Conferred by businesses, industry groups, and state certifying entities, industry-recognized credentials (IRCs) are intended to signal that students have mastered specific workplace knowledge and skills.

This first-of-its-kind study assesses the impact of specific IRCs earned in high school on various employment and postsecondary outcomes for students who do and do not attend college. The findings can help education leaders and policymakers improve CTE and IRC opportunities in order to boost student success in the labor market.

To read the full report and its implications for educational leaders and policymakers, scroll down or download the PDF (which includes the appendices).

Foreword

By Amber M. Northern and Michael J. Petrilli

The cost of groceries, cars, plane tickets— it seems like everything is going up these days. What's not? The number of teenagers going to college. Recent statistics show that 685,000 fewer students were enrolled in undergraduate programs (both community colleges and four- year institutions) in spring 2022 than the previous spring. That’s a drop of 4.1 percent—steeper than the 3.5 percent decline the previous spring. To date, the college student body has shrunk by nearly 1.4 million or 9.4 percent during the pandemic.

One reason is that younger Americans, for better or worse, are starting to question the value of college. Among those with a bachelor’s degree or more, just 56 percent under age thirty think the benefits of their education exceed the cost. That compares with 82 percent of those age sixty or over.

While postsecondary education obviously remains valuable for students’ career prospects, escalating tuition costs—coupled with many young people saying they aren't learning job-ready skills—means that we need to do a much better job preparing both students who choose to go straight into the labor market after high school and those headed to college. One way that high schools can respond to increasing demand for career preparation is by helping their students attain industry-recognized credentials (IRCs).

These are credentials conferred by businesses, industry groups, or state certifying entities to individuals who demonstrate a sufficient level of knowledge and skills in a particular domain, often through one or more assessments. For instance, the American Welding Society (AWS) issues several different types of welding certifications pertaining to inspection, engineering, education, and sales.

Students earn IRCs most often through career and technical education (CTE), including “concentrating” in several related CTE courses. Some want an IRC, or at least its content, for personal reasons—so they can repair their own car, cook for their family, or even flip houses one day. Others see a high school IRC as part of a stack of credentials to be accumulated, a stack that may include some (or a lot of) college and additional vocational and technical instruction.

But the most straightforward reason for a high school IRC is to advance one’s prospects in the workforce. Yet we know almost nothing about whether IRCs better equip high school graduates to gain employment and earn a living wage. Neither do we know whether IRCs earned during high school make it likelier that students will build upon them when choosing college majors.

Texas has taken this seriously. In 2017, the Lone Star legislature directed the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to publish a list of approved IRCs that are recognized and valued by employers and to factor students’ receipt of such IRCs into the state’s school accountability system. After soliciting extensive feedback from employers, workforce boards, and colleges, the TEA constructed a list that consisted of credentials (presumably) aligned with high-wage, in-demand occupations that are to be periodically reevaluated. Students who complete an approved IRC in Texas are now deemed to be college, career, and military ready (CCMR) in the state school accountability ratings.

Now we can see how young Texans with IRCs fare the first year out of high school and can compare them with similar peers who lack IRCs. To our good fortune, Matt Giani, director of research and data science at the University of Texas–Austin, was keen to conduct the study. As the supervisor of research and evaluation activities for OnRamps and Texas OnCourse (two programs meant to augment the pipeline of diverse Texas students attending selective colleges), Professor Giani has a history of successful projects that link Texas K–12 data to postsecondary and workforce outcomes.

Now we can see how young Texans with IRCs fare the first year out of high school and can compare them with similar peers who lack IRCs. To our good fortune, Matt Giani, director of research and data science at the University of Texas–Austin, was keen to conduct the study. As the supervisor of research and evaluation activities for OnRamps and Texas OnCourse (two programs meant to augment the pipeline of diverse Texas students attending selective colleges), Professor Giani has a history of successful projects that link Texas K–12 data to postsecondary and workforce outcomes.

We won’t restate his key findings here, but we can simply say that we agree with Dr. Giani’s conclusion that high school IRCs are a net positive for students who earn them but are not game changers. Hence our lingering question: How else can we transform the high school experience for students so as to significantly boost their wages and career prospects once they are in the workforce?

Here are four ideas:

1. Stress the key roles of high schools—and middle schools, too—in helping students figure out their career interests and aptitudes.

If we really want young people to make the most of their last four years in K–12 education, we need high schools to help them align their aptitudes with their interests. This means using middle school to commence career exploration. Grades 5–8 are a good time for students to learn about different career options through exploratory and introductory CTE courses and to develop a plan for reaching future goals1—perhaps gaining some exposure to coding, robotics, digital media, film production, and so on, all while also learning the essentials of a quality core curriculum.

Nobody is saying that twelve-year-olds should make a major life decision, but one way to help students learn about their options is to identify not only what they are interested in but also what they are good at. One of us recently wrote about a new generation of aptitude assessments for middle and high schools where students complete a series of activities (or “brain games”) that “allow them to see career paths for themselves that line up with their aptitudes and are free of the race, class, and gender biases that tended to plague old-style interest inventories.” Such assessments focus on potential, not achievement, so “the results often tell kids about strengths in areas the children had thought were weaknesses.”

Strategies like these can open up new career paths for students to explore in middle school, as well as get them thinking sooner about which paths they want to take more seriously in high school. If we wait until students are juniors or seniors before we attempt to help them prepare for the world of work, we’ve done them a disservice.

2. Embrace approaches that are much more ambitious than IRCs, such as serious youth apprenticeship programs.

Exposure to the workforce in high school has generally benefitted students. For instance, prior research found that summer employment helps improve school outcomes for low-income youth. What’s more, students who work ten or so hours a week during the school year—even as early as grade 9—experience a boost in test scores and in the amount of schooling they complete. Thankfully, more states are calling for work-based learning programs which, says Jobs for the Future, provide “real-world opportunities to apply the lessons learned in classroom settings, build professional networks, earn money while they learn, and get a head start on the road to a career.”

It makes sense, then, that the culminating high school experience for students choosing to go straight into the workforce should be an in-person, hands-on experience in a field in which the student has demonstrated aptitude—ideally by concentrating in a series of sequential CTE courses and earning an IRC in the same industry while engaging in a real-world apprenticeship (or at least the start of one). Such an approach must be high-quality and equitable; hence it’s encouraging that our results show that career and technical programs that lead to IRCs do not constitute a lower educational “track.” Still, given historical concerns about adults doing the steering, these choices must also be student initiated, which leaves open the possibility that many of these students will choose to return to school at a later point in time.

We can imagine a middle or high school continuum that moves students along a series of options ranging from less intensive and less transformational to more intensive and more transformational, such as the following:

1. Career exploration

2. CTE course taking

3. CTE concentration

4. IRCs (on top of CTE concentration)

5. Youth apprenticeships

Several states have recently gotten serious about providing high-quality apprenticeships as a capstone experience for young people. Research on them is growing, with recent studies finding that apprentices earned significantly more than similar peers who completed only the accompanying course. Other studies find that apprenticeships boost employment and “decrease idleness” among male high school graduates who don’t enroll in college.

CareerWise Colorado, for instance, operates a program in which participants split their time between high school and the workplace. Apprentices begin in grade 11 and finish in their thirteenth year, yielding both an IRC and a chance to earn debt-free college credit. Louisiana's Fast Forward program also gives students a leg up on their career. And Governor Janet Mills of Maine recently announced $12.3 million in grants to expand apprenticeship and pre- apprenticeship programs across her state.

What these and similar programs recognize is that high schools must free up significant time in students’ schedules to accommodate apprenticeships, which almost surely means expanding the high school day, making generous use of dual-enrollment courses, or foregoing some traditional academic requirements.

Louisiana adopted a couple of these approaches in their Fast Forward program:

As part of the Fast Forward program, students spend the majority of grades 9 and 10 on the high school campus, earning core graduation requirements.

Once they reach grades 11 and 12, students spend the majority of their time on the postsecondary campus or a satellite location while dually enrolled in courses. This ensures students complete their graduation requirements while also earning an associate’s degree or earning on-the-job experience participating in a state- registered pre-apprenticeship/apprenticeship.

Once they reach grades 11 and 12, students spend the majority of their time on the postsecondary campus or a satellite location while dually enrolled in courses. This ensures students complete their graduation requirements while also earning an associate’s degree or earning on-the-job experience participating in a state- registered pre-apprenticeship/apprenticeship.

3. Encourage stackable credentials.

A great many IRCs worth getting—because they relate to good jobs and authentic careers—cannot be completed while in high school. The high school version is a solid stepping stone, however, which is why the idea of stackable credentials needs to be taken seriously. As the term implies, these credentials build on one another, often embedding certifications that help students quickly and cost-effectively gain skills that lead to employment.

Stackable credentials can be more or less useful, however, as the skills and knowledge earned through some IRCs are more tightly linked to particular industries. The IT and Health Science fields tend to be more amenable to stacking, while those in Retail Trade and Manufacturing are less so. For example, in the field of radiology, students might first gain a limited medical radiologic technologist certificate (LMRT), then a radiologic technology associate degree (RT), and finally a radiologic science management bachelor’s degree.2

A better understanding of the fields that already boast fruitful stackable certifications would benefit workers and employers alike. So would development of more such stacks in high-demand fields. Indeed, recent research in Virginia showed how stacking can affect one’s labor-market outcomes. Adults who completed a stacked credential were four percentage points more likely to be employed than non-stackers and earned about $570 more each quarter.

4. Make state accountability systems more selective regarding which high school IRCs count in their college- and career-ready indices.

More than half of states report including K–12 IRC attainment measures in their accountability systems.3 But many of them are awfully lenient in terms of which credentials count as part of college and career readiness.

We need truth in advertising. A certification in a popular desktop program is not the same as one that combines hands-on industry-specific skills and tech-specific software. We might benefit from a credentialing hierarchy, perhaps one that distinguishes among “building block” or general readiness skills (such as basic first aid, financial literacy, and general safety), stackable certifications, and capstone credentials that demonstrate mastery or advance careers.

To wit, Credentials Matter looked at thirty states and found that Microsoft Office Specialist was the most commonly earned credential (it was second in popularity in this report). But they termed it a “nice to have” because “overall, employers do not [specifically] request credentials to prove software competence, and most people learn and validate these in-demand skills through other means.” Further, “states, educators, and employers [need] to help students prioritize the credentials that will carry the most value in the workforce given the time and resource constraints inherent in schools.”

We agree. General skills are important to have but do not deserve much weight in a statewide accountability system that prizes high-skill, high-wage occupations.4 States need to be more discerning regarding what counts and what doesn’t.

We agree. General skills are important to have but do not deserve much weight in a statewide accountability system that prizes high-skill, high-wage occupations.4 States need to be more discerning regarding what counts and what doesn’t.

**********

This first-of-its-kind report gives us an in-depth look into the value of IRCs in a state that takes them seriously and has invested in them. We hope that other studies will trace the impact of IRCs in other states and for longer timeframes.

In the meantime, we very much need to distinguish between two purposes of IRCs: the “must haves” and the “nice to haves.” As for the latter, yes, let’s leave room for students to obtain these credentials because they enjoy the work and see real-life value in them. It’s one thing to take some CTE courses while always planning to go to college anyway, and it’s fine to get an IRC to pursue an interest unrelated to college or career plans. But let’s not forget that these are industry-recognized credentials. The “must have” is to promote job success. Yet the kind of IRCs you can earn while in high school are often just the tip of the iceberg.5 That’s because most high school IRCs need to be linked to meaningful CTE programs that include high-quality apprenticeship and internship programs and myriad other opportunities to gain additional credentials, often including further study of some kind after graduating.

There’s not enough of that happening. That means that policymakers may too readily judge the effectiveness of high schools not on their adoption of high-quality career and workforce pathways but on IRC programs and attainments that in and of themselves don’t add great value to many students’ lives. If we’re serious about helping students to succeed on the job, that needs to change.

Introduction

Introduction

Parents, policymakers, and much of the public worry that today’s U.S. education system is not adequately preparing youth for life after high school. For decades, one of the most prominent approaches for ensuring that students are ready for the labor market has been providing them with career and technical education (CTE), once known as vocational education. Yet historical research finds that vocational education failed to live up to its promise: it stratified educational opportunity by race and class,6reduced students’ likelihood of attending college,7 diverted students from four-year to two-year colleges, 8and transitioned students into careers with limited opportunities for social mobility.9 These findings likely contributed to the decline in CTE course taking between 1990s and early 2010s.10

More recent studies have found less evidence of racial and socioeconomic disparities between students who complete a series of CTE courses (“concentrators”) and those who do not11and more positive relationships between CTE and students’ postsecondary outcomes.12 Coinciding with Congress’s passage of the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (“Perkins V”) in 2018, there has been a resurgence in research, policy activity, and school reform related to CTE in recent years: in 2019 alone, twenty-eight states passed legislation related to career tech.13

An increasingly prominent strategy for ensuring that CTE programs develop knowledge and skills that are actually aligned to the workplace is to provide students with opportunities to earn industry-recognized credentials (IRCs) while in high school. IRCs are credentials conferred by businesses (e.g., Microsoft), industry groups (e.g., the National Center for Construction Education and Research or NCCER), or state certifying entities (e.g., the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation or TDLR) to individuals who demonstrate a sufficient level of knowledge and skills in a particular domain, often through one or more assessments. They are intended to prepare both students who plan to enter the workplace directly after high school for a career and college goers who want to build upon their IRC-related skills and capabilities in a postsecondary setting. In fact, the Texas Administrative Code says that industry certifications should be “portable,” in part meaning they can “be transferred seamlessly to postsecondary work through acceptance for credit or hours in core program courses at an institution of higher education.”14

Thus, while many IRCs require a bachelor’s degree (e.g., teaching licenses) or graduate degree (e.g., medical licenses), more than half of states now provide opportunities for students to earn other types of IRCs while in high school.15 In fact, forty-two out of forty-five states that responded to a national survey in 2019 reported that students in their state could earn some IRCs during high school.16Although eligibility for an IRC often occurs after students complete a respective, secondary CTE program of study, their conferral requires an independent assessment of skills and knowledge by the certifying business, industry, or state entity.

That external involvement by industry is meant to signal to prospective employers that an applicant has acquired at least some skills required for a specific position or occupation. Yet it’s unclear how well this works in practice. What little research has been done on such credentials provides grounds for concern,17 as do the seemingly questionable incentives tied to them in states’ accountability systems, as many of those systems prioritize quantity (number of IRCs obtained) over quality.18

To date, no study has examined the impact of specific IRCs earned at the high school level on the various employment or postsecondary outcomes they are meant to improve. To address this gap, this study uses data from Texas—a state that has taken an especially thoughtful approach to IRCs—to examine their impact on those outcomes and begin to assess which IRCs are making a real difference in students’ lives. Note that professional licenses, such as those for accountants, lawyers, and nurses, can also be considered IRCs, but our focus is on IRCs made available to students through state K–12 policy. IRCs that require education beyond a high school diploma, such as teaching or nursing licenses, are excluded from the set of IRCs examined in this study. Given historical concerns about inequity in CTE, the report also examines how student characteristics are associated with IRC receipt and whether IRCs truly provide an avenue to postsecondary success for historically underrepresented populations.

To date, no study has examined the impact of specific IRCs earned at the high school level on the various employment or postsecondary outcomes they are meant to improve. To address this gap, this study uses data from Texas—a state that has taken an especially thoughtful approach to IRCs—to examine their impact on those outcomes and begin to assess which IRCs are making a real difference in students’ lives. Note that professional licenses, such as those for accountants, lawyers, and nurses, can also be considered IRCs, but our focus is on IRCs made available to students through state K–12 policy. IRCs that require education beyond a high school diploma, such as teaching or nursing licenses, are excluded from the set of IRCs examined in this study. Given historical concerns about inequity in CTE, the report also examines how student characteristics are associated with IRC receipt and whether IRCs truly provide an avenue to postsecondary success for historically underrepresented populations.

Specifically, the study addresses the following questions:

1. What is the relationship between students’ acquisition of IRCs and their postsecondary educational and employment outcomes, and does this relationship vary across demographic groups?

2. What student, school, and geographic factors are most strongly related to students’ likelihood of earning an IRC?

3. How many students earn IRCs across Texas, and what kinds of IRCs do they earn?

4. How do students understand and perceive the value of IRCs?

State policy context

State policy context

This report draws on extensive longitudinal data representing more than one million students who graduated from public high schools in Texas between 2017 and 2019. Texas is an ideal setting for this study both due to the prominence of IRCs in state policy (more below) and its large and diverse population.19 It’s a state where most students in public schools are low income and/or students of color.

Like many states, Texas reimagined and expanded its CTE programs following the passage of the federal Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006 (Perkins IV). Critical to this transformation was passage of House Bill 22 in 2017, which directed the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to publish a list of approved IRCs that are recognized and valued by employers and to factor students’ receipt of such IRCs into the state’s public school accountability system.20 The TEA solicited extensive feedback from employers, workforce boards, postsecondary education institutions, and school districts to determine which credentials were most closely aligned with high-wage, in-demand occupations.21 It released a preliminary list in 2016–17 and a final one in 2017–18.22 This list is revised every two years, meaning that the IRCs approved in 2019–20 are in use until 2022–23.23 Students who complete any approved IRC are now considered college, career, and military ready (CCMR) in school accountability ratings.

Schools and districts were required to collect and report data on students’ acquisition of IRCs using the preliminary list in 2016–17. It showed that an estimated 2.7 percent of the roughly 350,000 high school graduates that year—nearly 10,000 students—earned an IRC before graduating, and that figure has risen considerably since.24

Data and Methodology

Data and Methodology

The bulk of this report uses Texas’s statewide longitudinal data system from the Texas Education Research Center, which includes individual-level data on nearly every public school student, public and private college enrollee, and employee in Texas. The study sample comprises more than one million students who graduated from a public high school in Texas during the 2016–17, 2017–18, and 2018–19 school years. Of that population, 5.9 percent (n = 60,727) earned at least one IRC before graduating, whereas 94.1 percent did not.25 Graduating cohorts in the sample are linked with information from Texas’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) wage system to determine whether they are employed, their industry of employment, and their earnings in the first year after graduating.26 State-level data from Massachusetts are also included in Appendix B to help contextualize the Texas results with those from another state.

To address questions about the rates of IRC acquisition and factors associated with them, the analysis uses descriptive statistics to identify the most common IRCs and certification subjects, examine the relationship between IRC receipt and CTE course taking, and explore how IRC receipt varies across student populations. Multilevel logistic regression models are used to estimate which student characteristics most strongly predict IRC receipt and calculate how much IRC receipt varies across schools, districts, and broad geographic regions.27

To examine the relationship between acquisition of IRCs and outcomes, the study uses regression models that control for the specific high schools that students graduated from and methods that match IRC recipients to a demographically and academically equivalent sample of IRC nonrecipients28 and compare results between matched groups. Data show whether students earned an IRC and what type they earned, as well as whether they concentrated in a CTE field and, if so, whether the certification is in that same field. Data on the share of students who complete a coherent CTE sequence of increasingly sophisticated courses is also used for some of the school- level analysis.

Postsecondary education outcomes include college enrollment (two- and four-year institutions) and persistence (continued enrollment in the second year). Labor outcomes include employment within the first twelve months after graduating high school, industry of employment, and first- year earnings.29 Finally, a “postsecondary-success” measure gauges whether a student enrolled in college or earned a decent income, which is set at 200 percent of the federal poverty line ($25,760), after high school.

To further contextualize the results, interviews and focus groups were conducted with a dozen high school students in Texas. The conversations probed students’ views of their CTE courses and programs, how they learned about IRCs and their experiences earning them, and their perceptions of the value of both CTE courses and the IRCs they earned or planned to earn. Accounts from the focus groups are embedded throughout the report, using pseudonyms to ensure anonymity, and appear under the heading “student voice.” For more information on the methods used in this report, see Appendix A.

Findings

How do IRCs shape students' short-term employment and educational outcomes?

- Section Summary

-

This section examines how IRCs relate to individual students’ experiences in the labor market immediately upon graduating from high school.30 The relationship between IRC receipt and students’ short-term employment and educational outcomes is mostly positive or neutral. IRC receipt is modestly but positively associated with overall college enrollment, four-year college enrollment, and college persistence, but this result is largely explained by the fact that the most common IRCs (Health Science and business) are positively linked to college outcomes, while several less common IRCs are inversely related. Regarding short-term workforce outcomes, a number of IRCs have a strong positive relationship with earnings, and the benefits of IRCs appear unaffected by one’s race, ethnicity, gender, or class background. Note, however, that while IRCs are positively associated with earnings, nearly all employed individuals are earning less than a living wage the year after graduating. When examining postsecondary success more comprehensively (i.e., including both workforce and educational outcomes), we see that IRCs in Information Technology, Health Science, and business have the best outcomes for students.

Taken together, the results imply that earning certain IRCs may be an effective strategy for improving students’ educational and earnings prospects, but many serve more as a stepping- stone to future career development rather than as a direct path to financial independence right out of high school.

Finding 1: In general, IRCs are weakly related to increases in short-term employment, while a few specific IRCs are positively related to increases in short-term earnings—particularly for students not attending college and part-time college students.

Table 1 shows how students’ short-term employment rates and median annual wages vary based on the IRC earned in high school. The first two columns include individuals who do not attend college, the next two include college students, and the final two include the full sample. For all samples, median earnings vary considerably across IRC fields, with the highest-earning group (Transportation) earning twice the amount of the lowest earning group (Arts and A/V).

Unsurprisingly, if paradoxically, IRC fields where students have lower college-enrollment rates show better employment outcomes—because few college students are working full time. For instance, Architecture and Construction ($9,576 median earnings), Education ($10,875), Cosmetology ($9,091), Manufacturing ($9,607), and Transportation ($11,667) have the highest median earnings, and tend to have the lowest college enrollment rates. For all those IRC fields, apart from Cosmetology, students earn at least 50 percent more compared to students who did not earn any IRC in high school. However, the employment rates are only modestly higher for those fields compared to students with no IRC (no more than eight percentage points). Conversely, IRC fields for which students had high college enrollment rates, such as Business, Health Science, and Information Technology, tend to have employment outcomes worse than or equivalent to students who did not earn any IRC.

Critically, median earnings were close to or below the poverty line for all individuals, irrespective of whether they earned an IRC in high school or the field in which they earned the IRC. Even for students who did not go to college after high school, 75 percent of them made less than approximately $15,300 in their first year after graduating, and even among students who did not enroll in college, fewer than 5 percent earned at least $30,000 their first year out of high school (not shown in the table below).

Table 1. IRC fields with lower college enrollment tend to have better employment outcomes.

|

|

HS grads, no college

(n = 501,090)

|

HS grads,

college enrollees

(n = 533,792)

|

All HS grads

(n = 1,034,882)

|

|

Employed (%)

|

Median Annual Earnings

|

Employed (%)

|

Median Annual Earnings

|

Employed (%)

|

Median Annual Earnings

|

|

Transportation

|

62.5

|

$13,767

|

78.3

|

$9,516

|

68.1

|

$11,667

|

|

Manufacturing

|

66.7

|

$13,422

|

71.9

|

$6,284

|

68.9

|

$9,607

|

|

Education

|

65.4

|

$12,622

|

74.2

|

$9,139

|

70.2

|

$10,875

|

|

Architecture and Construction

|

65.7

|

$12,268

|

72.6

|

$7,028

|

68.4

|

$9,576

|

|

Cosmetology

|

62.1

|

$10,896

|

73.3

|

$7,707

|

66.9

|

$9,091

|

|

Health Science

|

56.7

|

$8,659

|

73.9

|

$5,586

|

69.4

|

$6,084

|

|

Hospitality and Tourism

|

62.7

|

$8,375

|

74.5

|

$6,381

|

68.6

|

$7,160

|

|

Public Safety

|

59.9

|

$8,164

|

69.9

|

$5,570

|

66

|

$6,480

|

|

Business

|

50.9

|

$7,950

|

67.7

|

$4,706

|

61.8

|

$5,533

|

|

Agriculture

|

58.6

|

$7,931

|

73.9

|

$4,708

|

68.2

|

$5,444

|

|

Information Technology

|

46.4

|

$6,777

|

66.7

|

$5,543

|

59.2

|

$5,823

|

|

Arts and A/V

|

49.9

|

$6,722

|

62.6

|

$4,379

|

57.4

|

$5,008

|

|

No IRC

|

59.1

|

$8,129

|

73

|

$4,916

|

66.2

|

$6,097

|

|

Any IRC

|

64.8

|

$10,016

|

68.2

|

$6,062

|

66.6

|

$7,421

|

|

Multiple IRCs

|

63.6

|

$12,676

|

67.7

|

$5,843

|

65.8

|

$8,699

|

|

All Students

|

59.1

|

$8,244

|

72.9

|

$4,964

|

66.2

|

$6,157

|

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 for calculations of employment and within the first year of graduating high school for calculations of earnings. Earnings are for part-time and full-time workers.

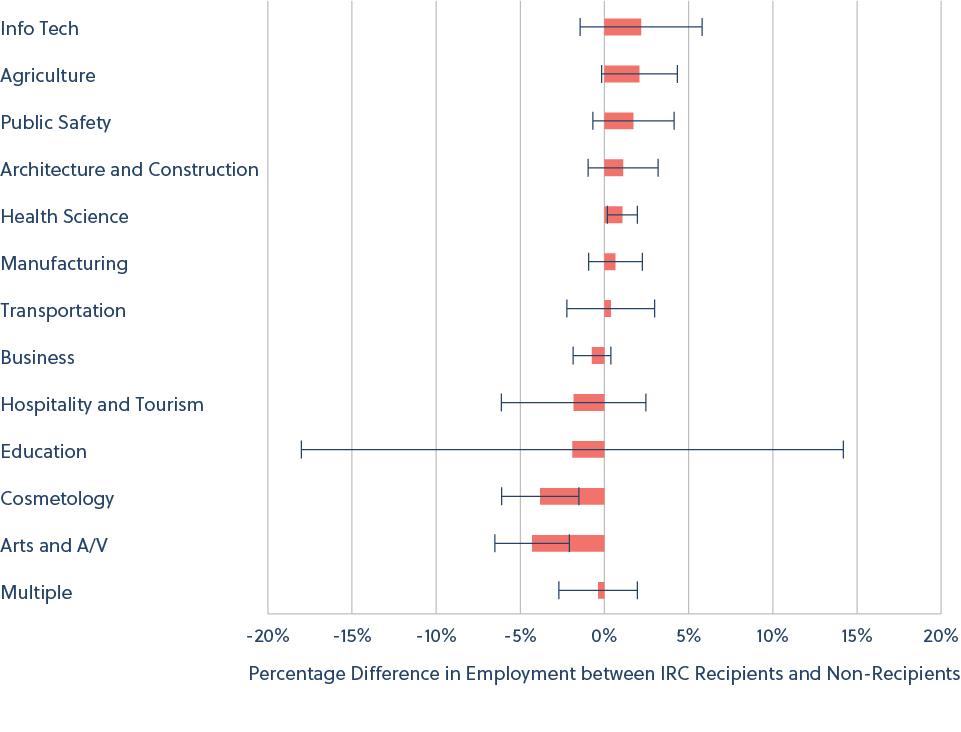

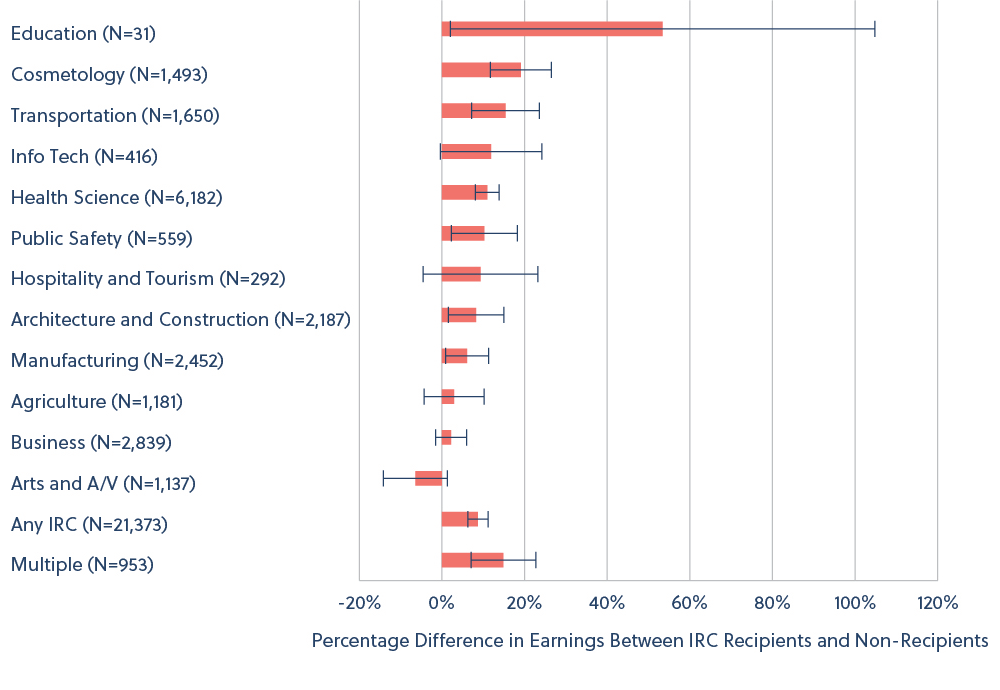

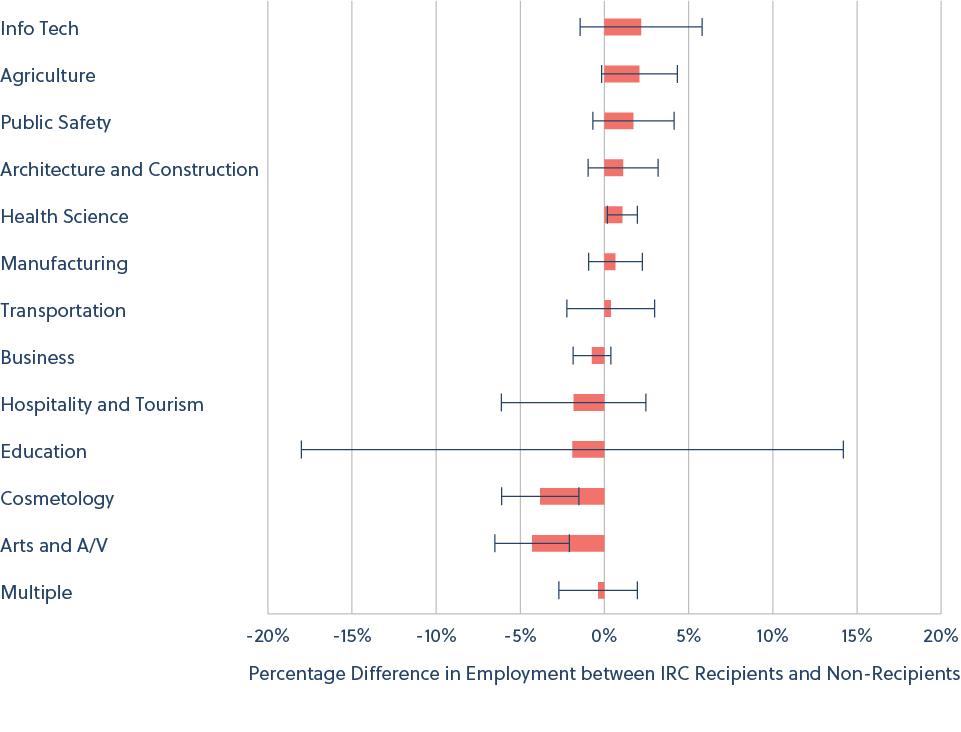

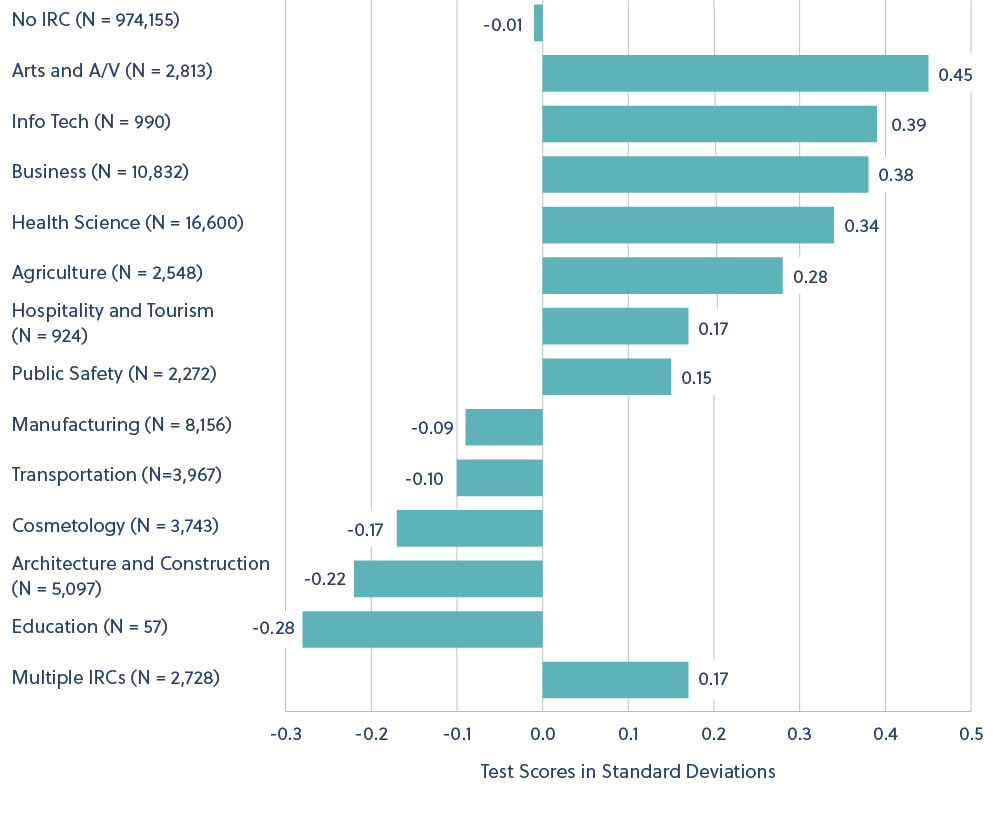

Although the results in Table 1 suggest variation in employment and earnings across IRC categories and IRC nonrecipients, many of these differences disappear once controls are added. Specifically, after CTE coursework and student characteristics have been accounted for,31 few IRC fields show either a positive or negative relationship to students’ employment prospects.32 Per Figure 1, only Health Science IRCs statistically improve employment likelihood, and even then only modestly, while students who earned both Arts and A/V and Cosmetology IRCs have lower likelihood of employment.

Figure 1. Few IRCs show either a positive or negative relationship with employment once college enrollment and other student characteristics are accounted for.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are large for education because only fifty-seven students are represented across all three years of data.

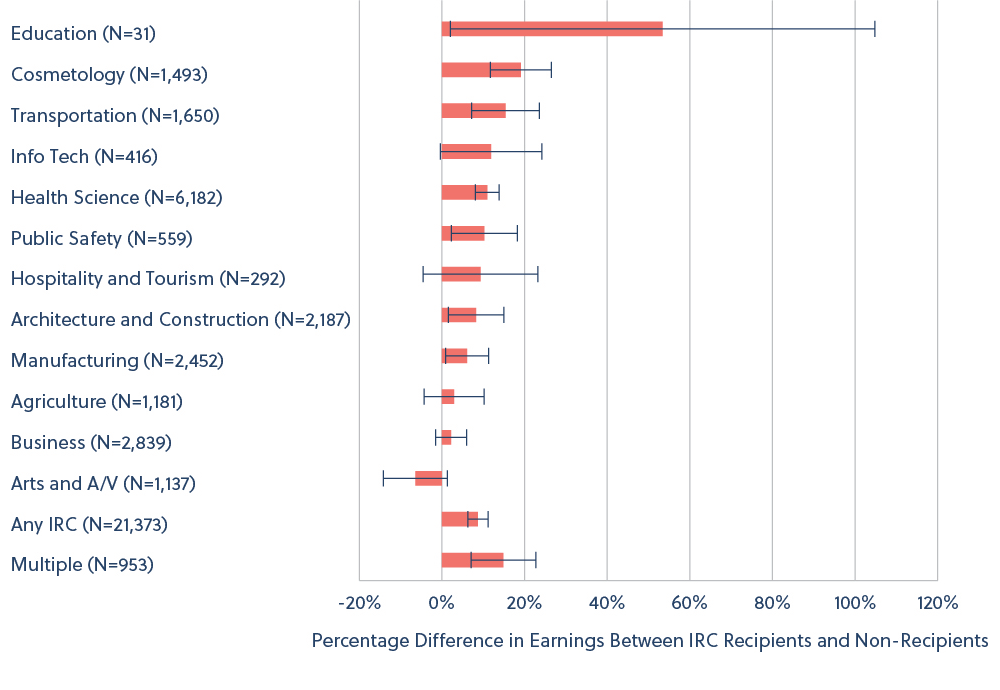

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are large for education because only fifty-seven students are represented across all three years of data.Although we find little relationship between IRC receipt and students’ immediate employment, findings suggest that certifications are much more strongly and positively related to first-year earnings for students who are employed (Figure 2).33 On average, receipt of an IRC is related to a roughly 9 percent increase in annual earnings for the full sample of high school graduates, controlling for college enrollment (Figure 2, “Any IRC”). This estimate is relatively consistent across student samples, with the largest estimated increase in earnings found for students not attending college at 12.6 percent, followed by full-time college students at 9.6 percent and finally part-time college students at 8.8 percent (see Appendix A, Table A6). Given that the estimated median earnings for students who did not earn an IRC and did not attend college was $8,129 (see Table 1), a 12.6 percent increase in earnings translates into an additional $1,024 annually.

Figure 2. A number of IRCs are positively related to earnings, with cosmetology providing the largest reliable earnings benefit.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering 350,876 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 who were both employed and enrolled in college in their first year after graduating high school. The statistical model controls for the number of credit hours students attempted in their first year. The outcome variable is the natural logarithm of first-year earnings. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are large for education because only thirty-one students are represented across all three years of data.

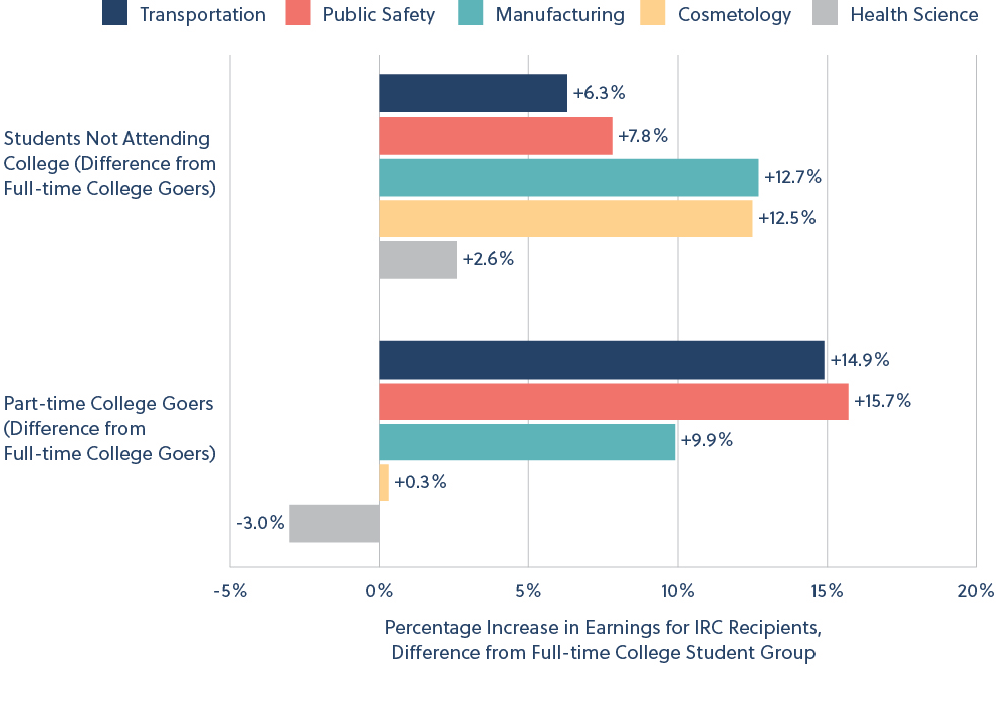

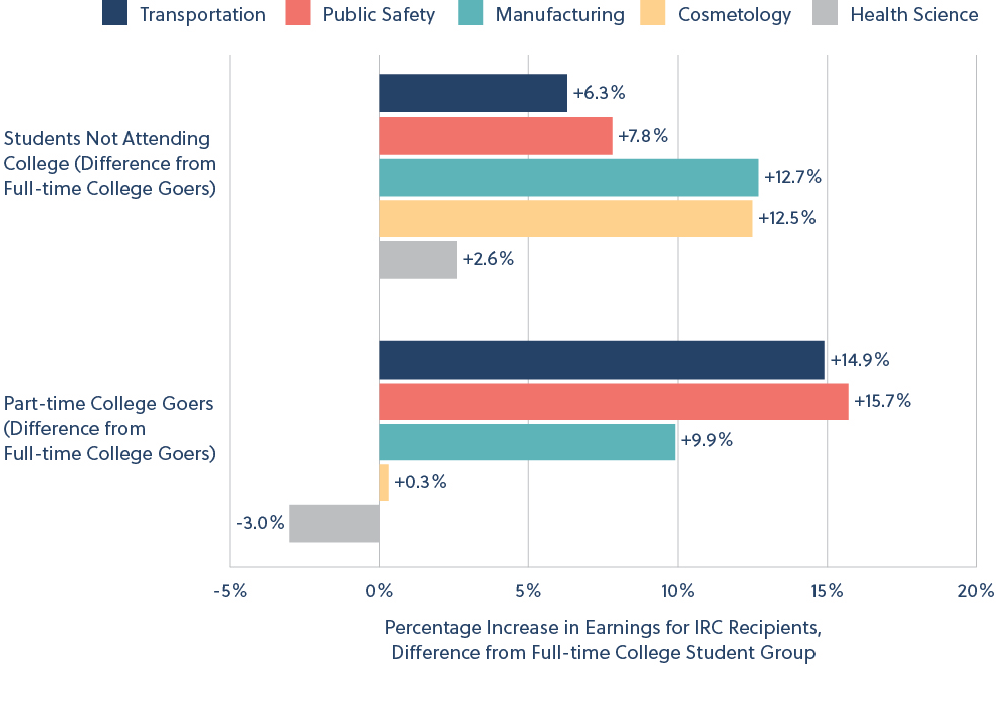

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering 350,876 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 who were both employed and enrolled in college in their first year after graduating high school. The statistical model controls for the number of credit hours students attempted in their first year. The outcome variable is the natural logarithm of first-year earnings. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are large for education because only thirty-one students are represented across all three years of data.The estimated earnings increase—again measured within the first year of graduating high school—tends to be largest for either students not attending college or part-time students. For the former, the largest boosts in earnings come from IRCs in Manufacturing, Cosmetology, and Health Science, while for part-time college students the largest increases come from Cosmetology, Transportation, and Public Safety. Cosmetology boasts the largest estimates overall, associated with an impressive 31.1 percent increase in earnings for individuals who do not enroll in college after high school, 12.5 percentage points greater than the boost full-time college students receive (Figure 3). Likewise, the Manufacturing IRC is associated with a 15.2 percent increase in earnings for individuals who do not go to college, 12.7 percentage points greater than the small boost full-time college students receive. Again, given the threat of selection bias, these estimates cannot be interpreted as causal, but they do suggest that IRCs have clear value for students entering the labor market after high school.

Figure 3. IRC earnings gains are generally greater for recipients who do not attend college or attend part-time than for full-time college students.

Note. This figure contains data for selected IRCs. Full results of these models appear in Appendix A, Table A6.

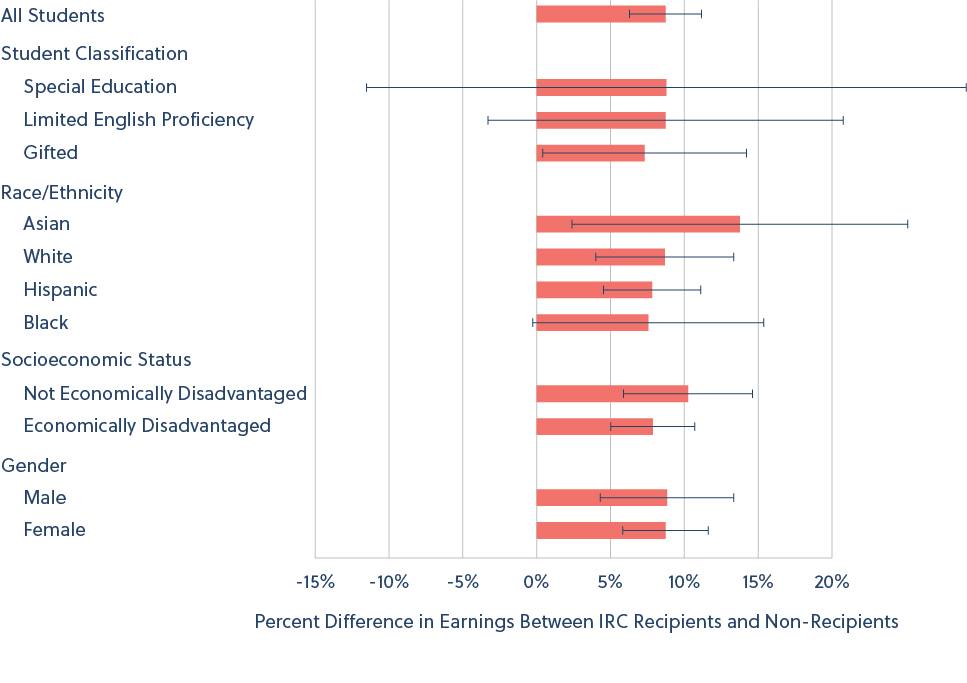

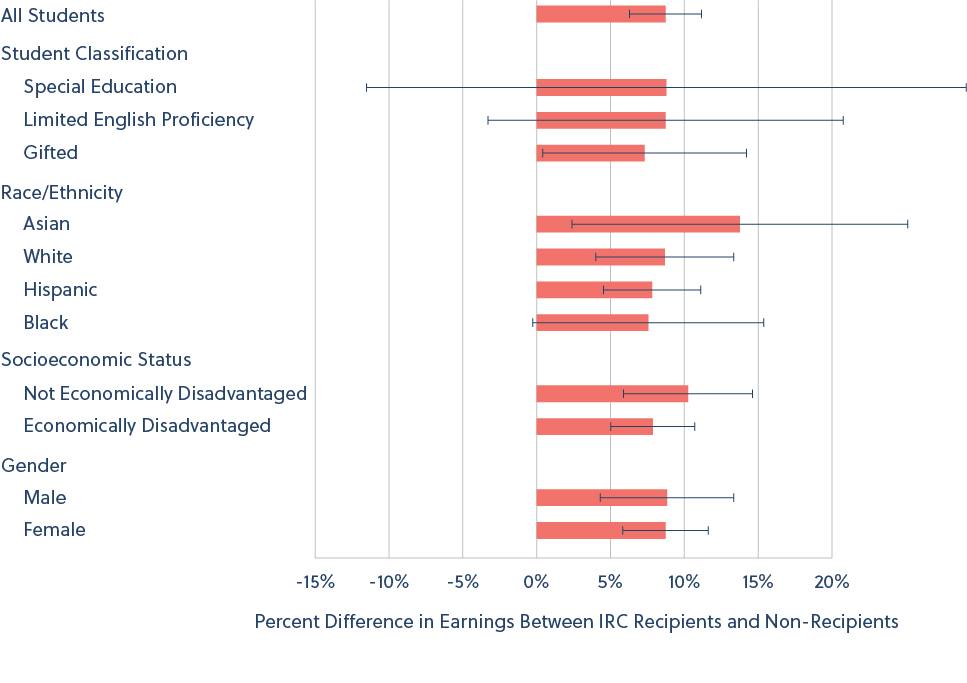

Note. This figure contains data for selected IRCs. Full results of these models appear in Appendix A, Table A6.Figure 4 shows by demographic group, the relationship between IRC receipt and earnings among those who received an IRC in a CTE field of concentration in high school. There is remarkable consistency in the relationship between IRC receipt and earnings, which is within 1 to 2 percentage points of the 9 percent increase for nearly every demographic group, apart from Asian students. Put differently, we find minimal differences in the relationship between IRC receipt and earnings by gender, race/ethnicity, economic status, LEP, special-education status, or gifted status.

Figure 4. The relationship between IRC receipt in a field of CTE concentration and first-year earnings is remarkably consistent across demographic groups.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 685,469 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 who were employed within the first year of graduating high school. The natural logarithm of earnings was used as the outcome variable. The estimated differences are between students who earned an IRC in the same CTE subject in which they concentrated and all other students (whether they earned an IRC, participated in CTE, or did neither). Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 685,469 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 who were employed within the first year of graduating high school. The natural logarithm of earnings was used as the outcome variable. The estimated differences are between students who earned an IRC in the same CTE subject in which they concentrated and all other students (whether they earned an IRC, participated in CTE, or did neither). Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.Finding 2: IRCs in Agriculture, Business, and Health Science are positively associated with college enrollment and persistence, but those in Cosmetology, Manufacturing, and Transportation are negatively associated.

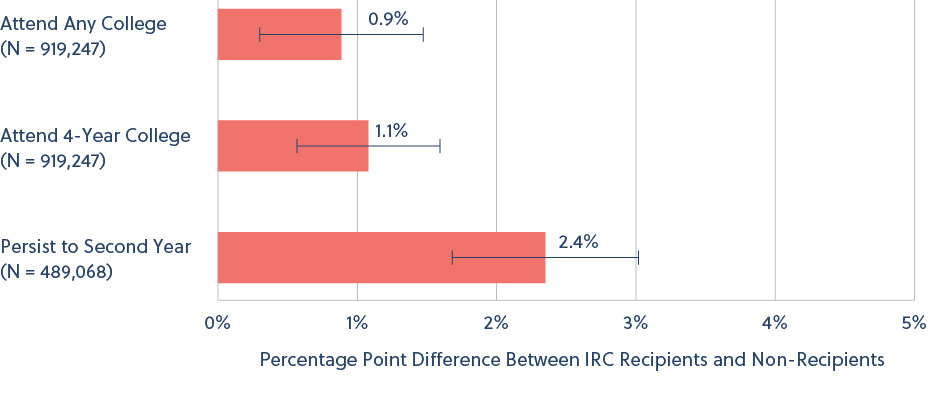

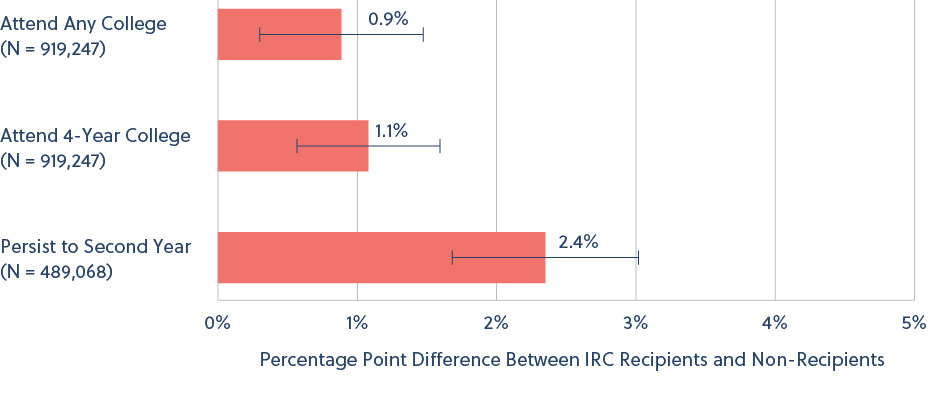

Overall, receipt of any IRC is modestly but positively related to students’ early college outcomes. Estimates of the relationship between IRC receipt and college enrollment did not exceed roughly one percentage point (Figure 5).34 Yet, IRC receipt is more positively correlated with college persistence (continuing for a second year of college): students who earn any IRC are about three percentage points more likely to persist. In general, our findings suggest that the relationship between IRC receipt and early college outcomes is positive but modest, and we find no evidence that IRC receipt deters students from college attendance on average.

Figure 5. Receipt of any IRC is modestly but positively related to college outcomes.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.This positive but modest relationship is likely driven by the fact that Business and Health Science (and, to a lesser degree, Agriculture and Information Technology) comprise the majority of IRCs and are both positively associated with college-going and persistence compared to their peers (Figure 6).35 On the other hand, students who earn IRCs in Architecture and Construction, Hospitality and Tourism, Cosmetology, Manufacturing, and Transportation have lower odds of college enrollment in general and four-year college enrollment in particular. Students who earn Hospitality and Tourism and Transportation IRCs are also less likely to persist in college.

Figure 6. Some IRCs, such as Health Science and Information Technology, are associated with better postsecondary education outcomes, while others, such as Cosmetology and Transportation, are associated with worse postsecondary education outcomes.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. N sizes for each IRC area in parentheses are for the two attendance outcomes. Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. N sizes for each IRC area in parentheses are for the two attendance outcomes. Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.Finding 3: Only a handful of IRCs are related to overall success beyond high school.

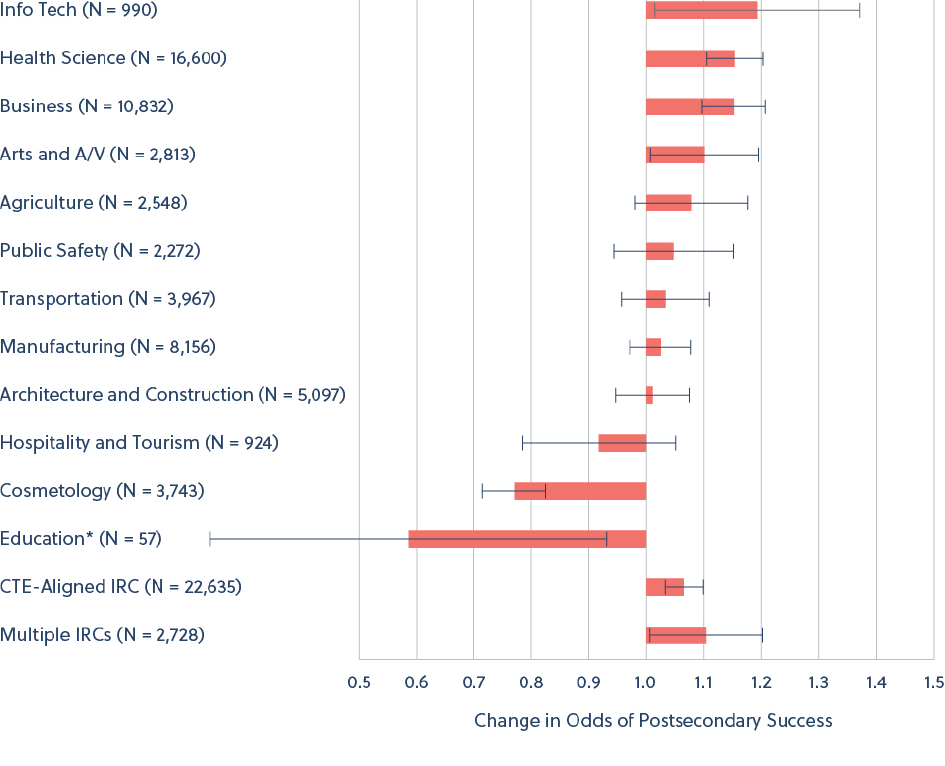

Up to this point, results show that IRCs that are positively linked to college enrollment often provide less immediate labor market benefit, while those positively linked to earnings are inversely related to college going. Put differently, there appears to be a trade-off between certifications that facilitate the transition into postsecondary education and those that provide immediate labor-market value, which leads to the question: which IRCs best promote postsecondary success overall?

provide immediate labor-market value, which leads to the question: which IRCs best promote postsecondary success overall?

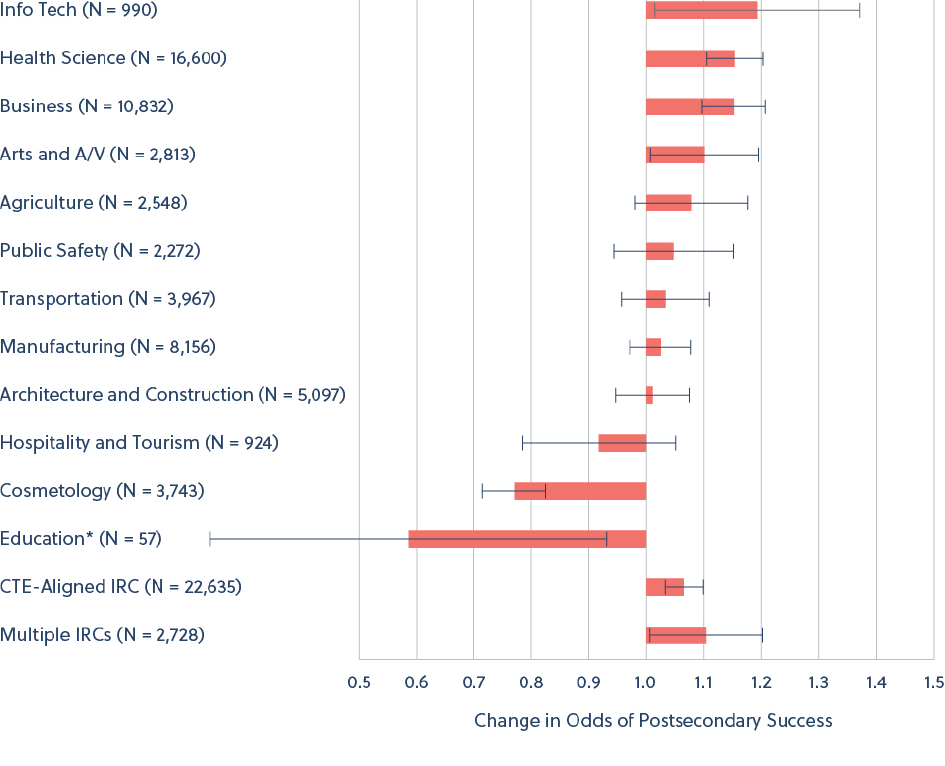

In this report, such success is defined as college enrollment or earning 200 percent of the poverty line for a single adult ($25,760).36 Figure 7 shows, that after controlling for subject-specific CTE coursework and other student factors, just four IRCs (Information Technology, Health Science, Business, and Arts and A/V) meet that definition for student success, while the Cosmetology IRC generally reduces students’ chances of hitting this mark (the Education IRC has too few students for a reliable estimate).

Recall that previous analyses suggested that Cosmetology IRCs were most strongly associated with increases in first-year earnings. Nevertheless, the combination of extremely low rates of college enrollment among Cosmetology IRC recipients and the fact that few students in the sample earn more than the income threshold results in a negative link between Cosmetology IRCs and postsecondary success.

Finally, when looking just at the effects of CTE-aligned IRCs—meaning students have concentrated in a CTE cluster and have earned an IRC in the same subject area—we find that completing this coursework and receiving an IRC is estimated to significantly improve students’ odds of postsecondary success overall (see Table A7 in Appendix A for full data).

Figure 7. A number of IRCs are modestly but significantly related to overall postsecondary success.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. The outcomes are odds ratios of postsecondary success, which is defined as college enrollment or earning 200 percent of the poverty line for a single adult ($25,760), between IRC recipients and nonrecipients. CTE-aligned IRCs are those for which students have concentrated in a CTE cluster and have earned an IRC in the same subject area. Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. The outcomes are odds ratios of postsecondary success, which is defined as college enrollment or earning 200 percent of the poverty line for a single adult ($25,760), between IRC recipients and nonrecipients. CTE-aligned IRCs are those for which students have concentrated in a CTE cluster and have earned an IRC in the same subject area. Bars show 95 percent confidence intervals.How do IRCs shape student trajectories?

- Section Summary

-

The connection between IRC receipt and students’ choice of college major and industry of employment are not tightly aligned, suggesting that the vast majority of students will go on to work or study outside of their IRC field. This suggests that IRCs may have educational value even if students pursue fields other than the one related to it, but opportunities clearly exist to better align CTE pathways at the K–12 level with postsecondary education programs to pave transitions into college.

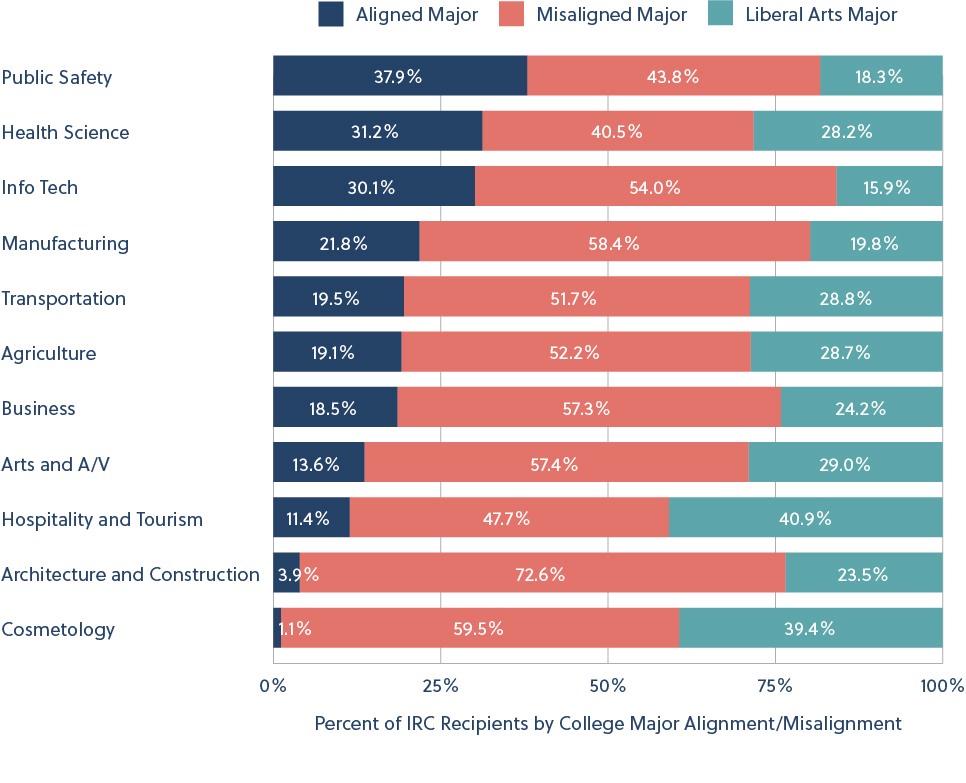

Finding 4: The majority of students who earn IRCs are not employed in the industry most closely aligned with their credentials (if they enter the workforce), nor are they enrolled in related college majors (if they go to college).

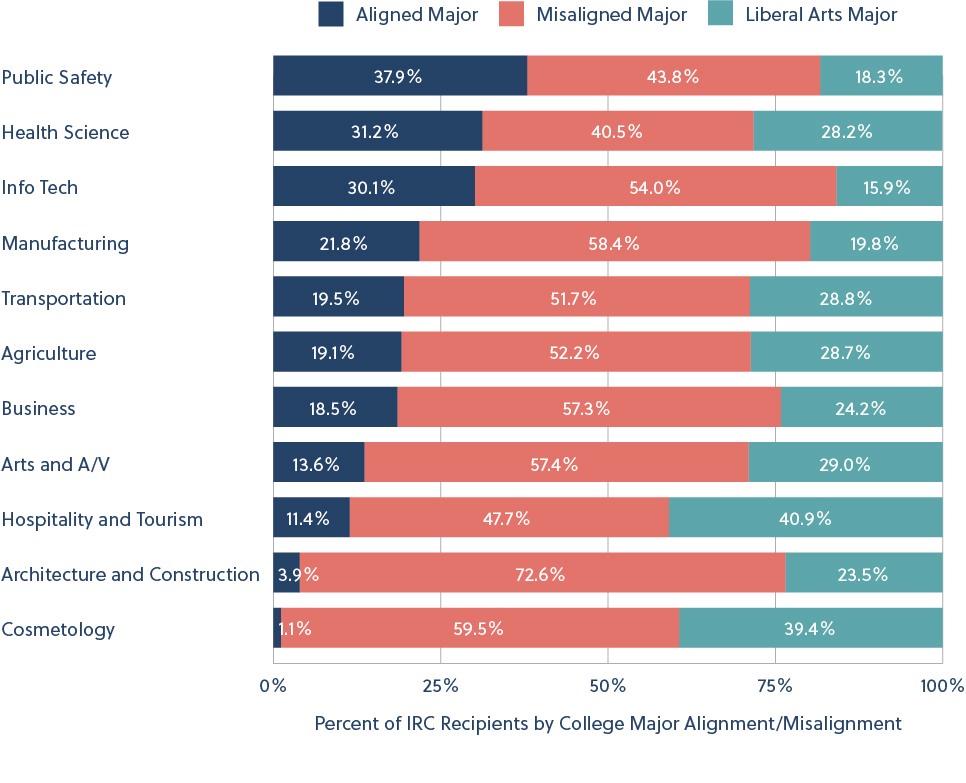

Figure 8 shows whether students who earned an IRC in a specific subject later selected a college major that was aligned to it.37 The sample is restricted to students who enrolled in college their first year after high school. Two points are noteworthy. First, students are more likely to pursue majors outside of their IRC subject, except for a few fields that drive the overall positive correlation between alignment of IRC receipt and college major. For example, 38 percent of Public Safety IRC recipients majored in the field in college, whereas just 12 percent of other students majored in Public Safety (latter not shown). Likewise, 31 percent of students who earned Health Science IRCs in high school majored in Health Science, compared to 8 percent of non-IRC recipients who pursued those same majors; the comparable figures for Information Technology IRC and non-IRC recipients is 30 and 3 percent, respectively.

Clearly, some IRCs are more tightly aligned with what students major in college. Whereas more than one-third of Public Safety38 IRC recipients are pursuing majors related to the subject of their certification, that rate is less than 20 percent for the majority of IRC categories and less than 5 percent for two categories (Architecture and Construction and Cosmetology). Across the full sample, less than one-quarter (23 percent) of all IRC recipients who enrolled in college after high school are majoring in the same subject in which they earned their certification (not shown).

Second, for all IRC subjects except for Health Science and Information Technology, the most popular major is Liberal Arts and Sciences. This major includes a curriculum that meets most (if not all) lower-division requirements for any two- or four-year program of study across public institutions in Texas and is most commonly pursued by two-year students seeking to transfer to a four-year university. It is difficult to say definitively whether this is a good or a bad thing; hence Figure 8 presents this major separately from the “aligned” and “misaligned” categories of majors. On one hand, it shows that students earning IRCs in high school are not solely diverted into technical programs and are still quite likely to pursue traditional academic pathways once they get to higher education. On the other hand, there is clearly plenty of room for improvement in helping students align the IRCs they earn in high school with their future postsecondary pathways.

Figure 8. Students are more likely to pursue majors outside of their IRC area, although Public Safety, Health Science, and Information Technology students are relatively likely to major in their field after beginning college.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 34,875 high school graduates who completed IRCs in the state from 2017 through 2019 and enrolled in college within the first year after graduating high school. Majors were coded using the National Center for Education Statistics’ Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes, specifically the two-digit CIP codes that indicate the broad major area. Cosmetology majors were considered to have enrolled in an aligned major if their major CIP code was equal to “Personal and Culinary Services,” which includes majors for cosmetology programs.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 34,875 high school graduates who completed IRCs in the state from 2017 through 2019 and enrolled in college within the first year after graduating high school. Majors were coded using the National Center for Education Statistics’ Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes, specifically the two-digit CIP codes that indicate the broad major area. Cosmetology majors were considered to have enrolled in an aligned major if their major CIP code was equal to “Personal and Culinary Services,” which includes majors for cosmetology programs.Recall that previous findings suggest that IRCs are not strongly related to students’ likelihood of being employed but are positively linked to earnings among students who work after high school, regardless of their demographic background or college-enrollment status. Next, we investigate the relationship between IRC receipt and the industry in which students are employed. Ideally, the analysis would determine whether students are working in a job or occupation aligned with their certification, but Texas wage data do not allow such fine-grained investigation. So we categorize industries based on NAICS codes, which group all employers into one of twenty broad industry areas (see Appendix A, Table A8, for a crosswalk of how IRC fields and NAICS codes align).

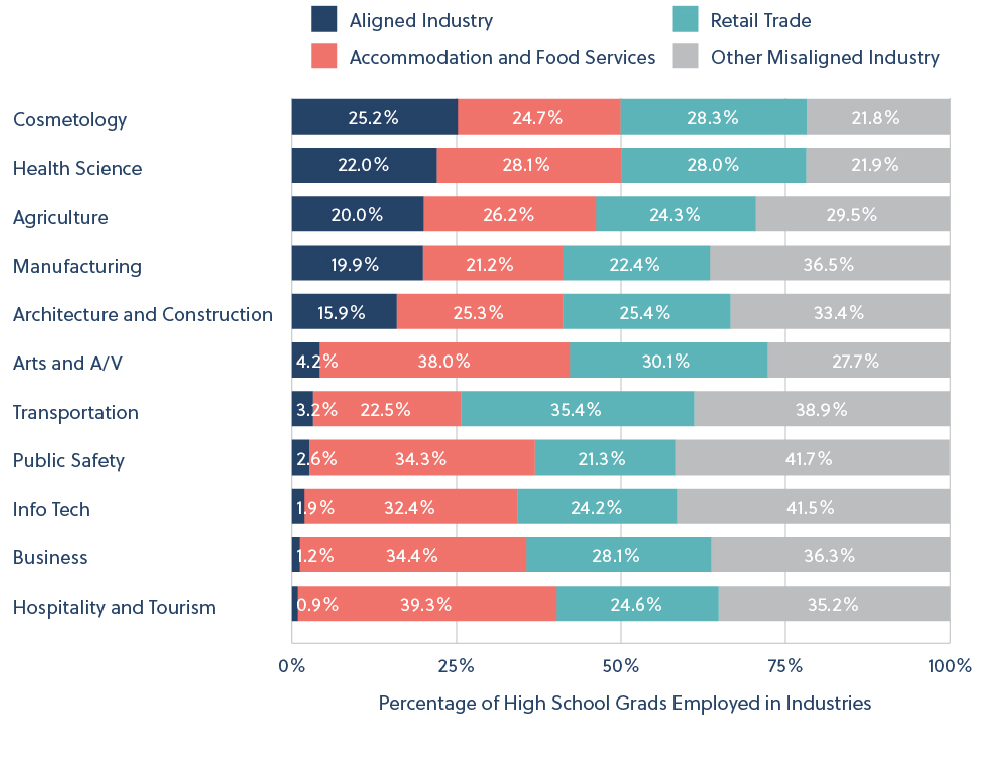

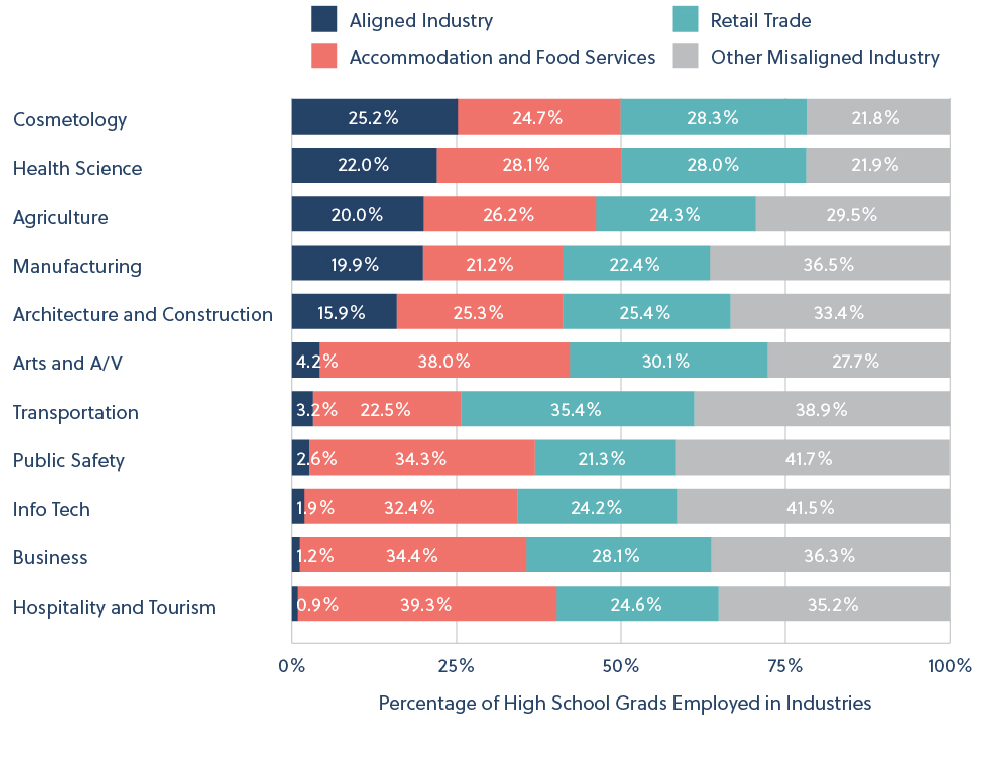

Results show that in all IRC areas, no more than one-quarter of employed students are working in an aligned industry (Figure 9). Compared to students who did not earn an IRC, those who received one in Cosmetology, Health Science, Agriculture, Manufacturing, or Architecture and Construction are considerably more likely to be employed in the respective industries. For the remaining IRC fields, fewer than 5 percent of employees are working in an aligned industry, including in Arts and A/V, Transportation, Public Safety, Information Technology, Business, and Hospitality and Tourism. The majority of recent high school graduates are employed in either the Accommodation and Food Services or Retail Trade industries, which provide many entry-level jobs for early career workers.

Figure 9. There is a modest relationship between IRC field and industry of employment, although employment in Accommodation and Food Services and Retail is most common for all IRC earners.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 685,469 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 who were employed within the first year of graduating high school. To see a list of aligned industries to each of the eleven IRC areas, see Table A8 in Appendix A. “Retail Trade and Accommodation and Food Services” industries are kept separate given how common it is for recent high school graduates to be employed in these sectors, but note that the latter category could overlap with “Hospitality and Tourism.” Of employed students who do not earn any IRCs, 34.1 percent work in Accommodation and Food Services and 27.6 percent work in Retail Trade.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 685,469 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 who were employed within the first year of graduating high school. To see a list of aligned industries to each of the eleven IRC areas, see Table A8 in Appendix A. “Retail Trade and Accommodation and Food Services” industries are kept separate given how common it is for recent high school graduates to be employed in these sectors, but note that the latter category could overlap with “Hospitality and Tourism.” Of employed students who do not earn any IRCs, 34.1 percent work in Accommodation and Food Services and 27.6 percent work in Retail Trade.

How popular are IRCs?

- Section Summary

-

Overall, IRCs are becoming increasingly widespread, and certain student populations are more likely to earn IRCs compared to their peers: CTE concentrators as well as Hispanic and Asian, economically disadvantaged, and high-achieving students. But variance across schools far outweighs the combined predictive effect of all the analyzed student characteristics.

Finding 5: CTE concentrators, as well as Hispanic, Asian, and higher-achieving students are most likely to earn IRCs, while schools (not students’ race/ethnicity or socioeconomic background) are the most important predictor of earning an IRC.39

Finding 5: CTE concentrators, as well as Hispanic, Asian, and higher-achieving students are most likely to earn IRCs, while schools (not students’ race/ethnicity or socioeconomic background) are the most important predictor of earning an IRC.39

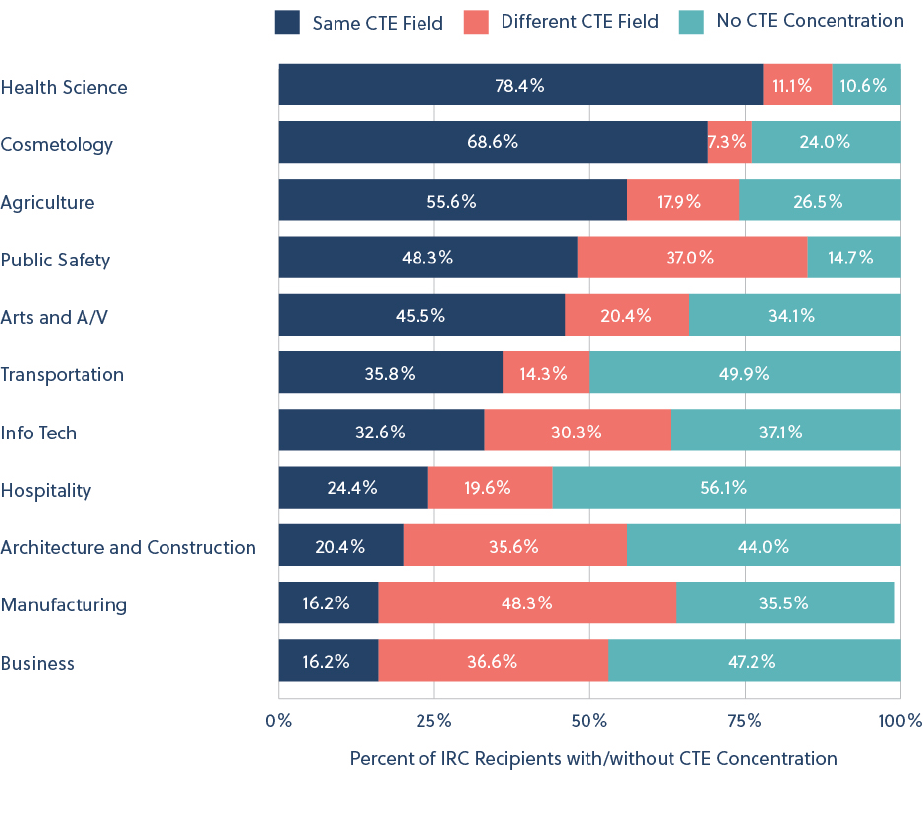

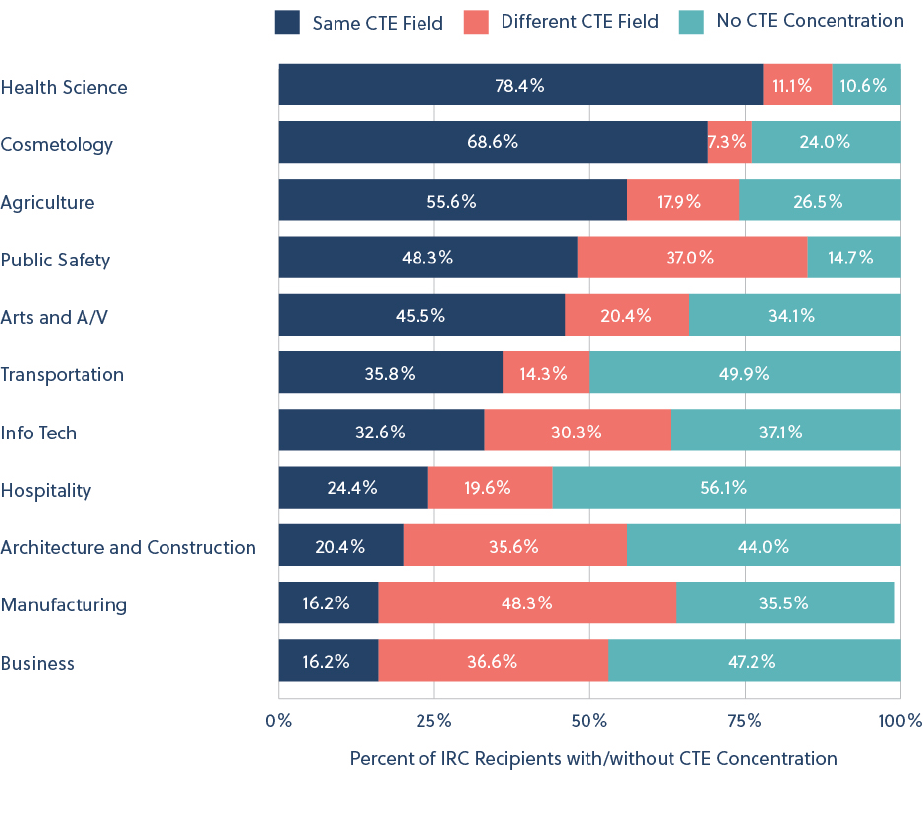

Findings show that there is a strong relationship between CTE course taking and IRC receipt. Figure 10 highlights the relationship between the IRCs that students earned and the CTE subject in which they did or did not concentrate (defined as earning three or more credits in the same CTE subject). Each bar represents the group of students who earned an IRC in that subject, with dark blue showing the percentage of students who concentrated in the same CTE area as the subject of their certification, coral showing the percentage who concentrated in a different CTE area, and teal showing the percentage with no CTE concentration. In the Health Science, Cosmetology, and Agriculture fields, more than half of students concentrated in the same CTE area as their IRC, including more than three quarters of students in Health Science. In contrast, in the fields of Information Technology, Hospitality, Architecture and Construction, Manufacturing, and Business, nearly a third to almost half of students who earned the respective certification concentrated in a different CTE field (with the remainder not concentrating at all).40 This may seem odd, but fields vary in how closely aligned their IRCs are with CTE coursework. For example, they are tightly coupled in fields like Cosmetology and Health Science but much more loosely related in fields such as Business, Manufacturing, and Transportation.41

Figure 10. There is a strong relationship between IRCs and CTE fields for many certifications but not all of them.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering the 60,727 high school graduates in the state who earned at least one IRC in the respective certification field from 2017 through 2019.

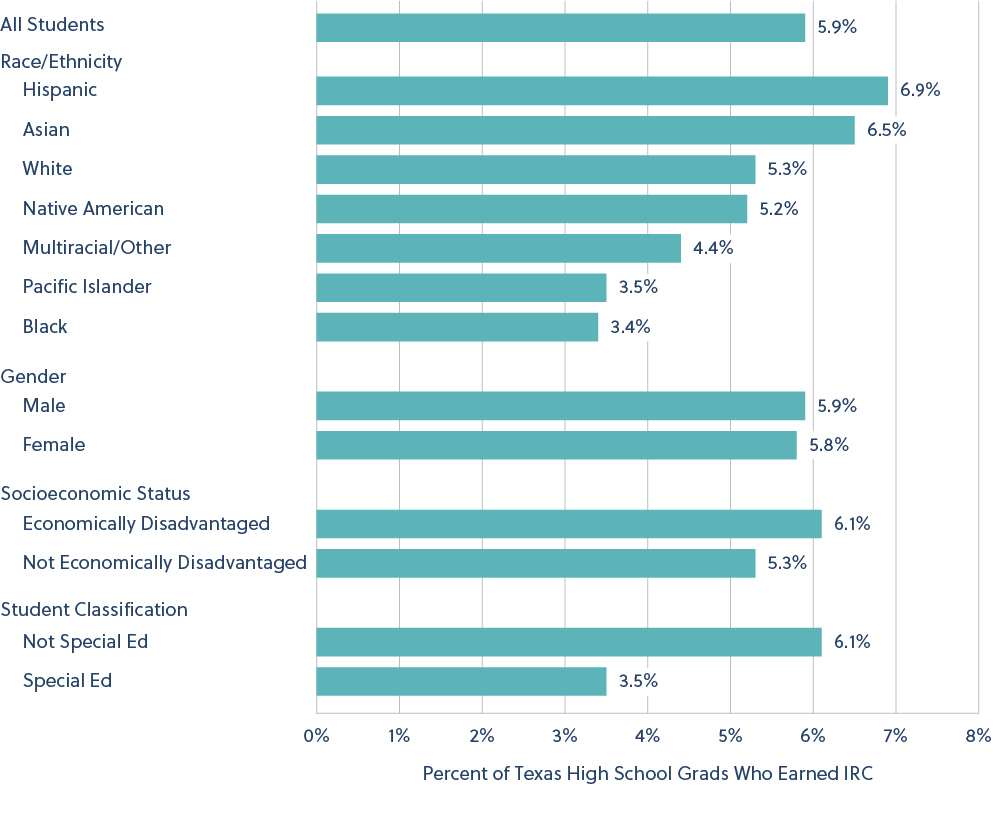

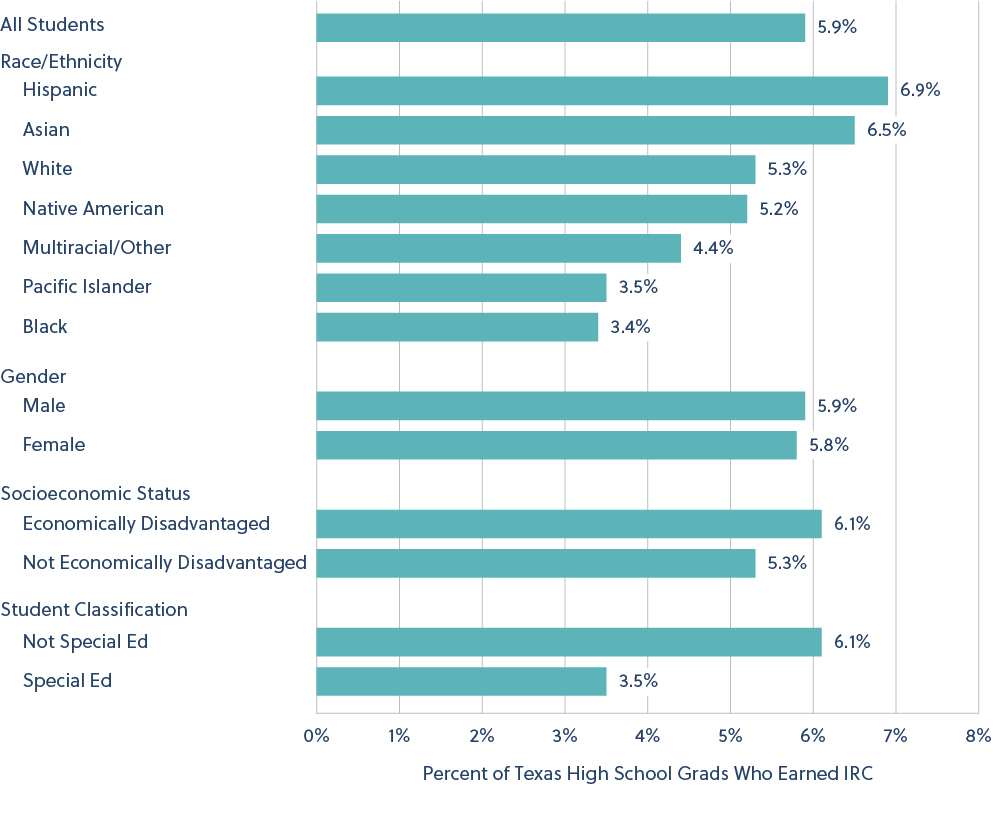

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering the 60,727 high school graduates in the state who earned at least one IRC in the respective certification field from 2017 through 2019.Figure 11 shows how IRC rates vary across racial/ethnic, gender, economic, and special-education populations. The results by race/ethnicity highlight the diversity in certification rates across student groups: Black students have the lowest rate of earning certifications (3.4 percent), while Hispanic students have the highest rate (6.9 percent). Native American (5.2 percent) and White (5.3 percent) students have nearly equivalent rates that are closer to the statewide average for the three cohorts (5.9 percent). There is almost no difference between male and female students in their likelihood of earning an IRC (5.8 percent vs. 5.9 percent), and economically disadvantaged students are only marginally more likely to earn a certification compared to nondisadvantaged students (6.1 percent vs. 5.3 percent). However, special-education students are considerably less likely to receive an IRC compared to students who were not receiving special-education services (3.5 percent vs. 6.1 percent).42

Figure 11. Race/ethnicity and special-education status more strongly relate to IRC rates than gender or economic status.

Figure 11. Race/ethnicity and special-education status more strongly relate to IRC rates than gender or economic status.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019.Variation in IRC receipt rates across demographic groups is somewhat greater when considering the certification area (Table 2). For example, at .17 percent, Asian students are the least likely to earn IRCs in Architecture and Construction but most likely to receive them in Health Science (nearly 4 percent).43 In contrast, Hispanic students are the most likely to earn IRCs in Architecture and Construction, Public Safety, and Transportation. Native American students are close to the average for most areas but have the highest rates of earning Information Technology IRCs (.24 percent). Pacific Islander students have below-average rates of certifications for all areas, apart from Arts and A/V. White students are most likely to earn Agriculture certifications (.35 percent) but are close to the statewide average for most other areas. Black students have below-average certification rates in all subjects.

Table 2. Health Science and Business IRCs are the most popular for all student groups, but there is some variation among ethnic/racial student subgroups.

|

IRCs

|

Percentage of Students Earning IRC |

| |

Statewide Average

(All Students) |

Hispanic |

Asian |

White |

Native American |

Multiracial/Other |

Pacific Islander |

Black |

| Health Sciences |

1.90 |

2.07 |

3.58 |

1.65 |

1.68 |

1.87 |

1.58 |

1.26 |

| Business |

1.50 |

1.65 |

2.32 |

1.40 |

1.23 |

1.13 |

0.76 |

0.96 |

| Manufacturing |

1.02 |

1.23 |

0.42 |

1.13 |

0.97 |

0.54 |

0.38 |

0.26 |

| Transportation |

0.85 |

1.04 |

0.33 |

0.86 |

0.68 |

0.64 |

0.51 |

0.30 |

| Architecture and Construction |

0.66 |

0.86 |

0.17 |

0.54 |

0.60 |

0.41 |

0.57 |

0.42 |

| Arts & A/V |

0.39 |

0.42 |

0.63 |

0.37 |

0.37 |

0.46 |

0.51 |

0.24 |

| Cosmetology |

0.37 |

0.54 |

0.10 |

0.21 |

0.31 |

0.16 |

0.06 |

0.23 |

| Public Safety |

0.28 |

0.44 |

0.18 |

0.13 |

0.03 |

0.14 |

0.13 |

0.07 |

| Agriculture |

0.27 |

0.25 |

0.3 |

0.35 |

0.29 |

0.28 |

0.13 |

0.17 |

| IT |

0.12 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

0.10 |

0.24 |

0.09 |

<0.01 |

0.03 |

| Hospitality and Tourism |

0.10 |

0.11 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.13 |

0.10 |

<0.01 |

0.09 |

| Any IRC |

5.90 |

6.90 |

6.50 |

5.30 |

5.20 |

4.40 |

3.50 |

3.40 |

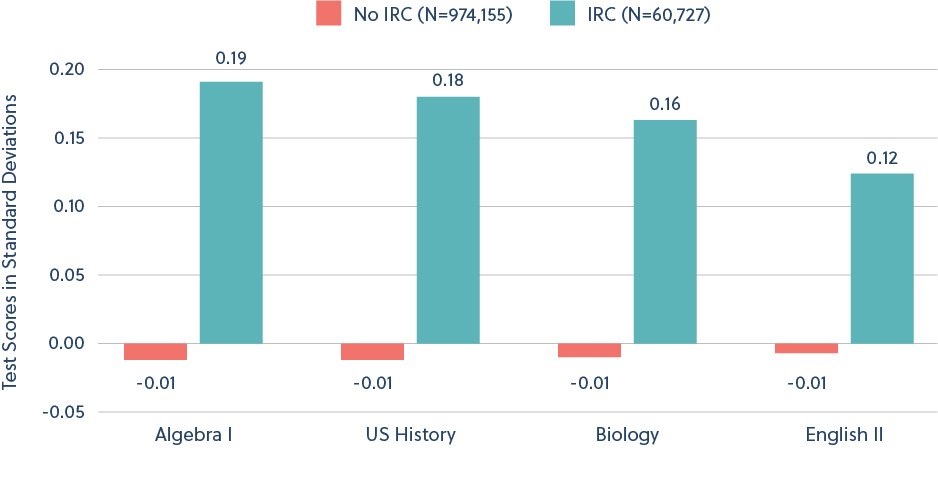

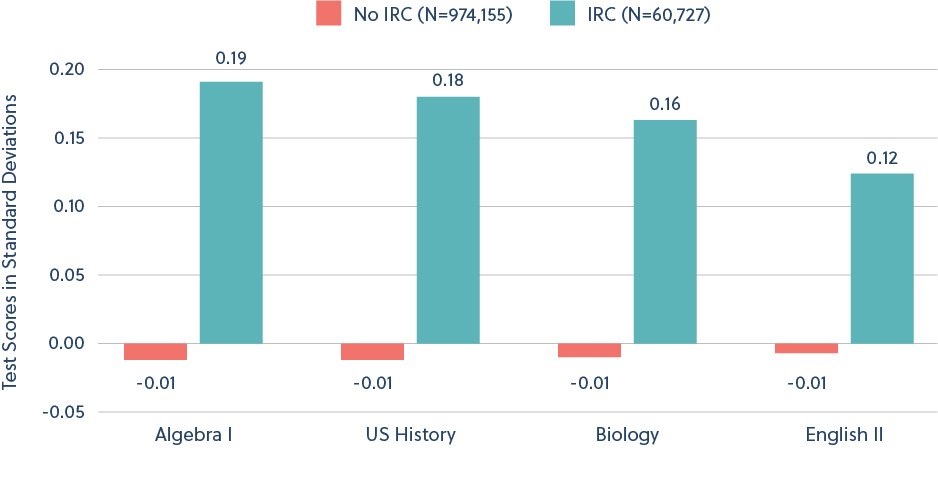

Somewhat surprisingly, we find that IRC recipients are considerably higher achieving than nonrecipients on average. Figure 12 presents students’ mean performance on state standardized tests in four subject areas (Algebra I, U.S. History, Biology, and English II) by whether students earned any certification. The difference between IRC recipients and nonrecipients ranges from roughly one-eighth of a standard deviation (English) to one-fifth of a standard deviation (Algebra I).44

tests in four subject areas (Algebra I, U.S. History, Biology, and English II) by whether students earned any certification. The difference between IRC recipients and nonrecipients ranges from roughly one-eighth of a standard deviation (English) to one-fifth of a standard deviation (Algebra I).44

Figure 12. Students who earn IRCs are considerably higher achieving than their comparable peers.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. High school assessments include the Algebra I End-of-Course Exam (EOC), Biology EOC, English II EOC, and U.S. History EOC.

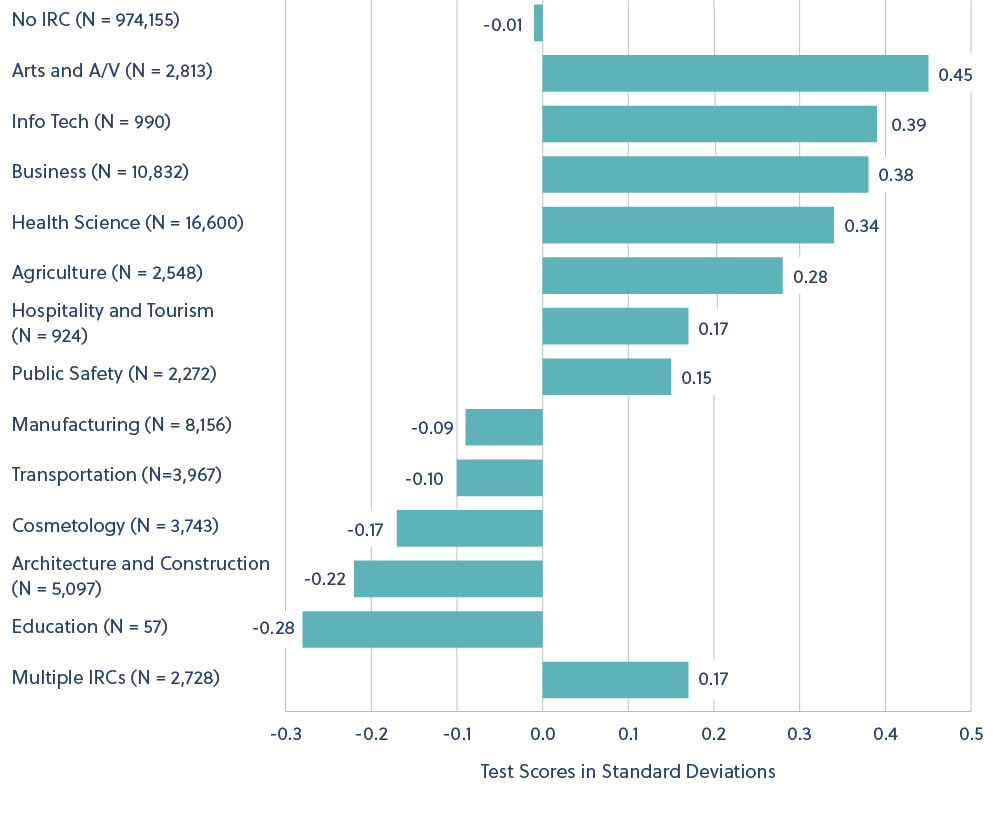

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. High school assessments include the Algebra I End-of-Course Exam (EOC), Biology EOC, English II EOC, and U.S. History EOC.Whereas IRC recipients are higher achieving on average compared to nonrecipients, this pattern varies markedly across IRCs. Figure 13 shows that students who received certifications in Arts and A/V, Information Technology, Business, Health Science, and Agriculture scored considerably higher (at least 0.25 standard deviations above the statewide average) on tested subjects, at times 0.40–0.50 standard deviations higher than their peers who did not earn IRCs. For context, the national Black-White test-score disparity is estimated to range from roughly 0.50–0.80 standard deviations depending on the specific grade level, assessment, and subject,45 suggesting that the test-score advantage is substantial for students who earned certain IRCs. In contrast, students who earned certifications in Education, Architecture and Construction, Cosmetology, and Transportation tended to score below average on standardized test scores (from 0.10 to 0.28 standard deviations). Once we control for students’ CTE coursework and other student characteristics, we tend to find positive relationships between test scores and essentially all IRC subjects (see Appendix A, Table A3 ). This suggests lower-achieving students may be more likely to pursue specific CTE programs, but among CTE participants, IRC recipients are higher achieving.

Figure 13. Student achievement varies markedly across IRC fields.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. Test scores are an average of the high school Algebra I EOC, Biology EOC, English II EOC, and U.S. History EOC.

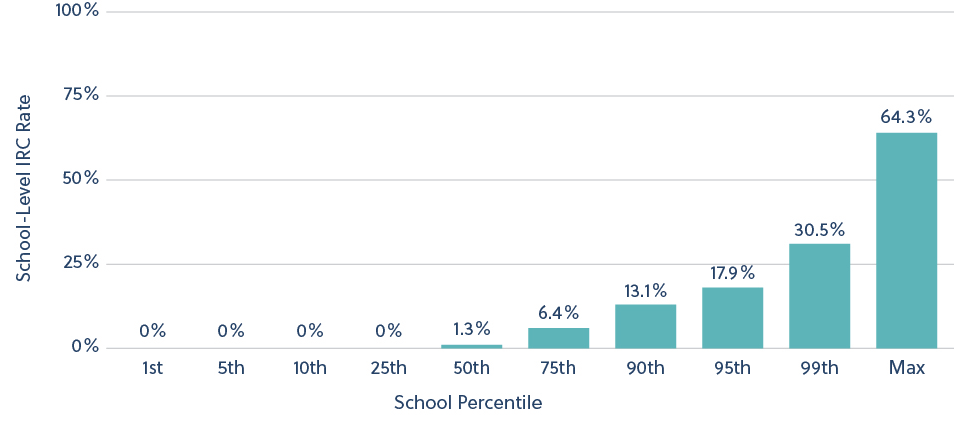

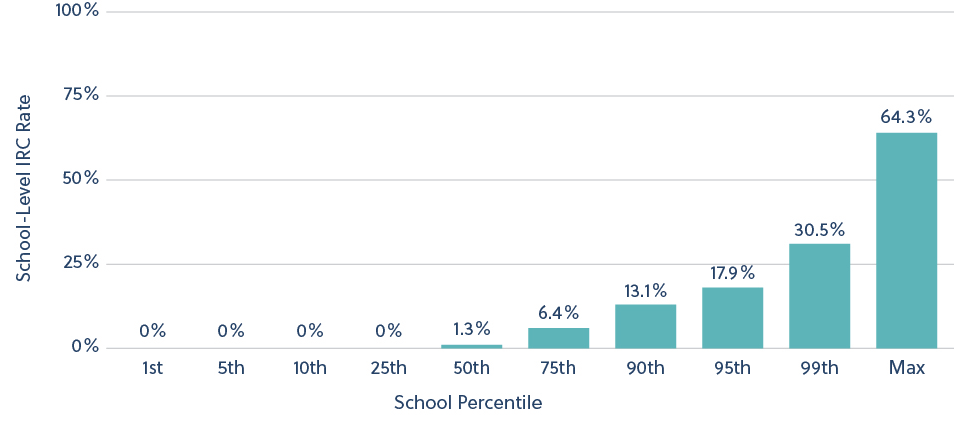

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019. Test scores are an average of the high school Algebra I EOC, Biology EOC, English II EOC, and U.S. History EOC.So far, we have examined how students’ demographic and academic characteristics relate to their likelihood of earning an IRC. As it turns out, what matters even more is which schools they attend. The substantial variation in IRC rates across high schools is highlighted in Figure 14. In many Texas public schools, not one student earned an IRC in any of the three years analyzed, and the median IRC rate (or the percentage of high school graduates who earned an IRC) for all schools was just 1.3 percent. In contrast, the top 1 percent of high schools (roughly twenty of them) had an IRC rate greater than 30 percent, and nearly two-thirds of the students who graduated from the one high school with the highest IRC rate in Texas completed a certification before graduating (we examine the role of school type below). Across all IRC categories, schools explain 65 to 75 percent of the variation in students’ likelihood of earning a certification.46 For context, studies using nationally representative samples of students estimate that schools explain roughly 15 to 25 percent of the variation in standardized test scores.47

variation in students’ likelihood of earning a certification.46 For context, studies using nationally representative samples of students estimate that schools explain roughly 15 to 25 percent of the variation in standardized test scores.47

Figure 14. Zero students earned an IRC at more than 40 percent of Texas high schools, but nearly two-thirds earned an IRC at the school with the highest rate.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,941 Texas public high schools with at least five high school graduates combined between 2017 and 2019. The percentage of high school graduates who earned an IRC between 2017 and 2019 was calculated for each high school in the sample.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,941 Texas public high schools with at least five high school graduates combined between 2017 and 2019. The percentage of high school graduates who earned an IRC between 2017 and 2019 was calculated for each high school in the sample.

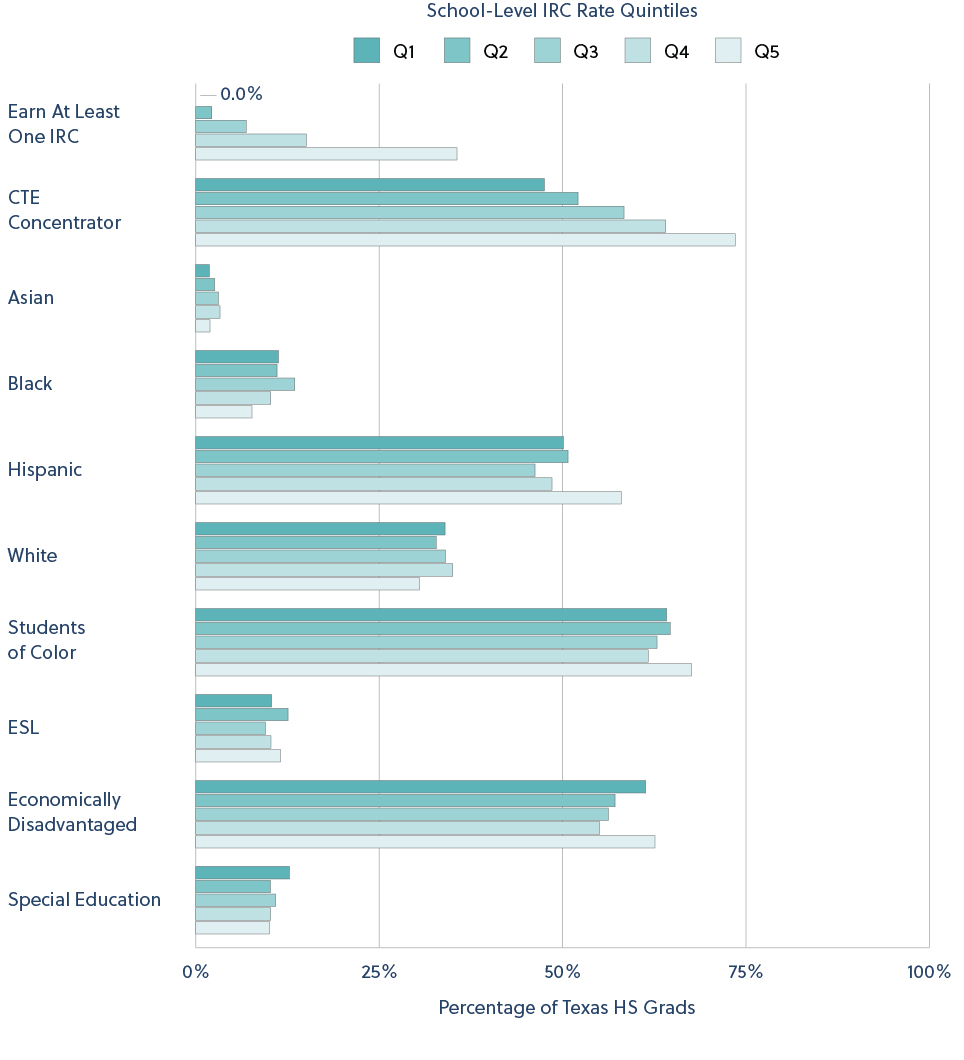

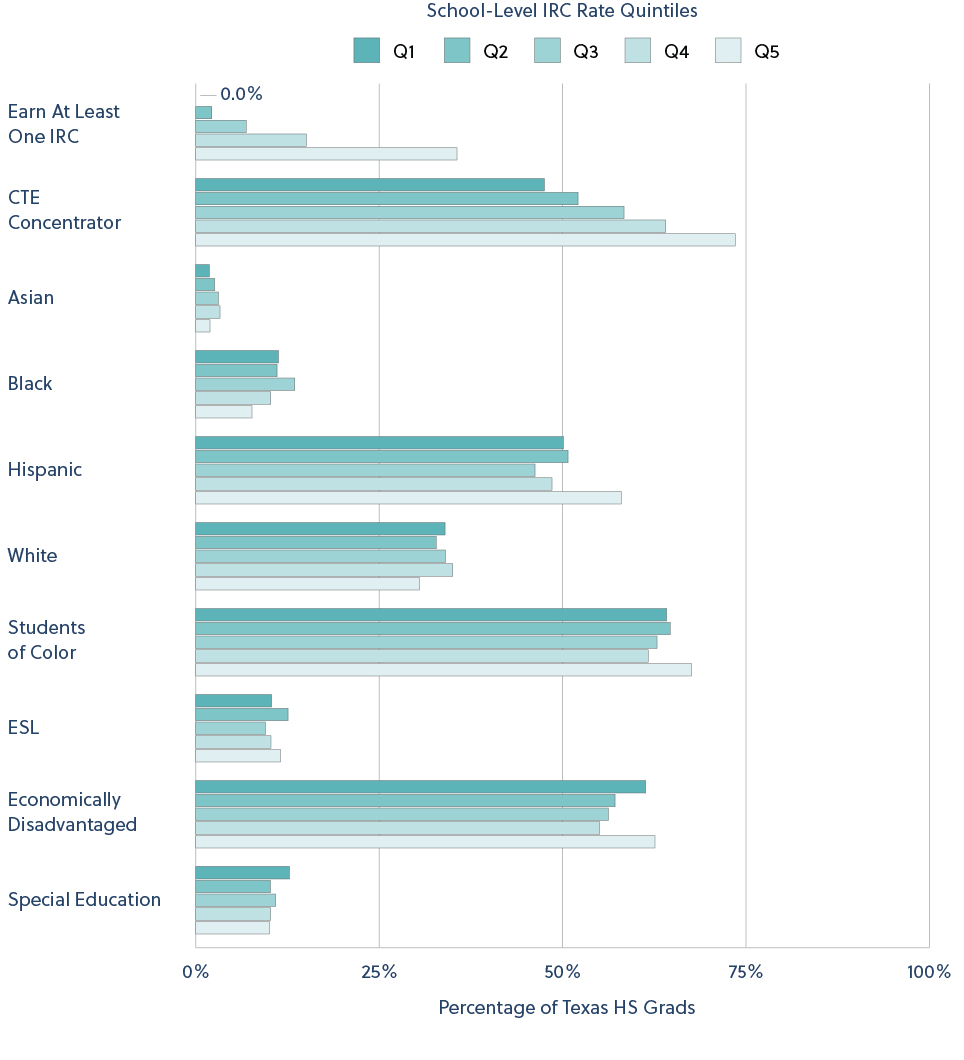

The particular school that students attend clearly matters to whether they earn IRCs, but why they matter is less clear. Figure 15 groups all high schools into one of five quintiles based on their IRC rate and compares the demographic characteristics of schools across them.48 While the IRC completion and CTE concentration rates vary markedly across schools, their demographic characteristics are similar. In more sophisticated statistical models (see Appendix A ), school variables such as size, demographics, and average test scores are only weakly related to students’ probability of earning an IRC.49

Figure 15. There is little demographic variation across five quintiles of schools based on their IRC rate.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on data from the TEA’s Texas Academic Performance Reports (TAPR) covering all 1,786 high schools included in the 2021 TAPR reports for the 2019–20 academic year. “Students of color” refers to Black, Hispanic, Native American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial students.

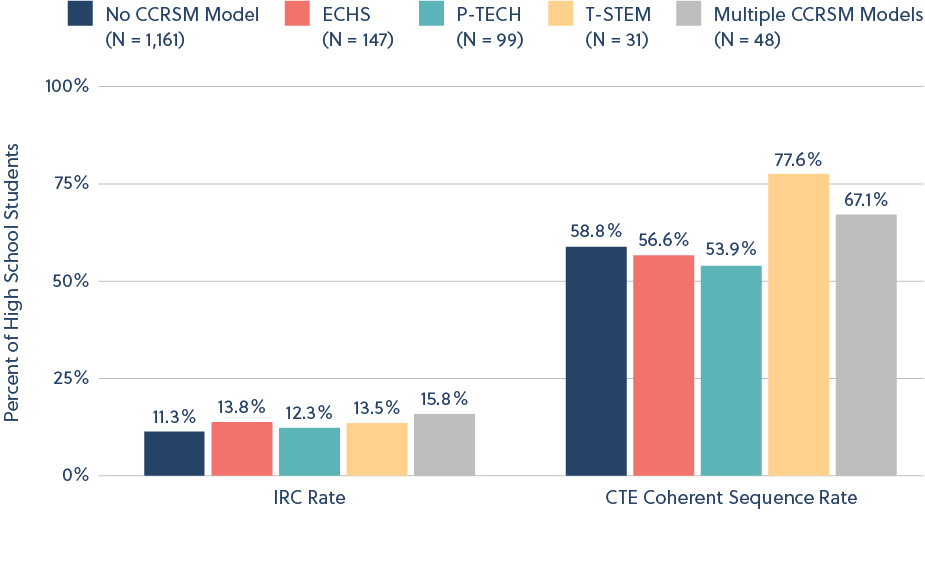

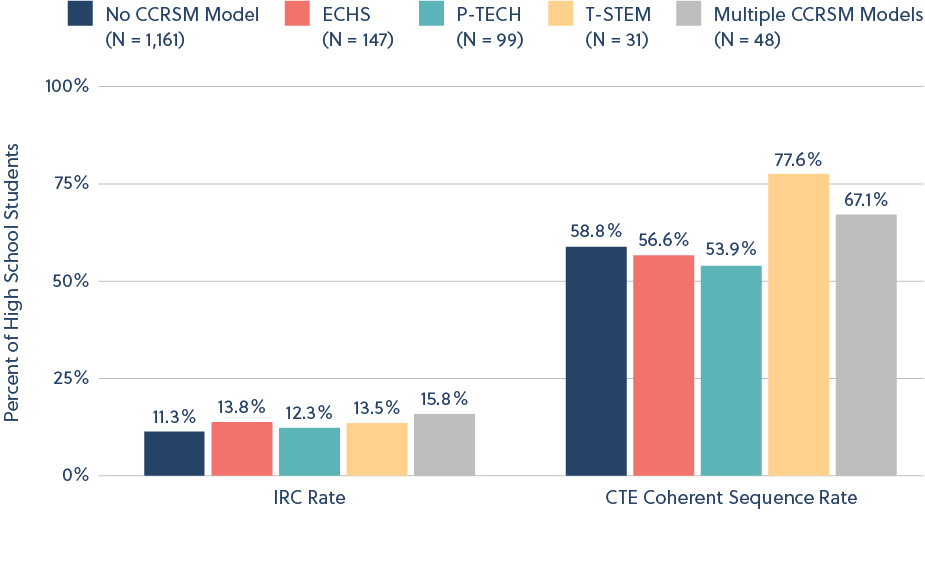

Note. Author’s calculations are based on data from the TEA’s Texas Academic Performance Reports (TAPR) covering all 1,786 high schools included in the 2021 TAPR reports for the 2019–20 academic year. “Students of color” refers to Black, Hispanic, Native American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial students.Finally, Figure 16 examines whether the school-level rates of IRC receipt and the completion of a coherent CTE sequence—one that typically includes increasingly rigorous courses50—vary relative to whether the school has adopted one of three Texas College and Career Readiness School Models (CCRSM),51 including the following:

- Early College High School (ECHS)

- Pathways in technology early college high schools (P-TECH)

- Texas science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (T-STEM) academies

The IRC rate for all school models investigated (including not having a CCRSM model) is roughly 11–13 percent, and schools that have adopted multiple CCRSM models have a rate of 16 percent. T-STEM academies have CTE sequence-completion rates considerably higher than non-CCRSM schools (77.6 percent vs. 58.8 percent), but ECHS and P-TECH schools actually have lower rates compared to non-CCRSM schools. Overall, while schools appear to be the most important factor in affecting students’ likelihood of earning an IRC, neither the demographic characteristics of the school nor the school’s adopted reform model relate strongly to the school-level IRC rate.52 We explore this finding further in the discussion section.

Figure 16: IRC rates are only slightly higher in high schools with specific school models designed to prepare students for college and career.

Note. CCRSM = College and Career Readiness School Models; ECHS = Early College High School; P-TECH = Pathways in Technology Early College Schools; T-STEM = Texas Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math Academies.

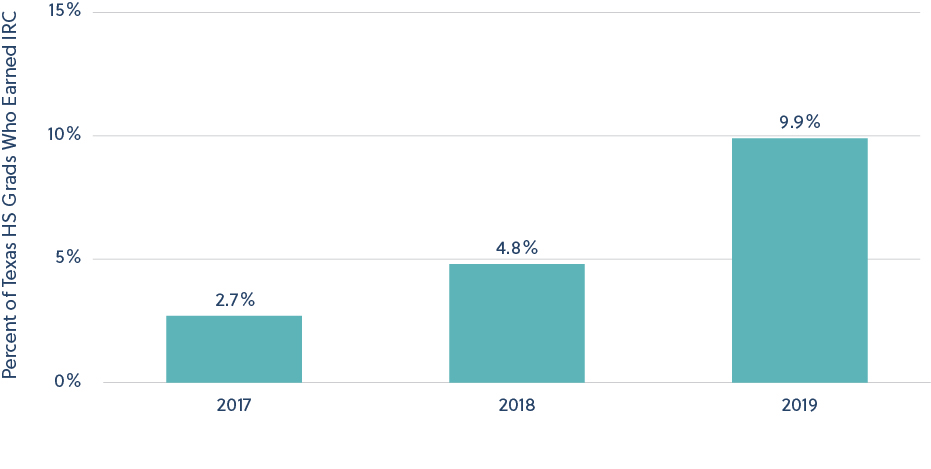

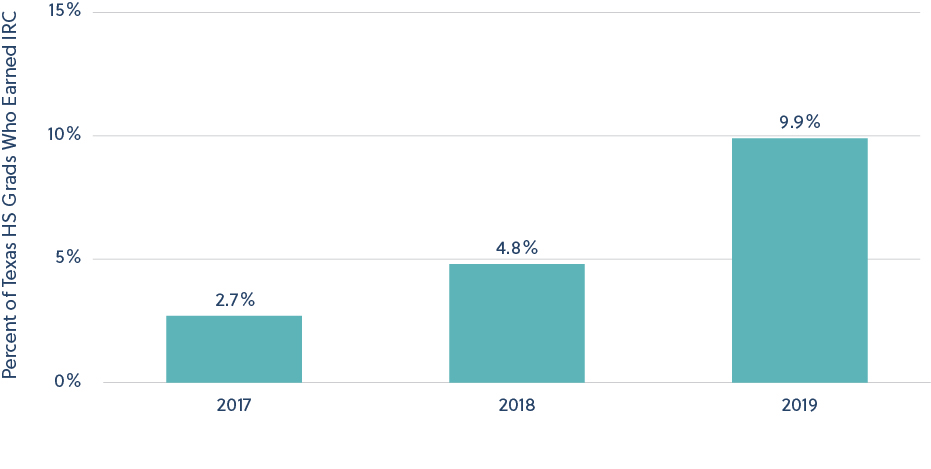

Note. CCRSM = College and Career Readiness School Models; ECHS = Early College High School; P-TECH = Pathways in Technology Early College Schools; T-STEM = Texas Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math Academies.The rate of students earning IRCs is growing in Texas. In 2017, only 2.7 percent of Texas high school graduates were recorded as having earned an IRC before graduating high school (Figure 17). This rate climbed to 4.8 percent in 2018 and more than doubled to 9.9 percent for the 2019 cohort of graduates. This considerable rise likely reflects not only an actual increase in students earning IRCs but also the expanded list of IRCs approved for funding and accountability purposes by state authorities and growing district capacity to accurately capture and report on the IRCs that students are earning (see “State policy context”).

Figure 17. The rate of high school graduates earning IRCs roughly doubled each year between 2017 and 2019

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 and show the percentage who earned at least one IRC.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 and show the percentage who earned at least one IRC.Finding 6: Health Science, Business, and Manufacturing dominate the top twenty-five most common IRCs.

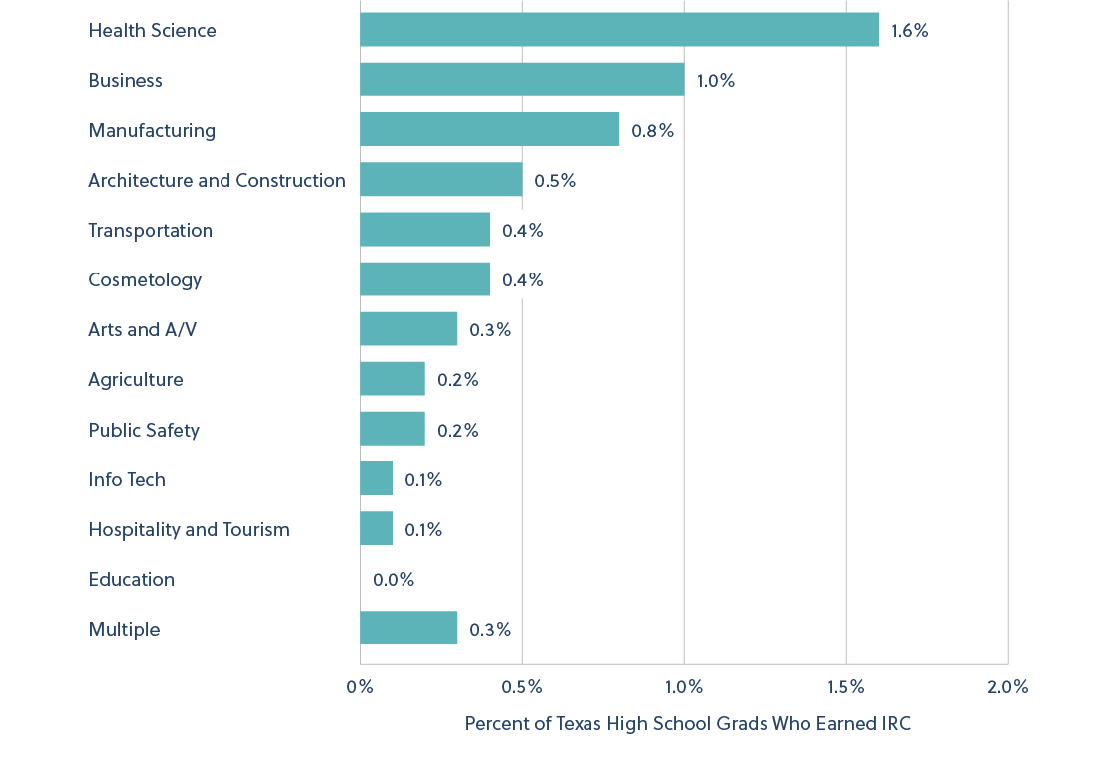

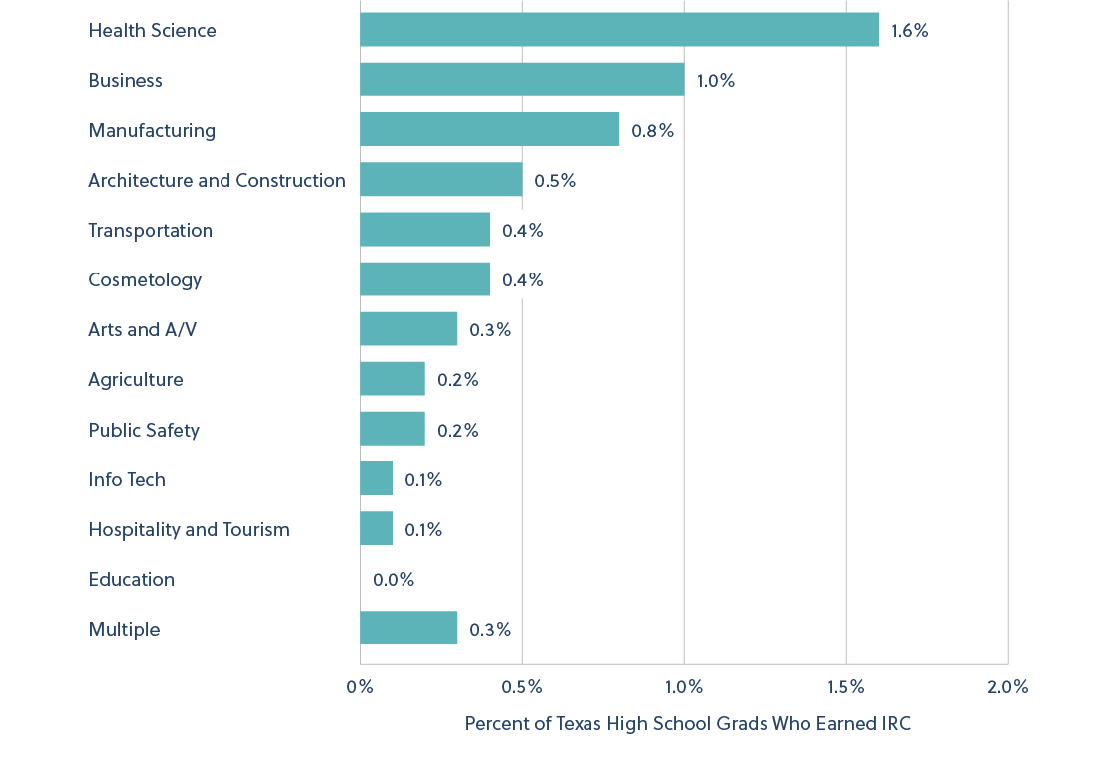

Figure 18 shows the rates at which students complete different types of certifications categorized by the CTE cluster to which they are most closely aligned. The categories are mutually exclusive, with students who earned certifications in more than one CTE area included in the “multiple” group. As shown, Health Science is the most popular IRC area, with roughly 1.6 percent of the sample earning an IRC in this area, more than the combined total of the seven CTE areas with the lowest rates of IRC receipt. Business and Manufacturing are the two next most common, with rates of 1.1 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively. Less than half of one percent of students earn all other categories of IRCs. Approximately 0.3 percent of high school graduates earned certifications from two or more different CTE clusters. Because only fifty-seven students across all three cohorts earned an IRC in the area of Education (mainly the Educational Aide certification), it is excluded from many of the prior analyses of student outcomes.

Figure 18: Health Science is the most common IRC field, followed by Business, with less than half of one percent of students earning IRCs in all other categories.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 and show the percentage who earned at least one IRC in each certification. Just 57 students earned IRCs in Education over the three graduating cohorts, and that figure rounds to 0.0%.

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019 and show the percentage who earned at least one IRC in each certification. Just 57 students earned IRCs in Education over the three graduating cohorts, and that figure rounds to 0.0%.

Table 3 shows the twenty-five IRCs with the largest number of students earning them across the three high school graduate cohorts. The Certified Nurse Aide/Assistant is the most popular IRC, with 7,354 students earning the certification; five other Health Science IRCs also make the list of the top twenty-five. Business IRCs are the next most popular, with all but one (i.e., QuickBooks) relating to certifications in Microsoft Office (see Appendix B for similar patterns in Massachusetts). Many of these popular IRCs are not highly technical and can be earned early in a CTE program. While Table 3 includes only twenty-five out of the hundreds of IRCs that students can hypothetically earn to be considered “college and career ready” by state policy, it comprises 60,184 of the 77,426 IRCs actually awarded (77.7 percent) during high school in Texas during the three years examined here. In contrast, the hundred least-popular IRCs all had fewer than seventy students earn them across the three cohorts.

Table 3. Health Science and Business have the most IRCs in the list of the top twenty-five most popular in Texas.

| Certification rank |

Certification category |

Certification title |

Student count |

|

1

|

Health Science |

Certified Nurse Aide/Assistant |

7,354 |

| 2 |

Business |

Microsoft Office Specialist Word |

5,496 |

| 3 |

Architecture and Construction |

NCCER Core Level I NCCER |

5,376 |

| 4 |

Business |

Microsoft Office Expert - Word |

4,368 |

| 5 |

Manufacturing |

AWS D1.1 Structural Steel Other |

4,344 |

| 6 |

Human Services |

Cosmetology Operator License PSI Testing Services |

3,806 |

| 7 |

Health Science |

Clinical Medical Assistant National Healthcareer Association |

2,717 |

| 8 |

Health Science |

Pharmacy Technician |

2,581 |

| 9 |

Health Science |

Phlebotomy Technician American Allied Health |

2,551 |

| 10 |

Business |

Microsoft Office Specialist Excel |

2,144 |

| 11 |

Health Science |

Certified EKG Technician National Healthcareer Association |

1,956 |

| 12 |

Arts and A/V |

Adobe Certified Associate Photoshop |

1,870 |

| 13 |

Manufacturing |

AWS D9.1 Sheet Metal Welding Other |

1,861 |

| 14 |

Transportation |

ASE Brakes Automotive Service Excellence |

1,442 |

| 15 |

Business |

Microsoft Office Expert - Excel |

1,379 |

| 16 |

Health Science |

Certified Patient Care Technician American Allied Health |

1,372 |

| 17 |

Agriculture |

Certified Veterinary Assistant |

1,322 |

| 18 |

Transportation |

ASE Maintenance Light Repair Automotive Service Excellence |

1,205 |

| 19 |

Manufacturing |

AWS SENSE Welding Level 1 American Welding Society |

1,153 |

| 20 |

Hospitality |

ServSafe Manager National Restaurant Association |

1,040 |

| 21 |

Business |

Microsoft Office Specialist (MOS) Master - 2016 |

1,006 |

| 22 |

Public Safety |

Noncommissioned Security Officer Level II |

1,000 |

| 23 |

Business |

QuickBooks Certified User |

971 |

| 24 |

Public Safety |

Emergency Medical Technician |

947 |

| 25 |

Public Safety |

IAED Emergency Telecommunicator |

923 |

Note. Author’s calculations are based on Texas administrative data covering all 1,034,882 high school graduates in the state from 2017 through 2019.

Implications

Implications

Clearly, this first-of-its-kind study is not the final word on the value of IRCs earned during high school—particularly because we were only able to follow students’ education and workforce outcomes for the first year after their graduation from high school. Yet there is much worth contemplating herein about how industry-recognized credentials influence student outcomes. Below are four implications that merit attention.

First, IRCs earned while in high school are mostly a positive for the students who earn them, but they are far from transformational.