Historically, many American students from poor families have been trapped in sorely underfunded public schools. The conventional wisdom suggests that school funding remains unequal across low- and high-income schools and that equal funding equates to equitable resources for students. This brief challenges the notion that economically disadvantaged students receive less funding than other students, with implications for equalizing classroom resources and optimizing other social policies.

Executive Summary

Specifically, this brief addresses the following ideas that have become conventional wisdom in some quarters:

Conventional wisdom (CW):“Students from traditionally disadvantaged backgrounds attend poorly funded schools.”

Not anymore. School funding has risen dramatically over the last few decades, especially in schools serving more students from low-income families.

CW: “Better school funding makes a difference to students from low-income families.”

Generally true. Over the last two decades, the evidence that “money matters” to school performance has become much stronger and shows that school funding is even more important for students from poor families.

CW: “School funding remains unequal across low- and high-income schools.”

Wrong. School-finance reforms and, to a lesser extent, increases in federal education funding have eliminated the gaps between schools serving more- and less-affluent students, at least when those schools are within the same state.

CW: “Eliminating the SES gaps means racial/ethnic funding gaps disappear, too.”

Mostly true, but there are exceptions. A few states that have eliminated gaps in funding for students of different socioeconomic status (SES) still have funding gaps by race.

CW: “Equal funding means equitable resources for students.”

Not necessarily. Ensuring access to some resources, such as high-quality teachers, costs more in schools that serve more disadvantaged student populations.

CW: “Even if school funding is equal, it’s not adequate to meet students’ needs.”

“Adequacy” is an inherently subjective, unscientific concept. Consequently, what constitutes “adequate” funding will inevitably be contested and variable across communities.

The Bottom Line

For decades, many American students from poor families were trapped in sorely underfunded public schools while more affluent families had access to better-funded ones. But times have changed. School-finance reforms and, to a lesser extent, increases in federal funding have largely equalized school funding over the past few decades. Although not all fiscal gaps have been closed in every state, school funding within states is now generally progressive, meaning that students from poor families generally attend better-funded schools than students from wealthier families, and disparities in outcomes between student groups can no longer be attributed to funding gaps. In response to this shift, equity-minded school-finance reformers now advocate for “adequacy” funding, but because adequacy is a subjective concept, that goal is likely to be elusive.

Policy Implications

- Because funding is already progressive, improving the outcomes of lower-performing students requires reforms to make schools more efficient using the funds they already have and/or allocating funding even more progressively.

- Gaps in funding by race continue in a few states and should prompt continued action to provide equalized funding.

- Focusing on equalizing classroom resources, such as access to high-quality teachers, is an objective with a more commonsense rationale—likely making it more politically tenable—than providing “adequate” resources, which is more subjective.

- The effectiveness of increased education funding faces diminishing returns in some places, and other policy improvements, from better health care to offering child tax credits, may improve the lives of students overcoming disadvantages more than additional funds for schools.

––––––––––––

This brief analyzes the extent to which public K–12 schools are funded unequally and discusses continued challenges related to equitably funding schools. It evaluates six statements that have become the conventional wisdom among some in the public or policymaking community, including the following:

“Students from traditionally-disadvantaged backgrounds attend poorly-funded schools.”

“Students from traditionally-disadvantaged backgrounds attend poorly-funded schools.” Not anymore.

Not anymore.

Some of the earliest analyses of school funding disparities were conducted by the NAACP. In his history of that organization’s legal work, law scholar Mark Tushent recounts a series of school-spending analyses that the civil rights group produced in the 1920s. Back then, segregated Black schools in Georgia and Mississippi received just one-eighth and one-fifth, respectively, of what segregated White schools in the same states received. Although North Carolina was “without a doubt the best” of the Southern states, the funding ratio was merely “less than two to one,” and Black teachers had a minimum salary substantially lower than the White minimum. Schools were separate and unequal.

The period of school integration following Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the successes of the civil rights movement brought welcome changes but did not come close to ensuring that schools were appropriately funded. Schools attended by poor, Black, and Hispanic students remained poorly funded because of both family choices and misguided public policies. White and middle-class families leaving urban cores in previous decades devastated local tax bases, leaving many schools chronically underfunded. Because American schools have traditionally been funded largely through local property taxes, high-poverty districts often received paltry resources. When writer and educator Jonathan Kozol toured American schools in the 1980s, he encountered urban schools that were “overcrowded and understaffed, and lacked the basic elements of learning—including books and, all too often, classrooms for the students.” What Kozol deemed “savage inequalities” between the wealthiest and poorest communities in the 1970s and 1980s were no myth.

Yet beginning in the era when Kozol was first documenting those stark differences in school resources, civil rights activists, litigants, and voters pushed for more equitable funding for schools. In 1968, John Serrano, a Mexican-American parent of students in an east Los Angeles county school district, Baldwin Park Unified, sued the state based on the drastic differences in funding between his zoned district and the more affluent school districts in L.A. In the 1971 California Supreme Court case Serrano v. Priest, the Court ruled that California’s “funding scheme invidiously discriminates against the poor because it makes the quality of a child’s education a function of the wealth of his parents and neighbors.”

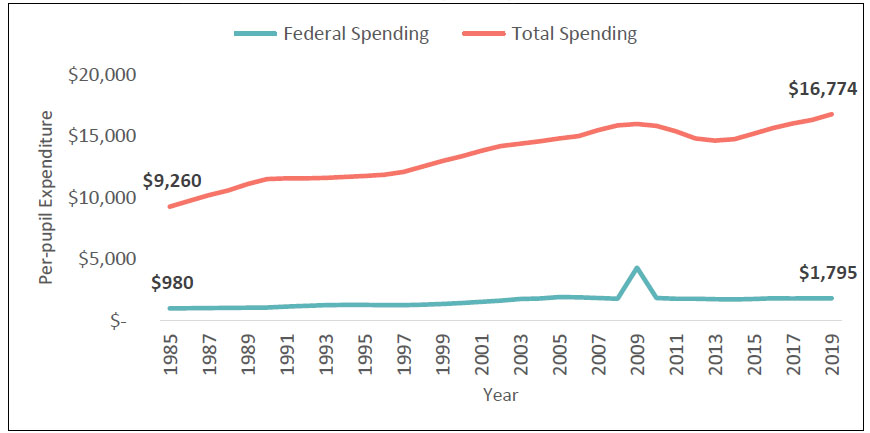

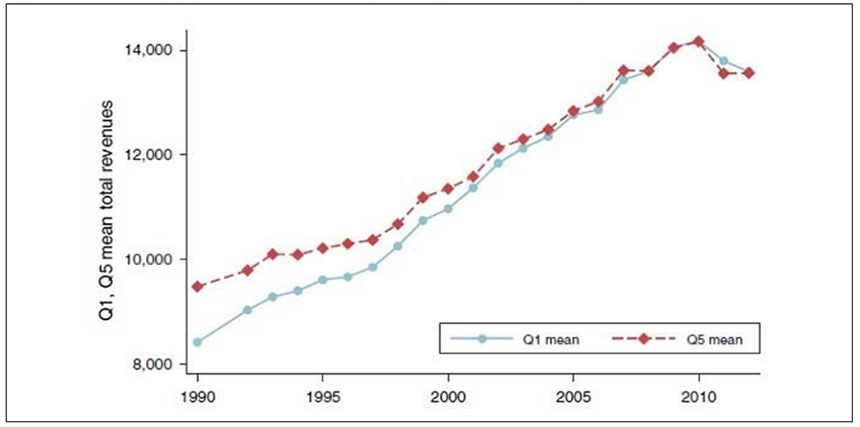

Since the Serrano decision, state supreme courts have forced school finance reforms in 26 other states, and those reforms have generally led to more spending for the schools serving the lowest-income students. Many states have also passed laws increasing funding for these schools, including as recently as 2022, when Tennessee switched to a student-based funding model that allocates additional resources to students from poorer families. Federal education funding, which is largely dedicated to schools with many students facing poverty, has also increased modestly over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Per-pupil, inflation-adjusted school spending has soared over time.

Note: Author’s calculations from Digest of Education Statistics tables 203.10, 236.55, and 401.10. All spending amounts are inflation adjusted in constant 2021 dollars.

Note: Author’s calculations from Digest of Education Statistics tables 203.10, 236.55, and 401.10. All spending amounts are inflation adjusted in constant 2021 dollars.

As shown, per-pupil school funding increased 81 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars from 1985 to 2019. And since the Covid-19 pandemic, schools have been showered with hundreds of billions in federal relief funds. Although a fiscal cliff looms when those funds expire, as of this writing students in virtually all American public schools—but especially those attending schools with many students from low-income homes—are experiencing unprecedented spending.

“Better school funding makes a difference to students from low-income families.”

“Better school funding makes a difference to students from low-income families.” Generally true.

Generally true.

For decades, going back to the landmark Coleman Report in the mid 1960s, some have questioned whether “money matters” for schools, pointing to weak correlations between school spending and student outcomes as evidence that lack of spending wasn’t the problem. Yet a raft of rigorous studies over the past two decades has made it clear that school funding does indeed make a difference to school performance.

Many of the more recent studies of school-finance reforms—Northwestern University economist Kirabo Jackson reviews 35 of them in a recent working paper—leverage the fact that they were implemented abruptly as a result of court mandates or close ballot initiatives. And the studies tell a remarkably consistent story: school spending makes a difference for all students, especially for students from low-income families. For example, one study of multiple states found no overall effect of increased spending as a result of tax increases that boosted school spending. However, that paper’s analysis of subgroups found that the increased funding led students from lower-income families to earn higher scores on end-of-year tests and to graduate at higher rates.

Of course, funding skeptics have a point when they say that education leaders should use their funds wisely and focus resources in ways that maximize results for students. Many expensive interventions, from reducing class sizes to hiring teachers with more advanced degrees, often do little to increase student learning. Yet the activists and educators who sounded the alarm about insufficient and unequal school funding weren’t wrong: properly funding schools is an important issue, and for too long the students attending those dilapidated, underfunded schools were denied opportunities by America’s longstanding and systemic inequalities.

“School funding remains unequal across low- and high-income schools.”

“School funding remains unequal across low- and high-income schools.” Wrong.

Wrong.

State-level school finance reforms and, to a lesser extent, increases in federal funding for schools have had a predictable but little-discussed effect: America’s shamefully persistent inequities in school funding are finally a thing of the past.

Unfortunately, many education advocates and scholars have generally not acknowledged this progress. Influential educationist Linda Darling-Hammond wrote as recently as 2013 that “in most states, there is at least a three-to-one ratio between per-pupil spending in the richest and poorest districts.” A 2019 article from Vox puts the conventional wisdom succinctly, arguing that because some school funding comes from local property taxes, public “schools in wealthier areas get better funding.”

Research shows such claims are wildly out-of-date. In fact, school funding is now generally progressive, meaning that students from poor families generally attend better-funded schools than students from wealthier families. Studies show that the era of savage inequalities has been over for decades.

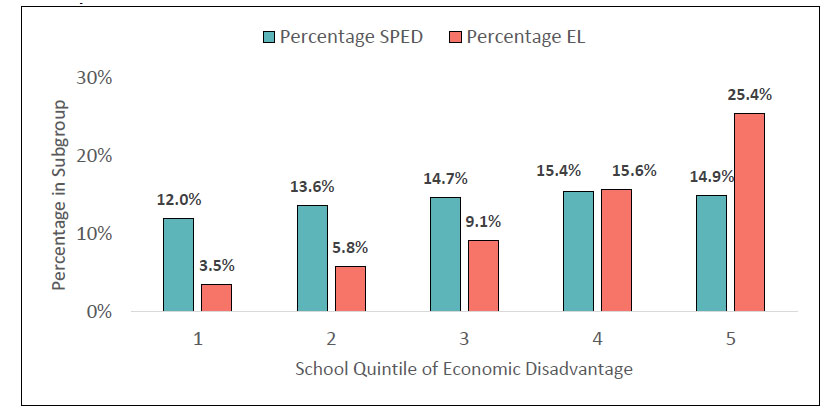

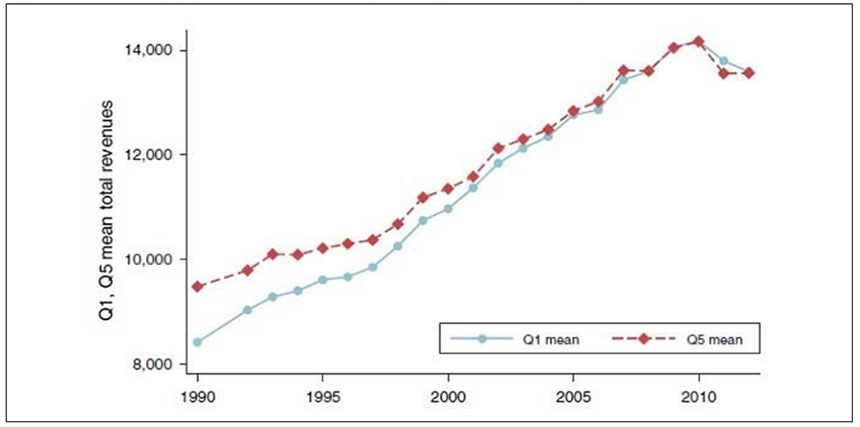

Looking at school districts with the wealthiest and poorest populations within each state, a 2018 study by a team of Berkeley economists found yawning funding gaps in 1990 (Figure 2). Yet over the span of fifteen years, these gaps completely disappeared. Funding for students in wealthier and poorer districts had, by 2005, been equalized, and the gap remained closed through 2013, when their data set ended.

Figure 2. Yawning gaps in district-level spending were closed by the mid-2000s.

Note: Income quintiles are defined within states by the mean household income in the district in 1990, and revenues are expressed in 2013 dollars. The figure has been reproduced from Lafortune et al. (2018), who also note that districts are averaged within states and weighted by district enrollment (excluding Hawaii and the District of Columbia).

Note: Income quintiles are defined within states by the mean household income in the district in 1990, and revenues are expressed in 2013 dollars. The figure has been reproduced from Lafortune et al. (2018), who also note that districts are averaged within states and weighted by district enrollment (excluding Hawaii and the District of Columbia).

Several studies by the Urban Institute have also shown funding gaps disappearing. Their 2017 study used a series of stunning data visualizations to show that progressively allocated state and federal funding now outweighs the regressive effect of local funding sources, and only three states (Illinois, Nevada, and Wyoming) continued to have slightly regressive funding at the district level. A 2017 Brookings Institution study conducted by Urban Institute’s Matt Chingos shows that progressive funding for schools goes back to at least the mid-1990s. When the Urban Institute itself used a somewhat different methodology to study school finance in 2022, they still found that funding was slightly progressive: “1 percent more funding is allocated to students from households in poverty nationwide than toward students from households not in poverty.”

School-level data on these questions have only been available at scale for a few years, but the new analyses using that more granular data find that school-level spending is even more progressive than at the district level. This is not only because federal and state funding often targets low-income students but also because district funding itself is often allocated progressively. The most comprehensive study of school-level spending is from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Delaware (hereafter, “Lee et al.”), and it shows that it is actually much more common for schools with poorer students to spend more than other schools in the same state—on average $529 more per student per year (that study uses free and reduced-price lunch qualification and census-based poverty metrics to operationalize student socioeconomic status (SES), with similar results using both measures). The only state where spending in schools serving poorer students is still markedly lower than in those serving wealthier ones is Illinois, which enacted school funding reforms in 2017, after the time period that Lee et al. analyzed. In New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Connecticut, funding for schools serving more low-income students is very slightly lower, but in the rest of the states, school funding is either equal or higher for the schools serving more low-income students.

“Eliminating the SES gaps means racial/ethnic funding gaps disappear, too.”

“Eliminating the SES gaps means racial/ethnic funding gaps disappear, too.” Mostly true, but there are exceptions.

Mostly true, but there are exceptions.

Similar to SES, the conventional wisdom is that Black and Hispanic students are more likely than White students to attend poorly funded schools. For example, a 2019 report from former fiscal advocacy group EdBuild said that students in “non-White” districts—those in which non-White students were at least 75 percent of the population—received $23 billion a year less in funding than mostly White districts received, evoking the deep institutional racism of the era in which those first NAACP studies were conducted. But that eye-popping figure excluded federal funding, which is allocated quite progressively. Since Black and Hispanic students are more likely than White students to live in poverty, those additional monies were not captured in the EdBuild data.

Studies that include federal, state, and local funding and look within states generally find equal funding for students of different racial/ethnic backgrounds, but there are some exceptions. Using somewhat different methodologies, both Lee et al. and a 2022 Urban Institute report use school-level data to show that funding for Black students is generally greater than that for White students in the same state, while funding for Hispanic students is at least as much as that for White students in the same state. Specifically, Lee et al. find that, “On average, Black and Hispanic students receive $514 and $115 more per pupil than White students, respectively.”

It is true, however, that funding gaps based on race/ethnicity are more common than those based on SES. Whereas Lee et al. find only a handful of states where total school-level funding is even slightly regressive, they identify more than twenty states where Black or Hispanic students are funded at lower levels than their White counterparts, although only a few of those differences are statistically significant. Texas is a place where the racial school funding gap remains; although that state provides equal funding for more and less affluent students according to Lee et al., each Black student is, on average, funded at about $1,000 less per year than his or her White counterpart.

Although equity advocates shouldn’t exaggerate the problem, the persistence of racial disparities should prompt action in the places where they still exist.

“Equal funding means equitable resources for students.”

“Equal funding means equitable resources for students.” Not necessarily.

Not necessarily.

Although funding gaps have mostly been eliminated, financial resources are not necessarily equivalent to classroom resources. The clearest example of this disconnect is continuing disparities in teacher quality. As Lee et al. put it, “The teacher-quality gap is not being remedied by progressivity in” spending. A number of other studies have likewise shown that it costs more to recruit and retain high-quality teachers in schools serving more disadvantaged students. Policies that reward educators who choose to teach in higher-needs environments, such as Texas’s Teacher Incentive Allotment, are meant to lessen such resource inequality but aren’t typically enough to eliminate the disparities. Lee et al. report that economically disadvantaged, Black, and Hispanic students tend to have smaller class sizes. Because such a policy tends to drive up staffing costs while offering minimal benefit to student learning, it is a good example of how different types of resource inequities can become so disconnected from overall spending patterns.

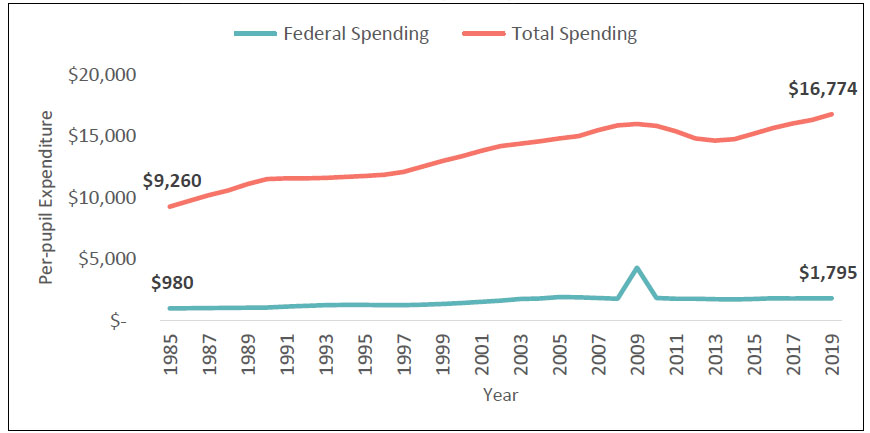

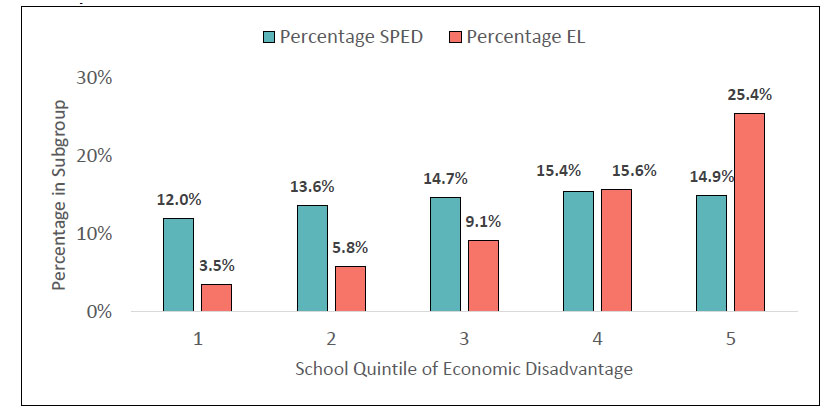

Because economic disadvantage also correlates with additional student needs (Figure 3), it makes sense to account for the share of students needing special education and English learning services, as well. Although many school-funding formulas allocate more to schools serving these student populations, the very slight progressivity in school spending suggests that schools serving less-affluent communities might often need more funds than they are currently receiving to fund such programs.

Figure 3. Higher-poverty schools have more English learners and slightly more students with special needs.

Note: Author’s calculations based on weighted averages of 59,045 schools with complete data on students with special needs (SPED), limited English proficiency (EL), and economic disadvantage in the 2021–22 EdFacts reports. Schools in three states are excluded because of lack of data (Delaware) or reporting nearly all students as economically disadvantaged, SPED, and/or EL (Illinois and Oregon).

Note: Author’s calculations based on weighted averages of 59,045 schools with complete data on students with special needs (SPED), limited English proficiency (EL), and economic disadvantage in the 2021–22 EdFacts reports. Schools in three states are excluded because of lack of data (Delaware) or reporting nearly all students as economically disadvantaged, SPED, and/or EL (Illinois and Oregon).

Other resource inequities persist, as well. Special programs, such as Advanced Placement and extracurricular activities, are less likely to exist in schools serving students coming from disadvantaged backgrounds. Although some resources, such as whether a school has a program for “gifted” students, are not correlated with the SES of schools, it’s true that offering the same kinds of resources to all student groups means that higher-needs schools often require significantly more funding than those serving more affluent populations. Thus, some state funding systems should be even more progressive than they already are.

“Even if school funding is equal, it’s not adequate to meet students’ needs.”

“Even if school funding is equal, it’s not adequate to meet students’ needs.” “Adequacy” is an inherently subjective, unscientific concept.

“Adequacy” is an inherently subjective, unscientific concept.

The equalization of school funding in the United States is a major achievement, however belated. The severe school-funding inequalities of the past made a mockery of equality of opportunity in America. Greater school funding has been shown to make a difference, especially to disadvantaged students, and it is sensible policy to fund the schools that these students attend at least as well as we fund the schools that advantaged students attend. It is also sensible for policymakers to attempt to equalize resources, such as access to high-quality teachers, meaning that progressive—or even steeply progressive—funding is likely to be necessary in many communities.

An ambitious approach, sometimes called “adequacy funding,” demands that school funding be based on what is necessary to help equalize outcomes between student groups, with some claiming that the precise amount of adequate funding can be calculated using available data. Unfortunately, equalizing outcomes does not lend itself to a technocratic solution that enables policymakers to calculate the “right” amount of funding. Thus, the “adequacy” framework contributes little to our understanding of how best to allocate education funding.

Consider a 2018 paper by Rutgers professor Bruce Baker and his coauthors, which defines adequacy as enough funding to meet the “costs associated with achieving national average student achievement outcomes” for all groups of students. Such an approach would still cost far more than is currently spent, even after large increases in education funding in recent years (see Figure 1). Even accepting all of their (arguably questionable) assumptions, Baker and his coauthors suggest that adequate funding would be in the range of $20,000 to $30,000 per high-poverty student per year, an amount that equates to the huge temporary infusions meant to help schools overcome the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic. A recent report entitled Equal Is Not Good Enough by the Education Trust cites Baker and his colleagues and likewise suggests spending two to three times more on low-income students than what is spent on more affluent students.

Yet journalist Matt Barnum has pointed out that even in some of the localities where school spending meets these stratospheric targets, such as the state of New York, students “don’t actually achieve the average outcomes that [Bruce Baker’s study] would predict.”* This underscores the importance of broader education reforms that focus not only on school funding but also on how to make schools more efficient with the resources they have.

More fundamentally, the adequacy approach puts too much of the onus on schools to solve society’s broader inequities, as if greater school funding were the only way to improve the life chances of young people. Children do not start school at the same levels, and myriad social conditions are baked into the gaps observed between groups’ average test scores, grades, and other measures of academic achievement. Expecting schools to compensate for all these discrepancies inevitably crowds out other approaches. Many other social policies—such as food stamps, housing policy, health care access, better policing, or family tax credits—have discernible effects on education outcomes. And since school funding surely has diminishing returns, increasing it alone will fall short of the goal to improve vastly the opportunities of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Equalizing school funding and resources helps underserved students and provides basic fairness within our public education system. But as economist Eric Hanushek explains, the adequacy framework “ignores the simple fact that determining the level of public spending on schools is a political decision, vested with legislatures and governors.” Beyond more limited goals, such as equalizing student access to good teachers, there is simply no technocratic answer to the question of how much extra funding higher-needs schools deserve, and it is appropriate that different communities will adopt different funding priorities.

Policy Implications

- Because funding is already progressive, improving the outcomes of lower-performing students requires reforms to make schools more efficient using the funds they already have and/or allocating funding even more progressively.

- Gaps in funding by race continue in a few states and should prompt continued action to provide equalized funding.

- Focusing on equalizing classroom resources, such as access to high-quality teachers, is an objective with a more common-sense rationale—likely making it more politically tenable—than providing “adequate” resources, which is more subjective.

- The effectiveness of increased education funding faces diminishing returns in some places, and other policy improvements, from better health care to offering child tax credits, may improve the lives of students overcoming disadvantages more than additional funds for schools.

*Errata: An earlier version of the report referenced "the few localities" versus "some localities." The latter is more accurate. We apologize for the error.

References

Abott, Carolyn, Vladimir Kogan, Stéphane Lavertu, and Zachary Peskowitz. “School District Operational Spending and Student Outcomes: Evidence from Tax Elections in Seven States.” Journal of Public Economics 183 (March 2020): 104142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104142.

Adamson, Frank, and Linda Darling-Hammond. “Funding Disparities and the Inequitable Distribution of Teachers: Evaluating Sources and Solutions.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 20 (May 21, 2012). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v20n37.2012.

Aldrich, Martha A. “Tennessee Governor Signs Public Education Funding Formula into Law.” Chalkbeat Tennessee, May 2, 2022. https://tn.chalkbeat.org/2022/5/2/23054374/tisa-bep-school-funding-law-tennessee-governor.

Baker, Bruce D., Mark Weber, Ajay Srikanth, Robert Kim, and Michael Atzbi. The Real Shame of the Nation. Washington, D.C.: Albert Shanker Institute, 2018. https://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/The%20Real%20Shame%20of%20the%20Nation.pdf.

Barnum, Matt. “As Pandemic Aid Runs Out, America Is Set to Return to a Broken School Funding System.” Chalkbeat, August 25, 2022. https://www.chalkbeat.org/2022/8/25/23318969/school-funding-inequality-child-poverty-covid-relief.

———. “The Racist Idea That Changed American Education.” Vox, February 13, 2023. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/23584874/public-school-funding-supreme-court.

Barnum, Matt, and Reema Amin. “New York Schools See a Big Disconnect between Spending and Test Scores. Why?” Chalkbeat New York, August 26, 2022. https://ny.chalkbeat.org/2022/8/26/23319844/new-york-school-spending-test-scores-disconnect.

Bastian, Jacob, and Katherine Michelmore. “The Long-Term Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Children’s Education and Employment Outcomes.” Journal of Labor Economics 36, no. 4 (October 2018): 1127–63. https://doi.org/10.1086/697477.

Beharie, Nisha, Micaela Mercado, and Mary McKay. “A Protective Association between SNAP Participation and Educational Outcomes Among Children of Economically Strained Households.” Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 12, no. 2 (2017): 181–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2016.1227754.

Biasi, Barbara. “School Finance Equalization and Intergenerational Income Mobility: Does Equal Spending Lead to Equal Opportunities?” SSRN Electronic Journal (2015). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2846490.

Blagg, Kristin, Julien Lafortune, and Tomás Monarrez. Measuring Differences in School-Level Spending for Various Student Groups. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, October 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/Measuring%20Differences%20in%20School-Level%20Spending%20for%20Various%20Student%20Groups.pdf.

Blew, Jim. “Enough Already.” Education Next, April 11, 2022. https://www.educationnext.org/enough-already-biden-asks-congress-for-tens-of-billions-education-spending.

Boyd, Donald, Hamilton Lankford, Susanna Loeb, and James Wyckoff. “Understanding Teacher Labor Markets: Implications for Educational Equity.” In School Finance and Teacher Quality: Exploring the Connections, AEFA 2003 Yearbook, edited by Margaret L. Plecki and David H. Monk, 55–84. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education, 2003. https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/understanding-teacher-labor-markets-implications-educational-equity.

Brunner, Eric, Joshua Hyman, and Andrew Ju. “School Finance Reforms, Teachers’ Unions, and the Allocation of School Resources.” EdWorkingPapers, October 2018. https://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai19-35.

Candelaria, Christopher A., and Kenneth A. Shores. “Court-Ordered Finance Reforms in the Adequacy Era: Heterogeneous Causal Effects and Sensitivity.” Education Finance and Policy 14, no. 1 (2017): 1–91. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00236.

Carter, Prudence L., Kevin Grant Welner, and Gloria Ladson-Billings, eds. Closing the Opportunity Gap: What America Must Do to Give Every Child an Even Chance. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, and Jonah Rockoff. New Evidence on the Long-Term Impacts of Tax Credits. Washington, D.C.: National Tax Association Proceedings, November 2011. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/11rpchettyfriedmanrockoff.pdf.

Chingos, Matthew M. “How Progressive Is School Funding in the United States?” Brookings, June 15, 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-progressive-is-school-funding-in-the-united-states.

Chingos, Matthew M, and Grover J Whitehurst. Class Size: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2011. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/0511_class_size_whitehurst_chingos.pdf.

Chyn, Eric. “Moved to Opportunity: The Long-Run Effects of Public Housing Demolition on Children.” The American Economic Review 108, no. 10 (October 2018): 3028–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161352.

Costrell, Robert, Eric Hanushek, and Susanna Loeb. “What Do Cost Functions Tell Us about the Cost of an Adequate Education?” Peabody Journal of Education 83, no. 2 (2008): 198–223.

Dynarski, Mark. “The Challenges of Promoting Equal Access to Quality Teachers.” Brookings, October 2, 2014. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-challenges-of-promoting-equal-access-to-quality-teachers.

Darling-Hammond, Linda. “Inequality and School Resources.” In Closing the Opportunity Gap: What America Must Do to Give Every Child an Even Chance, edited by Prudence L. Carter and Kevin Grant Welner, 77–97. Oxford University Press, 2013.

EdBuild. $23 Billion. Jersey City, NJ: EdBuild, February 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20200407000302/https:/edbuild.org/content/23-billion/full-report.pdf.

Gassman-Pines, Anna, and Laura Bellows. “Food Instability and Academic Achievement: A Quasi-Experiment Using SNAP Benefit Timing.” American Educational Research Journal 55, no. 5 (October 1, 2018): 897–927. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218761337.

Goldhaber, Dan, Matt Kasman, Vanessa Quince, Roddy Theobald, and Malcolm Wolff. “How Did It Get This Way? Disentangling the Sources of Teacher Quality Gaps Through Agent-Based Modeling | CALDER.” CALDER Center, February 2023. https://caldercenter.org/publications/how-did-it-get-way-disentangling-sources-teacher-quality-gaps-through-agent-based.

Grubb, W. Norton. The Money Myth: School Resources, Outcomes, and Equity. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610446372.

Handel, Danielle V., and Eric A. Hanushek. “U.S. School Finance: Resources and Outcomes.” Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2022. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30769.

Hanushek, Eric. “Who Could Be against ‘Adequate’ School Funding?” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, June 23, 2004. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/who-could-be-against-adequate-school-funding.

Hanushek, Eric A. “The Failure of Input-Based Schooling Policies.” Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2002. https://doi.org/10.3386/w9040.

Hess, Frederick M., and Brandon L. Wright, eds. Getting the Most Bang for the Education Buck. New York: Teachers College Press, 2020.

Hong, Saahoon, and Kristy Piescher. “The Role of Supportive Housing in Homeless Children’s Well-Being: An Investigation of Child Welfare and Educational Outcomes.” Children and Youth Services Review 34, no. 8 (August 1, 2012): 1440–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.03.025.

Hyman, Joshua. “Does Money Matter in the Long Run? Effects of School Spending on Educational Attainment.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 256–80. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20150249.

Jackson, C Kirabo. “Does School Spending Matter? The New Literature on an Old Question.” In Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research Conference, 2018. https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.northwestern.edu/dist/b/3664/files/2020/11/Cornell_ overview_post_stamped.pdf.

Jackson, C. Kirabo, Rucker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico. “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, no. 1 (February 1, 2016): 157–218.https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv036.

Jackson, C. Kirabo, Rucker Johnson, and Claudia Persico. “The Effect of School Finance Reforms on the Distribution of Spending, Academic Achievement, and Adult Outcomes.” Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2014. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20118.

Jackson, C. Kirabo, Cora Wigger and Heyu Xiong. “Do School Spending Cuts Matter? Evidence from the Great Recession.” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24203/w24203.pdf.

Jang, Heewon, and Richard W DiSalvo. “How and Why Do Estimates of US Education Finance Progressivity Change with School-Level Finance Data?” EdWorkingPaper: 23-752, March 2023. https://doi.org/10.26300/wgf1-bs77.

Jarmolowski, Hannah, Chad Aldeman, and Marguerite Roza. “Do Districts Using Weighted Student Funding Formulas Deliver More Dollars to Low-Income Students?” Peabody Journal of Education 97, no. 4 (2022): 427–38.

Jimenez-Castellanos, Oscar and Lawrence O. Picus. “Serrano v. Priest 50th Anniversary: Origins, Impact and Future.” BYU Education & Law Journal, no. 1 (2022). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byu_elj/vol2022/iss1/2.

Knight, David S. “Are School Districts Allocating Resources Equitably? The Every Student Succeeds Act, Teacher Experience Gaps, and Equitable Resource Allocation.” Educational Policy 33, no. 4 (June 1, 2019): 615–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904817719523.

Kolluri, Suneal. “Advanced Placement: The Dual Challenge of Equal Access and Effectiveness.” Review of Educational Research 88, no. 5 (October 1, 2018): 671–711. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318787268.

Korecki, Natasha. “Illinois Overhauls System for Funding Public Schools.” POLITICO, August 29, 2017. https://www.politico.com/story/2017/08/29/illinois-public-schools-funding-242144.

Kozol, Jonathan. Savage Inequalities: Children in America’s Schools. New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2012.

Kruse, Kevin Michael. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Lafortune, Julien, Jesse Rothstein, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. “School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, no. 2 (2018): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160567.

Lee, Hojung, Kenneth Shores, and Elinor Williams. “The Distribution of School Resources in the United States: A Comparative Analysis across Levels of Governance, Student Subgroups, and Educational Resources.” Peabody Journal of Education 97, no. 4 (2022): 395–411.

Legewie, Joscha, and Jeffrey Fagan. “Aggressive Policing and the Educational Performance of Minority Youth.” American Sociological Review 84, no. 2 (April 1, 2019): 220–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419826020.

Levine, Phillip B., and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. “The Impact of Children’s Public Health Insurance Expansions on Educational Outcomes.” Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2009. https://doi.org/10.3386/w14671.

Maynard, Rebecca A., and Richard J. Murnane. “The Effects of a Negative Income Tax on School Performance: Results of an Experiment.” The Journal of Human Resources 14, no. 4 (1979): 463–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/145317.

Meier, Ann, Benjamin Swartz Hartmann, and Ryan Larson. “A Quarter Century of Participation in School-Based Extracurricular Activities: Inequalities by Race, Class, Gender and Age?” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 47, no. 6 (June 2018): 1299–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0838-1.

Miller, Corbin. “The Effect of Education Spending on Student Achievement: Evidence from Property Wealth and School Finance Rules.” Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association 111 (2018). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26939356.

Morgan, Ivy. “Equal Is Not Good Enough.” The Education Trust, December 2022. https://edtrust.org/resource/equal-is-not-good-enough.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021.” National Center for Education Statistics, March 6, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_236.55.asp.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021.” National Center for Education Statistics, March 6, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_236.55.asp.

Papke, Leslie E. “The Effects of Changes in Michigan’s School Finance System.” Public Finance Review 36, no. 4 (July 2008): 456–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142107306287.

Reyes, Jessica Wolpaw. “Lead Policy and Academic Performance: Insights from Massachusetts.” Harvard Educational Review 85, no. 1 (2015): 75–107. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.85.1.bj34u74714022730.

Roy, Joydeep. “Impact of School Finance Reform on Resource Equalization and Academic Performance: Evidence from Michigan.” Education Finance and Policy 6, no. 2 (April 2011): 137–67. https://doi.org/10.1162/EDFP_a_00030.

Saxena, Jaya. “The SAT and ACT Can Be Prohibitively Expensive for Some Students.” Vox, March 28, 2019. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/3/28/18282453/sat-act-college-admission-testing-cost-price.

Sparks, Sarah D. “Wealthier Enclaves Breaking Away From School Districts.” Education Week, May 1, 2019. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/wealthier-enclaves-breaking-away-from-school-districts/2019/04.

———. “Wealthier Enclaves Breaking Away From School Districts.” Education Week, May 1, 2019. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/wealthier-enclaves-breaking-away-from-school-districts/2019/04.

Teacher Incentive Allotment Website. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://tiatexas.org.

Tushnet, M.V. The NAACP’s Legal Strategy against Segregated Education : 1925-1950. University of North California, 1987. https://books.google.com/books?id=Bx7KzgEACAAJ.

Tyner, Adam. “The Relationship Between School Funding and Student Outcomes.” In Getting the Most Bang from the Education Buck, edited by Frederick M. Hess and Brandon L. Wright. New York: Teachers College Press, 2020.

Urban Institute. “School Funding: Do Poor Kids Get Their Fair Share?” May 2017. http://urbn.is/k12funding.

Urban Institute. “Which Students Receive a Greater Share of School Funding?” April 25, 2022. https://urbn.is/3Hk6P93.

Wang, Aubrey. “A Pre-Kindergarten Achievement Gap? Scope and Implications.” Online Submission 5, no. 9 (January 9, 2008): 23–31. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED503007.pdf.

Winsberg, Morton D. “Flight from the Ghetto: The Migration of Middle Class and Highly Educated Blacks into White Urban Neighborhoods.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 44, no. 4 (1985): 411–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3486871.

Yaluma, Christopher, and Adam Tyner. Is There a Gifted Gap? Gifted Education in High-Poverty Schools. Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, January 2018. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/there-gifted-gap-gifted-education-high-poverty-schools.

About the Report

This brief was made possible through the generous support of The Anschutz Foundation and our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. We are grateful to Chad Aldeman for his insightful feedback on various drafts of the brief. We also extend our gratitude to Pamela Tatz for copyediting. At Fordham, we would like to thank Adam Tyner for authoring the report; Chester E. Finn, Jr., Michael J. Petrilli, Amber Northern, and David Griffith for reviewing drafts; Victoria McDougald for her role in dissemination; Stephanie Distler for developing the report’s cover art and coordinating production; and Christian Eggers, Jeanette Luna, and Jamya Davis for research assistance.