Contrary to much public rhetoric, the evidence for expanding charter schools in urban areas is stronger than ever. To be sure, the research is less positive for charters operating outside of the nation’s urban centers. And multiple studies suggest that internet-based schools and charters that serve mostly middle-class students, perform worse than their district counterparts, at least on traditional test-score-based measures. But like the technologies behind renewable energy (which work poorly in places where the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine) charters needn’t work everywhere to be of service to society. And these days, society needs all the help it can get, which is why the evidence on urban charter schools is worth revisiting and absorbing.

The evidence on urban charter schools

In general, the most rigorous studies of charter schools rely on data from the randomized admissions lotteries that are conducted when individual schools are oversubscribed, which ensure that research resembles a natural experiment.

With few exceptions, these lottery-based studies have found that attending oversubscribed charter schools is associated with higher achievement in reading and math—especially in large, human-capital-rich cities such as Boston, Chicago, and New York City. For example, a 2011 study of the Promise Academy charter schools in the Harlem Children’s Zone found the effects of attendance in middle school were “enough to close the Black-White achievement gap in mathematics,” while the effects in elementary school were “large enough to close the racial achievement gap in both mathematics and [English language arts].”

Obviously, if all charter schools were so effective, there would be little to debate. But unfortunately, those that are popular enough to make use of admissions lotteries are likely atypical. Consequently, although lottery-based studies may tell us something important about the schools in question—and, perhaps, about the potential gains associated with the policies that allow them to do their work—this research tells us little about the overall performance of urban charter schools.

In an effort to overcome this limitation, many recent studies have used a statistical technique known as “matching” to compare the academic trajectories of students in charter schools to students in traditional public schools with similar characteristics and levels of academic achievement. For example a 2012 study that used matching found that students in Milwaukee charter schools made more progress in English language arts (ELA) and math than otherwise similar students in traditional public schools, as did a more recent study of students in Los Angeles charters.

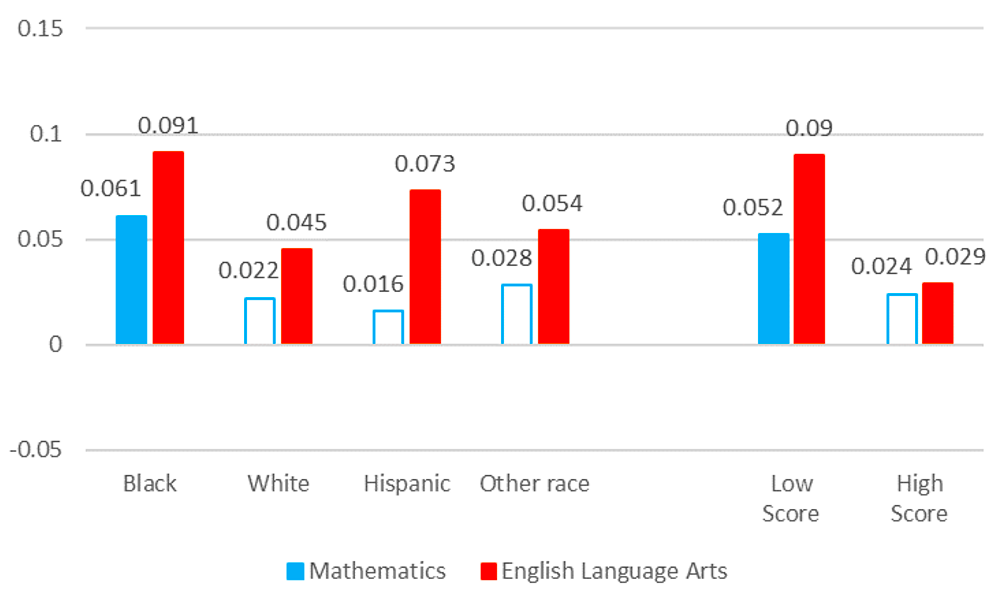

Although there are many approaches to matching, perhaps the best known in education circles is the virtual control record (VCR) method developed by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University. CREDO has used the VCR method in recent years to generate an extensive collection of national, state-, and city-specific estimates of the “charter effect.” For example, in a 2015 analysis of charter performance in forty-one urban locations, CREDO estimated that students who attended a charter school in these cities gained an average of twenty-eight days of learning in ELA and forty days of learning in math per year. (For the purposes of this discussion, 180 days of learning can be thought of as the progress the average American student makes in the average school year.) Students who enrolled in an urban charter school for at least four years gained a total of seventy-two days of learning in ELA and 108 days—over half a year’s worth of learning—in math.

Notably, these gains were concentrated among low-income Black and Latino students. For example, Black students in poverty gained forty-four days of learning in ELA and fifty-nine days of learning in math per year. Similarly, Latino students in poverty gained twenty-five days of learning in ELA and forty-eight days of additional learning in math. And students with English-language-learner status gained seventy-nine days of learning in ELA and seventy-two days of learning in math.

Nationally, ELA and math achievement gaps between White students and Black and Latino students are roughly two grade levels. So while most charter schools aren’t erasing racial achievement gaps, the average urban charter is putting a sizable dent in them.

Charters and traditional public schools

Since the goal of public education is to serve all students effectively, one key question is whether the success of students in charter schools comes at the expense of their peers in traditional public schools. Yet contrary to the assumptions of many charter-school opponents, there is little evidence that this is the case.

In fact, most of the “spillover” effects that charter schools have on the traditional public schools in their vicinity appear positive—or at worst, neutral. To wit, a recent review of the literature on this question identified nine studies that found positive effects, three that found negative effects, two that found mixed effects, and ten that found no effects whatsoever. As that summary suggests, evidence that charter competition has salutary effects on district-run schools has now been detected in a wide variety of contexts, from the dense urban cores of Milwaukee and New York City to the sprawling suburbs of Florida, North Carolina, and Texas.

Logically, if urban charter schools have a positive effect on their own students’ achievement and a neutral or positive effect on other students’ achievement, it follows that their overall effect on student achievement must be positive. So to test that hypothesis, a recent Fordham report examined the relationship between the “market share” of local charters—that is, the percentage of publicly enrolled students in a geographic school district who attend a charter school—and the average reading and math achievement of all students (including those in traditional public schools). Overall, that analysis suggested that an increase in the former was associated with an increase in the latter, especially in Black and Latino communities and in the largest urban areas. In other words, at least when it comes to charter schools in America’s biggest cities, a rising tide really does lift all boats.

Beyond academic achievement

While most parents expect their children to leave school with a mastery of critical academic skills and knowledge, the ultimate success of an education lies in the degree to which it empowers students to thrive in adulthood. Consequently, to gauge the true efficacy of charter schools, researchers need to get beyond test scores—if and when they can.

Fortunately, a growing number of studies allow us to examine the relationship between enrollment in charter schools and long-term, real-world outcomes. For example, one evaluation of a high-performing “no excuses” charter school in Chicago found that, compared to their peers, lottery winners were “10 percentage points more likely to attend college and 9.5 percentage points more likely to enroll for at least four semesters.” Similarly, in a follow-up study of the Harlem Children’s Zone’s Promise Academy, researchers found that the same students who had previously experienced large test-score gains were also “14.1 percentage points more likely to enroll in college.” Furthermore, admitted female students were “12.1 percentage points less likely to be pregnant in their teens,” while male students were “4.3 percentage points less likely to be incarcerated.”

Other lottery-based studies encompass multiple schools. For example, one study found that attending an oversubscribed Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) middle school between 2008 and 2011 had a positive effect on post-secondary enrollment. Similarly, a 2016 study found that charters increased pass rates on Massachusetts’ high-school exit exam, leading to “a substantial shift from two- to four-year institutions.” Finally, a recent study of the Democracy Prep charter network found that it boosted students’ odds of voting in the 2016 election by six percentage points.

Like the lottery-based studies of charter schools’ impact on achievement, this research doesn’t necessarily generalize to all charter schools. However, at least two studies have used matching techniques to estimate the long-term effects of charter attendance for entire cities or states. The first, a 2011 study of charter schools in Florida and Chicago, found that “among students who attended a charter middle school, those who went on to attend a charter high school were 7–15 percentage points more likely to earn a standard diploma than students who transitioned to a traditional public high school,” as well as “8–10 percentage points more likely to attend college.” The second, a more recent study of charter schools in North Carolina, found that students who attended a charter high school were “less likely to be chronically absent, suspended, be convicted of a crime as an adult, and more likely to register and participate in elections.”

In short, although the literature on charter schools’ long-term effects is still developing, the early evidence—like the two studies mentioned above—is extremely encouraging as well as highly consistent with the evidence on charter schools’ short-term effects on academic achievement.

Racial integration

In the absence of compelling alternatives, the claim that charters exacerbate segregation has become opponents’ most potent line of attack. Yet the evidence for this claim is mixed.

To wit, a recent literature review identified ten studies of charter schools and racial integration, including two that found they increased integration, five that found no significant effect, and three that found that they decreased integration (i.e., increased or at least preserved segregation). Meanwhile, in the most comprehensive analysis to date, researchers at the Urban Institute found that higher charter market share was associated with a small increase in racial segregation within the average school district. However, that same study also found that charter schools reduced segregation between school districts. Consequently, when the analysts looked at segregation across entire metro areas, they found no significant effects.

For some charter skeptics, even the faintest whiff of “re-segregation” is the end of the conversation. But for several reasons, it really shouldn’t be.

First, American schools are already highly segregated, so it’s not like charters are derailing an otherwise successful program of racial integration.

Second, much of the most segregation that is most visible to students takes place within outwardly diverse schools, where pre-existing achievement gaps can and do lead to highly segregated classrooms insofar as math and other subjects are tracked.

Third, some research suggests that, because it “decouples” housing and education markets, school choice makes it more likely that White parents will move into “racially segregated urban communities.” In other words, even if charters lead to slightly less diverse schools, their arrival may mean that neighborhoods become more diverse.

Finally, it is simply a fact that many “racially isolated” charters achieve exceptional results for the students they serve. And of course, there is a huge difference between forced segregation and allowing families to opt out of a system designed by and for the White majority: Students and parents at an all-Black or all-Hispanic charter school that defies society’s expectations of failure are hardly modern-day Bull Connors.

Critics of the research

As should be obvious, much of the pro-charter argument depends on the validity of the methodologies upon which researchers have relied (and of CREDO’s methodology in particular). So given how much is at stake, it’s worth taking a moment to understand the various criticisms of CREDO’s approach, most of which can be summarized in two points.

First, critics claim that CREDO’s estimates could be biased by unobserved differences between students in charter schools and students in traditional public schools. In other words, it’s possible that the students in charter schools make more progress than “otherwise similar” students (i.e., students with similar demographic characteristics and prior achievement) in traditional public schools because of factors that are hard to measure, like unusually involved parents.

Second, critics argue that even if CREDO’s estimates are unbiased, they might not generalize to other locations or higher levels of charter market share. For example, if the 25 percent of Boston’s Black students who are enrolled in a charter school are above average, easier to teach, or otherwise different from the rest of the city’s Black student population, the same schools that are seemingly serving these students so well might struggle to replicate their results with the other three-quarters of that population. And of course, insofar as the extraordinary success of Boston’s charter schools depends on conditions that are not replicable—such as the city’s unusually deep reservoir of human capital—it may be difficult to reproduce this success in other locations.

For each of these criticisms, there is a compelling counterargument. For example, when the federal Institute of Education Sciences (IES) evaluated non-experimental methods for studying charter schools, it found that matching studies generated “impact estimates that are not significantly different from the experimental estimates.” Other attempts to assess the validity of matching approaches have reached similar conclusions. And in general, it’s difficult to overlook the similarities between CREDO’s estimates and those generated by other quasi-experimental or experimental studies. Like the CREDO studies, for example, those studies find large positive effects for disadvantaged students and students of color, a stark gap between the performance of urban and non-urban charter schools, and strikingly positive results in major cities such as Boston and New York, but mixed or negative results in states like Arkansas, and Ohio (though not when online schools are excluded) all of which suggests that CREDO’s estimates should be taken seriously.

As for the second criticism, although our knowledge of the opportunities and challenges associated with an exclusively charter-based system is thus far limited to the experience of New Orleans (which made the switch almost overnight following Hurricane Katrina), we now have quite a bit of experience with “charter-heavy” systems, where charter market share is somewhere between 15 percent and 45 percent. And in general, the evidence collected in such environments suggests that the returns associated with higher charter market share do not necessarily diminish as charter market share increases. For example, one rigorous analysis found that the “average effectiveness of Boston’s charter middle school sector increased...despite a doubling of charter market share.” And CREDO’s 2015 estimates for cities like Detroit and Washington, D.C., were highly positive, despite the fact that charter schools enroll more than a third of the students in these cities. Finally, the evidence suggests that New Orleans’s leap of faith led to substantial gains for students—although it’s not clear how much smaller those gains would have been if the city had stopped at 50 percent or 75 percent charter market share instead of going all the way.

Obviously, even if one takes CREDO’s estimates at face value and accepts that there is room for growth in most places, it’s still the case that charter performance varies by location. But what this criticism often overlooks is that charter policy also varies by location. So at best, this line of reasoning is a double-edged sword. After all, nothing but politics prevents states and localities from adopting smarter education policies.

Improvements over time

Collectively, the research discussed makes a compelling case for expanding charter schools in urban areas. Yet that case would be incomplete without a final, critical, and frequently overlooked point: Charter schools (and urban charters in particular) have improved since the movement’s inception—even as their numbers have increased—and will probably keep improving in the coming years.

The first half of this claim is difficult to contest. For instance, after breaking down previously collected achievement data according to school year, CREDO estimated that students in urban charter schools gained twenty-four days of learning in reading and twenty-nine days of learning in math in 2008–09. Yet by 2011–12, it estimated that these figures had increased to forty-one days for reading and fifty-eight days for math. Similarly, meta-analyses of the lottery-based and quasi-experimental charter-school literature suggest a gradual improvement in overall performance. For example, a 2008 review of seventeen lottery-based and value-added studies found “compelling evidence that charter schools underperform traditional public schools in some locations, grades, and subjects, and outperform them in other locations, grades, and subjects.” Yet in 2018, the same authors concluded that charter schools had positive effects in the elementary and middle grades, with no statistically significant effects in high school.

While the reasons for this improvement are complex, it stands to reason that it is at least partly attributable to the inevitable learning process that occurs whenever a new idea is introduced. After all, thanks to nearly two decades of research, we now know quite a bit about what sorts of charter schools work best, for whom, and under what circumstances. For example, another landmark CREDO study (as well as other research) suggests that non-profit “charter management organizations” (CMOs) are, on average, higher performing than for-profit networks or independent “mom-and-pop” charter schools. And numerous studies have found that “no excuses” schools have a particularly positive effect on Black students’ achievement. Finally, as noted previously, we know that charter schools in urban areas outperform those in rural and suburban districts, especially when it comes to serving Black and Latino students.

Though it’s unlikely to persuade the critics, one obvious implication of all this research is that we should allow high-performing CMOs like KIPP, Success Academy, and IDEA to expand their footprints in major urban areas. And in fact, that’s more or less what’s been happening in places where charter schools in general have been allowed to grow: Since 2015, according to the National Association for Charter School Authorizers, the share of newly created charter schools run by for-profit entities has fallen from 20 percent to around 10 percent, while the share of new schools run by CMOs has increased to 40 percent.

Once one starts looking for them, signs that states and localities are learning from one another’s experiences are everywhere. For example, at least half a dozen cities have now adopted common applications that make it easier for parents to choose from and apply to multiple schools. Or take Texas, which historically has had a relatively low-performing charter sector. In 2013, the Lone Star State boosted funding for its charter schools while also moving to close its lowest performers. Following the law’s passage, CREDO’s estimate of Texas charter schools’ effect on math learning went from negative seventeen days per year in 2013 to positive seventeen days per year in 2015, with even larger gains for poor students and the state’s ever-expanding Latino population.

This improvement is too recent to be reflected in CREDO’s national estimates, as are the widely recognized improvements in several other states’ charter sectors. But the more important point is that, even after twenty-five years of “learning” on the part of both states and localities, charter-school policy in most places is far from optimal. To wit, a 2018 study found that, once the cost of facilities and other unavoidable expenses was taken into account, charter schools received 27 percent—or about $6,000—less per pupil than traditional public schools. And in more than a dozen major urban districts—including Atlanta, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Washington, D.C.—it has been estimated that charter schools receive anywhere from 25 percent to 50 percent less revenue per pupil than traditional public schools. In other words, urban charter schools are achieving their remarkable results despite spending far less money per pupil than their district counterparts.

Just imagine what they could accomplish if that weren’t the case.

Renewing the promise of charter schools

In recent decades, education reformers have experimented with numerous approaches to boosting the achievement of disadvantaged children— from reducing class sizes, to insisting that teachers receive “National Board Certification”, to investing heavily in failing schools. Yet ultimately, most of these ideas were abandoned because they were politically untenable or, in hindsight, unscalable or ill-conceived. In contrast, the case for charter schools has only strengthened over time—and the experiences of places like New Orleans, Newark, and D.C. suggest we have only begun to realize their potential.

Precisely why urban charter schools work so well for students of color is difficult to say. In theory, freedom from district bureaucracies and teacher-union contracts should allow them to make better hiring decisions, appropriately reward strong performance, and part ways with ineffective teachers when necessary. But it’s also possible that more intense competition between schools encourages them to make better use of their resources, or that the periodic closure of low-performing charter schools leads to a gradual improvement in quality. Or perhaps allowing more school choice improves the “match” between students and schools in ways that disproportionately benefit at-risk students. Since research supports each of these theories, the best possible answer to the question of causal mechanisms may simply be “all of the above.”

Despite what many may have heard, the growth of charter schools is not out of control. To the contrary, where growth has been permitted, it is completely under the control of disadvantaged populations that can now exercise their right to pursue a better education. And despite the overheated rhetoric that dominates public conversation, the truth is that charter schools enroll a modest percentage of students in most major cities. For example, in New York City, they enroll just one in five Black students and one in ten Latino students. Yet at the start of the 2019-20 school year, nearly 50,000 families in the Big Apple were denied a place in a charter school.

Nationally, roughly one-quarter of Black students and perhaps one in six Latino students in urban districts attend a charter school. So how much progress could we make by expanding charter market share for these groups?

Although any concrete estimate is subject to criticism, our back-of-the-envelope arithmetic suggests that moving from 25 percent to 50 percent charter market share in urban areas could cut the achievement gap in half for at least 2.5 million Black and Latino students in the coming decade. And of course, with more equitable funding, improved oversight, and an expanded role for truly high-performing networks, the dividends might be even larger.

So what are we waiting for?

Editor’s note: This was first published by National Affairs.