This is fourth in a series in which I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget. Previous pieces covered the science of reading as well as funding for low-income pupils and interdistrict open enrollment. This essay looks at guarantees.

One of the most vexing problems in school finance is reliance upon provisions that shelter districts from funding reductions. At first blush, these provisions—known as “guarantees”—don’t sound so bad, and cutting funding is never politically appealing, no matter the circumstance. But school districts do change and sometimes do so in ways that should reduce their need for state aid. Districts that are losing enrollment have fewer expenses and thus require less funding. Meanwhile, those with increasing local wealth they can tap into should have less need for state assistance, too.

A well-functioning state funding formula would adjust district allocations for those types of changes. But guarantees circumvent the formula, providing excess funds above and beyond formula prescriptions to ensure a district’s funding doesn’t fall below some historical level. This is problematic on both fairness and efficiency grounds. In terms of fairness, guarantees amount to special handouts given only to certain districts, a “pork barrel”–type method of allocating dollars that can end up shortchanging districts more in need of state aid. They also treat parents and students unfairly, as they weaken districts’ incentives to serve them well in an effort to keep them as “customers.” If no funding is lost when parents and students head for the exits, schools have fewer incentives to improve. As for efficiency—a school funding concept enshrined in the Ohio Constitution—guarantees promote fiscal largesse, as districts can avoid trimming budgets to account for smaller enrollments. They also represent a poor use of taxpayer dollars, as they send funds to educate what are in effect “phantom students.”

Despite these problems and some attempts to root them out, Ohio has long embedded guarantees into its funding system. The Kasich administration used to prod the legislature to address guarantees, as have we at Fordham. More recently, the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan seemed to promise their demise, too. In their advocacy push a few years ago, plan proponents attacked Ohio’s old funding system as a “patchwork” whereby hundreds of districts were funded via guarantees while others were “capped.” Instead, they pledged a model that “bases state school funding on actual student need … and treats all Ohio school districts and taxpayers fairly, based on capacity to pay.” In other words, supporters claimed that this plan would finally move the state toward a system in which the formula is scrupulously followed. An early projection from advocates suggested that the plan would immediately cut the number of districts on the guarantee from roughly half to just one-sixth, and one school group official predicted that, over time, “a need for a guarantee should go away.”

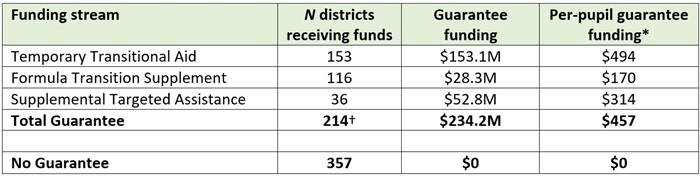

The Cupp-Patterson model—now billed the “Fair School Funding Plan”—was enacted in 2021, and the third year of implementation (fiscal year 2024) is drawing to a close. Yet Ohio’s funding system still includes guarantees that protect hundreds of districts from funding reductions otherwise prescribed by the formula. While some progress has been made in removing districts from the guarantee, 35 percent remained on one as of FY24. That’s not fast enough progress, especially given the pledges made by the Cupp-Patterson advocates. Three funding streams in particular comprise the guarantee given to certain districts this year:[1]

- Temporary Transitional Aid: Guarantees that districts do not receive less state funding than in FY20.

- Formula Transition Supplement: Guarantees that districts do not receive less state funding than in FY21.

- Supplemental Targeted Assistance: Provides certain districts extra dollars based on their FY19 enrollments. This funding stream functions like a guarantee by providing a special subsidy for districts that historically lost enrollments as students chose charter and private-school options.

Taken together, these items cost the state approximately a quarter-billion dollars this year, or $457 per pupil. While not a huge sum in the context of the state’s entire education budget, this is more than the state is spending on the Science of Reading initiative ($169 million over two years) and above its annual expenditure on career-technical-education categorical funding (roughly $215 million this year).

Table 1: Guarantee funding for Ohio districts, FY2024

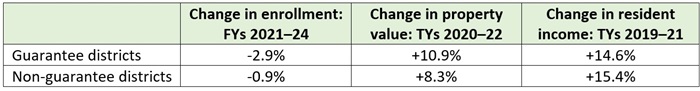

As shown in Table 1, not all districts benefit from the guarantee. And as noted earlier, guarantees tend to subsidize districts that are losing enrollment and/or growing in local wealth, factors that should reduce their need for state assistance. Table 2 shows that the districts on the guarantee have indeed experienced larger enrollment declines in recent years: -2.9 percent versus -0.9 percent for non-guarantee districts from FY21 to FY24. Their property values have also increased at a faster clip than non-guarantee districts, though resident incomes have not.

Table 2: Characteristics of districts on a guarantee

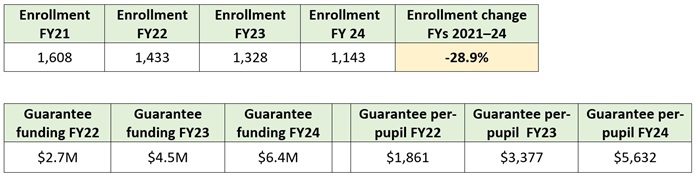

That guarantees can be a crutch for shrinking districts is starkly illustrated by looking at East Cleveland City School District, far and away the biggest beneficiary of the guarantee on a per-pupil basis. In FY24, the district received a staggering $5,632 per pupil in guarantees, an amount that sends the district’s overall state funding to levels that are way out of line with similarly situated districts. For instance, East Cleveland this year received roughly $24,000 per pupil in total state aid, whereas nearby Cleveland Metropolitan School District received a more rational $9,700 per pupil from the state.[2] East Cleveland’s massive guarantee, which it has received in all three years of Cupp-Patterson implementation, shields it from the state funding reductions that would otherwise occur due to its rapidly declining enrollment (-28.9 percent from FY21 to 24).

Table 3: East Cleveland school district enrollment trends and guarantee funding

School funding guarantees are bad public policy. They undermine the principles of a fair and efficient funding system designed to deliver dollars to districts via formula. They misdirect funds to districts that are less in need of state assistance and enable shrinking districts to avoid making necessary budgetary decisions that promote good stewardship of taxpayer funds. In the next budget bill, state legislators should fulfill what the Cupp-Patterson plan initially promised Ohio: a state funding system that treats schools, students, and taxpayers fairly. Removing guarantees from the system—and actually following the formula—would be a big step toward instituting a school funding model that is “fair” in more than name only.

[1] This doesn’t include other guarantee-like mechanisms in the formula, such as the staffing minimums inside the base-cost formula that benefit small districts, or a minimum state share percentage for high-wealth districts.

[2] CMSD was mostly funded via strict formula but received $160 per pupil in supplemental targeted assistance.