For more than two decades, report cards have offered Ohioans an annual check on the quality of public schools. They have strived to ensure that schools maintain high expectations for all students, to provide parents with a clear signal when standards are not being met, and to identify high-performing schools whose practices are worth emulating.

The current iteration of the report card uses intuitive letter grades—a reporting system that most Ohioans are accustomed to and support—and includes a user-friendly overall rating that summarizes school performance. In recent years, state policymakers have added new markers of success, including high school students’ post-secondary readiness and young children’s ability to read fluently.

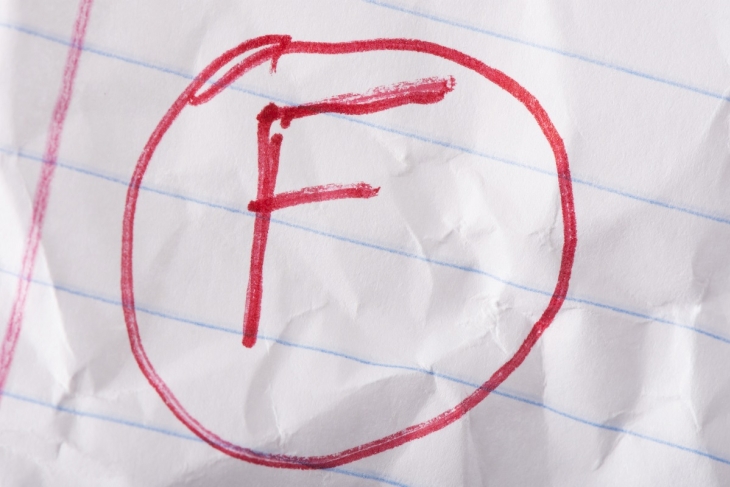

While the current model can be improved, an ill-advised piece of House legislation (House Bill 200) goes in the wrong direction. It would gut the state report card—rendering it utterly meaningless—and cloak what’s happening in local schools. In short, the proposal would take Ohio back to the dark ages when student outcomes didn’t matter and results could be swept under the rug.

What does the bill do and why is it so bad? The bill:

- Uses incoherent rating labels. House Bill 200 replaces A–F letter grades with a six-category descriptive system for each report card measure. From highest to lowest, the labels are as follows: significantly exceeds expectations, exceeds expectations, meets expectations, making substantial progress toward expectations, making moderate progress toward expectations, and in need of support. These vague, jumbled labels will mean little to Ohio parents and citizens. What exactly does it mean to “exceed expectations” or “make progress” toward them? Can you guess to which letter grades those terms might correspond to? Whose expectations are they anyways? Worse yet, some of the labels will be downright misleading. There will be schools deemed to be “making substantial progress toward expectations”—equivalent to a D (or C?) rating—whose performance declines in a certain report card component (e.g., their achievement levels fall from the prior year). Lastly, the “in need of support” label is a euphemism that doesn’t raise red flags for parents or communities.

- Eliminates the user-friendly overall rating. The House bill scraps the overall rating that combines the various dimensions of the report card into a bottom-line assessment of school quality. It’s akin to a final GPA that sums up student performance across various subjects or to a credit rating that communicates risk to potential lenders. Dropping the overall rating, however, deprives parents of a prominent, user-friendly summary. Even worse, the lack of an overall rating allows for “cherry picking” one or two component ratings that support a specific narrative—either good or bad. An overall rating prevents such efforts by evening out the strengths and weakness of a school and offers a more comprehensive picture of school quality.

- Dumps a crucial measure of post-secondary readiness. First appearing as a graded component in 2015, the prepared for success dimension of the report card offers insight into students’ readiness for higher education and rewarding careers. Readiness indicators include remediation-free scores on college entrance exams, industry credentials, and passing scores on AP or IB exams. Importantly, such indicators go above and beyond basic high school graduation requirements and state tests, thus offering a look at whether students are meeting bona fide readiness targets. Given the ongoing need to prepare more young people for higher education and technical careers, it’s odd to see House lawmakers seeking to scrap this report card component. While the design of the component could use some improvements and a fairer grading scale, it remains a vital piece of today’s report card because it encourages schools to challenge students to meet more than bare minimum standards.

- Suppresses the performance of disadvantaged students. The state’s gap closing component ensures that less advantaged students—i.e., those who are economically disadvantaged, in special education, and/or English learners—don’t fall through the cracks. House Bill 200 at least keeps the component, but makes two changes that would soften accountability for these vulnerable student groups. First, it continues a misguided either-or approach to achievement and growth. Whichever measure—either a subgroup’s performance index or value-added score—yields a higher rating is the one that applies. For example, a school’s economically disadvantaged students might post satisfactory value-added scores but still fail to make meaningful progress toward proficiency. Under HB 200, the latter would be completely ignored in favor of the higher score.[1] Second, HB 200 increases the minimum “n-size” that schools must have in a subgroup before they are held accountable for their results in gap closing. Under current policy, which was developed through the state’s ESSA planning process, schools must have at least fifteen students in a subgroup. HB 200 raises that to twenty. As a result of this change, thousands of needy students will vanish from the subgroup accountability system.

- Weakens accountability for early literacy. Research has shown that children struggling to read are more likely to face academic difficulties later in life. Over the past decade, Ohio policymakers have enacted a number of policies aimed at boosting early literacy, including the creation of a K–3 reading report card component. Unfortunately, HB 200 would weaken this measure, as well. First, it would rely on promotional rates used for the Third Grade Reading Guarantee. The dirty little secret about these rates is that they exclude students who aren’t subject to retention, include promotions via alternative non-state testing options, and are based on a lower bar than the proficiency standard. As a result of these policies, the statewide promotional rate was a whopping 95 percent in 2018–19 even though the third-grade ELA proficiency rate was 67 percent. Talk about hiding the ball. Also disturbing is HB 200’s proposal to exclude mobile students from promotional rates; only students who have been in the same district or school in Kindergarten through third grade would count. Do mobile students simply not matter? Taken together, these policy decisions will produce inflated literacy ratings, ease the pressure on schools to help children read, and sweep any deficiencies under the rug.

Report cards are a balancing act. They must be fair to schools, offering an accurate and evenhanded assessment of academic performance. But they must also be fair to students—who deserve a report card system that challenges schools to meet their needs—and to parents and citizens who deserve clear and honest information about school quality. Ultimately, HB 200 veers too far in trying to meet the demands of school systems, which have an interest in a report card that churns out crowd-pleasing results—one that only captures “the great work being done in Ohio’s schools,” as the head of the state superintendents association recently put it. Such a system might avoid controversy, but it’s also a one-sided picture that ignores the interests of students, families, and taxpayers. As state lawmakers consider HB 200, they need to remember that report cards should be an honest assessment of performance, not simply a cheerleading exercise.

[1] HB 200 also takes a wrong either-or approach to value-added growth scores within the Progress component. The bill requires the use of either the three-year average score or the most current year score, whichever is higher.