When schools resume instruction this fall, most students will have been absent from the classroom (and without direct access to teachers, peers, and other school-based supports) for upwards of six months. In addition to addressing significant learning loss, school leaders will need to carefully consider how to address students' social, emotional, and mental health needs when schools reopen—whether for remote, in-person, or hybrid instruction—in the fall.

If we are to survive the stress and uncertainty of this year’s school reopenings, we are going to have to learn how to lead from a place of grace and empathy. None of this is easy. There are not any good, let alone perfect, options. The conditions on the ground are changing daily, and the personal circumstances of each family—whether teacher or student—are different.

And so is their tolerance for risk.

The president, governors, and education leaders are obviously free to say that the goal is to get all students back in their school buildings at the start of the year. But they can’t force parents to send them. Unless school districts want to risk a mass exodus of families, a robust distance learning program will need to be on the menu of options.

Some parents, especially those zoned to the most decrepit and poorly maintained buildings, do not have confidence in their schools’ ability to keep their children safe. They understandably say, “If I didn’t feel like they were safe in school before the pandemic, why would I feel differently now?”

That statement resonates most with parents and teachers assigned to schools that have never been clean, well-maintained, or even structurally sound. But for parents who have never feared for their children’s safety in school or are unaccustomed to deplorable conditions, it’s hard to relate.

There are parents, some of whom are also teachers, who are frightened by the thought of their children contracting the virus; others, for whatever reason, are less worried. Neither person is right or wrong. They just see an extremely complex, emotional, and unprecedented challenge differently.

Children across America suffer from myriad health conditions that can make any virus, let alone Covid-19, scary and dangerous. Perfectly healthy teachers have parents in their nineties who live in their homes. As one Central Falls teacher shared with me, “I touch my ninety-year-old father’s food every day.”

Another husband and wife worry that her breast cancer treatments leave her too vulnerable for her children to be bringing germs home from school that could lead to her contracting the virus.

None of these fears are unreasonable or irrational. It is wrong and even cruel to imply that they are.

And it is equally wrong to imply that the parent or teacher who wants to go back to school somehow wants to “kill children.” The statement is so ridiculous and inflammatory that it barely warrants a response. Distance learning was a massive challenge for a huge swath of kids and families, and there is plenty of evidence that getting back to school must be an urgent priority.

Each option has benefits and trade-offs, and the calibration of those will vary greatly among parents, administrators, and school staff for lots of different reasons.

For better or worse, we live at a time when anyone can find a link to an article or website that supports their preferred side of the argument. People on all sides wield internet links like weapons, often to demean their opponents instead of persuading or solving problems. It’s sad to see that happening between neighbors and friends during a time that is already so hard.

Have we really decided that it’s acceptable to shame a custodian or bus driver because they are afraid for their health? When I was a high school student, and later a teacher at my alma mater, we had a really grumpy main office, run by women in their sixties and seventies. These ladies hardly saw it as their life’s mission to brighten your day or tend to you with top notch customer service (though their hearts were tender once you broke through). As I listen to the conversations about schools reopening, people like them are far too often invisible. And while I absolutely support centering the reopening conversation around what’s best for students, I do not support erasing all the people who work in schools and are at much higher risk of getting sick. It lacks humanity.

I have spent a lifetime believing that we are called to care for the sick, the vulnerable, and the weak. And that is very hard to square with what is coming out of the mouths and keyboards of far too many people, whether it be from a Rose Garden podium, parent groups on Facebook, or influential commentators on Twitter.

We need to let people land where they land and, frankly, butt out of other people’s business. If we want to be part of making the fall better for ourselves and others, our business is to learn as much as we can about the options being offered by our districts and elsewhere if we are considering alternatives. Our business is to do what we can to close the digital divide and ensure that all students, whether we know them or not, have access to broadband internet. Our business is to support—and not judge—our friends and neighbors who are struggling to figure out how to make the fall work. If we have knowledge that could help them, we share it. If we have a network of people who could offer suggestions or wisdom from their experience, we connect them. If there are bills in Congress or our state legislatures that would help the parents and students who need it the most, we make calls and write emails to try to get them passed.

Parents will and should do whatever they believe best serves and protects their children and their family. That may mean wanting to ensure that their child doesn’t suffer from the social isolation they felt in the spring, or it may mean minimizing exposure to Covid-19 by keeping them home.

Let’s respect their decision.

Editor's note: This was first published on the author's blog, Project Forever Free.

- In the discussion of whether and how to reopen schools in the fall, the spotlight falls (sort of) on private schools in central Ohio. Two schools—one Catholic high school, one secular K-12 school—which historically have had more space than kids—are the exemplars and lead the coverage about fully in-person classes. That’s the plan for now. A third school, a smaller Catholic high school, does not have the space for distancing its students and thus is (for now) planning on split in-person sessions. We don’t know what the students in this latter school will be doing for education when they are not attending in-person, but let’s hope for tuition’s sake that it’s something better than the poor distance learning substitute that Fordham’s Chad Aldis reminds us about. But you know what would have been a good place to start? A review of what those private schools did this past spring in regard to distance learning. I happen to have a deep personal knowledge of this topic in regard to one of these schools, but my phone has, as it has always done, remained silent. (Columbus Dispatch, 7/26/20) Speaking of which, we finally got some coverage of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’ visit to suburban Columbus last week which actually discusses the main topic of the event: private school choice. Timely, even when appearing days after the fact. (Ohio Capital Journal, 7/27/20)

- “No teacher should go back to the classroom without one… This is truly the answer.” The good doctor is quoted talking about face shields here, as he and his foundation determined during the SARS epidemic back in the day. Personally, I think it’s great that he is such an adorably nerdy guy (that bowtie!) so that his message should be readily accepted without any hesitation at all. (Cincinnati Enquirer, 7/26/20)

- No nerdiness here. “Summer is the time for education leaders to learn from the lessons of last year and improve online learning for all students,” writes Ohio Excels president Lisa Gray in this opinion piece. “The key,” she concludes, “is planning now for what is likely to come.” (Lima News, 7/24/20)

- Yellow Springs Exempted Village Schools is the latest to announce its classes will be fully online for first quarter of the upcoming school year. There are some details about the hourly requirements and a sketch of the schedule in this article. More to come, I’m sure. "We’ve learned so much about what it means to be online,” said the superintendent during the special Zoom-based school board meeting this weekend, “and how we can shape experiences so they’re better for both students and families.”. (Dayton 24/7 Now, 7/26/20)

- Cleveland Metropolitan School District, the pioneer among school districts going fully remote for at least the first part of the school year, cancelled all fall sports too. “If it’s not safe to be in school, it’s not safe to be on the playing fields either,” said district CEO Eric Gordon. While that sitch seems like a no-brainer to me, I kinda get the impression that CEO Gordon actually means it to be a pointed and unequivocal clarification of what should probably have been clear sooner since his athletic department apparently aims to continue summer athlete workouts until the official OHSAA summer season ends on July 31. For some reason. (Cleveland.com, 7/24/20)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Assessing parent satisfaction with distance learning

ExcelinEd recently posted a meta-analysis of several surveys of parent satisfaction with the distance learning their children experienced this spring during pandemic-mitigation school closures. Charter and private school parents were consistently more satisfied than those in traditional district schools and the data point to stronger family engagement before the pandemic—often a hallmark of schools of choice—as a strong factor in these findings.

Preliminary school reopening plans in Dayton

Kudos to Jeremy Kelley of the Dayton Daily News for taking the effort to include Dayton Early College Academy in its look at proposed school reopening plans in the region for the fall. DECA has thus far announced a plan to have half of their students attend in-person classes on Mondays and Tuesdays and the other half on Thursdays and Fridays.

Detailed discussion in Cleveland

Two charter school teachers were included in an hour-long discussion on public radio in Cleveland regarding their schools’ potential reopening plans. Worth a listen.

Switching gears

The Washington Post suggests that President Donald Trump would like to make education—and school choice issues in particular—a prominent theme in the presidential race this year. Charter school discussion here focuses on former Vice President Joe Biden’s recent vocal opposition.

The Covid-19 pandemic has further exposed the inequities that have long existed in K–12 education system. School closures due to the outbreak are particularly hurting low-income families and communities, and will likely exacerbate existing academic gaps, including the “gifted gap”—the difference in participation in gifted programs between low-income higher achievers and their more affluent peers. The longer schools remain closed and states struggle to devise re-opening plans, the greater the potential harm to bright students from low-income backgrounds.

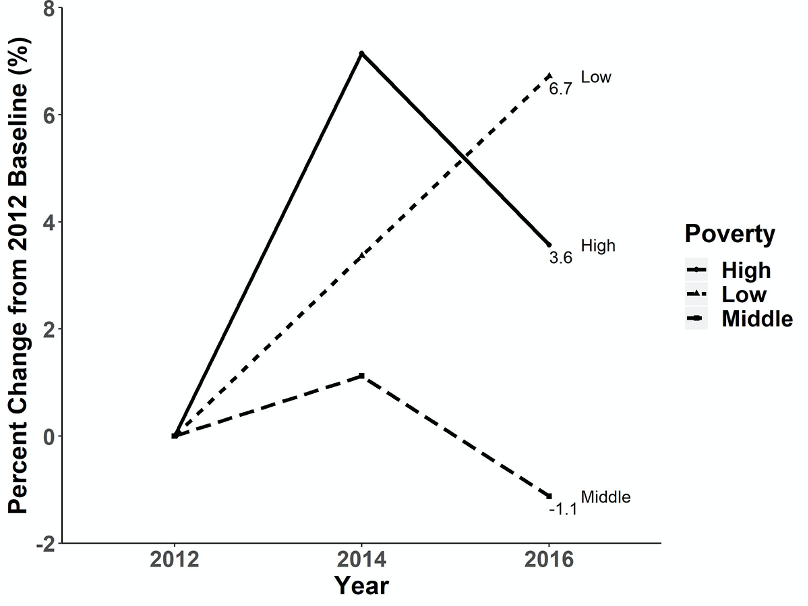

In 2018, when Adam Tyner and I published our report Is there a Gifted Gap?, the gap was already significant. We found that students in low-poverty schools participated in gifted programs at twice the rate of students in high-poverty schools. And in a recently published article, we found that the gaps have been growing. As Figure 1 shows, between 2012 and 2016, gifted participation in affluent schools increased by 6.7 percent, while only increasing by 3.6 percent in their less affluent counterparts. Middle-poverty schools saw an overall decline in gifted participation.

Figure 1. Percent change in gifted program participation between 2012 and 2016, by school poverty level

If high-poverty schools are not encouraging and cultivating young talent through high quality educational programs tailored to their achievement level as much as low-poverty schools, it may help explain why students from low-economic backgrounds continue to fall behind their wealthier peers

Sadly, we know that these gifted gaps are not primarily caused by differences in academic abilities. Research has shown that even among students with similar achievement and other background characteristics, higher-SES students are more likely to receive gifted services than lower-SES students, even within the same school. The problem is the system, not the students.

Our current study also shows that Black and Hispanic students continue to be statistically underrepresented in gifted programs. We did, nevertheless, find that the share of Hispanic students participating in gifted programs rose by 0.5 percent and 5.8 percent in all schools (low, middle, and high-poverty) and high-poverty schools, respectively. These increases can be attributed to an increase in the overall proportion of Hispanic students in our samples over the study period. For instance, in high-poverty schools, the proportion of Hispanic students increased from 36.3 percent in 2012 to 41.5 percent in 2016.

The question I normally get is, “Why should we care about high ability students?” As Checker Finn and Brandon Wright put it in their book, Failing Our Brightest Kids, “At the forefront of creation, invention, and discovery are—nearly always—the society’s cleverest, ablest, and best-educated men and women.”

Given our current pandemic and systematic crackdown of legal immigration by the current administration, it is perhaps more important now than ever that schools cultivate and nurture homegrown talents of all students, including high achievers. To prepare for the next global pandemic, we must also prepare the next brightest medical doctors, scientists, engineers, and policymakers.

To improve gifted participation and representation of bright students regardless of background or socioeconomic status, policymakers and administrators at the local levels must heed the research evidence that outlines strategies to combat the “gifted gap.” The good news is, we can achieve equity in these programs without compromising rigorous standards.

- We’ll start today with some unequivocal good news. That consists of another awesome look at the opening of I Promise Village in Akron this week. Be sure to look at all the pictures and watch the video too. (Akron Beacon-Journal, 7/22/20) And it also consists of kudos to the Franklin County Commissioners for funding and to COSI Columbus for creating and distributing hands-on science learning kits to kids in the county. “We believe that education is the great equalizer,” said a science museum spokesman. “Especially in the middle of a pandemic, we don’t want our youth to get left behind. These kits will provide them with critical distance learning, fun STEM content that they’ll have for the entire week through these learning lunch boxes. So together we are feeding lives, feeding hungry lives and feeding hungry minds.” Nice. (Columbus Dispatch, 7/22/20)

- Then we move on to what can be termed YMMV good news. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos was in DeBuckeye State yesterday—live and in person at Tree of Life School in suburban Columbus. We have four pieces of coverage that, eventually, tell the whole story for you. This preview story lays out the purpose of the event—talking about private school choice—amid a bunch of other stuff that the event was not supposed to be about but ended up being about anyway. This is the only coverage I could find that actually includes full video of the event. So there’s that. (10TV, Columbus, 7/23/20) The Statehouse News Bureau “coverage” of the event merely covered the griping of one person who wasn’t invited but wanted to be (?) so as to have some lead time to loudly and publicly refuse to attend for whatever her stated reason would have been. A great loss indeed. (Statehouse News Bureau, 7/23/20) The local public media “coverage” of the event merely covered griping by someone who wasn’t invited and wouldn’t likely have attended about someone who was invited and did attend. Exhausting. (WCBE-FM, Columbus, 7/23/20) And then there was the local TV news outlet that actually covered the event. You know? Their actual job. (WCMH-TV, Columbus, 7/23/20)

- Even the outlet providing proper coverage of Secretary DeVos’ visit neglected to discuss the actual point of the event—private school choice. They instead focused on the au courant topic of school reopenings amid an ongoing pandemic. “Education is a promise that we make to students and their families and we need that promise actually kept,” DeVos told the gathering in that regard. “We want to make sure that students can continue learning in a full-time, full-on, high expectation environment. We think it’s important that schools look at all of their students and know that for some families, if the right choice and the right situation is five days full-time in-class learning, then that really has to be an option for families.” DeVos also addressed the topic of online learning, saying, “These are formative years and we know that for many students, 100 percent online learning simply isn’t tenable.” But reality is clearly dictating an online option for families in schools and districts across the state. Cleveland Metropolitan School District announced this week that the first nine weeks of the delayed-start school year would be entirely online this fall. (Cleveland.com, 7/23/20) Bowling Green City Schools announced the same, although their timeline may be a bit shorter. (13ABC-TV, Bowling Green, 7/23/20) Down the road, Rossford Exempted Village School District opted for a hybrid model, including a fully online school for families who want it. This last bit was only approved after residents were assured that it wasn’t run by one of those dastardly charter schools. Phew. (Bowling Green Sentinel-Tribune, 7/24/20) Tiny, bougie Grandview Heights City Schools have developed not one but two different online models for their 2020–21 plans. The hybrid model will be locally run (in conjunction with a half-day, every day, in-person schedule) while the fully online school will be outsourced to Florida Virtual School to run. Also not a charter school. (ThisWeek News, 7/22/20)

- Finally this week, under the heading of schadenfreude, the rewriting of school history in Lorain begins. What’s the topic? Does it even matter, really? (Elyria Chronicle, 7/24/20)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

In its recent guidance on reopening schools, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) noted that the Covid-19 pandemic has revealed and exacerbated “deeply rooted social and educational inequities.” Sadly, that’s exactly right. While many of these inequities aren’t new, the pandemic has made them more obvious—and more damaging—than before.

Consider connectivity. In today’s increasingly digital world, lack of internet means lack of access to job listings and application portals, education opportunities, telehealth services, and myriad other necessities. Internet access is no longer a luxury. It’s a public utility. And only the high-speed version is truly functional.

Unfortunately, nearly one million Ohioans, residing in more than 300,000 households, don’t have access to high-speed internet. Cleveland is the fourth worst-connected city in the nation—44 percent of homes have no broadband service beyond data plans on cell phones, and 40 percent of families with students enrolled in the city school district don’t have an internet connection. Cleveland isn’t alone, though. Nor is it just a city problem. Broad swaths of the state, many of them rural, have no broadband access at all.

These numbers were worrisome even before the pandemic. But when schools were forced to take education digital this spring, the seriousness of the problem became more apparent. Remote learning efforts have been far from perfect. But for students who lack internet or a workable device, even limited educational opportunities have been out of reach. The learning loss implications could be dire, especially for the low-income students who are least likely to have decent connectivity.

Due to the pandemic’s unpredictable nature, many schools expect to offer remote or blended learning as they reopen in coming weeks. But the connectivity shortfalls have not disappeared. If the state really believes that each child deserves access to “relevant and challenging academic experiences and educational resources,” then it’s time to do something about connectivity. But what?

Let’s understand that connectivity—for students in particular—is a two-pronged problem. When experts say students lack it, they don’t just mean access to high-speed internet. They also mean access to internet-enabled devices that are conducive to school work (smart phones don’t count). This two-pronged problem requires a two-pronged solution.

In terms of broadband access, the sheer size and cost of the problem lends itself to state-level solutions. Fortunately, Ohio leaders recognized this long before Covid-19 arrived. In December, the governor’s office released The Ohio Broadband Strategy, which outlines the administration’s plan to bring high-speed access to every Ohioan. It contains several goals, including implementing a statewide grant program to bring internet to underserved areas, encouraging investments in innovative technologies, and developing digital literacy programs. One of its most promising goals is to identify a state agency that could house a broadband office charged with centralizing oversight of internet expansion. Such an office could and should make it a priority to ensure that all of Ohio’s K–12 students have internet access.

A few weeks ago, Lieutenant Governor Husted told reporters that the pandemic has “increased the importance” of these strategic efforts. That’s good news. But state leaders also need to bear in mind that there are places—like Cleveland—where limited access is a matter of cost to families, not of broadband presence. The pandemic has triggered plenty of philanthropic efforts to provide free or affordable internet access to low-income families. The state could step in and help make these affordability efforts more widespread, comprehensive, and permanent.

When it comes to devices, on the other hand, solutions should be decentralized. Device disparities vary considerably between communities, and even within them. It’s best to let local leaders continue to assess the scope, identify solutions, and implement them. Several Ohio districts are already one-to-one, meaning that each student is assigned an internet-enabled device at the start of the school year. Many other districts began distributing devices during school closures this spring. Going forward, these efforts should continue and expand. They will likely require financial support from the state, philanthropy, and businesses.

The pandemic has shed a brighter light on Ohio’s large and complicated connectivity problem. It’s good news that there are state level plans and community-led initiatives to eliminate disparities. But it’s important that these efforts don’t stop when the pandemic loosens its grip.

- We continue our theme of low-quality clips this week. The Dispatch had guest commentary pieces today, both trying to answer the question what will it take to reopen schools in the fall? First up was the answer from a medical/health angle. The author is a pediatric critical care physician. (Columbus Dispatch, 7/22/20) The second piece tries to answer the question from the perspective of money. The author is a researcher for Policy Matters Ohio. (Columbus Dispatch, 7/22/20)

- Here, also, is a radio show from yesterday looking at the question from the perspective of teachers in Northeast Ohio, including two from local charter schools. (IdeaStream, Cleveland, 7/21/20)

- School open or school closed, nothing can apparently stop the opening of the I Promise Village in Akron. The supportive housing offshoot of the I Promise School will be welcoming its first families this week. Check out the photos. It is amazing. (WKYC-TV, Cleveland, 7/22/20)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

School funding mechanisms are the largest and perhaps most obvious levers for policymakers to pull when attempting to reform how education dollars are distributed. To wit, a new research report from a trio of scholars tells us that there were a whopping sixty-seven major school finance reforms (SFRs) across twenty-seven states between 1990 and 2014. From court ordered reforms to legislative initiatives to combinations of both, SFRs varied in scope and operation. In response, some states changed their funding formula, others changed how much “weight” they gave to particular student needs, still others looked to new funding sources. But what was the result of all of this change?

The study examines state-level variation in the effect sizes of SFRs on school spending among low- and high-income districts within states, as well as variation in the types of resources purchased. Analysts looked at whether the reforms improved outcomes on average in the poorest districts in the state and whether the reforms were progressive in nature: whether bottom-tercile districts benefited more relative to top-tercile districts. Using district-level household income from the 1990 census, they computed the average level of resources in the bottom and top terciles of the income distribution. To estimate these state-by-district income impacts by tercile, they used the recently-developed “ridge augmented synthetic control method.” The simplified (!) goal of this method is to obtain more equivalent matches between groups before the SFRs occurred. Ultimately, the researchers compare the twenty-seven states with SFRs—as their own individual case studies—to a single control group composed of the remaining states without SFRs.

Treatment begins the year after the reform is legislated or ordered. The researchers use data from the F-33 federal forms submitted by the SFR states that include total revenue; total expenditures; and subcategories of expenditures including instructional staff support services, capital outlays, and teacher salaries for school years 1989–90 to 2013–14. They also utilize full-time equivalent (FTE) student counts as reported in National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data.

On average, across all SFRs, expenditures increased by 6 percent in low-income districts and 1 percent in high income districts. Overall, low-income districts increased spending in greater amounts relative to high income districts after the reforms, meaning that the SFRs had progressive effects on school resource allocation. Across low-income districts, a 10 percent increase in total spending corresponds to a 19 percent increase in capital spending and 6 percent increase in salary spending.

When they examined heterogeneous effects, however, the researchers found variation in how this plays out. Among low-income districts, ten states increased spending, two decreased spending, and in fourteen states, there was no change in low-income spending. Comparing low- and high-income districts, they find that a 1 percent increase in spending among low income districts is associated with a 0.46 percent increase in spending among high income districts. Further, as mentioned, results show that low-income districts boosted their spending on capital expenditures—renovation, repair, or new construction of facilities—rather than on other classroom-related items such as increasing teacher salaries or reducing class sizes.

Importantly, the researchers find suggestive evidence that many states without SFRs also increased spending among low income districts at the same or even higher levels than states that enacted SFRs. They speculate that spending changes could have occurred through referendum or when states earmark dollars to education from sources like gaming and sin taxes (see also class action payouts)—all absent a specific education mandate from court or legislature.

In sum, SFRs are generally intended to benefit low-income districts, but this did not come to pass in fourteen states which enacted specific reforms. What’s more, some states appear ironically to have made more progress on the progressive goals of SFRs by not adopting them. It’s hard to nail down why. But this much we know: School funding formulas are complex, labyrinthine, and sometimes capricious. Student migration, economic development independent of schools, and widespread recession can all serve to undermine even the best efforts of policymakers to improve education by funding reforms. And unfortunately, with the financial fallout of Covid-19 staring at us in the face, figuring out how to fund schools is about to get even more complicated and dire.

SOURCE: Kenneth A. Shores, Christopher A. Candelaria, and Sarah E. Kabourek, “Spending More on the Poor? A Comprehensive Summary of State-Specific Responses to Finance Reforms from 1990-2014,” retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University (May 2020).

With Covid-19 cases on the rise and state budgets in crisis, federal lawmakers seem poised to pass another round of stimulus. It appears that K–12 education will receive a decent portion of the emergency aid, likely exceeding the $13.5 billion-plus provided to U.S. schools in the last package. A recent Washington Post article reports that federal lawmakers are mulling the possibility of tying K–12 funding to school reopenings—perhaps unsurprising given the president’s recent comments urging schools to reopen for in-person learning this fall.

No one can be sure whether the feds will come through with additional funds (and if so when), or whether they’d condition funding on reopening. But even if Congress doesn’t require it, state policymakers should—provided it can be done within federal rules—work to ensure that any forthcoming federal relief be used to help schools safely reopen. Here are three reasons why.

1. It’ll cost more to safely operate brick-and-mortar schools. The stringent health and safety measures that schools will need to implement are going to impose new costs. A National Science Academies report, for example, estimates $1.8 million in costs to a typical 3,200 student district. Among the expenses are hand sanitizer, masks and protective equipment, and additional bus routes. Schools may also need to purchase thermometers or scanners for temperature checks. It’s true that remote learning also poses some unique costs, most notably related to technology, but those expenses are much lower than the costs of safely operating facilities during a health crisis.

2. Reopening schools is critical to meeting student needs. A multitude of voices, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, have noted the serious harms to students, especially those with significant needs, when schools are shut. But absent prodding from state officials or parents, there’s little reason for schools to reopen this year. Some districts will receive the same funding regardless of their decision, and many face pressure from teachers unions to keep schools closed. Targeting supplemental aid to reopening could ensure that schools meet health guidelines, helping to reassure parents and teachers that it’s safe to go back.

3. Teachers and staff deserve additional pay for working onsite. Being married to a healthcare provider, I can appreciate the concerns that school employees have about going back to work. Even with safety measures in place, they’ll face greater risks of contracting the virus or spreading it to loved ones than teachers who work remotely. They’ll also have to carry out their responsibilities in an altered environment, wearing protective equipment and helping students not only learn English and math, but also how to be extra diligent about hygiene. Extra dollars would provide an opportunity to reward teachers who are going above and beyond the call of duty.

As is often the case with funding, several details about distributing funds to support reopenings would need to be ironed out. First, the distribution model would need to ensure that funds actually reach the schools that are open—a concern, for example, in districts that reopen their elementary schools but keep their high schools shut. Second, states may need a process that verifies schools are actually open. Third, the model should take into account student needs, so that high-poverty schools that reopen receive more supplemental aid than wealthier ones.

Reopening schools safely should be a national and state priority. Students, foremost, need schools to be in operation so that they can continue making progress after significant time out of the classroom. Many parents are also counting on schools to reopen so that they can get back to work. Targeting relief funds towards reopening schools would be another step in supporting students and families during these difficult times.