Recent years have seen a flurry of new grading policies that risk lowering academic standards in the name of equity. Newly popular practices include “minimum grading” policies, which prevent teachers from assigning students less than 50 percent credit; prohibitions on grade penalties for late work; and bans on grading homework and class participation. Such changes in grading practices, which accelerated during the pandemic, deserve greater scrutiny. Indeed, they risk removing both discretion from teachers and crucial incentives for students to study hard and cooperate with teachers and peers. Although some grading reforms may benefit students, those that water down expectations ultimately harm the students they are meant to help.

Download the brief here or read below.

Executive Summary

This policy brief challenges four key ideas that underpin “equity”-motivated trends in grading reforms.

Claim 1: “The existence of grade inflation has been exaggerated.”

Maybe historically, but not now. While standards for assessing student work have been falling steadily over time, the “grading for equity” era appears to have supercharged grade inflation.

Claim 2: “Strict grading is harmful to students.”

False. To the contrary, lenient grading policies risk lowering expectations, and there is evidence that more lenient grading leads to less learning.

Claim 3. “Traditional grading doesn’t communicate what students know and can do.”

False. If accompanied by clear expectations, a traditional summary grade can indeed communicate what students know and what they don’t.

Claim 4: “Traditional grading perpetuates inequities.”

In some cases. Without efforts to increase transparency and reduce bias, traditional grading can perpetuate inequities.

The Bottom Line

The push for more “equitable” grading policies has exacerbated grade inflation and proffered little evidence of greater learning. Some aspects of traditional grading can indeed perpetuate inequities, but top-down policies that make grading more lenient are not the answer, especially as schools grapple with the academic and behavioral challenges of the postpandemic era.

Implications

1. Policymakers and educators should be wary of lowering standards through lenient grading policies. Those include “no-zero” mandates, bans on grading homework, and prohibitions on penalties for late work and cheating. Such policies tend to reduce expectations and accountability for students, hamstring teachers’ ability to manage their classrooms and motivate students, and confuse parents and other stakeholders who do not understand what grades have come to signify. All of this makes addressing recent learning loss even harder.

2. District leaders and state education agencies should support teachers in maintaining high expectations and holding the line on grade inflation. Educators need to know what high expectations look like. State and district leaders can present them with research on the connection between tough grading standards and student learning, as well as provide data about their grading standards relative to their peers. Individual schools or departments should often be allowed the flexibility to weigh the costs and benefits for themselves and to experiment with grading reforms—and individual teachers should have flexibility in adjusting deadlines or penalties based on student circumstances. What districts and states should not do is mandate reforms that could force teachers to lower standards and expectations. Such mandates are doomed to fail because so much depends on implementation, stakeholder buy-in, and the ways that reforms interact with other local policies.

3. Take the best parts from both traditional and equity-oriented grading approaches. Many traditional practices have persisted for good reason, but a few equity-motivated grading reforms should be adopted more widely. Specifically, there are good reasons for policymakers and educators to consider eliminating most extra credit assignments and implementing rigorous grading rubrics. These specific reforms do not lower academic standards, but they can strengthen academics and combat bias.

Background

In the 2000s and increasingly in the 2010s, the movement for “equitable” grading took root. Inspired by grading-reform gurus such as Ken O’Connor, Cornelius Minor, and Joe Feldman, a number of school districts—and at least one state—began implementing grading policies that explicitly or implicitly lowered expectations, including prohibiting teachers from assigning zeros (i.e., “minimum grading”), penalizing late work, and even marking down assignments on which students were caught cheating. Reformers have also argued for changing grading scales, which can have the effect of mechanically increasing students’ grades.

Then, in the face of widespread school shutdowns in the spring of 2020, districts scrambled to respond to students’ unprecedented needs. Amidst the context of racial reckoning, economic crisis, and a global pandemic, concerns about equity and mental health motivated many educators and policymakers to add on to or expand previous grading reforms, whether through pass/fail options, counting “needs improvement” as a final grade, prohibiting grade drops below prepandemic levels, or waiving standard graduation requirements.

The push to “give students grace” was understandable in that moment. Out-of-school inequities played a larger-than-ever role in students’ academic lives, with many students sharing devices with siblings, lacking quiet places to study, and struggling to access the internet to join class. Yet the return to traditional, in-person instruction did not bring a return to traditional grading policies. To the contrary, more districts than ever put into place grading policies that many district leaders believed were better for “equity,” or more precisely, leveling the playing field for disadvantaged students. Some of these policies—such as minimum grading (e.g., giving students no less than 50 percent of possible points) and prohibiting grading penalties for late work and even for cheating—make students’ grades rise automatically. Others seek alternatives to the traditional 0–100 scale, revising it to a 0–4 scale, for example, or to mastery grading (which is more qualitative than points based). Of course, not all equity grading reformers advocate all these practices, but these are all policies that, justified by a focus on equity, have gained substantial traction in recent years.

Such grading reforms were not birthed during Covid, but their increasing popularity and growing implementation by states and districts is new. Unfortunately, many of these policies lower academic standards and are likely to do long-term damage to the educational equity their advocates purport to advance.

“The existence of grade inflation has been exaggerated.” Maybe historically, but not now.

Concerns about whether grades accurately reflect student learning have been raised for decades. As far back as 1913, educational psychologist Guy Montrose Whipple questioned “the reliability of the marking system,” which he characterized as “an absolutely uncalibrated instrument.” Since then, grade inflation, by which teachers assign ever higher grades for the same level of academic work, has persisted.

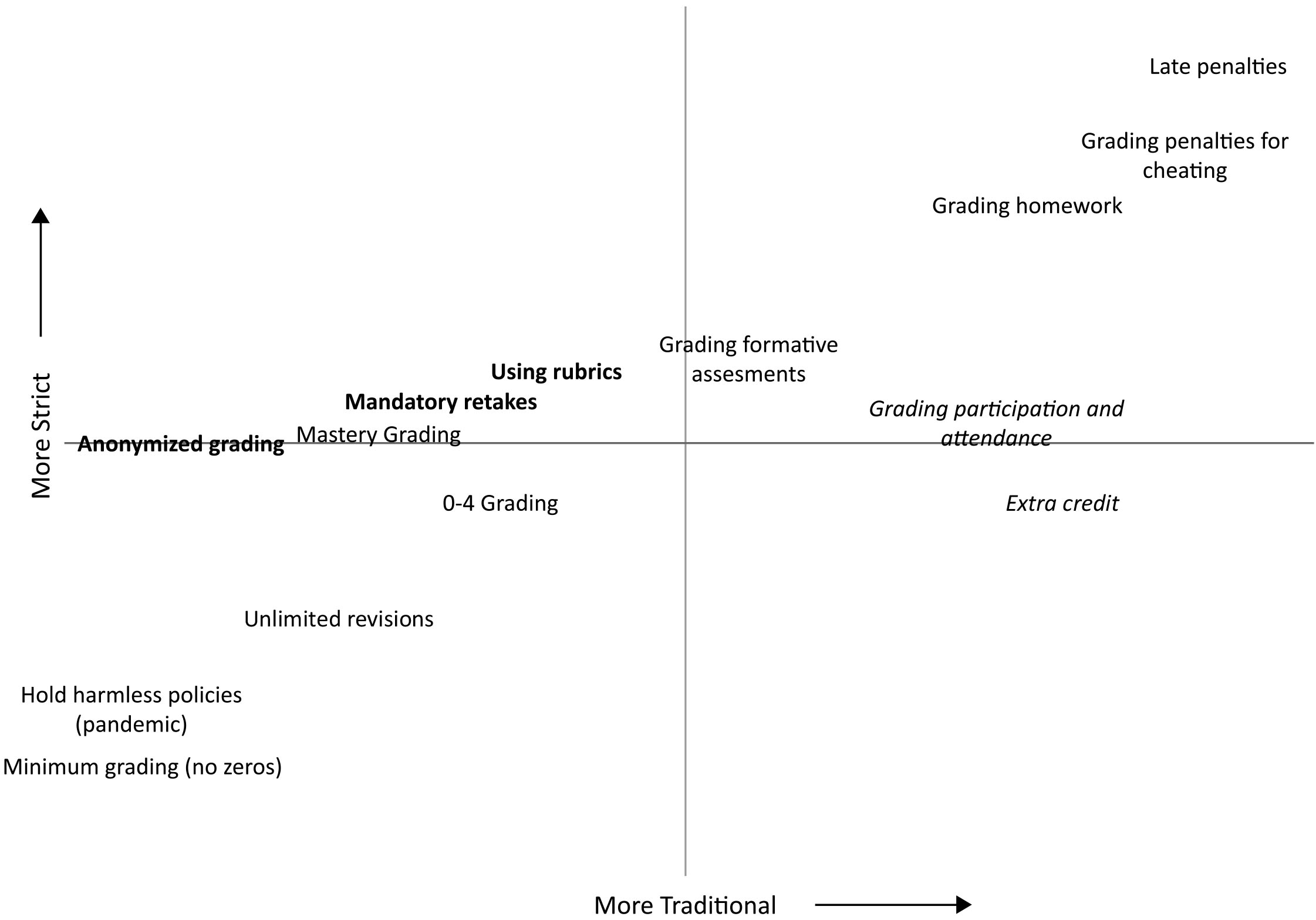

Yet in the last few years, grade inflation has not only accelerated but has become normalized and pervasive, reframed as a core battleground in the struggle for greater educational equity (Table 1). Although not all reforms lead to more lenient grading, many do (Figure 1).

Table 1: Equity-oriented grading policies

| Alternative Grading Scale | Mastery Grading | Grades are based on the extent of a student’s mastery of standards at the end of a course |

|---|---|---|

| 0–4 Grading | Grades are based on a scale of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, rather than a 100-point scale | |

| Lenient Grading | Minimum grading | Students must receive a minimum grade (typically 50 points on a 100-point scale), even for missing or incomplete work |

| No late penalties | Student grades for work submitted after a deadline may not be reduced | |

| Unlimited revisions | Students may resubmit work at any time without penalty | |

| No graded formative assessments | Only summative assessments that represent a student’s most up-to-date mastery of standards may be included in grades | |

| No graded homework | Homework may not be graded | |

| No grading penalties for cheating | Grades may not be reduced in cases of academic misconduct | |

| Hold-harmless policies (pandemic) | A student may not receive a final grade worse than the grade at a specific earlier point in the term | |

| Other | No extra credit | Students may not receive extra credit for optional tasks |

| No grading participation or attendance | Student grades may not be affected by participation and attendance | |

| Rubric-based grading | Assignments must be graded according to a transparent and specific set of criteria | |

| Anonymized grading | Student submissions are anonymized and/or graded by someone other than the student’s teacher | |

| Mandatory retakes | All students earning below a certain score on an assessment are required to retake it, instead of retakes being optional |

Figure 1. Although traditional grading tends to be strict, a few grading reforms may result in even stricter practices.

Note: This figure represents the authors’ subjective evaluation of the extent to which grading policies are traditional and/or strict. The upper-left quadrant shows reforms that tend to make grading stricter, while the lower-left quadrant shows reforms that tend to make grading more lenient. The upper-right quadrant shows traditional policies that tend to make grading stricter, while the lower-right quadrant shows a traditional policy that tends to make grading more lenient. Bolded policies are those that may help combat bias, and italicized policies are those that may contribute to bias. Descriptions of policies or reforms based on these policies are included in Table 1.

Feldman, who regularly consults with school districts and whose 2018 book Grading for Equity has become a staple of teacher professional development, contends that his proposed grading reforms actually counteract grade inflation, “particularly for more privileged students,” because “equitable grading no longer includes nonacademic, compliance-related, and subjectively interpreted behaviors.“ In discussing whether “classroom participation” should count, for example, Feldman worries that subjective grading practices will disproportionately inflate the grades of privileged students—who often benefit from advantages such as being more likely to encounter academic English at home.

Although this may be true in some cases, the claim that his recommended policies combat grade inflation ultimately confuses two aspects of grading: what should contribute to a course grade and how those activities should be assessed. After all, a teacher might grade class participation (the “what”), which Feldman claims may lead to grade inflation, but also use a rubric to do so strictly and fairly (the “how”). Meanwhile, another teacher might put more weight on an end-of-unit assessment (the “what”), which Feldman says will better capture a student’s mastery, but that assessment could be below grade level and scored based on subjective criteria (the “how”).

In the case of “no-zero” policies and prohibitions on marking down students, there is little possibility of counteracting grade inflation because grades inflate automatically. As explained below, mechanical grade inflation can also result from switching grading scales, for example going from a 0–100 scale to a 0–4 scale, because the same work is automatically assigned a higher grade.

Although it is difficult to quantify the impact of these specific grading reforms on national grading standards, pandemic-era grade inflation is well-documented and persistent. For example, a 2023 report from ACT showed that “the rate of grade inflation increas[ed] substantially during” the pandemic years. Not only was the average 2021 ACT composite score the worst of any year they reported (going back to 2010), but the average GPA of ACT test takers in that year was the highest ever recorded at 3.4 on a 4-point scale. In late 2023, studies in both Washington State and North Carolina also confirmed enduring disparities between student grades and test scores.

Although researchers assured us a decade ago that the “sky was not falling” when it came to grade inflation, ever more students are now winding up in the highest GPA range. And as colleges have relaxed or completely removed standardized testing requirements for admission, grades are more important than ever. So while standards for assessing student work have been falling steadily over time, the “grading for equity” era appears to have supercharged grade inflation.

“Strict grading harms students.” To the contrary, lenient grading leads to less learning.

The world of education is awash with rhetoric about the importance of holding “high expectations” for all students. What grading reformers have not understood is that high standards, rigorous grading, and student accountability are the incarnation of high expectations. Yet several of the core “equity grading” reforms—including not grading homework, allowing unlimited test retakes or assignment revisions, and prohibiting penalties for late work and cheating—weaken accountability for students. There’s ample research to support it, but the notion that students do better academically when they face some consequences—positive and negative—is common sense. Moreover, there is not an iota of hard evidence that reforms that make grading more lenient benefit students in the long run.

Rather, a growing literature on grading practices strongly suggests that students learn more when teachers hold them more strictly accountable for their performance in class. For example, a 2004 study by professors David Figlio and Maurice Lucas analyzed the academic performance of elementary school students based on their teachers’ grading practices. Those students assigned to teachers who graded more strictly—meaning that the teachers assigned relatively low grades to students while controlling for students’ test scores—went on to experience greater test-score growth in both reading and math. And in a similar 2020 study, American University’s Seth Gershenson found that high school students assigned to a tougher-grading teacher scored higher in math, both in that teacher’s class and in subsequent math courses, and that was true of all student subgroups.

The rationale behind rigorous teacher grading standards is straightforward: being exposed to a higher standard prompts many students to try harder, and this increased effort leads to more learning. In a study of college students, economist Phillip Babcock found that students who expected a “C” in their class studied about 50 percent more than students who expected an “A.”

Some promoters of more lenient grading encourage two practices that can contribute to grade inflation: the elimination of zeros for incomplete or missing work and the recalibration of numerical grading scales. Consider the adoption of the “0–4” grading scale as opposed to the traditional “0–100” grading scale. After the switch, students receive a 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 (meant to correspond to an F, D, C, B, or A). As with no-zero policies, the negative effect of low grades is reduced, because traditionally half or more of the 100-point scale corresponds to an F, whereas just 20 percent of the 0-4 scale does. Although teachers in different contexts frequently use alternative grading scales, including check marks, “satisfactory/unsatisfactory,” and variations of 100-point scales and letter grades, switching from a 100-point scale to a 0-4 scale typically means assigning higher grades for the same work, which is the definition of grade inflation.

A 2023 working paper used data from North Carolina to examine the effects on student attendance and test performance when the state recalibrated its grading scale in 2014. The range for A’s expanded from 93–100 to 90–100, while the range for F’s shrank from 0–69 to 0–59. In the year of this recalibration, high-performing students were awarded even higher grades (unsurprisingly, since the grading scale had lowered the numerical threshold for earning top letter grades). What happened to initially low-performing students, however, should give grading reformers pause: their grades failed to rise, while their attendance actually declined. This troubling finding provides further evidence that grade inflation can exacerbate inequities.

This type of grade inflation could be thought of as “points-based leniency,” where students are disincentivized to work hard. But another aspect of student accountability hindered by equity grading is “time leniency,” where students are disincentivized to complete work in a timely manner. Grading reformers often argue against grading interim work, including formative assessments and homework, or insist that students should be offered nearly unlimited time to complete revisions. For example, Feldman earnestly argues, “Students must fix their errors and give it another try until they succeed, which means we have to offer them that next try.” Unfortunately, the effect of reducing expectations for on-time work is to encourage procrastination, and this leniency on time surely has negative consequences for learning as well. One recent study, conducted as part of a master’s thesis, showed that when late penalties were lifted for assignments in a high school chemistry course, homework completion dropped by more than one-third.

Lowering expectations is bad public policy, as it reduces learning and undermines the capacity of schools to help students succeed in the long run. Truly excessive academic pressure can be harmful to students, but international studies have indicated that moderate levels of stress can actually lead to greater student motivation and achievement. What’s more, affluent students often have built-in mechanisms that hold them accountable, such as involved parents, as well as other resume boosters to distinguish themselves, such as AP courses and extracurricular activities. It is the students facing disadvantage who disproportionately rely on schools for motivation and credentials that can distinguish them academically. So-called “equity grading,” when it leads to more lenient grading, will often harm these students the most.

“Traditional grading doesn’t communicate what students know and can do.” False.

Advocates of grading reform argue that traditional grading obscures how students are actually performing in a class. First, they critique typical “omnibus” or “hodgepodge” weighted grading systems, wherein teachers calculate students’ scores in various categories—such as homework, tests, projects, and participation—and then weigh them to calculate an overall grade. Homework might be worth 10 percent of the final grade, tests worth 40 percent, and so on. As a result, a student who turns in all her homework and has average test scores may earn a final grade similar to that of a peer who missed some homework but earned superior test scores. Such a grading system, Feldman warns, “conceals critical information about students and leads to decisions that harm [students].” Parents and educators could over- or underestimate students’ level of content mastery, for instance, depending on how participation grades impact their averages.

Thus, some reformers call for grades to reflect only student mastery. If effort and behavior must be scored, the reasoning goes, those grades ought to be assigned separately, as has been policy for Boston Public Schools since 2023.

In fact, this practice is misguided. Modern online grade books already present students’ scores within different categories and provide parents access so that they can see, for instance, how their child performed on tests versus on homework. Most importantly, all final grades are—by definition—a summary of performance. Even if a school uses mastery grading, in which scores are based exclusively on demonstrated mastery of specific content or skills, the final overall grade will still reflect students’ mastery of the various categories of content being assessed. What’s more, having a single summary metric for communicating information can be helpful for a number of audiences: college admissions officers, for example, may not have the capacity to examine individual grades on five different categories for every single high school course.

Reformers’ greatest source of concern when it comes to grades and communication is that traditional grading partly reflects student behavior. That is, score penalties for behaviors like tardiness, cheating, and incomplete work produce grades that do not communicate information exclusively about students’ understanding of course content. A student who turns in an excellent paper late may, for example, receive the same grade as a student who turns in a decent paper on time.

Yet to many stakeholders, that is a desirable feature of grading, not a bug. After all, success in both college and career depends not only on academic abilities but also on soft skills (sometimes called “noncognitive” or “social and emotional” skills) that enable students to follow instructions, persevere, and cooperate with their peers. Down the line, college students receive serious consequences for cheating, including course failure, probation, and even expulsion. Employees cannot consistently submit late work or skip assignments without consequences. Ability and behavior go hand in hand in determining success, which is probably why course grade point average has historically been such a powerful predictor of later success.

Just as grade inflation diminishes standards and expectations, it also distorts signals about student performance. Whether about points or timelines, when grading is stricter, it can help educators identify students who need the most support, academic or otherwise. That is, regardless of whether students are struggling with content or with timely work submission, lower grades flag for teachers and administrators the students most in need of intervention; indeed, research confirms that GPA is a reliable predictor of dropping out. Being able to accurately identify at-risk students can therefore boost the effectiveness of preventative intervention programs.

Likewise, parents need to know when their children are falling behind. Between 2018–19 (the last prepandemic school year) and 2021–22 (the first postpandemic “in-person” year for most students), the average student lost about five months of learning in both reading and math, according to state tests. Yet, according to TNTP, most students “earned the same grade—or better—in 2022 as they did in 2019.” Putting the same trend into different terms, another study revealed that although under half of students are performing below grade level, almost 90 percent of parents believe their children are performing at or above grade level and two-thirds of parents rely on report cards as a primary indicator of their children’s academic progress. In the long term, stricter grading can also help guide students into best-fit college and career pursuits. That’s because grade inflation can lead students and parents to overestimate students’ knowledge and skills in a certain field; these false signals can contribute to poor choices of college major or career path.

When colleges cannot distinguish among applicants using measures like GPA, they make admissions decisions based on less objective and less equitable measures, such as extracurricular participation and teacher recommendations, which may communicate very little about students’ actual academic performance.

“Traditional grading perpetuates inequities.” In some cases.

Though many grading reforms result in lowered standards and expectations for students, that does not mean that all changes to traditional grading practices are inherently undesirable. Indeed, some reforms do not make grading more lenient, and others may hold students accountable even more effectively (see the upper-left quadrant of Figure 1, above).

First, grading reformers are right to call attention to the inequities perpetuated by teacher bias in grading. Biases around race, ethnicity, prior academic performance, physical attractiveness, student weight, and teacher perception of student organization and attendance can all affect grading decisions. As Feldman observes, it’s unfortunately not a realistic solution just to “stop our implicit biases,” which are deeply ingrained in individuals and our society.

Such biases are not just about outright prejudice. Classrooms often operate under an unspoken code. What constitutes successful “participation,” for instance? And even if that definition is clear, does it advantage students of certain personalities or language skills? What makes an essay a “B” paper, rather than an “A”-level exemplar or a still-passing “C” submission? Without clearly articulated answers to such questions, many students may face disadvantage, including those whose families have less experience in the U.S. education system and those who do not speak English fluently. A lack of transparency can thus be both discriminatory and an obstacle to learning.

That is why reforms that increase transparency around expectations and grading can be beneficial. Research confirms that scoring rubrics can reduce the effects of bias. Rubrics explicitly delineate the categories on which an assignment will be assessed; one category to be evaluated on an argumentative essay, for example, would be the thesis statement. The rubric should also lay out the criteria to earn a particular score in each category: an A-level thesis is clear, persuasive, and accurately synthesizes the paper’s argument; a B-level thesis is clear, persuasive, and partially synthesizes the paper’s argument; and so on, for each possible score and for each category.

As such, rubrics allow teachers to convey to students in advance of an assignment what the expectations are, as well as help teachers grade fairly and consistently, and they show students after the fact how they can improve (and where they have already been successful!). They can also help promote “interrater reliability,” so that teachers across the hall from each other aren’t assigning different grades for the same caliber of work. For a class discussion, for instance, a rubric can include categories such as the number of times a student participated and whether she cited class readings to support a claim, offered new ideas to the discussion, asked questions, or replied to a classmate’s remarks. In this way, rubrics establish clear expectations and a relatively objective—not to mention efficient—means of scoring students. A student’s discussion grade, therefore, really can reflect and communicate to others their mastery of discussion skills.

Other equity-centered reforms that deserve much greater attention are blind scoring (anonymized grading) and asking teachers to grade the work of students assigned to other teachers. If teachers do not know the identity of students, biased grading practices are less likely to seep through. Technology makes such approaches easier than ever, as grading platforms like Canvas offer anonymous grading options for teachers.

When it comes to what gets graded, equity-minded reformers get it right on some counts. Educators must be conscious of disparities in access to technology and quiet work spaces outside of school, and homework should not require parents’ help. However, inflexible no-homework policies throw the baby out with the bathwater; quality homework can offer important opportunities for independent practice, foster positive attitudes toward learning, and boost academic achievement. A truly equitable approach could also involve creating quiet spaces and times for students to complete homework within their school building.

As for what should not get graded, there are indeed good reasons to believe that extra credit should be eliminated in most cases. Although it is occasionally used as a way for advanced learners to attempt work that goes beyond the scope of the course, extra credit often involves assigning points for optional activities that only loosely pertain to the course, abetting not only grade inflation but miscommunication of students’ abilities and behavior. Instead, students who deserve an opportunity to earn more credit should have the opportunity to reattempt the assignments already given.

Grading reformers are also right to point out that grading “behaviors” can sometimes disadvantage the most marginalized students, communicating their personal obstacles more than their knowledge and skills. Late submissions may happen, for example, because a student is overwhelmed by family responsibilities, lacks a quiet space for homework, or is experiencing homelessness. But the top-down elimination of the expectation that students do their work on time is the opposite of equity. Instead, teachers should be able to exercise discretion over extensions, retakes, and the like—to provide each student with what is appropriate and needed.

As with monetary inflation, the point of combatting grade inflation is not to return to a golden age when a dollar could purchase a bushel of apples or an A was only assigned for truly remarkable academic achievement. The important thing is to hold the line. While the traditional 0–100 grading scale does not by itself uphold high expectations and academic rigor, adopting a more lenient grading scale is guaranteed not to do so. In the North Carolina study, for instance, the reform was simply to lower the numerical thresholds to obtain better letter grades, which in turn lowered standards and expectations. But there is no inherent reason that mastery grading or scales other than 0–100 cannot maintain or even enhance both rigor and transparency, when implemented conscientiously.

Above all else, grading reforms should not be mandated from the state or district down to classrooms. Individual schools, departments, and teachers should have the discretion to implement their own grading policies, depending on their school contexts and students’ needs. Equally important, administrators need to provide examples of and supports for rigorous and transparent evaluation of student work so that teachers can hold the line on grades.

Policy Implications

1. Policymakers and educators should be wary of lowering standards through lenient grading policies. Those include “no-zero” mandates, bans on grading homework, and prohibitions on penalties for late work and cheating. Such policies tend to reduce expectations and accountability for students, hamstring teachers’ ability to manage their classrooms and to motivate students, and confuse parents and other stakeholders who do not understand what grades have come to signify. All of this makes addressing recent learning loss even harder.

2. District leaders and state education agencies should support teachers in maintaining high expectations and holding the line on grade inflation. Educators need to know what high expectations look like. State and district leaders can present them with research on the connection between tough grading standards and student learning, as well as provide data about their grading standards relative to their peers. Individual schools or departments should often be allowed the flexibility to weigh the costs and benefits for themselves and to experiment with grading reforms—and individual teachers should have flexibility in adjusting deadlines or penalties based on student circumstances. What districts and states should not do is mandate reforms that could force teachers to lower standards and expectations. Such mandates are doomed to fail because so much depends on implementation, stakeholder buy-in, and the ways that reforms interact with other local policies.

3. Take the best parts from both traditional and equity-oriented grading approaches. Many traditional practices have persisted for good reason, but a few equity-motivated grading reforms should be adopted more widely. Specifically, there are good reasons for policymakers and educators to consider eliminating most extra-credit assignments and implementing rigorous rubrics. These specific reforms do not lower academic standards, but they can strengthen academics and combat bias.

References

Babcock, Philip. “Real Costs of Nominal Grade Inflation? New Evidence from Student Course Evaluations.” Economic Inquiry 48, no. 4 (October 2010): 983–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2009.00245.x.

Bazzaz, Dahlia, and Katherine Long. “Seattle Will Give High-School Students A’s or Incompletes; Colleges Urged to Adopt Generous Grading.” The Seattle Times, April 20, 2020. https://www.seattletimes.com/education-lab/seattle-will-give-high-school-students-as-or-incompletes-colleges-urged-to-adopt-generous-grading.

Boston Public Schools. “Student-Centered Equitable Grading Policy Update.” February 15, 2023. https://www.bostonpublicschools.org/cms/lib/MA01906464/Centricity/Domain/162/

Final%20Grading%20Policy%20Update%20PPT%20February%202023.pdf.

Bowden, A. Brooks, Viviana Rodriguez, and Zach Weingarten. “The Unintended Consequences of Academic Leniency.” Working paper, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, September 21, 2023. https://www.edworkingpapers.com/index.php/ai23-836.

Bowers, Alex J., and Ryan Sprott. “Examining the Multiple Trajectories Associated with Dropping Out of High School: A Growth Mixture Model Analysis.” The Journal of Educational Research 105, no. 3 (April 1, 2012): 176–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2011.552075.

Carifio, James, and Theodore Carey. “Do Minimum Grading Practices Lower Standards and Produce Social Promotions?” Educational HORIZONS, Summer 2010, 219–30. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ895689.pdf.

Castro, Marina, Linda Choi, Joel Knudson, and Jennifer O’Day. “Grading Policy in the Time of COVID-19: Considerations and Implications for Equity.” Policy Brief, California Collaborative on District Reform, April 2020. https://cacollaborative.org/publication/grading.

Chingos, Matthew M. “What Matters Most for College Completion?” Washington, D.C.: AEI, 2018. https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/What-Matters-Most-for-College-Completion.pdf.

Clark, Chrissy. “Portland Schools May End Grade Penalties for Cheating.” Daily Caller, September 7, 2023. https://dailycaller.com/2023/09/07/reaction-portland-grade-penalizations-cheating.

Heckman Equation. “Cognitive Skills Are Not Enough.” Chicago: Heckman Equation, 2010. Video. https://heckmanequation.org/resource/cognitive-skills-are-not-enough.

Cross, Lawrence H., and Robert B. Frary. “Hodgepodge Grading: Endorsed by Students and Teachers Alike.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council on Measurement in Education, New York, April 1996. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED398262.

Daviscourt, Katie. “Portland Public Schools no longer allowed to issue ‘zeroes’ for cheating or missing work under new ‘equity’ grading guidance.” The Post Millennial, August 29, 2023. https://thepostmillennial.com/portland-public-schools-no-longer-allowed-to-issue-zeroes-for-cheating-or-missing-work-under-new-equity-grading-guidance.

Diamond, David M. “Cognitive, Endocrine and Mechanistic Perspectives on Non-Linear Relationships Between Arousal and Brain Function.” Nonlinearity in Biology, Toxicology and Medicine 3, no. 1 (January 2005): 1–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2657838.

Dian, Mona, and Moris Triventi. “The Weight of School Grades: Evidence of Biased Teachers’ Evaluations against Overweight Students in Germany.” PLOS ONE 16, no. 2 (February 8, 2021): e0245972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245972.

EdNavigator, Learning Heroes, and TNTP. False Signals: How Pandemic-Era Grades Mislead Families and Threaten Student Learning.” Report. EdNavigator, Learning Heroes, and TNTP, 2023. https://tntp.org/publications/view/student-experiences/false-signals.

Feldman, Joe. Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press, 2018.

Feldman, Joe. Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press, 2018. p. 143

Figlio, David N., and Maurice E. Lucas. “Do High Grading Standards Affect Student Performance?” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9 (August 1, 2004): 1815–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00039-2.

Galloway, Mollie, Jerusha Conner, and Denise Pope. “Nonacademic Effects of Homework in Privileged, High-Performing High Schools.” The Journal of Experimental Education 81, no. 4 (July 15, 2013): 490–510. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1024833.

Gallup and Learning Heroes. B-flation: How Good Grades Can Sideline Parents. Report. Gallup and Learning Heroes, 2023. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/513881/parents-perspectives-on-grades.aspx.

Gao, Niu. Does Raising High School Graduation Requirements Improve Student Outcomes? Report. San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California, February 2021. https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/does-raising-high-school-graduation-requirements-improve-student-outcomes-february-2021.pdf.

Gerritson, Michael. “Rubrics as a Mitigating Instrument for Bias in the Grading of Student Writing.” Ed.D. diss., Walden University, 2013. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED554296.

Gershenson, Seth. Great Expectations: The Impact of Rigorous Grading Practices on Student Achievement. Report. Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, February 4, 2020. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/great-expectations-impact-rigorous-grading-practices-student-achievement.

Glock, Sabine, and Claudia Schuchart. “Stereotypes about Overweight Students and Their Impact on Grading among Physical Education Teachers.” Social Psychology of Education 24, no. 5 (October 2021): 1193–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09649-4.

Goldhaber, Dan, and Maia Goodman Young. “Course Grades as a Signal of Student Achievement: Evidence on Grade Inflation Before and After COVID-19.” CALDER Research Brief, no. 35. Arlington, VA: Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research, American Institutes for Research, November 2023. https://caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/CALDER%20Brief%2035-1123.pdf.

Goodwin, Bryan. “Research Says: Grade Inflation: Killing with Kindness?” Educational Leadership 69 (November 1, 2011): 80–81. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/grade-inflation-killing-with-kindness.

Grading for Equity. “Bring GFE to Your PLC, School, Or District.” 2023. https://gradingforequity.org/products-services/bring-equitable-grading-to-your-plc-school-or-district-2.

Grading for Equity. “Grading for Equity Virtual Summer Institute.” 2023. https://gradingforequity.org/products-services/grading-for-equity-virtual-institute-2.

Grose, Jessica. “Snowplow Parents Are Ruining Online Grading.” New York Times, November 29, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/29/opinion/grades-parents-students-teachers.html.

Grose, Jessica. “Teachers Can’t Hold Students Accountable. It’s Making the Job Miserable.” The New York Times, October 4, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/04/opinion/teachers-grades-students-parents.html.

Guskey, Thomas. “The Case Against Percentage Grades.” Educational Leadership 71, no. 1 (September 2013): 68–72. https://tguskey.com/wp-content/uploads/Grading-2-The-Case-Against-Percentage-Grades.pdf.

Hammond, Betsy. “Missing homework, late assignments matter little as Oregon schools grade exclusively on academic mastery.” Oregon Live, September 7, 2013. https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2013/09/missing_homework_late_assignme.

html.

Hess, Rick. “To Replace Skill Mastery for Seat Time, There Are 3 Requirements.” Education Week, January 8, 2024. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-to-replace-skill-mastery-for-seat-time-there-are-3-requirements/2024/01.

Hobbs, Tawnell D. “Down With Homework, Say U.S. School Districts.” Wall Street Journal, December 12, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/no-homework-its-the-new-thing-in-u-s-schools-11544610600.

Instructure Community. “How Do I Add an Assignment That Includes Anonymous Grading?” July 20, 2020. https://community.canvaslms.com/t5/Instructor-Guide/How-do-I-add-an-assignment-that-includes-anonymous-grading/ta-p/769.

Kennewell, Eliza, Rachel G. Curtis, Carol Maher, Samuel Luddy, and Rosa Virgara. “The relationships between school children’s wellbeing, socio-economic disadvantage and after-school activities: a cross-sectional study.” BMC Pediatrics 22, no. 297 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03322-1.

Laguarda, Ignacio. “Westhill High’s Trying a New Way to Grade Students to Make It More Equitable. Here’s How It Works.” Stamford Advocate, June 1, 2021. https://www.stamfordadvocate.com/news/article/Westhill-High-s-trying-a-new-way-to-grade-16216741.php.

Lemov, Doug. “Your Neighborhood School Is a National Security Risk.” Education Next 24, no. 1 (October 24, 2023). https://www.educationnext.org/your-neighborhood-school-national-security-risk-student-achievement-merit-losing-prospects-era-everybody-wins/.

Lichtman-Sadot, Shirlee. “Improving Academic Performance through Conditional Benefits: Open/Closed Campus Policies in High School and Student Outcomes.” Economics of Education Review 54 (October 2016): 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.07.001.

Ma, Ziye. “The Study on the Influence of Academic Pressure on Academic Performance.” Journal of Education and Educational Research 3, no. 2 (May 31, 2023). https://doi.org/10.54097/jeer.v3i2.9045.

Malouff, John, and Einar Thorsteinsson. “Bias in Grading: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Research Findings.” Australian Journal of Education 60, no. 3 (August 26, 2016): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944116664618.

Maltese, Adam V., Robert H. Tai, and Xitao Fan. “When Is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math.” High School Journal 96, no. 1 (2012): 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.2012.0015.

Marzano, Robert J. “Grades That Show What Students Know.” ASCD 69, no. 3 (November 1, 2011). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/grades-that-show-what-students-know.

Mathews, Jay. “I Thought at Least 50 Percent Credit for No Work Was Okay. I Was Wrong.” Washington Post, October 27, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/10/23/dc-schools-grading-policy-50-percent-rule/.

McKibben, Sarah. “‘Antiracist’ Grading Starts with You.” ASCD 78, no. 1 (September 1, 2020). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/turn-and-talk-antiracist-grading-starts-with-you.

Minock, Nick. “Va. teachers push back on equity proposal to abolish some grades, late homework penalties.” WJLA, January 1, 2022. https://wjla.com/news/crisis-in-the-classrooms/va-teachers-push-back-on-equity-proposal-to-abolish-some-grades-late-homework-penalties.

Nelson, Paul. “Schenectady Schools Adopt New Equity Grading System Aimed at Equity and Empowering Teachers.” Times Union, October 9, 2023. https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/schenectady-schools-adopts-new-equity-grading-18415330.php.

O’Connor, Ken. A Repair Kit for Grading: 15 Fixes for Broken Grades. London, United Kingdom: Pearson, 2011.

O’Donnell, Patrick. “Mastery Learning Backers Launch New HS Transcript to Help Grads Apply to College.” The 74, March 9, 2023. https://www.the74million.org/article/as-schools-embrace-mastery-learning-and-confront-challenges-of-gpas-and-college-admissions-consortium-creates-new-bridge-transcript/.

Pattison, Evangeleen, Eric Grodsky, and Chandra Muller. “Is the Sky Falling? Grade Inflation and the Signaling Power of Grades.” Educational Researcher 42, no. 5 (June 2013): 259–65. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X13481382.

Quinn, David M. “How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading.” Education Next 21, no. 1 (November 2, 2020). https://www.educationnext.org/how-to-reduce-racial-bias-in-grading-research/.

Ramaprabou, V., and Sasi Kanta Dash. “Effect of Academic Stress on Achievement Motivation among College Students.” i-Manager’s Journal on Educational Psychology 11, no. 4 (April 2018): 32–36. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184179.pdf.

Randall, Jennifer, and George Engelhard. “Examining the Grading Practices of Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26, no. 7 (October 2010): 1372–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.03.008.

Randazzo, Sara. “Schools Are Ditching Homework, Deadlines in Favor of ‘Equitable Grading.’” Wall Street Journal, April 26, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/schools-are-ditching-homework-deadlines-in-favor-of-equitable-grading-dcef7c3e.

Resh, Nura. “Justice in Grades Allocation: Teachers’ Perspective.” Social Psychology of Education 12, no. 3 (September 1, 2009): 315–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-008-9073-z.

Sanchez, Edgar I. “Evidence of Grade Inflation Since 2010 in High School English, Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Courses.” ACT, August 2023. https://www.act.org/content/dam/act/secured/documents/Evidence-of-Grade-Inflation-in-English-Math-Social-Studies-and-Science.pdf.

Schemmel, Alec. “Portland School District Workshops ‘Equitable Grading Practices’ That Outlaw Zeros for Cheating, Missing Work.” Blog. Washington Free Beacon, August 21, 2023. https://freebeacon.com/campus/portland-school-district-workshops-equitable-grading-practices-that-outlaw-zeros-for-cheating-missing-work/.

Schinske, Jeffrey, and Kimberly Tanner. “Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently).” CBE Life Sciences Education 13, no. 2 (2014): 159–66. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.CBE-14-03-0054.

Schwartz, Katrina. “How Teachers Are Changing Grading Practices with an Eye on Equity.” KQED, February 11, 2019. https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/52813/how-teachers-are-changing-grading-practices-with-an-eye-on-equity.

Silverman, Julia. “After more Oregon students failed classes during the pandemic, state takes another look at ‘equitable grading.’” Oregon Live, September 19, 2023. https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2023/09/after-more-oregon-students-failed-classes-during-the-pandemic-state-takes-another-look-at-equity-grading.html.

Sparks, Sarah D. “This One Change from Teachers Can Make Homework More Equitable.” Education Week, December 5, 2022. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/this-one-change-from-teachers-can-make-homework-more-equitable/2022/12.

Stevens, Dannelle, and Antonia Levi. “Leveling the Field: Using Rubrics to Achieve Greater Equity in Teaching and Grading.” Essays on Teaching Excellence, Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education 17, no. 1 (2005). https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/edu_fac/86.

Strauss, Valerie. “Seven things research reveals — and doesn’t — about Advanced Placement.” The Washington Post, July 19, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2018/07/19/seven-things-research-reveals-and-doesnt-about-advanced-placement/.

Swiderski, Tom, and Sarah Crittenden Fuller. “Student GPA and test score gaps are growing—and could be slowing pandemic recovery.” Brookings, November 6, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/student-gpa-and-test-score-gaps-are-growing-and-could-be-slowing-pandemic-recovery/.

TNTP. The Opportunity Myth. Report. New York, NY: TNTP, 2018. https://opportunitymyth.tntp.org.

Tyner, Adam. Think Again: “‘College Admissions Exams Drive Higher Education Inequities.’” Policy brief, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, February 21, 2023. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/think-again-college-admissions-exams-drive-higher-education-inequities.

Tyner, Adam, and Michael J. Petrilli. “The Case for Holding Students Accountable.” Education Next 18, no. 3 (May 15, 2018). https://www.educationnext.org/case-for-holding-students-accountable-how-extrinsic-motivation-gets-kids-work-harder-learn-more/.

Tyner, Adam, and Seth Gershenson. “Conceptualizing Grade Inflation.” Economics of Education Review 78 (October 1, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102037.

Vidal-Fernández, Marian. “The Effect of Minimum Academic Requirements to Participate in Sports on High School Graduation.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 11, no. 1 (August 17, 2011). https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2380.

Walsh, Melony Leane. “Flexible Deadlines and Their Effect on the Turn in Rate of Assignments in a High School Chemistry Class.” Theses and Dissertations at Montana State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.montana.edu/xmlui/handle/1/15706.

Wexler, Natalie. “Why Homework Doesn’t Seem to Boost Learning—And How It Could.” Forbes, January 3, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nataliewexler/2019/01/03/why-homework-doesnt-seem-to-boost-learning-and-how-it-could/.

Whipple, Guy Montrose. “Editor’s Preface.” In The Marking System in Theory and Practice, Vol. 10. Education Psychology Monographs, 1913. https://books.google.com/books?id=4wsRAAAAMAAJ&oe=UTF-8.

Winger, Tony. “Grading to Communicate.” Educational Leadership 63, no. 3 (November 2005): 61–65. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ745459.

Wong, Alia. “Why Millions of Teens Can’t Finish Their Homework.” The Atlantic, blog, October 30, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/10/lacking-internet-millions-teens-cant-do-homework/574402/.

Zhang, Dalun, Hsien-Yuan Hsu, Oi-man Kwok, Michael Benz, and Lisa Bowman-Perrott. “The Impact of Basic-Level Parent Engagements on Student Achievement: Patterns Associated with Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status (SES).” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 22, no. 1 (2011): 28-39. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1044207310394447?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2.

Zimmerman, Alex, and Christina Veiga. “It’s Official: NYC Relaxes Grading Policies in Wake of Massive Shift to Remote Learning.” Chalkbeat, April 28, 2020. https://www.chalkbeat.org/newyork/2020/4/28/21240100/nyc-school-grading-policy-coronavirus/

About the Report

This report was made possible through the generous support of the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. We are grateful to Tim Daly, CEO of EdNavigator, and Sarah Ruth Morris, doctoral candidate at the University of Arkansas, for their feedback on a draft. We also extend our gratitude to Pamela Tatz for copyediting. At Fordham, we would like to thank Meredith Coffey and Adam Tyner for authoring the report; Amber Northern, David Griffith, Daniel Buck, Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Michael J. Petrilli for reviewing drafts; Victoria McDougald for her role in dissemination; and Stephanie Distler for developing the report’s cover and coordinating production.