The Education Gadfly Weekly: Which Republican might Kamala Harris pick for education secretary?

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Which Republican might Kamala Harris pick for education secretary?

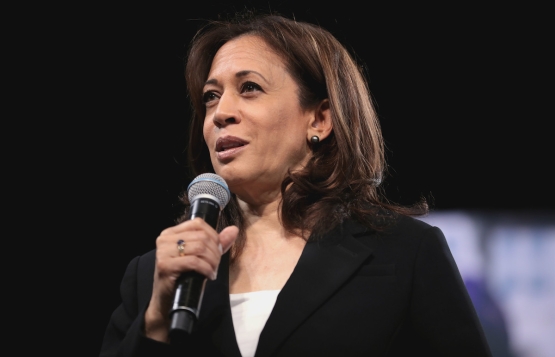

A Republican education secretary for Kamala Harris’s cabinet?

It is rare, but not unheard of, for presidents to ask members of the opposing party to serve in their cabinets. If she wins, Vice President Harris has pledged to make the symbolic gesture, historically used at key moments to project unity and bipartisanship. There’s a compelling argument to be made that the post of Education Secretary would be a worthy target for such an act. Here Chu discusses seven candidates for the role.

A Republican education secretary for Kamala Harris’s cabinet?

20 questions for school board candidates

How should teachers cover the election? They shouldn’t.

The return on investment of pre-kindergarten programming: Evidence from Connecticut

#944: More equitable advanced education programs, with Brandon Wright

Cheers and Jeers: October 31, 2024

What we're reading this week: October 31, 2024

20 questions for school board candidates

How should teachers cover the election? They shouldn’t.

The return on investment of pre-kindergarten programming: Evidence from Connecticut

#944: More equitable advanced education programs, with Brandon Wright

Cheers and Jeers: October 31, 2024

What we're reading this week: October 31, 2024

A Republican education secretary for Kamala Harris’s cabinet?

It is rare, but not unusual, for presidents to ask members of the opposing party to serve on their cabinets. Both Trump and Biden were strictly partisan with their appointments, but if Vice President Harris wins, she has pledged to bring back the symbolic gesture, historically used at key moments to project unity and bipartisanship—both of which will be in short supply no matter who emerges triumphant from this coarse election contest. The defense secretary stands out as the most common fit for such an appointment (e.g., William Cohen under President Clinton and Robert Gates under President George W. Bush and President Obama). But there’s a compelling argument to make that a President Harris would do well to shine a spotlight on education, given the federal government’s retreat on the issue in recent years.

Picking a Republican to serve as education secretary would also be uniquely historic: None of the twelve men and women who have served as the nation’s top education officer ever did so under a Commander in Chief of a different party. The New York Times recently ran a list of GOP prospects for the Harris cabinet that featured a constellation of former and current state and federal officials. Let’s work from that to see if any might fit the bill, and speculate on the implications for Uncle Sam’s role in education:

1. Sen. Mitt Romney (UT): Not seeking re-election to the Senate, Romney would be a brow-raising choice—at least among “progressives”—for education secretary, in light of his “vigorous opposition” to blanket student loan forgiveness. But he would be a breath of fresh air, given his track record on the issue dating back to his tenure as Governor of Massachusetts:

We added more school choice. My legislature tried to say no more charter schools. I vetoed that, overturned that… These kinds of principles drove our schools to be pretty successful. As a matter of fact, there are four measures on which the federal government looks at schools state by state. My state's number one among all the states in all four of those measures, fourth and eighth-graders English and math. Those principles, testing our kids, excellent curriculum, superb teachers, and school choice. Those are the answers to help our schools.

2. Sen. Todd Young (IN): It’s not reflected in his committee work, but education is an issue that’s near and dear to the senior senator from my old stomping grounds in Indiana. No fan of Trump’s, Young has called for “modernizing” America’s education system, with a focus on strengthening career and technical education. On the need for skilled workers, he might find common cause here with the “opportunity economy” that Harris keeps talking about. Young has also worked across the aisle to reduce college costs and promote upward mobility, and is a staunch supporter of school choice.

3. Former Gov. Jeb Bush (FL): For the past twenty-five years, governors have been central to education policymaking, yet few can rival Bush’s dedication to making it a top priority. During his time leading the Sunshine State, Bush implemented sweeping education reforms that set the bar for other states. His policies emphasized standards, testing, and accountability, along with school choice. Through his organization, ExcelinEd, the former governor continues to have an outsized impact on education, promoting and advocating for the reforms that he championed in Florida.

4. Former Gov. Asa Hutchinson (AR): A vocal critic of Trump, Hutchinson was spotted making the rounds at the DNC convention back in August. The former governor and GOP presidential candidate has been coy about his interest in a Harris administration but clear about his desire to add another chapter to his long and storied political career. Secretary of Education would seem to be a perfect fit if Harris tapped the folky and affable Arkansan who made computer science education a priority alongside other popular ed policies.

5. Former Gov. John Kasich (OH): Known for his centrist views and willingness to work across party lines, Kasich endorsed Joe Biden back in 2020 and briefly appeared at the Democratic convention that year. His record on education reform is extensive but without the high-profile of, say, Jeb Bush. From A–F letter grades to charter school accountability, Kasich wasn’t afraid to ruffle feathers. He may be best known for his attempt to rein in collective bargaining for teachers, an effort that was ultimately struck down by voters.

Here are a couple of others not mentioned by the Times that would also be worth praising:

6. Former Gov. Brian Sandoval (NV): A former federal district judge who has already been confirmed once by the Senate, Sandoval would be a dark horse pick. In 2015, as governor, he spearheaded what was arguably the most comprehensive education reform package in the nation that year. The dizzying array of bills flying out of the Silver State included the nation’s first nearly universal ESA law, a read-by-three law, teacher pay-for-performance legislation, additional funding to grow more charter schools, and the establishment of a special statewide district for Nevada’s lowest performing schools—which was initially led by Pedro Martinez, currently the embattled CEO of Chicago Public Schools. Unfortunately, some of these initiatives have since been repealed, but the boldness of Sandoval’s vision was remarkable for its era.

7. Former Gov. Charlie Baker (MA): Now president of the NCAA, Baker was consistently one of the nation’s most popular governors during his time in office. He firmly supported MCAS, the state’s standardized test, emphasizing its essential role in creating a “level playing field” and setting a high standard for academic achievement. Baker also appointed members to the state board of education that shared a focus on accountability and improving educational outcomes. Harris’s team should also note that the former governor has expressed interest in returning to politics.

—

Like the election itself, the selection of any of these Republicans for education secretary would be sui generis. Harris would surely face significant pushback from within the Democratic Party and the teachers unions on any of these candidates. Still, if she chose to buck her coalition’s most progressive voices—as remote a possibility as that may be—it would be less about ed reform and more about sending a signal about the importance of character, temperament, and civility as embodied by each of these estimable public servants. Of course, he or she would have to endorse enough of Harris’s education policies to make the cut, something that remains to be seen.

To be sure, nobody knows what those policies will be, but odds are Harris’s will be a continuation of Biden’s. As such, there’s little reason to get excited, regardless of whom she picks. But even if little gets done in the way of policy over the next four (or eight) years, a Republican secretary of education serving in a Democratic administration could augur well for the eventual revival of bipartisan education reform. In and of itself, that would be a minor victory.

20 questions for school board candidates

Election Day is almost here, and the presidential contest is not the only one that matters. Those of us lucky enough to have on-cycle school board elections also get to choose our representatives on perhaps the most important policymaking boards in local government. Here are twenty questions you might ask your school board candidates to answer.

1. Do you agree that our schools were closed to in-person learning for too long during the pandemic? If something like that happens again, how should the district balance the needs of students against the health concerns of adults?

2. Given the massive learning loss still plaguing our students, would you support continuing the district’s high-dosage-tutoring programs? How would you pay for them? How would you make sure they get the best results possible?

3. Chronic absenteeism continues to be a major challenge, with significantly higher numbers of students missing at least a month of school every year than before the pandemic. The absent students tend to be disproportionately kindergarteners and high school seniors. Would you support any tough-love measures to get students back to school and to hold them and their parents accountable?

4. How confident are you that the district is following the science of reading when providing literacy instruction in the early years? Can you name the foundational literacy program the district uses?

5. Data indicate that young students continue to come into our elementary schools farther behind academically than their peers were before the pandemic. Given that, would you support retaining students by no later than the third grade if they have not yet learned to read? How about adding an extra year of elementary school for these students?

6. Do you believe it is important for young students to learn their math facts, such as the multiplication tables?

7. The state requires that teachers be granted due process rights, also known as tenure, after a few years in the classroom. What do you think junior teachers should have to do to earn that designation, if anything?

8. Evidence suggests that it’s possible to recruit the best teachers to the neediest schools, but only if we pay them a sizable salary stipend, such as an extra $10,000 or $15,000 a year. Would you support such a policy? How about for principals in high-poverty schools? How would you pay for it?

9. Local officials have little control over the state pension system, which is demanding an increasing amount of district budgets, but it does have discretion over granting healthcare to retired teachers and other staff. Would you support eliminating retiree healthcare benefits, especially given the existence of the Obamacare exchanges?

10. The districts’ gifted and talented programs disproportionately serve White, Asian, and upper middle-class students. What would you do to diversify those initiatives, if anything?

11. Do you support accelerated math programs for students who are ready for them? Starting in late elementary school? Middle school? High school? Do you support honors classes in all of the academic subjects in middle school? High school? What do you think about placing all students in honors classes and no one in “on-level” ones?

12. What can the district do to increase the number of children of color and children from low-income families who participate in its Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate programs? And not just taking the classes but actually passing the exams?

13. What more should the district do to promote engaged citizenship among its students and its graduates? Is the district doing enough to teach students’ core content knowledge in history, geography, civics, science, and the arts?

14. Would you support allowing students to opt out of traditional college prep courses after their sophomore year of high school so they can focus on career and technical training, including internships and apprenticeships?

15. Are you concerned about grade inflation in the district? Do you support the so-called “no zeros” policy, whereby the lowest grade a student can receive is a 50 percent, even for assignments not turned in? What percentage of high school students do you think should be getting straight A’s? How does that compare to the situation today?

16. Do you think the district has a problem with cheating? What are the root causes? What might you do about it?

17. Do you support suspensions and expulsions for student misbehavior? If not, how would you address student violence toward teachers or their peers? Chronic disrespect toward teachers? Distributing AI-generated deep-fake nude pictures of their peers?

18. Would you support a “phones away for the day” policy? Locking up students’ phones in lock boxes or magnetized bags?

19. Studies suggest that participating in extracurricular activities, including athletics, provides all sorts of benefits for students. But these opportunities are not equitably distributed. How would you change that?

20. The district’s high school graduation rate is at an all-time high. Are you confident that all students have earned their diplomas? Do you think the district is serving its lowest-performing, least-engaged students—the ones who might have dropped out in previous eras?

Yes, these are tough questions, but being a school board member is an important job! See how your candidates do on this test—and try not to grade on a curve.

Editor’s note. This was first published by Forbes.

How should teachers cover the election? They shouldn’t.

I student-taught during the Republican primary of 2016. One afternoon, I watched my mentor teacher, an avowed socialist, berate a student during class for daring to express support for Donald Trump. After the election, many of my colleagues breathed nihilistic tirades to their charges about the hopelessness of our country. One stood sentinel in the hall every passing period wearing a red shirt with a raised fist of solidarity. All this in a purple school district.

So forgive me if I am skeptical that our teaching force is capable of covering the election without bias and with equal respect to all sides of the arguments. Given that the 1619 Project and Howard Zinn Education Project are popular online resources to which history teachers turn, the promise that schools will cover “just the facts” seems unlikely.

Almost a decade into my education career, I cannot fathom a reason that any teacher should cover the election in their classes.

Considering this argument first in a microcosm—the individual tutor and student—will bring clarity to the interests and ethics involved. Tutors receive payment to teach specific topics, ranging from academic content such as math and English to extracurriculars such as dance or piano. It would be an obvious breach of contract for tutors to stray from their hired purpose to instead cover unapproved content. Math tutors would waste their patrons’ money were they to spend their hours discussing the finer points of Tolkien’s mythology.

In the case of classroom teachers, they too are hired to teach specific content, only their patrons are society itself and their charges are a collection of students. They fill a clear, prescribed role: to teach math, American history, or whatever other course to the students in their class. A teacher of ninth grade English has no more business discussing politics than a chef at a high-end Italian restaurant has preparing lutefisk for a diner who ordered pappardelle.

There are, of course, times teachers can and should stray into controversial topics. I’m a literature teacher by trade. “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass”—these books all touch on sensitive issues. When I taught them, I never shied away from the controversies. But parents knew the content we’d cover. I often argued for positions with which I myself disagreed to challenge my students’ thinking. And the students encountered such topics in the context of history and literature, not contemporary issues. There are clear policies that school boards can enact to make sure such topics are handled prudently in the classroom.

As American Enterprise Institute Senior Fellow Robert Pondiscio never tires of pointing out, it is school boards, not teachers or administrators, who determine the content a school is to teach. As such, teachers are “hired speech.” Within school walls, they are speaking in a professional capacity and cannot spout off on price controls or whatever cause most recently grabbed the attention of their corner of Twitter.

There is a distinct, circumscribed condition where a teacher can and should cover contemporary issues: if a school board has decided that certain classes should include discussions of current events. If teachers are going to do this, though, it’s imperative that they heed John Stuart Mill’s wisdom: It is not enough that a student “should hear the opinions of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them. He must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form.”

If discussing abortion, for example, teachers should not present pro-life arguments only as strawmen to smack down. Instead, they must present their students with pro-life arguments made by pro-life advocates. A teacher should hand students conservative arguments from National Review, for example, not caricatures of them from the New York Times.

But even so, I believe such a class would be ill-advised. Contrary to popular belief, mountains of cognitive science have determined that there is no abstract skill called “critical thinking.” Discussing contemporary issues will not teach students to “think critically” in some generalized capacity. Rather, our ability to think well about a topic comes from our knowledge on that topic. Even a very intelligent professor of chemistry would provide little to a discussion of bridge mechanics or the minutiae of health care policy because he or she would likely know little about those topics.

Instead, it’s the content of courses themselves that furnish students with the knowledge that they need to thoughtfully consider contemporary issues. A student will be better prepared to discuss an impeachment if she has had read the Constitution and discussed the meaning of “high crimes and misdemeanors” in a civics class or learned of previous impeachments in history. A student will better question the motives of a politician if he has witnessed Macbeth’s violent ambition or Iago’s corrupting whispers.

As with room on a dinner plate, there’s only so much time in a school day. Filling space on the plate with junk food will leave less space for meat and potatoes.

If teachers waste time fretting over dated contemporary controversies that will likely be obscure by the day’s end, that leaves less time for a robust curriculum of history, literature, science, the arts, and other subjects that create thoughtful, wise citizens.

Editor’s note: This was first published by The Hill.

The return on investment of pre-kindergarten programming: Evidence from Connecticut

The academic impacts of pre-kindergarten programming for children are a matter of unsettled science, with some research finding a positive impact, some a negative, and much showing the fade out of all impacts by third grade or soon thereafter. A new working paper by researchers from Brown and Yale adds to this literature by examining a universal preschool program in New Haven, Connecticut. But it also looks at a less-studied question: What about the economic impacts of this pre-K program? Specifically, how much workforce support does readily-accessible childcare provide for parents?

The New Haven program was established in the mid-1990s. Its current iteration, dating to 2003, includes separate programming for three-year-olds (PK3) and four-year-olds (PK4). It is free of charge, operates mostly in New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) elementary buildings, and is available to all Connecticut residents via open enrollment. The structure includes 6.5 hours of educational curricula, as well as wraparound care starting at 7:30 a.m. and ending at 5:30 p.m. five days per week during the school year. Both PK3 and PK4 are oversubscribed each year, so seats are assigned by lottery.

The researchers started with all applications submitted between 2003 through 2022, including full data from students’ applications, the administrative rules and student priorities used to process the applications, and school placement outcomes. They observed 18,795 applications from 16,037 individuals. Just under 42 percent of applicants were Black, and 28.5 percent were Hispanic. Forty-eight percent applied to PK4, and 52 percent to PK3. The median household income of applicants was $59,708. And just over 26 percent of applicants ultimately enrolled their children in a pre-K program each year on average.

The report’s findings on academic outcomes focus on standardized test scores for students in grades three through eight, chronic absenteeism, and grade retention. To do that, all pre-K applicants were linked with NHPS records to track their academic outcomes over time. Those who went on to attend public schools anywhere in Connecticut were linked to enrollment and outcome records by the Connecticut State Department of Education. These data cover the years 2006 through 2022. A majority of pre-K applicants were tracked through middle school, many into high school and beyond.

All academic outcome impacts were null or slightly negative, with enrolled and non-enrolled pre-K applicants showing no statistically significant difference in outcomes. This was true across the board. The researchers surmise that these findings are likely due to a combination of rapid effect fadeout and parents of non-enrolled children finding other pre-K programming of similar quality.

The impacts on parental income, however, are another story. Workforce data came from the Connecticut Department of Labor, linked to parental records submitted during the pre-K application process. These were further linked to Connecticut Unemployment Insurance records and ultimately cover the years 1999 through 2022. All earnings figures were reported in terms of 2015 dollars. Administrative data were supplemented by parental survey responses from 840 pre-K applicants. It’s a small number, considering the time span of the analysis, but is positive in that they have responses from applicants in every year, even if the earliest years are more sparsely covered.

The researchers find that enrollment in the pre-K program increased childcare coverage by eleven hours per week, on average. As a result, parents of pre-K enrollees worked an average of twelve more hours per week, and their earnings increased by 21.7 percent in the year following application, as compared to parents who applied but did not enroll their children. Both administrative and survey data showed high baseline rates of labor force participation among applicants and little evidence that children’s enrollment raised these rates further. Put simply: Most parents applying for the pre-K spots were already working and looking to pre-K for support to continue, rather than trying to use pre-K to get into the labor force.

As a labor market policy, New Haven’s pre-K program is a boon. It’s pricey, yes—$15,500 per child per year (in 2015 dollars)—but each dollar of net government expenditure on this program yielded $5.51 in after-tax benefits for families, almost entirely from parents’ earnings gains, which persist for at least six years after the end of pre-K. The researchers note that this is a large return on investment compared to other labor market policies they examined. As an education policy, the picture is far less rosy. For each dollar of net government spending, education benefits were only $0.46 to $1.32. Even children’s health interventions analyzed by other researchers (such as expanding affordable health insurance for children) have been shown to generate better education returns than that.

In the end, these and other findings suggest that the academic dimension of pre-K programs may be best ignored as a value proposition (or simply accepted as having null value long-term) in favor of their workforce dimension. That doesn’t mean a lowering of quality or shuttering of programs, but simply an admission, hard as it may be, that accessible pre-K is a work support for grown-ups rather than a kindergarten training ground for kiddos. It certainly seems that working families in New Haven view them as such, and the families who were able to access pre-K placement took full advantage of the opportunity. Such a change in mindset could allow new versions of pre-K—perhaps more connected to business than to schools—and new funding sources than the public school/government-funded model that currently predominates.

SOURCE: John Eric Humphries et al., “Parents’ Earnings and the Returns to Universal Pre-Kindergarten,” NBER Working Papers (October 2024).

#944: More equitable advanced education programs, with Brandon Wright

On this week’s Education Gadfly Show podcast, Brandon Wright, Fordham’s Editorial Director and author of the latest Think Again brief, “Are Education Programs for High Achievers Inherently Inequitable?” joins Mike and David to explain why the answer to that question is “no” and why such programs are important. Then, on the Research Minute, Amber shares a study examining how individual teachers’ effectiveness shifted when instruction went from in-person to on-line during the 2020-21 school year.

Recommended content:

- Brandon L. Wright, Think Again: Are Education Programs for High Achievers Inherently Inequitable? Thomas B. Fordham Institute (October 2024).

- Building a Wider, More Diverse Pipeline of Advanced Learners: Final Report of the National Working Group on Advanced Education, Thomas B. Fordham Institute (June 2023).

- Brandon L. Wright, “Hope and progress for gifted education,” Advance (July 5, 2022).

- Jonathan Plucker, “Do programs for advanced learners work?” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (June 24, 2020).

- M. Cade Lawson and Tim R. Sass, Teacher Effectiveness in Remote Instruction, Annenberg Institute at Brown University (2024).

Feedback Welcome: Have ideas for improving our podcast? Send them to Stephanie Distler at [email protected].

Cheers and Jeers: October 31, 2024

Cheers

- Billionaire Jeff Yass will cover this semester’s private school tuition fees for students impacted by the South Carolina Supreme Court’s rejection of the state’s voucher program. —South Carolina Daily Gazette

- Solutions for chronic absenteeism should consider communities’ specific attendance barriers, balance effectiveness with cost and ease of implementation, and be evaluated thoroughly. —Thomas S. Dee, Phi Delta Kappan

- Teacher contracts should increase educators’ compensation more strategically, as well as offer them more flexibility and overhaul “last in, first out” policies. —Karen Hawley Miles and David Rosenberg, Education Week

Jeers

- The Chicago Teachers Union convinced charter school educators to join, then used its funds and political influence to undermine the public school choice movement, ultimately leading to charter closures. —Jed Wallace, CharterFolk

- Unfortunately, education policy has shifted from an “eat-your-vegetables” approach that emphasized accountability and rigorous reform to a “sugar-frosted” approach that prioritizes issues that have more immediately visible benefits for various constituents. —Rick Hess, Education Next

- Today, just one in four American high-school seniors agree that their country is exceptional, compared to 67 percent in the early 1980s. —Jean M. Twenge, The Atlantic

What we're reading this week: October 31, 2024

- To combat pandemic-induced learning loss, the federal government must take sweeping and decisive action. —Kevin Huffman, Washington Post

- Dual enrollment has surged in recent years—but equity issues persist, and it remains unclear whether such programs have encouraged any students to go to college who wouldn’t otherwise have, or helped students get through college any faster. —Jill Barshay, Hechinger Report

- From the botched FAFSA rollout to the lack of accountability regarding federal education funds, Miguel Cardona has proven himself to be the worst Secretary of Education in U.S. history by consistently prioritizing politics over student learning. —Rick Hess, National Review

Gadfly Archive

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Proof that it’s possible to approach civics and U.S. history in a balanced way

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Reflecting on Fordham’s silver jubilee

The Education Gadfly Weekly: And the wisest wonk of 2021 is…

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Charter schools at 30: Looking back, looking ahead

The Education Gadfly Weekly: The common ground on race and education that’s hiding in plain sight

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Was Eli Broad right to try to improve urban districts?

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Robert Pondiscio: Some things I’ve learned

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Biden can’t seem to decide whether all young Americans need a postsecondary education

The Education Gadfly Weekly: I believe “antiracism” is misguided. Can I still teach Black children?

The Education Gadfly Weekly: Testing, SpaceX, and the quest for consensus

The Education Gadfly Weekly: An ode to elementary schools