- On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a case about a North Carolina charter school’s dress code. In doing so, SCOTUS also declined the opportunity to declare charter schools public—or not. —The 74

- A new report offers practical recommendations to support the hard work of implementing K-12 Education Savings Accounts. —The 74

- In Spain, former Secretary of State for Education Montse Gomendio faced policy challenges that resonate with ours in the United States. —Education Week

- An American writer reflects on his daughters’ enrollment in a Chinese school. — The New Yorker

- Quite the mixed bag of stuff today, including two staple topics of Gadfly Bites. First up: Drama in Youngstown. Community activist Jimma McWilson has been hammering on the inadequacies of Youngstown City Schools for many many years. So it seemed par for the course at first to see him on TV news this week decrying poor performance and calling on leaders to do better on behalf of students. Again. (WKBN-TV, Youngstown, 6/27/23) However, having been paying attention to this topic for many years myself, it seemed to me that McWilson may have been grinding some new and specific axe here, especially as he called out the mayor’s office and city council along with school district leaders. Sure enough, it seems I missed a dust up from last week where McWilson’s community support organization was denied funding by the city—from a federal Covid-relief grant—for a tutoring program to specifically help boost the academic achievement of what he terms “under-educated former students” of Youngstown City Schools “who are now in the city without the educational tools to be economically viable and qualified to acquire the knowledge, skills, and abilities to legally engage in meaningful work to sustain themselves and their families.” The funding was withheld retroactively, it seems, following approval of the program back in December. More to come on all of this, I reckon. (WKBN-TV, Youngstown, 6/20/23)

- We’ve also been following this Commercial Drivers License (CDL) training facility boondoggle in Toledo City Schools for a good while now here in the Bites. The purported benefits for the district still ring false for me—particularly the projected budget savings and the “solving bus driver shortages” benefits—even as ground is (finally) broken after a good long bureaucratic and political slog. Should this all actually work as predicted and a number of students do indeed graduate from high school already having earned their CDL, won’t they all just become long haul truckers and start making bank the day after graduation, rather than languishing in a five-hours-a-day-with-a-hole-in-the-middle district bus driver job the following fall? Not to mention the fact that no one else besides me seems to be reckoning on the transformational transportation changes hopefully coming to every school in Ohio thanks to the state budget. It’s like they don’t even pay attention to the important stuff. (Toledo Blade, 6/27/23)

- Finally today, Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb appointed two new members and reappointed three existing members of the board of Cleveland Metropolitan School District. They and their continuing cohorts on the board will get to work starting next week. (Signal Cleveland, 6/27/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Editor’s note: This is an edition of “Advance,” a newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on the Fordham Institute website and the newsletter’s Substack.

Last week, the U.S. Department of Education released the latest batch of alarming national test results for America’s students—this time, long-term-trend data for thirteen-year-olds in reading and math. This builds on three other releases since 2022: long-term-trend data for nine-year-olds, scores for fourth and eighth graders, and civics and U.S. History results for eighth graders.

The nation is, at this point, well aware of the problem: Students everywhere suffered learning losses during the pandemic, especially those from marginalized backgrounds. As I’ve written multiple times, this is true for advanced learners, too—the subset of students who have reached, or have the potential to reach, the high end of the achievement spectrum—who are also the students on which this newsletter focuses. The latest batch of scores for thirteen-year-olds supports all of this.

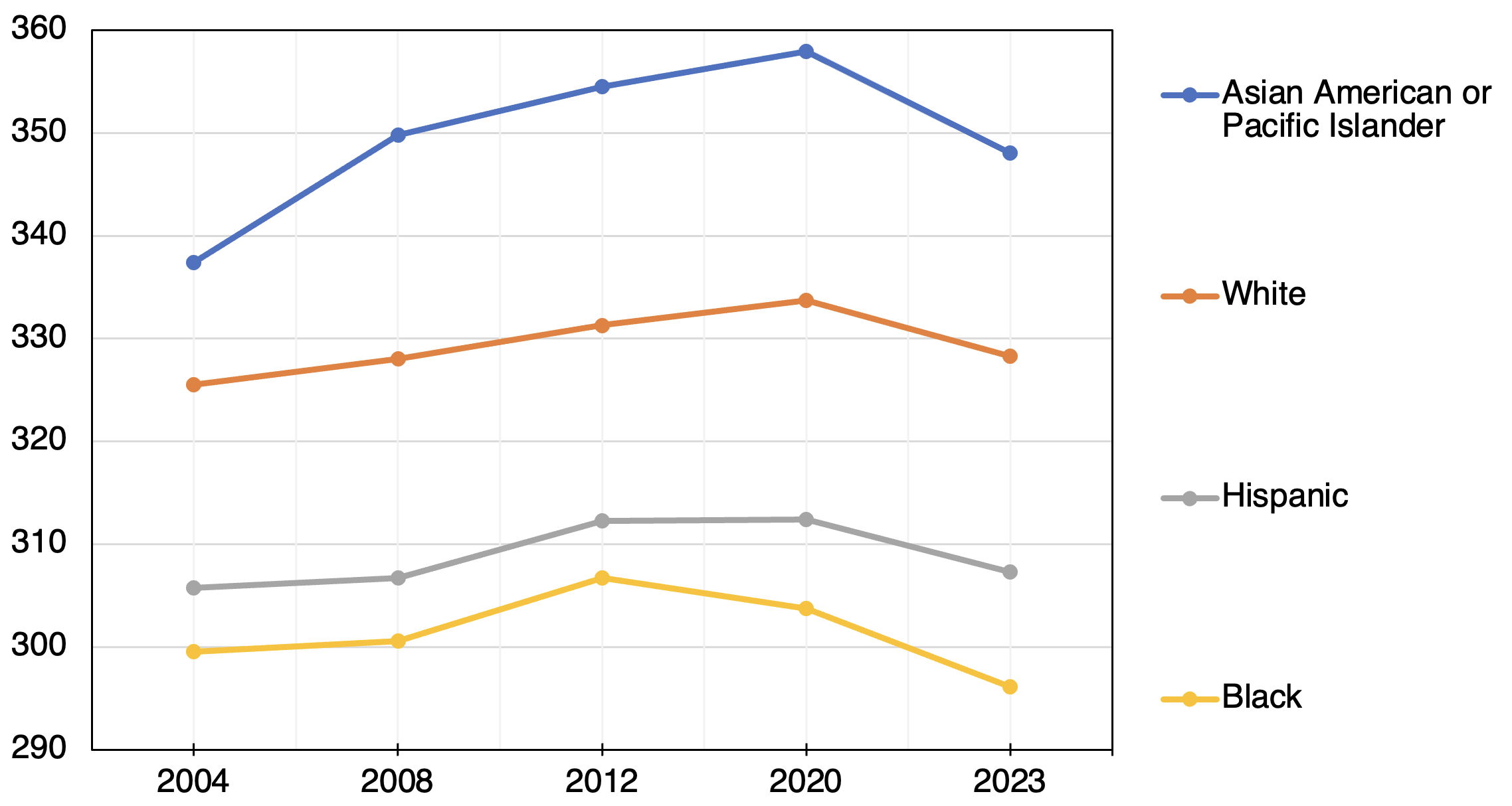

Consider, for example, the results for math—where “proficiency in eighth grade is one of the most significant predictors of success in high school,” according to a Wall Street Journal report last year. Figure 1 shows 90th percentile marks by race and ethnicity.

Figure 1. NAEP long-term trend mathematics assessment, 90th percentile scores, by race and ethnicity, 2004–23

At least three takeaways are noteworthy. First, of course, are the huge gaps in performance between groups, with the 90th percentile scores for Black and Hispanic students being far below those for White and Asian or Pacific Islander (AAPI) students. Second, those gaps have grown since 2004, with the Black-AAPI difference going from 37 points to 52 points, for example, and the Black-White gap widening from 26 to 32 points. Third, top scores dropped significantly for all the groups after the pandemic, with those for AAPI, White, and Hispanic students falling back to where they were approximately fifteen years ago—and those for Black students plummeting well below where they were twenty years ago.

But again, none of this is new or surprising. It’s just tragic and worrisome. The challenge now is doing something about it—finding ways to reverse these losses and get students closer to where they would’ve been had Covid and related mitigation policies not decimated learning.

For advanced learners, an excellent place for districts, charter networks, and states to start is a report released this month by The National Working Group on Advanced Education—a collection of twenty researchers, practitioners, and advocates (including myself), who are diverse in terms of ideology, race, gender, and geography. We met four times over the past year, and the report is the product of that work. It comprises thirty-six recommendations for how K–12 leaders can build a continuum of advanced learning opportunities, customized to every student’s needs and abilities—especially for those from marginalized backgrounds.

Leaders would be wise to follow all thirty-six recommendations, but those that fall into two categories are particularly relevant in the context of pandemic learning loss: identification and equitable achievement grouping.

As we write in the report, schools shouldn’t think of identifying advanced learners as a “yes or no,” one-time event. The goal is to keep seeking—and finding—all students who could benefit from advanced learning, whatever the subject and whatever their grade level, all the way up to dual-enrollment in a university. This is especially true now that scores for high achievers are lower than they were before the pandemic. Schools should therefore adopt a bias toward inclusion.

Specifically, districts and charter networks should do the following (also from the report):

- Adopt universal screening to identify students with potential for high achievement. Such screening involves reviewing assessment data and/or grades for all students to identify those who might benefit from advanced learning opportunities. This has strong empirical support and leads to positive results in districts that have used it. It helps identify more students overall, and it’s especially beneficial for the students most often overlooked for advanced learning opportunities.

- Use data from universally available assessments. Multiple tests or data points are better than one because some students will shine on one assessment and not another. For example, tests that measure general ability and don’t require academic knowledge will help identify students who have the potential to perform at advanced levels of achievement but don’t yet have strong content knowledge. Nonverbal assessments can help identify students whose learning hasn’t caught up with their high potential due to language or cultural barriers.

If diagnostic or interim assessments are used universally in the early grades (K–2), districts and networks should use them as initial screeners, but at the latest they should start with third-grade statewide reading and math assessments (officials should be sure to age adjust the results so as not to miss students with late birthdays). - Use assessment data to identify additional students for advanced education services in every grade, instead of relying on a single age-based screening point that would overlook late bloomers and/or exacerbate racial or socioeconomic disparities.

- Use local (i.e., school-based) norms, especially when students are young. This means identifying and serving high-potential students in every school (for example, students whose achievement levels are in the top 10 percent in each school). As students move into high school, it may be appropriate to reference state or national norms when admitting students to advanced programs so that students are better prepared to compete in higher education and beyond. Thankfully, research shows that providing access to advanced education in elementary school can help to close equity gaps and broaden participation in advanced coursework in later grades.

Once students are identified, one the best and most popular ways to develop their potential is through flexible achievement grouping in the same or separate classrooms. Numerous high-quality studies have also found that this is a net positive for advanced students and isn’t detrimental to their peers. One study that looked at a century of research, for example, found that three models boosted outcomes: within-class grouping, cross-grade subject grouping, and special grouping for the gifted. Moreover, there seemed to be little downside for medium- and low-achieving students, and often upside.

Specifically, as we note in the report, districts and charter networks should do the following:

- Frequently and equitably evaluate all students with the purpose of moving them into appropriate achievement groups. This is not “one-and-done” tracking. Putting students in buckets that never change is ineffective, inequitable, and counter to what we know about development. Rather, schools should use data from multiple measures—such as test scores and class performance—to continually assess and move students, regularly regrouping them with multiple entry points (“on-ramps”). District and school leaders should be prepared to provide teachers with support where necessary to achieve this.

- Ensure that teachers alter the complexity and pace of the curriculum, as well as methods of teaching, when using achievement groups. Grouping is only as equitable and effective as the differentiated and culturally responsive instruction that is aligned to the needs of a given group.

- Err on the side of inclusion, so that as many students can benefit as possible. The question should be whether a student has a need or would benefit from a particular service. When this isn’t clear, schools should err on the side of giving students access to a more advanced group with intentional support. All of this avoids the problem of artificial and arbitrary scarcity.

The current state of American education is bad, and advanced learners are no exception. Policymakers and school leaders will be tempted to ignore losses at the high end, but they’d be doing so at the country’s peril. We need advanced learners, particularly students from racially underrepresented or low-income backgrounds, to be highly educated to ensure the nation’s long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation. Making these programs accessible also strengthens our society and democracy. These students and their learning therefore need to be part of the recovery effort. The recommendations listed here—and in the aforementioned report—are an effective guide.

—

QUOTE OF NOTE

“A math academy for young Black boys this summer aims to not only help the young men prepare for advanced math classes but close the widening achievement gap between the races in local schools. M-Cubed, which stands for ‘Math, Men, and Mission,’ is dedicated to help middle school students from Charlottesville and Albemarle County achieve higher math class placements once they reach high school.”

—Faith Redd, The Daily Progress, June 21, 2023

—

RESEARCH REVIEW

“Gifted and On the Move: The Impact of Losing the Gifted Label for Military Connected Students,” by Robyn Hilt, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, OnlineFirst, June 2, 2023

“Society is becoming increasingly mobile, which impacts all facets of the educational experience, including gifted education. Military students attend several different schools in their educational careers, and inconsistent criteria and identification practices among states and school districts result in a fluid gifted label for many of these students. While some aspects of school mobility are highlighted in existing research, limited attention has been paid to school mobility within gifted education. This research works to address this gap by exploring the impact of losing the gifted label on children of military members, whose relocations frequently require mobility across state and district boundaries, utilizing a unique framework, Foucault’s technologies of self. Research findings explore student perspectives on the impact of their own effort or hard work on their ability to retain the gifted label and serve as a launching point from which to explore the issue of school mobility in gifted education.”

“Development of an Online, Culturally Responsive, Accelerated Language Arts Curriculum for Middle School Students,” by Jennifer H. Robins, Laila Y. Sanguras, and Ashley Y. Carpenter, Gifted Child Today, Volume 46, Issue 3, June 2023

“In this article, we focus on two components of the Online Curriculum Consortium for Accelerating Middle School (OCCAMS) project: the curriculum frameworks and the curriculum development process. The frameworks include the Integrated Curriculum Model (advanced content, unit themes, and process/product), culturally responsive curriculum, and talent development. In our discussion of the curriculum frameworks, we share how two accelerated, online courses centered on themes that motivate and engage diverse learners: identity, heroism, conviction, and sacrifice. In addition, we highlight how the exploration of these themes through texts written by diverse authors and featuring diverse characters allows students to go on an even deeper journey into self-discovery. The second focus of this article is on the curriculum development process. We illustrate the iterative nature of the development of the curriculum, including descriptions of the site visits and use of teacher and student feedback in each stage of revisions.”

“Educational Technology: Barrier or Bridge to Equitable Access to Advanced Learning Opportunities?” by Sarah Bright and Eric Calvert Gifted Child Today, Volume 46, Issue 3, June 2023

“Using a critical technology theoretical framework that examines the impact of technology on people at the individual, educational, and global levels and addresses questions around appropriate use, accessibility, and impact, [Project OCCAMS] outcomes are explored through an interpretive focus on equity, including impacts on student achievement as well as students’ subjective experiences in the program. Potential implications for broader efforts in the field of gifted education to reduce disproportionality in gifted identification and close opportunity and excellence gaps beyond gifted identification reforms are also explored.”

—

WRITING WORTH READING

“[Lamar Institute of Technology, Beaumont, Texas,] expanding its presence through dual credit partnerships,” Beaumont Enterprise, Olivia Malick, June 25, 2023

“Progressive backlash? A coalition pressing for more selectivity in schools notches key wins in NYC education council elections,” New York Daily News, Cayla Bamberger, June 24, 2023

“Summer math academy aimed at preparing Black students, closing achievement gap,” The Daily Progress, Faith Redd, June 21, 2023

“Darien [Connecticut] DEI report finds literacy disparities and lack of diversity in gifted program, special education,” The Darien Times, Mollie Hersh, June 20, 2023

“College-level exam results among Long Island high schoolers show improvement,” Newsday, John Hildebrand, June 19, 2023

“What do gifted children need? Future Scientists Center offers answers,” The Jerusalem Press, June 19, 2023

“19-year-old UC Davis grad one of youngest people in the world to earn Ph.D.” KCRA, Hilda Flores, June 19, 2023

“World science scholars hosts science festival for gifted students from 6 continents,” World Science Scholars, June 15, 2023

“12-year-old graduated from college with a 4.0 GPA—here’s why her parents are sending her to high school,” CNBC, Rebecca Picciotto, June 15, 2023

“14-year-old Pleasanton whiz graduates Santa Clara University, gets job at SpaceX,” KTVU, June 12, 2023

The process of creating a new state budget is quickly drawing to a close, with key lawmakers set to hammer out the final legislation in conference committee. Those negotiations are ongoing, with the budget for FYs 2024–25 likely to pass by Friday.

As usual, this new budget bill is the vehicle for significant policymaking in the realm of K–12 education. From the unveiling of Governor DeWine’s spending plan and the subsequent discussions in the House and Senate, one thing is clear: Primary and secondary education is a major priority for Buckeye State leaders. Schools across the state, both public and private, are set to receive significant funding increases in the coming biennium. Along with this extra money will come numerous policy reforms that seek to improve the quality of education Ohio students receive, most notably literacy initiatives that would require schools to align instructional practices to the science of reading.

Yet several significant issues remain unsettled as the House and Senate bills head to conference committee. Let’s take a look at five of them. (We discuss a couple important charter school issues, as well as student transportation, in separate pieces.)

Third grade retention

Just over a decade ago, Ohio lawmakers enacted the Third Grade Reading Guarantee, a package of early literacy reforms that aim to ensure that all children have the foundational reading skills needed to succeed in the upper grades. One of its cornerstones is a requirement that schools retain students who are still struggling to read fluently by the end of third grade. Rigorous research finds that Ohio’s retention policy significantly boosts the achievement of retained pupils. But under political pressure from the education establishment, House lawmakers chose to ignore the benefits for students and voted to ditch the policy in their budget plan and in separate legislation. The Senate, however, disagreed and maintained this component of the Guarantee in its budget. Retention is bound to come up in conference committee, and our view at Fordham—along with other reform groups—is that Ohio must preserve the requirement. Without it, there will no longer be any “guarantee” that struggling students receive the extra time and supports needed to become fluent readers.

School governance reform

One of the Senate’s priorities this year was to pass a school governance overhaul. Leaders incorporated their original proposal, which previously passed via standalone legislation, into their version of the budget. It consists of several significant changes that include refocusing the Ohio Department of Education as the Department of Education and Workforce (DEW), requiring DEW to be led by a director appointed by the governor (instead of being a State Board of Education hire), and transferring most of the responsibilities of the state board to DEW. The overhaul appears to be on track for passage, as two of the “big three” at the negotiating table—the Senate and the governor—have made clear their desire for governance change. The House is a little more of a mystery, but based on similar revamping attempts in the past, there seems to be support in that chamber as well. Here at Fordham, we’ve supported these changes and argued that they will create a more accountable state education agency, strengthen educational leadership in Ohio, and more closely connect education and employment efforts, all while preserving reasonable checks and balances.

School funding formula

The hottest topic of the previous budget cycle in 2021 was the state’s school funding formula, with legislators ultimately green-lighting the much-discussed “Cupp-Patterson” model for use in FYs 2022–23. Its formula prescribes much higher state expenditures on K–12 education—so large, in fact, that the spending increases had to be phased-in to be affordable—and one of the questions going into this cycle was whether the new model would stick. Likely reflecting flush state coffers, state lawmakers this year are poised to keep this formula intact. House lawmakers proposed to continue phasing in the funding increases, as well as updating the “inputs” (e.g., teacher salary data) in the “base cost” model. Both of those proposals help maintain the formula, but at a $1 billion-plus expense to the state. The Senate largely stuck with the House plan, but added some tweaks that improve the functioning of the formula and rein in some of the costs. Most notably, the chamber removed an unnecessary component known as supplemental targeted assistance, as well as two guarantees based on district funding levels in FY 2020 and 2021 (though it also added a new one based on FY 2023). The Senate also made a tweak to the state share computations by removing one of the two income measures of district wealth. This probably reduces some of the formula costs and creates a more straightforward calculation of local capacity.[1]

All this means that overall K–12 education spending is bound to go up as a result of this year’s state budget. By how much—and whether the Senate modifications to the formula will hold—are the questions to keep watch on in the final budget.

Private school scholarships

At this point, there is little doubt that there will be a significant expansion of EdChoice eligibility. The question now is whether lawmakers will go the universal-eligibility route, per the Senate plan, or restrict access above a certain income level, as the governor and House proposed (400 and 450 percent of the federal poverty level, respectively). All three options ensure that more Ohio families will have access to private school education, and that is to be celebrated.

Beyond questions of eligibility, lawmakers must still consider the following: First, they should remove a provision added by the Senate that reverses a current requirement for private schools to accept EdChoice scholarship amounts as full tuition for low-income families (incomes at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or below an annual income of $60,000 for a family of four). Eliminating this policy would allow private schools to charge low-income families amounts above the voucher amount, which could place valuable options for them out of their financial reach again (for a closer look at this topic, see here).

Second, because many parents will have more educational options at their fingertips, they will need more complete information about private school quality. To that end, we continue to recommend that a student growth measure be added that shines a light on the academic progress students make year-to-year in private schools. The state already reports basic point-in-time proficiency data, as private schools are required to administer standardized exams to scholarship students. Publishing growth results alongside the existing test data would provide a more holistic picture of quality, and assist parents in making decisions on behalf of their children.

Interventions for struggling students

The Senate put forward new provisions that require schools to take steps to improve the achievement of students who are significantly behind. Specifically, schools would be required to provide, either directly or through a contracted vendor, interventions to any student scoring at the lowest achievement level (“limited”) on state exams in math, science, or English language arts. The bill isn’t prescriptive on what those interventions must be; tutoring, extended learning time, or “any other academically centered support service” can all serve the purpose. That flexibility makes sense, given the range of needs low-achieving students may have. The proposal also includes some important reporting and monitoring requirements. Schools must report to the state education agency about the progress such students are making (e.g., through diagnostic assessments), and the agency is supposed to monitor their progress. The bill also requires the agency to survey schools to determine if indeed they are providing intervention services, and submit a report to lawmakers detailing the results.

These are all promising measures that legislators should keep in place. Especially in the wake of pandemic-related learning loss, state leaders have an obligation to ensure that students who are struggling get the help they need. Requiring schools to provide intervention supports and report what they’re doing is a critical step in that direction.

***

It’s been a busy budget season filled with debates over school choice, early literacy, and a wide variety of important education-related policies. The finish line is in sight, but there are still a few more key decisions to be made. If lawmakers can keep the focus on kids and families while deciding on the issues outlined above, Ohioans can look forward to a brighter future for Buckeye students.

[1] Specifically, the Senate removes the income measure based on the median income of districts’ residents multiplied by the number of tax returns and divided by district enrollment. The other income measure—total federal gross adjusted income of district residents per pupil—is retained, as is the measure of property wealth per-pupil.

One purpose of charter schools is to serve as laboratories of innovation for public education—a deliberate effort to do things differently than the long-entrenched traditional district model. That includes serving students who are at high risk of dropping out of school—or indeed have already done so—by educating them in separate schools or programs designed to address their needs. A new issue brief from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools provides a detailed overview of this approach, which the authors call “alternative education campuses” (AECs).

Different states use their own terms—such as transfer school, second chance, dropout prevention and recovery, or options school—to denote a building or program intended to serve students who have had difficulty progressing to completion in a typical education environment. Among other constituents, AECs are commonly employed to serve students who are pregnant or parenting, with criminal records, who are overage and lacking credits, and who have experienced chronic homelessness. AEC placements are meant to help students overcome these roadblocks while also helping them move forward to achieve their academic goals. Often in AECs, the goals themselves vary based on individuals’ experiences and current needs.

The issue brief focuses on stand-alone AECs in the thirty-four states (and the District of Columbia) that had charter school laws on the books during the 2021–22 school year. It does not include district, charter, or state-run programs held within larger, non-AEC, general education schools. In the 2021–22 school year, 2,756 AEC campuses operated in these states, and 555 (20 percent) were charter schools. As of fall 2021, a total of 336,393 students were enrolled in these AECs, with 141,669 (42 percent) of them in charter AECs. As charter schools serve just 7.2 percent of all public school students nationally, the high percentage of charter AEC schools and students is striking.

Looking specifically at charter AEC students, 95 percent were in high school grades, though students as young as fourth grade were included in the analysis. Approximately half of the students were female, 74 percent were students of color—including 47 percent who identified as Hispanic—68 percent were from low-income households, 16 percent were students with disabilities, and 10 percent were English Learners.

It’s difficult to tell how well charter AECs serve these students, as accountability measures run the gamut from traditional high school test scores and graduation rates to less conventional GED and career certification completion. Different states, different school types, different student compositions, and different ages result in a maze of measures that are difficult to directly compare. But the analysts did an admirable job untangling them.

To wit: They were only able to gather consistent cohort graduation data for AECs in ten states which reported four-, five-, and six-year rates. This ends up being a small subset of the total for both charter and district AECs, but the data indicate that students who remain enrolled in AECs for a longer time are more likely to graduate (though charter AECs slightly lag their district counterparts for each cohort). Similarly, in states where data were available and direct comparisons could accurately be made, the average state test score proficiency rates among charter AECs for the 2020–21 school year were 24 percent for English language arts and 14 percent for math. These (very low) rates are slightly better than those of district AECs.

AECs often have very different goals for the students they serve, however, including credentialing, job training, and catching up with high school course credits previously missed. Improving state test scores, analysts suggest, is often a less-pressing concern for AEC leaders and students. While the issue brief does not recommend eliminating such traditional measures from AEC accountability structures, it does call for a wider and more diverse set of metrics, including measures based on the goals of any given AEC. That is, if students earning high-demand industry credentials is a central part of the AEC mission, then which credentials and how many their students earn should be as important—or maybe even more important—than test scores or high school diploma attainment.

In the end, the recommendations are a mix of the flexibility described above and some across-the-board standardization in terms of both identification of AECs and defining accountability structures. The authors point to the work of the National Charter Schools Institute’s Advancing Great Authorizing and Modeling Excellence (A-GAME) initiative, in which the Fordham Foundation participates. A-GAME focuses specifically on charter authorizers, and its AEC-related recommendations include having a clear and standardized definition of which schools are identified as AECs, as well as making sure that authorizers partner with AECs to develop evaluation goals. At the same time, those evaluation goals should include as many non-traditional measures and assessments as are possible and relevant (including universals like school climate and student engagement), focus on both growth and achievement when using with traditional test score data, and include school site reviews as a way to observe school quality.

The brief describes a unique prescription for the most specialized of schools, and one its authors feel that charters are far more adept to fill than districts.

SOURCE: Issue Brief, “Going the Extra Mile: An overview of charter school alternative education campuses,” National Alliance for Public Charter Schools (June 2023).

- Both of these summer academics-and-fun combined camp programs sound great to me. This one in Girard is probably a bit more traditional… (Tribune Chronicle, 6/23/23) …while this one in Akron is at least as innovative as Shark Tank is. Some really creative and entrepreneurial young people up there, it seems. The only problem I see with both of them? They are already over and whatever benefits kids will get from them have already ceased accruing. Doesn’t anyone running schools realize that summer break is really really long? And is a huge opportunity for some buttoned-down learning? Not sure why I’m even asking—clearly no one is around to hear me. (Cleveland.com, 6/23/23)

- Looking ahead to next school year, Dayton City Schools is, for some reason, talking about restarting their “high school kids take public transit” plan that a) is entirely optional for them to even offer, b) has never seemed to work especially well for actually getting kids to school, and c) was the source of a huge and public row between district and RTA board and staff last spring. I feel like RTA was maybe a bit unfair to the kids at the time, but I sure don’t recall the impasse getting settled in the months since then. No idea why the elected school board and their staff think they can bridge the gap between now and August. Not to mention the fact that no portion of the district’s transpo plan for next year seems set in stone at all yet anyway. Perhaps they are waiting to see if the sweeping changes to student transportation proposed in the state budget come to fruition. Yeah. That’s probably it. (Dayton Daily News, 6/24/23)

- Here’s some far better news for next school year: Three more Catholic high schools in Columbus—Bishop Hartley, Bishop Ready, and St. Charles Preparatory School—will begin accepting the Jon Peterson Special Needs Scholarship. How very awesome indeed! This is a lengthy piece and there’s a lot to learn from it, including the numbers of students on IEPs and scholarships throughout the diocese, and some really interesting details about the types of services being provided. There’s even a great interview with a family who has already benefitted from the scholarship and will now be able to continue it into high school. Seems like even more students with IEPs will be served in the future. A fantastic story! (Catholic Times Columbus, 6/26/23)

- We did not note it at the time because it seemed like a normal career move, but Columbus City Schools’ internal auditor announced her resignation back in November. Fast-forward to today and we are learning that there was way more to her decision than simply “moving on to the next adventure”. Seems like some folks in public education land really don’t like surveys. (Columbus Dispatch, 6/26/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

You might think the latest headlines proclaiming grave learning losses among U.S. thirteen-year-olds over the past three years might trigger alarm, outrage and the resolve to do something about it. But you’d be wrong, for the biggest challenge to American education today isn’t learning loss or low achievement or widening gaps. It’s resistance to taking forceful action to rectify the situation.

For a vivid, scary, on-the-ground example, see the extended account by ProPublica’s Alec MacGillis of Richmond, Virginia’s, refusal to institute the year-round school calendar that was proposed by Superintendent Jason Kamras as a way to remediate that urban district’s woeful losses and set it on a path to stronger achievement.

The problem was acute. MacGillis reports that “Research released by Harvard and Stanford last fall found that Richmond’s fourth through eighth graders had lost two full years of ground in math and nearly a year and a half in reading.” At least as worrying to local educators was returning students’ “difficulty with basic interactions.” As one principal noted to MacGillis, “Socialization with each other was huge. How to be around each other—those are building blocks for ages six to ten. There was a whole retraining—what does it look like when you and another student disagree? They had missed that, not being in the building.”

Yes, such problems are nationwide—on the student-socialization and mental-health fronts, as well as on the achievement front, with the latter including not just overall setbacks, but also widening gaps as the neediest or lowest-achieving pupils suffered the greatest losses.

Though NAEP’s “long term” assessments look a tad antiquated, the version that test-takers took last fall was the same one that their counterparts took three years earlier—and the drop-off during that period, in both math and reading, is horrendous, placing the average math score back where it was at the time of the Charlottesville summit and the average reading score back where it was during Bush 43’s first term. Though we didn’t really need more proof that we’ve forfeited a generation or two of (modest) gains in these core subjects—and are in the process of sacrificing a generation of young Americans—if this doesn’t serve as a wake-up call for policymakers and education leaders, what will?

Yet the complacency of most Americans regarding the performance of our K–12 system has long been noted, as have the many structural, institutional, and contractual obstacles to changing that system in ways that might actually alter performance. This dates back at least to 1983’s Nation at Risk report. One reform effort after another gets opposed, diluted, or repealed—or turns out to be sorely incomplete because, for example, it fails to address the school-and-classroom implementation changes that are also essential if it’s to succeed.

Covid-related learning losses and what (if anything) to do about them are the latest example. Despite being flush with federal “recovery” dollars, most places aren’t doing much or doing “more of the same” or using the “lite” version or making it optional. They’re proving unable or unwilling to agree to actions that would truly alter behavior.

As the MacGillis piece makes clear, we shouldn’t dismiss this failure as mere structural rigidities or lack of leadership, although those definitely play roles almost everywhere. But the Richmond example is one of visionary leadership and what appear to be workable plans to retool the school year in ways that would facilitate recovery, especially among students who would get additional learning time, while also tackling such enduring problems as “summer learning loss” and kids getting into trouble due to endless weeks of no school.

What killed the year-round plan in Richmond (save for a tiny pilot version that finally slipped through, affecting just two of the districts’ fifty-four schools and potentially one thousand out of 22,000 pupils) was a witch’s brew of complacency, timidity, resignation, incomprehension, union resistance, and school board politics, plus a soupcon of condescension or obliviousness among elites to the true circumstances of disadvantaged families.

Be clear that this wasn’t about school-board “culture wars” over gender, CRT, and library books. It was about making a big change in the district’s accustomed modus operandi—the calendar itself—to benefit woefully-far-behind pupils, most of them Black, in an overwhelmingly disadvantaged urban setting. If there’s any legitimate rationale for elected local school boards today, it’s so they can grapple with big education policy-and-practice issues such as this one.

But after a two-year struggle, community surveys, and the superintendent’s near-firing, they weren’t able to agree to anything more than a miniscule pilot in schools whose principals “volunteered” (after struggling for parental and teacher approval).

Why the “year-round” approach with additional learning days baked in for way-behind pupils? As MacGillis reports, although Kamras had been skeptical of this strategy before the pandemic, he said that “to ignore the impact of the pandemic and the fact that it’s going to have repercussions for years would be tantamount to sticking our heads in the ground.” MacGillis continues:

[Kamras] began to see year-round school in a new light. For one thing, it seemed more workable than adding hours to the school day, given how drained many teachers felt at dismissal time. And it avoided the drawbacks of a long break for struggling students. [Thomas Kane, an economist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education,] noted that traditional summer school is often insufficient, because it’s typically voluntary and plagued by low attendance rates. Although paying teachers and staff for additional weeks of work was an added expense, extending the year was logistically easier than other supplements, such as hiring a whole new corps of outside tutors. “We already have the school buildings and the teachers,” Kane said.

But the school board “wavered.” Two members—a former teacher and a “PTA mom”—were among those who said whoa:

Rizzi, the former schoolteacher, said that perhaps the district needed to help parents do more at home to teach reading. “There are some small things they could do to support their kids,” she said. “This doesn’t mean kids need to be in class forever.” Gibson, the former PTA leader, cited the opposition voiced by teachers and parents, and suggested that the district instead put the money toward improving summer school in 2022: “We owe the public to say, ‘We heard you.’”

A lot of surveyed parents apparently never understood the year-round plan—or never understood that their kids were academically behind. Some, predictably, argued that it would disrupt their vacation plans.

But MacGillis took himself to a low-income neighborhood where he posed that challenge to “several women on the next block who among them had about a dozen grandchildren in city schools. When I asked about the argument, made by some parents, that the shorter summer break would interfere with family trips, they scoffed, saying that few people in Fairfield Court [the local public-housing project] could afford to go anywhere.”

Most gag-inducing for me in his long and extremely well-reported piece about Richmond’s failure to adopt Kamras’s forward looking plan were these two bits:

I spoke with a newly elected member of the executive board of the Richmond teachers’ union, Melvin Hostman, who said that it was hard to agree to Kamras’s push for additional instructional time when there were so many other problems that needed to be addressed: lack of toilet paper, school buses arriving late, and widespread absenteeism among them. He added, “The whole thing about learning loss I found funny is that, if everyone was out of school, and everyone had learning loss, then aren’t we all equal? We all have a deficit.”

And:

I asked parents picking up their kids if they had been disappointed that the pilot hadn’t proceeded. One mother, Alanna Scott, said she hadn’t really seen the point of extending the year to make up for what children lost in the pandemic. “It’s past now,” she said. “Whatever they know, they should keep rolling with it. The kids don’t know what they missed.”

Gag or weep or both?

For better or worse, Ohio does most of its education policymaking during the biennial budget process. This year is no different. The current budget legislation is chock full of education provisions, and some of the most significant are in the realm of early literacy. Specifically, Governor DeWine has proposed revamping reading instruction in Ohio schools to align with the science of reading. His plan focuses on curriculum reform—schools would be required to use high-quality curricula and materials that have been vetted by the Ohio Department of Education (ODE)—and providing professional development for current teachers to support rigorous implementation.

For the most part, the House and Senate commendably kept this plan intact. Even better, the House went one step further and added provisions that would allow the state to exercise more significant oversight over teacher preparation programs. This oversight specifically focuses on early literacy and ensuring that programs teach prospective educators scientifically-based reading practices. The Senate maintained the House’s additions, and since they dovetail perfectly with the governor’s agenda, they are likely to be included in the final budget.

So what would these teacher-prep reforms do? Their main purpose is to establish a transparency and accountability framework that doesn’t currently exist. First, on the transparency side, the budget bill requires ODE and the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) to create metrics that will ensure every teacher preparation program is teaching “evidence-based strategies for effective literacy instruction aligned to the science of reading.” ODHE will then develop an audit process to review each institution’s alignment with these metrics. The results will be used to create summaries of the reading instruction strategies and practices being used in each program. The departments must complete and publicly release these annual summaries by March 31. The bill also requires the departments to develop a public dashboard that reports the first-time passage rates of students, by institution, on the Foundations of Reading exam, which many prospective teachers must pass to be licensed. Tracking this data is crucial, as first-time pass rates are important markers of how rigorously preparation programs are training aspiring educators (as opposed to only reporting rosy overall passing rates that count candidates who need to take exams multiple times).

These are big steps forward in transparency. But the legislation also focuses on accountability, too. After the initial audit, programs will be reviewed every four years to ensure their continuing alignment with the established metrics. Those that are found to be out of alignment and that fail to address audit findings within one year will have their approval revoked by the chancellor of ODHE. That’s a big deal, as it will help ensure that programs aren’t ignoring reading science in their training.

The draft budget also requires the departments to identify approved vendors that can provide scientifically-based professional development to any educator responsible for teaching reading, including the faculty of preparation programs.

It’s hard to overstate just how important these teacher preparation reforms are to the success of Ohio’s early literacy efforts. The governor’s initial plan wisely sought to address the knowledge and skills gaps that many current teachers have in the area of scientifically-based reading instruction. That’s a critical step in the right direction, as Ohio’s current workforce will be responsible for teaching tens of thousands of kids to read over the next few years. But supporting current teachers isn’t enough. To sustain Ohio’s literacy reforms, the state also needs to ensure that future teachers are well-trained.

Unfortunately, recent research indicates that too many of Ohio’s preparation programs (and many in other states, too) aren’t aligning their training with the science of reading. In May, Fordham published a report outlining an NCTQ analysis of how well (or, sadly, how poorly) Ohio’s teacher preparation programs incorporate reading science into their coursework. Just nine out of twenty-six elementary programs provide adequate coverage of all five components of reading science (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension). Six programs, including Kent State University’s graduate program and Miami University of Ohio’s undergraduate program, adequately cover just one component, or none at all. And more than half promote multiple approaches that are contrary to research-based methods—things like three-cueing, which encourages students to guess at words rather than actually read them and would thankfully be disallowed under the governor’s proposals.

Those are troubling findings. When considered alongside Ohio’s low reading proficiency rates, they demonstrate a clear need for the state to step up and ensure that teacher preparation programs are following the science of reading. Failing to do so would hamstring the proposed early literacy reforms in K–12 education. It would also make the millions of dollars set to be invested in the current teacher workforce a short-term investment with limited payoff, as schools would need to retrain many incoming teachers all over again.

Fortunately for Ohio’s students, state leaders seem to recognize the importance of holding teacher preparation programs accountable for teaching the science of reading. Kudos to leaders in the House, especially, for supporting the governor’s early literacy initiative and seeing the need to align higher education with K–12. Let’s hope that the final piece of legislation keeps all of these important literacy reforms intact.

As this year’s budget process races to the finish line, state lawmakers are the midst of making decisions about what stays and what goes. The current, Senate-passed version of the budget bill has dozens of provisions that would move K–12 education in the right direction. These proposals, which include improved charter school funding and early literacy initiatives, will hopefully sail through conference committee. But one provision related to charter sponsor evaluations should definitely be scrapped. It would significantly alter the way in which the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) calculates a sponsor’s academic rating. If enacted, it would unacceptably weaken accountability, especially for online charter schools.

By way of background, charter sponsors, or “authorizers,” are the gatekeepers of quality in the charter sector. They allow a charter school to open, keep checks on the school’s performance, and have the authority to close a school should it underperform. Various entities, including the Fordham Institute’s sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, serve as sponsors in Ohio.

To ensure that sponsors rigorously hold their schools accountable for results, state lawmakers created a system in the mid-2010s that evaluates sponsors. It consists of three equally-weighted components:

- Academics—based on the report card results of the schools a sponsor oversees;

- Compliance—based on a review of compliance with laws and regulations; and

- Quality practices—based on a review of sponsors’ adherence to best practices.

The academic dimension, in particular, is critical to holding sponsors accountable for authorizing quality schools. To compute the academic rating, ODE currently calculates an average that weights schools in a sponsor’s portfolio according to their enrollment. This is exactly the right approach. The weighted-student average ensures that all students matter and are accounted for in a sponsor’s portfolio. It also ensures that each school is given appropriate emphasis in the calculations. Larger schools carry more weight—as they should—than smaller ones.

Unfortunately, a provision in the Senate budget would require ODE to calculate two scores—and use the higher of the two to determine the academic rating of a sponsor. The first calculation would still be the weighted-student average, as described above. But the second would weight each school equally—a straight-up average that counts each school as if they had the same enrollment. This approach ignores the fact that some schools are larger—much larger, in some cases—than others. It’s akin to saying that Ohio should get the same number of electoral college votes as tiny Delaware.

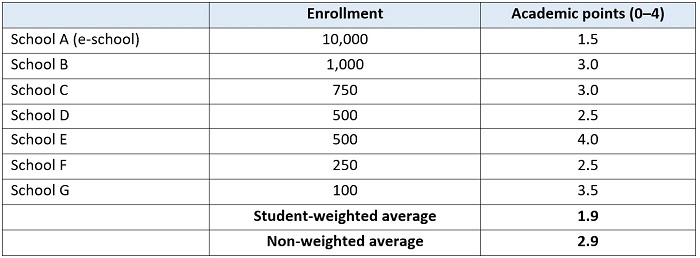

The worrisome implication of the proposal is that it could mask the poor performance of larger schools, particularly online charters that enroll thousands of students each year. By allowing the straight-up average to be applied instead of the student-weighted one, online schools—and their sponsors—would get off the hook if their academic performance is poor. Consider how the results change when using some illustrative data for a fictitious sponsor that authorizes a big e-school. (Note: The two largest online charters in Ohio enrolled 14,591 and 5,696 students in 2021–22; both posted low ratings on their report cards.)

Table 1: Illustrative calculation of a sponsor’s academic rating

Table 1 illustrates that, under current policy, the results of a large, underperforming e-school receive appropriate emphasis in the overall academic rating. The school in this example enrolls 76 percent of the students in the sponsor’s portfolio, and its results are correctly reflected in the student-weighted average. However, the non-weighted average inflates the sponsor’s score (2.9 instead of 1.9) and allows the low performance of the e-school to be papered over, even though it’s responsible for serving far more students than the other schools.

This is wrong for a couple reasons. First, students should be at the center of accountability systems. The current academic calculations do exactly that by treating students (as opposed to schools) on equal terms. If the proposal is approved, however, online students will actually count much less than their peers in other schools. Doesn’t their learning matter just as much as a student attending a brick-and-mortar charter school? Remember, in school district accountability, the state doesn’t equally weight schools of varying sizes and then compute an average for the entire district. Rather, it looks at each student enrolled in the district and counts them all equally. The same should apply to the portfolio of sponsors.

Second, accountability systems should drive improvements that benefit students. The academic component of the present evaluation system adheres to this notion. Should a sponsor authorize a large underperforming e-school, it’s incentivized to: (a) take steps to ensure that the e-school improves and (b) offset its results by authorizing high-performing brick-and-mortar charters. Those healthy incentives go away under this proposal. Sponsors’ academic ratings will go up artificially, taking the pressure off to demand improved online education while also ensuring the rest of their schools are high-performing.

Those steps backwards would threaten the tremendous progress Ohio has made in charter school accountability, and would do nothing to help solve the problem of low-performing e-schools, whose struggles have damaged the sector’s reputation in the past and continue to bog down overall charter performance. We shouldn’t go back to the dark ages of accountability, and this idea would be a regrettable reversal of sound policy.

The sponsor evaluation system remains the linchpin for overall charter sector quality. To be sure, the quality practices and compliance components of the evaluation are not perfect. There are provisions in the budget that could potentially reduce the unnecessary paperwork burdens on sponsors by requiring ODE to seek external support to review the system. However, the academic component is strong and should not be watered down. The charter sector is poised for exciting growth through long-awaited equitable funding, but legislators still need to keep the focus on providing high-quality schools for students by maintaining strong charter accountability.

Ohio budget update

The state budget bill entered conference committee this week, with Senate and House conferees working to find agreement on the points of difference between the chambers. Fordham’s Aaron Churchill notes that charter funding is likely in line for a healthy boost via increases in per-pupil funding for high-quality charters and the charter facilities allowance, as well as a brand new supplement that would move charters closer to equitable per-student funding. He is also hopeful that a further bump in the latter component could be added in the waning days of June which would move the state’s brick-and-mortar charter schools even closer to funding parity with districts.

Point-by-point response

The Columbus Dispatch recently published a guest commentary that was chock full of the misleading rhetoric and misinformation that critics typically trot out to denigrate the sector. John A. Dues, Chief Learning Officer of the United Schools Network, created a point-by-point response to that commentary and you can check it out here. You can also read Aaron’s original Dispatch editorial, pushing for improved charter funding, that led to the misinformed commentary.

Success is its own response to criticism

Former Florida governor and current Founder and Chair of ExcelinEd Jeb Bush published an op-ed in the Chicago Tribune this week, pointing out the strong student achievement data highlighted in the recent report from CREDO. “Those results on their own are remarkable,” Bush writes, “but perhaps most important for the public policy debate is data showing charter schools have disproportionately helped low-income and minority students—the students these schools are designed to help.”

Teachers say…

This week, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools released a sneak peek of the findings from their new national survey of public school teachers—district and charter—conducted in mid-May. Among the topline findings: Teachers in both sectors are more concerned about student behavior and discipline issues than they are about pay. The vast majority say they “just want to teach” and report feeling like they have gotten caught in a political crossfire over cultural issues. Interestingly, charter school teachers report significantly higher job satisfaction than their district school peers, and are far more likely to agree with the sentiment that “being a teacher is the most rewarding job in the world”. Full data are to be released later this summer.

The view from New Hampshire

On Monday, legislative conferees in New Hampshire came to agreement on House Bill 536 which would, among other provisions, add some guidelines around the process by which charter schools in the state may buy vacant property from districts. Specifically, the bill requires districts to engage in good faith talks within 60 days of receiving a charter school’s offer to buy a property. House members are scheduled to return to session June 29 to vote on this and other legislation approved by conference this week.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.