Note: This is the seventh in a series of blog posts on school funding in Ohio; for the previous posts, see here, here, here, here, here, and here.

How to fund low-income students is one of the big questions in Ohio’s ongoing school funding debate. While the plan put forward by Representatives Bob Cupp, John Patterson, and a group of district officials would spread more than a billion additional dollars in state aid across Ohio schools, concerns have been raised that it doesn’t steer nearly enough money to the state’s neediest schools.

For instance, a highly detailed analysis by Howard Fleeter indicates that high-poverty “Big Eight” urban districts would see an average increase of $1,115 per pupil under a fully implemented plan, poor rural districts would gain $1,158 per pupil, and wealthy suburban districts would see a bump of $906 per pupil. Not satisfied by this modest advantage for poorer districts, the Akron Beacon Journal editorial board urged the state “to do better.”

Though not featured in Fleeter’s analysis, Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools, despite serving predominantly low-income students and already shortchanged in the overall funding system, would fare dismally under the plan. The Big Eight charters would see an increase of just $758 per pupil—even less than wealthy suburban districts. Worse yet, charter amounts would be frozen after a couple years, while districts would continue to gain funds after full implementation because the plan calls for adjustments based on inflation. Meanwhile, private-school scholarships, which also serve mainly disadvantaged students, would not rise at all—a $0 increase.

There are a number of plausible reasons why the Cupp-Patterson plan doesn’t concentrate dollars on poorer schools.

- With the exception of school choice funding, Ohio’s overall system is already pretty fair to high-poverty schools. Perhaps it’s harder to justify sending more state funds to them.

- The Cupp-Patterson plan seeks to eliminate “caps,” which suppress funding increases for some wealthy (but growing) school districts. While removing caps is a worthwhile endeavor, doing so likely soaks up a significant portion of the funding hike sought under the proposal.

- Its icy approach to choice programs might reflect the interests of the district officials who served as plan developers.

- As Representative Patterson noted earlier this year, he and his colleagues have “been unable to fully define what ‘economically disadvantaged’ is.”

Given the questions around the way in which the plan funds low-income students, it’s worth reviewing how Ohio currently provides extra resources to schools that serve needier students. We’ll also consider some options that legislators could pursue to strengthen the state’s approach to funding low-income students. (Wonk warning: This piece gets into the weeds on some issues, but the details are important as legislators weigh alternatives.)

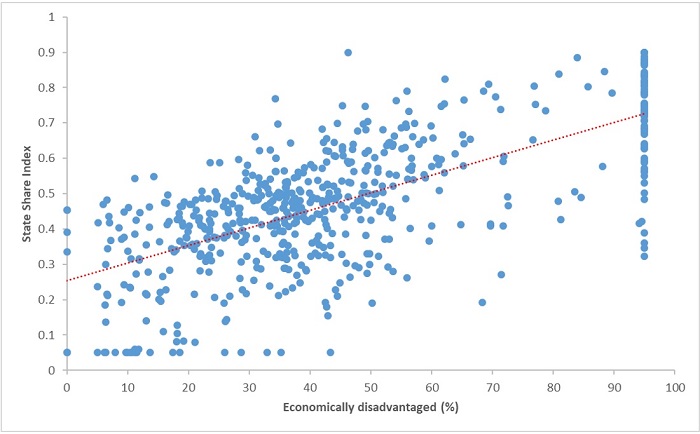

Option 1: Funnel more dollars through the Opportunity Grant

Through its current funding formula, Ohio already delivers more state aid to its poorest school districts. The core of this system is the Opportunity Grant, which in FY 2018 drove 58 percent of state foundation aid to districts. The allocation of these funds is based on the “state share index” (SSI), which takes into account a district’s property wealth, and in about half of all districts, resident income too. The SSI, whose values range from 0.05 to 0.90, is multiplied by the “base amount” for the Opportunity Grant—currently $6,020 per pupil—so that poorer districts receive larger allocations, while wealthier districts receive less because they can raise more revenue locally.[1] As Figure 1 indicates, the SSI generally correlates with districts’ ED rates, meaning that the Opportunity Grant will tend to allocate more state funds to districts with the most disadvantaged pupils.

Figure 1: Relationship between economically disadvantaged students and state share index, Ohio school districts, FY 2019

Source: Ohio Department of Education

Thus, one way Ohio could direct additional state dollars to districts with more low-income students is to simply funnel more dollars through the Opportunity Grant. For instance, if Ohio raised the base amount to $6,500 per pupil, a high-poverty district such as Dayton, which has an SSI of 0.88, would see an increase of $422 per pupil. Conversely, wealthy districts would see smaller increases: A district with an SSI of 0.15, for example, would see a bump of just $72.[2] In addition, increasing the base amount and adding a multiplier to it would also better support public charter schools, which receive the full base amount because they have no local taxing authority. Nevertheless, as Figure 1 indicates, the correlation between districts’ SSI and ED rates is not one-to-one—nor is that result likely because the SSI isn’t based on ED data. So while this remains a viable option, some of the funds would be misdirected if the goal is to effectively steer extra resources to low-income students.

Option 2: Enhance the ED component with funding based on direct-certification counts

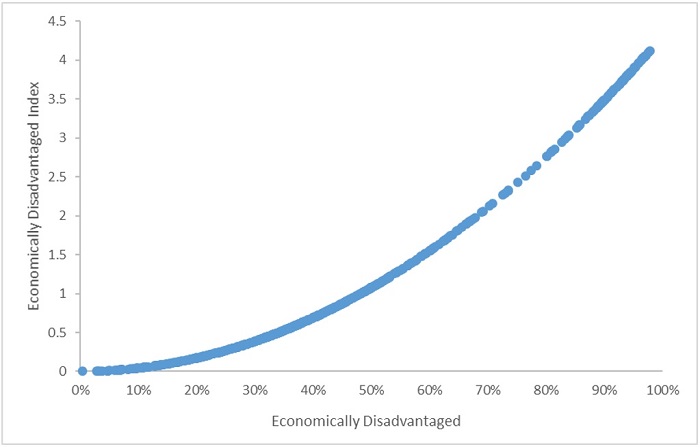

To provide extra resources in a direct manner to districts serving a high proportion of low-income students, Ohio includes a funding component based on ED rates. This funding stream, often considered part of the state’s categorical “add-ons,” is far smaller than the Opportunity Grant—making up just 5 percent of the overall foundation program. This component doesn’t rely on the SSI. Rather, it’s based on the ED index, whose values range from 0 to 4.1, and is designed to deliver more aid to districts with more concentrated student poverty.

Figure 2 displays the clear, albeit mechanical, relationship between districts’ ED rates and index values (the curve is due to a square term in the index). The ED index is then multiplied by a base amount of $272 per pupil, resulting in more dollars flowing to higher-poverty districts. For instance, a district with an ED index of 3.5 would receive $952 per pupil in extra support through this funding stream. Public charter schools are eligible to receive these funds, too, and their amounts are based on the ED indexes of students’ home district.

Figure 2: Relationship between economically disadvantaged students and ED index, Ohio school districts, FY 2019

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: The figure displays each district’s percentage of ED students, including both district and charter students who reside in the district (the index is based on students attending both types of schools).

At first blush, the ED component appears to be a natural lever to deliver more aid to districts serving low-income students. But here’s the rub: As discussed in an earlier piece—and probably alluded to in Representative Patterson’s comment—a growing number of Ohio students are being misclassified as “economically disadvantaged” due to their districts’ or schools’ participation in a federal subsidized meals program known as Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). Under this program, students are universally eligible for free and reduced-priced lunch (FRPL)—the basis for ED identification—and thus CEP leads some more affluent students to be incorrectly deemed ED. In my estimation, approximately 65,000 students are misidentified, about the size of the Cleveland and Toledo school districts combined.

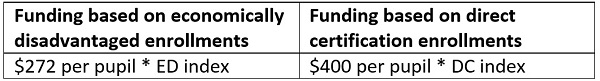

In what developers have called a “placeholder” amount (until a proposed study on ED identification and costs is finished), the Cupp-Patterson plan would increase the ED base amount from $272 to $422 per pupil. That’s probably OK for now. But given the challenges of ED identification in light of CEP, what’s likely needed is an alternative mechanism to deliver funds in a more accurate way. Basing funding on direct certification (DC), a direction that a few other states have gone, is a promising option. Using administrative records, DC identifies low-income students based on their households’ participation in means-tested programs such as TANF, SNAP, or Medicaid, along with students flagged as in foster care, migrant, or homeless.

This method has the advantage of not misclassifying higher-income students who attend CEP schools. And because the income thresholds are lower to participate in these means-tested programs—at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty line versus FRPL’s eligibility cutoff of 185 percent—DC captures students who likely face the greatest educational challenges. However, DC may undercount some low-income students whose families decline to participate in means-tested programs, and it would require some cross-agency heavy lifting to properly link records.

Care would also need to be taken to incorporate a new measure of student poverty into the existing system. Because the income thresholds differ under ED and DC methods, some districts and charters may lose funding if Ohio suddenly replaced one method for the other. A range of implementation options exist, but perhaps the most straightforward (though requiring additional funds) would be to create a two-tiered structure that stacks DC-based funding on top of the existing ED dollars. The table illustrates what that could look like.

This approach would have the following advantages:

- Drive more resources to districts and charters that educate students from Ohio’s lowest-income families.

- Continue to provide extra aid for students in households between 133 and 185 percent of the federal poverty line.

- Avoid a potential “hold harmless” provision, since funds are being added to the component.

- Deliver some extra funding under the ED tier for low-income students whose families don’t participate in TANF, SNAP, or Medicaid.

- Enable CEP districts to allocate funds to their neediest schools based on DC counts. (They currently report 100 percent ED across all schools.) The state could even require these funds to automatically flow to the schools in which DC students attend.

Option 3: Use the new Student Wellness and Success funding stream

In a new dimension of school funding starting this year, Ohio now provides $276 million in extra funds to districts and charters that aim to support students’ non-academic needs. These dollars must be spent in specific ways, and schools have to engage community partners as well. Perhaps seeking to avoid the problems of defining student poverty via ED status, the allocation of these funds is based on U.S. Census Bureau estimates of districts’ percentage of children whose family incomes are at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty line (charter funds are again based on students’ home district data). Much like the Opportunity Grant and ED funding, districts with higher poverty rates receive larger per-student subsidies than wealthier districts. The exact calculation is somewhat complicated, but it generally allocates between $20 and $250 per pupil depending on the childhood poverty rate of the district.[3]

Although census data have many useful applications, they have some drawbacks when used in a school funding context. First, it’s not based on the actual enrollment of students attending public schools—it’s all children ages zero to eighteen. Thus, it would reflect children under the kindergarten age, along with homeschooled and non-public-school students. Second, the data are collected via survey samples, resulting in estimates of poverty that in some cases differ quite substantially from ED counts. While districts’ census and ED data generally correlate, the rates diverge by more than 10 percentage points among a fairly large number of Ohio districts.[4] In most cases, the ED rates are probably more reliable measures of districts’ student demographics, since they are based on actual headcounts. Third, because the census doesn’t produce data at an individual school level, it can’t help us gauge poverty across schools. Thus, it’s hard to imagine a system that effectively drives dollars to high-poverty schools based on census data.

Though basing funding on census data is a reasonable short-term solution, it’s something only two states currently do and is likely not ideal over the long haul. The Student Wellness funds have praiseworthy aims, but legislators should tread carefully when it comes to using this funding stream to deliver extra aid to Ohio’s poorest schools.

* * *

The Cupp-Patterson plan gets a few things straightened out in Ohio’s funding system. But as some critics have suggested, it doesn’t have an especially strong focus on driving extra state resources to the neediest students, whether they attend district or charter schools or use a scholarship to attend a private school. If state legislators seek to make funding low-income students an even greater priority, they have options within the existing framework. It doesn’t take a complete overhaul of the system to make it happen.

[1] To receive state aid, districts must levy an effective property tax rate of at least 20 mills (or 2 percent). In districts with higher property values, this rate will generate more funding.

[2] The Cupp-Patterson plan would eliminate the SSI and instead allocate the “core foundation funding” (the analog to the Opportunity Grant) based on an entirely new model. Briefly, it would first calculate a base amount, determined by a calculation of “input” costs, which varies by district, and then multiply a district’s property wealth and income data by a value ranging from 2.0 to 2.5 percent. This would yield a “local capacity amount” that is then subtracted from the base amount to generate the core foundation funding of the district. This method would likely continue to allocate funds in a “progressive” manner, but it’s not clear how it compares to the SSI in terms of allocating dollars to districts with higher student poverty.

[3] These amounts will increase in FY 2021 to a range between $30 and $360 as the appropriation for the program rises to $398 million next year.

[4] Among the 539 districts that did not report 100 percent ED in FY 2019, 168 had an ED rate that differed by more than 10 percentage points from their census-reported poverty rate.