- Some schools and districts are trying to better align college credits earned in high school with the potential majors of their students. —Education Week

- Microschooling founders who want to create safe, effective schools for Black children need vouchers to be sustainable. —The Texas Tribune

- Debates continue over whether teacher licensure exams are racially biased, effective, and/or necessary. —Emma Green, The New Yorker

On October 27, members of the Ohio Attendance Taskforce, which include school and business leaders as well as representatives from the juvenile court system, unveiled a series of recommendations aimed at improving school attendance. Their suggestions couldn’t have come at a better time, as districts and schools across the state continue to struggle with high rates of chronic absenteeism. As numerous reports have documented, absenteeism shot up during the pandemic, has yet to come back down to pre-pandemic levels, and is making academic recovery more difficult.

The taskforce’s recommendations are part of a detailed report that’s worth a read, as it includes a look at how some systems and schools—such as the state’s largest district, Columbus City Schools, and the Dayton Early College Academy (DECA), a charter school in Dayton—are seeing promising results from attendance-boosting efforts. The highlight of the report, though, is its five in-depth recommendations. Let's take a look at each.

1. Working together, build awareness and galvanize statewide support for the role attendance plays in student success in academics, careers, and life.

The report emphasizes that a wide variety of stakeholders—districts and schools, students and families, community members, business leaders, faith communities, and state leaders—have an important role to play in supporting student attendance. It’s absolutely crucial for these groups to work together to address absenteeism. One potential way to do this is by expanding the Stay in the Game! Attendance Network into a comprehensive statewide messaging campaign that every district could join (right now, around thirty-five of the state’s 611 districts participate). The campaign could highlight trends and data, identify best practices, and share the stories of schools that are successfully improving student attendance.

Building local partnerships is also crucial, and the report offers several ideas. For example, healthcare professionals like pediatricians and dentists could make sure to offer appointments before and after school hours so that students don't have to miss class. Local businesses could post signage and informational materials that support school attendance efforts. And neighborhood restaurants could recognize local students with high attendance marks.

2. Foster engagement, build trust and belonging, and address local challenges with students, families, and educators.

Implementing “robust, authentic, and frequent” student and family engagement experiences is critical. Parents and families can’t address problems if they’re not aware of them, and students are more likely to attend school if they feel a sense of trust and belonging.

Schools should view families as “respected allies” when it comes to student attendance. Getting off on the right foot is crucial, so the report recommends beginning each school year by sending home positive messages via text, notes, or emails. Throughout the year, schools should make a concerted effort to reach all families and communicate proactively and regularly. Administrators could establish focus groups to gather information and ideas from families or create roles for parents on district and school leadership teams. Offering families the chance to engage with surveys or other feedback-gathering mechanisms at student performances, school exhibits, or sporting events would make engagement a lot more convenient, too.

Students, meanwhile, can be a big help when it comes to crafting innovative solutions that will appeal to their peers. As such, teachers and administrators should offer plenty of opportunities for students to provide feedback. Schools could create student taskforces that allow them to brainstorm ideas and present solutions on various issues—like absenteeism—to building administration. And districts could include a student as an ex-officio member of the school board who can offer an important perspective that might otherwise be absent.

3. Cultivate engaging and relevant learning environments at all Ohio schools so students want to attend.

“Getting teaching and learning right,” the report notes, “is a strong motivator for student engagement and attendance.” In other words, schools need “engaging and relevant” learning environments that make students want to show up. They can do so in a variety of ways: incorporating hands-on activities and interactive technologies into lessons; connecting academic content to real job opportunities and careers, as well as to real world problems; embedding enrichment activities and clubs into the school day; and ensuring that students have the academic supports they need—things like tutoring, counseling, and mentorship programs—to succeed. It’s also important for districts and schools to offer teachers professional development in classroom engagement and management techniques so they have the knowledge and skills they need to enhance classroom climates.

4. Adjust systems and resources to support schools and districts in their attendance work.

When it comes to boosting student attendance, schools can’t do it all on their own. The Department of Education and Workforce can offer support by integrating attendance across multiple state-led areas, including the Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support framework, school improvement efforts, and health and mental health supports. The department should also identify and disseminate best practices. Creating an Attendance Data Guide and enhancing the data and access tools available to districts and schools could help.

District leaders also play a crucial role in supporting schools. One of the best ways to do so is to track and assess the effectiveness of attendance interventions so that schools can focus on what works. District leaders should also prioritize connecting with regional educational service centers and state support teams to offer staff training and support—especially certified Regional Data Leads, who can offer educators support in data analysis and data-driven decision-making. Meanwhile, in the interest of transparency, districts could create a school or district-level data dashboard that provides the public with real time information about student absences and opportunities for early intervention.

5. Work with policymakers to inform comprehensive policy changes that support student attendance.

In 2016, lawmakers overhauled the state’s attendance policies via House Bill 410. With several years of implementation now on the books, the taskforce wisely asked administrators to share what is and isn’t working. They praised the law for requiring schools to examine attendance data and for providing a standardized process and framework to identify the root causes of student absenteeism. But they also critiqued the law’s focus on compliance (rather than prevention and intervention) and noted that, by prescribing how schools must communicate with families, districts have been prevented from using more effective methods—like, for example, text messaging.

In response to this feedback, the report recommends that lawmakers refine Ohio’s attendance-related policies. The taskforce doesn’t call on the state to do away with HB 410 entirely, which means consequence-related provisions like absence intervention teams and filing truancy complaints with juvenile court would remain intact. But it does call on leaders to shift “allocation and action” away from compliance and toward prevention and early intervention. It also recommends adding flexibility regarding how schools can communicate with families. However, it’s important to note that not all adjustments are good adjustments. For example, a recent legislative effort that would have made it easier for students to miss school would move Ohio in the wrong direction. Going forward, lawmakers should be thoughtful as they consider how to adjust state attendance laws.

***

Nationwide, chronic absenteeism has become a crisis. Ohio is no exception, and it’s important for state and local leaders to not only acknowledge the crisis, but to act. The recommendations released by the Ohio Attendance Taskforce provide a great place to start.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- Let’s start with some legal news. The New York Times took a lengthy look at Reading Recovery’s lawsuit against the State of Ohio, which is aiming to stop the governor’s implementation of the Science of Reading as the law of the land here. “The practical matter is, we have to be able to keep our business going,” says the Reading Recovery Council’s executive director by way of explanation for bringing the fight. “But the stand is principled… We believe that what we do works, and we’ve got evidence to prove that it does work.” Should be a fascinating /trIEUHl/ if it happens, don’t you agree? (New York Times, 11/3/23) In further (and no doubt related) legal news, plaintiffs have filed an objection to the release of a temporary restraining order a couple of weeks ago, an action which allowed the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce to begin fully operating. We’ll see how it goes. (Gongwer Ohio, 11/6/23)

- Two different views of the causes of chronic student absenteeism being discussed in schools across the country. Up first is the national view. It does not include Ohio references, but covers a lot of ground in trying to define causes generally. These include the old standby of illness at the top, but also some newer reasons such as a preference by older teens for work over school, rising incidence of mental health problems among young people, and higher-than-usual teacher absenteeism leading their students to follow suit. (The 74, 11/7/23) Up next is the local view—from one of the leafiest of leafy Ohio suburbs. The elected board that runs Yellow Springs Exempted Village Schools also covers a lot of ground in this discussion of absenteeism in their district. Illness is at the top of their list of causes too, but district officials specify that much of that category consists of “family quarantining”—keeping everyone home following a Covid exposure or diagnosis for one family member. But on the opposite end of the same spectrum is family vacationing. To wit: Some parents reported that their families were attempting to “make up for vacations they had missed” during the first two years of the pandemic—“Some families took advantage of the fact that they felt comfortable again going on vacation,” said the elementary school principal—and chose to do so during the school year. (Yellow Springs News, 11/6/23)

- Finally today, a pair of stories from Dayton City Schools. The search for a permanent superintendent there continues apace, with a public meeting held earlier this week to allow community members to tell the search firm what they’re looking for in a new leader. A couple of elected school board members are quoted in this piece (mainly because the press were asked not to attend the breakout sessions), including this interesting “instruction” provided by one to her fellow concerned citizens: “If you put your child in our districts, what do you want from us? If you don’t put your children in our districts, why don’t you put them in there?” I for one am elated to hear an elected school board member fully recognizing their district as a choice—one among many—that parents can make. Love it! (Dayton Daily News, 11/7/23) Why does this make me so happy? Because Dayton City Schools-resident families must (as I must also) continually hear about a deeply dysfunctional operation whose highly-paid leaders and staffers regularly shoot their system in the foot and do not seem to have the capacity to dig out of entrenched structural deficiencies to focus on, say, improving academics or achieving basic operational stability. (Dayton Daily News, 11/8/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- I’m sure these are not new things, but I am equally sure I haven’t seen them covered quite so extensively in news reports before now. What am I talking about? Day-long jaunts where superintendents, teachers, and curriculum leaders from a group of schools go to another school to observe teaching and learning there. In this coverage from Lima City Schools, the event is termed “instructional rounds” and likened to the medical version where trainee doctors trail around after a veteran while examining and diagnosing real patients, then propose courses of treatment while the veteran evaluates their efforts for thoroughness and accuracy. (You remember it from numerous episodes of Scrubs, no doubt.) But ho-ho-hold up there, Newbie! Here’s how Jeff Talbert, Superintendent of Canton City Schools, describes it: “Today, we’re going to get to see how Lima is addressing their issues, how they are using their ‘problem of practice’ and strategies to do that. And as a collective group, I hope that one, we’re able to take away one or two things that we can take back to our districts to help us continue to improve in our practice, but we can leave a few nuggets here for Lima as they continue to go to work and move forward.” If you add that little “who’s really the expert?” mindset with a quick gander at both Lima’s and Canton’s most recent report cards, I think you’ll concur that this feels exactly nothing like medical rounds. Now does it, Barbie? (Lima News, 11/2/23)

- Everyone quoted in this story is thrilled about the $101K early literacy support grant recently won by the Jefferson County ESC in southern Ohio. It is aimed at helping preschoolers learn to read, featuring professional development programming for teachers in language acquisition, vocabulary building, letter recognition, and letter-sound recognition. It is also going to focus heavily on the kids’ parents and providing them what are termed “real-life literacy experiences to do at home” in support of their teachers’ efforts. I’m not sure at all what that might consist of, but it sure sounds good. (Steubenville Herald-Star, 11/3/23)

- Finally today, the editorial board of Cleveland.com has got vouchers on its collective mind. Personally, I get the impression its members are suspecting that near-universal eligibility is here to stay—grouchers and their lawyers notwithstanding—but that is only my impression. What they do talk about is the undeniable popularity of newly-accessible

vouchersprivate schools (fixed that for them) and what they see as the unfairness of voucher expansion to public schools along a number of dimensions. In light of this, the board suggests that public meetings—to be held in each of our 88 counties—are needed to hash out their concerns. To which I say: Be careful what you opine for, because the public may have some very different concerns they might like to opine about if given a chance. (Cleveland.com, 11/5/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Washington schools must now screen every elementary student for advanced education services, thanks to a law passed in May, which will better ensure equitable identification and access. To learn more about the history of this legislation, the efforts of its advocates, what it will mean for Washington children, and what lessons it may hold for lawmakers and organization in other states, I interviewed Austina De Bonte, President of the Washington Coalition for Gifted Education, whose efforts were integral to this noteworthy achievement.

De Bonte has been involved in gifted advocacy in Washington State for more than decade, beginning when she founded a parent advocacy group in her local district, the Northshore HiCap Parents Council. She’s also past president of NW Gifted Child Association and advisor to The G Word documentary.

Thanks for speaking with me, Austina. Washington just passed a law that makes gifted education more equitable and improves identification of gifted students by mandating that schools screen every child—a practice commonly known as universal screening. Will you explain why the law is so important and what it changes in the state?

This new law is a big deal. It requires all districts in the state to universally screen all students in a grade level for eligibility for Highly Capable programs. This must be done once in or before second grade and again in or before sixth grade. Universal screening may use existing test scores, but districts must gather at least two objective data points for each student. By prior state law, no single datapoint can disqualify a student. Furthermore, subjective datapoints, such as report card grades or teacher recommendations, can only be used to support a student’s qualification, never to disqualify. Any testing must happen during the regular school day (with exceptions for special situations allowed with parent permission).

Another feature of our new law is that many districts may not need to administer a new test if they already have sufficient recent scores on file for students, such as from SBA, iReady, STAR, MAP, etc. This makes the law so much more implementable in districts, with lower cost and logistical considerations, and is aligned with the latest research that really shows there is no benefit to using cognitive testing over achievement testing to identify students. Neither approach is perfect, actually, but what’s more important is that it’s done universally so every student is given the opportunity. Once you combine that universal opportunity with local norms, that’s when the real magic happens. A referral process must also remain available for students in grade levels that are not universally screened.

Additionally, the state must now publicly report the enrollment of each school district’s Highly Capable program, broken down by all the demographic categories that are tracked by the state. This will create much more visibility and accountability for districts to get serious about ensuring equitable access to Highly Capable programs for historically underrepresented groups, such as low-income students, multilingual students, students with disabilities (twice exceptional), highly mobile students, etc. Also the new law specifically mentions that districts may identify more than 5 percent of their student population; this was a frequent misunderstanding that has now been explicitly clarified.

How did this law come to be passed (i.e., what was behind proponents’ success)? And what role did the Washington Coalition for Gifted Education play?

Getting this law passed was a long, multi-year process. There were several prior attempts, with universal screening showing up in proposed bills as early as 2016. There were many years of committee hearings and legislator meetings to build awareness of this issue, to fine tune our messaging, and to work the bill through the many steps of the legislative process.

We really began to make more progress when the Coalition reorganized itself and its practices in 2021. We created regular meetings, had more open communication, welcomed some new board members, and acted more as a team. We also began building relationships with other—larger—organizations that have a lot more influence with the legislature than we do. All of this helped us become more proactive in anticipating how the legislature would respond to our efforts, and it has paid large dividends.

Getting other stakeholder groups aligned also turned out to be essential, especially the state teacher association, the state school board directors association, and the state parent teacher association. Despite some heartbreaking failures in prior years where it really felt like certain legislators might never come around in their thinking, ultimately the bill passed unanimously with full bipartisan support in every single committee vote, as well as on both the House and Senate floor, which was really remarkable.

One of the most important aspects of our advocacy was getting clear that the focus of this bill was fixing the very real and, in most communities, very visible equity problems in Highly Capable programs statewide. Owning that problem and coming in with real solutions that had been successfully piloted in numerous districts across the state was a big part of our successful messaging. This was a problem everyone could get behind fixing. Even if someone didn’t love the idea of Highly Capable programs, they could still get behind fixing the inequities.

You told me that rulemaking for the law is still ongoing. What’s at stake? What are the challenges? And again, how is the coalition planning to be involved?

The law passed by the legislature shows up in the Revised Code of Washington as it was written in the bill. However, every law has corresponding language in the Washington Administrative Code (WAC) that gives more detailed instructions on how that law is to be implemented and interpreted. In this case, that’s in the purview of the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). Modifying the existing WAC is a separate journey of working with stakeholders, drafting changes, and a months-long public comment process.

This is really only now getting underway in earnest, with OSPI engaging the state advisory board on Highly Capable programs and other stakeholders in providing suggestions and feedback that will ultimately be reflected in a first draft of proposed WAC changes sometime in the coming months. The Coalition gathered about twenty pages of feedback and suggestions over the summer that have already been fed into that process, but there are many other stakeholders, as well. The WAC will likely introduce several important nuances into the implementation of the law that will serve to strengthen the safeguards for equity, as well as provide a stronger advanced-education system for Highly Capable students statewide. The Washington Association for Educators of the Talented and Gifted just held its annual conference, and a major theme running through it was implementation of universal screening and local norms. This was really great to see.

The reality is that most districts are still working on getting into compliance with the new law. Although technically that law went into effect in July 2023, until the WAC is finalized, there will likely be some grace for districts to get into full compliance. Nothing happens quickly, sadly, but the train is moving in the right direction.

What advice would you give to other state-level advocates hoping to get similar bills passed in their legislatures? What are some of the keys to success for state-level advocacy for gifted students?

Patience was perhaps the hardest for our team of advocates. Our first failed bills failed largely because they bit off too much of the apple. Asking for universal screening, mandatory professional development, transportation, and a few other things all at the same time was too much to explain and to justify, and the price tag was too high. We found it really hard to set aside professional development in favor of focusing on equity through universal screening, but that was necessary to get to a tight, clear message that everyone could get behind, and that we could realistically get passed in the legislature.

We did have a partial success in 2017 and 2018 when a few important provisions did make it through the legislative process. These included prioritizing identification of low-income students, the use of local norms, not allowing a single data point to disqualify a student, requiring multiple pathways for qualification, and requiring nonverbal assessments when an assessment in the student’s native language is not available. It also included a provision that has turned out to be extremely impactful—which was stipulating that subjective measures such as teacher recommendations or report card grades can only be used as supportive data points, never to disqualify or screen a student out from further consideration. All of these provisions have become even more important now that universal screening has come into play with this year’s legislation, but they did have some positive impacts on their own.

It was also really important for advocates to get our arguments organized, and line up the research base, the local examples, and the hard numbers so that advocates were all using the same playbook and had rich talking points at their fingertips. Building a few one-pagers that could be shared as follow-up after a legislator meeting was a strong practice that I think really helped. You can see our three one-pagers, plus one created in collaboration with WA State PTA, on our website.

What’s next on the horizon in this work for you and for the coalition?

Our next advocacy priority is professional development. Despite the fact that Highly Capable programming has been a mandatory part of basic education in Washington State since 2014, there is zero requirement for any teacher or administrator to have any training in gifted education. Our regular pre-service teacher preparation programs don’t cover the topic, and while there is a gifted endorsement possible through Whitworth University, there’s not really any benefit to teachers for having that credential, so very few have sought it out. Neither is there any requirement for in-service education on Highly Capable programming, not even if a teacher is working in a self-contained Highly Capable program. So that is a big gap in our state right now, and impacts everything from the fidelity of program design at the administration level to the quality of advanced instruction being offered to students and to teachers’ awareness and support for students’ unique social and emotional needs.

Getting this done will require a tremendous amount of coalition building across multiple stakeholders to agree on a plan and, crucially, to allocate funding. That is bound to be a constraint. There are so many questions yet to answer. In the face of limited funds, do we, for example, focus professional learning on teachers, counselors, principals, or program administrators? Is it more important for all teachers to get a few hours of awareness training or for a few specialists to go deep? Is it more important to have robust pre-service training, or should we focus on in-service approaches? Ideally, of course, we would want it all, but that probably won’t be realistic. Models like those in Ohio and Texas that require a certain number of hours of continuing education for different types of teachers and administrators seem like a promising direction to consider, but it’s early days. We still have a lot of coalition building to do.

Stories featured in Ohio Charter News Weekly may require a paid subscription to read in full.

Fighting student absenteeism in Ohio

The Ohio Attendance Taskforce, whose members included DECA Superintendent and CEO Dave Taylor, last week released their findings and recommendations to fight chronic absenteeism among students across the state. Those recommendations focus on all players—schools, families, community organizations, and state policymakers—working together in a concerted effort to improve student attendance. You can read their full report here.

Enrollment growth continues

Charter school enrollment showed strong growth across the country in recent years, following a big boost in the wake of pandemic education disruption. This according to a new report from Moody’s Investors Service. Among other data points of interest: Florida, Arizona, and Idaho led the way in enrollment increases, with charters in the Sunshine State rising from 10.4 percent of public school enrollment in 2017 to 13.3 percent in 2022. Traditional district schools in those states showed a similar—and likely-related—decline in enrollment over the same time.

Legal wrangling resumes

Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond filed a lawsuit last week in the state Supreme Court to stop the establishment of what would be the first religiously-affiliated charter school in the country, arguing that the entity would violate both the state and U.S. constitutions. His action follows the Statewide Virtual Charter School Board’s approval of a contract to launch the St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual Charter School, sponsored by the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City.

More research worth reading

The National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice (REACH) released a first-of-its-kind look at how charter school regulation varies across states, and how those regulations relate to a variety of important outcomes. For just two examples: States with no charter caps, multiple charter authorizers, and more robust contract renewal standards have higher charter market shares. However, states with no charter caps also have lower student achievement growth. States with more equitable funding—that is, closer to parity with traditional districts—have higher student achievement growth. Fascinating stuff. You can read a policy brief version of the report here, and the technical report here.

Innovation vs. regulation

Student achievement is also the focus of one more new study to note this week, by authors including Jay Greene and Corey DeAngelis. They look at the regulatory environment in which various charters operate—quantifying a continuum of governmental oversight from loose to tight—as compared to the innovation level—quantified based on observations of pedagogy, curriculum, targeted student populations, setting, and themes—and seeing how the interplay of those two forces impact school structure and growth. The authors contend that tighter regulation stifles innovation, leading to a smaller charter sector narrowly focused on student achievement while looser regulation allows for a more robust sector with more innovative teaching and learning models available. The full report is here, while a somewhat contrary analysis of the methodology and findings is here.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

News stories featured in Gadfly Bites may require a paid subscription to read in full. Just sayin’.

- Ohio is front and center in this story about what is termed a “long, slow shift in formal authority” over education governance in many states “away from popular election and initially towards state boards of education, but more recently governors getting more directly involved.” Sadly, the discussion as to what has been fueling this shift focuses not on abysmal student achievement and stifling bureaucracy but on “hot button” issues and politics. You know what I mean. (Education Week, 11/2/23)

- I feel like this very small scale piece is actually related to the foregoing discussion, but it’s a thinker so stay with me. In it, we learn that some folks were really alarmed at the lowly one-star rating that Toledo City Schools earned on the early literacy component of their most recent state report card (at least they can’t get zero stars!) and are determined to spend some money to help students do better going forward. What’s the connection? The fact that the “concerned folks” are employees of a local law firm and that the funded “help for students” will be provided by a third party tutoring group. At least someone is reading and responding to report card data, I guess. But surely in a fully-functioning education governance model replete with thousands of skilled teaching professionals and awash in tens of millions of dollars—of the type supposedly nurtured and protected by the preferred elected state board model, as lionized above—the solution to low literacy ratings shouldn’t require lawyers paying out of their own pockets for outside tutoring services to support their neighbors’ children. Should it? (Toledo Blade, 11/1/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

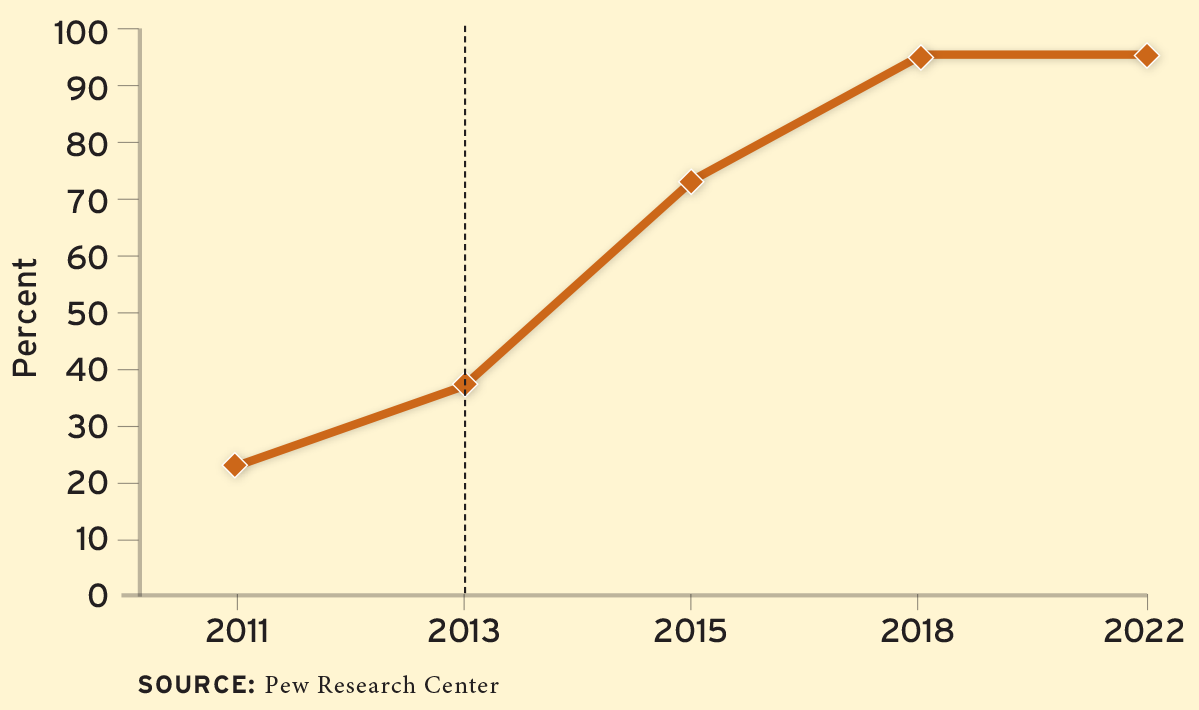

It’s understandable. The education world is awash in articles trying to figure out what artificial intelligence is going to mean for schools and students. But before we get too focused on the latest technological breakthrough, let’s not pretend that we have figured out how to cope with the previous one. Over the last decade, smartphones have become commonplace. Today, 95 percent of American teenagers have a supercomputer in their pocket.

Jonathan Haidt, Jean Twenge, and others have brought necessary attention to the likelihood that smartphones and social media are partly to blame for the teenage mental health epidemic gripping our nation. It’s not a watertight case, because it’s nearly impossible to prove a causal relationship with a phenomenon as ubiquitous as this one.

What scholars can say is that the sudden rise in teenage anxiety and depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide all happened at the same time that teenagers’ adoption of smartphones passed the 50 percent mark—around 2012 or 2013. They can also show that the children most likely to engage in heavy use of smartphones and social media—girls, especially liberal girls—also experienced the greatest increase in mental health challenges. And they can point to other countries that show similar patterns.

My purpose here is not to evaluate this evidence, though I generally agree with Haidt that we should adopt the precautionary principle and assume that phones and social media are likely doing real damage to our kids. Then we should act accordingly.

My immediate question, however, is whether phones and social media might also be behind the plateauing and decline of student achievement that we’ve seen in America, also starting around 2013, long before pandemic-era shutdowns sent test scores over a cliff.

I don’t believe this was the only cause of our achievement woes in the 2010s. As I’ve argued before, I believe the Great Recession was also to blame, both because of its impact on families’ home circumstances, and because of the sudden and significant budget cuts that followed in 2013 and 2014, especially in high-poverty schools. Kirabo Jackson has been particularly persuasive that these spending cuts had a measurable negative impact on achievement. Another potential factor was a shift away from school accountability; in 2012 the Obama administration softened the consequences for low test scores targeted by the No Child Left Behind Act. Then in 2015, and Congress replaced it with the Every Student Succeeds Act.

But I do think we need to take the smartphone hypothesis seriously. Especially because, unlike the Great Recession or the pandemic, these trends are not receding in the rearview mirror. Indeed, adolescent phone use continues to rise. If it is one reason that students aren’t learning as much as they did in the pre-smartphone era, that’s a problem we need to grapple with.

Figure 1. Share of U.S. teens age 12–17 with smartphones, 2011–22

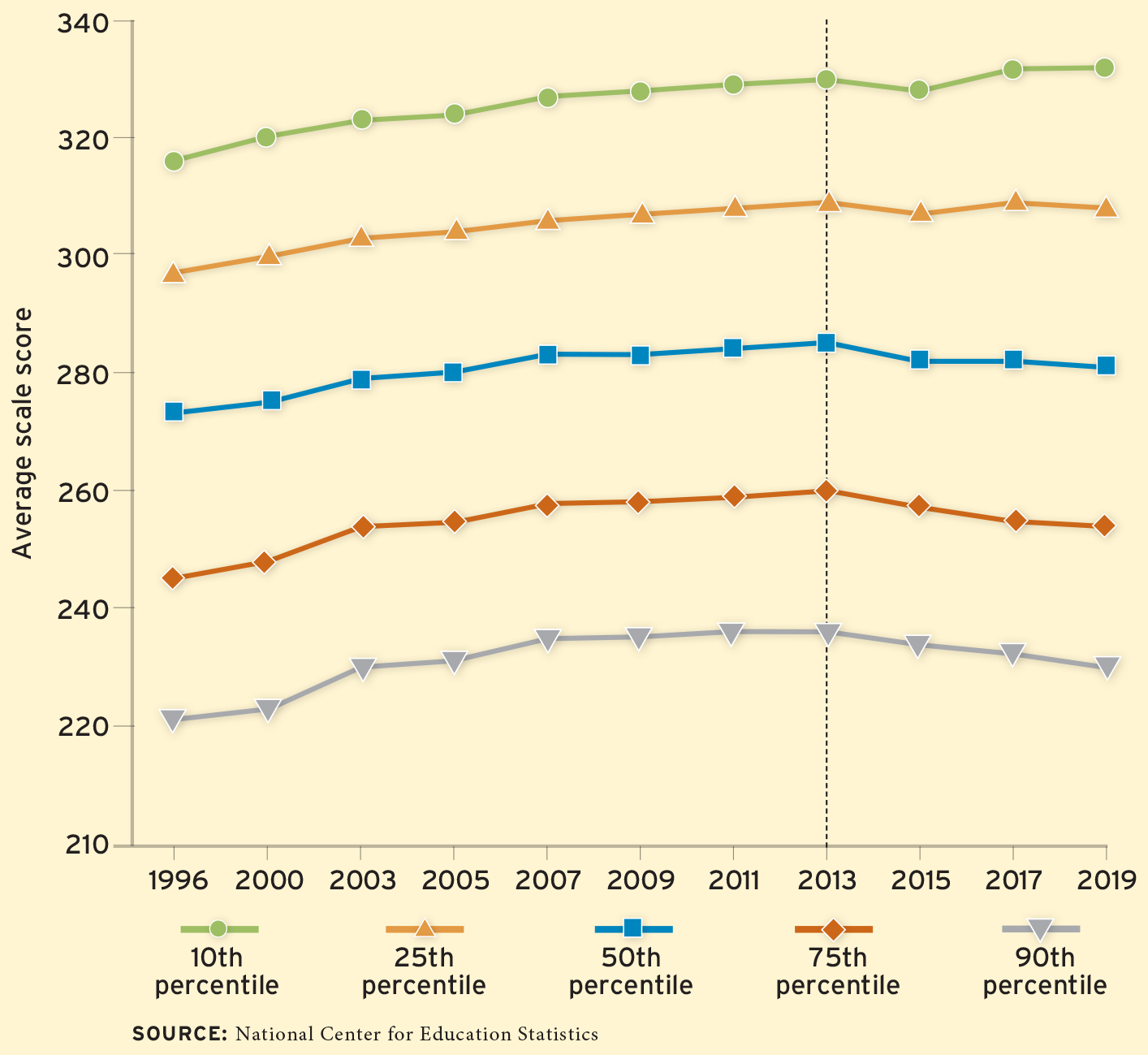

So what’s the evidence? First and foremost, as mentioned above, the timing lines up (see Figures 1 and 2). We see smartphone ownership really taking off among adolescents in middle and high school around 2013. That’s also when median achievement on the eighth-grade math test in the National Assessment on Educational Progress (NAEP) peaked. It’s fallen modestly ever since. For our lowest-performing students—those at the 10th and 25th percentiles—the declines were more dramatic.

Figure 2. Eight-grade math NAEP scores, 1996–2019

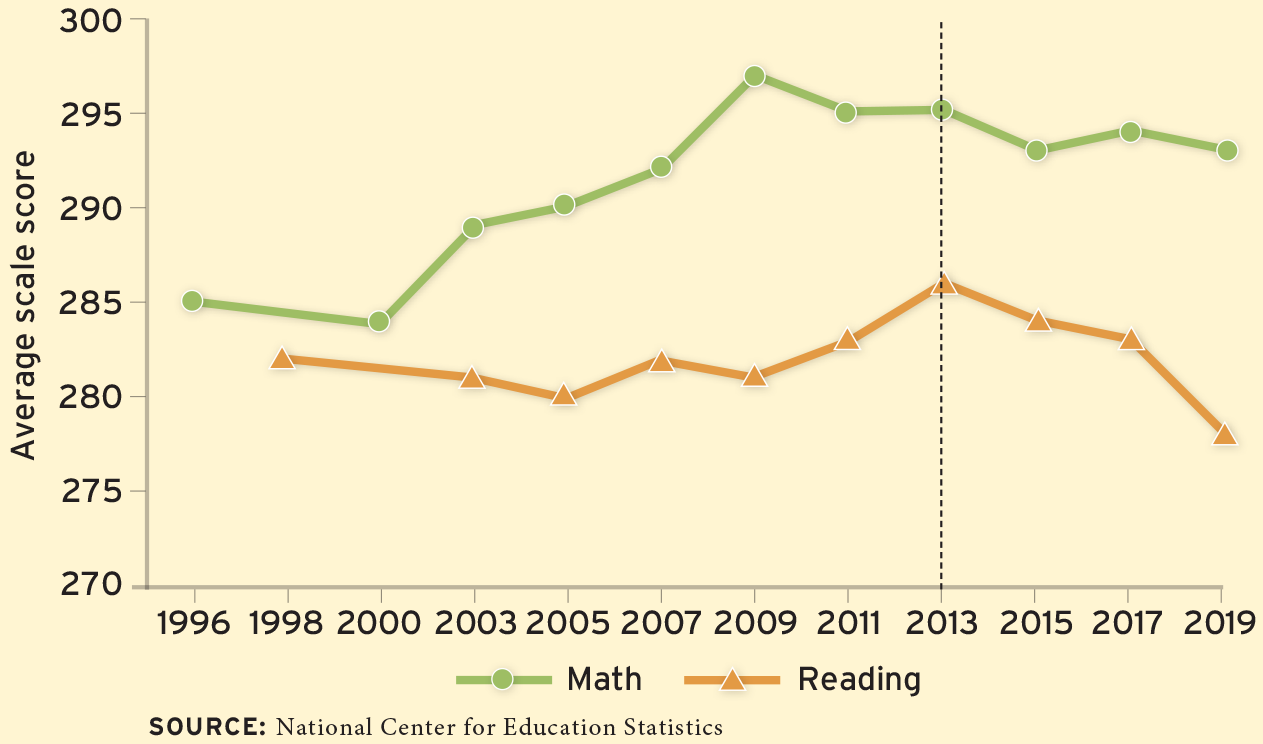

Another piece of evidence comes from Catholic schools, which serve as a plausible control group for the smartphone hypothesis (see Figure 3). Catholic-school students also take NAEP math and reading tests. But they are not directly impacted by changes in education policy such as the shifts in federal school-accountability rules or cuts in public-school spending. So if Catholic schoolkids also saw achievement declines around 2013, which in fact happened, especially in reading, that could be an indication that something outside education policy is to blame.

Figure 3. NAEP reading and math performance, 1996–2019

But there is also some conflicting evidence. The drops in achievement in the 2010s tended to be for our lowest-achieving students, who are disproportionately poor, Black, Hispanic, and male. And yet, as we know from the studies that Haidt and others point to, phone and social media use was most concentrated among middle-class girls (at least initially). So that doesn’t match up.

Before I conclude with the obligatory call for more research, it’s worth pondering what mechanisms could link smartphone and social media use to lower student achievement. Most obvious are problems around attention, as students’ brains adapt to the rush from “likes,” YouTube videos, TikToks, and other platforms, and then struggle to listen to (much less read) slower-moving and less-vivid presentations, such as the ones they are likely to encounter in class and homework. (Our poor teachers!) Or it could be phones’ impact on mental health; it’s hard to learn when you’re anxious or depressed.

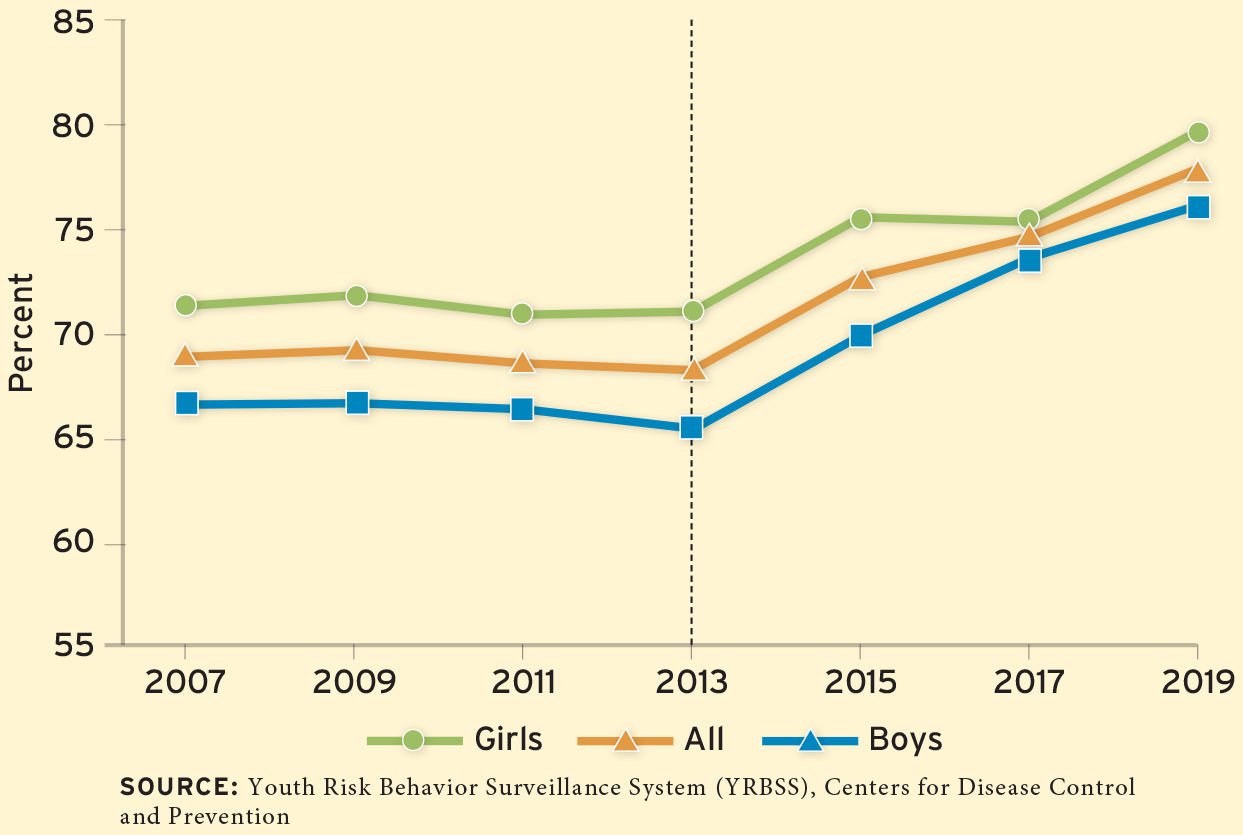

There’s also the issue of sleep (see Figure 4). This is cited in the mental health literature, too, as we know that kids sleep less today than before phones and social media entered the scene, and we also know that there’s a relationship between less sleep and poor mental health.

Figure 4. Adolescents sleeping less than eight hours per night

But so too is there a relationship between less sleep and less student learning. After all, sleep is when the brain works much of its magic, forming connections and cementing ideas in long-term memory. Plus, it’s hard to learn when you’re tired, and it’s really hard to learn when you stay home from school because you have been up much of the night. So there is an angle here that also connects with our chronic absenteeism crisis.

What to make of all of this? If we return to the precautionary principle, the least we can do is try to encourage parents to curb their tweens’ and teens’ phone and social media use. Educators can do their part by setting and enforcing classroom rules that phones be turned off or at least stowed away, unless there’s a compelling instructional reason to use them—though that is admittedly an uphill battle. Abolition is likely impossible, though some legislative proposals to make it harder for kids to access social media apps until they are sixteen might help. But schools could certainly encourage parents to limit screen time to a reasonable number of hours per day, be much tougher about earlier bedtimes, and require kids to dock their phones outside their bedroom during sleeping hours. There’s a strong foundation of research to back up any effort to protect and promote students’ sleep, which may help ease some uncomfortable conversations.

Indeed, more sleep might be the killer app that could make a huge difference—both for students’ academic achievement and mental health. It’s a good reminder that as we contemplate the future impact of AI on schools and society, what likely matters most aren’t the machines we use but the attention we give to our children’s timeless human needs.

Editor's note: This was first published by Education Next, which also created the figures that are reproduced here.

Welcome to the latest installment of the Regulation Wars, a long-running family quarrel that centers on the perceived tensions between two of the charter school movement’s founding principles: innovation and execution (or, if you prefer, autonomy and accountability).

Advocates of the former worry that a single-minded focus on the latter will stifle new and potentially fruitful ideas and practices. So, in an effort to shed additional light on the subject, a new study by Ian Kingsbury, Jay Greene, and Corey DeAngelis tries to quantify “innovation” and understand how it relates to policymakers’ efforts to ensure a morally acceptable level of execution—that is, to regulation, mostly in the name of accountability. More specifically, the study focuses on the relationship between states’ widely varying regulatory environments and the ostensibly innovative characteristics of the 1,438 charter schools that opened in the United States between 2015 and 2017.

To quantify regulation, the authors rely on the scores that the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) gave to states between 2014 and 2016, which range from 0 to 33 (with a higher score signifying a tighter approach). To quantify innovation, they first examined individual schools’ websites and coded them to see how they varied along five dimensions: pedagogy, curriculum, populations targeted, setting, and themes. They then assigned each identified characteristic a point value “equivalent to the inverse of its [national] prevalence.” (In other words, they gave more points to schools that were more unusual.) And finally, they added up the points that individual charter schools were awarded for each characteristic/dimension.

Based on the resulting totals, the authors’ estimate that a 1-point increase in a state’s NACSA score was associated with a 0.014 standard deviation decrease in the innovativeness of the average charter school that opened within its boundaries. Similarly, they find a negative relationship between a state’s NACSA score and the innovativeness of the average school’s “pedagogy,” “setting,” and “theme.” Yet, as they acknowledge, “the abstract nature of the total innovation score and components makes it difficult to interpret results.” So, to concretize things, they also consider the relationship between regulation and the twenty-four characteristics that are the basis for the five dimensions of “innovation.” Of these, six are significantly related to regulation. For example, states that take a tighter approach to regulation have fewer schools in “virtual” and “hybrid” settings, as well as fewer with “experiential” pedagogies.

The existence of something akin to these more granular relationships is fairly intuitive. After all, even most accountability hawks acknowledge that there are trade-offs. Insofar as authorizers prioritize test-based academic growth—which they should, given the strong relationship between short-term test score gains and positive long-term student outcomes—that necessarily rubs up against a laissez-faire, anything-goes embrace of “innovation.” Still, the mere likelihood of such a tradeoff does not imply that it is troublingly severe, that the authors have succeeded in quantifying it, or that sober-minded education policymakers should spend a lot of time worrying about it in an era of widespread learning loss and justified alarm about the trajectory of national achievement trends.

From a purely normative perspective, an obvious problem with the authors’ approach is that it is content neutral. So, for example, a school that was grounded in Satan Worship would count as highly innovative (provided it didn’t start a movement), as would one that imparted no knowledge whatsoever (as seems to be the case for many virtual schools). Moreover, if the concern is really with innovation, at least as traditionally understood, then timing is an issue, as is clear from the authors’ self-generated list of ostensibly innovative characteristics, which includes longstanding programs such as Core Knowledge (est. 1986), Waldorf (1919), and Montessori (1907), not to mention “single-sex” education (Harvard, circa 1636) and “project-based” learning (the Pleistocene).

As those examples suggest, what the authors’ measure actually captures is more akin to “programmatic diversity” than “innovation.” Except that even “diversity” is being generous, since what the measure really captures is how similar a particular state’s charter sector is to the national charter sector (rather than how many different types of schools a state’s charter sector includes). Which simply isn’t the same thing as diversity or innovation, no matter how much the authors may want it to be.

For obvious reasons, the dissimilarity between a state’s charter sector and the rest of the charter school movement could be related to the types of students it serves. Yet, as noted, a school’s “targeted population” is itself a dimension of innovation and/or diversity, meaning that states with disproportionate numbers of students who are “disabled” or “at risk of dropping out” are likely rewarded or penalized insofar as their charter sectors are representative.

Similarly, it seems obvious that charters in rural states are more likely to have virtual and hybrid schools than those in more urbanized states, and that more rural states (which tend to be redder) may be likelier to take a hands-off approach to regulation. So even if one grants that more virtual schools are a good thing (and, to be clear, one does not), it’s not obvious that tighter regulation is the cause of their relative scarcity in places like New Jersey. In other words, in addition to being fundamentally correlational, many of the relationships the study uncovers are plausibly explained by factors that states cannot control and that have nothing to do with regulation.

All of which makes it hard to swallow the authors’ claim in a recent National Review article that “we know heavy charter regulation has this negative effect on diversity and innovation in the charter sector because we actually measured it in our new peer-reviewed study.”

No, we don’t. No, they didn’t. And the mere fact that a study is “peer reviewed” doesn’t mean it should be taken seriously.

Yes, one of the hopes was that charters would be innovative, and some of them are. But with or without those burdensome regs, genuinely useful innovations seem to be a rarity in K–12 education, which is why the charter school movement has often disappointed on that score and the focus has understandably turned to execution, where there is far more rigorous evidence of their continuing success.

Maybe it’s premature for an election that’s still a year away, and perhaps it’s archaic to expect to find any serious discussion of issues and policies in candidates’ campaign websites. Old-fashioned plodder that I am, however, I went foraging on those websites to see what I could find about their policy positions on education.

I started with the two “official” Biden re-election campaign sites and came up completely dry—dry on issues in general, not just education. They’re devoted to fund-raising and staff recruitment. No doubt the powers that be in the Biden camp prefer to let the President’s actions and proposals signal what he would do during a second term, at least for the time being.

Turning to the Republican side, with Mike Pence now out, I settled for Politico’s judgment that six GOP contenders remain, in some sense, plausible. So that’s where I went hunting. It was not a totally fruitless quest, but it wasn’t very rewarding, either. Here’s the short version:

The Trump website has a lot to say on education.

Tim Scott also has a lot to say.

Vivek Ramaswamy has a few one-liners.

The others—DeSantis, Haley, Christie—are almost devoid of substance at the campaign website level, but they’re all governors or ex-governors, so it’s not hard to track down information about their education track records.

Does it matter? Read on—they’re in the same order as above—and see what you think.

Donald Trump:

One of Trump’s campaign websites states his positions and plans on fifteen major issues. Education appears under the heading “Protect Parents’ Rights.” Here’s the entirety of it:

President Donald J. Trump fought tirelessly to expand charter schools and school choice for America’s children. He secured permanent funding for Historically Black Colleges and Universities and protected free speech on college campuses. Now, Joe Biden and the radical left are using the public school system to push their perverse sexual, racial, and political material on our youth. President Trump will cut federal funding for any school or program pushing Critical Race Theory or gender ideology on our children. His administration will open Civil Rights investigations into any school district that has engaged in race-based discrimination. President Trump will veto the sinister effort to weaponize civics education, keep men out of women’s sports, and create a credentialing body to certify teachers who embrace patriotic values. President Trump will reward states and school districts that abolish teacher tenure for grades K–12 and adopt Merit Pay, cut the number of school administrators, adopt a Parental Bill of Rights, and implement the direct election of school principals by the parents.

Tim Scott:

Senator Scott’s website is by far the most detailed on a bunch of issues, including an extensive section on education, half of which recounts his record in Congress. Here’s (all of) what’s there:

Education, Not Indoctrination

“I have lived the truth that education is the closest thing to magic in America. But today, the far left has us retreating away from excellence in our schools. Extreme liberals are letting Big Labor bosses trap millions of kids in failing systems. They’re replacing education with indoctrination.”

America’s children should be learning ABCs, not CRT. The radical Left wants to indoctrinate our children, not educate them. We will fight to ensure that America’s kids are learning how to read and write, not about gender transition and sexual identity. We must demand excellence in our schools, which means giving every family a choice, every parent a voice, and every child a chance.

- Defend parental rights by giving every family the power and resources they need to decide their child’s education and future.

- Demand transparency in the classroom so parents are informed as to what their children learn in school.

- Expand opportunities for all children by embracing education freedom and empowering parents, which will allow millions of children to unlock their God-given potential.

A Proven Record:

- The CHOICE Act: Ensures parents have the tools to find a school that can effectively serve their child’s needs and grants flexibility and support to parents with disabled children.

- Training America’s Workforce Act: Empower apprenticeship programs because every child deserves the opportunity to achieve their version of the American Dream.

- Kids in Classes Act: Big Labor Bosses have kept children out of classrooms, so this legislation would allow families to put unused Title I funds toward further choices for in-person education.

- Educational Choice for Children Act: Provides $10 billion in annual tax credits for Scholarship Grant Organizations.

- PROTECT Kids Act: Cut off federal funding from any school that allows students to change their pronouns, gender markers, or sex-based accommodations including locker rooms and bathrooms, without their parents’ consent.

Note before moving on that both Trump and Scott pack a lot of substance into relatively few words. None of it is developed in detail—and some seems beyond the reach of anyone sitting at the Resolute desk. But it’s worth coming back one day for some serious unpacking of what they, as President, might actually try to do in education.

Vivek Ramaswamy:

His campaign website offers twenty-five one-liner “policy commitments to take America First further than Trump.” The two that (sort of) bear on education say this: “Incentivize trade schools over hollow college degrees (sorry, gender studies majors)” and “Shut down toxic government agencies: Dept of Education, FBI, IRS, and more (and rebuild from scratch when required).” Period.

Ron DeSantis:

Nothing about issues is printed on his confusing and shape-shifting website. A few video clips show him speaking briefly about education. But his time as governor of Florida has built quite a record, much of it in the realm of “culture wars.” USA Today offered a decent summary.

Nikki Haley:

Her campaign website is regrettably silent on issues. But she, too, was a governor (2011–17) and built an education track record. More immediately, a Spectrum News transcript of a recent New Hampshire campaign forum offers a summary of what she says she would focus on in education if elected president.

Chris Christie:

You’ll find nothing on issues on the campaign website, though there are a bunch of videos. But he, too, racked up a considerable record on education as governor of New Jersey (2010–18), which may prefigure what he might seek to encourage in this realm if he were president.

Campaign websites, like party platforms, won’t likely influence the choices of many voters, whether in primaries on the general election. But insofar as they offer clues as to what a candidate might actually do once in office, they bear watching. So I’ll be back with more, including my take on the Trump and Scott assertions.