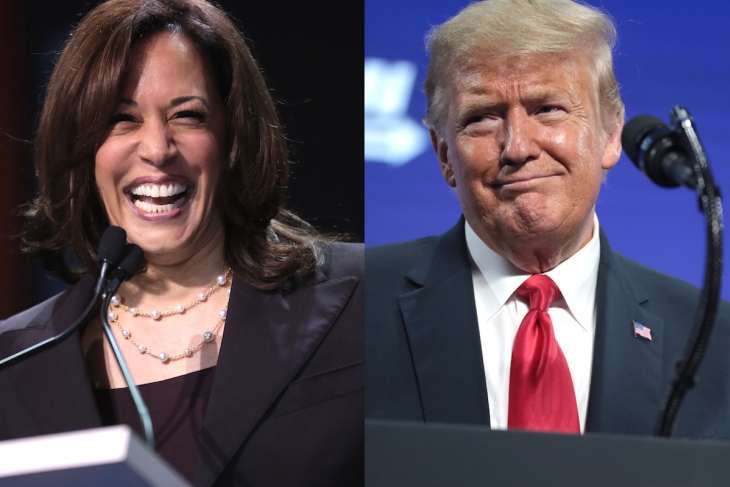

When it comes to the current storm of concern over student cellphones in schools, the conventional wisdom is that it’s educators on one side versus parents and kids on the other, as a recent EdWeek story highlights. But that’s arguably an oversimplification because it ignores a key group that might be more than happy to keep phones in classrooms: bad teachers.

First, let’s give the conventional wisdom its due. It’s true that many teenagers are addicted to their devices and won’t hand them over willingly and plenty of parents enjoy the ability to reach their sons and daughters at any time of the day. There’s also understandable anxiety about connecting in the unlikely but (sadly) plausible circumstance of a school shooting.

But research is starting to back up common sense: Phones are highly disruptive to learning in class and to healthy student socializing in the hallway and lunchroom. Thus the push by some superintendents and principals (not to mention governors and lawmakers) to embrace “away for the day” policies, a.k.a., “bell- to-bell” bans. Just as schools should be tobacco- and drug-free zones, so too should they be phone-free zones.

Teachers generally welcome these efforts. Almost three in four high school teachers “say students being distracted by cellphones is a major problem,” according to a Pew/RAND survey released in April. An EdChoice poll of more than 1,000 teachers, released in May, found only 17 percent think kids should have their phones in classrooms. A brand-new survey from the National Education Association reports an even more lopsided finding, with 90 percent wanting phone use prohibited during instructional time.

But that raises a question: Who are the 10 percent who are fine with phones in classrooms? Perhaps a few of them are technophiles who incorporate student devices into their instruction. But I have reason to suspect that others are simply bad teachers.

That hunch comes from a recent conversation with a school administrator who told me that his best teachers already make kids hand over their phones, placing them in cubbies that hang on the classroom wall. But his weakest teachers are afraid to go back to phone-free classrooms. That’s because teenagers who stare at their phones all class, zombie-like, don’t cause trouble. They are compliant. They may not be learning, but they’re also not disturbing the peace. These teachers worry what will happen when their students have nothing to distract themselves with.

Yes, this sounds cynical, but it reminds me of a famous education book from the 1980s, Ted Sizer’s Horace’s Compromise. The Horace in the title was a teacher, and the compromise he struck with his high school students was simple: If they didn’t cause any trouble, he wouldn’t make them do much work. Today, I imagine Horace would be happy for his students to bring their cellphones to class.

What Sizer knew—and what many of us seem to have forgotten—is that teaching and learning require effort and exertion. Yet when that classroom door closes, it’s easy for both teachers and students to fake it. Pop in a movie, have students read from the textbook or fiddle with worksheets, or ask them to sit quietly and “do their homework.” Add phones (or even Chromebooks) to the mix and the kids can entertain themselves forever. It’s the school equivalent of those mechanical mouse jigglers that some remote employees use to make it look like they are working when they are not.

Ban the phones and the worst teachers are going to have to up their game—which is another great reason to do it.