Last week, the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) released updated school report cards that offer a plethora of data from the 2023–24 school year. My colleague Aaron Churchill did a deep dive into achievement and growth indicators. But state report cards also present data on “non-academic indicators,” including chronic absenteeism, which is defined as missing at least 10 percent of instructional time for any reason.

Chronic absenteeism has been a hot topic over the last few years. That’s largely because, during the pandemic, the number of students who were chronically absent nationwide shot through the roof—and then stayed there. But it’s also because we have a lot of data indicating that regular school attendance is good for kids and chronic absenteeism is not. Students who have never been chronically absent are six times more likely to read on grade level by the end of third grade and nine times more likely to graduate from high school on time. On the flip side, being chronically absent can negatively impact both academic and social-emotional development.

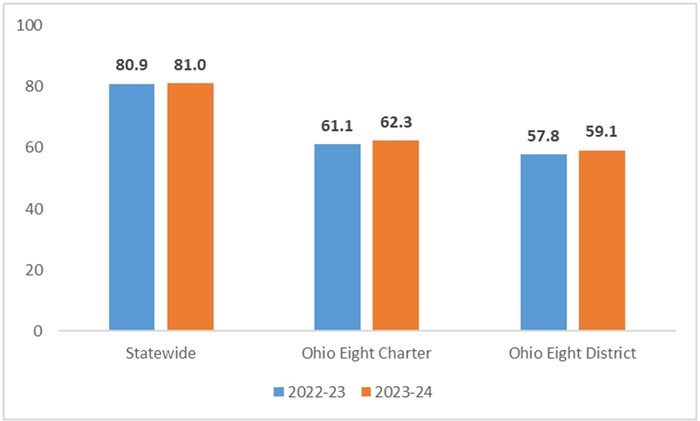

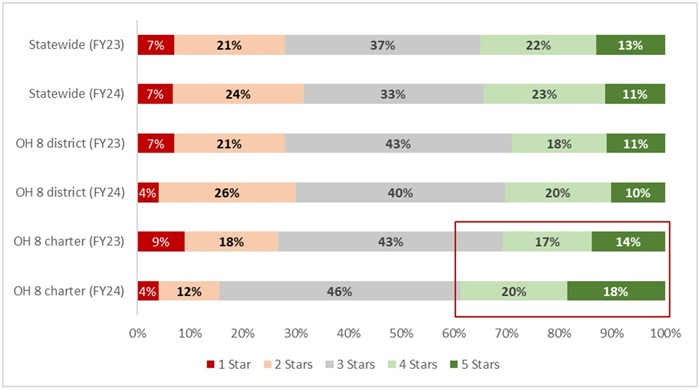

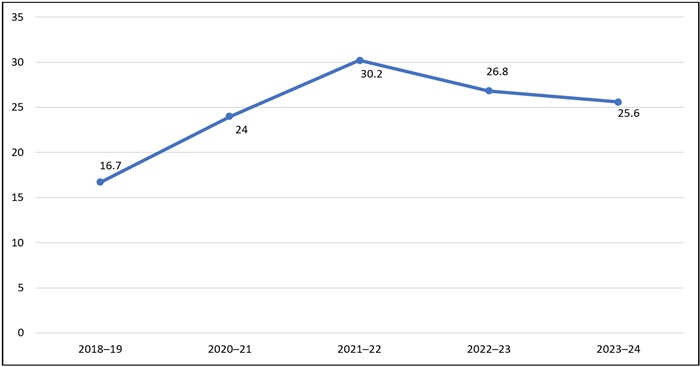

Given these data, many hoped that Ohio’s latest round of school report cards would show a big drop in chronic absenteeism rates. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Figure 1 below displays Ohio’s statewide chronic absenteeism rate for the most recent years. In 2018–19, the rate was just under 17 percent. By 2021–22, that number had jumped to 30 percent, meaning nearly a third of Ohio students were missing significant class time. Though still too high, the statewide rate ticked down to 26 percent the following year and seemed to promise the start of a downward trend. But the 2023–24 school year produced a rather disappointing rate of 25 percent. The trend is still technically downward. But a decline of 1 percentage point isn’t nearly enough.

Figure 1. Statewide chronic absenteeism rate, 2018–2024

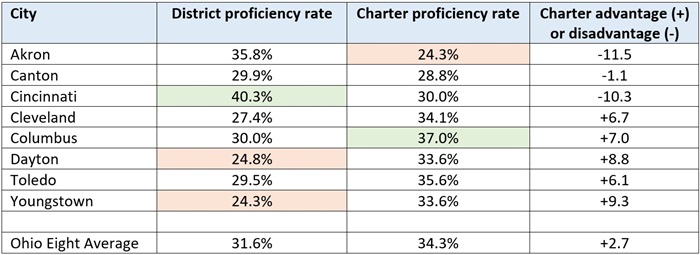

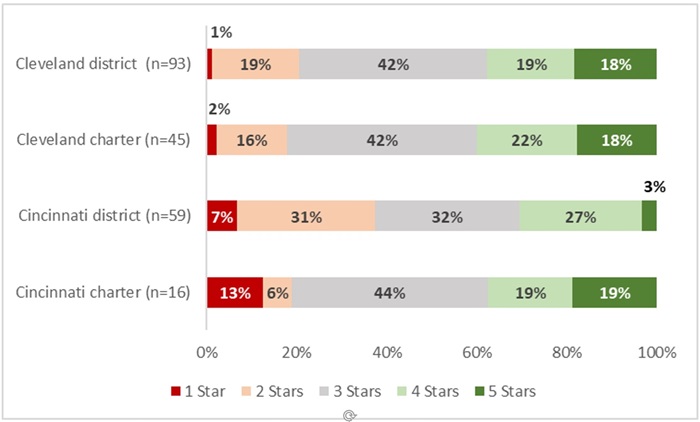

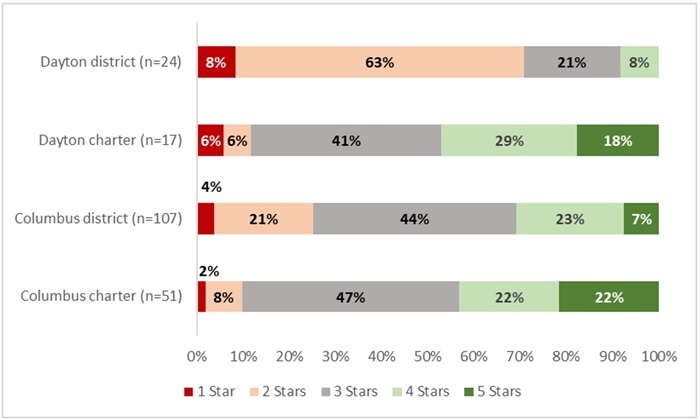

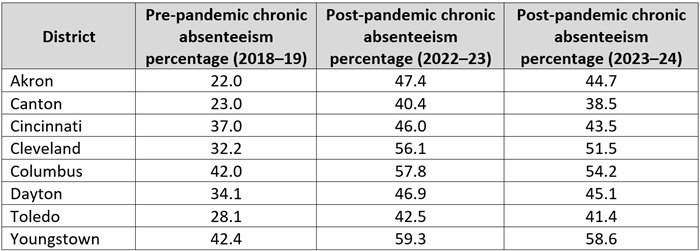

There hasn’t been much improvement in high-poverty districts, either. The table below provides the pre- and post-pandemic chronic absenteeism rates in the Ohio Eight, the state’s major urban districts. On the one hand, their progress in cutting chronic absenteeism outpaces the state. But no district registered a drop of more than 5 percentage points. And in at least three districts—Cleveland, Columbus, and Youngstown—the chronic absenteeism rate remains above 50 percent. That’s a full-blown attendance crisis, as a majority of students enrolled in these districts are missing significant amounts of school. Given that most students in the Ohio Eight are already behind academically, all that lost instructional time is particularly worrisome.

Table 1. Pre- and post-pandemic chronic absenteeism percentages in the Ohio Eight districts

The good news is that state leaders have already signaled that addressing chronic absenteeism is a top priority. Ohio recently joined more than a dozen other states in pledging to cut chronic absenteeism by half over a five-year period. Most of this work will occur at the local level, where it will take a team effort from teachers, principals, community members, and families to move the needle. But there are some things that state policymakers can do to support them.

First, leaders must use their platform to emphasize the importance of attendance. One way to do so would be to launch a statewide public relations campaign that communicates the importance of consistent attendance. A recent report from the Ad Council Research Institute found that successful messaging must have a positive tone and “communicate the opportunities associated with in-person learning” rather than the consequences of absenteeism. That kind of messaging is exactly what schools in northeast and central Ohio (and a few other places, as well) have already experienced via the Stay In The Game! Attendance Network. Ohio leaders could build on those efforts with a statewide campaign that reaches every community. The Ad Council report also found that teachers are the messengers whom parents trust the most when it comes to attendance. A positive statewide messaging campaign (or something like this effort in Massachusetts) that reinforces what families are hearing from their students’ teachers could help immensely.

Second, state lawmakers should commit to maintaining accurate attendance data tracking. Over the last year, there have been attempts to water down data accuracy and transparency by making it easier for students to miss school for “legitimate” absences. While there are plenty of valid reasons for students to miss school, Ohio can’t afford to alter how it tracks those absences. Doing so would only make it look like chronic absenteeism rates have improved when they actually haven’t.

Third, policymakers should use the upcoming budget to direct DEW to take data transparency a step further. Rhode Island is an excellent model, as leaders there have created several publicly available, interactive tools. The state’s real-time attendance dashboards update daily, and show daily, weekly, and monthly attendance trends in individual schools, along with data on early dismissals and tardies (both of which can have a sneakily big impact on chronic absenteeism). The daily chronic absenteeism update allows users to track the percentage of students, by district and grade span, who are already chronically absent, as well as how many of those students reached that threshold during the previous year. The historical absences dashboard does exactly what its name suggests and provides historical data going back to 2017. And the chronic absenteeism and achievement dashboard outlines the importance of attendance by tracking its impact on state assessments. Ohio should create its own version of these dashboards, so that local officials, district and school leaders, and families have detailed and timely data that emphasize the importance of regular attendance and pinpoint where intervention efforts are most needed.

Last fall, the Ohio Attendance Taskforce emphasized that effectively addressing chronic absenteeism would take a team effort. One year later, in the wake of report card data showing minimal progress, the need for urgent action remains. Much of the heavy lifting will fall on the shoulders of local schools and community leaders, as they’re the ones who are most trusted by parents and regularly interact with kids. But state leaders play an important role, too, and implementing the ideas outlined above would be a great place for them to start.