- How might the SCOTUS decision on affirmative action in higher education also affect K–12 policy? —Education Next

- A college professor reflects on “racial gamification,” the byproduct of affirmative action. —The New York Times

- After years of decline, Chicago Public Schools student enrollment grew last year—due to immigration. —Chicago Sun-Times

- In Missouri, parents are questioning a law that could put them in jail if their kids aren’t in school “regularly.” —The Wall Street Journal

- In case you missed it, Governor DeWine signed the new state budget into law on Monday. Not too much coverage of education issues in the press as yet, although our own Aaron Churchill talked to the Dayton Daily News about the implications of near-universal eligibility for EdChoice vouchers which is now the law of the land. He also reminded folks that the budget increases oversight of private schools that take voucher students, but I fear that the audience who needed to hear that detail may have missed it over their own wailing lamentations. (Dayton Daily News, 7/3/23) This piece is almost entirely lamentations, especially regarding another big deal that became law with the signing of the budget bill: A change in K-12 education governance that will curtail the responsibilities of the state board of education, get rid of the Ohio Department of Education in favor of the Department of Education and Workforce (DEW), and move the state director of education (and workforce) into the executive branch. (Ohio Capital Journal, 7/4/23)

- Please don’t think I am slighting our news reporters for not being fully au fait with all the budget-related DEW-ings (see what I did there?). There is simply a lot going on these days for reporters and others to get a grip on. Case in point: The elected board that runs Youngstown City Schools (yes they do) acted very quickly indeed to elevate interim superintendent Jeremy Batchelor to the permanent gig this week without seeming to consider any other options or paths. All good, really, and par for the course. But I had to shake my head when one of his primary tasks was listed as “getting the district removed from state control.” Fine, I guess, but I hope they will at the same time think about some other tasks to give the new supe that might actually help students. (WKBN-TV, Youngstown, 7/3/23)

- Back here in the real world, the Catholic Diocese of Cincinnati announced last week that St. Joseph School will not reopen for the 2023-24 school year, ending 176 years of continuous service in the Queen City. The issue is at least $2.5 million of foundation and mechanicals work needed to make their 125-year-old building safe for use by students following the findings of an engineering assessment…although slow but steady enrollment declines are also part of the issue. We know that these sorts of issues play out very differently in school districts, but no state construction bonds or tax levy largesse are coming to support St. Joe’s. Instead, the staff are working hard this summer to make sure students find a new school for the fall. (Cincinnati Enquirer, 6/30/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

- Not much to talk about in this edition of the Bites except for the passage of the state budget bill which occurred late in the day on Friday. Lots of great K-12 education provisions made the final version. You can read a little about them in the Dispatch. And when I say “a little”, I mean it. (Columbus Dispatch, 6/30/23) There’s even less detail on the K-12 education provisions in the Dayton Daily News coverage. Too bad. (Dayton Daily News, 6/30/23) And while education provisions are the largest category in the budget breakdown reported by AP, K-12 only gets part of that section and most of those items are missing some important detail as I see it. All of the pieces are worth a read, but expect more and better analyses to come soon. There will be a whole lot more for us to talk about in the Bites then. (AP, 6/30/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? (And most of them are better than this one, I assure you!) Subscribe by clicking here.

Today, the Ohio General Assembly passed House Bill 33, the state’s biennial budget bill for FYs 2024–25. The legislation contains numerous provisions that strengthen K–12 education, among which include:

- Strengthens funding for Ohio’s public charter schools. The budget significantly increases funding for high-quality charters, while also creating a new funding supplement for all brick-and-mortar charters. Historically, charters have been funded at just 70 percent of districts’ overall funding. Through this budget, the average charter will receive approximately 85 percent of district funding; high-quality charters, roughly 90 percent.

- Expands private-school choice to all Ohio families. All parents will now be eligible for the state’s EdChoice scholarship. Full scholarship amounts will apply when households earn 450% or less of the federal poverty level; above that threshold, amounts are smaller.

- Increases accountability for the state education agency through much-needed governance reforms. These include making the agency director a gubernatorial appointee, reducing the role of the state board of education, and increasing the emphasis on workforce initiatives.

- Ensures that schools use high-quality literacy curricula. The budget requires schools to adopt practices aligned with the science of reading—an approach that stresses phonics and other key elements of effective literacy instruction. It also sets aside millions in funding to support curricula overhauls and professional development.

“State lawmakers have taken historical strides forward to empower families and improve schools,” said Aaron Churchill, Ohio Research Director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “With this budget in place, Ohio parents will have more quality educational options within their reach, be they district schools, public charter schools, or private schools. When parents are engaged and able to access schools aligned with their needs and expectations, children reap the benefits.”

As for the governance and literacy components, Churchill added, “Through a bold overhaul of the department of education and strong literacy reforms, the legislature has laid the groundwork for higher student achievement. More coherent leadership at the state level will promote rigorous implementation of policies that aim to improve education. The budget’s literacy initiatives will ensure that all children—no matter where they attend school—learn to read using proven, effective instructional methods.”

Governor DeWine is expected to sign the final budget bill shortly.

Budget conference committee continues

As we go to press, House and Senate conferees on the state budget bill are still working toward consensus on a number of provisions before the full bill can be voted on by both chambers. We discussed last week several of the biggest issues related to charter schools, and there are a number of other big picture items, including a wholesale revamp of K-12 education governance, to keep an eye on as the bill is finalized and ultimately signed into law.

Student transportation changes for next year

We have also discussed some important changes to school transportation policies which could also be part of a final budget bill. The state’s proposed changes can’t come soon enough, given the uncertainty about transportation that remains in districts such as Dayton less than two months before the start of the new school year. The indecision of district officials could affect not only district students, but also those attending charters, private schools, and STEM schools in the area.

Research and the reality on the ground

A recent issue brief from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools digs into the data around alternative education campuses (AECs). That is, school buildings dedicated to serving students who are at high risk of dropping out of school—or have already done so. Charter AECs, overall, appear to outperform their district-run counterparts, but the brief’s authors explain that student success should likely be viewed differently for students in AECs than it is in traditional educational settings. In Ohio, such charter schools are called “dropout prevention and recovery schools”, and while their programming is accurately reflected in the research, reading about the day-to-day work of students and teachers at Flex High School in Cleveland—as in this profile piece—gives readers a far more intimate view of the model.

Welcome aboard

The Mid-Ohio Educational Service Center (MOESC) this week announced their new Director of Community Schools. David Jones joins MOESC from the Franklin County Data Center and will take over sponsorship duties for two charter schools—GOAL Digital Academy and Tomorrow Center—on August 1. Congratulations!

U.S. Supreme Court action

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the Peltier v. Charter Day School case, effectively upholding a lower court ruling on the matter. While the impetus for the case was a dispute over a dress code requirement for girls at a North Carolina charter school, the lower courts had to address weightier issues of whether charter schools are “state actors.”. Following the court’s announcement, NAPCS president and CEO Nina Rees said in a statement, “The actions of the high court affirm that as public school students, charter school students are entitled to the same federal protections as their counterparts who attend district schools.”

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

- “In general, I think most superintendents earn their compensation,” says Fordham’s Aaron Churchill in this Dayton Daily News coverage of the pay and benefit structures for school chiefs in Ohio. He notes the big deal, high-pressure decisions they must make on the daily, adding, “A superintendent that can provide that type of strong leadership, while navigating political challenges, is worth every penny.” I suspect that someone on staff at the DDN disagrees with Aaron, based on the fact that a section discussing retirement plan contributions is headed “Other Kickbacks”. Ouch. (Dayton Daily News, 6/29/23)

- Speaking of district leaders, the superintendent of Columbiana Exempted Village School District is said to be super pleased with test score data from this spring, noting that even the lowest proficiency rate achieved was pretty good—75 percent of fourth graders were tested proficient or above in ELA—and well above the state average for that test. How’d they manage this feat? Supe told his elected school board members that it’s due to teaching, testing, reteaching, retesting, etc. until teachers are reasonably certain that kids have the material down. Genius, right? (The Morning Journal, 6/30/23) Also seemingly super pleased with stuff—all the stuff—is the superintendent of Beachwood City Schools, as he reports on the awesomeness of his district in a guest column for the CJN. I don’t know just how bougie this district really is, but reading the piece, I feel like they might want to integrate their mission statement fully into their branding and replace the Bison mascot with The Intellectual Entrepreneurs. Now wouldn’t that strike terror in the hearts of opponents on the gridiron and elsewhere? (Cleveland Jewish News, 6/29/23)

- Kudos from me (and probably only from me) to the elected school board of Akron City Schools who voted last night to hire their new superintendent from outside the district. It took six hours of deliberation and required two votes (for some reason), but their big ol’ search actually found them some new blood—Dr. C. Michael Robinson Jr., currently the chief academic officer for East Baton Rouge Parish Schools—and, likely, some brand new ideas for how to do business. (WKYC-TV, Cleveland, 6/29/23)

- Sticking with our theme of school leadership for one more clip: Here’s part one of a two-part farewell interview with CMSD CEO Eric Gordon. His last day after 12 years at the helm in Cleveland is today. (Signal Cleveland, 6/29/23)

- And speaking of things that have been around a long time in Ohio education circles (were we?), here’s a brief press release announcing that computer systems that have been utilized by nearly all district and charter schools across Ohio to manage all fiscal and payroll operations for forty years have finally been decommissioned. The “obsolete” and “retired” systems have been replaced over the last five years with “a robust, modern” app-based system in 766 Ohio school districts and charter schools. Yowza! (PR Newswire, 6/30/23)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

It’s been a very busy budget season in Ohio. Issues including private school choice eligibility, charter funding, and the state’s third grade reading retention requirement have drawn the lion’s share of attention, and when the budget is finalized, these items will likely be the primary bullet points in any summary coverage. As they should be, as they’ll impact thousands of students.

But there’s an under-the-radar provision related to Academic Distress Commissions that first appeared in the Senate’s version of the budget that could also have big implications. If left untouched by the conference committee and the governor’s veto pen, this provision would dissolve the Lorain City School District’s Academic Distress Commission, as well as the district’s state-required academic improvement plan. In doing so, it would remove the district from state oversight for the first time in over a decade. This would be a major mistake.

To understand why this is a big deal, some background is needed. Academic Distress Commissions (ADCs) were first created in 2007 as a way for the state to intervene in districts that consistently failed to meet academic standards. In 2015, after failing to generate much improvement, the state strengthened the law by boosting the authority of ADCs and empowering an ADC-appointed CEO with significant managerial authority to create and implement a rigorous turnaround plan. After years of lobbying, Ohio lawmakers caved to political pressure in the summer of 2021 and created an off-ramp for the three districts under an ADC: Youngstown, Lorain, and East Cleveland. As part of the deal, each district’s board was tasked with developing an academic improvement plan containing annual and overall improvement benchmarks. If districts met a majority of these benchmarks by June 2025, their ADC would be dissolved.

Or at least that’s what was supposed to happen. The tiny budget provision introduced in the Senate dissolves Lorain’s ADC and its academic improvement plan. The district will no longer be required to demonstrate that they’re improving on behalf of their students. Their counterparts in Youngstown and East Cleveland, however, weren’t given the same free pass.

Unsurprisingly, the education establishment in Lorain is rejoicing over their special treatment. But for the rest of us, this carve-out raises some troubling questions. Why, after establishing an off-ramp during the previous budget cycle, did lawmakers suddenly decide to change course? Why did they change their minds for only one district? And what could possibly justify letting a district that’s performed so poorly for so long that it’s been under state oversight since 2013 go back to business as usual?

The only acceptable answer to any of these questions is improved student outcomes. If officials in Lorain could prove to state lawmakers that, based on reliable and comparable academic measures, their schools were rapidly and consistently improving—and if Youngstown and East Cleveland couldn’t do the same—that might justify Lorain’s special treatment.

The problem is that Lorain hasn’t had enough time to claim that its schools consistently improved. The 2022–23 school year, Lorain’s first year implementing their academic improvement plan, ended on May 31. The Senate added the Lorain ADC amendment to its budget roughly two weeks later. Could district officials have gathered enough evidence in that time to prove to lawmakers that their first year under a self-designed improvement plan had been a rousing success? Possibly. Many of the benchmarks in their plan are based on iReady and other locally-calculated measures, rather than on state exams and school report cards. That means district officials didn’t have to wait around for state test results. (Lorain’s decision to focus on local measures that aren’t easily comparable to other districts is worth pointing out.)

But even if lawmakers did consider data from the locally-calculated measures included in Lorain’s plan, and even if those results were positive (they don’t seem to be publicly available), it would still only be one year’s worth evidence. Despite what the district has tried to claim, one year of progress doesn’t prove much. To responsibly dissolve an ADC, lawmakers should need several years’ worth of data. There’s no other way to ensure that the improvements are real and sustainable, and not just a fluke. After years of underperformance, years of improvement are needed.

But what about state exam results from 2018–19, 2020–21, and 2021–22? Those data cover more than just one year. But they don’t show the kind of significant improvement that could justify letting Lorain exit state oversight early.

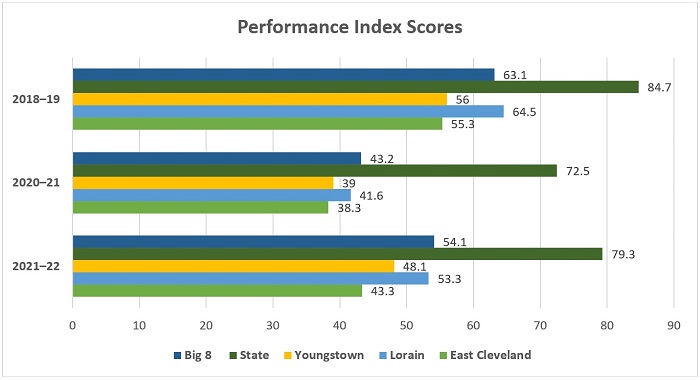

Consider the table below, which illustrates performance index scores in ADC districts, with averages from the state and the Big Eight districts included for comparison. Like its ADC and Big Eight counterparts, Lorain saw huge drops in student achievement during 2020–21. But there was also a bounce back the following year. Lorain’s performance index score for 2021–22 wasn’t just better than their prior year performance, it was better than that of Youngstown and East Cleveland, and pretty close to the Big Eight average.

Lorain deserves kudos for recovering some of that lost ground. But it’s also important to note that the district still hadn’t bounced back to pre-pandemic levels, which were troublingly and persistently low to begin with. Data from the recently finished school year, 2022–23, would go a long way toward determining whether Lorain is actually getting better, and not just recovering ground lost during the pandemic. Unfortunately, state lawmakers opted not to wait for that.

Achievement isn’t the only state report card measure that’s worthy of consideration. Ohio’s progress component, which measures the academic growth students make over the course of a year, is also crucial. It yields results that are more neutral regarding demographics, making it possible for districts where students are far behind in reading and math to showcase their contribution to student learning and reveal positive academic growth. Lorain earned a four-star rating on this component during 2021–22, which means students made more progress than expected. That’s an excellent start that the district’s teachers and students should feel great about. But it’s still just a start. Without additional years of data, lawmakers have no way of knowing whether the progress will continue.

And then there’s early literacy. For school report cards, the state tracks three measures and combines them to create an overall early-literacy rating for districts and schools. During the 2021–22 school year, Lorain earned just one star in early literacy. Only 28 percent—less than one third—of its students were proficient on the reading segment of the third grade English language arts state test. Furthermore, the district moved only 10 percent of its students from off- to on-track in reading. Given the heavy emphasis that the governor and lawmakers in both chambers placed on early literacy during this budget cycle, one would think that Lorain’s horrific performance would give state leaders pause. Sadly, that doesn’t seem to have entered the calculations.

***

We have no way of knowing why lawmakers suddenly decided to let Lorain off the hook. Given the data outlined above, it seems highly unlikely that they were wowed by sizable and sustainable academic improvements because little evidence of improvement exists. There hasn’t been enough time for Lorain to prove itself under its improvement plan.

State lawmakers have a moral obligation to ensure that students receive a quality education. Giving Lorain a pass in this way abdicates that responsibility—not because Lorain deserves to be “punished,” but because it had decades worth of poor performance in its past that has negatively impacted generations of students and the community. Easing up the pressure—as weak as it may be—will do nothing to improve student learning in Lorain.

America’s school choice moment has finally arrived, but the vast majority of students nationwide (84 percent) still attend traditional public schools—and will for the foreseeable future. Conservatives would be wise to support policies that give families choices within the public education system. Cross-district open enrollment does precisely that, and it has strong bipartisan support.

Indeed, the opposite of open enrollment, residential assignment, is among public education’s most antiquated practices. Students’ public schools are determined based on where they live. School district attendance zones often reflect the legacy of the discriminatory and now-illegal boundaries imposed by housing redlining. The federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration reinforced racial segregation, codifying preexisting boundaries set by developers and homeowners associations decades ago.

For many, residential assignment is an insurmountable barrier to better educational opportunities. These government-imposed geographic lines fracture communities by inextricably linking housing and schooling. Families are pressured to sacrifice valuable goods, such as living near their family, friends, and churches, to guarantee they have access to quality public schools. Ironically, this means that many families sometimes sacrifice the invaluable voluntary associations Alexis de Tocqueville described as essential to the American experiment in favor of government-imposed ones.

Furthermore, residential assignment maintains public school districts’ monopoly over students by limiting parents’ ability to hold schools accountable. Unless they can afford to pay private school tuition—or move across town—families have no leverage to pressure their district schools to improve or be responsive to their desires. To tip the balance of power toward students and families, education dollars should follow students to any school, public or private, just as Milton Friedman envisioned.

In 1980, Friedman and his wife, Rose, explained that in a system with school choice, a public school’s enrollment “would be determined by the number of customers it attracted, not by politically defined geographical boundaries or by pupil assignment.” While open enrollment would not eliminate residential assignment, it would weaken the boundaries that arbitrarily sort students into schools, representing an essential step toward the education marketplace the Friedmans described.

It would also benefit students and school districts. First, studies consistently show that students tend to transfer to higher-performing school districts when given the opportunity. For example, a study of Wisconsin’s open enrollment program found a positive relationship between districts’ state test results and student-transfer inflow, with separate analyses showing similar findings in California, Colorado, Minnesota, and Texas.

Research also shows that students transfer schools for various reasons, indicating that open enrollment can help them access their best-fit education. Separate evaluations of California’s District of Choice program by the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) found that students participate in open enrollment to escape bullying and access curricula, instructional philosophies, and other programs that aren’t available in their home districts. In its latest analysis, LAO reported that participating students “gained access to an average of five to seven courses not offered by their home districts” across several course types, including Advanced Placement and career technical education.

Open enrollment can also have positive competitive effects, with the Reason Foundation’s Wisconsin study finding that districts that lose students also post modest signs of improvement in the two years following enrollment losses. California’s LAO evaluations provide evidence of students’ home districts taking steps to better engage their communities and pursuing reforms to reduce student attrition, such as addressing programmatic concerns and improving access to within-district school transfer options. These efforts appear to work. Many of these school districts saw reductions in the number of students transferring out and improved their test scores over time. This shows that public school competition can foster excellence, making open enrollment the tide that raises all boats.

Fostering robust open enrollment isn’t easy, however. It requires both strong policy and portable education funding. State policymakers must overhaul their student-transfer laws so that students are guaranteed tuition-free access to any public school across their state, with few exceptions—primarily, that a school is full or overcrowded and cannot accept more students. These revamped policies should establish clear expectations for school districts and ensure that timelines, school-level capacity, and other important information are easily accessible to parents and all stakeholders.

State education agencies should be required to collect and report key open enrollment data at the school district level, including the number of transfer applications received, reasons for rejecting transfer applications, and number of transfer students enrolled. Policymakers must also ensure that state and local education funding follows students to the schools of their choice. Otherwise, school districts might have financial incentives to block transfer students who live outside their boundaries. This problem is unique to each state, but Wisconsin serves as a good example of how one state successfully addressed it with a straightforward policy solution.

Editor’s note: This is a modified excerpt of the authors’ American Enterprise Institute policy brief “The Conservative Case for Public School Open Enrollment” (June 2023).

Parents and policymakers inured to years of depressing headlines about learning disruptions in the wake of the pandemic might be tempted to shrug at the latest federal test data on the achievement of thirteen-year-olds as more of the same. This would be a colossal mistake. The new figures contain three terrifying findings—about the magnitude of the achievement declines, the abysmal failure of ongoing recovery efforts, and the likely persistence of these impacts on future cohorts of students.

Consider each of these in turn.

The new test score data from National Assessment of Educational Progress are unusual in that they put the results in the context of five decades’ worth of student performance. And the numbers are truly dire: In reading, average scores have declined to levels last seen in the 1970s, erasing decades of progress won through political blood, sweat, tears—and billions in public investments.

But the scores among the most disadvantaged students are even more shocking. Those in the bottom quarter of achievement are less proficient in reading than similar-aged peers were in 1971, posting the lowest scores ever recorded. In math, the bottom 10 percent students are back to their all-time low. Although racial breakdowns are not available for earlier years, the gap between Black and White students has grown markedly over the past decade. Not only has average achievement posted a record decline, but the effects have been concentrated among the most-at-risk students.

The second piece of bad news is about the persistence of these learning losses despite several years of concerted effort. The latest NAEP scores are based on assessments administered between October and December 2022. That means the record-low achievement continued to be observed nearly two years after most schools reopened for in-person learning—after two years of much-heralded summer schools, intensive tutoring and other academic supports—and despite nearly $200 billion in emergency federal education spending. Just last year, the White House asserted that “states and school districts have the resources they need, and are required to address the impacts of the pandemic on students’ learning.” Clearly, the new data show that they have failed to do so.

While it is possible that achievement would’ve been even lower were it not for these efforts, it is also clear that what school districts have tried so far falls well short of what students need to get them back on track. With supplemental federal aid ending soon, and the recent debt ceiling deal taking additional funding off the table, the future looks even more distressing.

The NAEP data also shed new light on why learning losses are so difficult to reverse: record chronic absenteeism. A survey taken with the exam last fall showed that only 75 percent of thirteen-year-olds reported missing two or fewer days of school in the previous month, and the number of students absent for a week or more during that same period had doubled since the pandemic began.

Sharp drops in attendance were one of the earliest academic warning signs that emerged when schools reopened, but they were easily dismissed. Initially, many blamed Covid-related illnesses. During the 2021–22 academic year, some pointed to quarantine rules that kept students home for two weeks following close contact with ill classmates. Yet neither factor can explain why attendance problems remain.

It seems clear that widespread absenteeism has become a new normal, perhaps reflecting well-meaning efforts among educators and administrators to show empathy during the pandemic, an erosion of social norms about the importance of attendance or persistence of bad habits—such as late-night gaming and sleeping late—that many kids likely developed during months of prolonged closures or virtual instruction. The danger is that these norms continue not only among older students whose learning was disrupted, but also among younger kids who have begun kindergarten over the past two years in a world where absenteeism is tolerated and overlooked.

While proponents of mastery learning are surely right that time in the classroom does not guarantee learning, it seems obvious that students who do not attend school at all are probably not going to learn much.

In an ideal world, the latest NAEP data would serve as an overdue wakeup call for adults, whose own interests and priorities in education policy over the past two years seemed to have shifted from academic recovery to culture wars.

Consider the latest battles over LGBT-themed books in school libraries. Reasonable people can disagree about how to balance legitimate concerns surrounding age-appropriateness of reading materials with a desire to ensure that library offerings reflect students’ diverse experiences. But in a rational world, both sides would surely agree that these debates are of secondary importance to record-low literacy rates and the fact that nearly a third of thirteen-year-olds now report that they read for fun “never or hardly ever”—up sharply from a decade ago. Unless adults are willing to call a truce in their culture wars and focus on getting students to read anything and to read better, we are unlikely to make much progress in reversing the achievement declines.

The sad reality is that it is probably too late to help the oldest students. Recent high school graduates and those who will graduate over the next several years are almost certain to be the least prepared to enter the labor market or college in several generations. Public policy must be prepared to deal with the consequences of our society’s collective failure to undo the damage.

But it is not too late to help younger students. The concerted, bipartisan response that followed the 1983 publication of A Nation at Risk, which put concerns about low student achievement on the national political agenda in a serious way for the first time, provides a template. That report ushered in two decades of reforms that focused on establishing high academic standards, greater accountability, and a focus on the lowest achievers. It is no coincidence that NAEP scores increased and achievement gaps narrowed during these years.

Efforts to help students recover from the pandemic have not matched the same level of urgency, focus or efficacy. The new federal data send a clear message that we must do better.

Editor’s note: This was first published by The 74.

Cheers

- “Instead of objectively evaluating what actually works, educators fell in love with the utopian idea that children would naturally learn to read if only teachers made reading fun. In reality, most children need explicit phonics instruction.” —Eva Moskowitz

- In response to job market demands, Texas is seeing growth in technical college and career programs, apprenticeships, and workforce training for students with disabilities. —Texas Tribune

Jeers

- Implementation challenges and parents’ misunderstanding are impeding learning recovery efforts and showing up in plummeting NAEP scores. —Marty West

- “Book bans, chatbots, pedagogical warfare: What it means to read has become a minefield.” —The New York Times