Career-technical education integrates traditional academic skills and knowledge with technical and job-specific skills. Over the last several years, Ohio policymakers have prioritized expanding access to career-technical education, funded programs to help students earn credentials, and bolstered initiatives related to work-based learning.

These are commendable efforts. But Ohio’s career-technical sector is increasingly complex. The average student and taxpayer do not realize all it has to offer. The policy brief below seeks to rectify that by providing a broad overview of the career-technical opportunities available to Ohio high schoolers, as well as the benefits of participating.

Introduction

A few decades ago, Career-Technical Education (CTE) was considered a path to nowhere. Typically called “vocational education” or “vo-tech” at the time, these courses were too often seen as a dumping ground for academically struggling students who were deemed incapable or unwilling to participate in traditional academic courses.

Recognizing that today’s students deserve better, that schools have an obligation to better prepare their students for the future, and that employers and the broader economy depend on a skilled workforce, state leaders in Ohio and elsewhere have worked hard to transform CTE programs and courses. Traditional academic skills and knowledge are now integrated with technical, job-specific skills that aim to prepare students for careers in high-tech, in-demand fields. At the high school level, effective CTE programming can provide students with the opportunity to earn industry-recognized credentials and postsecondary degrees. It can open the door to entry-level jobs. And it can also connect students to higher education programs, typically through community colleges that offer specialized training within a career field.

Ohio now has a vibrant CTE sector, and tens of thousands of high school students are availing themselves of these options. In 2021–22, over 135,000 secondary students were CTE participants, meaning they completed at least one CTE course that year. Of these, roughly 83,000 were CTE concentrators—students who earned two or more credits in a single career pathway. Since 2014, the number of high school students earning industry-recognized credentials has also steadily increased, from just under 9,000 credentials earned by the graduating class of 2014 to over 78,000 credentials among the class of 2022. The state budget bill passed in July 2023 includes a quarter billion dollars in new funding to expand the capacity of CTE providers, increase student participation in high-quality programs, and bolster initiatives like the Innovative Workforce Incentive Program, which aims to increase the number of students who earn qualifying industry-recognized credentials in “priority” industry sectors.

One key reason why participation and credential attainment have increased in Ohio is because beginning in 2014, state law required every public school (with a few exceptions) to ensure that students in grades 7–12 have the opportunity to enroll in CTE programming in state-approved career fields. How students access these opportunities—and how many options they have— depends primarily on where they live and what school they attend. There are also additional opportunities available through programs like College Credit Plus, Ohio’s statewide dual enrollment system.

But Ohio’s CTE system still needs work. It’s uneven and complex, which can lead to confusion and missed opportunities. The average student and her family may not realize which programs and courses are available, or may be unaware of the many benefits of participating in CTE. The average taxpayer may not realize how important it is for Ohio to continue improving, expanding, and investing in its CTE programs.

In this paper, we provide a broad overview of the various ways in which Ohio high schoolers can participate in CTE, and the benefits they can expect to derive from their participation.[1] Although there are plenty of areas across the sector that are ripe for improvement, recommendations for addressing these issues will come later, via additional in-depth analyses. This paper is designed to function merely as a directory of the state’s various CTE pieces and parts, so that policymakers and advocates have a common foundation—as simplified as possible, and all in one place—from which to move forward.

Who provides CTE and what types of opportunities do students have?

In Ohio, CTE programming is delivered through Career-Technical Planning Districts (CTPDs). These are distinct organizational structures that must meet state requirements and standards to offer CTE programming to students. There are three structures for CTPDs:

Comprehensive CTPDs

These are single school districts that provide CTE programming at schools or career centers located within district boundaries. Typically, students access this programming the same way they access traditional academic classes, as CTE courses are part of the district’s available course offerings. Comprehensive CTPDs are governed by the same local school board and superintendent responsible for operating the traditional district. They are funded via local taxes collected for the district, as well as through state and federal subsidies.

For example, the state’s largest district, Columbus City Schools, operates a comprehensive CTPD that offers nearly forty CTE programs to Columbus City Schools students, but also to students enrolled in other districts, charter, and STEM schools. It includes two career-technical centers that serve both juniors and seniors: Columbus Downtown High School, which is a full-day career center and offers both academic and CTE courses, and the Fort Hayes Career Center, which offers half-day CTE courses in certain career pathways.

Compact CTPDs

Compact CTPDs are groups of districts that collaborate and combine resources to offer CTE programming. Typically, different programs and courses are offered at various schools and buildings within member districts.

For example, the Six District Educational Compact in northeast Ohio is comprised of six suburban districts: Cuyahoga Falls, Hudson, Kent, Stow-Munroe Falls, Tallmadge, and Woodridge. It offers students who attend any of these districts a menu of twenty-eight CTE programs from which to choose. This includes programming and software development, athletic health care and fitness, an aeronautics careers academy, and a biotechnology academy. If a student is interested in participating in a program offered at a building other than the one they currently attend, they can attend half the day in their home school and the other half at their CTE school. Bus transportation is provided, and students can still participate in extracurriculars, like sports or marching band, in their home schools. Compact CTPDs like the Six District Educational Compact are governed by the board and superintendent of a lead district, which is always one of the compact’s member districts. They are funded via local taxes collected by participating districts and through state and federal subsidies.

Joint Vocational School Districts (JVSDs)

These districts operate as independent school districts and primarily offer CTE programming. Each one serves a geographic area containing adjacent school districts. Districts that do not directly provide CTE programming for their students—meaning they are not a comprehensive CTPD and do not participate in a compact CTPD—make CTE programming available to their students by partnering with a JVSD. Students can attend a JVSD full or part-time. JVSDs typically provide programming in a dedicated CTE-focused building, though they can also offer programming within member schools through satellite programs. For example, the Jefferson County JVSD serves several traditional districts as well as Steubenville Catholic Schools. It offers students fifteen CTE programs and boasts a full-service restaurant operated by its culinary arts students.

Students who aren’t enrolled in one of the districts served by the JVSD can still attend the JVSD if it has adopted a policy permitting open enrollment, as several in Ohio do. Because JVSDs are independent from traditional public districts, each one is governed by its own board. By law, their boards have many of the same powers, duties, and authority over management and operation as do traditional districts. They consist of appointed representatives who serve three-year terms, and can either be current elected board members from the participating district, or individuals with appropriate experience or knowledge. JVSDs are funded through local taxes and levies in participating counties, but also by state and federal subsidies.

Common features of CTPDs

Ohio has twenty-five comprehensive CTPDs, fifteen compact CTPDs, and forty-nine JVSDs.[2] Every public high school in Ohio—including charter and independent STEM schools—must be part of one of these CTPDs. As such, the CTE programming available to high schoolers varies across the state and depends on the CTPD option chosen by a student’s school. There are, however, some common features across all CTPDs.

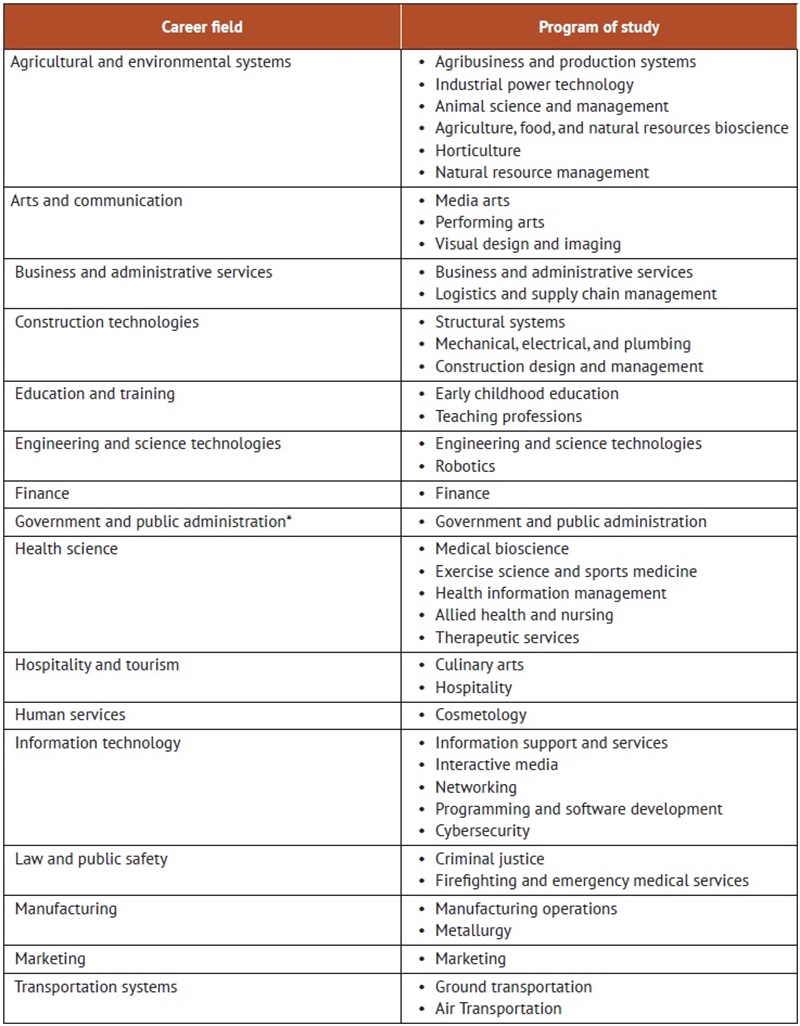

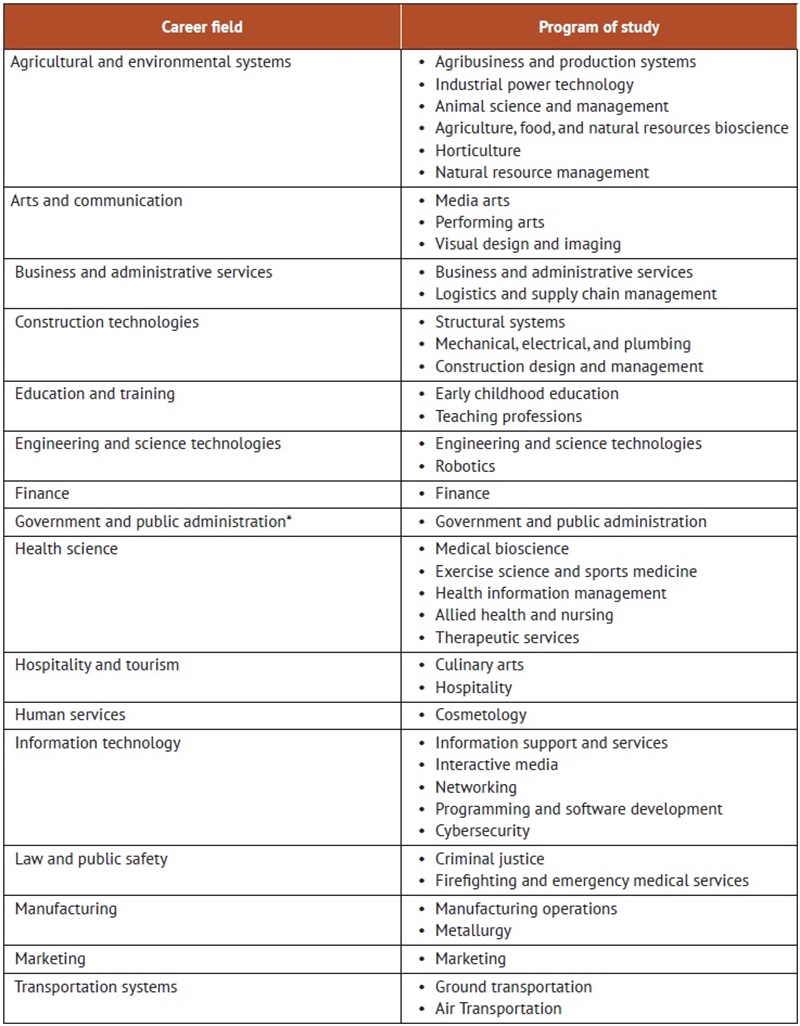

Programming

State law requires that CTPDs provide students with courses representing twelve programs in at least eight career fields. CTPDs with fewer than 2,250 students enrolled in grades 7–12 are only required to provide courses in ten different programs in at least eight career fields. In total, Ohio supports thirty-nine programs of study across sixteen approved career fields. The state establishes content standards for each career field, as well as course titles, descriptions, and outlines. The sixteen fields and their associated programs of study are listed below.

* Ohio currently has no secondary CTE programs in this career field.

* Ohio currently has no secondary CTE programs in this career field.

Work-based learning

One key feature of CTE is that it offers students the ability to get hands-on experience in their chosen career field via work-based learning. Although the specific work-based learning opportunities available to students depend on the CTPD they attend and the career field and program they choose, the state has established several guiding principles for these experiences. For example, experiences must occur at a work site and must be supervised by an instructor and an employer or business mentor. The state also recognizes several types of work-based learning, including internships and apprenticeships.

Alongside what’s offered through CTPDs, several state-funded programs help incentivize employers to create additional opportunities for students. For example, the High School Tech internship provides high school students with work experience in technology-related roles. Under this program, employers who hire high school interns in tech-related roles can be reimbursed for wages if students are employed for a minimum number of hours and are paid at least $12 per hour. The state also offers a tax credit certificate program for employers that offer work-based learning experiences to students.

Assessments

Students enrolled in CTE pathway programs are required to take end-of-course exams for each course in which they are enrolled. These exams are designed to cover the material identified in course outlines provided by the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce. The department also annually updates a CTE assessment and program matrix.

CTE exams are developed and administered by Ohio State University’s Center on Education and Training for Employment (CETE) via a proprietary system called WebXam. The majority of pathway programs have established end-of-course tests. However, because the state has been in the process of transitioning to a new model of testing in recent years, there are a few that still await development of their exams. There are three levels that CETE uses to delineate student performance: nonproficient, proficient, and advanced.

College Credit Plus

College Credit Plus (CCP) is a state-run, state-funded dual-enrollment program that offers academically eligible students in grades 7–12 the opportunity to earn postsecondary credit by taking college courses for free before high school graduation. State law requires all public schools serving eligible students to participate in CCP. This means that every student who meets CCP eligibility guidelines can access available postsecondary CTE courses through CCP, regardless of their assigned CTPD. The percentage of students statewide who have enrolled in CCP technical courses—defined as those that are part of an associate degree program of technical education—has modestly increased over the years. Roughly 13 percent of courses taken during 2015–16 were technical, compared to 15 percent during 2021–22.

The benefits of participating in CTE

Students who participate in CTE can benefit in a variety of ways depending on their chosen program and career field. Potential outcomes include the following.

Industry-recognized credentials

One of the key benefits of CTE is the opportunity for students to earn industry-recognized credentials that demonstrate their knowledge and skill mastery. Credentials verify a student’s qualifications and competence via a third-party, and signal to employers that job applicants are well–prepared. They can be prerequisites to certain jobs, and can also boost earnings and employment.

The Department of Education and Workforce maintains an approved list of industry-recognized credentials that high school students can earn. The approved list includes the following types of credentials:

Certificates are earned when students successfully complete a training, course, or series of courses. Although certificates are issued for specific skills or competencies within one or more industries or occupations, they don’t always have a meaningful impact on a student’s job prospects. Some certificates may be part of hiring criteria but not associated with critical job tasks, or may be viewed by employers as desirable but not required. Certificates can also be awarded for attendance or participation.

Certifications indicate a student’s mastery of specific knowledge, skills, or processes that are measured against a set of accepted industry standards. Certifications are not tied to a specific educational program, but are typically awarded to students via an assessment or a validation of skills in cooperation with a business, trade association, or other industry group. To maintain a certification, students are usually required to meet ongoing requirements.

Occupational licenses are awarded by state government agencies and are often required for students to obtain specific jobs or positions.

Students can earn industry-recognized credentials by completing a comprehensive CTE program, by completing courses that integrate the content needed to obtain the credential, or via a state program dedicated specifically for students in their senior year of high school. Every credential is assigned a point value between one and twelve. Point values are based on employer demand and/or state regulations and often signal the significance of the credential. For example, within the health career field, credentials for CPR first aid or blood-borne pathogens compliance training are each worth one point. In that same career field, earning a state-issued license through the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy to become a Certified Pharmacy Technician is worth twelve points.

High school diploma

In addition to gaining specific job skills, students can use the CTE credits and experiences they’ve accumulated to meet Ohio’s graduation requirements. State law provides students with multiple pathways to demonstrate their academic competency and earn a diploma, and one of those pathways focuses on career experience and technical skill. It requires students to complete two of the following seven options. One of the completed options must be from the “foundational” category.

Foundational options

- Earn a cumulative score of “proficient” or higher on three or more WebXams in a single career pathway;

- Earn a twelve-point approved industry-recognized credential, or a group of approved credentials totaling twelve points in a single career field;

- Complete a pre-apprenticeship program recognized by the Ohio State Apprentice Council (OSAC), complete an OSAC registered apprenticeship in the student’s chosen career field, or, if the program requires a student to be eighteen or older, show evidence of acceptance into an OSAC registered apprenticeship program after high school;

- Obtain a state-issued license, such as an Ohio Commercial Driver’s License, for practice in a vocation that requires an examination.

Supporting options

- Complete a 250-hour work-based learning experience with evidence of positive evaluations;

- Earn the workforce readiness score on WorkKeys, which is a career assessment created by ACT to measure foundational skills required for success in the workplace;

- Earn the Ohio Means Jobs-Readiness Seal, which requires students to demonstrate proficiency in fourteen state–identified professional skills evaluated by three mentors from school, work, or the community.

College credit

Another benefit received by students who complete CTE courses through College Credit Plus is simultaneously earning secondary and post-secondary credit. But CCP isn’t the only way that students can earn college credit for the CTE courses they complete. They can also do so through articulation agreements.

Articulation agreements are arrangements between secondary schools and colleges or universities that link high school–level courses to similar college courses. These agreements can be narrow—focused on a partnership between a single secondary school and a university—or they can extend statewide. Obtaining credit is a relatively simple process: Students request college credit for secondary classes they passed using a verification form. The Ohio Department of Higher Education, which administers articulated credit programs, has an online credit transfer tool that enables students to look up equivalencies for coursework, credentials, and experience. Articulated credit shows up on a student’s college transcript but does not include a course grade.

The majority of dual-credit options focus almost exclusively on traditional academic courses. For many students, this traditional route fits their postsecondary and career plans. But for the thousands of high schoolers who are enrolled in CTE programs, traditional dual-credit options aren’t always as useful. That’s where Career-Technical Credit Transfer, a type of articulated credit, comes in. State law requires that the state Departments of Education and Workforce and Higher Education create a policy that allows students to transfer technical courses to state institutions of higher education. The departments have opted to fulfill this mandate in two ways: through bilateral articulation agreements and Career Technical Assurance Guides (CTAGs).

Bilateral articulation agreements are arrangements between a secondary CTE program and a higher education institution. In essence, they are written assurances that courses completed in a secondary CTE program will count for credit at a particular college or university offering a program in the same field. Colleges outside the agreement can also award credit, but they aren’t required to do so. This option is typically utilized by career tech centers, and can include local business partners as part of the agreement.

CTAGs, on the other hand, are statewide articulation agreements. This means that, by law, all public colleges and universities are required to award postsecondary credit for particular CTE courses. Not every CTE course is included in a CTAG, but there are a wide variety of program options, like virtual design and imaging or electrical engineering technology, that transfer to a wide range of institutions. The state requires students to meet standards—such as successfully completing the course and earning a qualifying score on the corresponding end-of-course exam—to receive credit via a CTAG. Students must seek credit within three years. The state also has Industry-Recognized Credential Transfer Assurance Guides, which guarantee that students will be awarded college credit for approved industry-recognized credentials.

Conclusion

Ohio has a vibrant and established CTE sector. Every high school student has access to CTE courses and programs, whether through their assigned CTPD or through College Credit Plus. These courses and programs offer students the opportunity to explore various career fields, participate in work-based learning, earn high school and college credit, obtain a high school diploma, and attain industry-recognized credentials that can lead to well-paying jobs or additional educational opportunities.

But there is still much work to be done to ensure that Ohio’s CTE sector is living up to its full potential. Far too many students and families are unaware of the plethora of opportunities that exist along with their short- and long-term benefits. And although a foundation for transparency and accountability is already in place, the state must do more to clearly and concisely track data on access and outcomes, and to ensure that courses, programs, credentials, and work-based learning opportunities are rigorous and meaningful.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my Fordham colleagues Michael J. Petrilli, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Chad L. Aldis, and Aaron Churchill, as well as Cassandra Palsgrove of Ohio Excels, for their thoughtful feedback during the drafting process. Jeff Murray assisted with report production and dissemination. Special thanks to Nathan Leibowitz who copy edited the manuscript and Andy Kittles who created the design.

- Jessica Poiner, Senior Education Policy Analyst, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Endnotes

[1] This paper does not delve into federal standards, accountability, or Ohio’s Perkins plan.

[2] In addition, the state has two correctional institutions that offer CTE programming.