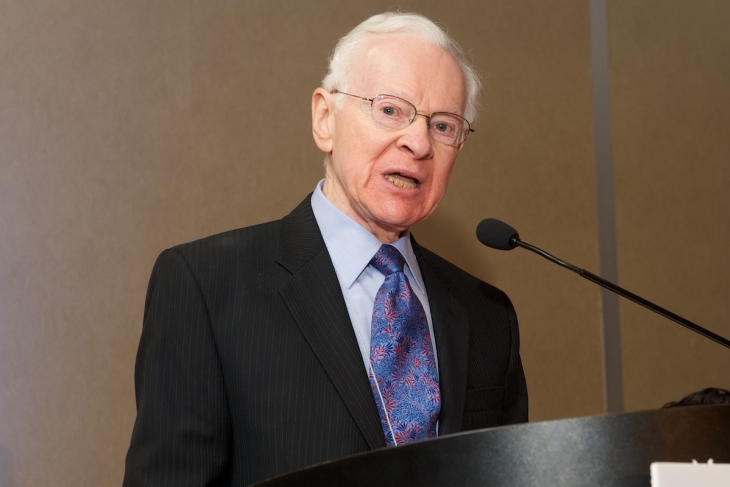

When Emerson Elliott passed away the other day at eighty-nine, surrounded by his loving four-generation family, one might simply say adieu and thanks to a capable and dedicated career federal civil servant—which he surely was. But that’s not the whole story and we—education folks especially—are in his debt for so much more.

That certainly goes for me. Emerson and I interacted off and on for half a century. I met him in 1969 when I was a junior White House staffer with some responsibility for education within the domestic policy team and he—just fourteen years out of Albion College but already a twelve-year veteran of the Bureau of the Budget (now OMB)—was in charge of the federal education budget. (His boss at the time was the late Dick Nathan, another distinguished public servant with whom I had the honor of crossing paths on multiple occasions.)

I was a callow youth. Em knew what he was doing. And like senior OMB careerists were (and are) supposed to, he participated fully in working groups and policy powwows, offering his best judgment as to what might work best to accomplish some desirable end, how much it might cost, what’s feasible and what’s not, what would need to change, and so on. Professional and neutral, to be sure, but also informed, insightful, and wise.

We would re-engage in a big way a decade and a half later, but during that interim, Emerson moved to the old Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, then the new Department of Education (and also took a breather for two years at George Washington University). Here’s a bit from his resume:

November 1982 to 1984: Director, Issues Analysis Staff, Office of the Under Secretary, Department of Education

June 1981 to October 1982: Director, Planning and Evaluation Service, Department of Education

February 1981 to May 1981: Consultant to the Secretary on legislation and Department organization

May 1979 to January 1981: Director, HEW School Finance Project

March 1978 to April 1979: Director, Educational Staff Seminar, George Washington University

August 1977 to February 1978: Practitioner in Residence, Institute for Educational Leadership, George Washington University

August 1972 to July 1977: Deputy Director, National Institute of Education.

May 1972 to July 1972: Associate Deputy Commissioner for Management, Office of Education, HEW

As you can tell from the “director” titles, Emerson had emerged as a leader, not just a doer or staffer.

We had various small-scale dealings during that period, but were thrown back together in 1985 when I joined Bill Bennett at ED as assistant secretary, heading what was then called the Office of Education Research and Improvement (OERI), precursor of today’s Institute of Education Sciences. As we put together a team to run this section of the Department, we realized both that it needed a full-scale reorganization, and also that its statistics unit—the National Center for Education Statistics—was sick: underfunded, neglected, abused, sluggish, underproductive, and nowhere near what had been envisioned as much as 120 years earlier when Congress created the original “department of education” to “gather statistics and facts on the condition and progress of education in the United States and Territories.”

Two years after A Nation at Risk, the dearth of up-to-date, high-quality education data was a serious problem for the nation. Bennett knew it, I knew it, Em knew it—and an expert panel declared that either NCES needed a total overhaul or should be put out of its misery.

Emerson at this point assumed a dual role, first as major advisor and strategist on a big reorganization of the whole of OERI (which Congress eventually okayed), and also as the first modern “Commissioner of Education Statistics,” responsible for directing NCES. But it was more than directing. It was also rebuilding that weak entity into a semblance of today’s multi-dimensional federal education statistics agency.

With Secretary Bennett’s blessing (though to the consternation of the heads of OERI’s other four units), we directed pretty much every extra appropriations dollar we could get into the NCES budget. But that wouldn’t have solved the problem without Em’s solid, focused, diplomatic-yet-firm leadership of the place, which inevitably extended beyond the agency itself into deft if usually quiet dealings with colleagues, Congress, and innumerable keen-eyed (and often hungry) outside constituencies.

While doing all that, he also served as an indispensable member of the little brain trust (along with Mike Kirst and myself) that did the heavy lifting for the Alexander-James task force that reinvented NAEP to become the semi-independent and generally respected arbiter of “how good is good enough” in the achievement of American K–12 students and the honest rapporteur of their performance at the national and state levels (and now in a number of big cities, as well.)

I stayed at ED into 1988, but Emerson remained NCES Commissioner until 1995, when, still in his early sixties, he retired from the federal civil service, having accumulated by then pretty much every prize and honor available to top performers in that line of work.

Whereupon he embarked on what amounted to a second career of research, writing, consulting, and advising for a host of education-related organizations, particularly the teacher-ed accreditation body known as NCATE and its successor, the Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Preparation (CAEP).

But there was much more. To quote again from his resume (which goes only to 2012):

Since leaving the Federal Government in 1995, consulting and advisory memberships have included: the U. S. Department of Education, National Educational Research Policy and Priorities Board; National Academy of Sciences panels on Bureau of Transportation Statistics, a feasibility study for a Strategic Education Research Program, the Board on Comparative International Studies in Education (chair), and a workshop on national education indicators; the Advisory Committee on Research and Development for the College Board; the Science Resources Studies Advisory Committee of the National Science Foundation; the advisory panel for “Measuring Up” indicators published by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education; an evaluation of the Delta Cost Project for use by its Board to make long term strategic decisions; and education indicators for the State of the USA key national indicators project.

Most recently, Em and I reconnected in 2020 as I embarked on a book about NAEP’s history and current challenges and sought to consult his memory on various issues. Though well into his mid-eighties and soon headed toward what would become his final illness, he responded promptly, generously, and far beyond my expectations. He basically read every word of my manuscript, especially the history parts, amplified and corrected the facts, engaged respectfully on a number of touchy issues, and even used this occasion to rethink some longstanding points of tension between the “NAGB view” and the “NCES view” on key topics such as NAEP’s “achievement levels” (basic, proficient, advanced). It’s scarcely surprising that Emerson’s name appears on multiple pages of that volume, as well as in the acknowledgments.

I can’t claim that we were ever close friends. But I do assert, without fear of contradiction, that we were fortunate, as education folks and as Americans, to benefit from six decades of the highest-quality professionalism, conscientiousness, and near-perfect instinct for what would be best and work best and yet be doable from this remarkable public servant. May he rest in peace.