With Ohio’s safe harbor provisions now in the rearview mirror, formal consequences for poor school ratings have reemerged. Among them is the automatic closure law, first enacted in 2006, which requires low-performing charter schools to permanently close. Recently, the Ohio Department of Education released data revealing that fifty-two of Ohio’s 311 charter schools are at-risk of closure under this statute (including one sponsored by our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation). Taken together, the schools on this “watch list” enrolled 15,557 students last year, about the size of the Dayton Public School District. Charters are in jeopardy of closure when assigned F’s on specific measures—e.g., performance index and value added—based on their most recent data; schools must close when they receive two years of low ratings within a three-year window.

There are rumors about efforts to roll back the automatic closure statute. That’s not surprising given the severity of the penalty and the sharp rise in the number of charters in jeopardy of closure. As my former colleague Jamie Davies O’Leary has reported, only four schools sat on the watch list in the year prior to safe harbor. While not every school on the current watch list will close—some will post higher ratings this year—even twenty to thirty closures would be far higher than in the pre-safe-harbor era. From 2008–09 to 2013–14, a total of twenty-four charters—an average of four per year—closed under the law.

What to do? Two key questions should be raised before arriving at a conclusion. First, why are there so many more charters on this year’s watch list? There are two principal explanations, neither of which indicate deteriorating charter quality but are instead related to shifts in state accountability policies.

1) Dropout recovery charters were not previously subject to automatic closure but now are. In conjunction with the creation of an alternative rating system, lawmakers in 2012 removed the exemption from the automatic closure law previously given to dropout-recovery charter schools.[1] Eighteen dropout-recovery schools landed on this year’s closure list, and with tougher dropout-recovery standards on the horizon, more may fall prey to automatic closure in the coming years.

2) Performance index ratings, one of the key closure criteria, are lower today due to higher proficiency standards. Generally, most elementary and middle school charters are subject to closure when they receive two years of F’s on the performance index and the value-added-progress component within a three-year period.[2] However, these criteria were created prior to accountability transitions that began in 2014–15. While policymakers were right to strengthen state exams and proficiency standards, doing so depressed proficiency-based ratings such as the performance index. In 2013–14, prior to the transition, the statewide performance index score was 96.8. In 2017–18, it had sunk to 84.2.

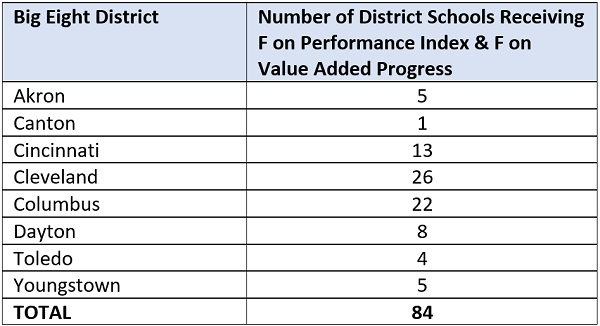

There has also been a huge jump in the number of F’s in the Big Eight urban areas where most charters are located. In 2013–14, just forty schools in these cities (both district and charter) received F’s on the performance index; that number now stands at 211. Though not a perfect estimation, table 1 illustrates that, akin to their charter counterparts, dozens of Big Eight district schools would likely be on the chopping block under today’s tougher standards if they faced an automatic closure penalty—but no such law exists for districts.

Table 1: Big 8 district schools receiving F’s on performance index and value-added progress (2017–18)

Source: Ohio Department of Education, Download Data. Note: This data is not an exact determination of district schools that would be at-risk of closure under the charter law. It includes some high schools that would be evaluated under slightly different criteria (e.g., F overall and F value-added progress); moreover, the value-added measure itself differs for the purposes of determining charter closures (it relies on a one-year value-added score, instead of a three-year average score, which is used to generate report card ratings, and it excludes some highly mobile students).

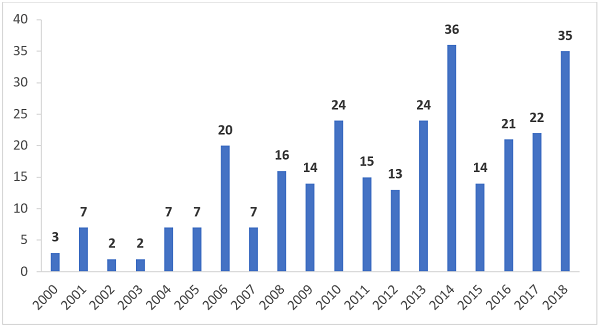

The second question is whether automatic closure remains a necessary policy tool, given the major charter policy improvements the legislature put in place in recent years. Specifically, the implementation of a sponsor evaluation system has put pressure on sponsors—the entities charged with school oversight—to close low-performing schools. Back in 2006, when the closure law initially passed, no evaluation system existed. There was little pressure on sponsors to consider performance factors in regard to closure, and they had a financial incentive to keep as many schools open as possible. That changed in 2013 when the legislature created an evaluation system designed to incentivize quality sponsorship practices, including closing schools that consistently miss performance targets. Two years later, this system was further sharpened with the passage of House Bill 2 in which lawmakers introduced stiffer penalties for ineffective and poor sponsor ratings. Overall, this accountability lever has led to the closing of numerous low-performing charters—even during the recent period of safe harbor, as figure 1 below indicates.

Figure 1: Charter closures by year, FYs 2000–18

Sources: Data for FY00–17 are based on Jamie Davies O’Leary’s calculations. For FY18, I used ODE’s closure list. Note: Six of the FY18 closures are reported as mergers with another school.

***

We’re entering a time period where the state’s more stringent accountability policies have put more charters in jeopardy of automatic closure than ever before—likely more than originally intended under the closure law. And due to recent reforms, charter sponsors themselves are now more likely to shutter low-performing schools. Based on the latter conclusion, one could make a good case for repealing the closure law. In my view, however, retaining a fail-safe that ensures students don’t wind up in chronically failing schools is prudent policy. Much is at stake for Ohio’s kids, and they can’t afford to spend years in abysmal schools, especially if superior options exist. (This should apply to districts, too!)

Yet lawmakers should revise the closure criteria so that the “death penalty” applies only in the most extreme cases. The current metrics upon which closures are determined—the overall, performance index, and value-added progress ratings—make good sense because they are key indicators of pupil achievement and growth. But closing schools based on just two years of ratings is a quick hook. In fact, the original closure law premised closure on either three or four consecutive years of poor performance, depending on grade span, with the shift to two years occurring in 2009. That may have been a sensible standard during an era of low expectations, but now that the state has tightened standards, reverting to an approach requiring three years of poor ratings would be wise. This would allow schools time to implement turnaround efforts once they’ve been put on notice, and would ensure that the law only closes schools that are true, chronic failures.

Ohio has made great strides in strengthening accountability via its sponsorship system. The resumption of Ohio’s automatic closure law is another piece of the accountability puzzle, ensuring that the lowest-performing charters either improve or permanently close. Given the significant policy shifts since the enactment of the original closure law, legislators should revisit the state’s automatic closure criteria. As in baseball, it should be three strikes and you’re out.

[1] Only charters serving a majority of special-education students and schools in their first two years of operation remain exempt from automatic closure.

[2] State law specifies a few other conditions based, for example, on schools’ overall ratings that can trigger automatic closure.