Thanks to the leadership of Governor DeWine, Lieutenant Governor Husted, and the General Assembly, Ohio has recently made significant strides in narrowing the charter funding gap. One of the most critical initiatives is the Quality Community School Support Fund. Since FY 2020, this program has provided supplemental aid to quality charter schools—currently, in the amount of $3,000 per economically disadvantaged pupil ($2,250 per non-disadvantaged).

Our latest report is an evaluation of the high-quality charter funding program. It finds positive results: The additional dollars have allowed charters to boost their teachers’ salaries, reduced staffing turnover, and driven student learning gains.

Foreword

By Aaron Churchill and Chad L. Aldis

Under the bold leadership of Governor Mike DeWine and Lieutenant Governor Jon Husted, Ohio lawmakers enacted the Quality Community Schools Support Fund (QCSSF) in 2019. The program—the first of its kind in the nation—provides additional state dollars to support high-performing public charter schools (also known as “community schools” in Ohio). From FY20 to FY23, between 20 and 40 percent of Ohio’s 320-some charters met the state’s performance criteria and received an extra $980 to $1,600 per pupil, depending on the year. Though it’s too early to study its impacts, lawmakers in last year’s state budget further increased program funding starting in FY24.

QCSSF helps address longstanding funding gaps faced by Ohio charters, which have historically received about 30 percent less taxpayer support than nearby districts. This shortfall has exposed charters to poaching by better-funded districts that can attract teachers via superior pay. It has also limited charters’ capacity to provide extra supports for students, most of whom are economically disadvantaged and could use supplemental services such as tutoring. The gap has also required charters—even high-performers—to operate on a shoestring, leaving them little room in their budgets for expansion. Besides limiting these schools in practical ways, underfunding charter students’ educations by virtue of their choice of public school is simply unfair.

We at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute have proudly advocated for QCSSF. To be sure, even with the most recent boost in funding, it still doesn’t quite achieve the ambition of full funding equity for all charter students. But it does represent a big step forward. Given our support for the program, it might be surprising to see our interest in also evaluating it. Why put it under the research microscope and risk dinging it?

For starters, while you’ll often find us backing choice-friendly initiatives, we also seek programs that work for students. To that end, Fordham has commissioned studies that shed light on policies we broadly support (evaluations of private school scholarships and inter-district open enrollment being two examples). Sometimes the results are sobering—and have led us to pursue course corrections—and at other times, they’ve provided encouragement to press onward. In sum, we remain committed to rigorous analysis that helps policymakers and the public understand how education initiatives function and how they impact students.

We are also mindful that initiatives lacking follow-up research and solid evaluation are more susceptible to the chopping block. Consider one example. Back in 2013, Ohio lawmakers launched a brand-new, $300 million “Straight A” fund that aimed to spur innovative practices. The program was initially greeted with enthusiasm but just five years later it had vanished. One likely factor is that no one got under the hood to study the program, which allowed skeptics to more easily cast doubt on its efficacy. Without evidence to guide their decision-making, policymakers may well have assumed it wasn’t working and chose to pull the plug whether or not it was actually boosting achievement.

With this in mind, we sought to investigate—as soon as practically possible—whether QCSSF is achieving its aims. Conducted by Fordham senior research fellow and Ohio State University professor Stéphane Lavertu, this analysis examines the program’s impacts on qualifying charter schools’ staffing inputs and academic outcomes. The study focuses on data from 2021–22 and 2022–23—years three and four of program implementation—as the prior two years were disrupted by the pandemic. To provide the clearest possible look at the causal impacts of the extra dollars provided by QCSSF, Dr. Lavertu relies on a rigorous “regression discontinuity” statistical method that compares charters that narrowly qualified for QCSSF to charters that just missed meeting the performance-based criteria.

We learn two main things about the program:

- First, charter schools spent the supplemental funds in the classroom, most notably to boost teacher pay. As noted earlier, teacher salaries in charter schools have historically lagged. However, with the additional QCSSF dollars, qualifying charters were able to raise teacher pay by an impressive $8,276 per year on average. This allowed schools to retain more of their instructional staff, as indicated by a reduction in the number of first-year teachers as a percentage of their overall teaching staffs.

- Second, students attending qualifying schools made greater academic progress in math and reading than their counterparts attending non-QCSSF charters. Based on an analysis of the state’s value-added scores—a measure of pupil academic growth on state assessments—Dr. Lavertu’s most conservative estimates indicate that the supplemental dollars led to additional annual learning that is equivalent to twelve and fourteen extra days in math and reading, respectively. In addition to these achievement effects, he also finds that QCSSF reduced chronic absenteeism by 5.5 percentage points.

Various factors could have driven the academic results, including the ability to implement high-quality curricula or tutoring programs with the QCSSF dollars. But we suspect a particularly strong connection between the reduced teacher turnover and the positive outcomes. Provided that turnover is not caused by efforts to remove low-performing instructors, studies indicate that high levels of teacher turnover—something Ohio charters have struggled with because of their lower funding levels—hurts pupil achievement. The QCSSF dollars, however, have allowed charters to pay teachers more competitive wages and retain their talented instructional staff—thus helping to improve achievement.

Leaders of high-performing charters (including those sponsored by our sister organization, the Fordham Foundation) agree that the additional resources have proven pivotal. Andrew Boy, who leads the United Schools Network in Columbus, said, “Since the addition of the QCSSF, we’ve been able to vastly improve teacher pay to attract and retain more effective, experienced staff, which allowed us to serve more students and deliver on our mission.” Dave Taylor, superintendent of Dayton Early College Academy (DECA), said, “We have used these funds to address key strategic areas of focus: increasing teacher compensation, ensuring we have high quality instructional materials in all classrooms, and taking control of our students’ transportation. The QCSSF has truly been instrumental in DECA’s ability not only to weather the challenges of the pandemic but to be well positioned to serve students well long into the future.”

The findings from this report should encourage Ohio policymakers to keep pressing for improved charter funding. They should also ease concerns voiced by skeptics that charters would not put these additional dollars to good use (“obscene profits on the backs of students is the charter standard,” one bombastic critic said last year). Au contraire: The charters that qualified for the QCSSF program used the funds primarily to boost teacher pay, and the result was that students benefited. Isn’t that something we can all cheer?

Fordham remains committed to fair funding for charter students and to shining light on the QCSSF program. Indeed, we intend to come back in the next few years with updated evidence on the program. But for now, one can confidently say that the program has so far worked as intended and driven improvement in Ohio charter schools.

Executive Summary

Governor DeWine and the Ohio General Assembly established the Quality Community School Support Fund (QCSSF) in summer 2019. The program has since provided supplemental per-pupil funding to brick-and-mortar charter schools (called “community schools” in Ohio) deemed to be high quality and that primarily serve economically disadvantaged students. Most participating schools qualify based on a requirement that their students (1) have higher test scores than other students in the same district and (2) demonstrate greater test-score growth than the average student in the state. During the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years, 43 percent of brick-and-mortar charter schools qualified for and received an average payment of nearly $1,500 per pupil in supplemental funding.[1] The purpose of this study is to estimate the impact of these payments on eligible charter schools and their students.

The analysis employs a statistical method that enables one to assess the causal impact of public policies. Specifically, it employs a “regression discontinuity” (RD) design that compares the outcomes of schools that narrowly met QCSSF program requirements to the outcomes of schools that narrowly failed to meet those requirements. The RD design’s assumption, which this analysis tests, is that schools near the performance cutoff were nearly identical except that some went on to receive extra funding and others did not. The study’s reliance on school-level outcome data available for only two post-program years (2021–22 and 2022–23) limits its scope and the precision of the impact estimates. The RD method’s focus on charter schools near the program’s cutoff (schools with approximately average achievement among charters) also means the results may not generalize to all charter schools. Nevertheless, this study’s estimates are plausibly causal and the best evidence available of the QCSSF program’s effects.

The analysis indicates that charter schools receiving a QCSSF award in 2021–22 and 2022–23 spent the extra funds on classroom activities—notably on teachers—as opposed to administration or other nonclassroom functions such as transportation or food service. The main estimates indicate that schools receiving the extra funds had higher teacher salaries (by over $8,000), lower teacher turnover (by approximately 25 percent), and nearly four fewer students per teacher than they would have had without the extra funds. These budgetary and staffing impacts, in turn, correspond to more student learning in English language arts (ELA) and mathematics (lower-bound estimates indicate an additional two to three weeks’ worth of additional learning each year, though the main estimates are far larger) and lower rates of chronic absenteeism (by five to seven percentage points) relative to charter schools that narrowly missed qualifying for the program. Put differently, the results indicate that the funding enabled qualifying charter schools to substantially mitigate pandemic-era achievement and attendance declines among their primarily low-income students, as schools receiving QCSSF funding moved from approximately the fiftieth to the sixtieth percentile in the charter-school test-score and attendance-rate distributions.

This study’s estimates are imprecise and capture rough approximations. The strength of the research design, however, makes it reasonable to conclude that QCSSF funding led to increases in teacher pay—stabilizing charter schools’ teaching staff—and mitigated steep declines in student achievement and attendance. Indeed, this study’s most conservative estimates indicate that the returns of every dollar spent (as measured by student achievement growth) are justifiable, even setting aside benefits that might accrue from improved attendance and other behavioral outcomes. Generating precise estimates of spending efficiency requires more data, but this study indicates that, as of the 2022–23 school year, the QCSSF was likely an efficient use of state funds.

Quality Community School Support Fund

Governor Mike DeWine proposed the Quality Community School Support Fund (QCSSF) in the spring of 2019 as a part of his first state budget, and the Ohio General Assembly enacted the program later that summer. Under this initiative, qualifying brick-and-mortar (“site-based”) charter schools receive supplemental per-pupil funding if they meet the program’s academic performance standards. Between the 2019–20 and 2022–23 school years, which are the focus of this study, schools received up to $1,750 per economically disadvantaged student and up to $1,000 per noneconomically disadvantaged student, depending on the availability of funds. They were guaranteed at least three years of funding from the time they qualified, though subsequent Covid-related legislation provided schools funding through 2022–23 (a fourth year) if they first qualified for the award in 2019–20.[2] When the pandemic ended, additional schools became eligible for funding in 2022–23 based primarily on their academic performance in 2018–19 and 2021–22. QCSSF awards increased substantially starting in 2023–24, but most school data for that year are not yet available.

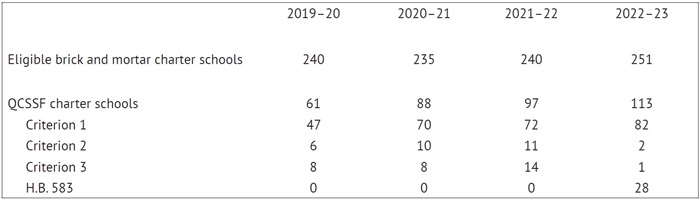

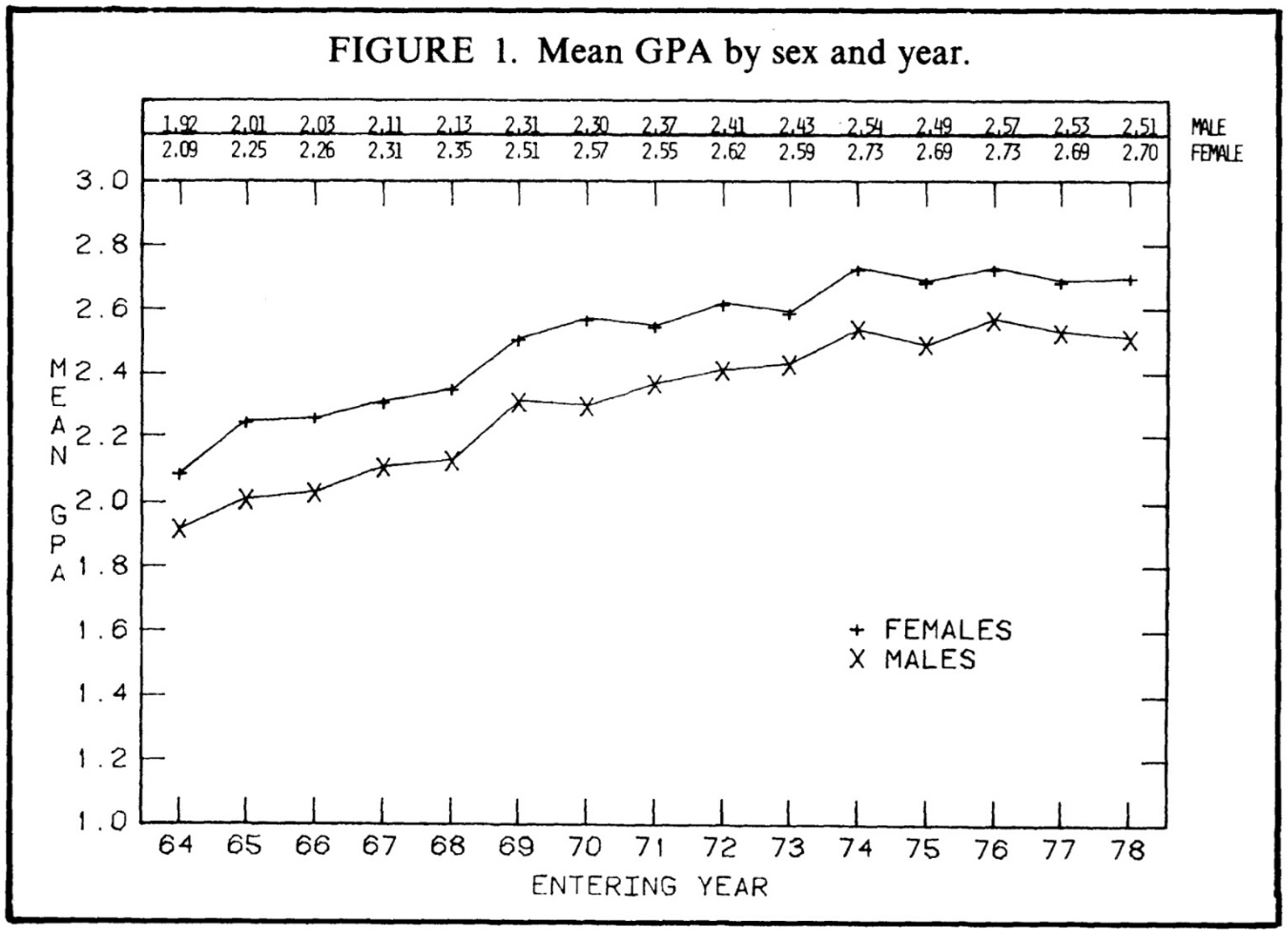

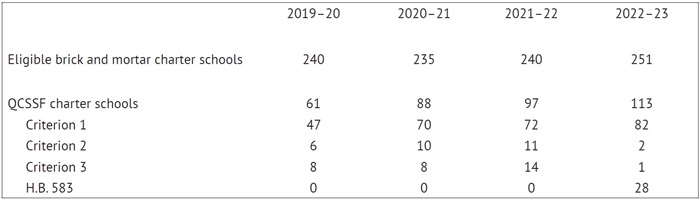

Table 1. Counts of schools that qualified[3] for QCSSF

Note. The table presents counts of all brick-and-mortar charter schools in Ohio, counts of brick-and-mortar charter schools that received a QCSSF award, and counts disaggregated according to the criterion through which they qualified for QCSSF.

Note. The table presents counts of all brick-and-mortar charter schools in Ohio, counts of brick-and-mortar charter schools that received a QCSSF award, and counts disaggregated according to the criterion through which they qualified for QCSSF.

Table 1 presents a breakdown of schools that received QCSSF awards. As the table indicates, the share of brick-and-mortar charter schools receiving QCSSF funding increased from 25 percent in 2019–20 (61 of 240 eligible schools) to 45 percent in 2022–23 (113 of 251 eligible schools). During that span, approximately 75 percent of schools initially qualified based on Criterion 1. This criterion requires that at least 50 percent of their students are economically disadvantaged, that their sponsors[4] were rated “exemplary” or “effective” in their most recent state evaluation, and that schools meet the following academic targets: (1) a higher “performance index” score than the district in which they are located, based on their two most recent report cards, and (2) a value-added rating of four or five stars (A or B in earlier years) based on their most recent report card.

This criterion requires that at least 50 percent of their students are economically disadvantaged, that their sponsors[4] were rated “exemplary” or “effective” in their most recent state evaluation, and that schools meet the following academic targets: (1) a higher “performance index” score than the district in which they are located, based on their two most recent report cards, and (2) a value-added rating of four or five stars (A or B in earlier years) based on their most recent report card.

New startup schools lacking a performance history also qualified if their sponsors were rated “effective” or “exemplary” and they were replicating a school model deemed effective (Criterion 2) or if they had received a grant from the federal Charter Schools Program or their operator had demonstrated effectiveness in another state (Criterion 3). Approximately 25 percent of schools initially qualified based on these criteria. Finally, House Bill 583 of the 134th General Assembly—in response to the pandemic—extended a fourth year of funding (in 2022–23 only) for schools that qualified for funding in 2019–20 and did not meet the academic criteria in subsequent years.

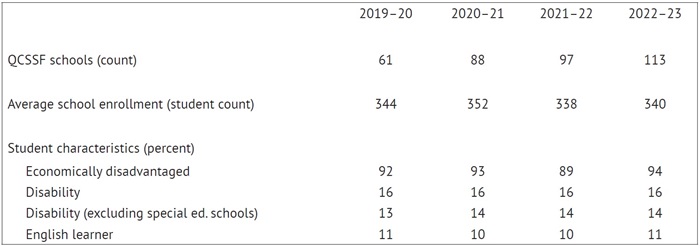

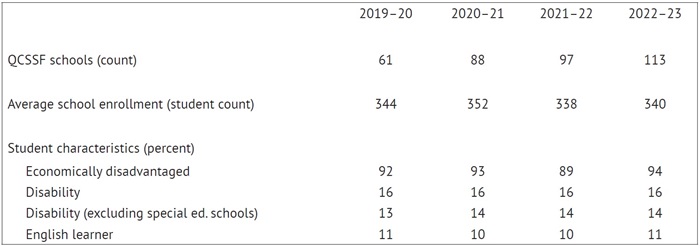

Schools that qualify for funding primarily serve students from low-income households in urban districts. As Table 2 indicates, as of 2022–23, the average charter school that received a QCSSF award had 340 students, 94 percent of whom were economically disadvantaged. Sixteen percent of students were also identified as having a disability (14 percent if one omits schools that primarily serve students with disabilities), and 11 percent were identified as English learners.

Table 2. Characteristics of schools that qualified for QCSSF awards

Note. The table presents information on students attending charter schools that qualified for QCSSF awards. Economically disadvantaged students are primarily those who qualify for free-/reduced-price lunch. Students with disabilities are those with individualized education plans. English learners are students whose native language is not English. The “disability” totals are also presented for a sample that excludes the three schools that primarily serve students with disabilities. The statistics understate the percentages of English learners and students with disabilities as missing values (unreported due to small cell sizes) are coded zero.

Note. The table presents information on students attending charter schools that qualified for QCSSF awards. Economically disadvantaged students are primarily those who qualify for free-/reduced-price lunch. Students with disabilities are those with individualized education plans. English learners are students whose native language is not English. The “disability” totals are also presented for a sample that excludes the three schools that primarily serve students with disabilities. The statistics understate the percentages of English learners and students with disabilities as missing values (unreported due to small cell sizes) are coded zero.

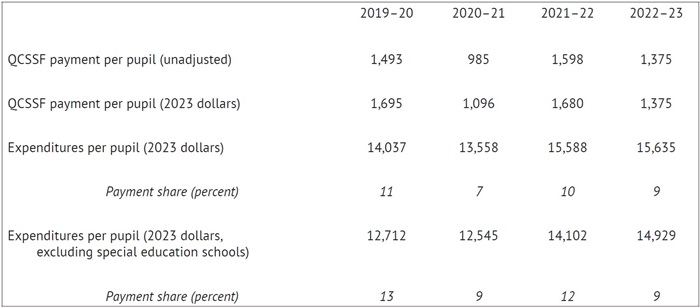

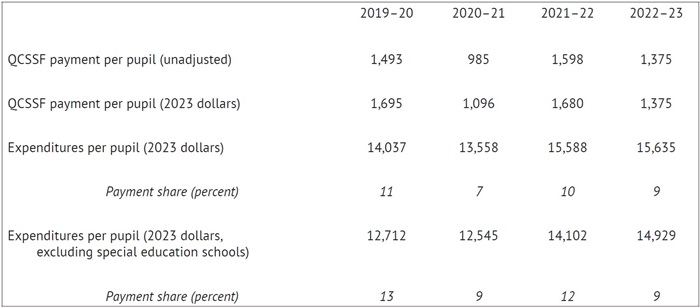

QCSSF awards depend on the availability of funds, which is based on the program appropriation in the state budget and the enrollments of schools that qualify. As Table 3 (below) reveals, average payments ranged from $985 per pupil for 2020–21 to $1,598 for 2021–22. Although inflation has negatively impacted the buying power of these payments, they still constitute a substantial share of awardees’ budgets. For example, the average payment of $1,375 in 2023 accounted for approximately 9 percent of the $15,635 in spending per pupil in the average school receiving an award (a total that includes temporary federal pandemic relief funds, nonoperating expenditures, and large supplemental funding in two special education schools that serve autistic children). That is down from 13 percent of total spending in 2019–20 but still accounts for a large share of total spending.

Table 3. School expenditures and QCSSF payments adjusted for inflation

Note. The table presents the average payments that schools received per pupil, both unadjusted and adjusted for inflation (2023 dollars), based on the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index. School expenditures include all school-level expenditures (both operating and nonoperating) and include federal pandemic relief funds and any other supplemental revenue, such as supplemental funds for special education schools serving autistic children.

Note. The table presents the average payments that schools received per pupil, both unadjusted and adjusted for inflation (2023 dollars), based on the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index. School expenditures include all school-level expenditures (both operating and nonoperating) and include federal pandemic relief funds and any other supplemental revenue, such as supplemental funds for special education schools serving autistic children.

Research on the impact of public school expenditures indicates that approximately $1,500 in supplemental funding should, on average, lead to test-score increases of approximately 0.05 of a standard deviation after four years.[5] Although that is a modest average effect, effect sizes vary significantly and depend on the interventions funded. Brick-and-mortar charter schools have been an unusually efficient educational option for Ohio students, and they primarily serve low-income students who stand to gain disproportionately from attending a high-quality school—particularly in the wake of the pandemic. Consequently, one might expect $1,500 in QCSSF funding to have larger achievement benefits than the modest 0.05 standard deviations found in the average study.

Although such increases in annual spending could have noteworthy effects on charter students’ academic performance, how the money is disbursed may prevent charter schools from fully realizing such gains. One reason is that awards are made during the latter half of the school year. For example, awards for the 2022–23 school year were made at the start of the 2023 calendar year. Thus, charters may not be able to make the best use of the money until their second or third years of funding. Additionally, charters receiving the award across all years, from 2019–20 through 2022–23, may have come to count on it. If they anticipated losing the award in 2023–24 due to lackluster performance or a reduction in the share of students who are economically disadvantaged, they might have set the extra money aside instead of spending it immediately. These possibilities could limit the impact of QCSSF awards as well as this study’s ability to detect that impact.

Study Design and Validity

This study evaluates the impact of QCSSF awards on the effectiveness of Ohio charter schools during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years—the first post-pandemic years for which necessary test-based outcome measures are available.[6] Specifically, the analysis estimates the causal impact of QCSSF awards on charter schools’ spending, staffing, and academic performance using publicly available data from the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (ODEW) website.[7] There are two primary challenges with estimating the causal impact of the program. First, by definition, the typical charter school receiving the award is different than the typical charter school not receiving it, making simple comparisons of their performance problematic. Second, using school-level data to examine changes in performance might make it appear as if QCSSF schools became more effective when, in fact, receiving the award merely enabled them to attract higher achieving students. This study’s design addresses both concerns.

The key to estimating the QCSSF program’s causal impact is to take advantage of the fact that awards are largely made based on schools meeting a strict performance cutoff (Criterion 1 discussed above). Schools very close to that performance cutoff should be nearly identical except that, by random chance, some find themselves above the performance requirement while others find themselves below it. If this testable assumption holds, one can use a “regression discontinuity” (RD) design to compare changes in the administration and performance of schools that find themselves just above or below QCSSF’s performance requirement. This design is widely considered among the strongest evaluation designs, provided that its assumptions and data requirements are met.[8]

To implement an RD design in this context, I first limit the sample to eligible charter schools with student bodies that were at least 50 percent economically disadvantaged and sponsors that were rated “exemplary” or “effective” according to their latest evaluation. I then identify how close schools were to meeting the performance requirements to receive funds in 2021–22 and 2022–23 based on Criterion 1.[9] Focusing on schools close to the performance threshold, I compare changes in their expenditures, staffing, and student outcomes (from 2018–19, just before the first award, to 2021–22 and 2022–23) between schools that did and did not qualify for the award based on Criterion 1.[10] Importantly, schools that narrowly qualified for an award were similar to those that narrowly failed to qualify as of 2018–19, just before the establishment of the QCSSF program.[11] Schools that narrowly failed to qualify for an award (based on their performance in 2018–19 or earlier) also were not statistically more likely to close prior to the 2022–23 school year than those that received the award.[12] These validity tests indicate that the RD design should provide credible estimates of the causal impact of awarding QCSSF funding to charter schools near the performance cutoff.

Because the analysis employs school-level data, it is important to also assess whether estimated effects are due to more learning or changes in student composition. Fortunately, qualifying for QCSSF funding appears to have no effect on the characteristics of schools’ students, such as total enrollments or the percent who are economically disadvantaged, have a documented disability, or have limited English proficiency.[13] Correspondingly, as the analysis below reveals, controlling for a school’s student characteristics does not change the estimates—it merely makes those estimates more precise (i.e., more statistically significant), which is what one would expect if the estimated impact of QCSSF funding is due to student-level improvements in achievement and attendance as opposed to changes in schools’ student composition. Moreover, the primary outcome in the analysis is school-level “value added” to student achievement, which is meant to isolate the impact of schools on student learning—holding constant students’ test scores from prior years. This measure should not be affected by school composition changes.[14] Unfortunately, no such value-added measures are available for school-level rates of absenteeism, and there is no way to estimate accumulated student-level test-score gains from 2018–19 to 2022–23 (across all four years of the QCSSF program). The value-added measures can only capture annual achievement growth that occurred during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years, respectively.[15]

The analysis provides further confidence in the RD design because the estimated impacts are generally insensitive to narrowing or expanding the sample of schools used in the analysis. Specifically, the estimated effects of QCSSF are similar in magnitude whether one limits the sample to schools within 0.3 standard deviations of the performance threshold (including only schools very close to the threshold) or expands the sample to schools within two standard deviations of the threshold (a bandwidth which includes all but one of the schools that qualify for a QCSSF award).[16] Similarly, the estimated effects are generally insensitive to the inclusion of statistical controls.[17] To maximize statistical power, however, this analysis focuses on statistical models that (1) control for the district in which schools are located; (2) control for up to three baseline values (from 2016–17, 2017–18, and 2018–19, respectively) of the applicable spending, staffing, or student outcome variable; and (3) employ large bandwidths (e.g., the results below are based on samples within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff).

The inclusion of pre-QCSSF control variables in the statistical models implies that the analysis is essentially comparing changes in school inputs and outcomes since 2018–19 between qualifying and nonqualifying charter schools located in the same school district. The use of relatively large bandwidths means that a large proportion of Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools are included in the estimation. It is important to keep in mind that, regardless of the size of the bandwidth used in the analysis, the RD design always involves estimating the impact of the program by comparing schools very close to the QCSSF performance cutoff. In other words, regardless of the number of schools included in the analysis, the procedure involves estimating differences between schools that narrowly qualified to those that narrowly failed to qualify. That the various bandwidths yield comparable estimated effects indicates that this is indeed the case.

Impact of QCSSF on Charter School Spending and Staffing

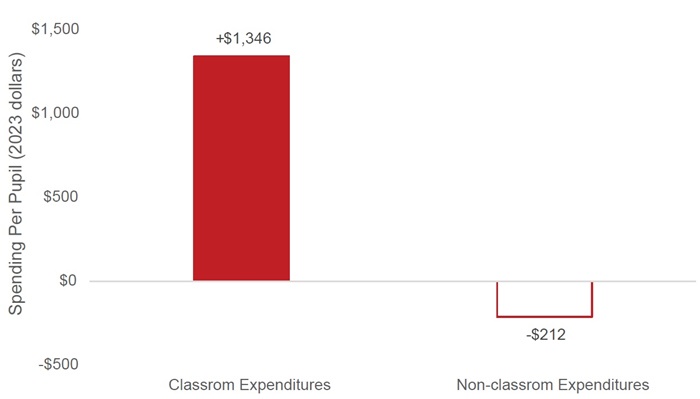

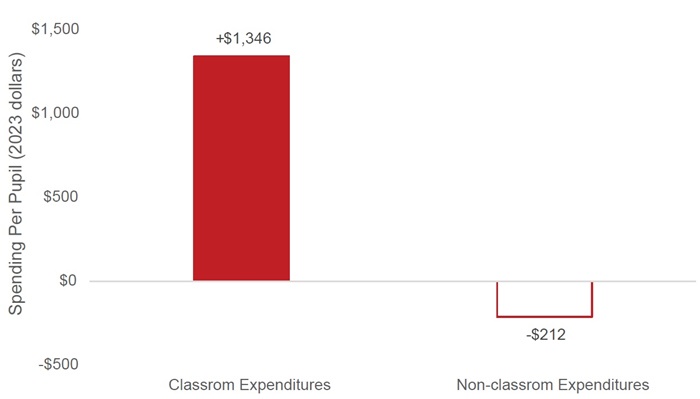

The following figures and tables report the estimated difference in inputs and outcomes between schools that narrowly qualified for QCSSF funding and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Specifically, they report the estimated impact based on models that employ a bandwidth of 1.5 standard deviations, as this bandwidth captures a midpoint among the three preferred bandwidths used in the analysis and the estimated coefficients based on this sample capture approximately the average effect sizes among the three samples.[18] First, Figure 1 (below) presents the estimated impact of receiving QCSSF funding in 2021–22 and 2022–23 on schools’ operating expenditures per pupil in those two years. Positive (negative) numbers indicate that schools that qualified spent more (less) per pupil during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years (all in 2023 dollars) than schools that failed to qualify. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a one-tailed test.[19]

Figure 1 indicates that a QCSSF award leads to an increase in classroom expenditures of approximately $1,346 per pupil. This category of expenditures includes instruction (activities involving the interaction of students and teachers or instructional aides) and pupil support services. The estimated impact on nonclassroom operational expenditures—such as school administration, transportation, and food service—is negative but does not approach statistical significance. Although the estimates are far too imprecise to rule out meaningful positive or negative changes in nonclassroom spending, the results clearly indicate that schools receiving QCSSF payments spent the money primarily on classroom activities. The estimates of classroom spending are also imprecise—indeed, the only claim one can make with confidence is that schools increased classroom spending in response to QCSSF awards. However, the close correspondence between the estimate in Figure 1 and actual payment amounts (reported in Table 2) provides some confidence that the analysis yields informative point estimates.

Figure 1. Impact of QCSSF award on charter schools’ spending per pupil

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in spending per pupil between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive (negative) numbers indicate that schools that qualified spent more (less) per pupil during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years (all in 2023 dollars). The estimates are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D7 of Appendix D.

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in spending per pupil between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive (negative) numbers indicate that schools that qualified spent more (less) per pupil during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years (all in 2023 dollars). The estimates are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D7 of Appendix D.

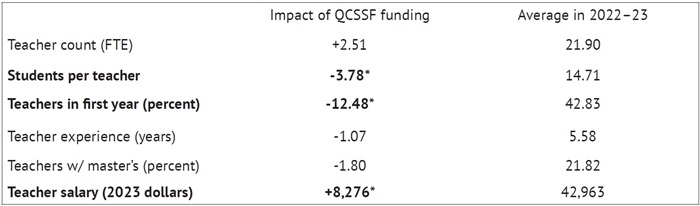

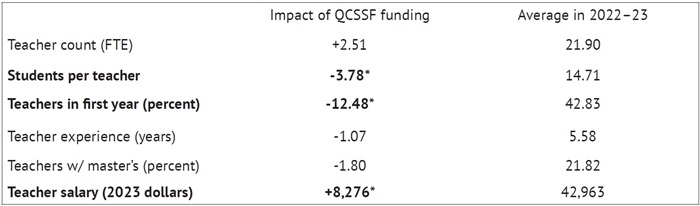

Classroom expenditures primarily go toward teacher-based instructional activities, so the next logical question is how this increase in funding affected teachers. Table 4 provides estimated impacts on teacher counts, salaries, and mobility (first column) and, for context, average values of those variables as of the 2022–23 school year (second column).[20] The results in the first row suggest an increase of approximately 2.5 teachers, on average, among schools that received a QCSSF award when compared to those that did not. Although that result is not statistically significant, that may have more to do with the imprecision of the statistical estimates. Indeed, the more precise estimate of QCSSF’s impact on student-teacher ratios attains statistical significance, hence the bolded text and star next to the estimate. Specifically, the result indicates that schools that received the funding had nearly four fewer students per teacher than those that did not. Because there were no significant enrollment declines in these schools, it appears this decline in student-teacher ratios is indeed due to QCSSF schools having more teachers.[21] Once again, the estimates are imprecise, but it is reasonable to conclude that QCSSF funding led to smaller student-teacher ratios and that this was likely because QCSSF-funded schools had more teachers as opposed to fewer students.

Table 4. Impact of QCSSF award on charter schools’ teachers

Note. The table presents the estimated impact of schools receiving a QCSSF award in 2021–22 and 2022–23 (column 1) and, for comparison, the characteristics of the average charter school’s teacher workforce in 2022–23 (column 2). The estimates are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. Estimates in bold and denoted with a star are those that attain statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D7 of Appendix D.

Note. The table presents the estimated impact of schools receiving a QCSSF award in 2021–22 and 2022–23 (column 1) and, for comparison, the characteristics of the average charter school’s teacher workforce in 2022–23 (column 2). The estimates are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. Estimates in bold and denoted with a star are those that attain statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D7 of Appendix D.

Charter operators have pointed to teacher turnover as one of the big challenges that charter schools face. Table 4 confirms this claim and suggests that receiving QCSSF funding went a long way toward addressing the problem. In the average charter school in the sample, approximately 43 percent of their teachers were new to the school during the 2022–23 school year. That means that, roughly, just under half of teachers turn over every year in charter schools.[22] However, the results indicate that the proportion of teachers new to QCSSF schools was 12.48 percentage points lower than it would have been in the absence of the program. That is a reduction in turnover of approximately 25 percent. Again, the models are imprecise, but the results provide clear evidence that teacher turnover declined.

How were charter schools with a QCSSF award better able to retain teachers? Table 4 indicates higher salaries might explain it. Schools that narrowly qualified for the award paid teachers approximately $8,000 more than schools that narrowly failed to qualify. Given the average charter school teacher salary during the 2022–23 school year was $42,963, the estimated salary increase associated with a QCSSF award is substantial. Table 4 also indicates that the extra classroom spending did not yield more experienced teachers or more teachers with a master’s degree. Salary increases may have enabled schools to retain more teachers, thereby enhancing the continuity of their teaching force from year to year. Because of tight labor markets in the wake of the pandemic, which made it difficult to recruit new teachers, the ability to retain teachers might also have contributed to smaller student-teacher ratios. If smaller student-teacher ratios had primarily come from hiring new teachers, then the percent of teachers in their first year would probably not have declined among schools receiving QCSSF funding.

The estimates are too imprecise to put too much weight on the exact numbers presented in Table 4. The models do not enable one to rule out effect sizes considerably below or above those estimates. What one can conclude with a reasonable level of certainty, however, is that QCSSF funding led to higher teacher salaries and lower teacher turnover.

Impact of QCSSF on Student Learning

Did higher teacher salaries, and a corresponding reduction in teacher turnover and student-teacher ratios, translate to improved student learning? To examine this question, the present analysis focuses primarily on the “value-added” measure of student achievement growth that Ohio makes available on school report cards. It enables one to assess whether student test scores are higher in schools that received additional funding, while holding constant students’ test scores in prior years. Also recall that, as of the 2018–19 school year, there were no differences in value-added between schools that narrowly did and did not qualify for funding (a key feature of the RD design) and that the analysis effectively estimates changes in value-added between 2018–19 (before the program) and 2021–22 and 2022–23. Thus, differences in test scores in 2021–22 and 2022–23 can plausibly be attributed to the QCSSF award improving student learning during each of those years, as opposed to those awards simply enabling schools to recruit higher achieving students.

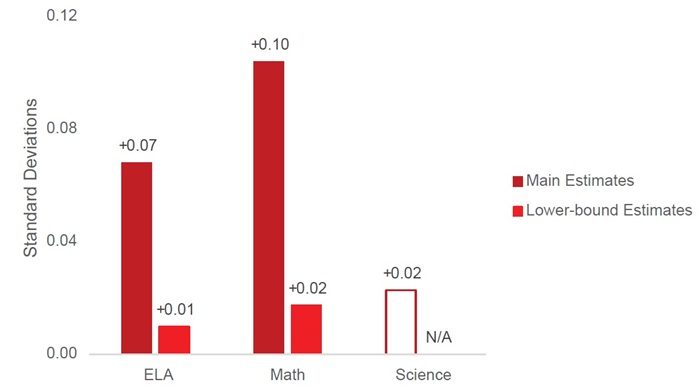

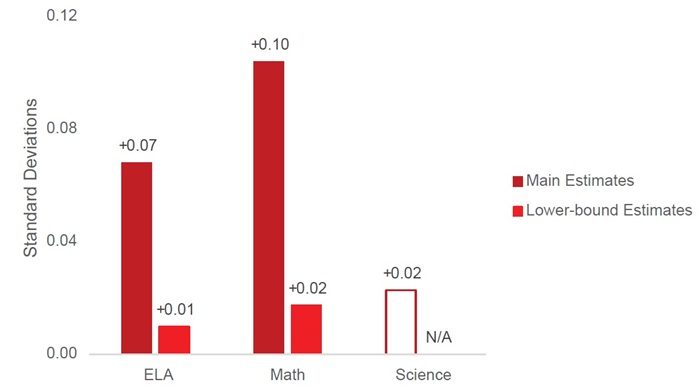

Figure 2 presents estimates of QCSSF awards’ impact on student learning by subject. Specifically, it presents value-added estimates for English language arts (combining results from Ohio state tests in grades 4–8 and the high school ELA I and ELA II exams), mathematics (combining state tests in grades 4–8 and high school Algebra I, geometry, Integrated Mathematics I, and Integrated Mathematics II), and science (combining state tests in grades 5 and 8 and the high school biology exam). Like the above estimates for spending and teachers, these “main estimates” average schools’ annual value-added (i.e., the amount of estimated learning for a given school year) for 2021–22 and 2022–23.[23]

Figure 2. Impact of QCSSF award on charter schools’ test-score value-added (all grades)

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in test-score value-added between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified learned more during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. The lower bound estimates are from the associated confidence interval. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 of Appendix D.

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in test-score value-added between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified learned more during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. The lower bound estimates are from the associated confidence interval. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 of Appendix D.

Figure 2 indicates that student learning in ELA and math was substantially greater in schools that narrowly attained the performance threshold for a QCSSF award, as compared to those that narrowly missed that threshold. The main estimates indicate that students in schools that received extra funding—and, consequently, had lower teacher turnover and student-teacher ratios—had test scores that were 0.07–0.10 of a standard deviation higher on their spring ELA and math tests (after controlling for their test scores in prior years) than students in schools that did not receive extra funding. These are substantial effects in ELA and math, though there is no significant impact in science.

Figure 2 also reports the most conservative estimates implied by the statistical models, as the amount of additional learning associated with QCSSF receipt is an important policy question. Specifically, it presents the lower-bound estimate from the statistical confidence interval around the main estimate. The results indicate that one can rule out, with a significant degree of statistical confidence, effects below 0.01 of a standard deviation for ELA and 0.02 of a standard deviation for math. Estimating a model using the average of ELA and math (which produces more precise results and, thus, a narrower confidence interval) yields a lower-bound estimate of 0.195 standard deviations. There is no lower-bound estimate for science because, as Figure 2 indicates with the empty bar, the estimated impact is not statistically different from 0.

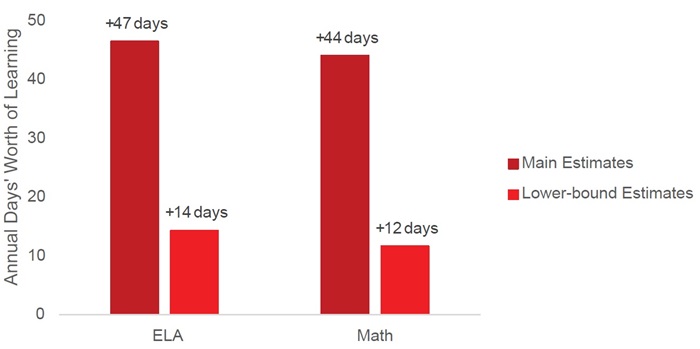

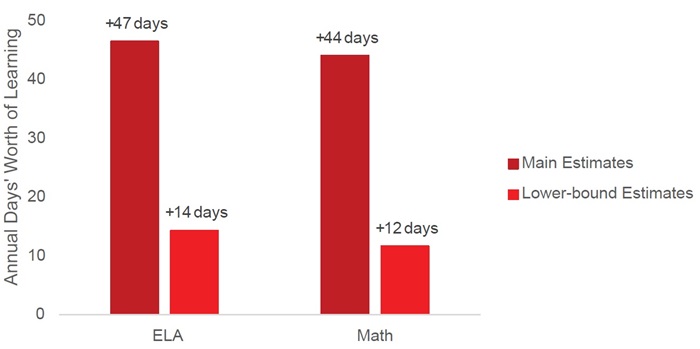

Figure 3 focuses on annual test-score value-added in grades 4–8 in ELA and math (thus excluding science and high school tests), as those estimates can be directly translated into a more intuitive metric: annual days’ worth of additional learning.[24] This metric is controversial and presents several potential problems.[25] Nevertheless, it provides at least some intuition for the effect sizes at hand, and it is commonly used in widely available reports of charter school effectiveness. Specifically, taking account of how much students typically learn every year (more in math than ELA) and assuming 180 days of instruction in the typical school year, the impact on test scores of increasing classroom expenditures by approximately $1,300 per pupil is the equivalent of students getting forty-four to forty-seven additional days of learning each year (2021–22 and 2022–23). If these annual gains accumulate as students progress from grades 4–8, then students who attended charter schools with extra funding for all of those years would have experienced over one full school year’s worth of additional learning by the time they get to high school.

Given the imprecision of the statistical models and the controversy surrounding “days of learning” conversions, however, using the lower-bound estimates may be more appropriate. Based on those estimates, those increases in classroom spending translate to twelve to fourteen days of additional learning—about 2.5 weeks of additional learning each year. In this case, accumulated gains through grade 8 would exceed over one third of a school year worth of learning. Concluding that achievement gains accumulate additively like this across years requires strong assumptions and is an issue addressed in the concluding discussion. What one can say based on these results, however, is that QCSSF awards had a large positive impact on student learning, even if one uses the most conservative estimates implied by this study.

Figure 3. Impact of QCSSF on charter schools’ annual test-score growth (grades 4–8 only)

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in test-score value-added between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive (negative) numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified learned more (less) during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are reported in days’ worth of additional learning annually for students in grades 4–8 and are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. The lower bound estimates are from the associated confidence interval. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 of Appendix D.

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in test-score value-added between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive (negative) numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified learned more (less) during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are reported in days’ worth of additional learning annually for students in grades 4–8 and are from models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. The lower bound estimates are from the associated confidence interval. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 of Appendix D.

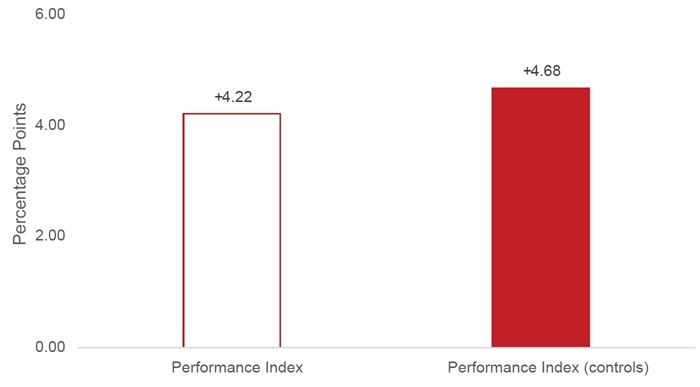

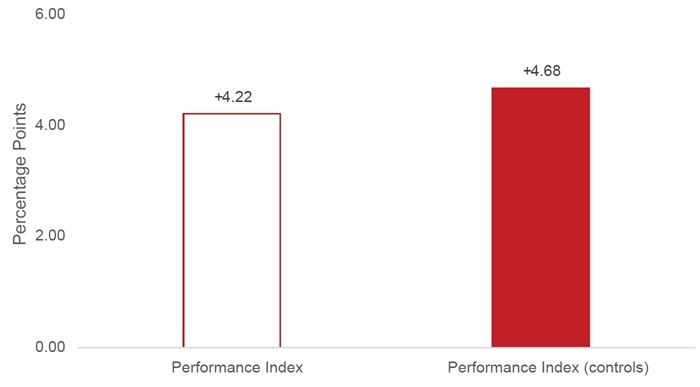

Another way to provide intuition for the achievement effects is to examine changes in schools’ performance index scores. The performance index does not control for changes in student composition like the value-added measure, but it could capture improvements in school quality if the characteristics of their students change little over time. Figure 4 (below) presents QCSSF impact estimates using the percentage of total possible points (0–100) a school received on the performance index.[26] The bar on the left indicates that schools that narrowly attained a QCSSF award had performance index scores 4.22 percentage points higher in 2021–22 and 2022–23 than those that narrowly missed receiving the award. This estimate does not quite attain conventional levels of statistical significance, but it corresponds to the value-added estimates above.[27] Importantly, the figure also reveals a similar estimate of 4.68 percentage points—one that does attain statistical significance—when the model controls for school enrollments and the characteristics of students in a school (percent economically disadvantaged, disabled, or limited English proficiency). That the inclusion of these controls increases statistical significance without meaningfully affecting the impact estimate suggests the performance index estimates indeed capture improvements in student learning.

How big are these effect sizes? The average brick-and-mortar charter school, like the average school that narrowly failed to qualify for QCSSF, had an average value of approximately 50 percent on the performance index in 2022–23. A relative improvement of approximately 4.5 percentage points (going from 50 percent to 54.5 percent) is equal to one third of the standard deviation in the performance index scores of Ohio charter schools. That is the equivalent of going from approximately the fiftieth percentile to the sixty-second percentile in terms of charter school educational quality.

Figure 4. Impact of QCSSF awards on charter schools’ average achievement

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in the performance index scores of charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified had higher index scores during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are reported in percentage points and are based on models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. The estimate on the right is based on a model that also controls for student counts and characteristics (percent economically disadvantaged, disabled, or limited English proficient) as of 2022–23. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 and Table D9 of Appendix D.

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in the performance index scores of charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Positive numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified had higher index scores during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are reported in percentage points and are based on models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. The estimate on the right is based on a model that also controls for student counts and characteristics (percent economically disadvantaged, disabled, or limited English proficient) as of 2022–23. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 and Table D9 of Appendix D.

Note that these results, like those in the rest of the analysis, capture average outcomes across the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. Total accumulated gains of the QCSSF program—which has funded schools as far back as 2019–20—are captured by the 2022–23 estimate because it is not weighed down by achievement in prior years, when achievement was still ramping up.[28] The 2022–23 impact estimate for the performance index is approximately seven percentage points or about half of the standard deviation in charter school performance. These results imply that, over the life of the QCSSF program since 2019–20, charter schools that narrowly qualified for supplemental funding improved relative to schools that narrowly failed to qualify such that they went from the fiftieth percentile to the sixty-ninth percentile in the charter school achievement distribution. In absolute terms, achievement in these schools indeed went down somewhat between 2018–19 and 2022–23, as the pandemic had an outsized impact on low-income students residing in urban areas.[29] What these results indicate is that QCSSF funding significantly limited the learning loss these schools otherwise would have experienced, leading them to climb the charter school performance distribution.

Impact of QCSSF on Student Attendance

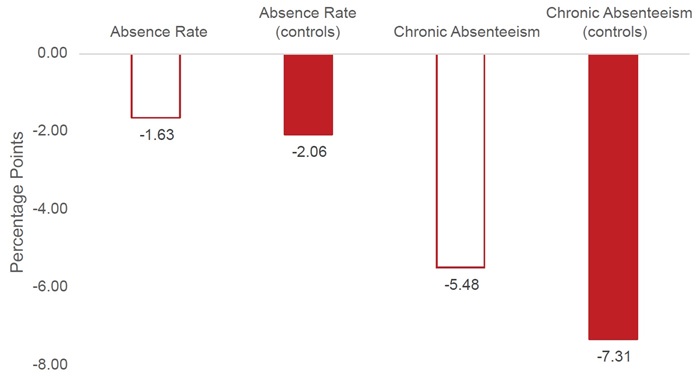

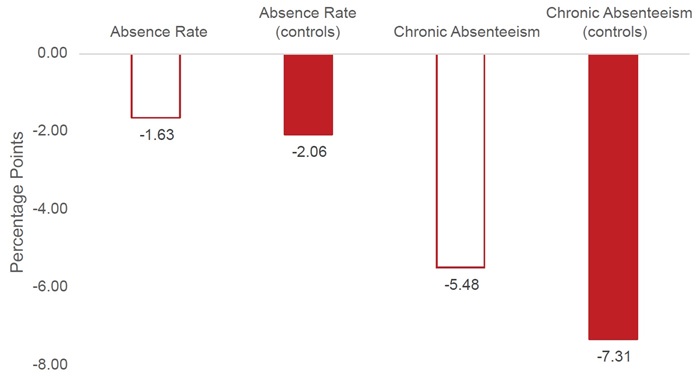

Attendance is both an input that leads to learning and an important educational outcome, as attendance rates capture behavioral attributes that are themselves predictive of better lifetime outcomes.[30] The analysis below examines differences in school absence rates (the percent of total instructional hours a school’s students missed) as well as rates of chronic absenteeism, which capture the percent of a school’s students who missed at least 10 percent of instructional hours (approximately eighteen days, or 3.5 weeks). As with the performance index, these school-level measures do not account for differences between students. Thus, once again, one must compare estimates with and without controls for student enrollments and characteristics.

Figure 5 (below) indicates that, on average, schools that narrowly qualified for QCSSF had lower absence rates (by 1.63 percentage points) and lower rates of chronic absenteeism (by 5.48 percentage points). These estimates are merely suggestive as they are not statistically significant. However, after controlling for student characteristics, estimates increase in magnitude and attain statistical significance. Holding constant the demographic characteristics of students as of the 2022–23 school year, QCSSF schools’ absence rates are 2.06 percentage points lower and their rates of chronic absenteeism are 7.31 percentage points lower than they would have been in the absence of the program. The average attendance rate in charter schools was 86 percent during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years, and the average rate of chronic absenteeism was 52 percent. The impact on attendance is equal to approximately one-third of a standard deviation in the charter school distribution, such that QCSSF funds enabled schools to improve from the fiftieth to the sixty-second percentile of the school attendance-rate distribution. Once again, it is important to note that attendance rates in fact declined significantly during the pandemic, even among schools that received supplemental funding. But schools with QCSSF funding ultimately realized more modest attendance declines than those without it, leading them to climb the charter school distribution.[31]

Unlike the analysis of student learning, the analysis of attendance is limited entirely to school-level measures that do not control for students’ academic histories. Thus, the analysis of attendance is less conclusive than the analysis of student achievement. However, that these estimates line up with the estimates for school value-added and performance index scores provides further evidence that the estimates capture schools’ positive impacts on student attendance.

Figure 5. Impact of QCSSF awards on charter schools’ absence rates

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in absence rates and rates of chronic absenteeism between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Negative numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified had lower rates during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are reported in percentage points and are based on models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. The estimate on the right is based on a model that also controls for student counts and characteristics (percent economically disadvantaged, disabled, or limited English proficient) as of 2022–23. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 and Table D9 of Appendix D.

Note. The figure presents the estimated difference in absence rates and rates of chronic absenteeism between charter schools that narrowly qualified for a QCSSF award and those that narrowly failed to qualify. Negative numbers indicate that students in schools that qualified had lower rates during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years. The estimates are reported in percentage points and are based on models that employ a sample of schools within 1.5 standard deviations of the QCSSF performance cutoff. The estimate on the right is based on a model that also controls for student counts and characteristics (percent economically disadvantaged, disabled, or limited English proficient) as of 2022–23. A solid bar indicates that an estimate attains statistical significance at the p<0.05 level for a single-tailed test. Full tabular results are available in Table D8 and Table D9 of Appendix D.

Summary and Implications

The analysis indicates that charter schools receiving a QCSSF award in 2021–22 and 2022–23 had higher classroom spending (+$1,346 per pupil), higher teacher salaries (+$8,276), nearly four fewer students per teacher, and less teacher turnover (by 12.5 percentage points, approximately 25 percent) than they would have had without the award. These budgetary and staffing impacts, in turn, correspond to more student learning in ELA and math (lower-bound estimates indicate an additional two to three weeks’ worth of additional learning each year) and lower rates of chronic absenteeism (by five to seven percentage points) than schools would have had in the absence of the program. The estimates are imprecise, but the analysis provides convincing evidence that QCSSF has enabled qualifying charter schools to substantially mitigate pandemic-era learning and attendance declines experienced across Ohio’s urban schools serving low-income students.

The QCSSF program’s impact is substantial. The effects on attendance are in line with what we might expect from the significant reduction in student-teacher ratios we observe.[32] The main achievement estimates, however, are more pronounced. They imply that an additional $1,000 in spending per pupil (the typical benchmark used in spending studies) yields gains in ELA and math achievement of approximately 0.05 standard deviations annually in 2021–22 and 2022–23, which suggests a cumulative impact of 0.1 standard deviations across those two years.[33] The value-added estimates are primarily driven by a large effect in 2022–23, which could be because students are rebounding from pandemic learning losses. Although realized in a single year of testing, these gains could conceivably have been facilitated by extra funding schools received and better student attendance every year since the program’s enactment in 2019. Nevertheless, even if the gains from the program are fully concentrated in 2022–23—such that the estimates in this study capture cumulative effects from all four years of funding since 2019–20—cumulative gains of 0.1 of a standard deviation after four years of additional spending are substantial. The average estimate in quasiexperimental studies implies that an increase in spending of $1,000 per pupil leads to achievement increases of approximately 0.032 of a standard deviation after four years.[34] In other words, increasing funding for Ohio charter schools has yielded three times the typical learning gains that come from increasing public school expenditures.

One reason for these large estimates could be statistical noise. As noted throughout the analysis, the estimates are imprecise. If one focuses on the lower-bound estimates—in other words, the minimum effect sizes one would likely get with statistical confidence—annual achievement gains associated with approximately $1,346 in funding are approximately 0.02 of a standard deviation in ELA and math, for a total of 0.04 standard deviations by the end of 2022–23. That implies an effect size of approximately 0.03 for every $1,000 dollar spent per pupil. If the gains from the QCSSF program were indeed primarily realized in 2021–22 and 2022–23, as the analysis of performance index scores suggests, then the average effect of the program is approximately 0.03 of a standard deviation after four years. That is just about the average effect of 0.032 that research indicates one should expect. Although this effect is modest in size, it captures a lower-bound estimate. This study suggests QCSSF’s impact on student learning was likely far greater.

There are several possibilities for the high returns to spending in Ohio charter schools that narrowly qualified for QCSSF awards, which are broadly similar to the typical brick-and-mortar charter school in Ohio. First, charter schools face stronger incentives than traditional public schools to direct resources toward student learning. Parents might not enroll their kids and sponsors might not renew their contracts if charter schools yield inadequate academic outcomes. Indeed, Ohio charter schools have long been more efficient than traditional public schools, in that they have realized superior achievement and attendance outcomes with far less funding.[35] Second, charter schools had been underfunded relative to district schools in Ohio, so the marginal returns to extra funding may be higher. Third, charter schools primarily serve low-income, low-achieving students who were hit exceptionally hard by the pandemic.[36] Research shows that the returns to spending are larger for low-income students,[37] and funding charter schools has long been a relatively efficient way to direct resources to students who need it most.

If additional funding has had such a large impact on charter school performance, then how is it that Ohio charter schools’ performance advantage over traditional public schools declined since the 2018–19 school year?[38] Part of the answer is that achievement growth in charters that narrowly qualified for the extra funding increased relative to the average achievement growth in Ohio, whereas students lost ground if they were in charters that narrowly missed out on the award.[39] That charter schools without extra funding struggled so mightily relative to schools with QCSSF funding—in terms of staffing and student outcomes—may be due to the unusually tight labor market in the wake of the pandemic. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds might have exacerbated this problem by enabling traditional public schools to go on a hiring binge,[40] which drove up salaries and perhaps made it even harder for most charter schools to attract and retain teachers than it was prior to the pandemic.[41] Whatever the precise cause, the results of this study suggest Ohio charter schools’ superior performance (relative to nearby district schools) could have been completely wiped out were it not for the QCSSF program making some charter schools more competitive in the teacher labor market.[42]

Increased student learning, as captured by test scores in ELA and math, should yield tangible benefits to Ohioans. Achievement on such tests is tied to better life outcomes for students and greater economic growth for states.[43] Back-of-the-envelope cost-benefit calculations based on the learning gains found in this study suggest that the economic returns exceed the costs of QCSSF through the 2022–23 school year.[44] There is also some emerging evidence that improved attendance rates and other behavioral outcomes can also yield their own down-stream benefits, beyond their contributions to student learning.[45] Overall, therefore, the results of this study suggest that QCSSF has been a worthwhile investment.

References

Abott, Carolyn, Vladimir Kogan, Stéphane Lavertu, and Zachary Peskowitz. “School district operational spending and student outcomes: Evidence from tax elections in seven states.” Journal of Public Economics 183 (2020): 104142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104142.

Baird, Matthew D., and John F. Pane. “Translating standardized effects of education programs into more interpretable metrics.” Educational Researcher 48, no. 4 (2019): 217–228, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19848729.

Calonico, Sebastian, Matias D. Cattaneo, and Rocio Titiunik. “Robust Nonparametric Confidence Intervals for Regression-Discontinuity Designs.” Econometrica 82, no. 6 (2014): 2295–326, https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11757.

Doty, Elena, Thomas J. Kane, Tyler Patterson, and Douglas O. Staiger. What do changes in state test scores imply for later life outcomes? (NBER Working Paper No. 30701). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30701

Gershenson, Seth. “Linking teacher quality, student attendance, and student achievement.” Education Finance and Policy 11, no. 2 (2016): 125–49. https://direct.mit.edu/edfp/article/11/2/125/10241/Linking-Teacher-Quality-Student-Attendance-and

Goldhaber, Dan, Grace Falken, and Roddy Theobald. “ESSER Funding and School System Jobs: Evidence from Job Posting Data.” Working Paper No. 297-0424, Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research, Arlington, VA, 2024. https://caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/CALDER%20WP%20297-0424.pdf.

Gottfried, Michael A., and Ethan L. Hutt, editors. Absent from School: Understanding and Addressing Student Absenteeism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2019. https://hep.gse.harvard.edu/9781682532775/absent-from-school/

Hanushek, Eric A., Jens Ruhose, and Ludger Woessmann. “Knowledge Capital and Aggregate Income Differences: Development Accounting for U.S. States.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9, no. 4 (2017): 184–224. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.20160255

Hill, Carolyn J., Howard S. Bloom, Alison Rebeck Black, and Mark W. Lipsey. “Empirical Benchmarks for Interpreting Effect Sizes in Research.” Child Development Perspectives 2, no. 3 (2008): 172–77. https://www.mdrc.org/work/publications/empirical-benchmarks-interpreting-effect-sizes-research

Jackson, C. Kirabo. “What do test scores miss? The importance of teacher effects on non–test score outcomes.” Journal of Political Economy 126, no. 5 (2018): 2072–107. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/699018

Jackson, C. Kirabo, and Claire L. Mackevicius. “What Impacts Can We Expect from School Spending Policy? Evidence from Evaluations in the United States.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16, no. 1 (2024): 412–46. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.20220279

Jackson, C. Kirabo, Shanette C. Porter, John Q. Easton, Alyssa Blanchard, and Sebastián Kiguel. “School Effects on Socioemotional Development, School-Based Arrests, and Educational Attainment.” American Economic Review: Insights 2, no. 4 (2020): 491–508. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aeri.20200029

Kogan, Vladimir. Student achievement and learning acceleration on Spring 2023 Ohio State Tests. Report to the Ohio Department of Education, 2023. https://glenn.osu.edu/research-and-impact/student-achievement-and-learningacceleration-ohio.

Kogan, Vladimir, and Stéphane Lavertu. How the COVID-19 pandemic affected student learning in Ohio: Analysis of Spring 2021 Ohio State Tests. Report prepared for the Ohio Department of Education, 2021. https://glenn.osu.edu/research-and-impact/how-covid-19-pandemic-affected-student-learning-ohio.

Lavertu, Stéphane. The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools on Student Outcomes, 2016–19. Columbus, Ohio: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2020. https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/research/impact-ohio-charter-schools-studentoutcomes-2016-19.

Lavertu, Stéphane. Ohio charter schools after the pandemic: Are their students still learning more than they would in district schools? Columbus, Ohio: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2024. https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/research/ohio-charter-schools-after-pandemic-are-their-students-still-learning-more-they-would.

Lavertu, Stéphane, and Long Tran. “For-profit milk in nonprofit cartons? The case of nonprofit charter schools subcontracting with for-profit education management organizations.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, early access. https://glenn.osu.edu/research-and-impact/profit-milk-nonprofit-cartons-case-nonprofit-charter-schools-subcontracting

Ohio Department of Education & American Institutes for Research. Ohio’s state tests in English language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies: 2018–2019 school year. Annual technical report, 2019.

Ohio Department of Education & Cambium Assessment, Inc. Ohio’s state tests in English language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies: 2021–2022 school year. Annual technical report, 2022.

Ohio Department of Education & Cambium Assessment, Inc. Ohio’s state tests in English language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies: 2022–2023 school year. Annual technical report, 2023.

Rose, Evan K., Jonathan T. Schellenberg, and Yotam Shem-Tov. “The effects of teacher quality on adult criminal justice contact.” Working Paper No. 30274, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2022. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30274.

SAS EVAAS. Statistical models and business rules. A report prepared for the Ohio Department of Education, 2023. https://ohiova.sas.com/support/EVAAS-OH-StatisticalModelsandBusinessRules.pdf.

Tran, Long, and Seth Gershenson. “Experimental estimates of the student attendance production function.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 43, no. 2 (2021): 183–99. https://ftp.iza.org/dp11911.pdf

Vosters, Kelly N., Cassandra M. Guarino, and Jeffrey M. Wooldridge. “Understanding and evaluating the SAS® EVAAS® Univariate Response Model (URM) for measuring teacher effectiveness.” Economics of Education Review 66 (2018): 191–205. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775718301341

Acknowledgments

I thank the Thomas B. Fordham Institute—particularly Chad Aldis, Aaron Churchill, Chester Finn, Amber Northern, and Mike Petrilli—for making this project possible and for offering their expertise and helpful feedback. I am also grateful to Cory Koedel for providing a thoughtful review and several helpful suggestions. Any remaining weaknesses in this study are entirely my fault.

- Stéphane Lavertu

Endnotes

[1] Brick-and-mortar charter schools focused on dropout prevention and recovery were not eligible for funding between 2019 and 2023 and are not included in these statistics.

[2] Schools can requalify for the program, and restart the three-year funding clock, if they meet the criteria again in subsequent years.

[3] Charter schools focused on dropout prevention and recovery are excluded from these totals because they were not eligible for funding from 2019–20 to 2022-23.

[4] In Ohio, charter authorizers—the entities that allow charter schools to open and to continue operating—are referred to as “sponsors.”

[5] See C. Kirabo Jackson and Claire L. Mackevicius, “What Impacts Can We Expect from School Spending Policy? Evidence from Evaluations in the United States,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16, no. 1 (2024): 412–46.

[6] The value-added achievement estimates needed for this study were unavailable for 2019–20 and 2020–21 due to the suspension of testing in spring 2020. The analysis pools two years of post-pandemic data (2021–22 and 2022–23) because some of the variables—particularly school spending and value-added—are very noisy due to dramatic shifts in student achievement and school funding. Pooling these years is not ideal because QCSSF awards for 2022–23 are based in part on 2021–22 school performance. However, one must include QCSSF selection based on 2021–22 school performance so that the statistical models are sufficiently predictive of QCSSF receipt and generate sufficiently precise statistical estimates. As the analysis below reveals, limiting the outcome analysis to 2022–23 actually increases the magnitude of the positive effects. Thus, pooling outcomes from 2021–22 and 2022–23 yields more conservative estimates while providing much needed statistical power.

[7] The “community school” annual report data enables one to identify the brick-and-mortar (“site-based”) schools that serve “general” or “special” education populations, which are the focus of this analysis. They also allow one to identify the school district in which charters are located. The teacher data used to conduct the salary and mobility analysis are available on ODEW’s data report portal. All other data are available on the data download page for Ohio’s school report cards.

[8] RD is a quasiexperimental research design that economists consider one of the “credibly causal” research designs, provided that its assumptions are tested and met. For example, in the Annual Review of Economics in 2022, Matias Cattaneo and Rocío Titiunik state, “RD design has become one of the most credible nonexperimental methods for causal inference and program evaluation.” If well implemented, studies using RD can meet the requirements of the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) “second tier” of evidence, just behind a well-implemented randomized controlled trial (RCT), which is the “gold standard” for estimating the causal effect of public programs and policies.

[9] Appendix B describes the procedure for creating the “running variable” that captures schools’ proximity to the QCSSF Criterion 1 performance threshold.

[10] Appendix C describes the statistical model I use to implement the RD design. The model estimates the change in probability of receiving an award based on being above or below the Criterion 1 cutoff, and it uses this change in probability to estimate the program’s impact on outcomes measured at the school level.

[11] Table D4 in Appendix D presents “balance tests” comparing the characteristics of schools at baseline. It reveals that, among the analytic sample (which employ bandwidths of 1, 1.5, and 2 points, respectively), there are three to five variables for which there is an imbalance as of 2018–19 that reaches or approaches conventional levels of statistical significance. These differences are primarily related to teacher degrees and years of experience and, correspondingly, classroom spending. Schools that just qualified for the program also had slightly lower performance index scores than those that narrowly failed to qualify. However, because this analysis examines changes in inputs and outcomes since 2018–19, these imbalances are not concerning for these particular variables (setting aside any validity concerns they present for this study’s design).

[12] Among schools in the sample (those with sufficient data), none closed if they received a QCSSF award. Nine schools closed that were eligible but did not meet Criterion 1. However, among schools near the QCSSF performance requirement, those that failed to receive an award were no more likely to close than those that received an award. See Table D11 in Appendix D for the results of the school closure analysis.

[13] See Table D10 in Appendix D for the results of the composition analysis.

[14] Appendix A describes how I created the value-added variables used in this analysis by modifying the publicly available school value-added data on ODEW’s report card data page.

[15] To capture total achievement gains between 2018–19 and 2022–23 using annual value-added measures, one would need to add up those annual gains in achievement for each of the intervening years. This is impossible because there are no valid value-added estimates available for 2019–20 and 2020–21. Thus, although comparing a school’s value-added between 2018–19 and 2022–23 (what this study does) is a good way to capture changes in school quality, it is not a good way to capture accumulated achievement gains from 2018–19 and 2022–23.

[16] Appendix C describes the procedure for selecting the bandwidths as well as the details of the statistical model. The “optimal” bandwidth generated using the procedure suggested by Calonico, Cattaneo, and Titiunik (2014) is generally between 0.3 and 0.7 standard deviations.

[17] The results of “reduced-form” models reported in Table D5 and Table D6 of Appendix D illustrate how the estimates are similar regardless of the bandwidth or inclusion of controls, though the primary models that account for location district “fixed effects” and baseline values of the outcomes yield results that are far more statistically precise. The main analysis of QCSSF’s impact (the “fuzzy RD” analysis reported in Table D7 and Table D8) uses the larger samples and full specifications to maximize statistical power.

[18] The tabular results appear in Table D7, Table D8, and Table D9 in Appendix D. The preferred analytic samples are based on bandwidths of 1, 1.5, and 2 standard deviations from the performance threshold for QCSSF funding. Estimates based on smaller bandwidths are not featured because those sample sizes are small and lead to underpowered models. Although the “optimal” bandwidth (in terms of balancing concerns for potential bias and precision) is generally between 0.3 and 0.7, estimates using those samples are too imprecise to detect expected effects (e.g., an increase of $1,500 in spending). Fortunately, as Table D5 and Table D6 of Appendix D illustrate, the coefficient estimates are broadly similar when using a bandwidth of 0.3 standard deviations.

[19] Whereas statistical significance in the appendix tables is based on two-tailed hypothesis tests, I focus on a one-tailed test in reporting these results because the impact of QCSSF funding arguably warrants a directional hypothesis. In other words, the expectation is that narrowly qualifying for the program, as opposed to narrowly failing to qualify, should lead to increases in expenditures.

[20] The 2022–23 average is based on the largest analytic sample within two standard deviations of the performance threshold.

[21] Table D10 in Appendix D indicates no significant changes in student composition, including enrollments.

[22] That is not exactly correct, as QCSSF schools may add teachers without losing existing teachers. However, a measure that focuses on the proportion of teachers no longer in the school (the proportion of teachers who, in the prior year, were in their last year) yields comparable results.

[23] These composites weight 2021–22 and 2022–23 equally, whereas the value-added estimates on the 2022–23 report card put twice as much weight on 2022–23. The estimates in this analysis are also scaled differently and, thus, are about half the size of the estimates one would get using the “effect size” measure from the report card. Appendix A provides a more thorough explanation of the value-added measure used in this analysis.

[24] Hill et al. (2007) find that students typically experience annual achievement gains of 0.314 of a standard deviation in reading and 0.422 of a standard deviation in math in grades 4–8. Dividing the estimates in Figure 2 by these typical growth rates yields a fraction of a school year, which one can multiply by 180 (the typical number of instructional days in a school year) to get annual days’ worth of additional learning.

[25] For example, see Matthew D. Baird and John F. Pane, “Translating standardized effects of education programs into more interpretable metrics,” Educational Researcher 48, no. 4 (2019): 217–28, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19848729.

[26] Although the performance index is calculated on a 0–120 scale, it is also reported on Ohio reported card data in percentage terms which facilitates interpretation and comparisons across schools and over time.

[27] As Table D8 and D9 of Appendix D indicate, the increase in the performance index is primarily in 2022–23 and the average effect when 2021–22 and 2022–23 are pooled is about half as large. These results parallel those from the value-added analysis. If school improvements had occurred in 2019–20 and 2020–21, the mean effect for the performance index would have been larger and would not have changed so significantly between 2021–22 and 2022–23.

[28] See the 2022–23 estimates in Tables D8 and D9 in Appendix D. All models in this study capture changes in outcomes since 2018–19 for schools that narrowly qualified and those that narrowly failed to qualify across the entire program history. Although value-added estimates are limited to learning that occurred within a given school year (2021–22 or 2022–23, which the analysis above averages together), the performance index captures a school-wide achievement level that can be compared between two points in time. Because the estimates for the performance index are insensitive to controlling for changes in student composition and the results line up with those of the value-added estimates, it is reasonable to conclude that student learning in QCSSF schools increased by approximately seven percentage points—about half of the standard deviation in charter school performance—over the life of the program.

[29] See Table D2 and D3 in the appendix to get a sense for trends among schools close to the QCSSF performance cutoff (within 0.3 points). This does not exactly capture schools at the cutoff, but it comes close.