Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2024 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to answer this question: “How can policymakers and practitioners radically reduce chronic absenteeism—at least below pre-pandemic levels and preferably much further?” Learn more.

A strong signal that schools are not serving the needs of kids and families is the “chronic absenteeism crisis” in our country today. We need to stop putting the blame at the foot of kids and families, and instead, look to the school system that fails to educate and engage our children.

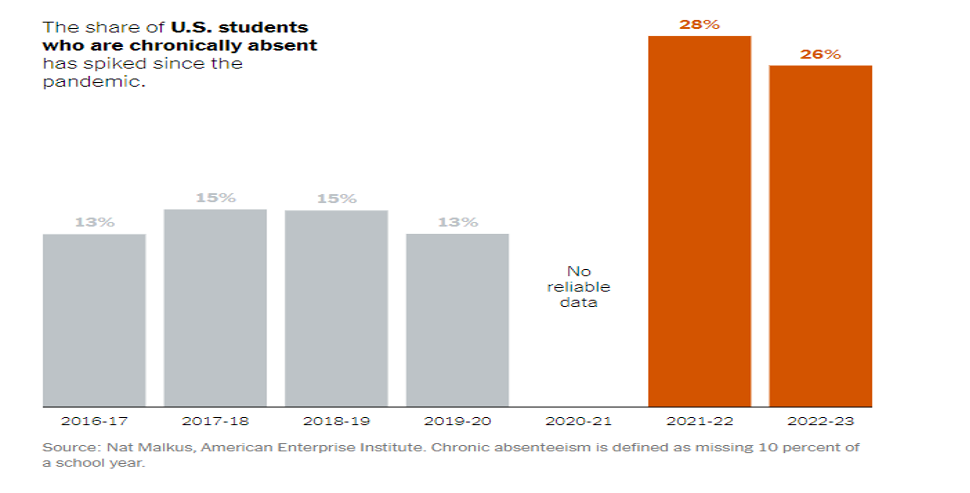

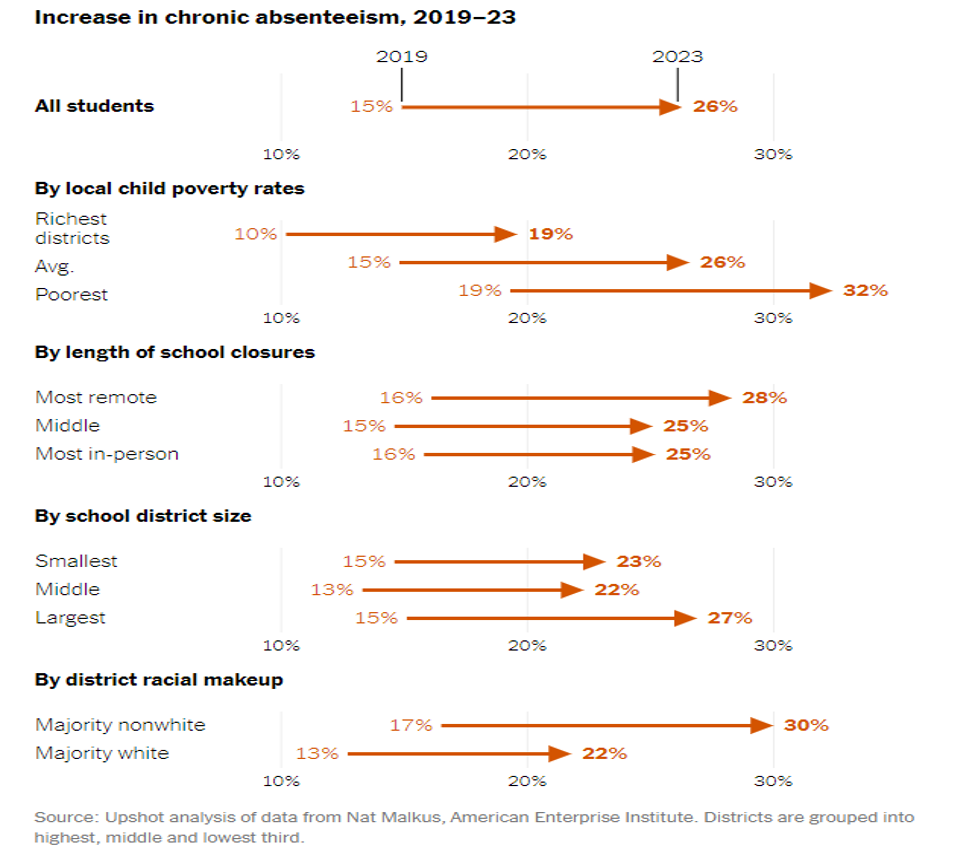

Many are deeply concerned about chronic absenteeism because it cuts across racial and socioeconomic divides. Absenteeism is up across the board from 15 percent in the 2018–19 school year to 26 percent in the 2022–23 school year, according to a report from American Enterprise Institute earlier this year. It was even covered in The New York Times. They report, “Students can’t learn if they aren’t in school. And a rotating cast of absent classmates can negatively affect the achievement of even students who do show up because teachers must slow down and adjust their approach to keep everyone on track.” This argument is more indicative of a deeper issue of our school system that policymakers can solve with creative partnerships and by empowering families and entrepreneurs alike.

First, they need the buy-in of a key partner in solving the problem: parents. According to Brookings, parents are not aware (or overly concerned about) their kids’ absences from school. Parents are aware, however, that it takes extra work for a kid to catch up after absences; of those surveyed by Brookings, 22 percent noticed their child struggled after missing six or more days of school in the first half of the 2023–2024 school year. Meanwhile, other parents think the ability to make up coursework online or from home is a viable option, while still preferring in-person interactions for their child. So what is best here? Empower parents. Brookings concludes equipping parents with longitudinal data about their kids to understand that their kid is missing X more days than they used to, or Y more days compared to peers could be useful information for parents to change behavior. There’s some preliminary evidence this works from a Philadelphia experiment: When parents are seen as a partner and key stakeholder in the educational journey, then opportunities abound.

Chronic absenteeism also highlights how the classroom is designed for the “average” student and that “achievement” is the end-all be-all of the school system. As parents and academics alike already know, there is no such thing as an average student. When classrooms design for “average,” they are designed for no one. This is one way our school system continually fails to engage kids on both ends of a learning spectrum: struggling or excelling. In an Education Week conversation between Rick Hess and Jal Mehta, it was acknowledged that the absenteeism conversation does overly focus on the kids as the problem, rather than the schools, and asks a key question: Could we make school a place where kids want to go? Mehta shares an example from Salem, Massachusetts, where students were involved in a human-centered design process to inform school leaders as they redesigned their middle school with a flexible curriculum, increased community engagement, and more hands-on, project-based learning. In this small example, absenteeism decreased by more than 50 percent.

Additionally, the overemphasis on achievement and grades brings with it excessive and unnecessary pressure for kids. Brookings found the reason with the strongest relationship for missing school to reported absences was, “a child’s anxiety about peers, tests, or in general.” It is bad enough that kids are not engaged in school, but what may be worse is that their current engagement is driven by a fear of failure, leaving them too anxious to attend classes and contributing to the chronic absenteeism problem.

With all of this in mind, chronic absenteeism is the symptom of a larger problem with our education system: Attendance is serving an outdated purpose, and student progress is being measured in outdated units of time. Meanwhile, there is a vast marketplace of education alternatives (some that actually only require two hours of academic instruction) that has exploded post-pandemic. Education entrepreneurs are serving educational needs in local communities across the country. Pair this with historic enrollment declines, and it’s clear parents and kids alike can be a part of the solutions because they are already voting with their feet.

So what does all of this mean for policymakers?

1. Policymakers can ensure parents and families are empowered with choices for their kid’s education and ensure those parents and families are aware of the variety of options available to them. This could take shape in the form of a Learn Everywhere program, like in New Hampshire, or in the form of an Education Savings Accounts, like in Arizona and Utah (among others).

2. Possibly more importantly, policymakers can unleash entrepreneurship by promoting policies that ensure entrepreneurs are free to solve the problem inside and outside of the public system. There are plenty of entrepreneurs out there who are getting creative with education alternatives, but regulatory barriers abound and are stifling solutions.

Chronic absenteeism is an indication kids want something different for their education, and their parents are listening. Policymakers are in a prime position to encourage participation from a variety of stakeholders from parents, to kids, to community leaders, to entrepreneurs who can shape and redesign schools with the potential to increase student engagement, improve parent satisfaction, and radically reduce absenteeism.