The Advanced Placement program is undergoing a radical transformation. Over the last three years, the College Board has “recalibrated” nine of its most popular AP Exams so that approximately 500,000 more AP Exams will earn a 3+ score this year than they would have without recalibration. If this process continues in other exams in the coming years (as I expect it will), approximately 1,000,000 more AP Exams every year will earn a 3+ score. The end result will be a win for AP students everywhere: Millions of high school students will save millions of dollars in college credits in the coming years.

In this article, I’m going to break down the most recent data on this “Great Recalibration”. I’ll also explain why the College Board is changing AP scores and what these changes will mean for AP teachers and students in the coming years.

Breaking down the data

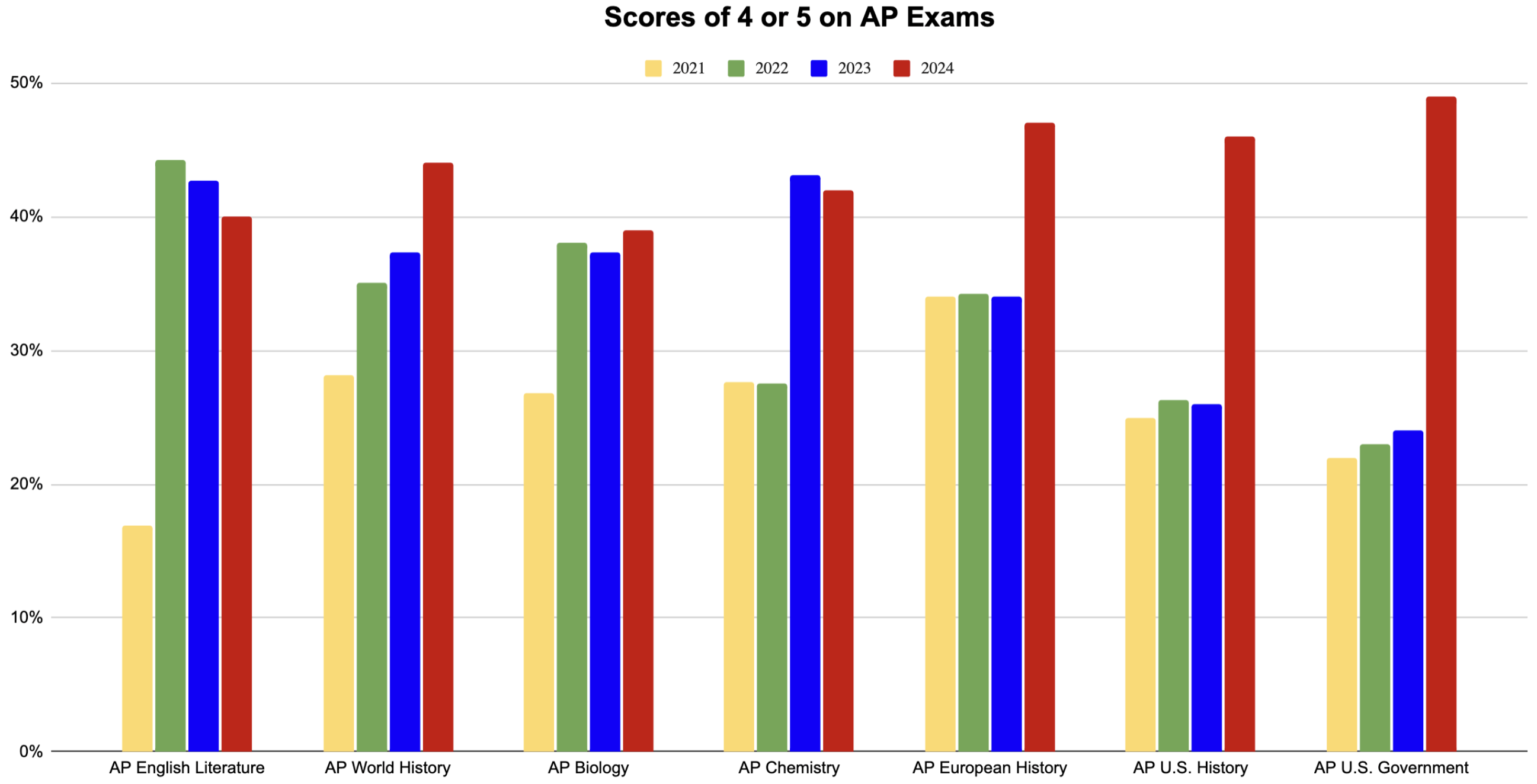

The new score distribution data of AP Exams is astonishing. Beginning with AP English Literature in 2022, a total of nine AP Exams have been “recalibrated” upward so that average scores, the proportion of scores of 3 or above, and the proportion of scores of 4s and 5s, have all increased, while the proportion of scores of 1s and 2s (sometimes referred to as “failing” scores) has decreased. Here is a graph of scores of 4s and 5s for seven of the nine recalibrated AP Exams:

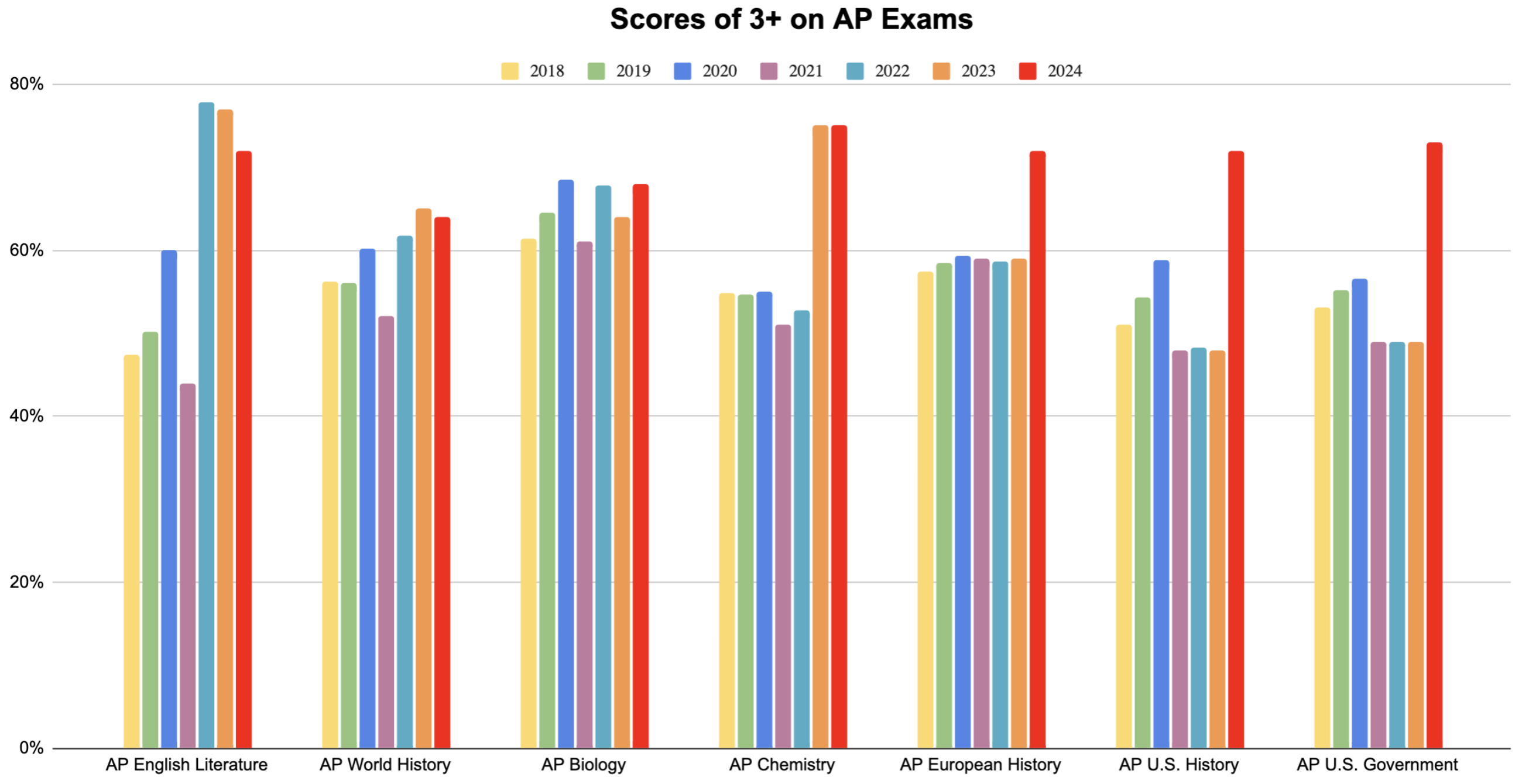

No matter which way you assess the data—means, medians, modes, 3 or above, 4s and 5s, pre-covid, post-covid—the trend is always the same: AP scores are being deliberately and intentionally increased. Here is a more comprehensive graph of scores of 3 or above from 2018 to 2024:

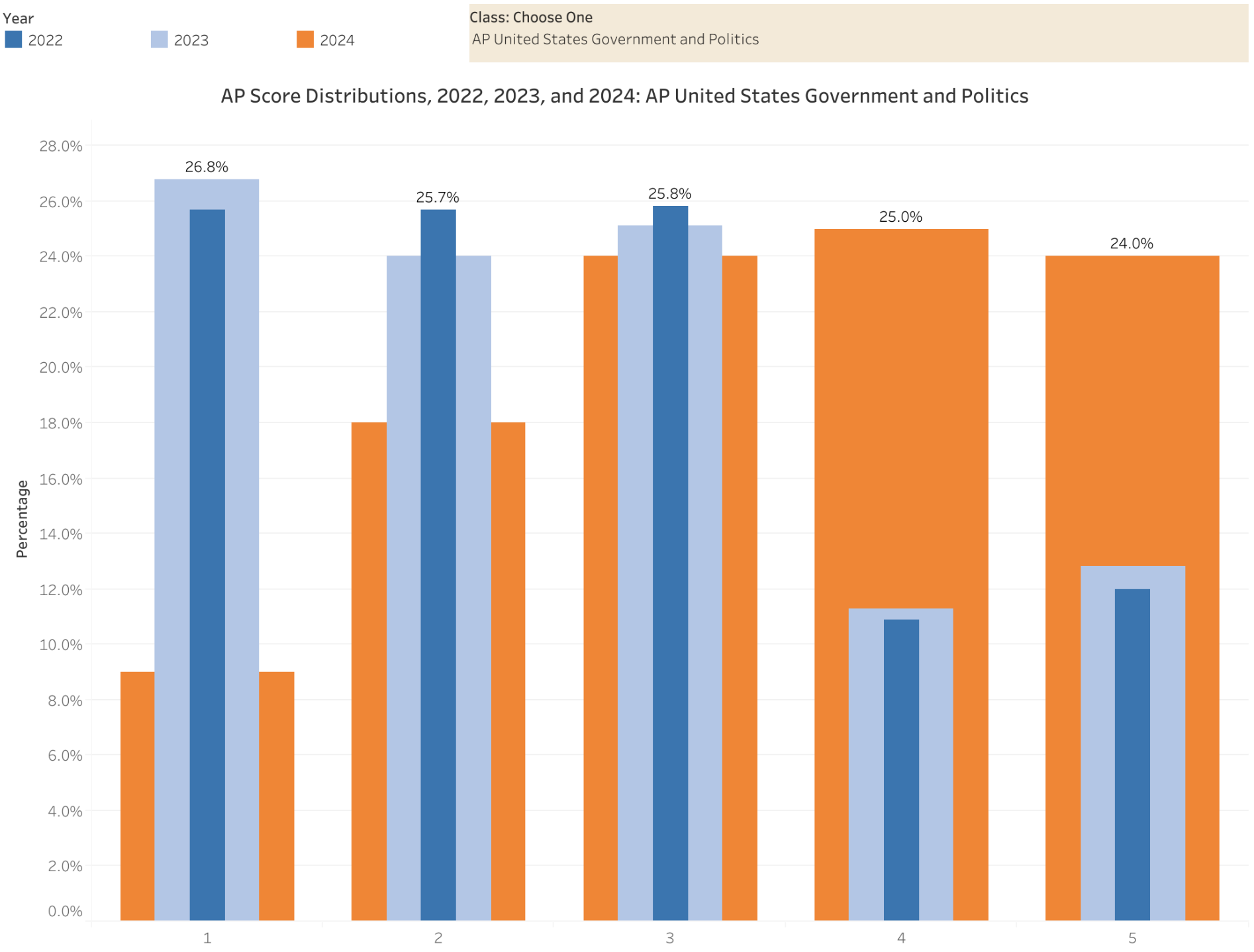

These are not minor adjustments. In AP U.S. History alone, approximately 100,000 more students have earned a score of 3 or above this year than they did last year. The interactive visualizations over at Higher Ed Data Stories are particularly compelling. Consider this breakdown of AP U.S. Government and Politics, which shows that the score distributions were not merely adjusted, they were completely inverted. Whereas the vast majority of students used to score a 1, 2, or 3 on this exam, the vast majority now scores a 3, 4, or 5.

Why is this happening?

None of this should be a surprise. The College Board has been publicly discussing recalibrating exams at conferences over the past few years. According to the College Board website, “annual studies of AP student performance in college consistently find that AP students with scores of 3 or higher outperform in subsequent college coursework the comparison groups of college students who took the colleges’ own AP-equivalent course.” By “recalibrating” AP Exams, the College Board can better align AP scores to equivalent college grades.

There is no reason to doubt the efficacy of this research, but since almost none of it is publicly available, there is no reason to accept it at face value either. The College Board has known for years—at least as early as 2021—that there are serious misalignments between AP scores and college grades. Why has the Great Recalibration been stretched out over multiple years? What about all the students whose AP Exams have not been recalibrated in time for them to earn college credits for the work they did? The lack of transparency about this recalibration project (and the uncertainty about which exams will be recalibrated in which year) has left a lot of teachers confused and frustrated.

Consider AP Environmental Science, for example. The exam has not yet undergone a recalibration, even though Trevor Packer previewed the research that showed a serious misalignment between AP Environmental Science scores and equivalent college grades. This was at the AP Annual Conference in 2023, where he also highlighted significant discrepancies between recalibrated and non-recalibrated AP Exams. It is clear that AP English Language, AP Physics, and AP Environmental Science are all overdue for a similar recalibration. AP English Language teachers have been particularly vocal about the lack of calibration for the more than 500,000 students who take that exam every year. Did 100,000 AP English Language students miss out on the opportunity to earn college credits this year because the College Board is not moving quickly enough with the research already in its possession?

Are other factors at play?

It is entirely possible that the Great Recalibration is a straightforward result of academic research in an effort to resolve the discrepancy between AP scores and equivalent college grades. The College Board claims it is following the science, and that may very well be the case, but it is possible that other factors are shaping the rollout of the Great Recalibration. Over the past few decades, the AP program has ballooned by more than 700 percent, and the program now generates approximately $500 million annually for the College Board:

- 1992: 580,143 exams

- 2002: 1,585,516 exams

- 2012: 3,698,407 exams

- 2022: 4,762,347 exams

At the same time, dual-enrollment programs have also ballooned, but those programs have little oversight and no high-stakes exam at the end of the year. Across the country, dual enrollment is competing head to head with AP. (Why risk getting a 2 on an AP Exam when you can be guaranteed college credit just for attending class?) While “recalibrating” AP scores higher may be based purely on “psychometrics,” it also confers an undeniable benefit to the AP program’s bottom line. Higher scores are good for business.

Another clue that the AP program is responding to its new, much larger audience is in the changes beyond the Great Recalibration. Many exams are getting easier with new, much simpler free-response rubrics in AP History subjects and simpler multiple-choice questions across AP English subjects. Behind the scenes, some AP Exam readers are reporting that they are being encouraged to award points on free-response questions more freely than ever before. It seems that nearly all of the recent changes to AP Exams are tending in the direction of simplification.

While it is clearly better for the program to grow and welcome students of all skill levels, the democratization of AP means that, unless all these new students meet the rigorous standards of AP, they will “fail” the exams or else the standards will need to be lowered to accommodate them. This issue was at the heart of a high-profile critique of the AP program in the New York Times last November. In that article, Dana Goldstein asked why some $90 million of taxpayer funds were being channeled into a program with so many “failing” scores of 1 and 2. The Great Recalibration may have nothing to do with this critique of the AP program, but it certainly helps address the issue.

The financial impact

Speaking of taxpayer funds, the Great Recalibration of AP Exams will affect the flow of millions of dollars into and out of high schools and colleges around the country. In states like Florida and Arizona, AP teachers are eligible to receive bonuses when their students achieve scores of 3 or higher on AP Exams. Some AP teachers in Texas are earning significant salary increases through the Teacher Incentive Allotment program when AP data are linked to improvements in their students’ outcomes. The Great Recalibration is going to help unlock even more of these public funds for AP teachers at a time when teacher pay remains dismally low.

Most public colleges and universities in the United States are required by law to grant college credits for sufficiently high AP scores. Students are able to earn college credits based on AP scores of 3, 4, or 5, depending on the policies of their college or university (the policies are searchable here). This means that when the College Board recalibrates scores for an AP exam, tens or hundreds of thousands of students will be automatically granted college credits for that exam.

The precise financial impact of this trend will depend on (1) how quickly the College Board finishes the Great Recalibration, (2) how credit policies evolve at colleges and universities, and (3) how many students actually use the credits. But the net result is undeniable and very good news for students (and very bad for colleges that will lose tuition for these credits).

The future of rigor in Advanced Placement

The College Board has argued for years that grade inflation is rampant in schools and that objective standards like SAT and Advanced Placement exams provide a stable measure of student success. But by aligning AP scores to college grades, is the College Board pegging its currency to another currency that is experiencing its own runaway inflation?

Whatever is happening with this increase in AP scores, it is destabilizing the year-over-year and course-by-course comparisons that undergird how many K–12 schools, districts, and even state governments use AP data. The College Board insists that “AP scores’ only valid use is for placing a student out of a corresponding college course” and that “AP scores have not been designed nor validated for evaluating student growth, student potential, or teacher quality.” Nevertheless, that’s not how many schools are using the numbers in practice. Will the College Board provide more guidance on how to properly use data during this era of the Great Recalibration?

I expect the Great Recalibration to continue over the next few years, and I expect this recalibration to always lean in the direction of higher average scores and a larger proportion of 4s and 5s. Will all of these changes undermine the AP program’s position as the gold standard of rigor in high school education? Probably not, but that will depend on whether anyone is actually paying attention and whether the College Board’s appeal to “psychometrics” will convince them.

Editor’s note: This was first published by Marco Learning.