Grade inflation is the increase in average grades awarded to students over time, absent higher academic achievement. When students get higher grades without having learned more, their grades are being inflated. The changing meaning of grades distorts the central measure of student academic performance, as various stakeholders, from parents to college admissions officers, lose valuable information that can be used to allocate resources, identify students’ strengths and weaknesses, or hold students accountable for their schoolwork.

Worries about whether course grades are communicating distorted information are nothing new. Educational psychologist Guy Montrose Whipple wrote in 1913 that the “marking system” was “an absolutely uncalibrated instrument.” In our day, study after study shows that grades are soaring. Data from the ACT show that, in 2021, the composite score was the worst of any year reported going back a decade, but that same year, ACT test-takers logged the highest average grade point average (GPA) ever recorded. Since the beginning of the pandemic, even students at the 25th percentile of ACT performance (i.e., students performing far below average) have boasted GPAs above 3.0. That means these low-performing students received more A grades than Cs, Ds, and Fs combined. A pre-pandemic Fordham report that used data from North Carolina showed that more than one-third of students receiving B grades in Algebra I failed to achieve proficiency on the end-of-course exam, and post-pandemic studies from North Carolina and Washington State have shown further upticks in grade inflation in the wake of the pandemic.

Since grades have no intrinsic meaning, it can be tempting to believe that grade inflation doesn’t really matter. For example, a 2013 article in Educational Researcher argued that the “sky was not falling” when it came to grade inflation because cumulative GPA continued to be a good statistical predictor of college success. Princeton economist Zachary Bleemer has advanced the controversial argument that grade inflation is often good because students feel better about receiving good grades and that makes them more likely to persist with their education. Yet grade inflation apologists ignore the longer-term consequences of demeaning the value of grades. In the moment, a higher grade feels good, even if unearned, but as everyone’s expectations around grades are updated, ever higher grades are needed to achieve the same good feelings. Ultimately, the fact that there is no grade higher than an A means that rising GPAs lead to “grade compression,” where the overwhelming majority of GPAs fall within a narrower and narrower range. That’s mostly likely why a 2024 report found that test scores are now better predictors of academic success than grades, at least for the elite colleges included in the study.

But college admissions officers aren’t the only stakeholders in the grading system. Especially in earlier grades, parents are even more important. They can offer their children resources, such as tutoring, or help hold them accountable for their academics. To judge how their children are doing in school, parents tend to focus on grades given by teachers rather than other measures. Learning Heroes, for example, has surveyed parents and found that grades on report cards are the most important factor for parents when determining whether their children are succeeding at school. As grades have risen, the connection between parental views of their children’s achievement and actual academic achievement has come unhinged. For example, several post-Pandemic surveys by Learning Heroes have shown that, even in this era of devastating learning loss, about four in five parents say their child is taking home mostly A’s and B’s. As a recent report issued jointly from TNTP and Learning Heroes put it, “grades are sending signals that students are doing well at a time when there is serious reason for concern.”

It is common sense that students will study less and learn less when they have less motivation and pressure from their parents, and academic studies bear out this intuition. A 2020 Fordham Institute report used data from North Carolina to show that students assigned to Algebra I teachers who awarded relatively high grades learned less in the course. In fact, students with more lenient Algebra I teachers performed worse on assessments for subsequent math courses, such as Geometry. (An earlier study of elementary classrooms by economists David Figlio and Maurice Lucas showed a similar pattern.) A 2010 study of college students by economist Phillip Babcock shows how student effort is a crucial link between grading standards and student outcomes: When students perceive a course as being graded more strictly, they report spending more time studying for the course. In other words, students themselves respond to grading pressures, modifying their studying behavior.

In practice, grade inflation can actually exacerbate educational inequalities. After all, if students in less affluent schools receive higher grades that do not reflect their actual performance, as research indicates is happening, they may not receive the support and interventions they need to improve. A 2023 working paper used North Carolina data to show that, when a more lenient grading scale was introduced, short-term achievement was mostly unaffected but absenteeism ticked up among initially lower-performing students, indicating decreased engagement.

Keeping grade inflation in check

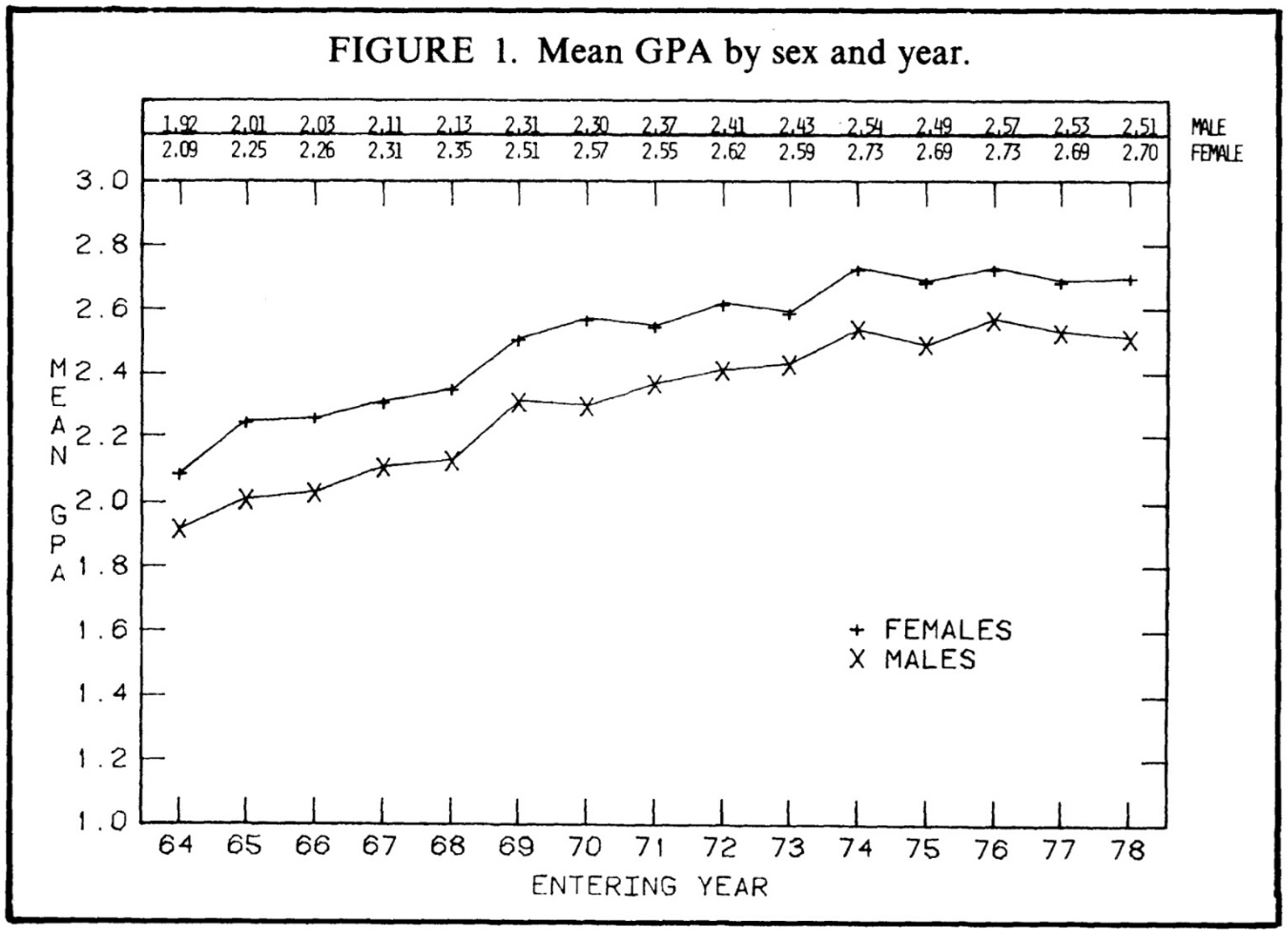

We aren’t going back to an age when the average high school GPA was 2.0 (see Figure 1), just as we aren’t going back to an economy where a vending machine Coke costs a dime. As long as we preserve the current A-to-F grading scale, probably the best we can hope for is to reinstitute the norms that were in place in recent memory, such as immediately prior to the pandemic, and hold the line thereafter.

Figure 1. Mean GPA of students taking the SAT in the 1960s and 1970s, by sex and year.

Source: Bejar, Isaac I., and Edwin O. Blew. “Grade inflation and the validity of the Scholastic Aptitude Test.” American Educational Research Journal 18, no. 2 (1981): 143–156.

To keep grade inflation within bounds, policymakers and educators should rely on three principles:

1. Develop external checks on grades.

Grade inflation is often invisible, as it is only possible to observe when grades diverge from other measures of learning. Analysts can use a range of metrics—and can even conduct in-depth academic audits—but end-of-course exams are especially valuable as external checks. When students take external exams over the same content as a course, the results provide a more objective measure of their mastery of the material, enabling analyses that can help detect grade inflation that would otherwise go unnoticed.

2. Promote transparency in grading standards.

Once grading standards are identified, the information has to be put to use. Placing grades within their context, especially by comparing them with other measures of learning, generates new data that should be provided to parents, circulated among teachers, and in some cases, included on student transcripts.

3. Avoid inflationary grading reforms.

Reforming grading has been a hot topic in recent years. Employing rubrics for grading, implementing anonymous grading, and eliminating fluffy extra credit points are all promising reforms, and importantly, they neither raise nor lower students’ grades. (Eliminating some extra credit probably raises academic standards.) These particular grading reforms stand in contrast to more controversial ones, such as eliminating penalties for late work, arbitrarily assigning grades of 50 in place of zeros, and removing all deadlines. The latter practices all weaken student accountability and further fuel grade inflation.

—

Grade inflation may seem like an abstract challenge, one that is far-removed from the question of how to best operate effective schools. In fact, grading policies influence the signals grades communicate and thus the environment in which teachers teach and students study, shaping their behavior and relationships. By utilizing external assessments, increasing transparency, and supporting reforms that preserve the rigor of grading standards, we can stabilize the value of letter grades and ensure that their meaning is clear to all stakeholders.