- The rapid growth of higher education in developing nations has led to a mismatch between the number of graduates and available jobs, contributing to high rates of unemployment and illegal migration within the college-educated population. —Jon Emont, Wall Street Journal

- A new study suggests that charter school expansion and abuse scandals have led to the decline of Catholic schools in recent decades. Could ESAs put a stop to this trend? —The 74

- The control variables typically included in observational studies are not enough to account for the complex factors that motivate human choice, suggesting that causal claims made in such studies may be unreliable. —Emily Oster, Parent Data

- Trump’s vision for education, which includes both closing the Department of Education and expanding the federal role to review curricula for “wokeness,” is contradictory and difficult to implement. Harris’s is too vague, with few specifics and a focus instead on attacking Trump’s plan. —Laura Meckler, The Washington Post

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- Chad Aldis, J.D., is in the house! He discusses various aspects of the rhetorical dust up (not yet a legal one, but highly likely) over state funding recently awarded to religious private schools for facilities projects. Was the move unconstitutional? Chad doesn’t think so: “The long-time purpose of capital budgets is for community projects and things that benefit individual communities. And regardless of one's position is on private schools or religious schools, I think these institutions do play very important roles in their communities.” Does he think a formal legal challenge to the awards will come anyway? “People are questioning whether it’s legal and they have every right to do that.” So…yeah. (Gongwer Ohio, 10/14/24)

- Aaron Churchill, S.R.C.G.*, is also in the house! He discusses Cleveland Metropolitan School District’s report card results for this year. This includes his preference for data-based accountability systems over a “vibes-based” version and the importance of the Progress Component for really showing how most Cleveland schools are performing. Good stuff. (Signal Cleveland, 10/16/24) *State Report Card Guru™

- We learned in yesterday’s meeting of the Columbus City Schools’ board that they have hired an outside consultant to help them move forward on their school closure process. The Dispatch article is concerned about how much he’ll be charging (whatever it is, it’s too much; I would have done it for you for bus fare). Of more concern to me are the wishy-washy comments of several elected board members regarding the process writ large—which has already gone on too long with nothing to show but a list of school names on paper and a whole lot of electronic ink spilled. They are making things too complicated, I reckon, and I get the impression it’s being done that way on purpose. (Columbus Dispatch, 10/16/24) Speaking of overcomplication, the elected board that runs Dayton City Schools has engaged some outside folks for a project—at what seems a reasonable price, given other recent district spending patterns—but this still feels like a waste of time and money to me for several reasons. The stated goal is “creating a space where students in the district can graduate ready to work in well-paying jobs in the area” which, if you ask me (they did not—no one ever does) actually has a very simple solution that can be implemented without spending any additional money: Teach your kids to a higher standard. Take it from me for free—if your high schoolers are good at math and writing and science, they’ll find colleges and employers clamoring to claim them before they even graduate. The other problem is that the actual goal—what their consultants will be producing for them—is some kind of “durable system” (of…something) that is intended to stay in place even as boards and superintendents and central office staffers change. As the current supe explains it, “[W]hat can we put in place that outlasts people?” To which I say: All the money in the world will not Dayton City Schools anything like that, sir. And even if you get it, it will have no positive impact on your students whatsoever. (Dayton Daily News, 10/15/24)

- Here’s a brief but very nice profile of Lorain Bilingual School and one of the charter school’s teachers. Not that you’d know it was a charter school based on this piece. But I know you know, and that’s all we can hope for for now. (Spectrum News 1, 10/14/24)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Fordham recently published results from a parent survey on educational opportunity in Ohio. Produced in partnership with 50CAN and Edge Research, the nationwide survey collected feedback from more than 20,000 parents and guardians of school-aged children in all fifty states and the District of Columbia. In Ohio, the survey was completed by 408 parents. Here’s an overview of three significant takeaways from the Ohio-specific results.

1. Ohio parents have access to school choice and like it.

Over the last few decades, Ohio policymakers have consistently expanded school choice options for families. The most recent state budget, for example, broadened voucher eligibility, increased funding for charter schools, and improved transportation guidelines (though recent events prove there’s still plenty of work to do on that front). According to survey results, those efforts have paid off. On average, 68 percent of parents feel like they have a choice in what school their child attends, slightly higher than the national average of 65 percent. More than two-thirds (67 percent) say they would make the same choice again. It’s telling that the vast majority of Ohio parents say that they feel like they have a choice and would make the same choice again.

Even better, a whopping 71 percent of low-income parents in Ohio reported feeling like they have a choice compared to 61 percent nationally. Historically, economically disadvantaged families have the least amount of choice. That’s because high-performing districts require residency for enrollment, and real estate prices are typically beyond the financial reach of many families. Private school tuition is also steep. But in Ohio, options like charter schools (which posted stronger academic growth numbers than their district counterparts this year), private school scholarship programs, and open enrollment provide low-income families in all communities—urban, suburban, and rural—with more choices than they would have otherwise. Families can, and often do, choose to enroll their children in their assigned traditional public school. But Ohio parents saying they feel like they have options matters because choice shouldn’t be limited by income.

2. Few parents seem to be consuming Ohio’s information on schools.

Each year, Ohio’s school report cards offer families, stakeholders, and policymakers a wide variety of data about school performance and student outcomes. Unfortunately, survey results indicate that many Ohio parents may not realize they have a treasure trove of data at their fingertips. On average, only 28 percent said they reviewed information about their school’s performance compared to other schools. That matches the national average, but twenty-four states registered higher percentages. Even worse, there’s an alarming gap between families of different income levels. More than a third (34 percent) of middle- and high-income parents reported that they reviewed school performance data. But less than a fifth (18 percent) of low-income parents did so. That means low-income families are viewing school performance data at roughly half the rate of higher-income families.

It’s unclear what’s causing this gap. It could be that families are not aware of school report cards, let alone choosing to use them to compare school performance. But it’s also possible that they feel Ohio’s system is difficult to navigate or that online report cards aren’t as user-friendly as they could be. Either way, state and local leaders need to do a better job of communicating with parents, especially those in low-income communities.

3. Most Ohio parents don’t believe their children are ready for the next step.

Ensuring that students are ready for what comes after graduation is a top priority for families and one of the chief responsibilities of schools. But survey results show that Ohio parents have some concerns. Only 39 percent are “extremely confident” that their child will be well equipped to succeed in the workforce, and only 36 percent feel that way about college preparation. On the one hand, both numbers are higher than the national average, which is 34 percent for workforce preparation and 32 percent for college. That means Ohio fell into the top tier among other states. But on the other hand, only a third of Ohio parents believe that their kids are ready for the next step, whether it's work or higher education. That’s worrisome.

***

Results from parent surveys like this are incredibly useful for policymakers. They pinpoint areas where policies and programs have been successful, like school choice expansion. They also identify areas for growth, like ensuring parents are aware of school performance data and prioritizing initiatives aimed at improving student readiness. Here’s hoping Ohio leaders pay close attention to these results as they head into budget season.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- The members of the Cleveland.com Editorial Board responded individually on the topic of chronic student absenteeism this weekend. While their suggestions for solutions ran the gamut (court action, information campaigns, better data, etc.), the members appear unanimous in pointing to parents as the source of both problem and solution. (Cleveland.com, 10/12/24)

- As I noted last Wednesday, no news outlet here in Columbus has actually confirmed that the charter school students who were to be provided with transportation to school—starting last week, while their long-term transportation mediation was ongoing—have actually made it to school on a yellow bus yet. Attorney General Dave Yost actually told the Dispatch on Friday that “the state already has received some information suggesting” that district buses are still not properly rolling, even for these few dozen charter school students. This is just one of the reasons he is vowing to keep the legal pressure up on the district to fulfill their transportation responsibilities. (Columbus Dispatch, 10/11/24)

- Toledo Maritime Academy posted another poor report card this year, making it two in a row for the much-loved charter school. Even if they boost that in next year’s report card, the return of pre-pandemic accountability measures for Ohio charters means that they will face the possibility of automatic closure. Staff members are struggling with this reality. “I believe in accountability, and I believe in the report cards,” school superintendent Aaron Lusk told WTOL-TV News. But, “[w]e need more time because of the specific nature of our school.” Lusk also notes what he sees as a conundrum in the rules: “Community schools are supposed to be innovative. They’re supposed to be different than public schools. But we’re held to the same measure…” as traditional district schools, “…but also held to an automatic closure law.” Which traditional district schools most decidedly are not. (WTOL-TV, 10/13/24)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Editor’s note: This was first published by The 74.

Say your boss gives you an unexpected bonus at work. Would you save the money, make those home upgrades you’ve been putting off or splurge on a nice vacation?

School districts had to make similar calculations with the financial windfalls they received in the wake of Covid-19. Known officially as the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Funds—ESSER—$190 billion was disbursed by Congress to schools and districts in three installments from March 2020 to March 2021.

It was the largest one-time infusion of federal funds ever, and the money officially expires at the end of September. So what have researchers learned about ESSER, and what should it mean for future federal investments?

Any evaluation of the ESSER funding has to start by defining its purpose. Was it intended as a financial lifeline for a large and important public-service sector in the midst of a turbulent economic climate? Was it supposed to nudge schools to reopen their doors for in-person instruction? Or was it meant to help re-engage students and help them address learning loss?

Congress essentially took an “all of the above” approach. It did specify that 20 percent of the last round of ESSER funding be directed toward addressing learning loss, but the allowable activities were extremely broad and inclusive. Without a clear purpose or goal, districts could—and did—spend their money in wildly different ways.

The result is that no one really knows how districts spent their ESSER money. Marguerite Roza and the team at Edunomics Lab did yeoman’s work of collecting what spending data they could find from state reports, but it’s far from a comprehensive story.

When AASA, The School Superintendents Association, surveyed its members recently, it concluded that the wide diversity of investment strategies with the ESSER money “does not illustrate or support any additional trends within specific categories.” They found that districts spent the funds on tutoring, summer, and afterschool programs, facilities, professional development for teachers, supports for English learners and students with disabilities, early-childhood programs, and a host of other activities. At an event marking the survey’s release, the superintendent from Umatilla, Oregon, highlighted her district’s choice to invest in a cadre of substitute teachers who could be deployed as needed. The superintendent of schools in Fargo, North Dakota, emphasized the large number of initiatives his district launched and cautioned that those should be evaluated one by one rather than as a group.

Congress could have set clearer priorities and set aside funding dedicated to specific initiatives, such as tutoring. But it may have been justified in deferring to local communities. Research on school finance has found that, in general, additional money helps boost a variety of student outcomes, but there’s still an open debate about how funds should be distributed and spent. So flexibility was probably the right bet during a period like Covid.

But without greater clarity on goals, the question of whether ESSER funding worked is hard to answer.

Did the program provide a financial lifeline to schools and districts in an uncertain economic climate? That answer is an unequivocal yes. The early rounds of funding helped districts pay for personal protective equipment like masks, upgrade their technology, and begin to re-staff schools after Covid layoffs and hiring freezes.

Did ESSER convince districts to reopen their schools? That’s less clear. The first round of funds, which were approved in March 2020, wasn’t enough to help most schools reopen their doors to in-person learning the following fall. And the last round, approved in March 2021, probably came too late to have an effect. According to the AEI Return to Learn tracker, only 7 percent of districts were fully remote by the time the last round of ESSER passed, and half of all districts remained fully remote or hybrid through the end of that school year.

Did ESSER boost student outcomes? The early answer to that question appears to be yes, it did lead to meaningful improvements. By identifying districts that happened to get more or less money, two separate research teams found that the ESSER funds helped boost outcomes by a similar amount as past financial investments did.

But did ESSER provide the right amount of money? The answer here is yes and no. The “no” side is dominated by practical realities. One-time windfalls are hard to handle, especially in an industry like education, where 85 percent to 90 percent of expenditures are tied to salaries and benefits. In a detailed report on the ESSER funds, New America’s Zahava Stadler quoted a school business official as saying, “While [it was] fantastic that schools had these resources to be able to get through Covid and then try to recover … those big Title I districts got so much money in such a short amount of time. [It’s] really hard to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on one-time expenditures within that window.”

It’s also hard to ignore the fact that the expiration of the money will likely lead to a fiscal cliff as districts scale back. How bad will that be? One way to estimate it is to note that, according to data compiled by FutureEd, districts had about $67 billion in ESSER funds left to spend as of one year ago. That money is now all about gone, and the states are not in a position to fill the gap. This is likely to lead to potentially large program and staffing reductions, which would be destabilizing for schools and bad for kids.

But the other way to look at this question is from the student perspective. It’s fair to conclude that students would likely be far worse off in the absence of the ESSER funds, and they remain so far behind pre-Covid performance levels that researchers estimate it would take an additional $450 billion to $900 billion to get kids fully back on track.

No policymaker is seriously talking about making additional investments on anything close to this sort of scale. But focusing on student learning needs should be the ultimate goal, and that’s a discussion policymakers should be having as the ESSER funds wind down.

Stories featured in Ohio Charter News Weekly may require a paid subscription to read in full.

New panelists announced; last change to register for October 17 event!

Has more equitable funding improved Ohio charter schools? Join us for an in-person event in Columbus on Thursday, October 17, to find out! Senior Research Fellow for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and professor at The Ohio State University, Stéphane Lavertu, will be presenting his analysis about the impacts of Ohio’s Quality Community School Support Fund. Discussing those findings will be a panel of charter leaders including Anthony Gatto, Executive Director of Arts and College Preparatory Academy (ACPA) and Ciji Pittman, Superintendent of KIPP:Columbus. The event will be held at the Athletic Club of Columbus. Doors open at 8:30 am – with a light breakfast available – and the program begins at 9:00 am. Register now to attend!

Charter enrollment surges

Important new research released this week by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools looks at school enrollment trends across the country over the last five years. That is, before, during, and after pandemic-disrupted school years. Overall, the charter sector is showing significant growth while traditional district schools have seen sharp enrollment declines. The charter surge is led increasingly by Hispanic and Black students and charter schools are outperforming expectations based on documented population changes across most states. You can download the full report here.

Even more good news

More important research: The Progressive Policy Institute’s latest report shows that charter school expansion in several cities has contributed to a substantive reduction in the achievement gap between low-income students and their wealthier peers. The analysis looks specifically at student performance in 10 U.S. cities with the largest charter sectors (including Dayton) between 2011 and 2023. Overall, cities that have aggressively expanded high-quality charters have seen what PPI terms “a true rising tide”: Low-income students starting to catch up to statewide student performance levels, regardless of whether they attend one of those charters or a district-operated school. This effect is particularly pronounced when at least one-third of a city’s students are enrolled in a charter (or “charter-like”) public school. Incredible news! You can read the full report here.

More high-quality charter schools needed

Fordham Institute president Mike Petrilli cites the new NAPCS report in a blog post this week. In it, he notes that the population of school-age children will likely continue to decline for many years to come. That means more schools will have to close—including charters—but that doesn’t mean the charter sector shouldn’t continue to expand. And the key is quality. “Let’s remember what we stand for, charter community: quality choices for families,” he concludes, noting that low-performing schools of all kinds should be first on the chopping block. “As long as [quality choices] are scarce, we need more great charter schools, not fewer.”

Speaking of school closures…

It is still the case that charter schools can close due to lack of enrollment, and Victory Academy in Toledo will unfortunately do so next Friday. While the school’s closure mid-year is a worst-case scenario, this coverage indicates that school leaders are doing everything they can to mitigate the upheaval for families. This includes timing the closure for the end of a grading period, inviting as many other schools as possible to conduct a school fair on site so families can make informed choices of where to go, and facilitating paperwork transfer to smooth the transition.

Petitioning the court

Leaders of the proposed St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School and Oklahoma’s charter school board filed petitions last week with the U.S. Supreme Court, asking the justices to take up their case and rule on the legality of the first religiously-affiliated charter school proposed in the country.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- A 2020 Fordham report by Aaron Churchill is referenced (but not linked—shame on you NBC 4) in this piece on the history of Ohio’s school funding system and how it relates to the school levies on the ballot in the general election right now. (NBC4 News, Columbus, 10/10/24)

- Leave it to some class act charter school leaders in Toledo to show how you properly close a school when the need arises. (13 ABC News, Toledo, 10/9/24)

- Kudos to Parma City Schools on their high-scoring (and very popular, it seems) CTE report card for 2023-24. “It’s just a very high percentage of our students who are getting very high-quality, hands-on preparation for whatever career they may choose to pursue,” says district supe Charles Smialek. Nice. (Cleveland.com, 10/10/24)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

The macro trend that will have the greatest impact on the American education system over the next decade or two is our declining birth rate and the resulting enrollment crisis facing many public schools. We have too many schools for too few kids and, as a result, thousands of schools are going to need to close.

With students in short supply, then, one can understand the natural impulse to say that we should slow down or even halt the creation of new schools, including charter schools. Why make the problem of excess capacity even worse than it already is?

But policymakers and those of us in the charter school movement need to resist that line of thinking—indeed, we need to combat it hard and fast. That’s because what’s in even shorter supply than students are high-quality schools. Yes, we have too many school buildings in many communities in America. But we don’t have nearly enough excellent schools. And fixing that should continue to be the mission of the charter school sector.

Not surprisingly, charter opponents see it different. Teachers unions and their allies would love to use this moment to cap the growth of charter schools, even roll them back. And unfortunately, some sensible people are starting to listen to them. In Washington, D.C., for example, Mayor Muriel Bowser, who has been relatively friendly to charter schools during her two-plus terms in office, published a “boundary and student assignment study” that calls for the D.C. Public Charter School Board to consider the impact of new charters on enrollment in individual D.C. Public Schools before approving them.

This is deeply wrongheaded. Imagine if we had adopted that same line of thinking twenty or thirty years ago, during the last big period of urban school closures. We would have thousands fewer charter schools than we do today, and hundreds of thousands of kids would be worse off. We know that because of the overwhelming and growing evidence that students in charter schools, especially in urban charter schools, learn dramatically more year over year than their counterparts in traditional school districts, and achieve stronger real-world outcomes, too.

If our priority is to remediate learning loss, boost achievement, and improve long-term prospects for low-income students, then creating great schools where students can thrive must be job number one. That means growing the charter school movement.

Charter schools should close, too

That’s not to say the charter sector shouldn’t also take its fair share of lumps. It’s always a good time for authorizers to close low performing charter schools, but being aggressive makes more sense now than ever. Rather than showing patience while time and the marketplace take their course for schools in a downward spiral of declining enrollment and/or weak achievement, authorizers might step in and close schools more urgently. Not only will that put failing charter schools out of their misery, but it will free up market share, and potentially free up buildings, for other higher-performing charter schools to tap.

We at Fordham recently released a study by Sofoklis Goulas of the Brookings Institution which identified almost 500 public schools that are both low achieving (according to their own states) and which have seen enrollment drop significantly in recent years. As we wrote in the report, not all the schools on that list should necessarily be closed, as the way states define quality is not always ideal, and there might be local context that needs to be considered. Still, the 500 schools should at least be candidates for closure.

And guess what: Some of these are charter schools—sixty-three to be exact, although subtracting the “dropout recovery schools” that wound up on that list due to their low graduation rates brings down that number to thirty-nine.

Closing some of these schools would demonstrate that the charter sector is serious about quality and would underscore the principle that school effectiveness should be a factor when deciding which campuses to shutter. That would also give the charter movement the moral high ground to demand that districts also prioritize school quality when making these decisions.

But let’s not be naïve. Charter opponents will scream bloody murder when they see authorizers approving new schools or growing or replicating existing ones at the same time that districts are shuttering campuses. We shouldn’t be shy about defending such a course of action, especially since charter school growth is not the primary reason that district schools are emptying out. That might have been the case in the 1990s or 2000s, when the charter sector was growing like gangbusters, but as a brand-new analysis by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools illustrates, only some of recent district enrollment declines are connected to charter growth. No, districts have mostly themselves, plus demographic trends, to blame. And the longer they wait to take action, the more painful it will become.

We know it’s been easiest for the charter sector to grow in places where public-school enrollment as a whole was also growing. It’s no accident that Arizona was the fastest-growing charter state for many years, given that the Grand Canyon State as a whole was attracting families at a record clip. Its districts couldn’t possibly keep up and, as a result, the charter sector enjoyed much support and relatively little opposition.

But now we face the opposite dynamic, at least in much of the country. That creates a zero-sum political environment, one where we should expect sharp elbows to be more common than open arms.

Let’s remember what we stand for, charter community: quality choices for families. As long as those are scarce, we need more great charter schools, not fewer.

As the clock winds down towards Election Day, Colorado voters—myself included—face an important decision beyond the presidential contest: whether to amend the state constitution to enshrine a “right to school choice.” To be clear, the Centennial State has a long and proud record on the issue. Fifteen percent of all Colorado public school students—my nine-year-old daughter among them—attend charter schools. More than a quarter participate in open enrollment within or across traditional district boundaries. Yet the state lacks a private school choice program (though it once had a short-lived district-level voucher program). This is where proponents and opponents of Amendment 80, the “Constitutional Right to School Choice Initiative,” part ways on the implications of this measure, should it come to fruition.

Simply worded and seemingly innocuous, the ballot measure comes in at around one-hundred words:

Be it Enacted by the People of the State of Colorado:

SECTION 1. In the constitution of the state of Colorado, add section, 18 to article IX as follows:

Section 18. Education - School Choice (1) Purpose and Findings. The people of the state of Colorado hereby find and declare that all children have the right to equal opportunity to access a quality education; that parents have the right to direct the education of their children; and that school choice includes neighborhood, charter, private, and home schools, open enrollment options, and future innovations in education.

(2) Each K–12 child has the right to school choice.

Sponsored by a conservative non-profit group, it requires 55 percent of the vote to pass. Whether it reaches that threshold remains to be seen, but similar school choice initiatives in Colorado have failed in the past, even when the state leaned Republican.

Supporters of the measure, which include the Colorado Association of Private Schools and the Colorado Catholic Conference, are pushing for its passage as a hedge against the teachers unions and their backers, who have vehemently opposed all alternatives to the traditional system. While the amendment likely wouldn’t affect Colorado’s “Blaine Clause”—a provision that prohibits the use of public funds to support religious schools—now arguably a dead letter in the wake of recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions, proponents say that a constitutional right to school choice would serve as a last line of defense. This would be crucial should the legislature (or a local school board) do something completely out of bounds. From imposing burdensome regulations upon private schools to cracking down on homeschooling, advocates are trying to cover all their bases. Additionally, it could provide greater protections for charter schools, which have been increasingly under threat in recent years. For instance, it could empower parents to challenge denials of charter applications by local school districts.

The opposition spans a laundry list of characters from the teachers unions to libertarians wary of government interference. The former label the measure a “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” claiming that it paves the way for public funding of private schools, while the latter argue that the proposal undermines parental rights and opens the door to government overreach. One local columnist made no bones about his skepticism:

When [the measure] likely fails, the enemies of educational choice will cry, “The people have spoken, and they don't want school choice. It's a mandate.” And it has been tough enough to keep charter schools safe from this choice-hating legislature.

[The measure] does not create a new school choice program (or even framework for a program) of any kind. It only creates a new avenue for lawsuits that may or may not lead to some sort of jurisprudence many years in the future.

Should it pass, [the measure] would put a “right to school choice,” including “private” schools, in the Colorado Constitution, but doesn’t define what “private schools” means. The legislature and the courts will have to interpret it, and that could lead to regulating private schools.

Alarmed by the prospect of government encroachment, homeschoolers, in particular, are vocally in opposition to the measure.

Colorado’s main charter school organization is attempting to stay above the fray. (Full disclosure: I serve on its board of directors.) So is the state’s pro-charter governor—a Democrat. While there’s a lot to like about codifying a child’s right to school choice, the proposed amendment places charter schools in a politically tricky position. Republicans are currently the only party willing to support them, and charters have become verboten among Democrats (save for the state’s Democratic governor!). Making matters worse, the amendment could create confusion about the judiciary’s role. As one local professor quipped, “[The measure] really is a ‘full employment for lawyers’ act. It puts judges in the driver’s seat later on to try to make some sense out of this.”

With fourteen statewide measures on the ballot, proponents have their work cut out for them. What they might perceive as straightforward, critics view as ambiguous. With a presumption of good intentions from the measure’s sponsors, history and experience suggest that more preparation and groundwork were needed to rally and unify Colorado’s disparate school choice stakeholders around any referendum. Should this one go down in defeat, it may be because this latest iteration of school choice advocacy became more about political theater than substantive policy.

Chicago’s troubled school district has made national headlines recently—from the mass resignation of its appointed school board, which opposed the mayor’s efforts to borrow nearly $300 million at ruinous rates to give the teachers union a sweetheart contract, to the likely ouster of the district’s superintendent. But the city has also become a powerful symbol in the brewing battles over rightsizing efforts in the face of declining enrollment and expiring federal pandemic aid.

A decade ago, Chicago closed approximately fifty schools, one of the largest consolidation efforts in recent memory, and the consequences continue to be disputed. Much of this debate engages in selective cherry-picking of data and misleading interpretations of the evidence, giving rise to confusion about what (if any) lessons district leaders across the country should learn from Chicago’s experience.

A recent article by Thomas Toch, director of Georgetown University think tank FutureEd, and Maureen Kelleher, a freelance writer and FutureEd's former editorial director, suffers from many of the same problems. To understand the many things the authors get wrong about Chicago—as well as the few points they get right—it is important to examine the most important claims in their piece.

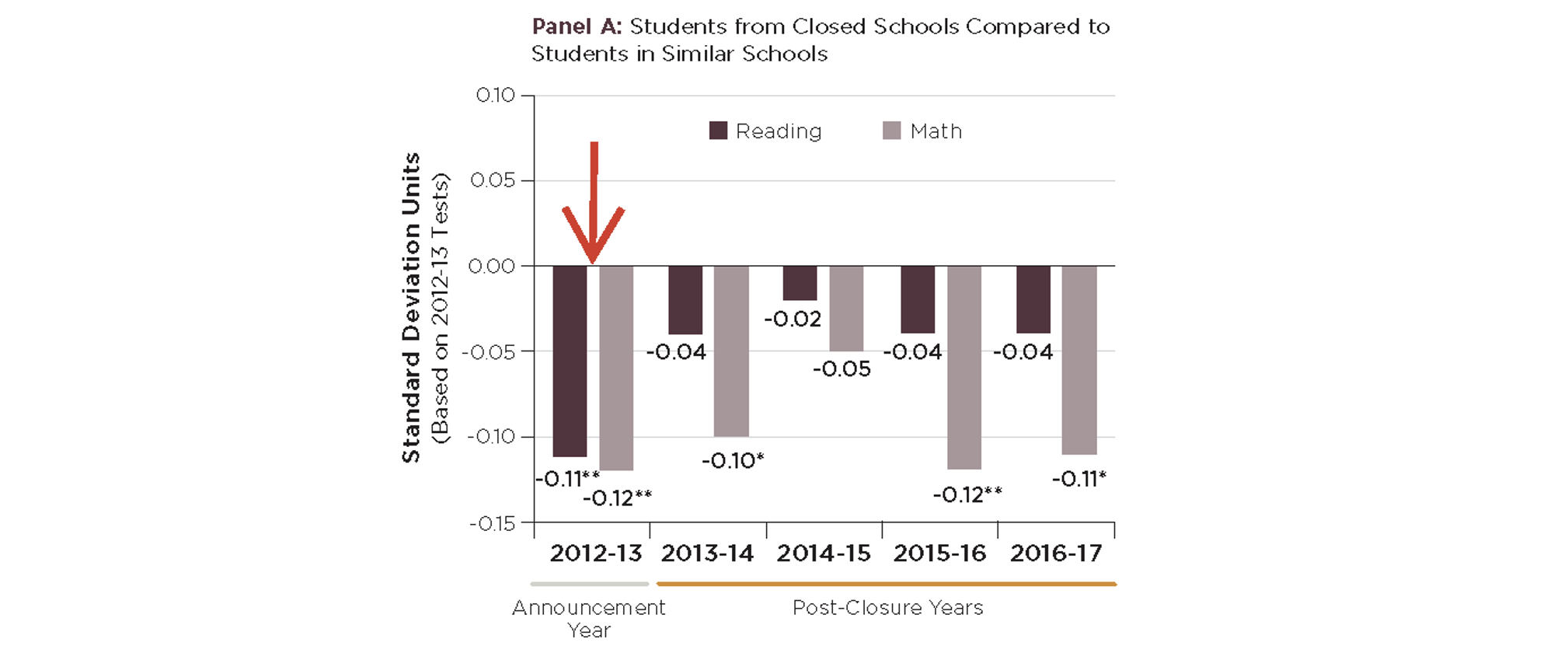

Claim: School closures caused student achievement to decline

“Shuttering the schools didn’t improve academic outcomes for their students,” Toch and Kelleher wrote, noting that displaced students “had lower math scores for at least four years after transferring.”

I’ve emphasized before that this is highly misleading. As the careful University of Chicago evaluation of Chicago’s closures showed, all the negative achievement impacts occurred in the year that planned consolidation was announced—before a single school had closed. This can be seen in the figure below, which is taken directly from the report. I’ve added a large red arrow over the announcement year, which corresponds to the test score drop.

The most likely explanation for the decline is the organized campaign to fight closures and the associated circus and psycho-drama that these efforts created. (This is also the reason the University of Chicago evaluation proposed to explain the increase in absenteeism that same year, speculating that “communities, schools, and families were advocating for their schools not to close” instead of making sure students were attending class.)

Interestingly, achievement began to rebound quickly once the buildings were actually shuttered and students moved to their new schools (although math scores dipped again a few years later). This pattern can be seen in the figure, with the negative effects shrinking in each of the first two post-closure years.

It would also be a huge mistake to draw strong conclusions about the impact of school closures on academic outcomes from Chicago alone. Studies in other cities that have closed a significant number of schools show that well-planned consolidation efforts can move the needle upward on learning.

In Newark, for example, students displaced by closure of their schools saw their achievement improve by between 10 percent and 15 percent of a standard deviation—sizable effects that researchers attributed to “reap[ing] the benefits of moving to higher value-added schools.” In New Orleans, closing low-performing district buildings and reopening them under charter management improved achievement even more. And a few weeks ago, a new study of the “portfolio” reform model in Denver found large gains by students forced to switch schools when theirs closed.

Claim: Closures pushed families to leave the district

Toch and Keller claim that school closures “contributed to the decline of the low-income Black neighborhoods where the schools were located,” citing an analysis published last year by the Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ. That analysis, the authors assert, “found that Black neighborhoods that experienced a permanent school closure in 2013 subsequently lost population at three times the rate of other Chicago Black neighborhoods.”

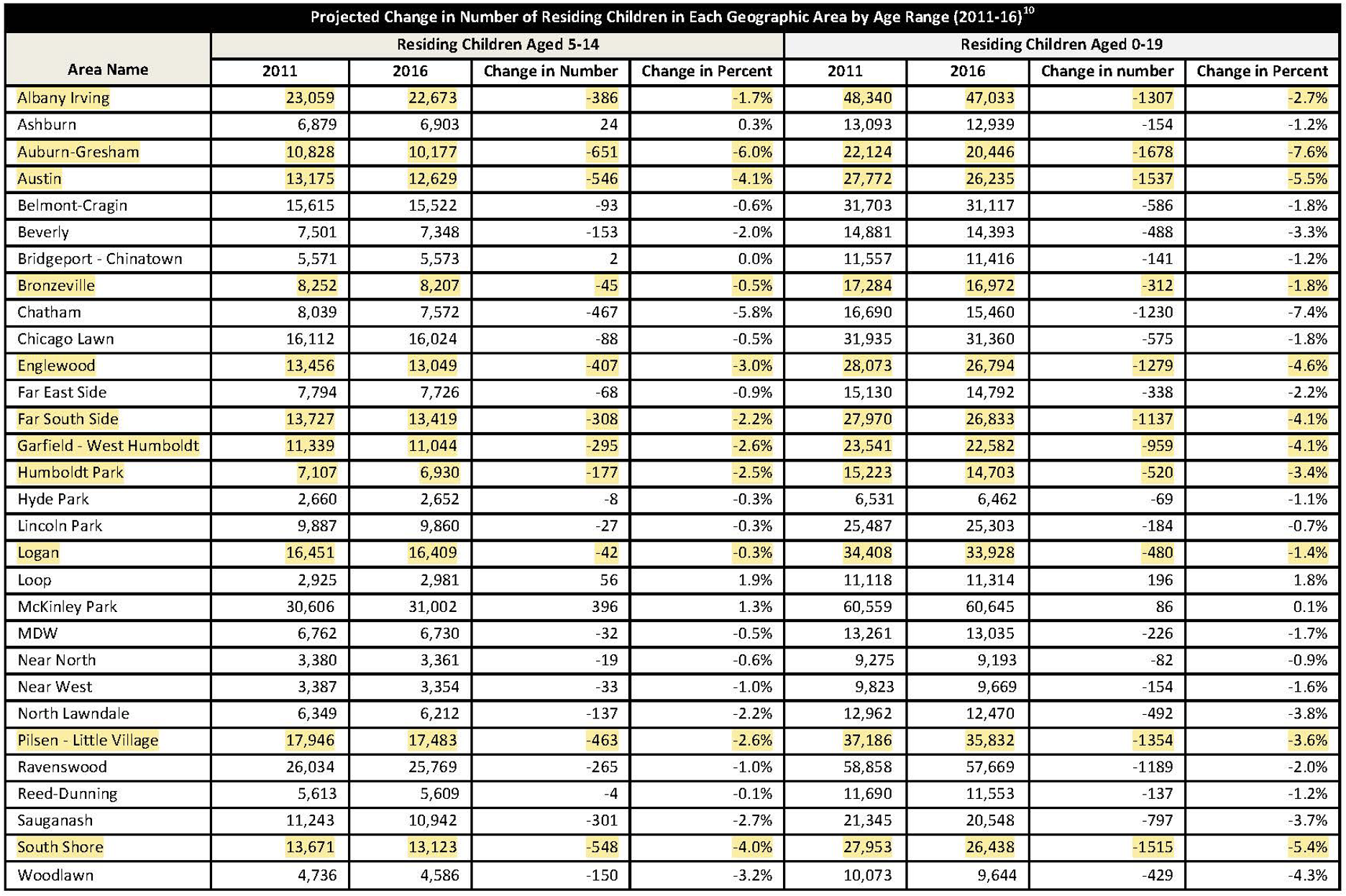

These numbers may be right, but they get the causality backwards: Expected population declines drove school closure decisions, rather than closures driving future population declines.

In the run-up to its 2013 consolidation efforts, Chicago commissioned a massive 450-page facilities plan that included, among other analyses, enrollment projections by neighborhood. The report noted that population had declined significantly between 2000 and 2010 in the heavily Black areas on the city’s South and West Sides and projected that the numbers would keep falling further in the coming years in many of these same places.

The table below, taken directly from the 2013 report, shows the change in the number of children in each Chicago neighborhood anticipated between 2011 and 2016. I’ve also highlighted the areas demographers identified as having already undergone “extreme” population loss over the previous decade—a decline in the number of children of more than 5,000. The key takeaway is that the projections anticipated additional declines in the same neighborhoods where population was already sharply falling years before the closures were announced and where affected schools were located.

That population numbers subsequently declined disproportionately in neighborhoods where schools closed suggests that those projections were accurate and the district was wise to use them to target closures in the places it expected student enrollments to keep falling. These numbers provide no evidence that closures caused population losses above and beyond those that were expected to happen anyway.

Oddly, after claiming that “closures contributed” to the population decrease, Toch and Keller acknowledge this point, noting that the data “don’t prove that the school shutdowns accelerated declines in neighborhoods that were already depopulating.”

Claim: District officials exaggerated the budgetary savings from consolidation

When making the case for their right-sizing efforts, Chicago officials estimated that they would save $1 billion over the next decade—roughly half in the form of avoided capital maintenance and upkeep costs and half by reducing the number of building principals and clerical staff. Toch and Keller are right to note that these estimates proved to be off the mark—although the district did save about $250 million over this period on lower administrative and support staffing levels. To say that the savings were exaggerated does not mean that no efficiencies were achieved.

Importantly, however, the district’s budget projections never took into account (and Toch and Keller never discuss) the main way in which building closures save money: by reducing the number of teachers and aides. Instructional staff account for by far the largest budget item in public education, so it makes sense that closures generate the most cost savings by reducing headcounts in that category.

In research for my forthcoming book, which examines school consolidation efforts across the country over the past two decades, I found that school closures cause teacher employment levels to decline by between 5 percent and 10 percent in the affected districts, with class sizes rising modestly and per-pupil expenditures declining by between $500 and $1,000 per year. The reason closures produce such savings is that even massively under-enrolled schools require a minimum complement of teachers to offer a viable education program. Consolidating these buildings reduces the number of teachers by eliminating half-empty classes.

Given the popularity of teachers—and the political power of their unions—it is not surprising that district officials are loath to advertise the fact that building closures will cause teacher staffing to shrink. It is much easier to claim that cost savings will come from elsewhere. But ignoring the staffing changes among frontline educators dramatically understates the actual efficiencies that consolidation can (and do) unlock.

Bottom line: School closures can work, but must be done right

To their credit, Toch and Kelleher conclude their article by writing, “School districts can’t ignore the inefficiencies of under-enrolled schools, especially when they are faltering academically. But the aftermath of Chicago’s school closings a decade ago points to the importance of a clear-eyed approach that prioritizes public transparency and takes into account the financial, academic and community consequences of closings.”

I could not agree more. When closing schools, districts should prioritize academic considerations—most importantly, shuttering schools that post the smallest year-to-year gains in achievement—instead of using budgetary bean-counting to choose the buildings. Community members should avoid dramatic protests, recognizing that efforts to save schools, however well-meaning, could disrupt learning more than the closures themselves. District leaders should be honest with taxpayers that most of the fiscal savings will come by reducing teacher headcounts, not through savings on utility costs or building maintenance needs. They should carry out these staffing reductions strategically by culling the weakest (rather than least experienced) teachers and not rely on attrition alone. And they should make the vacant buildings available to address their communities’ most pressing needs—allowing strong charters to purchase them to increase access to high-quality education options or working with developers to build badly needed housing.

Executed effectively, school closures can be a lever for positive change. Even in Chicago.