This is second in a series where I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget. The first covered the state’s science of reading initiative, and this essay looks at the way Ohio counts—and funds—low-income students.

Everyone today agrees that low-income students tend to need more resources to achieve rigorous standards and exit high school ready for college or career. Such students usually come from more challenging backgrounds and face obstacles that—without strong supports—can lead to achievement gaps. Teaches also tend to demand a salary premium to serve in high-poverty schools, which is another reason to provide extra dollars.

In line with this thinking, Ohio has long provided additional funds to needier schools. This academic year, Ohio will allocate $563 million in Disadvantaged Pupil Impact Aid (DPIA)—one of the components of the overall school funding formula. These dollars are intended to cover the costs of providing supplemental services, such as high-dosage tutoring, extended learning time, and other interventions.

Additional funds for low-income students remain essential to the state funding system, but lawmakers must improve the way dollars are steered to districts and charter schools. The underlying problem is that Ohio misidentifies thousands of higher-income students as “economically disadvantaged,” which in turn thins the dollars available to support students who are actually low-income. Fortunately, as discussed below, there is a solution—“direct certification”—that would improve the accuracy of these data and better ensure that funding goes to support students who need it the most.

Problems identifying “economically disadvantaged” students

Along with several other states, Ohio uses a students’ eligibility for federally subsidized meals to identify them as economically disadvantaged. In the past, this method worked out reasonably well. Eligibility for free-or-reduced-priced lunches was restricted to students from households earning less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level.[1] Hence, disadvantaged numbers used to more accurately reflect students who were low-income.

Congress, however, relaxed eligibility requirements in 2010 by enacting the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). This policy allows qualifying[2] mid- to high-poverty districts and individual schools to provide subsidized meals to all students—regardless of their family income. While this has reduced the administrative burden of verifying incomes and perhaps improved child nutrition, CEP has eroded the quality of economically disadvantaged data in states like Ohio.

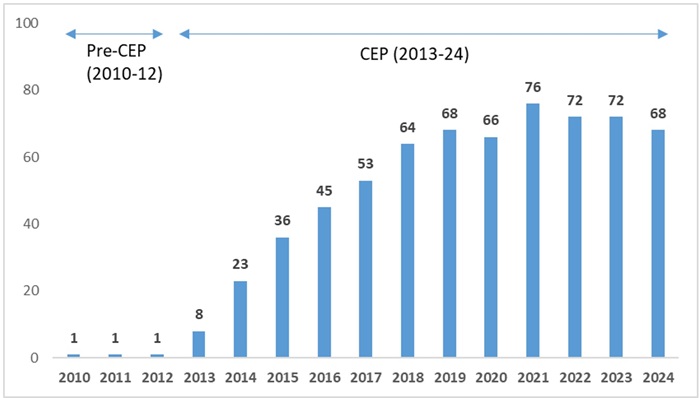

Figure 1 displays the marked increase in the number of districts reporting universal to near-universal disadvantaged rates after the introduction of CEP. Prior to 2012–13, the first year of program implementation in Ohio, just one district (Cleveland) reported all students as disadvantaged. With CEP, that number began to rise and since 2017–18, more than sixty districts—roughly one in ten—have reported rates above 95 percent.

Figure 1: Number of Ohio districts reporting 95 percent or more students as economically disadvantaged

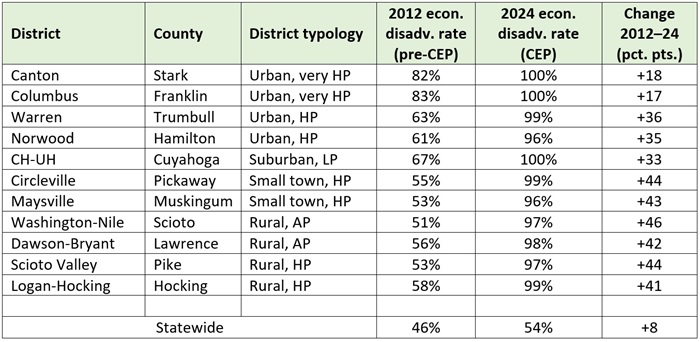

As the table below indicates, many of the districts that report universal rates today had nowhere near those numbers prior to CEP. Circleville, for example, had a disadvantaged rate of 55 percent in 2011–12. This year, the district reports nearly every single student as disadvantaged. As shown at the bottom of the table, the statewide disadvantaged rate has also climbed. Note that an actual increase in low-income students cannot explain these jumps, as Census data indicate a slightly declining childhood poverty rate for Ohio over the past decade. Instead, today’s sky-high disadvantaged rates reflect the impact of CEP.

Table 1: CEP districts reporting the largest changes in disadvantaged rates in each district typology

Inflated disadvantaged rates lead to unfair allocations of state aid

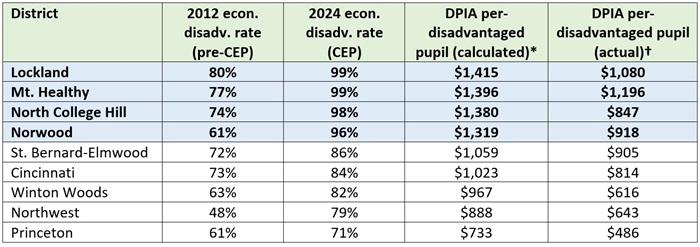

Because DPIA funding is tied to disadvantaged rates, CEP districts reap windfalls while similarly situated non-CEP districts receive substantially less. Table 2 shows stark differences in per-pupil DPIA funds for CEP districts in Hamilton County versus other districts that likely have similar numbers of disadvantaged students. As the fourth column indicates, the four CEP districts receive more than $1,300 per disadvantaged pupil under a fully phased-in formula—far more than their non-CEP peers.[3] Column five indicates that two of the CEP districts receive more than $1,000 this year under the actual “phased-in” formula. These amounts are considerably higher than what non-CEP districts receive, even though they’re also high poverty. Cincinnati, for instance, receives approximately 20–25 percent less per disadvantaged pupil than Lockland and Mount Healthy. Princeton receives roughly half of what Norwood receives in DPIA, despite historically having an almost identical disadvantaged rate.

Table 2: DPIA funding for selected districts in Hamilton County (CEP districts shaded in blue)

Toward more accurate headcounts and a fairer allocation of DPIA

To ensure accurate data on disadvantaged students and to improve the allocation of DPIA, lawmakers should make two changes.

First, they should require the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) to identify low-income students based on direct certification. Rather than counting students based on meals eligibility, this process identifies low-income students through a records match with their families’ participation in programs such as SNAP, TANF, or Medicaid.[4] Tennessee and Massachusetts have moved to using direct certification to count low-income students, and this process is already used in Ohio to determine districts’ and individual schools’ eligibility for CEP. By removing higher-income students from Ohio’s disadvantaged headcounts, direct certification would yield more reliable data on low-income students.[5]

Second, lawmakers should then use these more accurate data to drive DPIA funding to schools. While fewer students would be identified as economically disadvantaged under direct certification, it would allocate dollars more fairly to districts. Moreover, with fewer disadvantaged students identified and more confidence in the data quality, Ohio could (and should) boost the per-pupil DPIA funding so that low-income students receive even stronger supports.

Properly funding low-income students’ educations should remain a priority for state lawmakers. Yet without a reliable method for identifying them, Ohio is misdirecting millions in funds. The state’s current funding formula is often hailed by supporters as the “Fair School Funding Plan.” To live up to that impressive billing, lawmakers must shift to a more accurate count of low-income students.

[2] Until recently, to qualify for CEP, districts and schools had to identify at least 40 percent of students as low-income through direct certification—a process in which students are certified as low-income based on their families’ participation in SNAP, TANF, or other means-tested programs. Starting in October 2023, the federal government lowered the threshold to qualify for CEP to 25 percent of students direct certified. This could further increase the number of CEP districts and schools in Ohio.

[3] Some of the non-CEP districts are likely to have individual schools that participate in CEP (e.g., Cincinnati).

[4] Other flags that indicate disadvantagement such as a homelessness or foster status could also be included.

[5] More accurate identification of disadvantaged students would also strengthen research that seeks to study the impacts of policies and programs on low-income students, as well as accountability systems that aim to hold schools accountable for the academic outcomes of disadvantaged pupils.