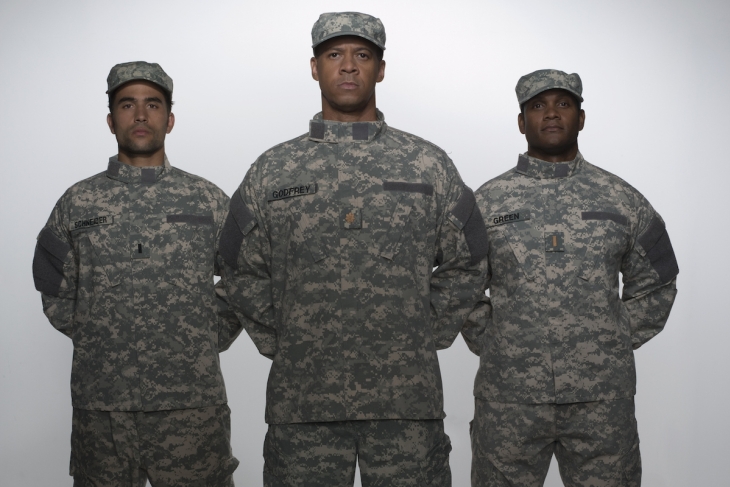

Of the three main postsecondary pathways for American high school graduates—college enrollment, job employment, and military enlistment—the last is arguably least studied in terms of outcomes for those who follow it. A team of analysts led by West Point’s Kyle Greenberg helps fill the void with newly-published research drawing on thirty years of data. Does military service increase opportunity? Does it reduce racial inequality? We might well expect it to, as the stable income and generous benefits (free college tuition among them), skill-building opportunities, and veteran networks for those who serve would seem to be valuable boosts into the middle class and beyond. But long stints separated from family, exposure to combat, and possible permanent injury, disability, or mental health challenges could mitigate or entirely erase any positives accruing from service.

Greenberg and his team use data on the universe of Active Duty Army applicants from 1990–2011, exploiting two different cutoff points on the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), which all applicants are required to take. The Army generally rejects applicants with AFQT scores below the 31st percentile of national math and verbal ability, often requires applicants to score in the 50th percentile or higher to receive enlistment bonuses, and sometimes requires GED recipients to achieve a score in the 50th percentile or higher. Using applicants’ first AFQT scores on file, the researchers find that crossing the 31 and 50 AFQT cutoffs increases the probability of enlistment by 10 and 6 percentage points, respectively. The researchers leverage these cutoffs to estimate the effects of enlistment on earnings and related outcomes for individuals just above and below those cutoffs. Administrative data come from IRS, National Student Clearinghouse, Social Security Administration, and Department of Veterans Affairs records, and are so extensive that Greenberg and his team are able to estimate the direct, causal effect of service not just on earnings and employment, but also on educational attainment, mortality, disability compensation, and more.

Applicants during this period numbered 2.6 million. Overall, they were young (20.7 years) and mostly male (78 percent), and the vast majority (93 percent) had not yet attended college. Compared to the general population, they were more likely to be Black (21 versus 15 percent); less likely to be Hispanic (11 versus 15 percent); and more likely to come from disadvantaged counties in terms of household income, employment, and measures of intergenerational mobility. Applicants came from families with approximately 15 percent lower median income than in a comparable national random sample over the same period.

The applicant sample with AFQT scores close to the two cutoff points comprised about two-thirds of the full population, i.e., 1.8 million individuals. Compared to the full population of applicants, those in the sample have lower average AFQT scores (42 versus 52), are more likely to be Black (26 percent versus 21 percent), and are less likely to have attended college (4 percent versus 7 percent). The average applicant who ultimately served in the Army did so for 4.8 years, which appears to impact the robustness of the outcomes.

Greenberg and his team find that enlisting in the Army increases average annual earnings by over $4,000 in the nineteen years following application. (That’s so at both cutoffs.) The effects of service vary over time, with the largest effects observed in the first four years—that is, higher salaries while serving than they would likely earn in civilian jobs they can get with their age and experience—and smaller effects five to ten years after application. In the longer-term, eleven to nineteen years after application, increases are smaller and statistically insignificant for those at the lower AFQT cutoff and only marginally significant at the higher cutoff.

Short-run employment increases at both cutoff points, but enlistment has no long-run effect on employment at either. Army service, consistent with the generous education benefits provided, considerably increases college attendance at both cutoffs. Army service over the period had no impact on mortality; however, there are large increases in disability compensation. While this raises the monetary return of service in raw numbers, increased health risks can have other costs down the line and may explain some of the long-term effects on income.

However, these general findings mask some far stronger outcomes for Black applicants. The researchers find that enlisting in the Army increases Black applicants’ annual earnings by $5,500 at the 31 AFQT cutoff and by $15,000 at the 50 AFQT cutoff eleven to nineteen years after application. Meanwhile, White applicants actually experience small earning losses at the lower cutoff, which rebound to small gains at the higher cutoff. In fact, compared to their counterfactual earnings trajectories in the sample, Army service closes nearly all of the Black-White earnings gap. Additional benefits which accrue for Black applicants more strongly include homeownership and marriage rates. In looking at mechanisms to explain the substantial positive outcomes for Black enlistees, Greenberg and his team note that Black servicemembers tend to serve longer than their White counterparts and have a higher probability of employment in high-paying industries and/or public service jobs nineteen years after enlisting.

These findings show that enlisting in the Army is a smart pathway for individuals near these AFQT cut-offs to follow. In the short term, their income prospects are far higher than in civilian life—and, as it currently stands, the concern of a higher mortality rate is not borne out. Both short- and long-term benefits accrue to Black enlistees even more strongly than their White peers. And to make sure that those benefits continue and grow following service, the longer an enlistee can serve, the better.

SOURCE: Kyle Greenberg et al., “Army Service in the All-Volunteer Era,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (November 2022).