- “Are schools quarantining too many students?” —Education Week

- New books by Michael Sandel and Adrian Wooldridge discuss whether the Western world’s move toward meritocracy has been a net negative or positive, but Wooldridge’s use of history makes for a stronger case. —Jay P. Greene

- “CDC: An unvaccinated teacher took off their mask to read aloud. Half the class got Covid.” —Education Week

- This year’s Education Next poll of over three thousand parents found that support for reforms such as school choice and free college is falling as parents yearn for a return to normalcy. —Education Next

- A decade of data on high-school-to-college transition interventions for struggling students finds mixed results. —Brookings

The past eighteen months have been some of the most tumultuous in the history of our nation. The twin pandemics of Covid-19 and social injustice have highlighted how today’s students face very different expectations than students encountered in previous generations. In 2021, new graduates need to engage in diverse communities, appreciate the workings of a global economy, solve complex and changing problems, and navigate new technologies. Given the widespread use of social media, we need young Americans to be wise consumers of information, engaged citizens, and advocates for their beliefs. And all of this comes in the face of substantial economic disparities, job and food insecurity, and the increasing fragility of our democracy.

It is no surprise then that many are making a case for refreshing the teaching and learning of civics and U.S. history in K–12 education. Fordham’s new report, The State of State Standards for Civics and U.S. History in 2021, which compares state standards that typically govern the development of civics curricula and textbooks, is a tool to help guide that transformation. The recommendations included in the report make it clear that democracy is not merely to be studied. We know from brain science that hands-on learning and lived experiences help ideas stick. Competencies such as critical thinking, historical analysis, and problem solving—all prevalent in what we at the Hewlett Foundation sometime call “deeper learning”—must be a part of how we build and sustain civic learning for students from a young age.

Suppose today’s students had greater knowledge of and confidence in our democratic institutions. This is what I hope Fordham’s report triggers, assuming we take to heart not only its findings but, more to the point, its recommendations for action. Chief among them is to spend much more time, much earlier in the academic lives of students, on both civics and history. Another, with which I particularly agree, is to put considerably more emphasis on argumentation and problem analysis in making connections to current events. Helping students use what they know to make sense of the world around them and supporting them in thinking through how they make the world a better place is the right aspiration, and we should get to it.

We must also be sure not to underestimate what very young children are capable of learning. Hewlett’s own grantmaking reveals that competencies like critical thinking are determinative in a world where a command of the facts is necessary but not sufficient in preparing young people for work or life. I would even propose going a step further by exploring ways in which the voice of students might be amplified and leveraged in support of their own learning. They can learn about democracy by engaging in it. As such, time spent in school clubs, youth organizations, and other extracurricular activities can, we think, become effective incubators of civic behavior and learning. Our standards for civic learning should reflect this.

If we have learned anything from previous standards-setting or revision efforts, it is that they need to be demonstrably more inclusive. Taking stock of civics standards is a start, but I worry a lot about how unequally civic learning opportunities are distributed across communities and schools. It is something I wish received more attention in the report. Bringing high-quality civics and history standards to life, as has been the case with other standards, will require investment—in new curricula, in professional learning opportunities for educators, and in new forms of assessment.

Nor am I sure where I come out on the matter of specificity versus ambiguity. I take the point that standards should be clear, concise, and, I might add, relatively few in number. But I am less sure if our goal should be to center a given set body of information or to develop fully in today’s students the capacity to grapple with many sets of facts and interpretations of those facts. I think there is a dividend associated with thinking about the challenge as one of shifting from codifying a given body of knowledge to more of a competency-based approach to history and civic learning.

Of course, the very act of choosing the knowledge we want students to know is contentious. We experienced this during heated debates over national history standards in the 1990s, and it is reasonable to expect that we might again have a similar experience, especially given the polarization in our country today. The good news is that the focus of Fordham’s report is on what state (versus national) education officials can do. We should expect there to be legitimate variation in standards in accordance with demographics, geography, and political realities.

In any event, and as this report suggests, it is hard to see how we emerge from our current state of affairs without much improved civic education. Let’s embrace this central theme and get on with this task. Making the case that civic education matters, which the report does, is a good place to start. The report also reminds us that history, as a discipline, is an important component of civic education because it is a natural platform for getting young people to think critically and to place the problems we will need them to solve in context. This, for me, is the essence of deeper learning. Focusing us on the standards that often shape the decisions we make about what to teach and how to teach it may not be the whole ball of wax, but it is a part of the solution. It is in this spirit that I applaud Fordham’s work.

At Partnership Schools, we believe that one thing that separates effective turnaround efforts from failed experiments is the ability of the leader to articulate a clear, coherent, and actionable vision for change. While talk of “leading with vision” may conjure up eye-roll-inducing images of vapid or vague mission statements or empty platitudes, it’s actually a critical (and sometimes under-valued) piece of the school improvement puzzle. That’s because without a clear vision—one that can be succinctly explained to faculty, staff, and parents and one that is informed by data, grounded in programs that have a proven track record of success, and supported by effective professional development and coaching—turnaround plans are easily derailed, undermined, or simply too vague to drive real, lasting results.

Partnership Schools, of which I’m superintendent, is a network of nine urban Catholic schools serving more than 2,300 students in New York and Cleveland. As we prepared to welcome students back for the new school year, we gathered our school leaders to reflect on what leading with vision means, especially in the face of the challenges our communities continue to face in this pandemic.

For us, leading with vision is more than an aspirational pep talk. It has significant implications for how we function as a network—and for the work of each principal, dean, and operations leader at our schools. As a school management organization, we have a strong model, shared curriculum, common pacing guides and expectations, and shared systems for functions like tuition. But we also have an ethos that tends to eschew mere compliance. We are not a network driven by a common sense of “command and control,” but rather a sense of “this is our why.”

In practice, that means that steering a Partnership School involves more than charismatic leadership or compliance-focused implementation. Rather, it asks three things of all leaders:

- Knowing your “why.”

- Mastering your “what.”

- Leading with conviction.

Know your “why”

Lately, I’ve been drawn to a video clip that illustrates how a mission-driven orientation—which is embedded within Catholic schools—has the power to drive change in ways that go well beyond what makes any sense given the resources we have and given the struggles we face.

In the video, when comedian Michael Jr. asks a music teacher to sing “Amazing Grace,” the version he shares when he is deeply grounded in his “why” isn’t just beautiful. It also moves the audience around him in a way that his first, technically proficient version does not. Functioning from our why can make all the difference.

As crucial as our emotional motivations are, when it comes to vision-driven leadership, knowing your why doesn’t stop there. It is also important to know why we do the things we do in the course of our work. Why do we ask teachers to follow a pacing guide in core content areas? Why do we have a dress code, or use a particular system for grading? Our picture of vision-driven leadership demands that we get clear for ourselves—so that we can communicate effectively to our teams—why we make the choices we do. Knowing the why is important for building buy-in and support for an improvement plan, and it’s essential for communicating with parents, particularly in these times of uncertainty.

But the “Amazing Grace” clip doesn’t just inspire us to know our why and work from it. It suggests that we need something more than a clear why to have the impact we seek.

Master your “what”

When watching that short clip, it’s easy to glide past just how technically proficient this “Amazing Grace” singer is to focus on the difference between the two renditions. Yet while the second song is the one that knocks us off balance, both versions show that this is a leader who knows his stuff.

When I think of the most outstanding leaders I’ve ever seen or worked with, what Boston College professor Dr. Ellen Winner calls a “rage to master” is at the heart of how they function. They may also bring charisma and inspiration. But first, they bring expertise and humility.

When I think about the expertise and humility that effective leaders need to drive improvement, I’m often reminded of a quote from Pablo Casals. When asked at the age of ninety-three why he still practiced three hours a day, the master cellist responded, “Because I think I’m making progress.”

When it comes to school leadership in general and vision-driven leadership, in particular, I think not of obsession or perfectionism, but rather a relentless focus on figuring things out.

In sports, we’ve grown not just to appreciate this type of relentlessness, but to celebrate it. As just one example that was profiled in the 2018 ESPN documentary, In Search of Greatness, a clip of American skateboard legend Tony Hawk trying to land the first-ever 900 in the 1999 X Games provides a master class in illustrating this “rage to master.” Hawk hopes to land the 900 during regulation play, and he fails repeatedly. But he just simply can’t give up. He falls, returns to the top, and makes tiny adjustments, learning with each failure. Finally, several minutes after the competition has ended, he lands the 900 and the crowd goes wild.

It isn’t just persistence that Hawk demonstrates. It’s a deeply curious, detailed, technical pursuit of his craft. While school leaders don’t need to obsess to that level on every detail of school management, effective school turnaround does require a similar relentlessness of focus—a commitment not just to launching a headline-grabbing plan, but to watching, learning, and making the kind of unsung tweaks and refinements that will ultimately drive real, lasting change.

Lead with conviction

The final piece of vision-driven leadership is the part that can be the scariest. Basically, it’s the moment when you have to say: “I know my what. I know my why. Everyone is looking at me to make a decision and to see it through.”

Of course, seeing a decision through doesn’t mean acting like a bull in a china shop. It doesn’t mean being stubborn and not listening to pushback. But it does mean that you must be willing to take a risk and make a judgement call—while facing the reality that you might be wrong and you might fail.

One of the things I appreciate most about working in a network is that you have peers in similar roles facing similar challenges who also need to make decisions. This makes leadership less lonely, but it doesn’t dilute the importance of you making decisions as a leader and seeing them through.

—

We know that our schools can tap into and unleash the greatness within our students because urban Catholic schools have been powerful engines of social mobility and flourishing for generations. As Partnership Assistant Superintendent Christian Dallavis described it to our leaders: Our work is similar to that of sculptor Michelangelo, who said that he “saw the angel in the marble and carved until he set it free.”

In a time when our children need a great educational environment more than ever, our ability to meet their needs means being even more grounded in a clear vision. That requires knowing why we do the hard work of running schools in a pandemic, pursuing the craft of educating with a relentless drive for excellence no matter what challenges we face, and having the conviction to act on behalf of the emerging angels who will walk in our doors in the next few weeks.

“Hi. Welcome to the future. San Dimas, California. 2688.” Rufus, played by George Carlin, thus opened the American film classic Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure by explaining that, in the distant future, everything is great. The water, air, and even the dirt is clean. Bowling averages are up, Rufus explained, and miniature golf scores are way down. I have a report from your state’s much more immediate future that also ultimately constitutes good news. Over a decade ago, the Great Recession kicked off a chain of events that caused Arizona school districts, even the suburban ones, to get very active in open enrollment, accepting students from other communities.

Get ready. A similar dynamic could soon unfold in your state.

Arizona is the demographic canary in America’s coal mine. As both a retirement destination and a border state, Arizona reached your state’s age (older) and demographic future (more Hispanic) faster than you did. But you’ll soon be here. Daily between now and 2030, an average of 10,000 baby boomers will reach the age of sixty-five nationwide, making your state a bit more like Arizona. America’s Hispanic population continues to grow around the country, which is also moving the country in Arizona’s demographic direction.

Arizona experienced rapid population growth for decades after World War II. In the 1990s, the state passed a robust charter school law and required school districts to have open enrollment policies. Suddenly, in 2008, the nation plunged into a housing-lead recession, and K–12 enrollment growth stalled.

Charter school operators still able to access capital in the financial chaos saw an opportunity to serve more students in the property crash. Real estate will likely never be as inexpensive again. But the number of charter school students essentially doubled, and now Arizona has the highest percentage of charter school students, at almost 22 percent.

In the process, Arizona districts became choice operators themselves. Scottsdale Unified, for example, currently has about a fifth of their students coming into the district through open enrollment. The key to spurring open enrollment wasn’t laws. It was incentives. The bureaucracies needed the money, and as some suburban districts got more active in open enrollment, it created competitive pressure on other districts to do the same.

A majority of Phoenix area students do not attend their zip-code-assigned school. District open enrollment students outnumber charter students almost two to one, despite Arizona having the largest charter school enrollment. Perhaps not coincidentally, during all of this, data collected by Stanford University sociologist Sean F. Reardon showed that Arizona students ranked first in academic gains between 2008 and 2018. They learned more per year of schooling during this period than any other state and had strong growth across multiple subgroups.

So what does this have to do with your state? Events seem to be conspiring to crack open suburban districts for open enrollment broadly. First, there was a national baby bust going on before Covid-19. Worst still, a survey by the Guttmacher Institute found that one-third of American women polled in late April and early May wanted to delay childbearing or have fewer children because of the pandemic. This will pinch enrollment.

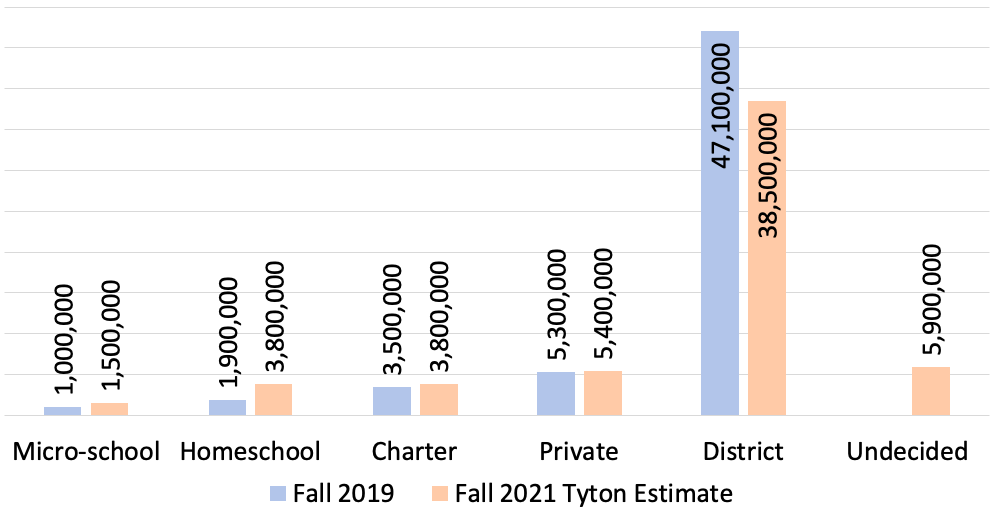

Second, the pandemic has seen a gigantic increase in homeschool enrollment and the creation of an entirely new micro-school sector. Tyton Partners created a panel study of American families to estimate national enrollment trends. Figure 1 below presents its estimates for fall 2021.

Figure 1. U.S. enrollment projections for fall 2019 and fall 2021, by school type.

Source: Tyton Partners.

Noteworthy about these estimates: The 1.5 million micro-school students represent the smallest sector, but it took charter schools seventeen years to reach a similar number of students. Almost 6 million students lived in families who were undecided on where their children would attend in the fall 2021. If the undecided in the Tyton estimates choose school sectors similar to those who decided early, it would still result in district enrollment rolling back to 1999 levels. The Census Bureau also reported that 11 percent of students are being homeschooled, while the Tyton estimate showed a smaller increase. One suspects that there is conceptual confusion or overlap between the micro-school and homeschool sectors that we may clarify over time. Whether one or both of these estimates are off, it seems like a good bet that they both represent growing sectors.

The third event that will broaden open enrollment is that a number of states have made very strong improvements to existing choice laws and created new ones.

The upshot of this is that many suburban districts are going to find themselves short of students, which means that many may lower the drawbridge to allow in open enrollment transfers to avoid closure. When this happened in Arizona, the choice knob got turned to “11.” Almost all Arizona districts participate in open enrollment now, even the fancy suburban ones.

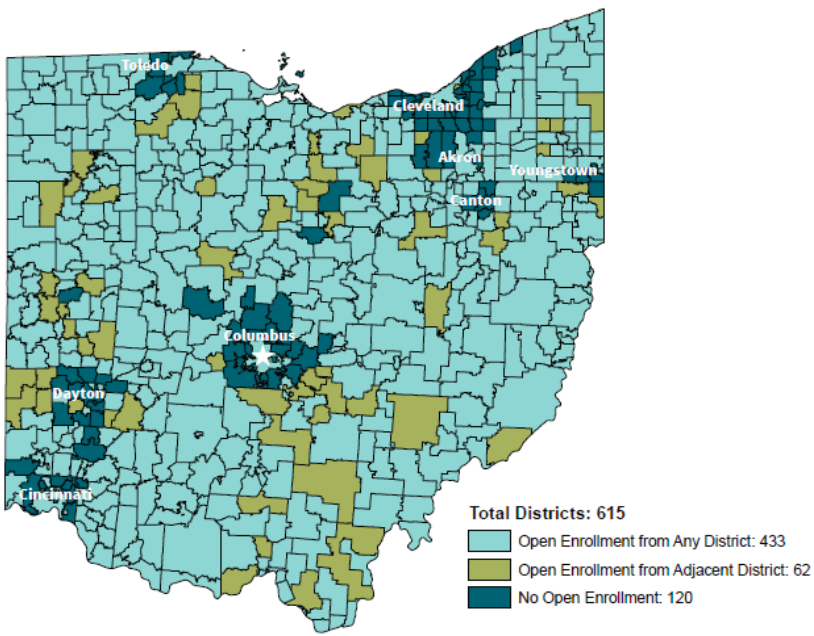

Meanwhile the world as you knew it at the cusp on the pandemic looked more like Ohio than Arizona. In a January report, the Fordham Institute colored every school district in Ohio according to whether they took open enrollment students. In figure 2, notice the almost complete absence of suburban districts taking open enrollment students.

Figure 2. Ohio school districts by open-enrollment status, 2017–18 school year.

Much to their credit, Ohio lawmakers have since addressed this situation, removing geographic restrictions on charter schools and creating and strengthening private choice programs. And there’s a push among choice advocates in the state, including from Fordham, to pass legislation creating statewide open enrollment.

A system of school based more on opportunity and less on suburban opportunity hoarding empowers families to decide which schools remain open and which close. It’s also cost-effective, allowing schools to get more learning for each dollar spent. Did I mention that Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure was filmed in Phoenix? We’re obviously proud of that too, but you are on your own for improving bowling and miniature golf scores or making the dirt clean.

Black Lives Matter protests, raging wildfires, a monumental election, and the global pandemic. As a seventeen-year-old growing up in Portland, Oregon, these past eighteen months have been the craziest I have ever experienced. Never would I have thought that I would essentially miss the entirety of my junior year of high school, forced into taking classes in a solely online environment. Yet quarantine has given me time to reflect on everything I’ve learned throughout my years of school, as well as how I’ve been taught.

After reading Fordham’s report on Civics and U.S. History, I realize how lucky I am to have received a solid education in these subjects in high school—and how helpful it would have been to start learning that content at an earlier age.

I don’t recall learning much history in elementary or middle school, except perhaps that, a long time ago, a large group of men sat in a small, sweaty room and signed a document that led to the establishment of our country. It wasn’t until high school that I received the sort of rich and balanced civics and U.S. history education the report envisions.

As a freshman, my school required me to take a U.S. History: Ethnic Studies class, where I studied topics like the Great Recession and Japanese internment. Although it was interesting, and I am glad to have taken the course, I think it would have been more beneficial and productive if I had known more U.S. history when the course started. As the Fordham Report states, “Before kids can critique something, they need to know something.” I wholeheartedly agree.

My first real introduction to civics and U.S. history came in my sophomore year, when I participated in the We the People High School Constitutional Competition, a program created by the Classroom Law Project to further the civics education of high schoolers around the country. Each year, a maximum of thirty-six students per school are selected and divided into six units, each of which specializes in a different period of Constitutional history, from the philosophical and historical foundations of the American political system to the challenges American constitutional democracy faces in the twenty-first century.

As a member of Unit Five, I focused on the Bill of Rights and the associated U.S. Supreme Court cases. Over the course of the year, I also learned about our country’s founding, important events that have shaped the U.S., and how our government functions.

For me, the program was eye-opening. I had never before realized the importance of learning about our democracy and our Constitution—or just how much there was to learn. Because of the program, I feel the empowerment of being a well-informed and engaged citizen. I also realize how important it is for every student to get a good civics education.

And yet, the harsh reality is that most schools don’t have a program like the one I participated in.

That’s why I agree with the Fordham Report’s vision for civics and U.S. history education. If these subjects were prioritized from the moment students set foot in kindergarten, I believe more of us would grow into politically involved adults. Of my acquaintances at school, only those who were a part of the Constitution Team seem to understand the importance of political participation.

The Fordham Report gives Oregon an “inadequate” overall rating, with a D- in civics and an F in U.S. history. This is consistent with my personal observations, which suggest that my experience has been much better than most of my Oregon peers’.

My hope is that every student in the country can have the sort of opportunities I have had. Our citizens must, as the Fordham Report says, “understand, value, and engage productively with the constitutional democracy in which we all live” in order to, as the Preamble to the Constitution says, form a more perfect union. That starts with stronger civics and U.S. history education.

Ohio Charter News Weekly will be on hiatus next week; returning on 9/10/21.

Kudos

The state board of education this week chose Stephanie Siddens as the Interim Superintendent of Public Instruction. She will take the reins in September when current Superintendent Paolo DeMaria retires and while a search for a permanent replacement is ongoing. Siddens has been with the Ohio Department of Education for 15 years, most recently as Senior Executive Director of the Center for Student Supports.

Help wanted

Districts and charter schools in the Miami Valley region are reporting difficulty in filling many positions as the new school year gets underway. Both Dayton City Schools and the Horizon Science Academies told the Dayton Daily News that finding enough intervention specialists to serve their students in special education was an especially difficult task this year.

New year, old myths

The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools celebrated the new school year by busting a quartet of charter myths, including three very old, standard-issue canards. The fourth, that public support for charter schools is dropping, is perhaps a bit newer but seems more like wishful thinking from charter opponents than any legitimate widely-held misconception. It, too, is busted nonetheless.

The school choice landscape

University of Notre Dame sociology professor Mark Berends published a new report in the Phi Delta Kappan journal called “The current landscape of school choice in the United States”. He lays out not only the numbers and types of charter schools and voucher programs in use today but also the numbers of students utilizing them and the findings of the best research regarding them. A compact, detailed, and important read.

Spending priorities

The Associated Press took a look at how schools and districts across Ohio were planning to spend their federal Covid-relief funding over the next three years. It is significant that the piece looked at the state’s largest online charter school—Ohio Virtual Academy—and took pains to point out that “[v]irtual school students experienced the same pandemic-related anxieties and mental health stress” as other students. OVA’s current and future spending on more counselors and psychologists, as well as increased summer offerings, and support for families needing help with home internet costs are detailed.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Parents, educators, and experts agree: Millions of American children are facing major mental health challenges related to the pandemic and associated school closures. Thankfully, we’ve already seen administrators begin to ramp up services to support students when they return to school full-time this fall, with the help of billions of dollars in new federal funding. But as traumatized students come back to class, we also need educators ready to handle increased behavioral issues, as some kids “externalize” the suffering they’ve been through and re-learn how to “do school” again. Unfortunately, the discipline policies in place in many schools nationwide may actually exacerbate the challenge, potentially setting us up for disaster.

That’s largely due to the multi-year campaign to reduce suspensions and expulsions, as well as the number of school security guards and police in the corridors. In the past year, according to Education Week, at least thirty-three school districts, serving more than 800,000 students, have eliminated their school police officers, and both Los Angeles and Chicago have reduced their budgets for school security and the number of officers in their schools.

Unlike the movement to “defund the police,” which is generally seen as a fringe position, the movement to “defund the school police” while curbing suspensions and expulsions of disruptive students is getting support from high places. The Democratic attorneys general from twenty-two states plus the District of Columbia signed a letter this spring calling on the Biden administration to reinstate Obama-era limits on discipline in the classroom, a process that administration officials have since launched.

The impulse is understandable. There continue to be big disparities by race and class in the use of exclusionary discipline, as well as in arrests of students by school police officers. Black students, in particular, are two to three times as likely to be suspended, expelled, and arrested as their White peers. Reducing these disparities, it is hoped, will interrupt the so-called “school to prison pipeline.”

Whatever you think of this analysis—and there are good reasons to doubt the conventional wisdom—the answer can’t be simply to stop disciplining kids who misbehave or act out. Indeed, just as less policing can lead to more crime, less discipline can lead to more disorder in classrooms and school corridors.

That’s doubly true, given what so many students have been through over the past year, including suffering from higher incidence of neglect or abuse, dealing with the economic struggles associated with parents’ unemployment, grieving the deaths of friends or loved ones, and the social isolation and loss of routines from not attending school in person. On top of which come the heightened anxieties associated with America’s belated reckoning with racial justice, the murder of George Floyd, and the awful spike in violent crime in most cities. Tragically, all these stressors have hit Black, Hispanic, and poor children harder, on average, than their White and middle-class peers, given the unequal impact of the pandemic and other crises of the past year.

Now imagine what may happen when we combine all that with a cutback in security personnel and new policies on school discipline that make it harder for teachers and principals to address misbehavior. At the very least, we should expect a rise in classroom disruptions, creating yet another barrier to addressing the learning loss experienced by so many children over the past year, plus student pushback to Covid-19 protocols like masking or social distancing. Much worse would be a spike in school violence, akin to what we’re seeing now on too many streets.

Sadly, the victims of disorder and violence are much more likely to be students who are themselves poor, Black, or Brown, and who live in the high-poverty neighborhoods that have been most harshly impacted by this year’s events. It’s going to be hard enough to get their families to send them back to school, given the spike in cases driven by the Delta variant. Imagine how many parents will make their kids stay home if they sense that their schools are out of control.

So what can educators do to support students as the school year begins? By all means, schools and their community partners should continue to expand mental health supports for students, especially in the toughest schools with the greatest needs. And principals need to get to work building (or rebuilding) a positive culture of high expectations, trust, and affirmation. But they also need a realistic plan for addressing misbehavior when it inevitably arises. This can be done respectfully, seeking to help young people understand and meet high expectations around behavior; punishment is not the point. Nor does it necessarily mean more out-of-school suspensions or expulsions. In-school suspensions that allow students to follow their classes via video from down the hall are something we should consider now that the technology is widely available. (The Dallas school district, for example, plans to experiment with reforms along these lines.)

But our empathy for what so many kids have been through shouldn’t lead us to embrace lax discipline standards that prevent the safe and orderly return of students this fall. Two years ago, the Fordham Institute surveyed teachers nationwide about discipline policies. The most interesting responses came from a representative sample of Black teachers. In general, they agreed that Black students were unfairly disciplined, but they also wanted more discipline in their schools, not less.

Educators and policymakers, including Biden administration officials, would be wise to listen to those teachers and come into the new school year with eyes wide open and ready to tackle these challenges. In particular, they should rethink their efforts to reduce policing and discipline in the schools. Our kids have been through enough over the past fifteen months. The last thing they need is for us to allow their classrooms, cafeterias, and corridors to become conduits for further pain and suffering.

Parents across the country are up in arms over their school systems’ equity initiatives. To be clear, this is not “equity” as I came to define it when I started teaching nearly a quarter century ago. No, in the late nineties, “equity” was commonly understood as keeping a focus on outcomes and holding all students to high expectations, especially those living in marginalized communities. Indeed, the term so defined was the coin of the realm among education advocates of all stripes. Since then, however, “equity” has been slowly bastardized and adulterated to such ill effect that it’s been rendered almost bankrupt of meaning.

This insolvency was underscored in a new episode of the 8 Black Hands podcast titled “Dumb things done in the name of equity.” The show examined recent examples of actions taken in schools with the purported goal of benefiting students. From purposely segregated classrooms to privilege walks, the four co-hosts—Ray Ankrum, Charles Cole, Sharif El-Mekki, and Chris Stewart—offered their analyses and critiques of what’s been happening amid our raging culture wars and currents of negative partisanship. By my lights, the pandemic has unwittingly provided cover to further erode what little currency “equity” has left. Three examples from this summer come to mind:

Ditching grades in California. The first is an emergency statute that was signed into law in July requiring all districts in the Golden State to allow high school students to erase any letter grade received during the last academic year and instead receive a Pass or No Pass. Shifting a letter grade to pass/fail likely increases a student’s GPA—a critical part of a college application, and more so in California, where most post-secondary institutions no longer require SAT or ACT scores. There are no limits to how many course grades or which courses can be changed in this way. Notably, some parents are not even aware of the new law. And can you guess which families those are likeliest to be?

This well-meaning but misguided policy attempts to “show grace” to high school students, especially those from low-income backgrounds, who spent most of the year online wrestling with a subpar educational experience. This diktat fails, however, to recognize the unintended consequences pointedly observed by Doug Lemov: Doing away with grading usually benefits those least in need. In this case, the students who are able to whitewash their poor marks are skewing an already imperfect process to their own advantage.

Ditching graduation standards in Oregon. Look no further than California’s neighbor to the north to find how prevalent the impulse has become to lower the bar for Black and Hispanic students. Last month, Oregon’s governor quietly signed a bill that allows students to graduate without proving that they can write or do math. A spokesperson explained that the new law provides for “equitable graduation standards, along with expanded learning opportunities and supports.” This lavish trafficking in feel good language shouldn’t fool anyone in light of the danger that Oregon’s new policy poses to students.

AEI’s Rick Hess has (as usual) penned a scathing piece that’s exactly on point. “It’s hard to think of a policy more threatening to minority kids than the insistence that it’s okay for them to graduate without being able to read.” What’s worse, proponents of the law seem to have used their ideological distaste for standardized tests as justification for their “reform,” no matter that Beaver State students have had multiple ways to demonstrate mastery of standards and need not pass any exam to graduate. One would be hard pressed today to find another state plumbing lower depths when it comes to failing to meet its basic obligations to students and families. But tomorrow may show that we haven’t yet reached the bottom.

Trying to ditch academic testing in New York. Not to be outdone, a group of teachers in the Big Apple just launched a bid to ditch academic testing, among other items, via an online petition that has already exceeded its initial goal of five thousand signatories. The group calls for “no academic screening/diagnostic assessments for so-called deficit of learning/learning loss.” Making no effort to obscure their true intent, they add, “We desire a pause in required high stakes state standardized testing until performance-based alternatives are explored.” Their message seems to be, “Never mind the billions in dollars of academic relief Uncle Sam is pouring into our schools. Just take our word for how your kids are doing ‘because equity.’”

This episode is as callous as it is grotesque. The petitioners have threatened to walk if they don’t get their way—this after two years of disrupted learning in Gotham schools. It takes a particularly virulent strain of unscrupulousness to issue ultimatums after all the trials and tribulations that parents and students have recently suffered. As in California and Oregon, “equity” is being deployed here as a smokescreen, but the academic needs of children are nowhere to be found.

—

When it comes to doing what’s best for America’s neediest students, these three incidents make it seem as if some have thrown in the towel. To be fair, Covid-19 has exerted pressure on schools and systems in unprecedented ways, but that’s all the more reason for elected leaders and officials to stand up for students. What’s more, those who attack objective measures of merit while flying the flag of “equity” would do well to consider the long-term ramifications—an admonition that Stewart voiced at the close of the podcast:

How many of our kids are actually leaving your schools capable of doing something in the world that changes all the numbers we care about: homeownership, jobs, income, business development, ability to get government contracts and loans, and qualifying for things that require qualifications?… [I]f [what schools do in the name of equity] doesn’t end up with us with more capital somewhere down the line, it’s nonsense.

Nonsense indeed.

In the early days of the pandemic, I was dismissive of “new normal” talk about Covid’s long-term impact on schooling. There was good reason for skepticism. Americans may hold in low regard public education at large, but we have long demonstrated a deep and abiding fondness for the schools that our own children attend. The idea that the pandemic had transformed us into a nation of homeschoolers, hybrid and distance learners, and micro-schooling enthusiasts struck me at the time as akin to insisting that passengers thrown from sinking ships into lifeboats had taken up rowing.

With the prospect of a third school year disrupted or rendered unreliable due to Covid, I’m a lot less confident about this take than I was sixteen months ago. Mounting evidence suggests that parents are becoming more likely not just to say they support school choice, but to actively choose an alternative to their local public school—at least the school their kids attended when the pandemic hit.

The New York Post reported this week that enrollment at a top elementary school in Brooklyn’s well-off Park Slope neighborhood has shrunk by a third since the start of the pandemic. Kindergarten enrollment has fallen by more than 50 percent. “School sources said some families have abandoned the city outright while others are opting for local parochial or private schools with consistent full-time schooling,” the Post reported.

The word “consistent” is key, and the calculus is pretty simple: Parents want good schools, but of equal or greater importance are reliable schools. No one in the wonk world likes to think of school as daycare, but working parents, even those with the luxury of working from home, need to know that the plans they’ve made for their children’s education aren’t likely to change at a moment’s notice.

There could be non-Covid factors at play in the case of this Park Slope school, but it reflects a larger theme: Brooklyn is the object of a controversial “community-based diversity plan” engineered by New York’s former schools chancellor Richard Carranza, a plan that not every parent supports. For over a year, parents have had direct and unfiltered access to what their kids are doing all day, prying open for millions the black box of teacher quality, curriculum, and classroom culture, with school Zoomed directly onto kitchen tables. For many, perhaps most, it was reassuring. For others, not so much. The past several months have seen countless examples of agitated parents complaining to school boards about diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, and protests over programs and curriculum informed by critical race theory. Even as schools prepare to return to full-time, in-person instruction, fights over mask mandates or their absence have further strained bonds to the breaking point.

For all these reasons, it’s becoming clearer that the long-standing relationship between parents and local schools they have long supported has become unstable, particularly among relatively well-off families with other options. But everywhere you look, the trend appears deep and wide. Data from thirty-three states obtained by Chalkbeat and The Associated Press show that public K–12 enrollment this fall has dropped across those states by more than 500,000 students, or 2 percent, in the past year. In Philadelphia, for example, kindergarten enrollment declined by more than a quarter between fall 2019 and fall 2020. Hawaii’s schools, which operated almost entirely remotely last fall, suffered one of the biggest declines in the country—down 14 percent between fall 2019 and fall 2020, according to the New York Times. Overall enrollment at all 178 Colorado school districts has dropped 3.3 percent across all grade levels.

Of particular note is the unaccountable behavior of the teachers unions, most notably the American Federation of Teachers, whose President Randi Weingarten has been on a public relations suicide mission for months, brazenly insisting she has been working to reopen schools, despite lobbying the CDC to manipulate school reopening guidance. She seems blithely unaware that parents’ patience is not inexhaustible, and bizarrely determined to alienate her members’ most stalwart supporters: parents like those in Park Slope who pride themselves on being good progressives and public school parents. Writing in Commentary, Christine Rosen takes note of a rising tide of parent activism, particularly among liberal and progressive parents—“because it was in their Democratic, union-dominated states that schoolchildren were most likely to languish in virtual learning.” It has become a common joke among choice advocates that Weingarten has done more for their cause than anyone since Milton Friedman.

Choice advocates have long lamented the disconnect between parents’ stated preference for school options versus their revealed preference, namely how relatively few families opt out of their zoned schools. I suspect they underestimate the big ask they’re making of parents. The act of sending our children to a local neighborhood school is a cultural habit formed over generations. As I wrote sixteen months ago, it persists because we value it, not for want of alternatives or a more efficient delivery mechanisms for education. But with a third school year opening under a cloud in many places, that “big ask” is starting to feel a lot less burdensome than it used to. The Overton Window has shifted significantly. For a growing number of families, the greater burden may now be staying put.

I’m still of the mind that “new normal” talk is overwrought, but I’m far less confident of that assertion than I was at the outset of the pandemic. The long-standing practice of sending kids to zoned neighborhood schools is still a hard habit to break. What I didn’t expect was how many public school supporters—from governors and teachers unions to local administrators and school boards—would be so determined to break it.

With reporting by Jessica Schurz.

When it comes to career and technical education, there’s one state that seems to be getting things just about right: Connecticut. It boasts a long history of strong CTE programming and, thanks to efforts beginning in the early 2000s, all the locally-administered career schools across the state were integrated into a single statewide system known as the Connecticut Technical High School System (CTHSS). Today, the system includes seventeen diploma-granting technical high schools and one technical education center, serving approximately 10,200 full-time high school students—a whopping 7 percent of the state’s high school student population—with comprehensive education and training in thirty-eight occupational areas.

How well do those schools prepare students for postsecondary success? A recent working paper from a trio of researchers from the University of Connecticut and Vanderbilt University seeks to answer this question. The quasi-experimental study is the first of its kind, examining the causal impacts of attending a comprehensive high school CTE program. The strength of this study comes from the fact that it examines every school in the system, thus examining a program that is being offered at scale, whereas previous analyses used only schools that agreed to participate in the study.

CTHSS is a unique, all-encompassing program that begins when students apply for admission as eighth graders. They can apply to up to three schools and rank order their choices. Application scoring is based on standardized eighth grade test scores in math and English, student GPA, attendance in middle school, and extracurricular activities and written statements. School administrators establish a threshold score for admission, and students above that threshold are generally first to be offered seats. Because the schools are always oversubscribed, however, remaining seats from students that decline an offer are offered to applicants with lower application scores. Some students below the threshold are admitted in the first round to increase diversity.

Because of the complexity of the admission process, researchers in this analysis use a “fuzzy” regression discontinuity model that treats application scores as cut scores. Students just above the threshold are 87 percent more likely to receive an acceptance letter, and such students are more likely to attend the school to which they applied, compared to students just below the threshold. Importantly, researchers also create separate models for male and female students to account for the well-documented gender differences in CTE specialization, with men focusing on construction and manufacturing trades and women on human services and tourism. Counterfactual schools were determined by the town or city in which the student resided in eighth grade when applying to CTHSS. This was a strong counterfactual, as most students attend the high school in the district they live in if they did not receive admission to a CTHSS school.

Part of what makes this study so strong is the size and quality of the panel data used to perform the analysis. Researchers used applications from approximately 57,000 eighth graders who applied to CTHSS between 2006 and 2013. These students are then matched to the Connecticut Department of Education’s longitudinal data system, and information on race, gender, free-and-reduced-price-lunch status, English-learner status, and special education status is collected, in addition to short- and medium-term outcomes, like standardized test scores prior to and during high school, attendance, and high school graduation. Then they use National Student Clearinghouse data to determine the number of semesters of college attended, if any, between high school graduation and the first quarter of 2018. They also match graduates to the Connecticut State Department of Labor’s employment data through the state’s P20 WIN initiative.

The first finding to note: Attendance at a CTHSS school had no effect on female student outcomes as compared to non-CTHSS peers. For male students, however, attendance at CTHSS increases high school graduation rates by 10 percentage points (relative to the sample average of 83 percent) and reduces the number of semesters ever enrolled in college by almost one half of a semester. For the full sample, CTHSS students see 44 percent higher total earnings and 32 percent higher quarterly earnings than their counterfactual sample means. CTHSS graduates’ earnings show a marginal decrease around age twenty-three, but are still a whopping 33 percent higher than the earnings of their non-CTHSS peers.

In discussing the potential mechanisms that yield these results, the researchers first point to higher motivation among students while attending CTHSS. Attendance rates at CTHSS schools are 1.7 percentage points higher than the counterfactual school, tenth grade test scores improve by 18 percent of a standard deviation, and math and English language arts scores improve by 13 and 16 percent of an SD, respectively. CTE coursework positively contributes to student outcomes, an effect boosted by the integrated experience of that coursework in the fully career-focused CTHSS schools. They also suggest that CTHSS students, and indeed students who take CTE courses in non-CTHSS schools, gain important general work skills that are in demand, readily marketable, and scalable with increasing experience. Finally, rather than seeing the earnings decline around age twenty-three as a negative, the researchers suggest it is an indication that older CTHSS graduates are pursuing formal college or advanced certification once they are more financially secure.

Overall, the effects of CTHSS attendance and graduation seem undoubtedly positive for the young men participating. But the lack of any positive effects for young women is concerning. If acquiring general and marketable work skills is the key, why isn’t it working for girls? One explanation could be that efforts to boost college enrollment and success among female students have borne fruit in recent years, which could help explain why CTE does not appear to be a positive experience for them. Even those young women graduating from CTHSS may simply be moving on to formal higher education, as if a career high school is the same as any other secondary educational track. Or perhaps it’s not that career and technical education is good for boys, but that general education is bad for them. Whichever the case, we cannot look askance at the CTHSS model, which does appear to be working very well for many young men as a springboard toward higher earnings. Making sure that more girls can gain the same marketable skills would be icing on the cake.

SOURCE: Eric Brunner, Shaun Dougherty, and Stephen L. Ross, “The Effects Of Career And Technical Education: Evidence From The Connecticut Technical High School System,” NBER Working Paper (May 2021).