NOTE: Today the Ohio Report Card Study Committee heard testimony from a number of stakeholder groups on various aspects of the state’s school and district report cards. Fordham vice president Chad Aldis was invited to provide testimony. This is the written version his remarks.

Introduction

Thank you Chair Blessing, Chair Jones, and workgroup members for inviting me to offer testimony on Ohio’s state report card. My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

For two decades, Ohio has published annual report cards that provide families and citizens, educators and policymakers with information about school quality. Just like an annual medical checkup, these report cards are routine checks on the academic health of schools, letting us know when students are meeting learning goals, while also raising red flags when children are falling behind.

The main purpose of the state report card is straightforward: To offer an honest appraisal of school quality. For families, the report cards offer objective information as they search for schools that can help their children grow academically. For citizens, they remain an important check on whether their schools are thriving and contributing to the well-being of their community. For governing authorities, such as school boards and charter sponsors, the report card shines a light on the strengths and weaknesses of the schools they are responsible for overseeing. It can also help officials identify schools in need of extra help.

Key Principles

Yet creating a report card that meets the needs of so many stakeholders is no walk in the park. That’s why we’re here today. Before diving into the particulars, it’s important to step back and consider four key principles that we at Fordham believe are crucial to the report card design.

- Transparent: Report cards should offer user-friendly information that can be understood by all of Ohio’s families and citizens, most of whom work outside of education.

- Fair: The report card should be fair to students by encouraging schools to pay attention to the needs of all students. It should also be fair to schools and designed in a way that allows schools serving students of all backgrounds to stand out.

- Rigorous: Report card measures should challenge schools to improve student outcomes.

- Consistent: The report card should remain largely consistent from year-to-year, helping to build public confidence and enabling stakeholders to track progress.

Strengths of Ohio’s Current Report Card

With these principles in mind, it’s important to recognize the strengths of Ohio’s current framework, which has earned praise from national education groups. As you consider changes to the report card, we believe these foundational elements should remain firmly in place.

Overall rating. Akin to a GPA, Ohio’s overall rating offers a broad sense of performance by combining results from disparate report card measures. This prominent, user-friendly composite rating focuses public attention on the general academic quality of a school. In contrast, a system without a final rating risks misinterpretation. It would enable users to “cherry pick” high or low component ratings that, when considered in isolation, could misrepresent the broader performance of a district or school. We’ve already seen this occur—in 2017, one media outlet focused on the F’s received by several districts on indicators met, but skipped almost entirely over the other ratings. Failing to assign an overall grade could also lead users to “tally up” component ratings on their own in a crude effort to create an overall grade. For example, district X’s four A’s might look better than district Y’s three A’s. But such a conclusion could very well be incorrect, since it treats all components as equally important. Some measures, such as achievement and growth, currently do and should carry heavier weight.

Takeaway: Ohio’s final, “summative” rating is very user friendly and helps avoid misinterpretation.

Letter grades. Along with fifteen other states, Ohio adopted an A-F rating system, first implementing it in 2012-13. Because most of us have received A-F grades, almost everyone understands that an “A” indicates superior accomplishment while an “F” is a red flag and clear distress signal. Due to the widespread use of letter grades, they offer maximum transparency around results. As with overall ratings, the A-F system also helps users avoid misinterpretation. For instance, under Ohio’s former rating system, schools could receive the vague “continuous improvement” rating even if they performed worse than the year before. Other descriptive labels risk becoming euphemisms used to soften troubling results: “Below Expectations,” for example, has nowhere near the sense of urgency of an “F.”

Takeaway: While various rating systems exist, none can match letter grades in terms of public transparency. In turn, they hold the most promise of engaging families and communities in celebrating well-earned success or sparking transformation when necessary.

Achievement and growth. To its credit, Ohio has made measures of student achievement and growth—two distinct views of school quality—the bedrock of state report cards. Achievement considers how students fare at a single point in time and includes measures such as the performance index and scores on ACT/SAT exams. Growth, on the other hand, looks at the trajectory of students’ academic performance over time. To capture this type of growth, Ohio has long used “value-added” measures which track learning gains regardless of where students begin the year on the achievement spectrum. Value-added results form the basis of the Progress component and, starting with 2017-18 report cards, are now included in Gap Closing.

Takeaway: By featuring both achievement and growth prominently, Ohio offers a fairer, more balanced picture of whether students meet state standards at a particular moment in time and whether students are making progress.

Recommendations for Improvement

Despite these crucial strengths, we believe that there is still room to improve the state report card. In our December 2017 report Back to the Basics, which I believe you were provided at a previous meeting, we outlined a few suggestions that would further enhance the transparency and fairness of Ohio’s report cards.

At a high level, our key recommendations include:

- Streamlining the report card by removing subcomponent ratings and assigning only an overall rating and five component ratings—Achievement, Progress, Gap Closing, Graduation, and Prepared for Success.

- Simplifying and renaming the Gap Closing component.

- Placing a greater emphasis on growth measures in the overall rating to provide a fairer picture of quality among higher-poverty schools.

In the following remarks, I’ll touch on each report card component. They generally follow our 2017 analysis, but I’ll also include some further thoughts on a few topics that were not as prominent two years ago.

Achievement. This component provides a point-in-time look at how students perform on state exams. It includes both the performance index—a weighted measure of proficiency that awards additional credit when students achieve at higher levels—and indicators met, a subcomponent that focuses primarily on proficiency rates. We recommend eliminating indicators met and basing the Achievement rating solely on the performance index. Instead of a binary proficient/not-proficient metric, the performance index offers a more holistic view of achievement across the spectrum. This creates an important incentive for schools to help students at all achievement levels reach higher goals, rather than encouraging schools to focus narrowly on students just above or below proficient. If Ohio removes indicators met, the state should continue to report—but not grade—proficiency rates for each district and school.

We also strongly support the current design of the performance index, specifically the weighting system tied to each achievement level. We have deep concerns about proposals to change the weights in a way that would allow a small segment of high-achievers to mask the broader achievement struggles in a district or school—something that could be done, for example, by increasing the weight on categories such as Limited and Basic or adding a new achievement level.

Takeaway: We recommend eliminating indicators met and basing the Achievement rating solely on the performance index. We also strongly support the current design and weighting of the performance index.

Progress. This component contains four value-added measures—an overall value-added rating and three subgroup ratings. These measures gauge schools’ impacts on learning regardless of students’ prior achievement, which puts schools serving students of varying backgrounds on a more neutral playing field. In Back to the Basics, we suggested removing the subgroup value-added measures and transferring two of them—gifted and students with disabilities—to the Gap Closing component, thus offering a clearer view of schoolwide student growth via the Progress rating. We continue to believe Ohio should adopt those changes. Two additional matters regarding value-added that were not discussed in great detail in our 2017 paper are worth touching upon.

- Years of data. There has been debate over whether to use a one- or three-year average value-added score to determine growth ratings. The state’s current method, multi-year averaging, helps avoid large changes in these ratings from year-to-year—schools are less likely to swing from “A” to an “F” as a result—but it also means using less current data. We recommend that the state split the difference and use a weighted average score, placing 50 percent weight on the current year value-added score, and 25 percent each on the two prior years.

- Grading scale. The grading scale used to translate value-added scores into ratings has been heavily discussed, and was altered under House Bill 166. We believe that the HB 166 modifications were a poor solution to the larger challenge of anchoring ratings on “value-added index scores,” measures of statistical certainty that are often confused as indicators of the “amount” of growth that students make. In our view, Ohio should consider shifting away from index scores and instead focus on the actual gain (or loss) made by the average student in a district or school. Done well, moving in this direction has the potential to strengthen public and educator understanding of the growth results—it should better answer the more commonly asked question “how much growth did students make?”—and would allow Ohio to make a fresh start in its approach to translating growth data into ratings. It’s important to note that the issues surrounding the grading system do not indicate problems with the underlying statistical model, but rather reflect challenges in translating statistical results into a rating.

Takeaway: We recommend removing the subgroup value-added measures and transferring two of them—gifted and students with disabilities—to the Gap Closing component. We also recommend using a weighted average score to determine growth ratings and focusing on actual gains in the grading scale.

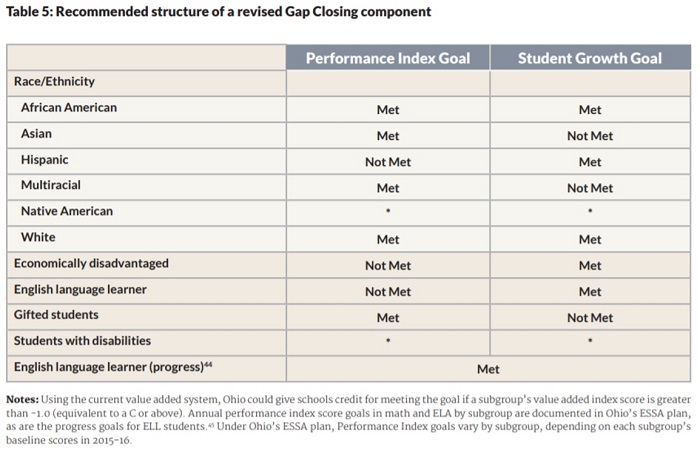

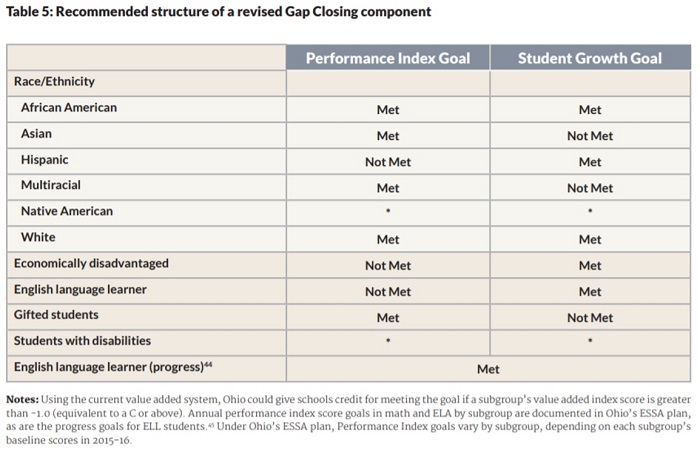

Gap Closing. This component serves the purpose of ensuring that students from specific subgroups—students with disabilities, English language learners, economically disadvantaged students, and racial/ethnic groups—all receive a quality education. The current design of the component relies on a subgroup’s performance index, graduation rates, and, as of 2017-18, their value-added scores.

The calculations within this component remain complex and a little difficult to follow. In Back to the Basics, we suggest a somewhat simpler component that would offer a more transparent picture of subgroup performance. The table appended—from Back to the Basics—contains an illustration of our proposed framework, which relies on a series of indicators allowing users to see whether subgroups achieved performance index and growth targets. In that report, we also suggested that Ohio change the component name from Gap Closing to “Equity.” The reasons are twofold: 1) the component includes a few traditionally high-achieving subgroups and 2) while closing achievement gaps remains critical for Ohio, the component itself doesn’t necessarily capture whether gaps are closing. For instance, Columbus City Schools received a “B” in Gap Closing in 2018-19 but its black-white achievement gap in math increased by 0.5 points on the performance index and narrowed by just 0.2 points in ELA. The term Equity would better convey the component’s aim: To ensure that all subgroups are meeting state academic goals.

Takeaway: We recommend simplifying the component to offer a more transparent picture, and renaming the component “Equity.”

Prepared for Success. A central aim of K-12 education is to prepare students for success after high school. To this end, Ohio implemented Prepared for Success as a graded component starting in 2015-16. It has a two-tiered structure that, at the basic level, awards credit to schools when students earn remediation-free scores on the ACT or SAT, accumulate at least 12 industry credentials points, or attain an honors diploma. In addition, schools may earn “bonus points” when students who meet any of the primary targets also pass AP or IB exams or earn college credit via dual enrollment. Over the past year, there has been discussion around the design of Prepared for Success, including whether to shift to a single tier structure, incorporate additional measures, and even potentially eliminating it.

A few general comments. First, we believe that Prepared for Success merits inclusion in Ohio’s report card. Communities deserve to know whether young people graduate high school truly ready for their next steps in life. Second, policymakers should be careful not to jam too much data into the component and create an immense, complicated measure. Third, for formal report-card purposes, Ohio should depend on reliable data and use metrics that are difficult to game and avoid using subjective measures like readiness seals. Fourth, we should be mindful that post-secondary outcomes—e.g., college enrollment or apprenticeships after high school—are not necessarily in the control of K–12 schools. That is likely why Ohio reports college enrollment and completion rates within this component but refrains from rating schools based on those data.

With this in mind, we recommend that policymakers approach any revisions to Prepared for Success with care. The purpose of the component—to provide a view of graduates’ readiness—and the underlying metrics are sound. We would, however, support the following avenues for refinement. First, Ohio should incorporate military readiness and enlistment as an indicator of success. Second, we recognize that the ratings distribution on Prepared for Success (largely D’s and F’s) creates less differentiation than might be desired. To this end, we would support a revision to the grading scale in a way that maintains its rigor but also creates more differentiation. Third, Ohio could incorporate an improvement dimension that provides districts and schools with low baseline readiness rates a chance to demonstrate success, while also offering an incentive to schools to help more students achieve rigorous readiness targets.

What we would strongly discourage is eliminating Prepared for Success or weakening it by giving schools low-level “pathways” for earning credit. The last thing Ohio needs is a duplicative component that is indistinguishable from the less rigorous Graduation component.

Takeaway: We recommend avoiding the inclusion of subjective measures, like readiness seals, but adding military readiness and enlistment as an indicator of success. We also suggest revising the grading scale and incorporating an improvement dimension.

Graduation Rate. Speaking of graduation, this component currently includes the four- and five-year graduation rate as graded subcomponents, along with a composite rating. We recommend that the state award a single Graduation rating that combines (but does not issue separate grades for) the four and five year graduation rates. We also support efforts to calculate, and potentially include on report cards, a graduation rate that accounts for students who transfer schools. Though Ohio may not be able to replace the traditional adjusted-cohort calculation, this calculation would ensure that high schools are held accountable for graduation in proportion to the time in which a student was enrolled.

Takeaway: We recommend that Ohio base schools’ Graduation rating on a combination of its four-year and five-year graduation rates, without issuing separate ratings for each. We also support efforts to calculate, and potentially include on report cards, a graduation rate that accounts for students who transfer schools.

K-3 Literacy. Early literacy remains the foundation for later academic success. But with the exception of the KRA for incoming Kindergarteners, the state does not require schools to assess early elementary students in the same way as students in grades 3-8 and high school. In the early grades, schools may select among a variety of reading diagnostic exams, thus making school ratings more tenuous under this component. Moreover, state law allows certain districts and schools to receive no rating on K-3 Literacy, and the measure focuses entirely on a subset of students—those deemed by their school to be “off-track” —rather than literacy among all students. While we strongly support Ohio’s efforts to improve early literacy, including the Third Grade Reading Guarantee, we recommend that the state either explore ways to significantly strengthen the K-3 measure, use it in a more limited way (for example, as a rating that only applies to K-2 schools), or remove it from the report card.

Takeaway: We recommend that the state either explore ways to significantly strengthen the K-3 measure, use it in a more limited way—for example, as a rating that only applies to K-2 schools—or remove it from the report card.

Additional Thoughts

Finally, a few words about several specific issues, concerns, and ideas that you may hear about in the coming weeks.

Data dashboards. As many of you know, House Bill 591 was introduced in the last General Assembly. It called for a “data dashboard” system that would display a blizzard of dense education statistics but would provide no ratings that provide context and meaning for everyday Ohioans. We firmly believe that a dashboard system would fail to provide the transparent, actionable information that Ohio families and communities deserve. Quite simply, clarity and transparency would be lost in a move to a data dashboard.

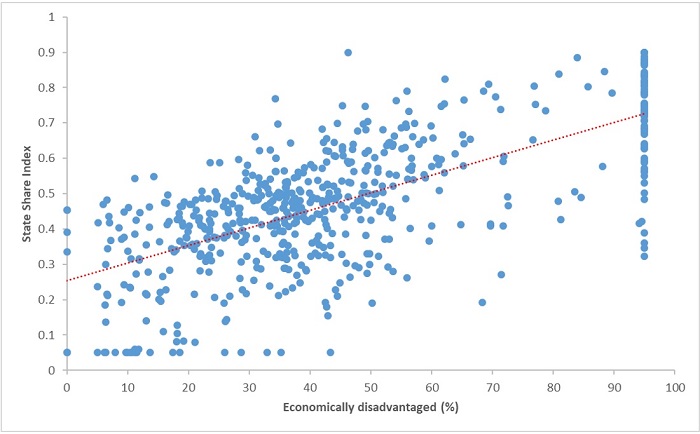

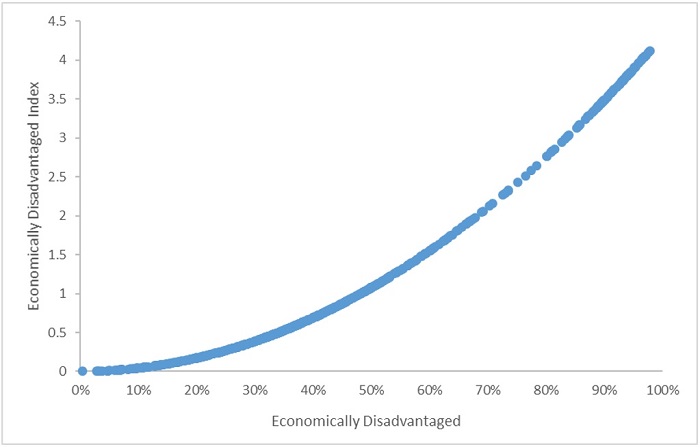

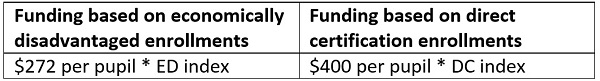

Demographics. One of the common critiques of the current report card system is that its results reflect too heavily the backgrounds of the students enrolled in schools. We certainly share that concern when it comes to achievement-based measures such as the performance index and even Prepared for Success. That’s why we recommend a balance between status-type measures and student growth, even somewhat favoring the latter in the overall rating formula. Three additional things should be kept in mind regarding demographics:

- First, we must affirm through our report card system that we truly believe that all students can learn. It’s not fair to low-income students or children of color to set lower performance bars—the troubling “soft bigotry of low expectations”—just to inflate their schools’ ratings.

- Second, Ohio should not be in the business of sweeping achievement gaps under the rug. It’s true that high-poverty schools face significant challenges, and their achievement-based ratings should be viewed in context. But hiding the fact that few students in a school can read or do math at grade level is neither transparent nor fair to students who need the extra help.

- Third, we must remember that Ohio places a strong emphasis on the more poverty-neutral growth measures. Both the Progress and Gap Closing components incorporate value-added, and together these components account for roughly 35 to 65 percent of a school’s overall rating. Due to the weight being placed on value-added, quality high-poverty schools are beginning to stand out. For example, on the 2018-19 report card, 40 percent of Ohio’s high-poverty schools received a very respectable “C” or above as their overall rating.

Choose your own adventure. We’ve seen various proposals over the years that would rely on the higher of two results—a “choose your own adventure” type policy. This is wrong for a couple reasons. First, it can mask low performance. For example, if schools were able to drop their performance index score, it would hide the achievement struggles of students needing to make up significant ground. Second, it’s pretty easy to argue that proposals such as these are designed to make schools look better, rather than genuine attempts to improve the functioning of the report card. We all want highly rated schools. But top ratings should be earned, not given through shortcuts.

Non-academics. We all know that schools do lots more than academics. They help young people build character, learn teamwork, and bear increasing responsibility. Though critical, these intangible non-academic traits are incredibly challenging to gauge in a reliable, objective manner. Most experts in the field warn against incorporating them into formal accountability systems. We concur.

Conclusion

Ohio’s report card has long been central to a transparent, publicly accountable K-12 education system. In the coming weeks, you’ll hear a number of opinions about state report cards. But you should go into this knowing that despite some areas that could be improved, your predecessors have built a generally strong report card. If you carefully evaluate the report card through the lenses of transparency, fairness, rigor, and consistency, I believe that an even stronger framework will emerge.

Thank you for the opportunity to speak, and I welcome your questions.

* * * * *

Appendix