More pragmatically, it has also resulted in a lack of informative research for the field of advanced education.

This latest report on the plight of advanced learners—our sweet sixteenth, if you will—aims to address just one of many unknowns: whether districts nationwide have adopted policies and programs to identify, support, and cultivate the talents of all students capable of tackling advanced-level work.

The Fordham Institute’s National Research Director, Adam Tyner, was keen to conduct the investigation, having previously completed research on gifted education in high-poverty schools. Adam also participated in The National Working Group on Advanced Education, convened by Fordham in spring 2022 to promote research, policies, and practices that will build a wider, more diverse pipeline of advanced learners. The culmination of that group’s yeoman work was the 2023 release of dozens of recommendations to aid state and local officials in developing a continuum of advanced learning opportunities across K–12.

The key aim of the current project was to determine whether districts had in place policies that aligned to any of the National Working Group’s recommendations. Thus, from May through October 2023, we surveyed a randomly selected sample of district and charter school administrators in charge of advanced education. Nearly 600 responded, and using stratified weighting, we adjusted the results to be representative of large and medium districts and charter school organizations, which together educate 90 percent of public-school students. So, to what extent have districts adopted smart approaches to advanced education? To some extent, but not nearly enough.

Adam aggregated the various district policies recommended by the Working Group such that a district (or charter network) could earn a total of 1,000 points. The results showed that the typical (median) district earned less than half of the possible points (485 out of 1,000), a majority earned 350 to 600 points, and only one-fourth of districts earned more than 600 points. Were the rubric translated into a traditional A–F scale, three-fourths of the districts and charter networks would flunk. That leaves a lot of room for improvement.

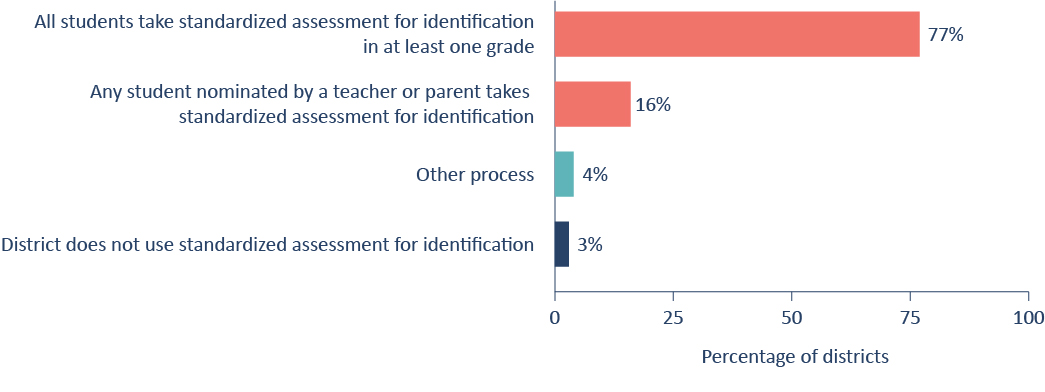

Still, we were pleasantly surprised to discover that it’s quite common for districts to universally screen students for advanced education services based on their performance on standardized assessments. Specifically, more than three-fourths of districts with advanced programs in K–8 reported screening all students using a standardized assessment, at least in one grade. Given the strong research backing for “universal screening,” that’s an encouraging finding.

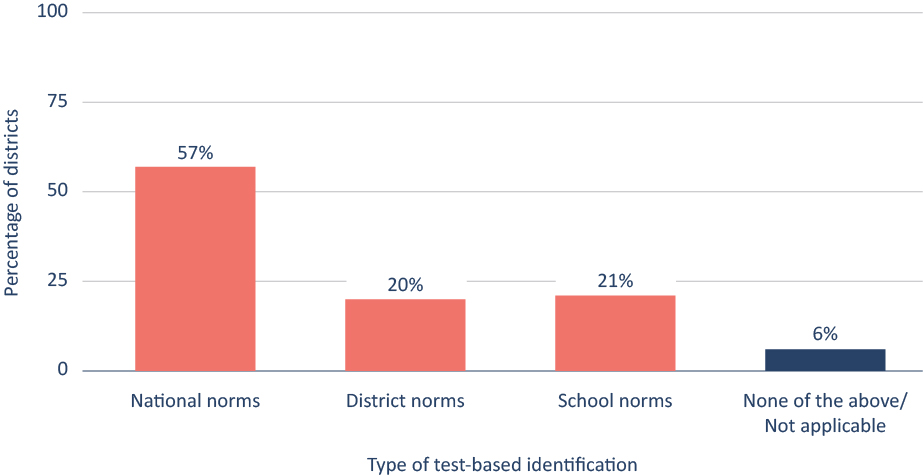

Yet other worthy identification policies are scarce—in particular, screening students for advanced programming based on their “local” peers’ academic performance. In fact, only one-fifth of respondents say that their districts compare students’ performance to peers within the same district or school for identification purposes (a.k.a. “local norms”)—rather than a state or national benchmark. Applying local norms—such as identifying students performing in the top 10 percent of their school—helps to detect a wider swath of advanced and potentially advanced children, especially those in high-poverty schools, and deserves more consideration.

We also found some encouraging evidence in elementary schools of the popularity of part-time pull-out classes for high achievers, giving those students an opportunity to engage with peers of similar abilities on advanced curriculum (45 percent of districts offer this). On the other hand, districts rarely ever accelerate young students by grade level or content area (no more than 4 percent of them), which enables children to “skip a grade”—either in all subject areas or one, say, math.

As for actual entry into advanced services, over half of districts do not allow early entry into kindergarten based on children’s readiness. But nearly the same percentage allows those who participate in advanced education in elementary school to be automatically enrolled in advanced courses in middle school and beyond.

So, it’s quite a mixed bag, containing ample room for improvement. We see two overarching takeaways.

First, the identification side of advanced education is in better shape than the programmatic side. As indicated, a majority of districts use various assessments to screen elementary and middle school students for advanced programming, including performance on cognitive tests, diagnostic assessments, and state-mandated or other end-of-grade tests. Over three-quarters of districts (77 percent) use a standardized test to screen all students in one or more grades.

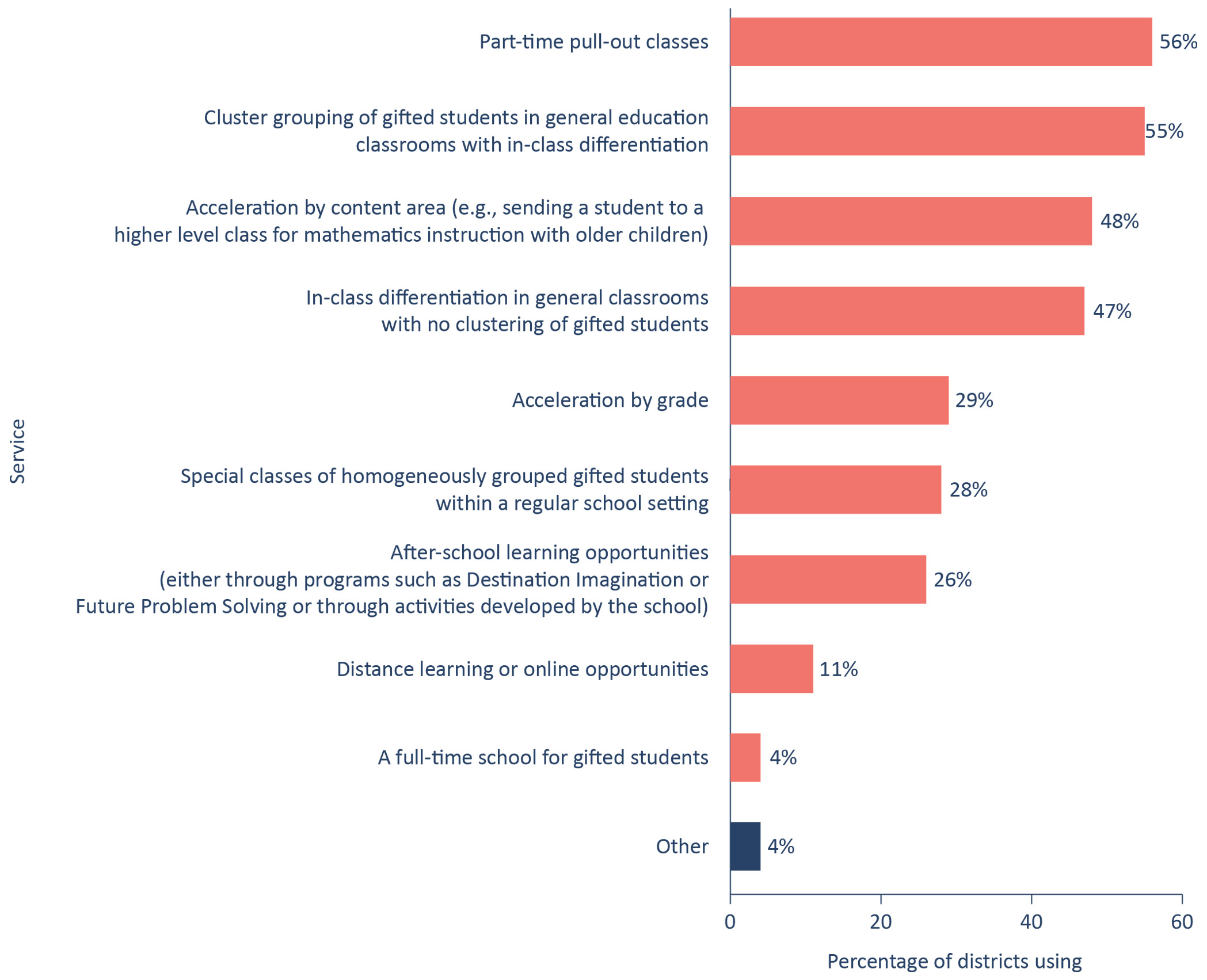

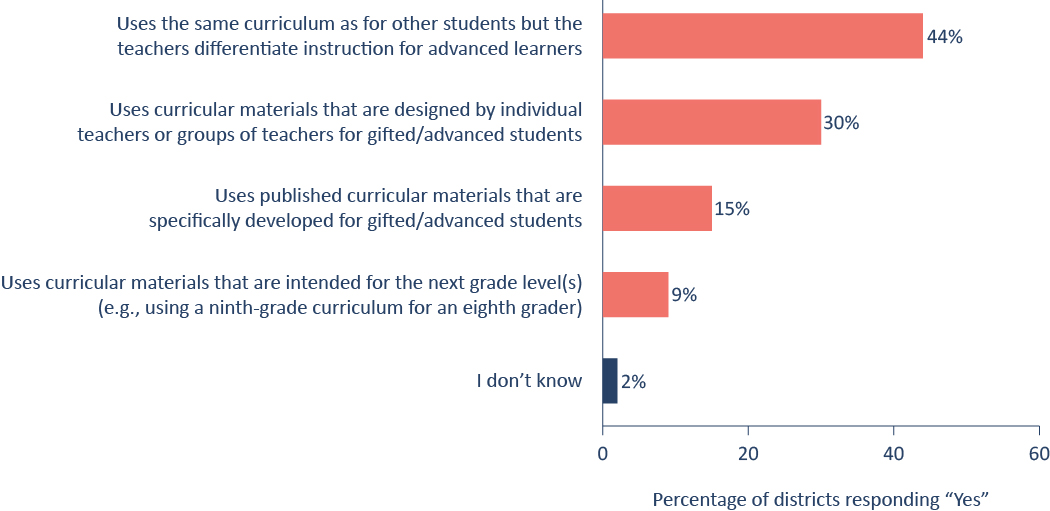

But there is so much more that districts should and could be doing for advanced learners once they are identified, especially in the early grades. Nearly half report that one of the most common types of advanced programming in elementary and middle schools is “in-class differentiation in general classrooms with no clustering of gifted students.” It’s not hard to see the drawbacks to that approach—as Tom Loveless pointed out so many years ago. Likewise, 44 percent report using the same curriculum for advanced students as for other students, albeit with some modification. Barely 11 percent of districts report offering distance or online learning opportunities for advanced learners in the elementary and middle grades. Come on—clearly, we can do better!

Second, the difficulties associated with providing advanced education are most keenly felt in the latter elementary grades (after students are identified) and in the middle grades, when advanced courses are often limited to math. Once students get to high school, they typically have more opportunities to be challenged. In fact, 58 to 80 percent of districts offer high school honors classes in one or more core subjects, and two-thirds of districts—according to federal data—offer AP Math or AP Science classes (though with clear variation among schools within districts). About half of districts also expand access to advanced courses by allowing high school students to take AP or IB courses online.

To our eyes, then, there’s a sizeable leak in the pipeline after early elementary school, when students are identified for advanced services, and the high school grades, when they gain more exposure to advanced courses, both in person and online. But not nearly enough is happening in between. Hence the title of this report, The Broken Pipeline.

Still, leaks or not, we aren’t glass-half-empty types. Our glass-half-full view is that broken pipes can be fixed. So let’s get out those wrenches!

Introduction and background

In the shadow of a national reckoning on racial equity and in the wake of high-profile debates on the future of advanced (or “gifted”) education, advanced education in the United States stands at a critical juncture.[1] In recent years, the spotlight has been on the pressing need to reassess and revitalize the policies that govern our nation’s approach to nurturing exceptional academic talent. This urgency is fueled not just by a desire to cultivate the potential of America’s most academically talented students, but also by a commitment to advancing equity and expanding opportunities for all students, regardless of their racial or socioeconomic background, and by the necessity that America remain economically competitive.

The controversies and challenges that have arisen in the world of advanced education—from debates over curriculum changes to lawsuits over admissions policies—signal a broader national conversation about how we value and nurture intellectual talent. They also reflect deep-seated concerns about fairness, opportunity, and the role of education in boosting upward mobility. At the same time, research points a way toward sets of school district policies that can unlock both academic excellence and greater educational equity. For example, a recent report from the Fordham Institute–sponsored National Working Group on Advanced Education recommends 27 policies for school districts to implement[2], which reflect research and practices in pursuit of a wider and more inclusive talent pipeline.

Those 27 policies include the Working Group’s best advice about identifying students for advanced learning, determining what services such students should be offered, and providing effective supports for teachers. Many of these recommendations are based on solid evidence, such as Working Group member Laura Giuliano’s research (with David Card) on the effect of universal screening for advanced programs. That pathbreaking work showed that universal screening using achievement tests is a more equitable method of identifying gifted students than traditional methods, which often lean heavily on recommendations by teachers and parents.[3] Universal screening allows all students to showcase both their current performance and their potential, ultimately leading to more inclusive representation of low-income and minority students in advanced education.

Substantial recent research has also shown the power of offering students the opportunity to accelerate—that is, to work on content they would normally encounter in later grades[4]—and of using “local norms” to identify students in individual buildings or schools rather than using national or state cutoffs.[5] Evidence in support of other policies is sparse, but there remain solid reasons to believe that the best programs will have particular features, such as providing professional development for teachers to understand the needs of advanced learners and evaluating student needs often so that a classification of “advanced” or “not advanced” does not follow students after their needs change.

Background research

Previous descriptions and analyses of district and school policies and practices for advanced education are dated and thus do not capture recent research, policy trends, or shifts induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, and none of them evaluate the extent to which policies are well aligned to best practices for promoting excellence and equity, such as those recommended by the National Working Group on Advanced Education. The most similar effort in recent years was undertaken by researchers at the University of Virginia.[6] The results of their survey of districts were released in 2013, and in the present study we included two questions that closely mirror that survey to gauge the extent to which those policy patterns have persisted (see Appendix D). A 2019 survey of teachers and school, district, and state administrators by the magazine EdWeek provided additional information about local and state policies, although the predominance of teachers in the respondent pool made the results somewhat difficult to interpret.[7]

Other research has examined participation in advanced programming across schools, with special attention paid to differences based on student demographics. For example, a 2022 study demonstrated the importance of state-level variation, finding that advanced education rates varied significantly depending on the state.[8] A 2018 study by the Fordham Institute also showed that the prevalence of schools reporting advanced programming did not vary by school poverty rates,[9] and a follow-up 2021 study by the same authors showed that the pattern persisted in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic.[10]

The limited availability of information on present-day advanced education policies and practices at the district level underscores the necessity for the present survey. We seek a better understanding of district policies to identify, support, and cultivate the talents of students from all backgrounds who are capable of pursuing advanced coursework.

This report addresses three main questions:

- How comprehensive are the advanced education policies in America’s school districts?

- How common are specific evidence-based policies in advanced education, such as universal screening of students?

- Do district demographics predict the comprehensiveness of district policies?

Data and methodology

This report provides a national picture of advanced and gifted education policies across school districts. The data were gathered via Survey Monkey, with surveys completed by 581 district and charter administrators. Using post-stratification weighting, survey results were adjusted to be representative of large and medium districts and charter school organizations, which together educate 90 percent of public school students.[11]

The survey was designed by Fordham Institute staff to capture key dimensions of advanced education policies as reported by the National Working Group on Advanced Education. Members of the group also reviewed drafts of the survey and provided feedback. To help ensure that the questions would be well understood by district staff, the survey was piloted with gifted-education coordinators from diverse districts. The final survey also incorporated two questions that closely resembled those from scholars at the University of Virginia in 2013.[12]

From the sample frame of 5,610 large and medium districts, districts were selected randomly using statistical software to produce a contact pool of 3,659 districts. In each of these districts, Fordham Institute research staff identified one or two administrators whose position most closely aligned with advanced education, e.g., gifted coordinator or assistant superintendent for academics. District respondents were contacted through the survey platform, direct email solicitations, and phone calls and were encouraged to complete the brief questionnaire. They were assured that no individually identifiable data would be published and offered a $5.00 gift card for completing the survey.[13] In a few states, state coordinators for gifted policy agreed to assist our team’s efforts by encouraging the selected district administrators to complete the survey. The instrument was administered between May and October 2023.[14]

Alongside data from the survey, the analysis included publicly available data from the U.S. Department of Education. The Common Core of Data provided information on district size, poverty level, and student demographics that were used to implement the post-stratification weighting scheme and enable analysis of districts by their demographic profile. The analysis also included 2020–21 data from the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR), which collects data on the prevalence of Advanced Placement and participation in AP courses.

Findings

This section discusses the prevalence of advanced programming, the comprehensiveness of district policies, and five key findings of the report:

- America’s school district policies for advanced learners are mediocre at best.

- Good identification policies, such as universal screening, are common, but most districts do not adopt other best practices, including using local norms to identify advanced learners.

- Advanced programming in most elementary and middle schools is limited and of questionable value.

- Most high schools offer substantial advanced programming, although students may lack access if they do not meet the prerequisites.

- District demographics are not good predictors of district policies.

Prevalence of Advanced Programming

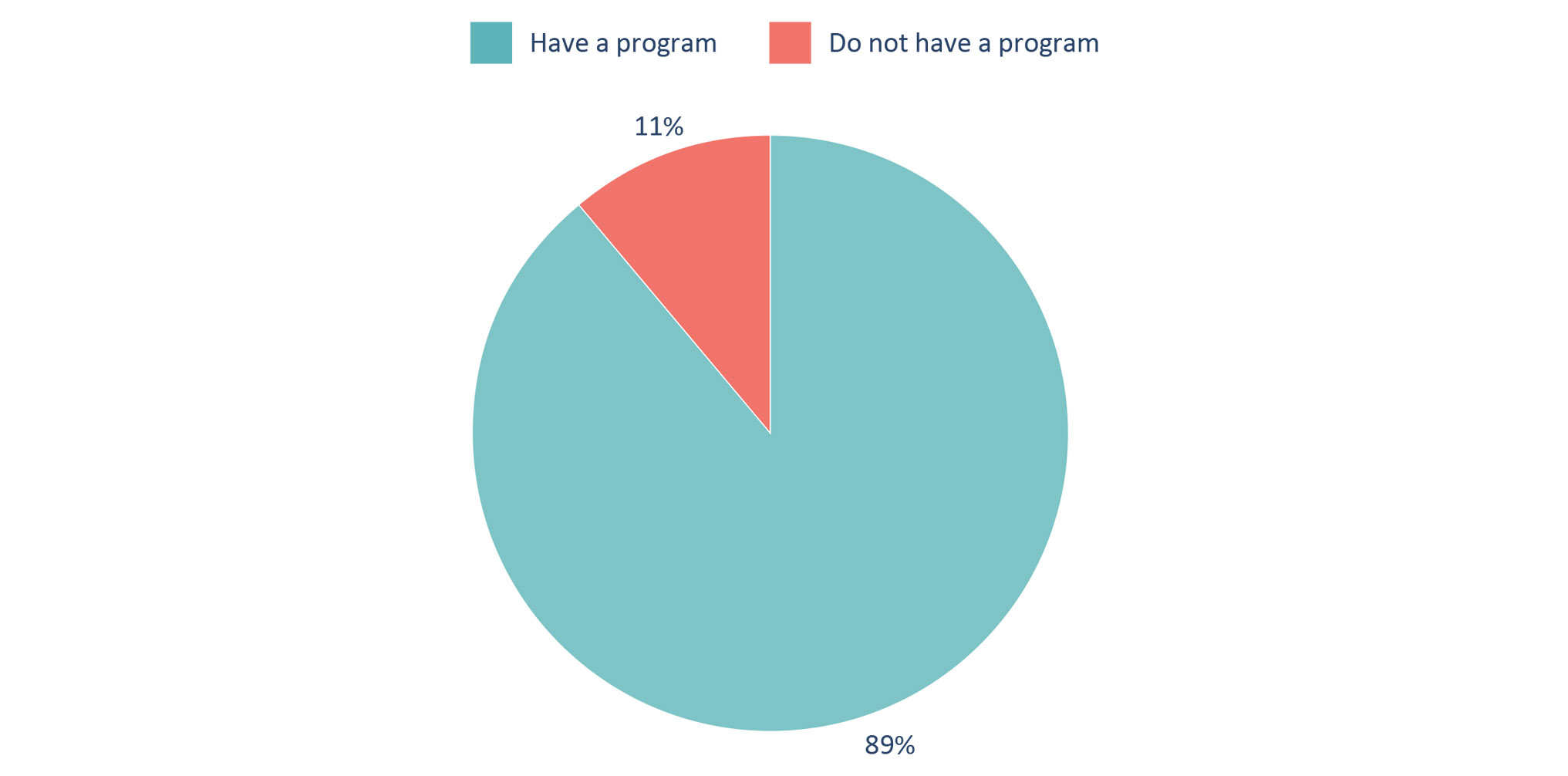

As shown in Figure 1, almost 90 percent of districts reported having some type of gifted or advanced programming for elementary and middle school students (kindergarten through eighth grade).

Figure 1. Eighty-nine percent of districts reported having some type of gifted or advanced programming for elementary or middle school students.

How comprehensive are district policies?

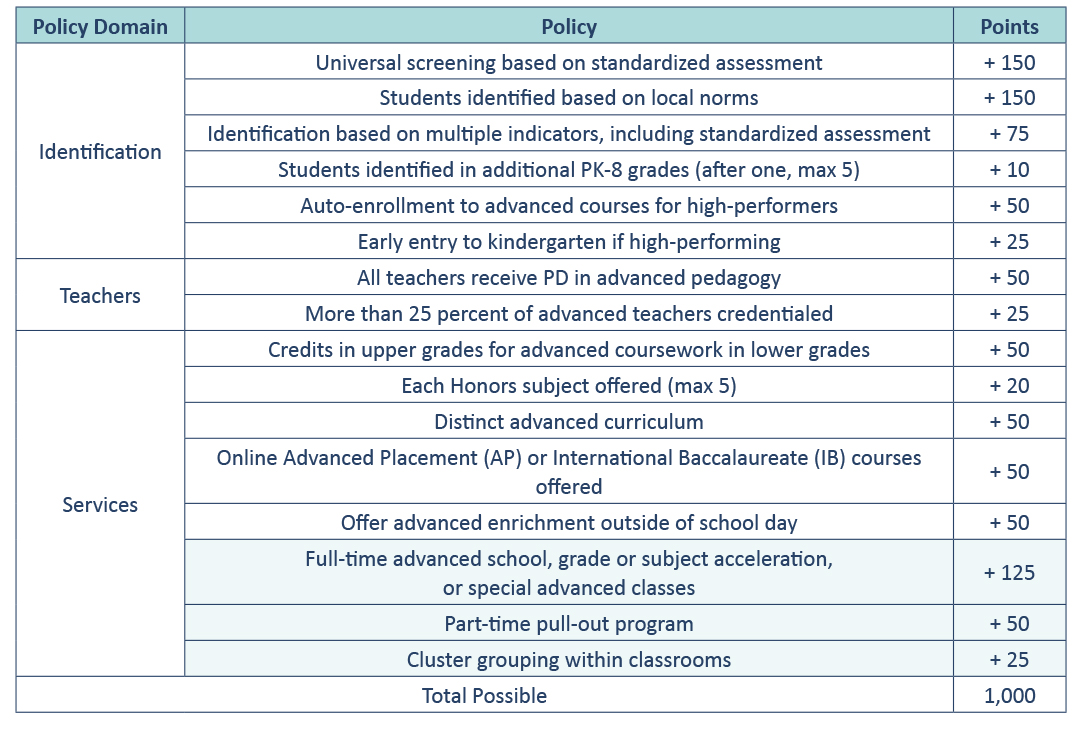

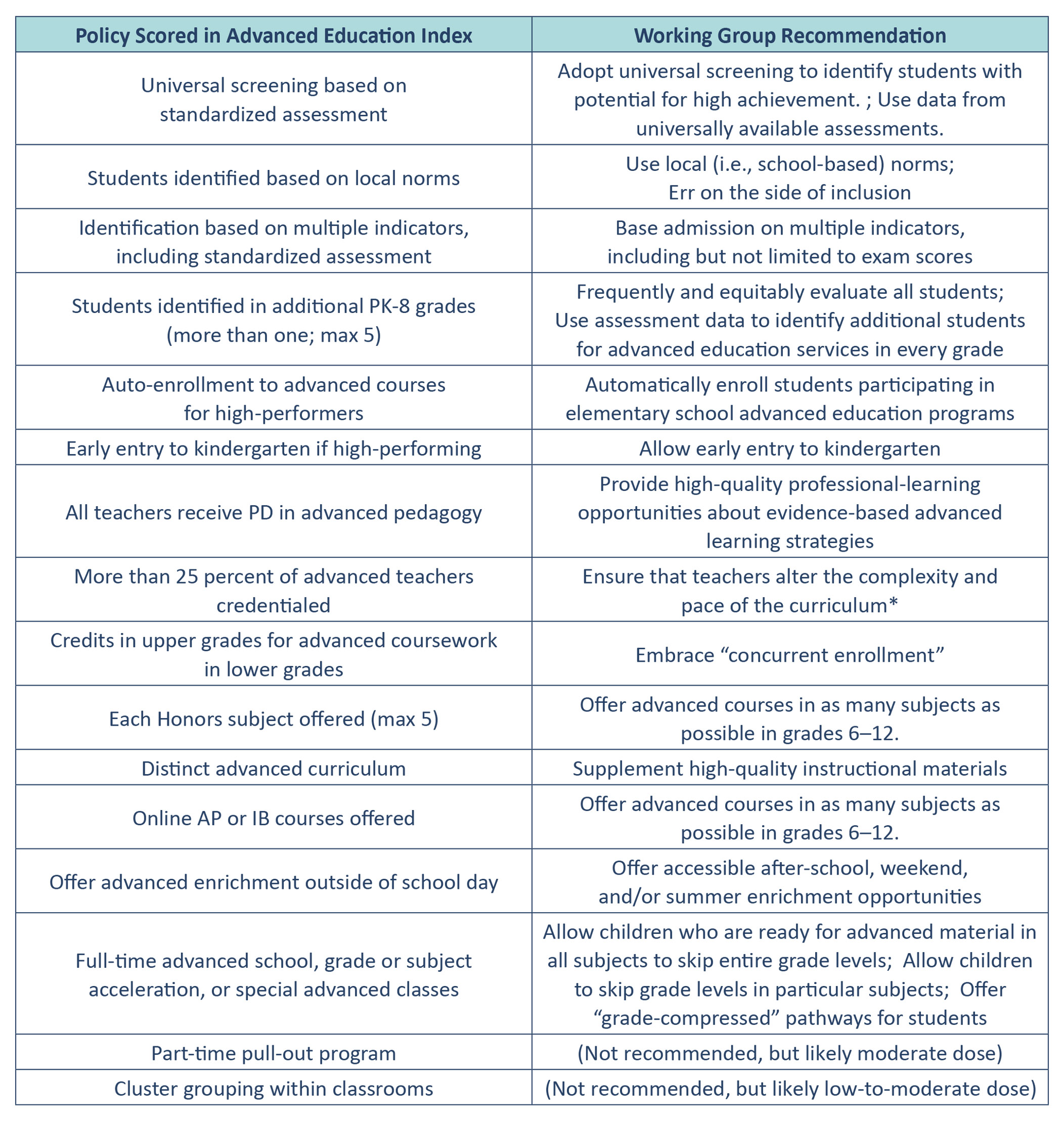

This section presents an overall picture of the comprehensiveness of the nation’s district policies, using an index score that is based on the recommendations of the National Working Group on Advanced Education.[15] (Specific policies are analyzed in later sections.) District policies are scored according to the schema in Table 1.

Table 1. The Advanced Education Index is based on recommended policies that make advanced education stronger and more equitable.

High-impact items such as universal screening and the availability of high-dosage learning opportunities (including full-time school, grade or subject acceleration, or special classes) are assigned relatively higher points (for definitions of key terms, see the Glossary). Good but generally lower-impact policies, such as allowing high-performing youngsters early entry into kindergarten, are assigned fewer points. Regarding the predominant way that districts provide services to advanced learners, districts receive the maximum number of points (+125) if they report the existence of a full-time school serving the needs of advanced learners, a grade or subject acceleration policy, or special advanced classes. They receive partial credit for having part-time pull-out programs (+50) or in-class cluster grouping (+25), which are not explicitly recommended but nonetheless superior to options like in-class differentiation with no grouping. To see how the Advanced Education Index aligns with the recommendations of the National Working Group report, see Table C1 in Appendix C.

Finding 1: America’s school district policies for advanced learners are mediocre at best.

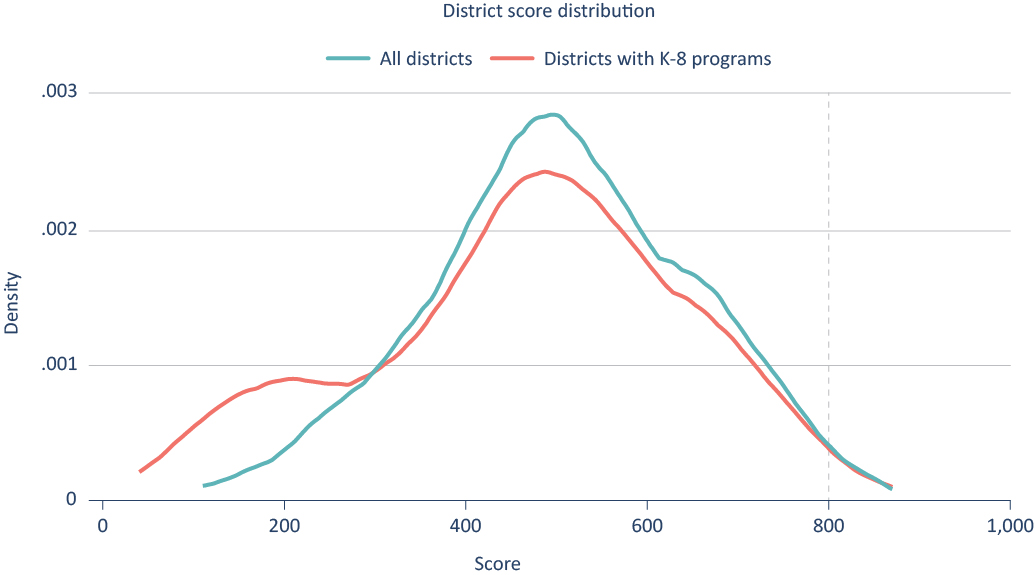

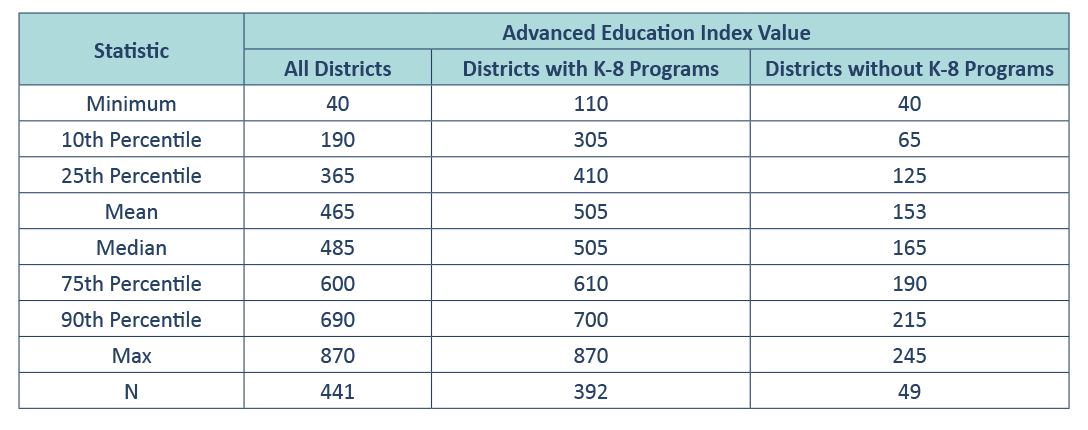

Aggregating the district policies shows that the typical (median) district earned less than half of the possible points, 485 out of 1,000, a majority of districts earned 350 to 600 points, and only one-fourth of districts earned more than 600 points (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The typical (median) district earns only around half of the possible points on the Advanced Education Index.

Still, as explained in the following sections, the vast majority of districts have at least a few policies that align with best practices for advanced learners: 90 percent of districts (10th percentile) earned 190 points or more (Table 2). For obvious reasons, districts that did not report any K–8 advanced education policies earned fewer points on the Advanced Education Index; their median score is just 165 out of 1,000 points. Among districts that did report some K–8 programs, the median score is 505, and 90 percent of these districts earned 305 or more points.

Table 2. Among all districts, 10 percent earned 40 points or less, while the best 10 percent of districts (at the 90th percentile) earned 690 points or more.

Identification

This section examines specific district policies for identifying students who would benefit from advanced education programs. Except where noted, the analysis in this section is limited to the 89 percent of districts that reported having some kind of gifted or advanced program in grades K through 8 (per Figure 1).

Finding 2: Good identification policies, such as universal screening, are common, but most districts do not adopt other best practices, including using local norms to identify advanced learners.

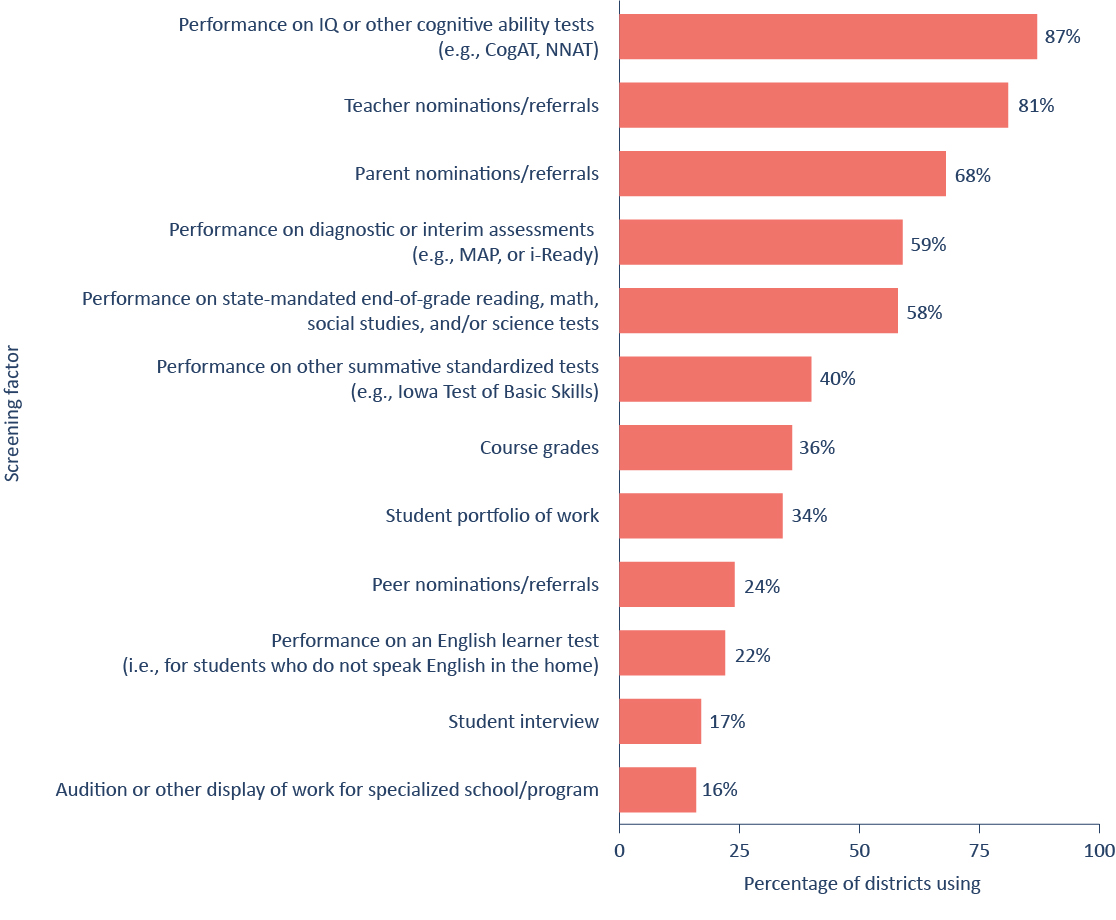

Districts reported using a wide array of factors to identify students who might benefit from advanced programs (Figure 3). Performance on a cognitive ability assessment is the most common factor (87 percent), but referrals from teachers and parents are also very common (81 percent and 68 percent, respectively). Most districts also use other tests, such as diagnostic assessments (59 percent) or state-mandated end-of-grade assessments (58 percent). Less than half of districts reported using course grades (36 percent), student portfolios (34 percent), or peer nominations (24 percent) for identification, and student interviews (17 percent) and auditions (16 percent) are rarely used.

Figure 3. The most common factors for screening elementary and middle school students for advanced programs are performance on cognitive ability tests, teacher recommendations, and parent recommendations.

While there are many ways to identify students for these programs and services, some methods cast a wider net than others. For example, even districts using some type of standardized assessment may not administer the assessment to all students. Figure 4 shows that universal screening based on a standardized assessment is quite common: more than three-fourths of districts with advanced programs in K–8 reported screening all students using a standardized assessment, at least in some grades. In 16 percent of districts, assessments are administered only to students nominated by a teacher or a parent.

Figure 4. A large majority of districts with advanced programs screen students universally using some type of standardized assessment.

Districts also vary in the achievement level required for identification (Figure 5). While using local norms for identification (such as the 10 percent highest scorers in a school) helps bring in a larger pool of advanced students, the majority of districts using test-based identification base their decisions on national norms (57 percent), not local (district or school) norms.

Figure 5. A minority of districts that screen students based on tests use local norms for identification.

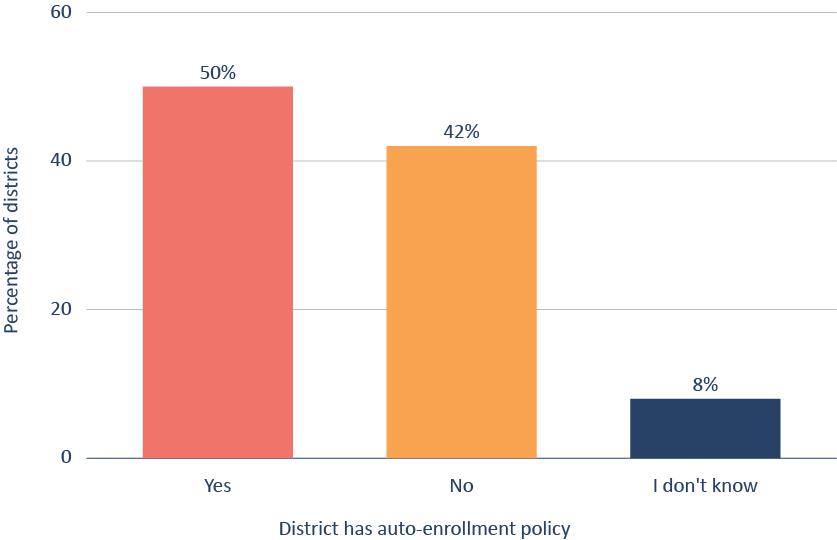

Another way districts identify advanced learners is by automatically enrolling students who participate in advanced education programs in later advanced courses. This can occur in elementary, middle, or high school grades. Half of districts reported having such a policy in place (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Half of districts have a policy of automatic enrollment that continues advanced education.

On-ramps

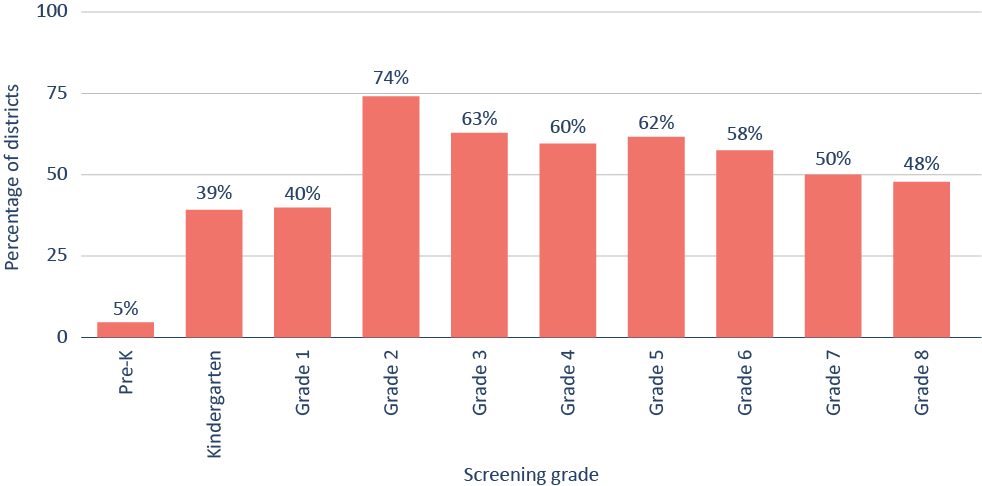

Identifying students for advanced programs can happen in any grade, but grade 2 is the most common identification point, and a majority of districts screen in grades 2 through 7 (Figure 7). It is rare for students to be screened before kindergarten, and relatively few districts screen during kindergarten (39 percent) or grade 1 (40 percent).

Figure 7. The most common grade for identification is grade 2, and few districts screen before kindergarten.

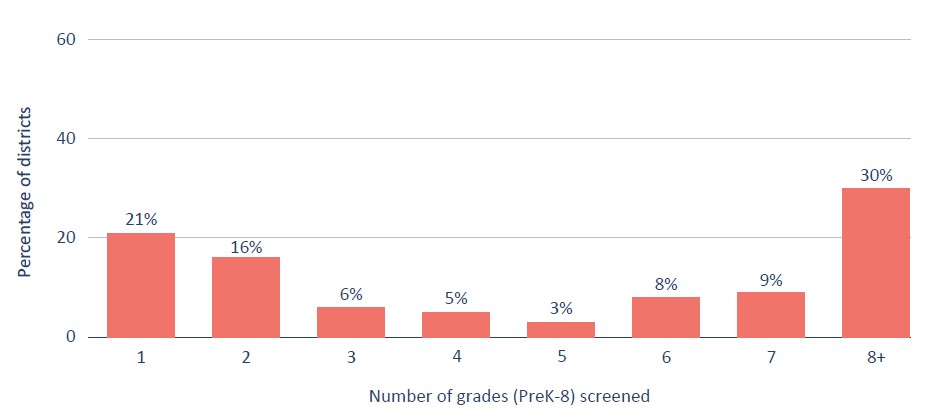

Most districts identify students at multiple points throughout elementary and middle school, but district policies vary widely in terms of how many “on-ramps” into advanced programs they provide (Figure 8). For example, does identification occur in only one grade for a given student, or can it happen at any point in an elementary or middle school student’s academic career? In fact, the identification process can be quite complicated in some districts, with different types of gateways at different grade levels. The vast majority of districts fall into one of two groups, offering either many on-ramps or very few. More than one-third of districts reported identifying students in only one or two grades, but at the other end of the spectrum, almost half of districts reported that they screen students in six or more grades. Still, comments from district administrators indicate that many conduct screening in only specific grades, and although students can be screened in other grades, those screenings occur only after the referral of a teacher or parent.

Figure 8. Nearly half of districts identify students in six or more grades, but more than one-third of districts screen in only one or two grades.

Elementary and middle school programs

Once students are identified as advanced learners, the what of advanced education is extremely variable, ranging from nothing more than asking teachers to differentiate their instruction to providing completely separate schools for advanced students. This section describes what services districts offer for advanced learners in elementary and middle school. Except where noted, the analysis is limited to the 89 percent of districts that reported offering some kind of gifted or advanced program in grades K through 8 (see Figure 1).

Program type

Finding 3: Advanced programming in most elementary and middle schools is limited and of questionable value.

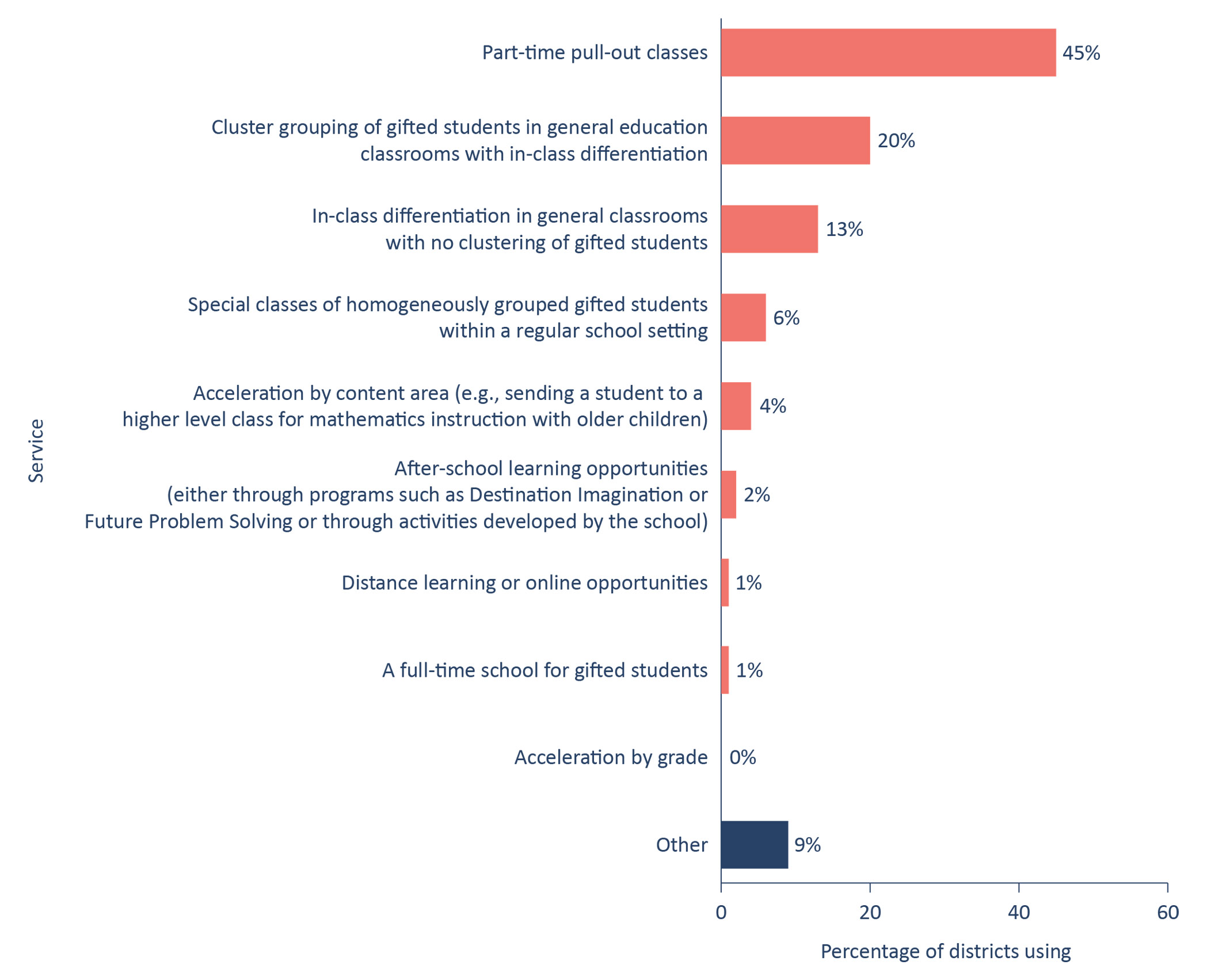

The predominant method of service delivery for advanced learners in elementary schools is, by far, part-time pull-out classes, at 45 percent (Figure 9). The “highest-dosage” programs—special classes for advanced learners and full-time schools for gifted students—are rare (6 percent and 1 percent, respectively). Much more common than high-dosage programs are service delivery methods that require no extra programming at all: cluster grouping in general education classrooms (20 percent) and in-class differentiation with no clustering (13 percent).

Figure 9. The most common type of program that districts report for elementary students is part-time pull-out classes.

Most districts offer multiple services for advanced learners across elementary and middle school, including part-time pull-out classes and cluster grouping of gifted students (Figure 10). One popular high-dose offering is acceleration by content area, available in about half of districts. On the other hand, just 29 percent of districts offer grade acceleration, 28 percent offer special classes for advanced learners, and only 4 percent offer a full-time school for them.

Figure 10. The most commonly offered types of advanced programming in elementary and middle schools are part-time pull-out classes, cluster grouping in general education classrooms, and acceleration by content area.

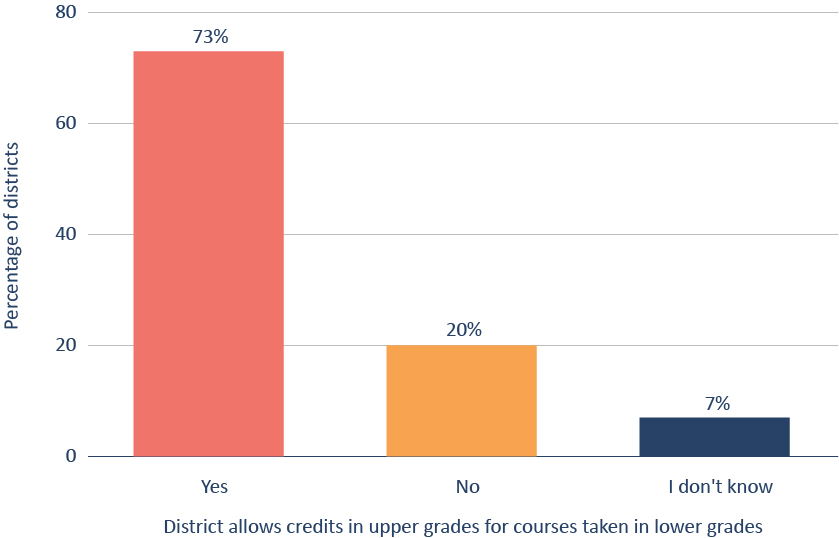

One particularly popular policy is “concurrent enrollment,” wherein students who complete an advanced course in a lower grade can receive credit for it in an upper grade (such as a middle school student earning credit for a high school course). Among the districts, 73 percent reported that such credit transfers are allowed under some circumstances (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Most districts allow students who take an advanced course in a lower grade to receive credit for it in an upper grade.

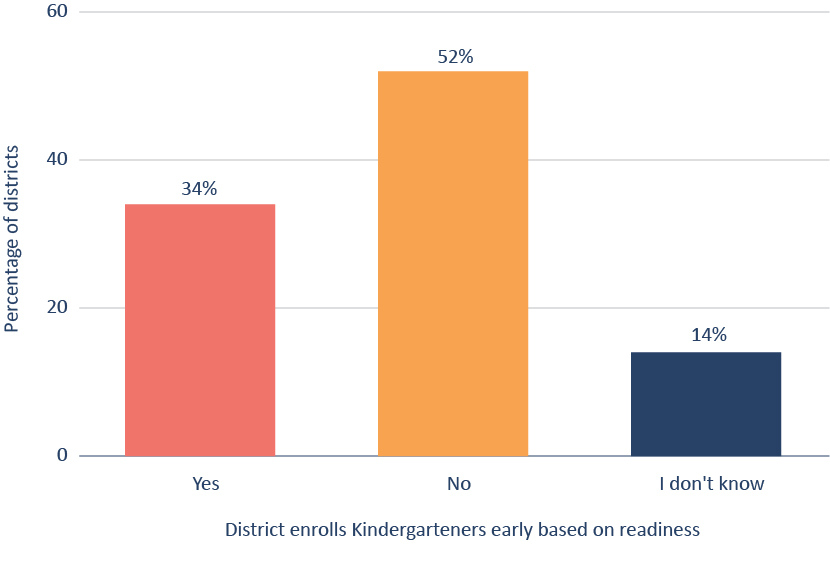

An early form of grade acceleration is to allow children who do not meet the date cutoff for kindergarten to enroll early if they are ready, both cognitively and socially. Yet Figure 12 shows that only about one-third of districts allow early enrollment into kindergarten based on a child’s readiness.

Figure 12. Most districts do not allow early entry into kindergarten based on readiness.

Curriculum

Although it is beyond the scope of this report to evaluate the quality of district curricula, the responses from districts indicate that it is rare to have a pre-designed curriculum for advanced learners (Figure 13). Instead, the most common option, found in 44 percent of districts, is for teachers to use their existing curriculum but differentiate it for advanced learners.

Figure 13. It is most common for districts to use the same curriculum for advanced students that they use for other students, with some modification.

Teachers

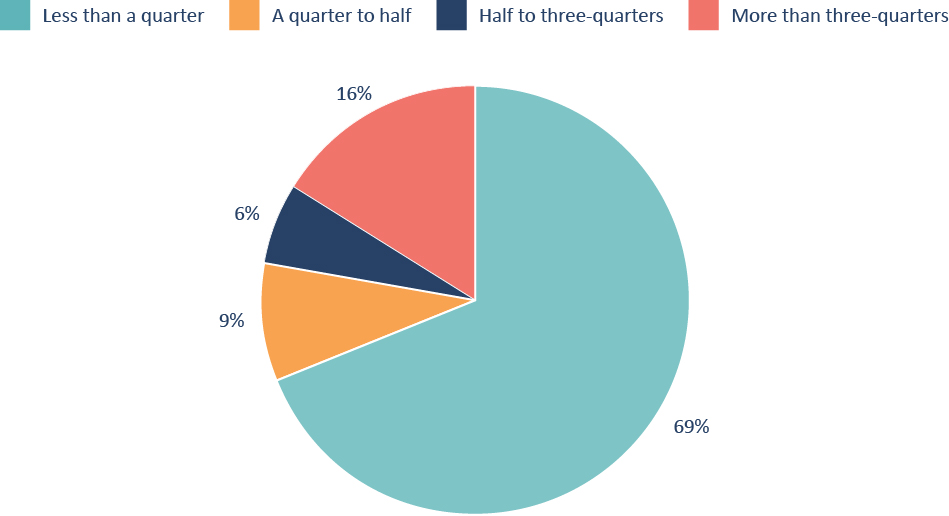

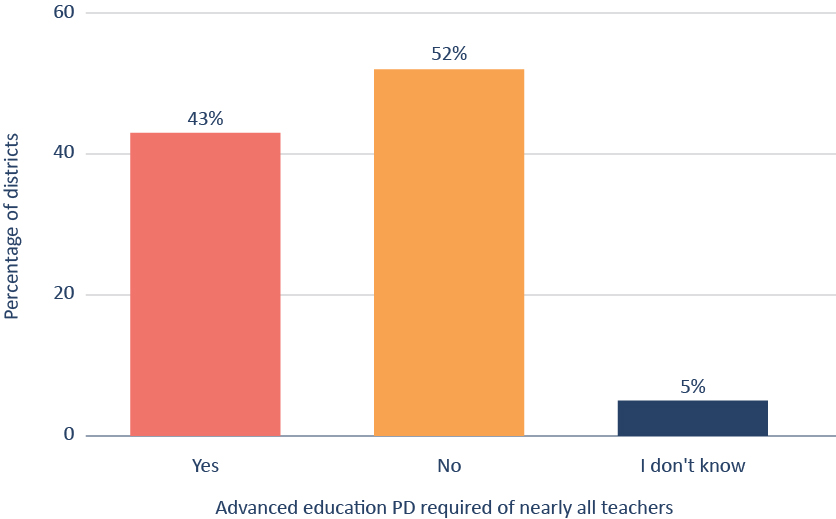

Among districts with K–8 programs for advanced learners, most reported that few teachers hold credentials in advanced education (Figure 14). For instance, sixty-nine percent of districts report that less than a quarter of teachers in the district have credentials in advanced education. Fewer than half of districts require regular professional development on advanced learning strategies (Figure 15).

Figure 14. More than two-thirds of districts with advanced programs report that less than a quarter of their teachers have an endorsement or credential in gifted or advanced education.

Figure 15. Over half of districts with advanced programs report that they do not require most teachers to participate in professional development on advanced learning strategies at least once every two years.

Advanced opportunities in high school

Advanced education works differently in high school, where students sometimes have already specialized in a topic or have the option to challenge themselves with specific courses, programs, and pathways. Likewise, “acceleration” is a less relevant policy, because content is typically organized by courses instead of grade levels. This section describes what services districts offer for advanced learners in high school, with the caveat that these services may not be available in all of a district’s high schools, and some schools may not offer them until the junior or senior year. The analysis includes all district responses, whether or not the district has advanced programs in grades K–8.

Honors

Finding 4: Most high schools offer substantial advanced programming, although students may lack access if they do not meet the prerequisites.

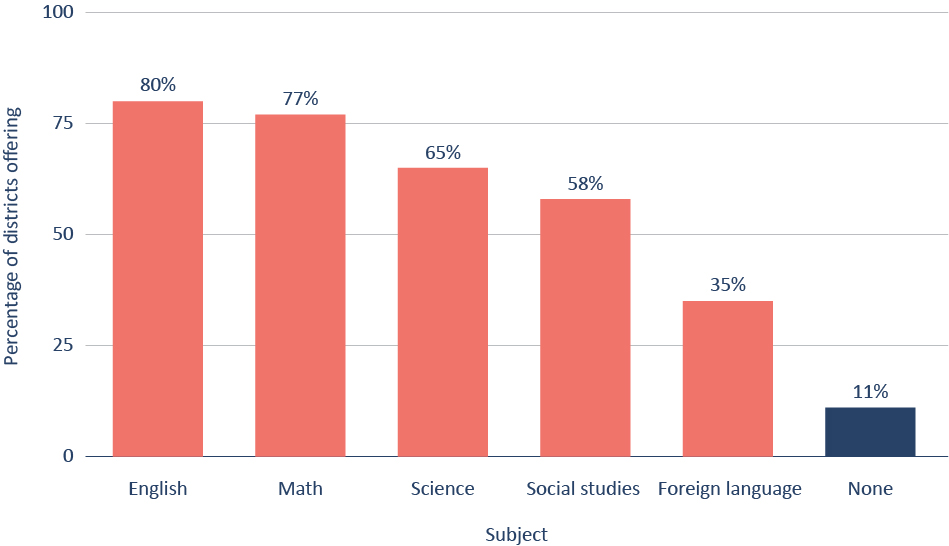

Courses that are designated as “honors” (or something similar) are widespread; only 11 percent of districts reported offering no such courses (Figure 16). The most commonly offered honors courses are in the universal subjects of English (80 percent) and math (77 percent).

Figure 16. The most common honors courses offered in high school are English and math, while 11 percent of districts offer no honors courses.

Advanced Placement

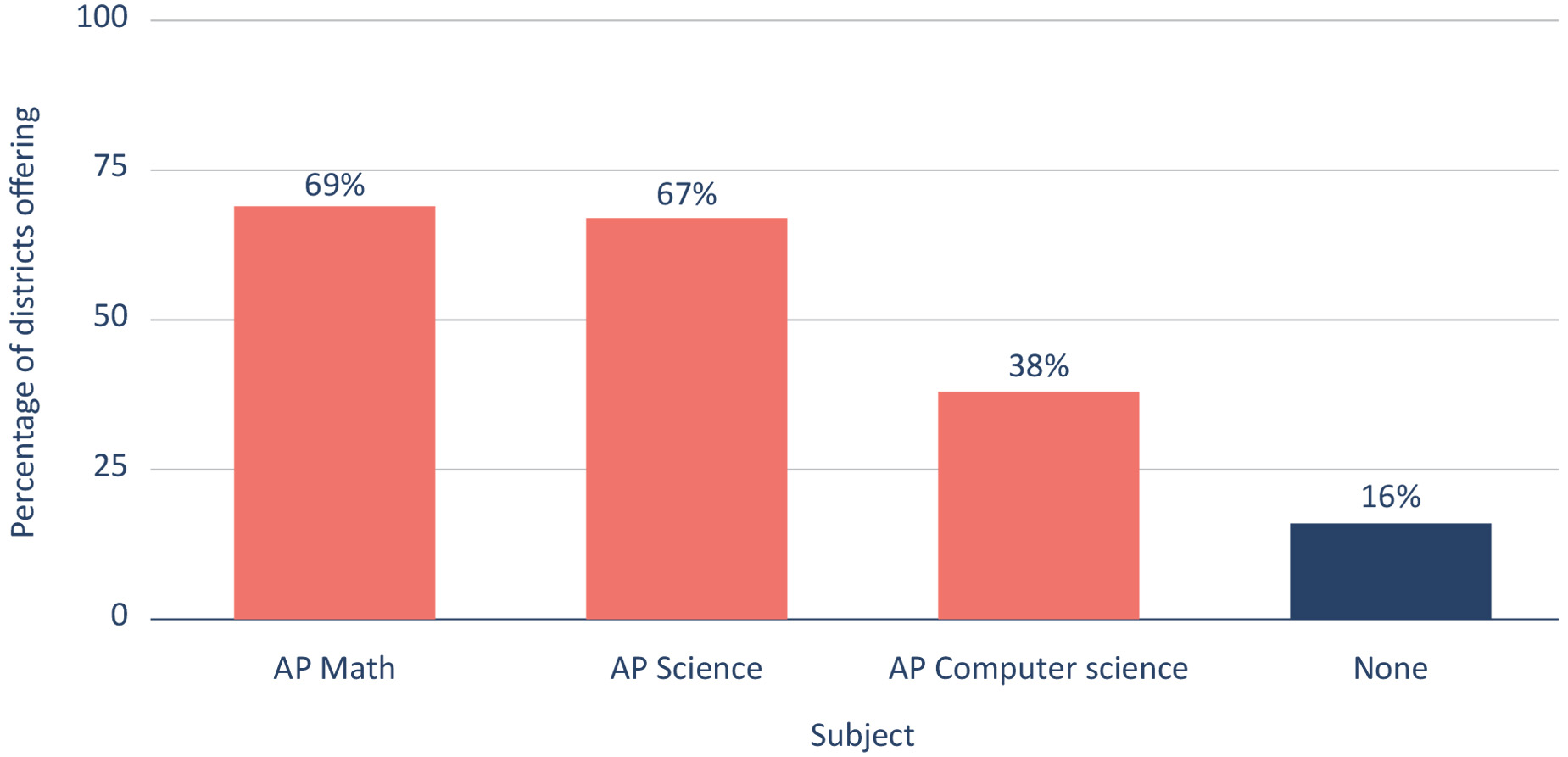

The Advanced Placement (AP) program is central to advanced course offerings in American high schools. Figure 17 shows that most districts have students participating in AP; just 16 percent reported having no students enrolled in any AP courses. Only math, science, and computer science are disaggregated in OCR’s 2020–21 AP data collection, and the first two are most commonly offered. Again, as is the case with other programs, there is often significant variation among offerings across high schools within districts.

Figure 17. Just 16 percent of districts have no students enrolled in AP.

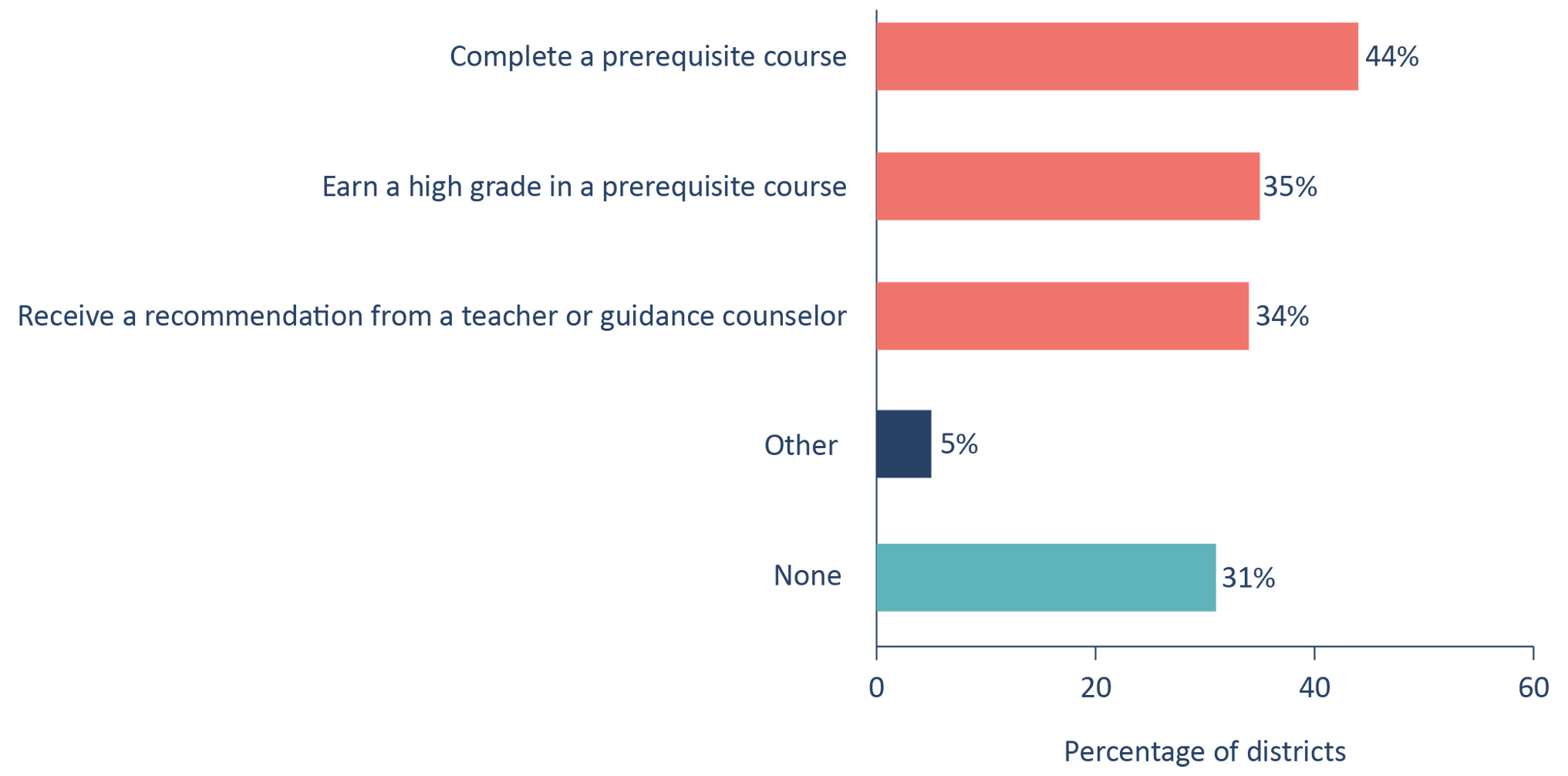

Although AP courses are common in America’s school districts, access to them is regulated in most districts: Just 31 percent of districts make these courses “open access,” with no prerequisite courses, grades, or recommendations (Figure 18). The most common requirement for AP enrollment is completing a prerequisite course (44 percent), while earning a high grade in the prerequisite course (35 percent) and receiving a recommendation from school staff (34 percent) are also relatively common.

Figure 18. Less than one-third of districts have no prerequisites for Advanced Placement enrollment.

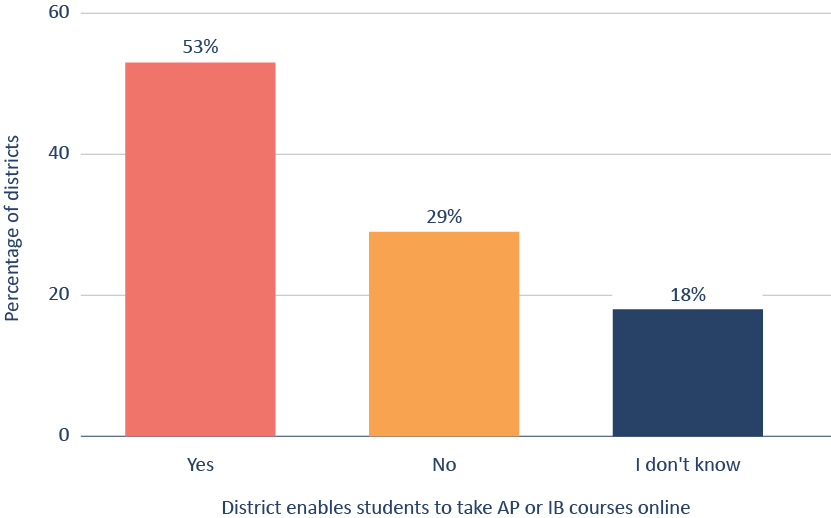

Among districts that do not directly offer specific advanced high school courses, about half allow students to access AP and International Baccalaureate (IB) courses through online offerings (Figure 19).

Figure 19. About half of districts expand the opportunity to take advanced courses by allowing students to take AP or IB courses online.

What predicts comprehensive policies for advanced learners?

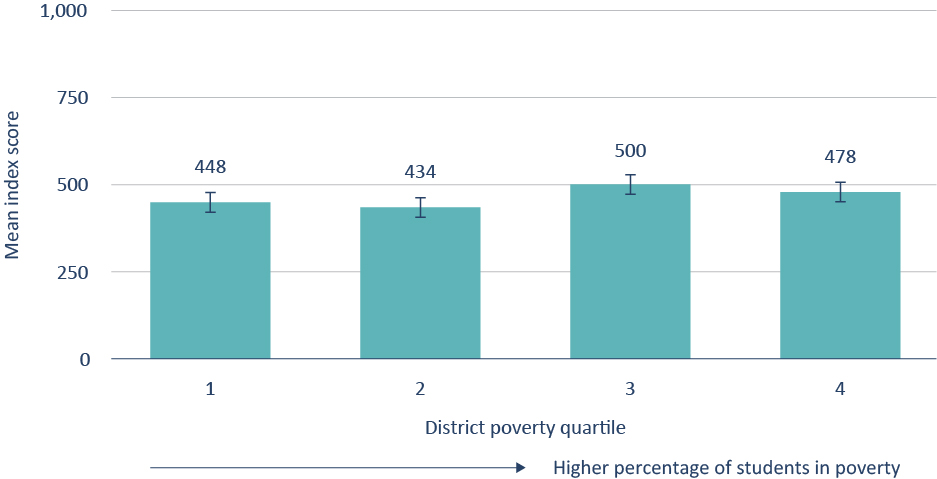

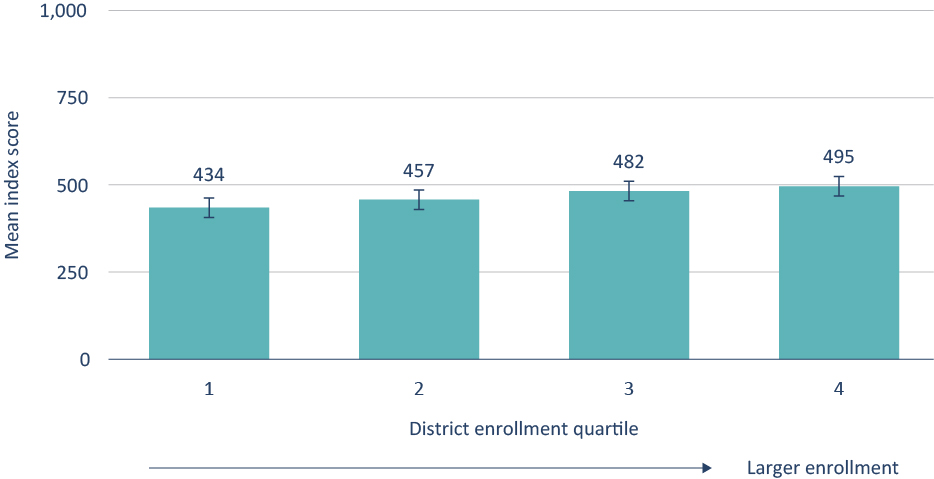

None of the key demographic variables examined, including district size, district poverty, and racial makeup, are good predictors of comprehensive district policies for advanced learners, measured using the Advanced Education Index Score (see “How comprehensive are district policies?”). For an analysis by district racial composition, see Appendix B.

Finding 5: District demographics are not good predictors of district policies.

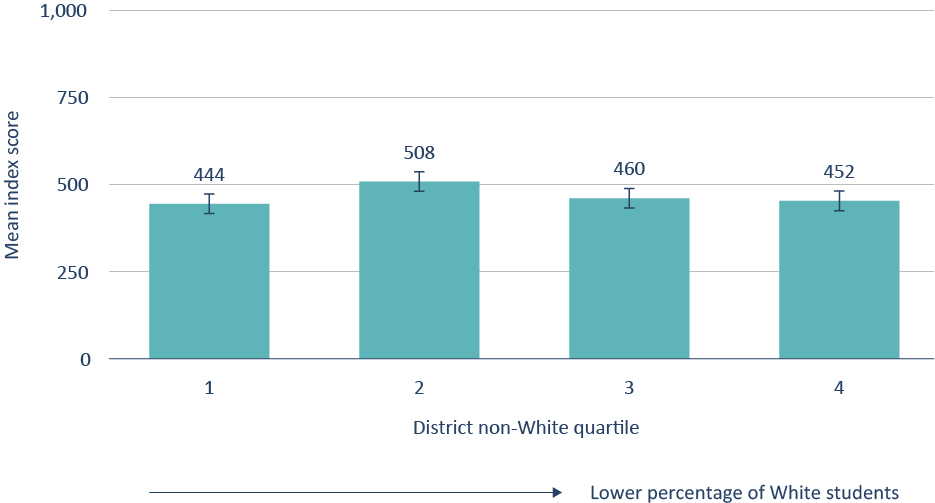

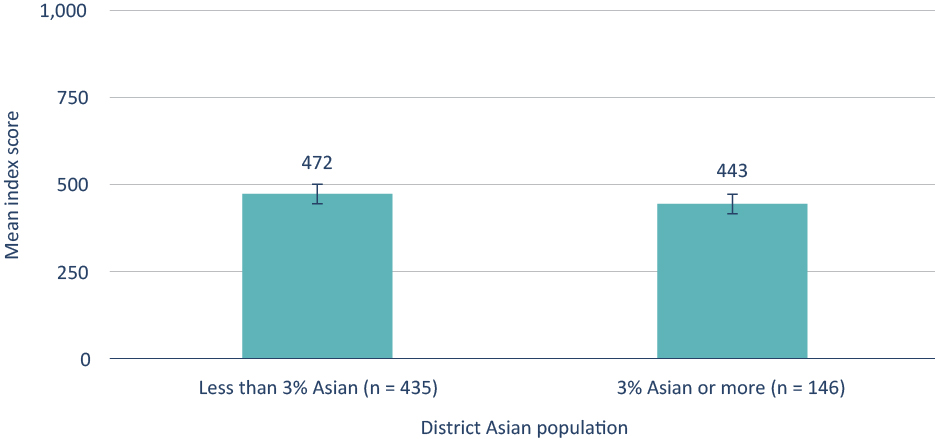

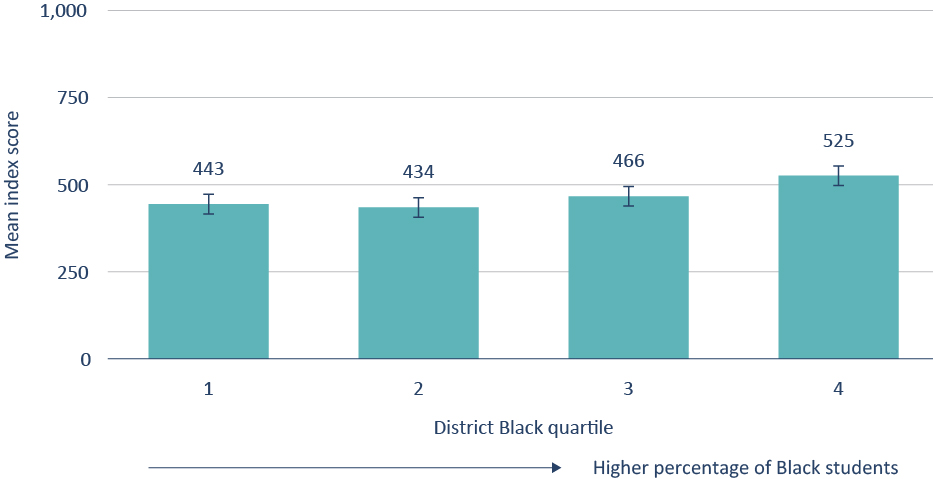

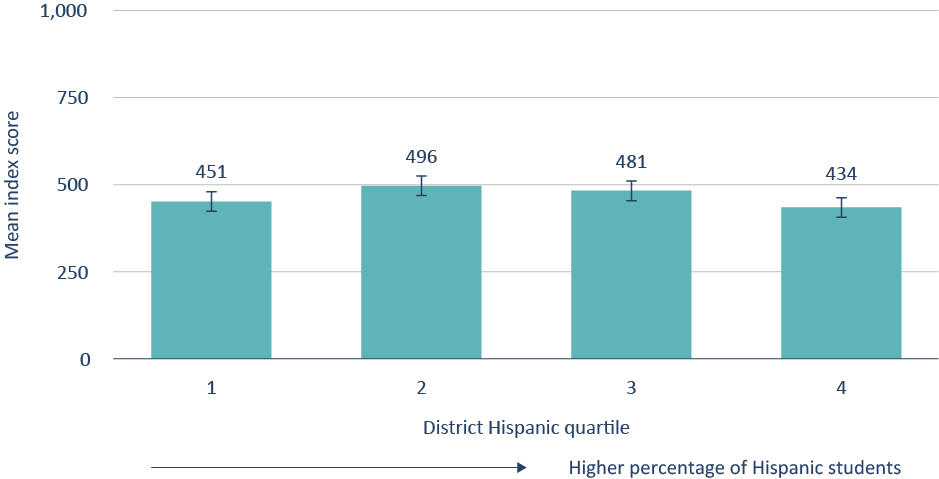

There are no statistically significant differences in the comprehensiveness of district policies by a district’s rate of poverty (Figure 20), size (Figure 21), or racial/ethnic makeup (Figure 22), although larger districts may have slightly more comprehensive policies. This pattern holds for other racial/ethnic groups as well (see Appendix B, Figure B1, Figure B2, and Figure B3).

Figure 20. There is no significant difference in the comprehensiveness of gifted programs by the rate of poverty among students.

Figure 21. Larger districts may have somewhat more comprehensive policies, but the differences are not statistically significant.

Figure 22. There is no significant difference in the comprehensiveness of gifted programs by the racial makeup of the district.

Policy implications

This analysis raises four key policy implications.

First, districts can improve access to and the substance of advanced education by adding stronger policies to their existing repertoire. Given the mediocrity of advanced education policies writ large, there is significant work to be done when it comes to getting school districts to adopt best practices in advanced education. From identification to programming to teacher supports, most districts eschew many optimal policies. For advanced education programming in elementary and middle school, some districts report that the only way they serve the needs of advanced students is through teacher differentiation within classrooms. Yet teachers also admit that differentiating instruction to a wide range of achievement levels is challenging, and there is research suggesting that educators do not see advanced students as the ones who need differentiation.[16] Instead, districts should offer more intensive advanced programming, including broadening acceleration, while also using more inclusive means of identifying students, such as incorporating local norms in identification.

Second, districts should build on the growing popularity of universal screening to expand the number of “on ramps” to advanced education in a larger number of grades. It is heartening that some form of universal screening for advanced programs has become so pervasive, since it is a proven way to make advanced programming more equitable while maintaining rigorous academic standards. In many districts, however, screening is only occurring in one or two grades. One way to add more “on ramps” is to flag advanced potential using students’ scores on state end-of-grade assessments, which are already universal in most grades and which researchers have shown can broaden the pool of advanced students.[17]

Third, districts should use local norms (based on where each student falls in the school or district distribution of scores) to identify students for advanced education services, with the goal of identifying at least 5 to 10 percent of them in each school. The survey results show that many unnecessarily restrictive identification policies are widespread. Early enrollment to kindergarten, for example, is quite rare. Even worse, to identify students for advanced education services, most districts focus on national norms (e.g., the 95th percentile of the national student distribution), which can be both restrictive and unresponsive to the needs of socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. Although it is debatable, for instance, whether high school AP courses ought to have some prerequisites, policies that limit opportunities for advanced education programs to a tiny sliver of the student population needlessly block access. Broadening access, particularly in elementary and middle school, not only helps more students who can benefit from greater challenge, but disproportionately expands opportunities for students from low-income communities and students experiencing other disadvantages.

Finally, the field of advanced education needs reformers who focus on the content and substance of these programs. In recent years, reformers have focused largely on identification practices for advanced education, and we appear to be making progress there. Yet advanced programming must be more than simply asking teachers to differentiate their instruction; it must also include substantive, challenging programming for students. Unfortunately, less than one in six districts uses full-time classes, a dedicated school, or subject or grade acceleration as the primary means of delivering advanced education programming in the early grades. At the same time, nearly half of districts use the same curricula for advanced learners as for other students. Considering how high-quality research on advanced education identification policies has challenged and changed this field, researchers need to investigate new ways of identifying the impact of these different means of delivering advanced education services to students.

Appendices

- Acceleration, according to the National Association for Gifted Children, “occurs when students move through traditional curriculum at rates faster than is typical.” Students can be accelerated by completing advanced material or coursework in a single subject or by skipping an entire grade.

- The umbrella term “advanced education” refers to all educational practices that serve advanced learners in K–12, such as “gifted” programs, selective schools, and the Advanced Placement (AP) program.

- An advanced education credential is a specialized certification or degree that indicates that an educator has received specialized training in working with advanced learners.

- The Advanced Education Index, presented in Table 1 of this report, shows the point values assigned to districts’ advanced education policies. Policies deemed most critical by the National Working Group on Advanced Education earn the most points; policies that are relevant but less critical receive fewer points. As a result, districts with the strongest set of advanced education policies earn the most points.

- Advanced enrichment programs develop advanced learners’ interests, skills, and knowledge outside the classroom.

- Advanced Placement (AP) courses are college-level courses offered to high school students by the College Board. Students who achieve high scores on the final AP exam can receive college credit. There are 38 such subject exams.

- Cluster grouping occurs when a teacher creates a small group of advanced learners within an otherwise heterogeneous class. The small group, or cluster, receives specialized instruction.

- With concurrent enrollment, often known as dual enrollment, a student takes a course typically offered at a higher level, such as a middle school student taking a high school–level foreign language course or a high school student taking a college-level history course. With the single course, the student can simultaneously earn credit for both the current grade level and the level at which the course is typically taken.

- Teachers implement differentiated instruction when they design lessons, activities, and/or assignments in ways that are tailored to individual students’ needs. Differentiation can occur with or without cluster grouping.

- A distinct advanced curriculum is a curriculum that is specifically designed to meet advanced learners’ needs, as opposed to a standard curriculum that teachers can differentiate for students at different skill levels.

- Full-time advanced schools serve only advanced learners. In these settings, advanced learners do not receive specialized instruction in a standard classroom or take accelerated courses in a typical school; rather, the entire school is dedicated to meeting advanced learners’ needs.

- General education settings are those that serve the typical educational needs of most students; that is, general education is not designed to serve either advanced learners or students with significant disabilities.

- “Gifted education” is another term for “advanced education,” but is typically limited to the elementary and middle school context.

- Honors classes, often offered in middle and high school, offer a greater challenge to students in particular subject areas. These classes tend to be more rigorous in terms of content and expectations.

- “Identification,” often used interchangeably with “screening,” refers to the process by which educators and administrators determine which students qualify for certain types of programming, such as gifted programs or accelerated classes.

- Indicators are tools that educators and administrators use to identify students who may qualify for specialized programming. For example, a district may base admission to an advanced education program on indicators such as standardized test scores, teacher referrals, or student portfolios.

- International Baccalaureate (IB) courses are college-level courses offered to high school students in 160 countries, including the United States. As with AP, students can receive college credit if they earn high scores on their IB assessments. IB courses, however, are international. There are 57 IB courses, and students can pursue either Standard Level (SL) or High Level (HL) options.

- Administrators use local norms for identification when they screen students for specialized programming based on the academic performance of “local” peers—that is, they compare students’ performance with that of peers within the same district or school—rather than statewide or national performance.

- In pull-out programs, students receiving special services are literally “pulled out” of the general education classroom to receive specialized instruction. Another teacher, such as a gifted specialist, works with these students in another space in the building for a designated period during the school day.

- “Services,” often used interchangeably with “programs,” refers to any aspects of specialized education that a student receives due to special qualifications. Services may include, for example, pull-out programs or access to accelerated coursework (see above).

- Universal screening occurs when educators and administrators screen all students for special abilities in a standardized way, thereby expanding the pool of potential candidates.

Appendix B: Demographic predictors of advanced education policies

This section provides additional figures and analysis relative to race and ethnicity.

Figure B1. There is no significant difference in the quality of gifted programs by the percentage of Asian students in the district.

Figure B2. There is no significant difference in the quality of gifted programs by the percentage of Black students in the district.

Figure B3. There is no significant difference in the quality of gifted programs by the percentage of Hispanic students in the district.

Appendix C: Index Scores and Recommendations

Table C1. Advanced Education Index scores are tied to specific recommendations from the National Working Group (NWG) on Advanced Education.

*The survey was not able to capture this recommendation about instructional practices, but the Index does include a question about teacher credentials, which may indicate stronger teacher preparation for instructing advanced learners.

Appendix D: Comparisons to Earlier Survey

This section shows differences in the results of the present survey compared to similarly worded questions on a 2013 survey conducted by researchers at the University of Virginia.[18] Because of the variation in how the surveys were administered and analyzed, we urge caution in interpreting any differences in the results.

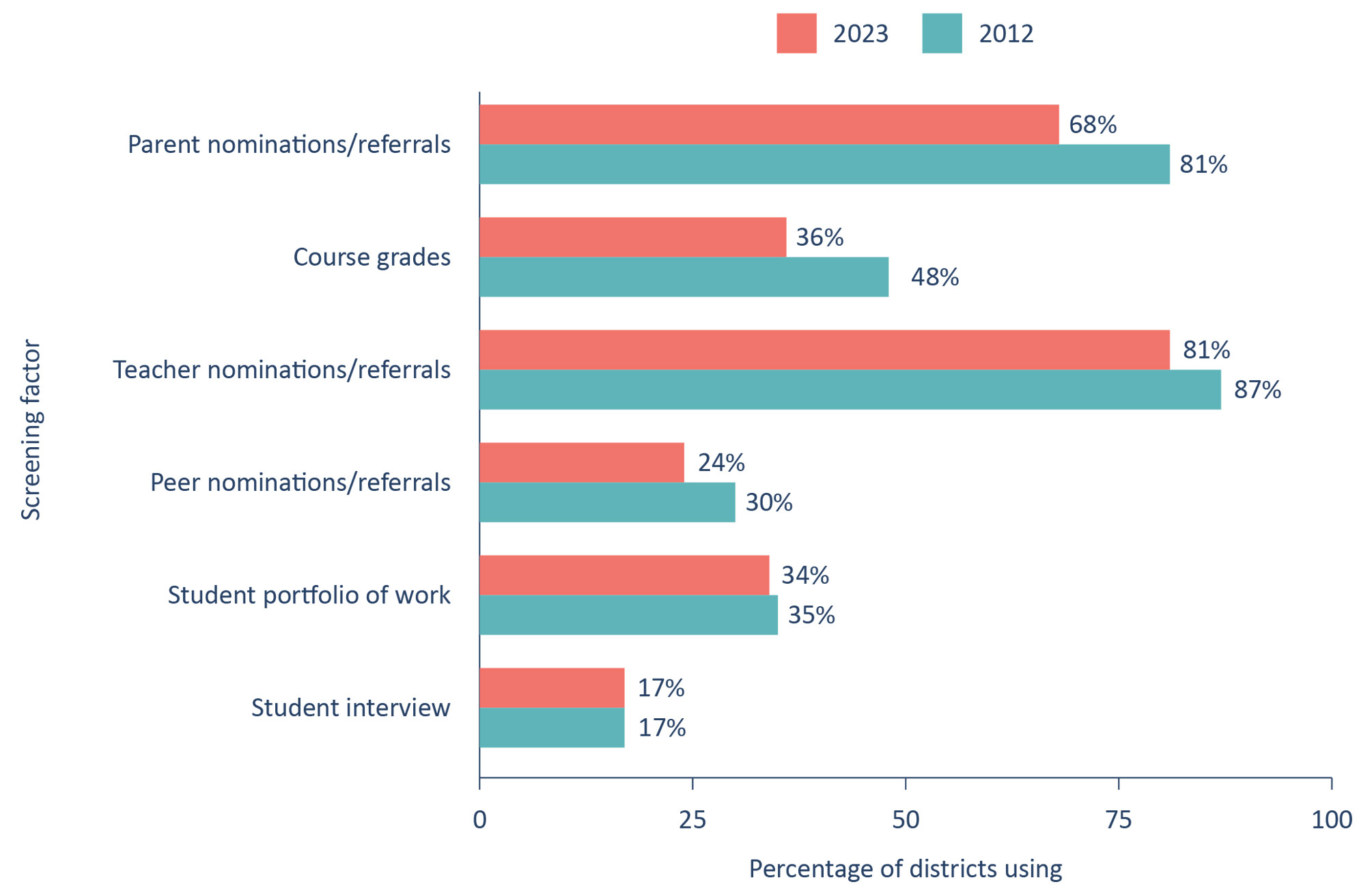

Figure D1 shows the proportion of districts that use common methods for screening students for advanced education programming. The popularity of these screening methods is similar across the two surveys, and the rank order of the factors is identical (i.e., teacher referrals are the most common, student interviews are the least common, etc.). Still, the prevalence of parent referrals and grades as screening methods seems to have declined somewhat during the period between the studies.

Figure D1. The proportion of districts using common screening factors remained stable from 2012 to 2023, although parent referrals and course grades may have declined somewhat in popularity.

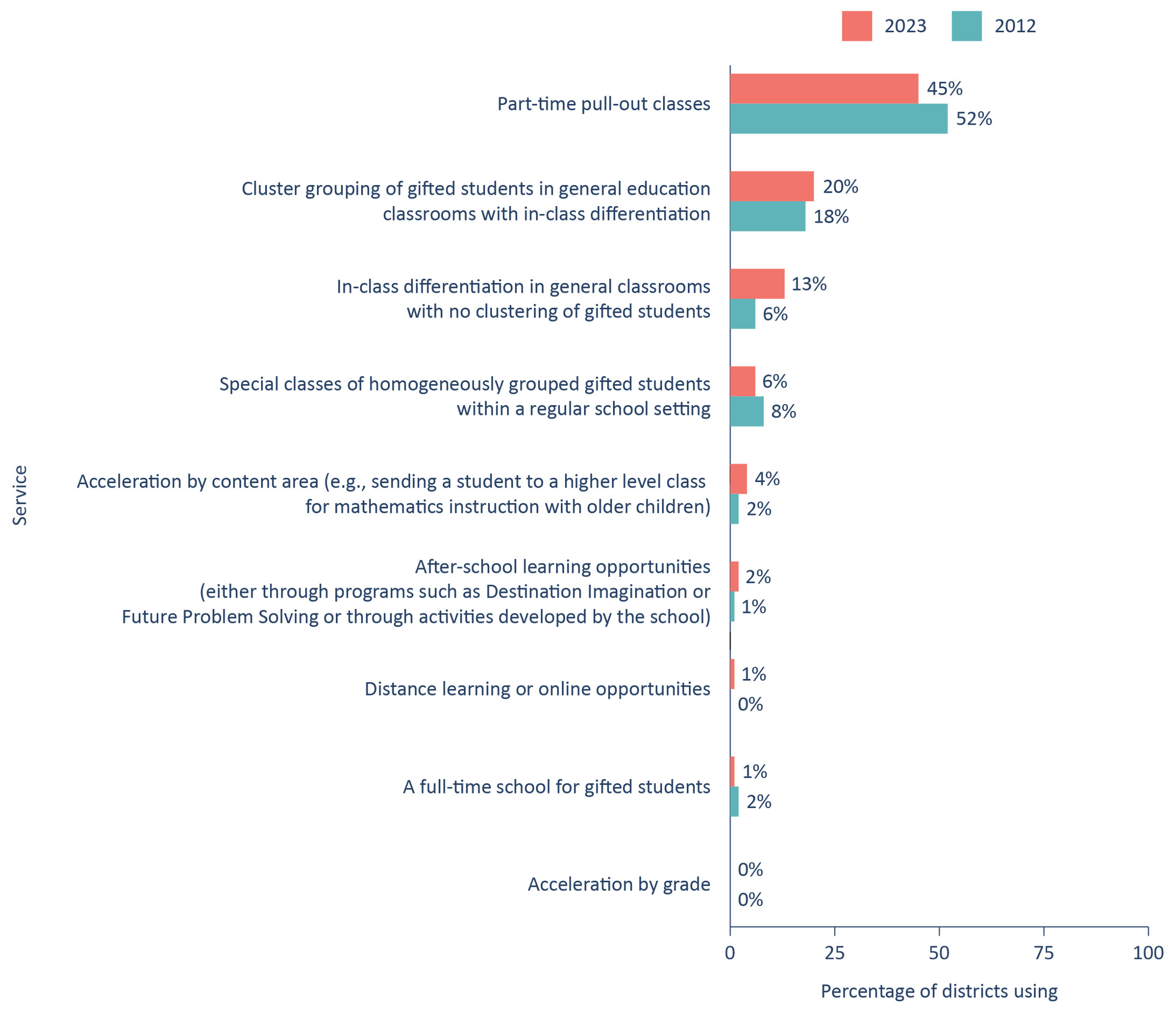

As with screening factors, the prevalence of different types of advanced programming appears to be mostly stable across the surveys, and the rank order is similar (e.g., part-time pull-out classes are the most popular in both). Worryingly, the lowest-impact delivery mechanism, in-class differentiation with no clustering, may have increased during the period between the surveys: Our 2023 survey shows that it was the primary type of programming in 13 percent of districts, while the comparable figure in the 2012 survey was just 6 percent.

Figure D2. The prevalence of types of advanced programming has remained stable in recent years, although there may be an increase in differentiation without clustering and a decrease in part-time pull-out classes.

Endnotes

[1] This report uses the term “advanced” to describe programs for high-performing or high-ability students. Traditionally, the term “gifted” has been used to describe many of these programs, but “advanced” better captures the fact that these programs are meant to serve not just students with exceptional inborn ability but any students capable of handling significantly greater than typical challenges. “Advanced” also covers a broader range of programs throughout K–12 education, including honors programs and AP courses, whereas “gifted” programs are typically confined to the early grades.

[2] “Building a Wider, More Diverse Pipeline of Advanced Learners: Final Report of the National Working Group on Advanced Education,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (June 2023). https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/building-wider-more-diverse-pipeline-advanced-learners.

[3] David Card and Laura Giuliano, “Universal screening increases the representation of low-income and minority students in gifted education,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, no. 48 (2016): 13678–83. https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.1605043113.

[4] Scott J. Peters, Karen Rambo-Hernandez, Matthew C. Makel, Michael S. Matthews, and Jonathan A. Plucker, “Effect of local norms on racial and ethnic representation in gifted education,” AERA Open 5, no. 2 (2019): 2332858419848446. Illinois Association for Gifted Children, “The Accelerated Placement Act.” https://www.iagcgifted.org/IL-Acceleration-Act, accessed April 20, 2023. Karen B. Rogers, “The Academic, Socialization, and Psychological Effects of Acceleration: Research Synthesis,” in A Nation Empowered: Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America's Brightest Students, Volume 2, Susan G. Assouline, Nicholas Colangelo, Joyce VanTassel-Baska, and Ann Lupkowski-Shoplik, eds. (Cedar Rapids, IA: Colorweb Printing, 2015). https://ncrge.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/982/2022/12/ch2-A-Nation-Empowered-Vol2-2.pdf.

[5] David Card and Laura Giuliano, “Can tracking raise the test scores of high-ability minority students?” American Economic Review 106, no. 10 (2016): 2783–816.https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20150484.

[6] Carolyn M. Callahan, Tonya R. Moon, and Sarah Oh, “Status of Gifted Programs,” National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, University of Virginia Curry School of Education, Charlottesville, VA (2013).

[7] “Gifted Education: Results of a National Survey,” EdWeek Research Center (November 2019). https://www.edweek.org/research-center/research-center-reports/gifted-education-results-of-a-national-survey.

[8] Scott J. Peters and James S. Carter III, “Predictors of Access to Gifted Education: What Makes for a Successful School?” Exceptional Children 88, no. 4 (2022): 341–358.

[9] Christopher B. Yaluma and Adam Tyner, “Is there a gifted gap? Gifted education in high-poverty schools.” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (2018). https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/there-gifted-gap-gifted-education-high-poverty-schools

[10] Christopher B. Yaluma and Adam Tyner, “Are US schools closing the ‘gifted gap’? Analyzing elementary and middle schools’ gifted participation and representation trends (2012–2016),” Journal of Advanced Academics 32, no. 1 (2021): 28–53.

[11] Throughout the report, “district” is used to denote these entities, although some are local education agencies (LEAs) that represent groups of charter schools. Although there are about 14,000 school districts and charter school networks in the U.S., most of these are very small and educate very few students. The LEAs included in our sample frame (from which we selected districts randomly) each enroll at least 1,534 students. The remaining LEAs for which grade span data are available in the 2020–21 NCES Common Core of Data collectively serve just 10 percent of the K–12 student population and were excluded from the sample frame.

[12] Callahan et al.

[13] Respondents were offered a gift card for Amazon or Starbucks.

[14] Overall, of the 3,659 randomly selected districts that were contacted, 581 responded, yielding a response rate of 15.9 percent. Post-stratification weighting allows the reported values throughout this study to approximate the results from the sample frame.

[15] “Building a Wider, More Diverse Pipeline.” For specifics about how questions align with recommendations by the National Working Group, see Table C1 in Appendix C.

[16] K. L. Westberg, F. X. Archambault, S. M. Dobyns, & T. J. Salvin (1993). “An observational study of instructional and curricular practices used with gifted and talented students in regular classrooms.” Storrs, CT: National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED379846.pdf.

[17] Bich Thi Ngoc Tran, Jonathan Wai, Sarah McKenzie, Jonathan Mills, and Dustin Seaton. "Expanding gifted identification to capture academically advanced, low-income, or other disadvantaged students: The case of Arkansas." Journal for the Education of the Gifted 45, no. 1 (2022): 64-83.

[18] Callahan et al.

About this Study

A number of individuals deserve credit for helping us develop and execute the survey, including the members of the National Working Group on Advanced Education, which discussed this survey project at a meeting in 2022. We especially appreciate the input of Scott Peters, who gave feedback on the survey sampling methodology, and Jennifer Glynn and Karen Rambo- Hernandez, who offered insightful feedback on the draft report. Early thinking about the survey design was also enriched by conversations with classroom teachers Daniel Buck and Erica Clark. In addition to other experts, several individuals piloted the survey and engaged in discussions with Fordham staff about its design (including Stephanie Knox, Kristen Modes and Dina Brulles). We also greatly appreciate the assistance of several state coordinators (especially North Carolina's Sneha Shah-Coltrane) for advanced education who helped us reach districts in our sample. Thanks as well to Dave Williams for helping design the figures in the report.

At Fordham, we thank Adam Tyner for directing the survey research, conducting the analysis, and authoring the report; Chester E. Finn, Jr., Michael J. Petrilli, and Amber Northern for providing feedback on the draft instrument and draft report; Stephanie Distler for managing report production and design; Jeanette Luna for assisting with grant administration; Daniel Buck, Nathaniel Grossman, Josh Einis, and Meredith Coffey for assisting with background research; Brandon Wright for help with copy editing; Jeff Murray, Kate Kerin, and Abigail Hamilton for reaching out to potential respondents; and Victoria McDougald for overseeing media dissemination.