School options have increased in Ohio and across the nation in recent decades. One prominent option is publicly funded scholarships (or “vouchers”) that families can use to send their children to participating private schools. Today, over 75,000 Ohio students participate in one of the state’s five voucher programs, the largest of which are known as EdChoice. Despite their growing popularity, critics have argued that expanding voucher programs harms traditional school districts. But are they right?

Authored by Ohio State University professor Dr. Stéphane Lavertu, this report explores the impacts of Ohio’s EdChoice program on school district enrollments, finances, and educational outcomes. The study includes detailed analyses of the state’s “performance-based” EdChoice program that, as of 2021–22 provides vouchers to approximately 35,000 students as well as its “income-based” EdChoice program which serves approximately 20,000 low-income students.

Foreword

By Aaron Churchill and Chad L. Aldis

Try saying it with us: “Choice and competition are good.” Don’t take our word alone. On the left, President Joe Biden said:

The heart of American capitalism is a simple idea: open and fair competition—that means that if your companies want to win your business, they have to go out and they have to up their game. . . . Fair competition is why capitalism has been the world’s greatest force for prosperity and growth. [1]

And on the right, President George W. Bush stated:

Free market capitalism is the engine of social mobility—the highway to the American Dream. . . . If you seek economic growth, if you seek opportunity, if you seek social justice and human dignity, the free market system is the way to go. [2]

Their remarks, of course, refer to economic systems writ large, while the report that follows is about primary and secondary education. Even so, in the world of K–12 education, choice and competition are also the way to go. Choice empowers families to select the schools that best fit the needs of their kids, be they district options or alternatives such as public charter schools or private schools. No longer are parents shackled to a singular, residentially assigned, district-operated school that may or may not educate their children to their full potential.

Competition—the other side of the same coin—encourages schools to pay closer attention to the needs of parents and students who, if dissatisfied, can vote with their feet and head for the exits. This sort of “market discipline” helps to promote productive habits and effective practices across both the public and private school sectors.

National polling shows that strong majorities of Americans agree with the intuition behind expanded school choice.[3] Rigorous analyses also reveal benefits to students when states foster choice-friendly environments. Studies on the “competitive effects” of choice programs (both public charter and private school voucher) in states such as Arizona, Florida, and Louisiana have uncovered academic gains for students who stay in traditional public schools.[4] A sweeping national study from our Fordham Institute colleagues in Washington, D.C., found that district and charter students make stronger academic progress when they live in metro areas with more options.[5]

Closer to home, we published a 2016 study by Drs. David Figlio and Krzysztof Karbownik finding that Ohio’s private school voucher program, known as EdChoice, lifted achievement in district schools during its very first years (2006–07 to 2008–09).[6]

So what brings us here again?

In short, the detractors haven’t gone away, the self-interest of the “education establishment” remains strong, and accusations continue to fly that choice programs harm traditional public schools. Here in Ohio, the latest incarnation is the “Vouchers Hurt Ohio” coalition, a group of lobbyists, district administrators, and school boards that have sued the state in an effort to eliminate EdChoice, the state’s largest voucher program, which now serves some 60,000 students. Presently pending before a Franklin County judge, their lawsuit claims that EdChoice hurts district finances and results in more segregated public schools. Though not expressly stated, their claims imply that district students themselves may also be harmed academically.[7]

The plaintiffs build their case around basic school funding and demographic statistics. Their numbers, however, cannot prove cause and effect. For instance, as evidence of segregation, they cite data from the Lima School District, which enrolled 54 percent students of color pre-EdChoice, a number that has since risen to 65 percent. Their implication is that EdChoice is responsible, but they ignore even the possibility that this trend could reflect larger demographic shifts that are entirely unrelated to vouchers (e.g., White families exiting the district and/or minority families moving in). Unless one conducts rigorous analyses that separate the impacts of EdChoice from other factors, superficial statistics are apt to mislead.

To conduct a more careful investigation of the impacts of EdChoice, we turned to Stéphane Lavertu of The Ohio State University. He is a fine scholar, with a strong track record of evaluating various school choice and accountability initiatives in the Buckeye State. His work includes a widely cited national evaluation of charter school performance for the RAND Corporation, along with numerous studies on local school governance and policy that have appeared in peer-reviewed academic outlets such as the Journal of Public Economics, American Political Science Review, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, and Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

The truth of the matter turns out to be far different than the critics’ claims. In studying the state’s performance-based EdChoice program[8] from inception to the year just prior to the pandemic (2006–07 to 2018–19), Dr. Lavertu uncovers the following:

- Improved district achievement. Importantly, he finds that EdChoice did not harm district students and, in fact, led to modest achievement gains. Although affected districts still tend to struggle overall academically, these incremental improvements suggest that a more competitive environment may have helped focus districts on academic success. The results here are consistent with other studies, including the aforementioned Ohio analysis by Figlio and Karbownik, showing a positive influence of choice programs on district performance. Yes, that is right: a positive influence on district achievement, even as some students depart for private alternatives.

- Reduced district segregation. Due to their geographic boundaries and residential patterns, Ohio school districts were highly segregated long before vouchers existed. Fortunately, EdChoice has helped to lessen district segregation—no doubt reflecting the strong participation of Black and Hispanic students in the program (55 percent of voucher recipients in 2018–19). With such large numbers of Black and Hispanic students moving to the private school sector, the likelihood that public school students are in a racially “isolated” school has declined.

- No impact on district expenditures per pupil. Contrary to the critics’ chief allegation—that vouchers “drain money” from districts—EdChoice does not decrease the per-pupil expenditures of districts. The neutral fiscal impact should be expected. While seeing reductions in state aid when students participate in choice programs, districts experience an increase in local funding per pupil, because those taxpayer dollars do not “follow” voucher (or charter) students to their schools of choice.

The available data did not allow Dr. Lavertu to draw clear conclusions about the causal impact of income-based EdChoice, which bases voucher eligibility on family income.[9] That being said, the evidence—circumstantial as it may be—indicates that this newer program (launched in 2013–14) has no adverse impact on districts.

“The sky is falling,” cry the Chicken Little critics of Ohio’s choice programs. But they are mistaken. District students are not left as “collateral damage” when parents have more education options and decide to pursue them. Quite the contrary: the increased competition seems to stir traditional public schools to undertake actions that benefit district students. For judges, journalists, and Ohioans everywhere, we say this: don’t believe the critics’ hype. And for Ohio policymakers, we say: keep working to expand quality educational choices. Free and open competition is known to fuel economic growth. In the same way, it can also drive excellence, innovation, and greater productivity in our public and private schools.

Executive summary

Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program (EdChoice) is the state’s largest voucher program. It provides state funds to cover all or part of private school tuitions for eligible students. Since the 2006–07 school year, the original EdChoice program—known as “performance-based EdChoice”—has provided scholarships to families whose children attend traditional public schools that the state deems to be poorly performing. And since 2013– 14, the EdChoice expansion program—known as “income-based EdChoice”—has provided scholarships to low-income families whose children do not qualify for the performance-based program.

The central purpose of EdChoice is to provide more educational options for economically or educationally disadvantaged students. Another purpose is to introduce competition into the education system to incentivize improvement in traditional public schools, thereby also benefiting students who do not participate in the program. Although earlier research has found some evidence of positive competition-related effects in the initial years of the performance-based EdChoice program, a recent lawsuit claims that Ohio’s EdChoice programs have harmed district finances, contributed to racial segregation, and undermined the education of district students. The purpose of this report is to determine what discernible effects EdChoice has in fact had on Ohio districts as its programs have expanded.

We estimate the impact of the EdChoice programs by comparing changes in district outcomes (from before these programs were in place to the 2018–19 school year) between districts that had higher as opposed to lower levels of exposure to them. Research demonstrates that such comparisons can allow one to estimate the causal impact of a policy if certain assumptions are met. As we detail in the report, our analysis of the performance-based EdChoice program arguably satisfies those assumptions and, thus, enables us to make claims about its causal impact on Ohio school districts. Unfortunately, our analysis of income-based EdChoice reveals that the research design’s assumptions are unlikely to hold. Consequently, when it comes to income-based EdChoice, we can speak only to the relative changes in outcomes for districts with higher (as opposed to lower) levels of exposure to the program. We cannot claim that income-based EdChoice caused those relative changes.

Here, in brief, are our estimates of the performance-based EdChoice program’s impact as of 2019 (thirteen years after the program’s start in the fall of 2006) on the average public school district exposed to it:

- District enrollments were approximately 10–15 percent lower than they would have been had districts not been exposed to the program. These effects are driven by relative declines in the enrollment of Black students, not Asian American, Hispanic, or White students.

- Racial and ethnic segregation was approximately 10–15 percent lower than it would have been had districts not been exposed to the program. Specifically, as a result of the EdChoice program, Black, Hispanic, and Native American students attended schools with a greater share of White and Asian American students than they would have in the absence of the program.

- Total district spending per pupil (including both capital outlays and operational spending) was no different than it would have been had districts not been exposed to the EdChoice program. There is suggestive evidence that the program in fact led to a relative increase in districts’ operational spending per pupil. That is because EdChoice had no impact on districts’ ability to raise local revenue. Combined with the decrease in enrollments, this dynamic led to a 10–15 percent increase in local revenue per pupil. Consistent with these estimates, the analysis reveals no statistically significant impacts on district property values, local property tax rates, local property tax revenues, levy passage rates, or state-defined fiscal stress designations.

- The academic achievement of district students—as measured by the state’s performance index—was significantly higher than it would have been had districts not been exposed to the EdChoice program. For the average student in a district exposed to performance-based EdChoice, their district’s achievement went from approximately the second percentile (the twelfth-lowest-achieving Ohio district) to approximately the sixth percentile (the thirty-seventh-lowest-achieving Ohio district). This effect is consistent with the program targeting low-achieving schools, thus increasing average district proficiency rates among remaining students. The results are also consistent with a rigorous study indicating that the competitive pressures of performance-based EdChoice had a null or positive impact on Ohio’s traditional public schools during the program’s early years.[10]

As for the income-based EdChoice program, we noted above that the estimated impacts on districts are more suggestive than causal. A basic comparison of pre- and post-program outcomes indicates that, by 2019, districts more exposed to the program (by virtue of having higher poverty rates) experienced relative declines in enrollments; relative declines in racial and ethnic segregation; no statistically significant changes in total expenditures; relative increases in operational expenditures per pupil; relative increases in local revenue per pupil; and no statistically significant changes in student achievement. However, estimated changes in enrollments and segregation are highly sensitive to model specification and, thus, a causal interpretation of these findings is particularly suspect.

Overall, the analysis provides solid evidence that the performance-based EdChoice program led to racial integration, had no adverse effects on revenues per pupil, and increased student achievement in public school districts. It also reveals no credible evidence that the income-based EdChoice expansion harmed districts in terms of segregation, revenues, or student achievement. Thus, although EdChoice-eligible schools have indeed experienced increases in racial segregation and declines in achievement, these trends began well before 2006 and should not be attributed to private school vouchers. Instead, the analysis indicates that these long-term trends in district segregation and achievement would have been worse in the absence of the performance-based EdChoice program.

Introduction

School options have increased in Ohio and across the nation. Most prominent are public charter schools, which operate independently of school districts and now educate approximately 7 percent of Ohio students. Another prominent option is publicly funded scholarships (or “vouchers”) that families can use to send their children to participating private schools. Although involving fewer children than charter schools, participation in Ohio’s several voucher programs has risen significantly—particularly during the pandemic, when many families sought in-person schooling options for their children and found them more readily available in private schools.[11] Today, over 4 percent of school-aged children in Ohio participate in one of Ohio’s five voucher programs.

Three quarters of voucher recipients participate in EdChoice, which provides state funds to cover all or part of private school tuition for eligible students. Since the 2006–07 school year, the original EdChoice program—known as “performance-based EdChoice”—has provided scholarships to families whose children attend traditional public schools that the state deems to be poorly performing. And, since 2013–14, the EdChoice expansion program—known as “income-based EdChoice”—has provided scholarships to low-income families whose children do not qualify for the performance-based program. Today, the performance-based and income-based EdChoice programs account for approximately 50 percent and 25 percent, respectively, of total voucher participation in Ohio.[12]

Although there is significant public support for publicly funded vouchers,[13] rigorous evidence of their impact is mixed. Evaluations of the early implementation of urban voucher programs in Milwaukee and Washington, D.C., indicate small positive effects on program participants’ achievement (i.e., test scores) and attainment (i.e., level of education, such as graduation from high school or college attendance).[14] On the other hand, more recent evaluations of expanded voucher programs in Indiana, Louisiana, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., indicate significant negative impacts on participants’ test scores.[15] Beyond academic impacts on program participants, studies almost always indicate that parents who use vouchers report greater satisfaction with the quality and safety of their children’s schools.[16]

Criticisms of vouchers often center on their purported negative effect on traditional public schools. One contention is that vouchers siphon from school districts relatively high-achieving students whose families are more affluent and motivated, leaving behind concentrations of relatively disadvantaged, low-achieving, or minority students in traditional public schools. A related argument is that, because districts lose the state per-pupil funding tied to students who leave public schools with the help of vouchers, they have fewer resources to educate students who remain. Critics contend that these dynamics, in turn, lower the educational quality of public schools. The available research, however, suggests the opposite is true. There is rigorous evidence that voucher programs in Milwaukee and Florida led to improvements in the achievement of students who remained in traditional public schools, apparently because the competition that comes with the availability of vouchers incentivized traditional public schools to improve their performance.[17] An earlier Fordham-sponsored study also provides rigorous evidence that Ohio’s performance-based EdChoice program had no negative impact—and perhaps a positive impact—on the achievement of district students whose schools faced competitive pressure beginning in 2007–08.[18]

Although the Fordham study indicates that the performance-based EdChoice program did not harm the district schools that faced such competitive pressure during the program’s initial years, we do not know the district-wide and long-term impacts of the program on student achievement. Similarly, although the earlier study reveals that, among eligible students enrolled in district schools, participation rates differed substantially by family income levels and prior pupil achievement (but not by race), we do not know the impacts on district-wide enrollments and student segregation. As we discuss below, voucher programs may have impacts on district enrollments and finances that are more pronounced than one would expect based on the number and characteristics of voucher users. One reason is that districts’ enrollments and ability to raise local revenue via taxes are driven in part by their desirability as a place to live—something which voucher programs can affect in a variety of ways. To our knowledge, however, no rigorous evaluation of voucher programs—in Ohio or elsewhere—has estimated comprehensive, district-wide impacts of publicly funded vouchers on public school districts’ enrollments, finances, and educational outcomes.

The purpose of the present study is to estimate the effects of Ohio’s EdChoice programs on district enrollments, finances, and educational outcomes using a rigorous quasiexperimental approach and the best data available. We begin with a description and analysis of the performance-based EdChoice program—the larger of the two programs and the one for which our research design generates plausibly causal impact estimates. Then we describe and provide suggestive evidence of the impact of the income-based program. We conclude with key takeaways.

Performance-based EdChoice

The Ohio General Assembly enacted the performance-based EdChoice program in June 2005. At the start, it made available scholarships (vouchers) of up to $4,250 for elementary school students and $5,000 for high school students, provided that they had been assigned to schools considered poorly performing and did not reside in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (whose students were already eligible for state-funded vouchers). Ohio law initially defined poorly performing schools as those with an “academic emergency” rating, Ohio’s lowest mark, for three consecutive years. Lawmakers relaxed those criteria in March 2006 and again in December 2006. These changes extended eligibility to students enrolled in district schools receiving “academic watch” ratings—the state’s second lowest—or worse in two of the previous three school years.

Although Ohio’s school-rating methodology and the districts with eligible schools (and thus eligible students) would change somewhat in subsequent years, the number of districts with EdChoice-eligible schools remained fairly stable from 2006–07 to 2018–19 (the last year of our analysis). Specifically, as Table 1 indicates, in each of those years about thirty districts had an average of seven to eight schools on the EdChoice eligibility list. But this apparent stability masks the number of districts exposed to the program, as some districts with few schools on the list—and, thus, few eligible students—rolled on and off the list from year to year. Indeed, by the 2015–16 school year, forty-seven districts had at least one school on the list for at least one year. The increased pool of EdChoice-exposed districts led program participation to grow from 3,071 in its first school year of operation (2006–07) to 23,482 during the 2018–19 school year.

Table 1. Districts with eligible schools and performance-based EdChoice participation

Note. All figures are calculated based on data on the ODE website. School years are denoted by the spring calendar year (e.g., 2007 refers to the 2006–07 school year). Participant counts by district were unavailable for earlier years, so we report statewide participation counts. The table excludes a sizable jump in districts with eligible schools and program participation that occurred after 2019, as those years are not part of our analytic sample.

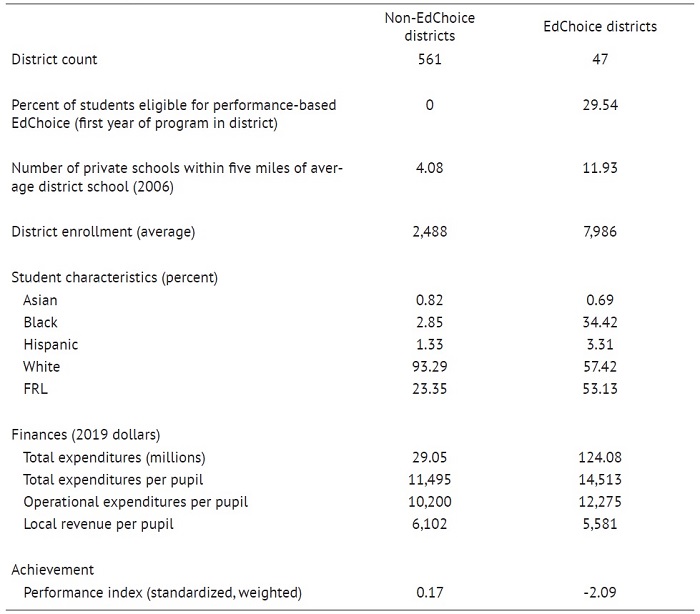

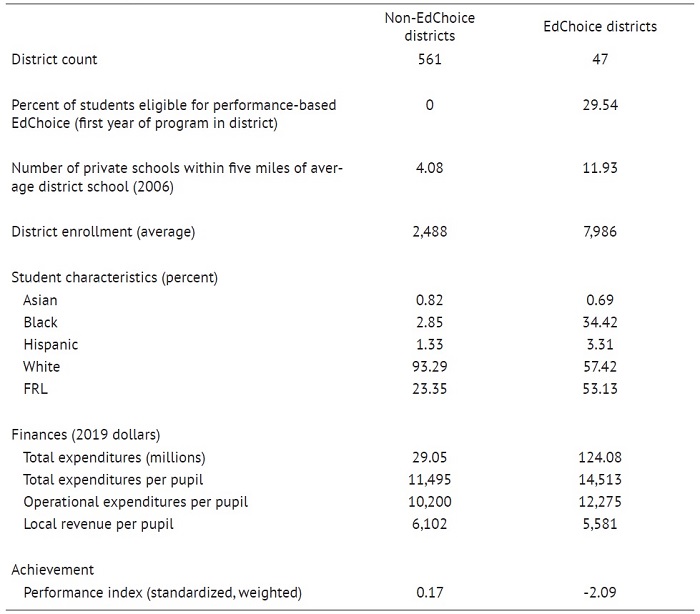

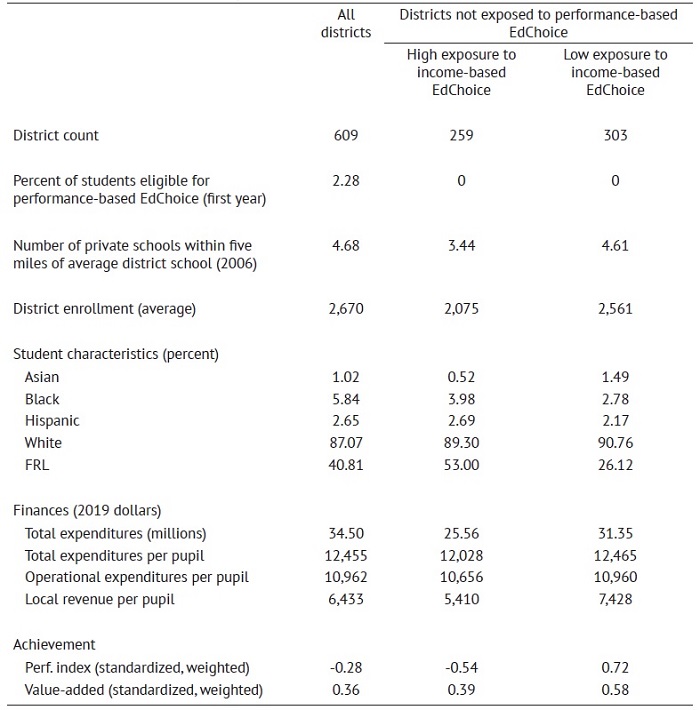

Note. All figures are calculated based on data on the ODE website. School years are denoted by the spring calendar year (e.g., 2007 refers to the 2006–07 school year). Participant counts by district were unavailable for earlier years, so we report statewide participation counts. The table excludes a sizable jump in districts with eligible schools and program participation that occurred after 2019, as those years are not part of our analytic sample.The performance-based EdChoice program’s focus on the state’s lowest-rated schools meant that districts exposed to the program served largely disadvantaged students. Table 2, below, compares the forty-seven districts exposed to the program (at any time from 2006–07 through 2018–19) to the average Ohio district. Just prior to the program’s start, during the 2004–05 school year, students in districts that became exposed to EdChoice had been disproportionately economically disadvantaged (53 percent of district students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches (FRL) versus 23 percent in districts without EdChoice-eligible buildings); Black (34 percent versus 3 percent); and Hispanic (3 versus 1 percent).[19] Predictably, exposed districts were also the lowest performing. The average student in an EdChoice-exposed district was in a district that was over two standard deviations below the statewide average (approximately the second percentile among all Ohio districts) on the Ohio performance index, a composite measure that aggregates student performance on state tests across all subjects and grades.

Table 2 also reveals that districts exposed to the performance-based EdChoice program between 2006–07 and 2018–19 were large, with average enrollments in 2004–05 of almost 8,000 students (versus 2,500 in other districts) and which spent more per pupil ($14,500 per pupil in 2019 dollars versus $11,500) despite performing worse academically.[20] They also had a higher concentration of private schools prior to the program’s implementation: approximately twelve private schools within five miles of the average district school, as opposed to four in districts not exposed to EdChoice. Thus, when about one-third of students in the average EdChoice-exposed district suddenly qualified for the program, there were likely private schools for them to attend. Indeed, in some supplementary analyses, we found that the count of private schools near district schools prior to the program’s implementation explained about 80 percent of program participation in 2019. In other words, the significant presence of private schools in these districts before the performance-based EdChoice program’s start made it highly likely that these districts would immediately feel competitive pressure when one or more of their schools made it onto the list.

Table 2. Comparing districts exposed to performance-based EdChoice to those not exposed

Note. Data are from the websites of the National Center for Education Statistics, the Urban Institute, and the Ohio Department of Education. All statistics are from the 2004–05 school year—the year just prior to the enactment of the EdChoice program—unless otherwise noted. We provide statistics from the 2004–05 school year because that is the last year prior to the program’s implementation, which began with a release of EdChoice-eligible schools during the 2005–06 school year. The 2004–05 school year serves as the appropriate baseline for our analysis because statistics from those years are not contaminated by the impact of the program. We inflated financial variables to 2019 dollars using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Personal Consumption Expenditures Price index. The sample is limited to the 608 districts for which we have complete data and omits the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (as, prior to EdChoice, Ohio created a voucher program specifically for students living in that district).

Note. Data are from the websites of the National Center for Education Statistics, the Urban Institute, and the Ohio Department of Education. All statistics are from the 2004–05 school year—the year just prior to the enactment of the EdChoice program—unless otherwise noted. We provide statistics from the 2004–05 school year because that is the last year prior to the program’s implementation, which began with a release of EdChoice-eligible schools during the 2005–06 school year. The 2004–05 school year serves as the appropriate baseline for our analysis because statistics from those years are not contaminated by the impact of the program. We inflated financial variables to 2019 dollars using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Personal Consumption Expenditures Price index. The sample is limited to the 608 districts for which we have complete data and omits the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (as, prior to EdChoice, Ohio created a voucher program specifically for students living in that district).

Analytic strategy

To estimate the causal impact of performance-based EdChoice, it is tempting to compare the enrollments, finances, and academic outcomes of districts that were exposed to EdChoice to districts never exposed to the program. Unfortunately, such a comparison can be misleading, as these districts differed in a number of ways. Indeed, as we show in Appendix A, districts exposed to EdChoice—compared to districts that were never exposed—were experiencing relative declines in enrollments, relative increases in the share and isolation of Black and Hispanic students, relative increases in expenditures, and relative declines in student achievement. A naïve comparison of EdChoice and non-EdChoice districts, therefore, might falsely attribute to the program the continuation of such differential trends after the program’s introduction, when in fact they were already occurring before EdChoice commenced.[21]

To address this problem, our analysis focuses on the forty-seven districts that had at least one building on the EdChoice list between the 2006–07 and 2018–19 school years. These districts are more similar to one another—after all, they all had at least one school that rated sufficiently poorly to qualify for the program. It is more plausible, therefore, that these districts would have had comparable trends in outcomes in the absence of the program. Indeed, as we show in Appendix A, these districts generally had comparable trends in enrollments, finances, and achievement in the years leading up to the program—regardless of the number of district students who qualified for EdChoice—which gives us some confidence that trends would have continued to be similar in the absence of the program.

Specifically, we estimate the impact of performance-based EdChoice by comparing changes in district outcomes—changes from before the program was in place to the 2018–19 school year—between districts that had higher as opposed to lower levels of exposure to the program. Among the forty-seven districts that had schools on the EdChoice list, the average district had 29.54 percent of its students enrolled in eligible schools during their first year. Exposure ranged from districts having 2.6 percent to 100 percent of their students eligible in that first year. Districts with low initial exposure sometimes exited the list in subsequent years, whereas those with a higher percentage of eligible students tended to stay on across all years. Thus, these forty-seven districts capture a wide range of exposure to the program.

Our measure of exposure is based on initial program exposure because enrollment counts after 2005–06 are themselves influenced by the program. For example, if students exit schools eligible for EdChoice, future program exposure would appear lower than it is. Thus, for the thirty-three districts with students participating in the program during the 2006–07 school year (the first year of the program), our measure of program exposure for all years is based on the enrollment data from the 2005–06 school year. We do the same for districts that were first exposed in subsequent years. For example, if a district first had participating students during the 2014–15 school year, we calculated exposure based on enrollment data during the 2013–14 school year.[22]

This method effectively entails calculating changes in outcomes between the 2004–05 and 2018–19 school years for each of the forty-seven districts exposed to the program, then comparing those changes in outcomes between districts with different levels of exposure to the program (based on the exposure measure we describe above).[23] We use the 2004–05 school year as the baseline because it predates the enactment of the program in June 2005. We focus on effects through 2018–19 because it was the last school year for which we had values for all enrollment, finance, and achievement outcomes. The 2018–19 school year also turned out to be a good terminal year because of significant changes in EdChoice exposure in 2020, as well as the pandemic’s multiple effects on district enrollments, finances, and testing.

The raw estimates from our statistical models indicate how much one additional percentage-point increase in exposure to EdChoice affected outcomes up to thirteen years later, depending on when a district was first exposed. For ease of interpretation, the figures below report effects as percent changes in an outcome (compared to the 2004–05 baseline) for the average district with an EdChoice-eligible school. We encourage readers to consult Appendix A to review the raw statistical results as well as the results of validity and sensitivity tests. Notably, as we mention above, these tests reveal minimal differences in trends in the years leading up to the program (1998–99 through 2004–05) between districts that would ultimately have high as opposed to low levels of exposure to the program after 2005. It is these additional analyses that lead us to treat our estimates as capturing the plausibly causal impacts of district exposure to the performance-based EdChoice program.

In the following subsections, we review our primary estimates of the impact of performance-based EdChoice on district enrollments, racial and ethnic segregation, finances, and achievement. The enrollment, spending, and revenue data are from the websites of the National Center for Education Statistics and the Urban Institute. The tax and property valuation data are from the Ohio Department of Taxation website and the referendum data are from the lead author.[24] Financial variables are expressed in 2019 dollars and were adjusted for inflation. The performance index since 2005–06 is from the Ohio Department of Education’s website. The performance index from earlier school years comes from archived records related to the No Child Left Behind accountability system.

Enrollments

The performance-based EdChoice program could have affected district enrollments in multiple ways. The most direct way was through program participation, as any district student who used a voucher to attend a private school was no longer enrolled in that district. If that were the sole mechanism, district enrollments would have declined by one student for every voucher participant who resided in that district. But the program could also have affected district enrollments in other ways. For example, if publicizing the list of schools eligible for EdChoice led families to perceive district schools as poorly performing, then they may have taken advantage of other schooling options (e.g., charter schools) or moved to another district. Indeed, families may have reacted this way even if their children were attending district schools that were not on the list, and families living outside the district may have been less likely to move to the district. On the other hand, if EdChoice led to improvements in the performance of district schools (e.g., through competitive pressures), then families might have become attracted to the district and enrollments might have increased. Our research design should capture all such downstream consequences.

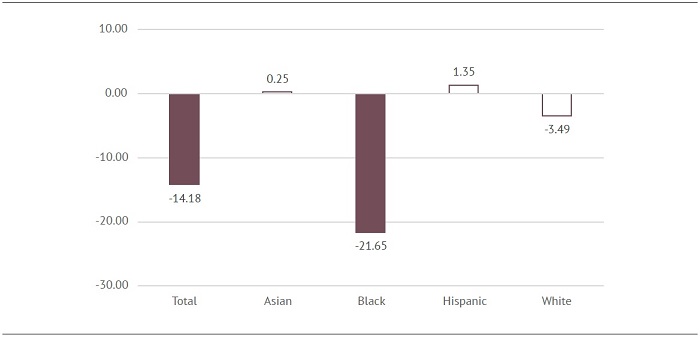

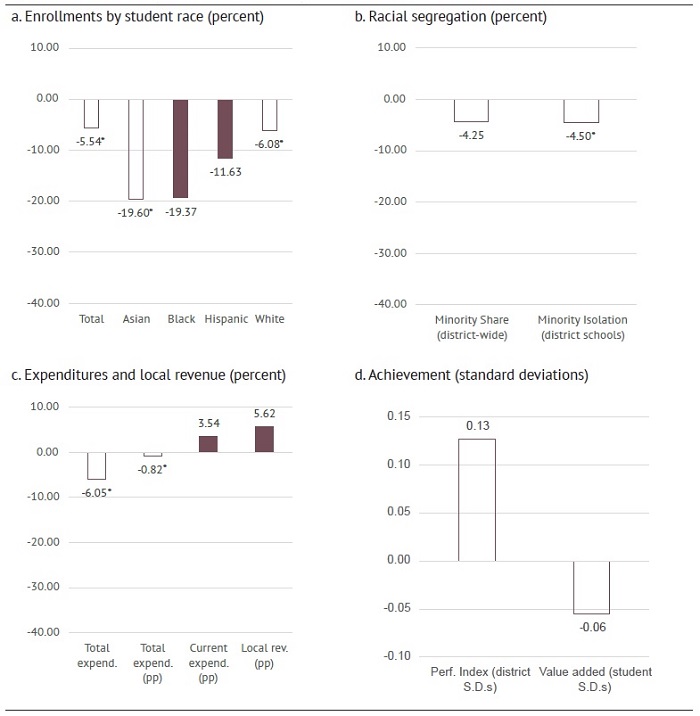

Indeed, the results of our analysis indicate that performance-based EdChoice affected district enrollments more than actual program participation counts suggest. As Figure 1 (below) shows, the average district with EdChoice-eligible schools between 2006–07 and 2018–19 experienced a relative decline in enrollment of 14 percent as a result of the program. As we show in the appendixes, the exact estimate is somewhat sensitive to model specification, but it is fair to say that the average district participating in the performance-based EdChoice program had approximately 10–15 percent fewer students in 2018–19 than it would have had in the absence of the program. Across all EdChoice-exposed districts statewide, that estimate implies a relative decline of approximately 35,000 to 55,000 students. Actual program participation in 2018–19 was 23,482 (see Table 1). Thus, even the lower end of our estimates implies that districts with EdChoice-eligible buildings experienced relative declines that exceeded what one would have expected based on actual program participation.

Figure 1 also indicates that these relative declines in enrollment are driven primarily by declines in the enrollment of Black students. We estimate that EdChoice led to a relative decline in district-enrolled Black students of approximately 20 percent. For the average EdChoice district, that equates to the share of Black students enrolled in its schools shrinking from approximately 34 percent to approximately 27 percent. It is understandable that Black students would take greater advantage of vouchers, as EdChoice-eligible schools served mostly Black students. But these results are nonetheless inconsistent with what one would have expected based on actual program participation. Though our results indicate that nearly 100 percent of relative declines in district enrollment are driven by Black students, 43 percent of official program participants in 2019 were Black, whereas 35 percent were White.

One possibility is that White families who participated in the program were more likely to have sent their kids to private schools even in the absence of the program. In other words, data on voucher recipients might include White students who would not have attended district schools even in the absence of the program, so their participation in the program would not have affected the counts of White students in the district (as per the results in Figure 1). Indeed, these White students’ families might have moved to the district—or stayed in the district—because vouchers were an option. On the other hand, it may be that Black EdChoice participants would have attended district schools, such that their participation in the program affected district enrollments (as per the results in Figure 1). And, as we note above, a signal of poor district performance (the EdChoice school eligibility list) might have led families of Black students to send their children elsewhere (such as charter schools), which would have led to an even more pronounced decline in the share of district students who are Black than program participation implies. Thus, one way to reconcile differences in the race and ethnicity of EdChoice participants with changes in the racial and ethnic composition of district students is that White program participants might have been less likely to attend district schools in the first place (these students were never districts’ to lose), and Black students may have been more likely to exit district schools for other educational options such as private and charter schools.

Figure 1. Percent changes in district enrollments by student race

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on enrollments as a percent of enrollments prior to the start of the program in 2004–05. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact on district enrollments, and bars below zero indicate a negative impact. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on enrollments as a percent of enrollments prior to the start of the program in 2004–05. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact on district enrollments, and bars below zero indicate a negative impact. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.It is important to note that the estimates for White and Hispanic students are not statistically significant, but we cannot rule out substantively significant increases or declines in their enrollments because our estimates are imprecise. Similarly, we cannot rule out that relative declines in enrollments match participation counts exactly. That is because there is random error in statistical estimates (e.g., margins of error in public opinion polls). What we can say is that the estimated enrollment declines—overall and for Black students in particular—are unlikely to be due to chance. We can also say that our best estimate is that the share of Black district students was lower (and the share of White district students higher) than one would have expected based on the demographics of program participants.

Segregation

According to 2018–19 ODE data, students participating in the performance-based EdChoice program were 43 percent Black, 35 percent White, 12 percent Hispanic, 2 percent Asian American, and 1 percent American Indian or Alaskan Native. Thus, statewide, approximately 56 percent of voucher participants were Black, Hispanic, or American Indian or Alaskan Native, which are the minority racial and ethnic groups (“minority students” from now on) on which researchers focus when assessing the extent to which schools are segregated. Put differently, these data indicate that private school vouchers disproportionately go to minority students. However, as we discuss above, such data on voucher participants do not provide a good approximation of how performance-based EdChoice affected district enrollments—let alone how students were distributed across schools in those districts. The purpose of this analysis is to provide a valid estimate of performance-based EdChoice’s impact on the segregation of minority students in district schools.

We estimated the impact of performance-based EdChoice on racial and ethnic segregation among district schools using the same research design we used for enrollments, this time comparing changes in segregation (from 2004–05 to 2018–19) between districts with different levels of initial exposure to the program. Another difference between this analysis and the enrollment analysis is that we now weight statistical models by the number of students in a district, as that allows us to characterize the average level of segregation students experienced across the forty-seven EdChoice-eligible school districts.[25] The intuition is that the extent to which a given district’s segregation figures into our estimates should be proportional to the number of students experiencing that segregation.[26]

There are commonly accepted ways of measuring student segregation across district schools.[27] To simplify the exposition, we focus on one of these measures: the isolation of minority students in particular schools. Specifically, our segregation measure captures the share of minority students in the average minority student’s school.[28] Another way to think about it is that the measure captures the probability that a minority student will be exposed to other minority students, as opposed to nonminority students. In the appendix, we also present the results using other measures of segregation prominent in the academic literature. We describe those measures in Table C1 of Appendix C. As we show in Figure C1 in that appendix, those other measures yield similar estimates, which further validates our main findings and empirical design.[29]

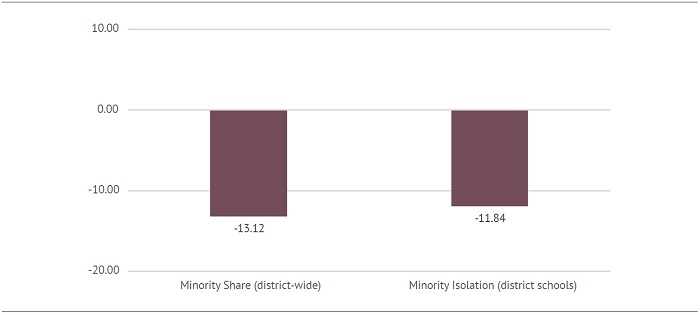

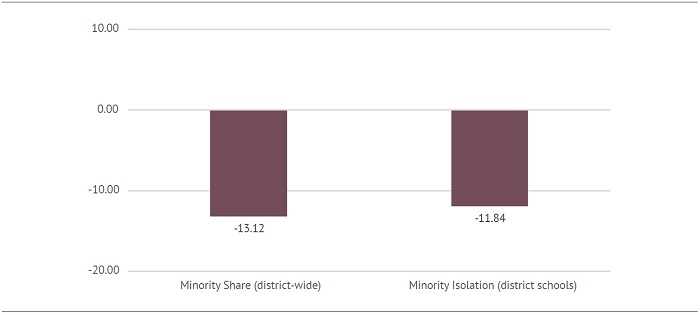

Before we turn to EdChoice’s impact on minority student isolation, Figure 2 (below) reveals that the average student whose district was exposed to the program experienced a relative decline of approximately 13 percent in the district-wide share of students who identify as a racial or ethnic minority (Black, Hispanic, or Native American). During the 2004-05 school year, the average student was in a district in which 49 percent of students identified as a minority (see Table C1 in Appendix C). [30] A 13 percent decline is equivalent to going from 49 percent to 43 percent. Thus, consistent with our enrollment results above, for the average student in our sample, EdChoice led to a decline of six percentage points in the share of minority students districtwide.

Turning to our measure of school-level district segregation, Figure 2 indicates that EdChoice led to a decline of 12 percent in the isolation of minority students. During the 2004–05 school year, the average minority student was in a school in which 57 percent of students identified as a minority (see Table C1 in Appendix C). A 12 percent decline is equivalent to going from 57 percent to 50 percent. Thus, it appears that the relative reduction in the district-level share of minority students indeed led to a comparable reduction in the school-level isolation of minority students. Put differently, the estimates indicate that because of EdChoice, Black, Hispanic, and Native American students went to schools with a greater share of White and Asian American students than they would have in the absence of EdChoice. As we note above and show in Appendix C, other measures of segregation yield similar effect sizes.[31]

Figure 2. Percent change in the share and isolation of minority students

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on the segregation of Black, Hispanic, and Native American students as a percent of the baseline value of the segregation measure in 2004–05. The measures of segregation are the share of district students who identify as underrepresented minority students and the isolation of minority students in particular district schools. Bars below zero indicate that the program reduced segregation. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on the segregation of Black, Hispanic, and Native American students as a percent of the baseline value of the segregation measure in 2004–05. The measures of segregation are the share of district students who identify as underrepresented minority students and the isolation of minority students in particular district schools. Bars below zero indicate that the program reduced segregation. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.

Finances

The EdChoice program is funded by the state, and state per-pupil funding is what districts stand to lose when a student exits their schools to participate in the voucher program. But districts with EdChoice students retain all the revenue they generate locally via property and other taxes.[32] As Table 2 shows, as of the 2004–05 school year, local revenue accounted for approximately 40 percent of total revenue among districts exposed to performance-based EdChoice between 2006–07 and 2018–19. Thus, simple logic suggests that a decline in enrollment due to program participation would lead to an increase in per-pupil district revenue that is easy to calculate, since districts would only lose the state share for each student. Although that intuition ultimately proves useful, the underlying reality is more complicated.

One reason this intuition is not quite right is that the direct cost to individual districts from having students participate in the program depended on how much state money they received in complicated state formulas that changed often between 2006–07 and 2018–19.[33] Another reason is that, as we show in the enrollment analysis, the relative enrollment declines associated with the program appear to be greater than program participation numbers. Finally, a simple accounting of voucher costs and total enrollment effects (like those we document above) does not account for the EdChoice program’s impact on districts’ ability to bring in local revenue. For example, what if the annual release of the list of EdChoice-eligible schools reminded district residents of the poor performance of their schools and led them to vote down district tax referenda? What if the availability of vouchers meant that districts attracted more affluent families who pay higher taxes? Once again, the possibilities are many, and our research design is meant to take into account the totality of the performance-based EdChoice program’s impact on district finances.

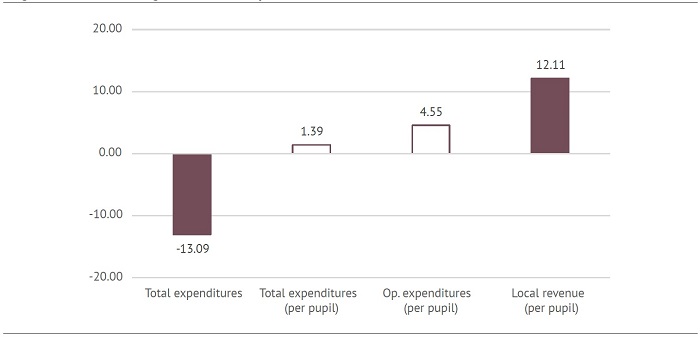

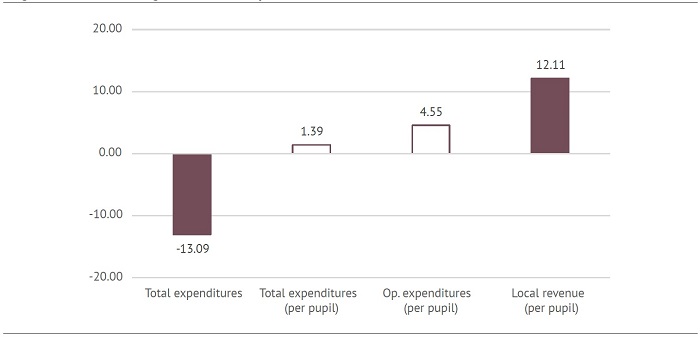

Nonetheless, the results in Figure 3 (below) tell a basic overall story that is remarkably consistent with intuition regarding EdChoice’s impact on district finances. The figure reveals that, for the average district exposed to performance-based EdChoice, the program led to a decline of approximately 13 percent in total expenditures—expenditures not reported on a per-pupil basis. However, on a per-pupil basis, we estimate that performance-based EdChoice led to an increase in total expenditures per pupil of 1.39 percent and an increase in operating (noncapital) expenditures of 4.55 percent per pupil. These last two results do not attain conventional levels of statistical significance—though the estimate for operating expenditures comes close in some specifications—but they do enable us to essentially rule out a long-term decline in per pupil expenditures. The estimates in the appendix also reveal statistically significant increases in current expenditures per pupil in the short term, just a few years after the program’s introduction (see Figure A4 in Appendix A). This finding may be due to budgetary practices during initial implementation that were meant to compensate districts for potential disruptions as they adjusted to lower enrollments.[34]

Figure 3. Percent changes in district expenditures and local revenue

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on total expenditures (operational and capital), total expenditures per pupil, current (operational) expenditures per pupil, and local revenue per pupil as a percent of expenditures or revenues prior to the start of the program in 2004–05. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact on district expenditures/revenues, and bars below zero indicate a negative impact. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on total expenditures (operational and capital), total expenditures per pupil, current (operational) expenditures per pupil, and local revenue per pupil as a percent of expenditures or revenues prior to the start of the program in 2004–05. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact on district expenditures/revenues, and bars below zero indicate a negative impact. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.Figure 3 also indicates a statistically significant 12 percent increase in local revenue per pupil. In other words, the voucher-related decline in enrollment led to a proportional increase in locally generated district revenue per pupil. That suggests that there was no decrease in EdChoice-exposed districts’ ability to generate local revenue. Indeed, as we show in additional analyses in the appendixes, there are no statistically significant estimated impacts on district property values, local property tax rates, local property tax revenues, levy passage rates, or state-defined fiscal stress designations (see Table A4 in Appendix A). Indeed, the coefficients—though not statistically significant—point toward districts potentially having higher property values, a higher referendum passage rate, and a lower probability of receiving a fiscal stress designation. Thus, the intuition works: declines in enrollments led to increases in revenue per pupil because EdChoice had no negative impact on districts’ ability to raise local revenue.

Achievement

Publicly available data enable us to estimate the impact of performance-based EdChoice on the academic achievement of district students. Specifically, we use Ohio’s “district performance index,” which combines into a single measure the proficiency level of district students across all subjects and tested grades. Because the tests that factor into the index changed significantly over time, we standardized the measure by year so that it captures how many standard deviations away an EdChoice district is from the statewide district average for a given year. Finally, like the segregation analysis, we weighted the statistical models so that we are capturing effects for the average student in a district exposed to performance-based EdChoice.

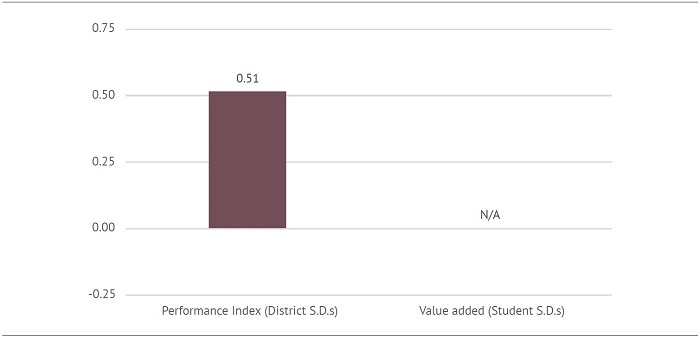

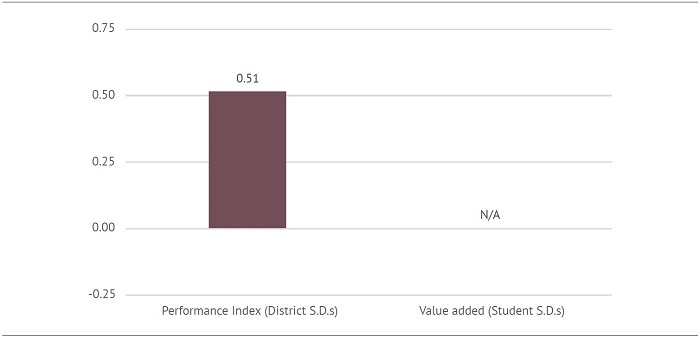

Figure 4. Impact on student achievement (district-level standard deviations)

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on a district’s performance index in district-level standard-deviation units. We are unable to generate similar estimates for annual “value-added” student learning gains because we lack test data prior to the program’s implementation. Estimates are weighted by district enrollment. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact on student achievement. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.

Note. The figure presents the estimated impact of performance-based EdChoice on the average district exposed to the program between 2004–05 and 2018–19. Specifically, it presents the estimated impact on a district’s performance index in district-level standard-deviation units. We are unable to generate similar estimates for annual “value-added” student learning gains because we lack test data prior to the program’s implementation. Estimates are weighted by district enrollment. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact on student achievement. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test.Figure 4 reveals that exposure to EdChoice led to increases in academic achievement in the average student’s district. Specifically, the average student in an EdChoice district experienced an increase in districtwide achievement of half of a standard deviation. That means that the academic achievement of their district went from the second percentile (approximately the twelfth-lowest-achieving Ohio district) to the sixth percentile (approximately the thirty-seventh-lowest-achieving Ohio district).[35] This effect is consistent with the program drawing disproportionately economically disadvantaged students who tend to be low achieving, thus increasing average district proficiency rates.[36] The results are also consistent with a rigorous study indicating that the competitive pressures of Ohio’s performance-based EdChoice have had a null or positive impact on Ohio’s traditional public schools in the program’s early years.[37]

Unfortunately, we are unable to determine how much the positive effect is due to student learning gains as opposed to changes in student composition, as Ohio’s district value-added estimates are unavailable for our baseline years and we were unable to obtain student-level data from ODE in time for this report. It is also important to emphasize that, despite the positive achievement effects, districts exposed to EdChoice remained exceptionally low achieving. Thus, these results do not suggest that EdChoice is a particularly effective intervention for improving the performance of traditional public schools.

Income-based EdChoice

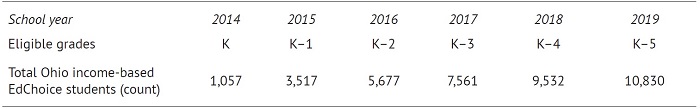

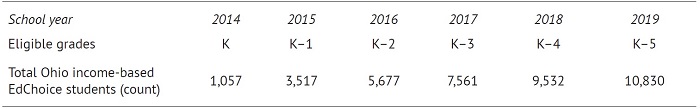

The Ohio General Assembly expanded EdChoice in 2013 when they enacted the income-based program. Beginning during 2013–14, scholarships became available to students whose families had incomes at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line and who were not in schools served by the performance-based EdChoice program. The income-based program phased in such that Kindergarten students were eligible in that first year, first graders were eligible in 2014–15, second graders in 2015–16, and so on. Students whose family incomes rose above the 200 percent poverty threshold (up to 400 percent) could continue in the program, but scholarship amounts were reduced depending on how far above the threshold family income increased.[38] Based on available federal data, we estimate that at least 603 of the 609 districts in our dataset had students that qualified for the program.[39]

Table 3. Districts with eligible students and income-based EdChoice participation

Note. All figures are calculated based on data available on the ODE website. The table excludes a sizable jump in program participation that occurred after 2019 because those years are not part of our analytic sample.

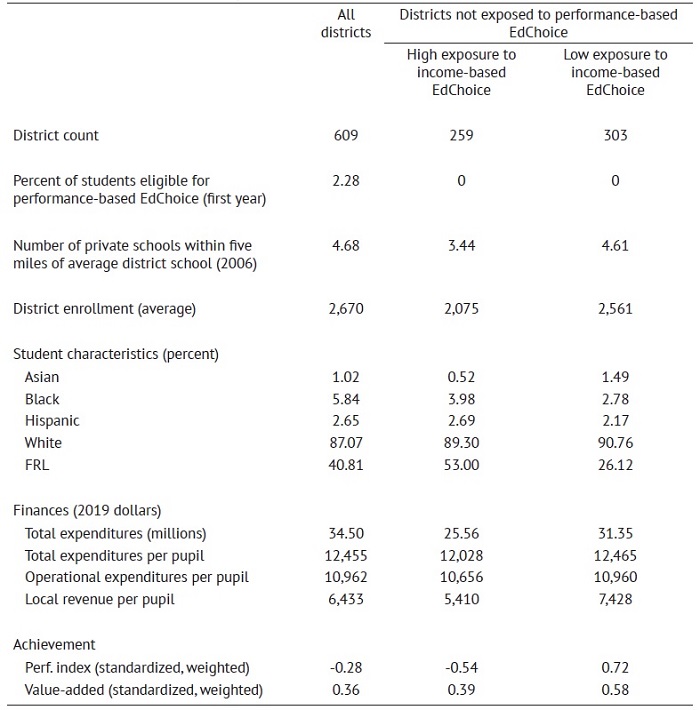

Note. All figures are calculated based on data available on the ODE website. The table excludes a sizable jump in program participation that occurred after 2019 because those years are not part of our analytic sample.Table 3 shows that very few students participated in the income-based EdChoice program during this period, given the fact that there were eligible students in over 600 districts and that over 40 percent of those in qualifying grades were eligible on the basis of family income.[40] In Table 4, below, we compare districts most and least exposed to the program by identifying the 562 districts that were not eligible for the performance-based EdChoice program (our primary analytic sample) and, among those districts, comparing those that had shares of FRL-eligible students that were above and below the statewide median in 2012. This is our best approximation of relative program eligibility across districts because, in 2012, the FRL-eligibility criterion was that a student’s household was at or below 185 percent of the poverty threshold (slightly below the voucher eligibility income threshold).

Table 4 reveals that districts with higher exposure to income-based EdChoice—those with relatively more low-income pupils in 2012—had somewhat lower enrollments (2,075 instead of 2,561), slightly lower spending per pupil (12,028 as opposed to 12,465), and substantially lower achievement levels (0.54 standard deviations below the state average, as compared to 0.72 standard deviations above the state average on the performance index). However, annual student learning gains, racial composition, and private school counts were very similar in both groups of districts. In other words, districts with more students eligible for income-based EdChoice were comparable to those with fewer eligible students when it came to district educational effectiveness, racial composition, and the extent to which the program was likely to impose competitive pressure.

Table 4. Comparing districts with high vs. low exposure to income-based EdChoice

Note. The data are from the websites of the National Center for Education Statistics, the Urban Institute, and the Ohio Department of Education. All statistics are from the 2012 school year—the year just prior to the enactment of the income-based EdChoice program. Financial variables were inflated to 2019 dollars using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Personal Consumption Expenditures Price index. The sample is limited to the 609 districts for which we have complete data and omits the Cleveland Metropolitan School District.

Note. The data are from the websites of the National Center for Education Statistics, the Urban Institute, and the Ohio Department of Education. All statistics are from the 2012 school year—the year just prior to the enactment of the income-based EdChoice program. Financial variables were inflated to 2019 dollars using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Personal Consumption Expenditures Price index. The sample is limited to the 609 districts for which we have complete data and omits the Cleveland Metropolitan School District.

Analytic strategy

Our empirical strategy parallels the strategy for the performance-based EdChoice program. It first involves determining districts’ exposure to the policy by calculating the percent of district students who qualified for the scholarship just prior to the program’s start. Doing so is more complicated in the case of the income-based program, however. First, students eligible for the performance-based EdChoice scholarship (those in low-performing schools) were not eligible for the income-based program. To address this, we estimated models that exclude the forty-seven districts exposed to performance-based EdChoice between 2007 and 2019.[41] A second challenge is that we have no data source that identifies the proportion of a district’s enrollment that was eligible for an income-based voucher. As we note above, we use as a proxy the percent of district students who qualified for FRL in 2012, which was based on whether a household was at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty threshold.[42] Thus, FRL counts from the 2012 school year should be a close approximation of the count of students near or below 200 percent of the poverty line. For our analytic sample of 562 districts, our estimate of the percent of district students eligible for income-based EdChoice (our measure of program exposure) ranges from 0 to 98 percent.

We again emphasize that the measure of program exposure is based on district features prior to the program’s start. As we explain in our discussion of the performance-based EdChoice analysis, the purpose of using a preprogram measure of exposure is to capture the full breadth of the program’s impact. It is also important to note that although the income-based EdChoice program was phased in and a district’s true exposure was limited to students in eligible grades (e.g., only low-income Kindergarteners in 2013–14), the percent of FRL-eligible students in 2012 should still roughly capture the relative exposure of school districts to the income-based EdChoice program for every subsequent year. Thus, our empirical strategy is to compare changes in outcomes—between 2012–13 and 2018–19—between districts with different levels of exposure as measured by preprogram FRL eligibility.

Unfortunately, unlike our analysis of the performance-based EdChoice program, this design does not yield plausibly causal estimates of the program’s impact. In particular, as we show in the appendixes, districts with higher (as opposed to lower) FRL rates in 2012 were experiencing relative declines in enrollments, racial isolation of minority students, and total expenditures, as well as relative increases in student achievement, in the school years leading up to 2012–13 (see Figure B1 in Appendix B). Thus, unlike the performance-based EdChoice analysis, it seems unreasonable to claim that trends in outcomes between 2013–14 and 2018–19 would have been similar for districts with high and low exposure had the program not been in place. Other attempts to get at a credibly causal design—such as comparing observationally similar districts with higher and lower densities of private schools prior to the program—similarly failed basic validity checks.[43] Thus, although we can characterize the results below as capturing differences in trends between districts that had more as opposed to fewer eligible students, we cannot characterize these relative differences as resulting from the income-based EdChoice program.

Finally, let us note a couple of other limitations of this analysis. First, the exceedingly low participation rate for the average Ohio district (as implied by Table 3 above) makes it unlikely that we would have the statistical power to detect program effects even with a valid design.[44] Second, the time horizon is limited. The program was still being phased in as of 2018–19, when students in grades K–5 were eligible. That means the program’s impact on districts could not approach a relatively steady state by 2018–19, as the performance-based EdChoice program had. That the program was still phasing in also precludes our pooling outcomes for the 2016–17 through 2017–19 school years to enhance statistical power, as we did for the analysis of performance-based EdChoice. Thus, even if the analytic strategy we employ were to generate plausibly causal estimates of income-based EdChoice’s impact, it seems unlikely that those effects would be sufficiently large to be statistically distinguishable from null effects.

To reiterate, our analysis focuses on comparing changes in outcomes between the 2012–13 and 2018–19 school years, depending on a district’s approximate exposure to income-based EdChoice—which, as we note above, ranges from roughly 0 to 98 percent of district students being eligible for the program. Consequently, the raw estimates from our statistical models (which appear in Appendix B) indicate, roughly, how much one additional percentage-point increase in exposure to income-based EdChoice corresponded to outcomes in 2018–19. Once again, for ease of interpretation, three of the four figures below report estimates as percent changes (compared to 2012–13) for the average district.

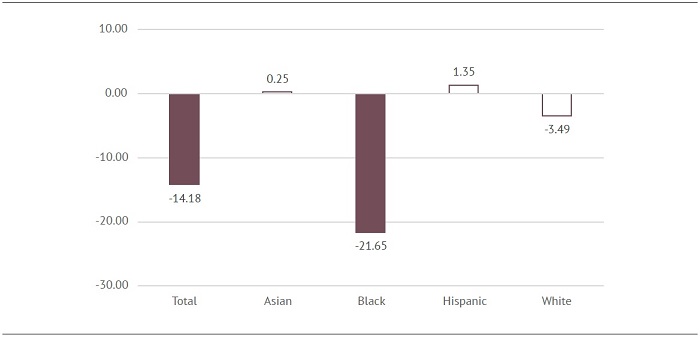

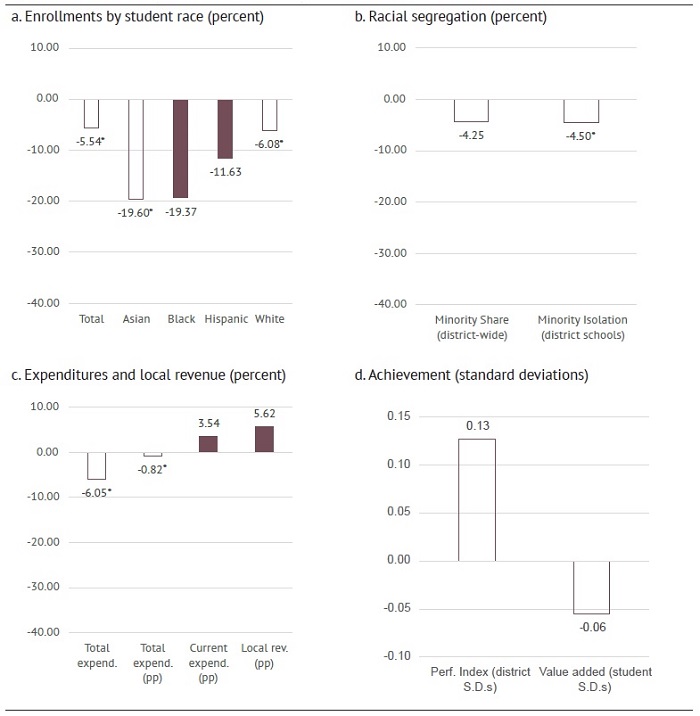

Relative changes in outcomes associated with exposure to income-based EdChoice

Figure 5 (below) reports relative changes in outcomes for districts with average levels of exposure to income-based EdChoice. The outcome measures are the same as those in the analysis of performance-based EdChoice except we now also have Ohio’s district “value-added” measure, which captures annual gains in student achievement on mathematics and English language arts exams. Additionally, because districts with higher (as opposed to lower) exposure to the program had significantly different trends in the years leading up to the program, the figures capture the sensitivity of estimates when we control for differences in prior trends.[45] To reflect such sensitivity in our estimates, Figure 5 reports solid bars if an estimate is statistically significant and is not sensitive to controlling for prior trends.[46]

The results in Figure 5a reveal that districts with average exposure to the income-based EdChoice program experienced, on average, relative declines in enrollment of 5.54 percent (since 2012–13) and that those declines affected all racial and ethnic subgroups. However, when one accounts for differences in district-specific preprogram trends, one sees relative increases in enrollments overall and among Asian American and White students. Consequently, the only two estimates that are represented with solid bars are enrollment declines among Black and Hispanic students, whose relative enrollment declines are not merely a continuation of trends from the years leading up to establishing the program in 2013. The relative decline of 4.25 percent in the share of minority students (reported in Figure 5b), although statistically insignificant, seems to confirm this result. Indeed, as we show in the appendixes, supplementary analyses suggest that increased exposure to income-based EdChoice is associated with a decline in the share of minority students in a district—that is, a decline in the share of district students who are Black, Hispanic, or American Indian or Alaskan Native.

The school-level segregation estimates are perhaps least informative of all. The main estimate of minority isolation indicates a relative decline in segregation, but, as we show in the appendixes, accounting for district-specific preprogram trends suggests a relative increase in the isolation of minority students across district schools. Consequently, to communicate the weakness in this finding, the estimate in Figure 5b is denoted with a star and the bar is empty. This instability and statistical insignificance, which characterize results for all segregation measures (e.g., see results in Appendix B) are unsurprising. The share of district students who are Black, Hispanic, or Native American—as well as the isolation of these students in district schools—are very low in these 562 districts. For example, whereas the average student in a district exposed to performance-based EdChoice was in a district where 49 percent of students were racial or ethnic minorities, that figure was only 10 percent in the 562 districts in this analysis of income-based EdChoice. Thus, there is very little variation, and segregation measures might be problematic.[47]

The most robust results are those related to district expenditures and revenues (Figure 5c). Statistical models consistently indicate a positive association between our measure of exposure to income-based EdChoice and current expenditures per pupil (a relative increase of 3.54 percent) and local revenue per pupil (a relative increase of 5.62 percent).[48] If there is one takeaway from the income-based analysis on which we might put some weight, it is that there is no credible evidence of revenue or expenditure declines. All credible evidence points in the opposite direction.

Finally, estimates of district achievement levels and annual “value-added” achievement gains (Figure 5d) are statistically insignificant across all statistical models. Unfortunately, these estimates are too imprecise to rule out achievement effects that researchers would consider to be substantively meaningful. As we note above, the limited take-up of the income-based program and our inability to obtain student-level data prevents us from conducting an analysis sufficiently precise to reveal the income-based EdChoice program’s impact on student achievement.

Figure 5. Relative changes in enrollments, segregation, finances, and achievement

Note. The figure presents the estimated change in district enrollments, racial segregation, expenditures and revenue, and achievement associated with average exposure to income-based EdChoice between 2013–14 and 2018–19. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact, and bars below zero indicate a negative impact. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test AND that coefficient estimates have the same sign in models that control for district-specific trends. Statistically significant estimates for which the district-trend model had an opposite sign are noted with a star.

Note. The figure presents the estimated change in district enrollments, racial segregation, expenditures and revenue, and achievement associated with average exposure to income-based EdChoice between 2013–14 and 2018–19. Bars above zero indicate a positive impact, and bars below zero indicate a negative impact. Solid bars indicate that the estimates are statistically significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed test AND that coefficient estimates have the same sign in models that control for district-specific trends. Statistically significant estimates for which the district-trend model had an opposite sign are noted with a star.

Conclusion

The analysis indicates that the performance-based EdChoice program led to lower levels of segregation among minority students, no change (and perhaps an increase) in district expenditures per pupil, no change in districts’ ability to generate local revenue (leading to an increase in local revenue per pupil), and higher academic achievement among the remaining district students. The analysis of the income-based EdChoice expansion program was mostly inconclusive. What one can say, however, is that an analysis of publicly available data yields no credible evidence that the income-based EdChoice expansion had a negative impact on district revenues, segregation, or achievement. In future work, we hope to use student-level data to get more credible impact estimates of the income-based program, as well as estimates of the performance-based program’s long-term impact on student learning.

Between 2006 and 2019, EdChoice-eligible schools did indeed experience increases in racial and ethnic segregation, as well as declines in achievement (see Figure D1 in Appendix D). These trends had begun well before 2006, however, and this study provides compelling evidence that they should not be attributed to private school vouchers. In fact, the analysis indicates that district segregation and achievement would have been worse in the absence of the performance-based EdChoice program.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Figlio, Brian Kisida, and Vlad Kogan for helpful reviews of an earlier draft. We also thank Joshua Sadvari at The Ohio State University library for helping us geolocate schools. Last but not least, we thank the Thomas B. Fordham Institute—particularly Aaron Churchill, Chad Aldis, Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Michael J. Petrilli—for making this project possible, for offering their expertise on Ohio education policies, and for helping us make this report intelligible.

– Stéphane Lavertu and John J. Gregg

We offer our deepest thanks to Stéphane Lavertu and John J. Gregg for their detailed, rigorous analysis of Ohio’s EdChoice voucher programs. On the Fordham team, we wish to thank Michael J. Petrilli and Chester E. Finn, Jr. for their thoughtful feedback during the drafting process; we also thank our Columbus colleague Jeff Murray for assisting with report dissemination. We express our gratitude to Dr. David Figlio of the University of Rochester and Dr. Brian Kisida of the University of Missouri for their feedback on the report. Last, special thanks to Pamela Tatz who copyedited the manuscript and Andy Kittles who created the design.

– Aaron Churchill and Chad L. Aldis, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Endnotes

[1] Joe Biden, “Remarks by President Biden At Signing of An Executive Order Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” Speeches and Remarks, Briefing Room, The White House, July 7, 2021.

[2] George W. Bush, “President Bush Discusses Financial Markets and World Economy,” Office of the Press Secretary, The White House George W. Bush Archives, November 13, 2008.

[3] See, for example, polling from EdChoice (an organization not related to Ohio’s voucher program) and the American Federation for Children.

[4] Caroline M. Hoxby, “School Choice and School Productivity. Could school choice be a tide that lifts all boats?” in The Economics of School Choice, ed. Caroline M. Hoxby (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 287–341; David N. Figlio, Cassandra M. D. Hart, and Krzysztof Karbownik, “Effects of Scaling Up Private School Choice Programs on Public School Students” (CESifo Working Paper No. 9056, Munich, 2021; and Anna J. Egalite, “The Competitive Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Public School Performance” (Program on Education Policy and Governance Working Paper 14-05, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA, 2014).

[5] David Griffith, Rising Tide: Charter School Market Share and Student Achievement (Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2019).

[6] David Figlio and Krzysztof Karbownik, Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, Competition, and Performance Effects (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2016).

[7] Information about the case—Columbus City School District, et. al. vs. State of Ohio—is available on the Franklin County court’s website.

[8] Eligibility for performance-based EdChoice hinges on the academic performance of the district school to which a student is assigned. In 2021–22, 36,824 students participated in this program.

[9] In 2021–22, 20,783 students participated in this program.

[10] Figlio and Karbownik, Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program.

[11] EdChoice programs experienced large increases in participation rates between 2019 and 2021, though some of this is attributable to the expansion of eligibility in 2019. Evidence of parents’ exit from public schools—particularly when districts offered only remote instruction—is available here: Tareena Musaddiq, Kevin Stange, Andrew Bacher-Hicks, and Joshua Goodman, “The Pandemic’s effect on demand for public schools, homeschooling, and private schools,” Journal of Public Economics 212, no. 104710 (August 2022). Evidence that private schools were more likely to stay open during the pandemic is available here: Michael B. Henderson, Paul E. Peterson, and Martin R. West, “Pandemic Parent Survey Finds Perverse Pattern: Students Are More Likely to Be Attending School in Person Where Covid Is Spreading More Rapidly,” Education Next 21, no. 2 (Spring 2021).

[12] The remainder participate in the Jon Peterson Special Needs scholarship program, Autism Scholarship Program, and Cleveland Scholarship Program.

[13] According to Education Next’s 2022 public opinion poll, around 50 percent of both Democrats and Republicans support universal school vouchers, whereas about 40 percent oppose them. Majorities of Black respondents (72 percent) and Hispanic respondents (58 percent) support them, whereas 44 percent of White respondents support them. See David M. Houston, Paul E. Peterson, and Martin R. West, “Partisan Rifts Widen, Perceptions of School Quality Decline: Results of the 2022 Education Next Survey of Public Opinion,” Education Next 22, no. 4 (Fall 2022).

[14] Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Private School Vouchers and Student Achievement: An Evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 2 (May 1998): 553–602; Joshua M. Cowen et al., “School Vouchers and Student Attainment: Evidence from a State-Mandated Study of Milwaukee’s Parental Choice Program,” Policy Studies Journal 41, no. 1 (2013): 147–68; Patrick J. Wolf et al., “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, D.C.,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32, no. 2 (2013).

[15] See Atila Abdulkadiroğlu, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “Free to Choose: Can School Choice Reduce Student Achievement?” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, no. 1 (January 2018): 175–206; R. Joseph Waddington and Mark Berends, “Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement Effects for Students in Upper Elementary and Middle School,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37, no. 4 (2018): 783–808; Figlio and Karbownik, Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program; Mark Dynarski et al., Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts After Two Years (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, U.S. Department of Education, NCEE 2018-4010, May 2018).

[16] These studies are of uneven quality, but the results are consistent. For example, the relatively rigorous Milwaukee and Washington, D.C., evaluations cited above both found that participating families reported increased satisfaction and perceived improvements in school safety.