Last week, I provided sobering evidence of the “excellence gap” among twelfth grade students—the sharp divides along lines of race and class in achievement at the highest levels.

Now I want to make the case that early elementary school is the optimal time to attack that gap—and that high school, middle school, and even upper elementary school are mostly too late.

That’s because the under-representation of Black, Hispanic, and poor students at high levels of academic performance doesn’t suddenly appear in high school. Rather, it is apparent on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) all the way back to fourth grade.

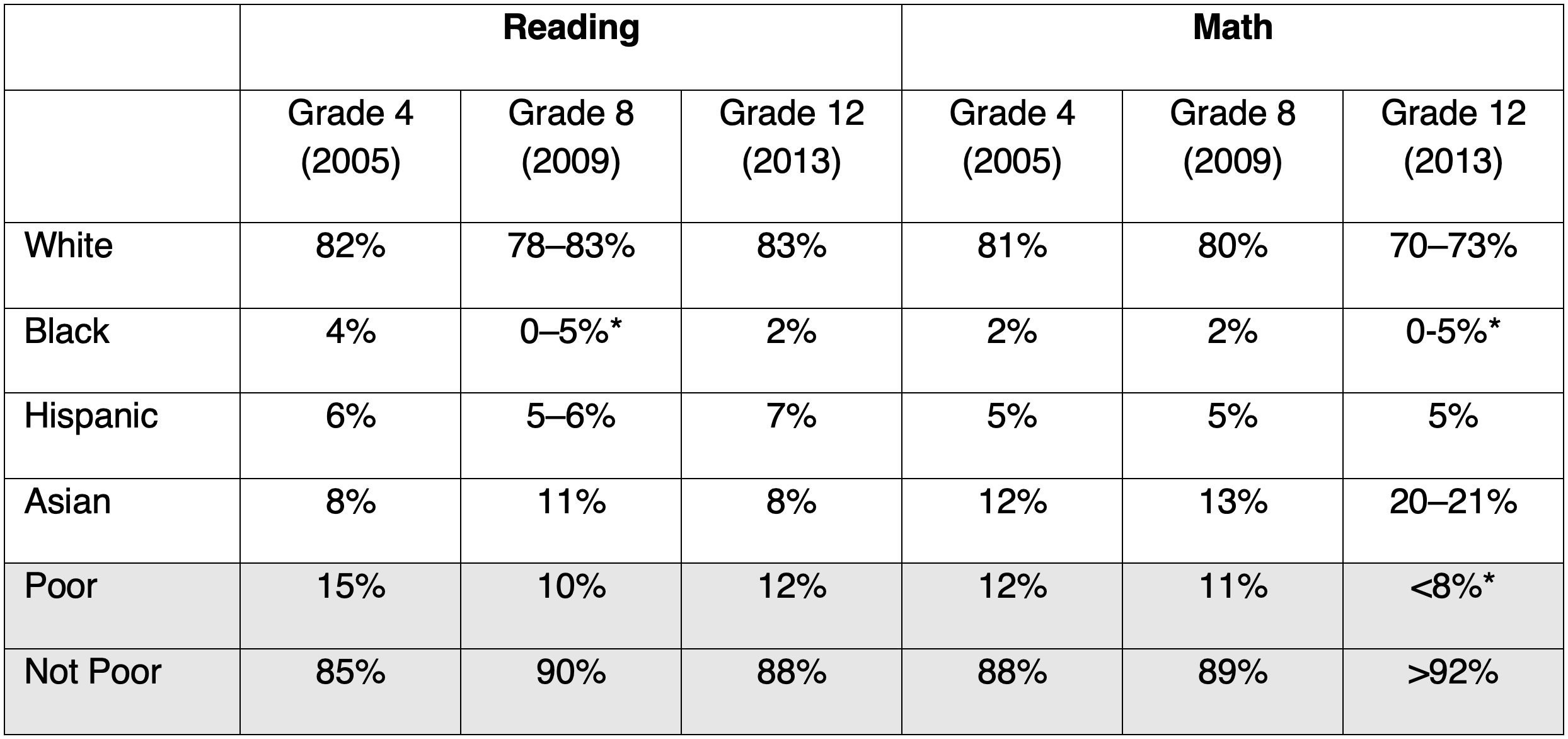

Here’s what that looks like when using achievement at the Advanced level on NAEP as the metric.

Table 1: Composition of students scoring “Advanced,” high school class of 2013

* Fewer than 1 percent of students scored at Advanced.

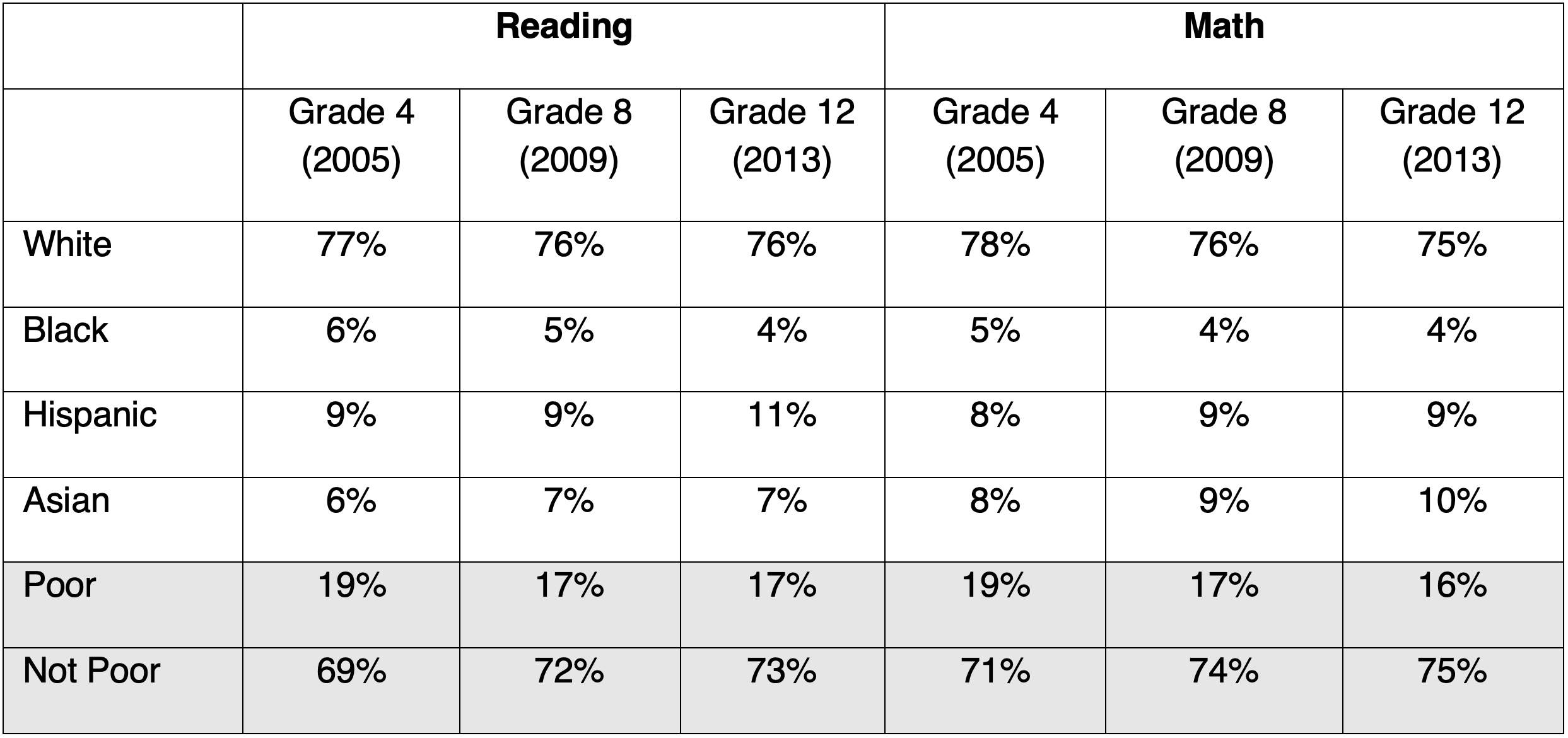

And here’s what that looks like when using achievement at the top quartile in performance as the metric.

Table 2: Composition of students scoring in top quartile, high school class of 2013

The story is the same: remarkable consistency across the grade bands, with modest declines for Black and poor students over time, especially in reading, and a surge in high school in the proportion of Asian students achieving at the highest levels in math.

As with the twelfth grade data I reported last week, the numbers for the fourth and eighth grade are devastating for Black and Hispanic students. At both grade levels and in both reading and math, 5 percent or fewer of the students scoring Advanced were Black; 6 percent or fewer of the top-quartile students were Black. The numbers for Hispanic students were only slightly better.

To me, this indicates that it’s mostly—mostly, not entirely—futile to blame the excellence gap on high schools or middle schools. To be sure, they could be doing more to close the gap—to help low-income, Hispanic, and Black students achieve at higher levels. Indeed, some fantastic schools, including several in the charter sector, do precisely that. And the modest declines for Black and low-income high-achievers between grades four and twelve is absolutely something that our middle and high schools could and should be addressing. (Those declines are also apparent on other assessments and in other studies.)

But it’s simply common sense that it’s more feasible to keep the excellence gap from widening in the first place than trying to fix it when students are older. Indeed, this is true for most challenges in K–12 education.

Roll back the tape to kindergarten

Let’s take it one step further, then, and look at “academic achievement” at the kindergarten level. That’s possible thanks to the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS). This ambitious data collection program followed two waves of students, the first a group that started kindergarten in 1998 and graduated high school in 2011. That’s not the precise cohort of students we’ve been tracking so far—the one that graduated from high school in 2013, and was in college in 2015–16—but it’s close enough for our purposes.

The kids in the study took tests every year from grades K–5, and their parents and teachers filled out extensive surveys, as well. We know a lot about these students. In the fall 1998, officials gave the study participants an age-appropriate assessment—read aloud by a teacher—that tested basic school readiness skills in literacy and numeracy at kindergarten entry.

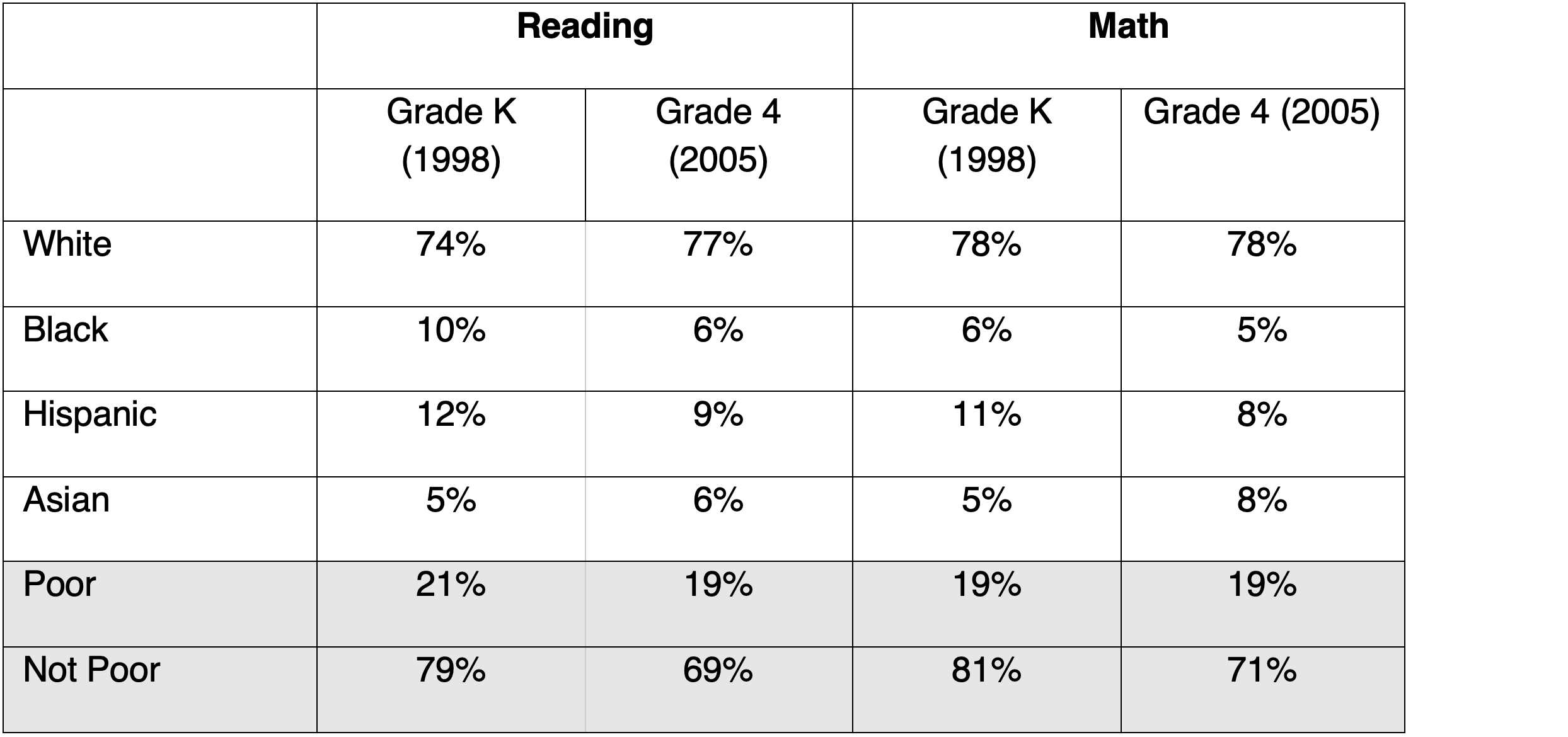

The ECLS project didn’t have an equivalent to an “Advanced” level of performance, but it did break down results by quartile. Let’s add that to the picture:

Table 3: Composition of the group of students who scored at the top quartile in reading, ECLS-K vs. fourth grade NAEP

Source: U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. America's Kindergartners, NCES 2000-070, by Kristin Denton, Elvira Germino-Hausken. Project Officer, Jerry West, Washington, DC: 2000. Note: For the Kindergarten data, poor is defined as having ever used the AFDC program.

What stands out here is the big decline in the proportion of advanced readers who were Black between kindergarten and the fourth grade—from 10 percent to 6 percent. (There was a similar, if not as pronounced, pattern for Hispanic students, going from 12 percent to 9 percent, and poor students from 21 to 19 percent.) Ten percent still isn’t great (Black students made up 15 percent of the ECLS sample), but it’s a whole lot better than the 4 percent that’s still in the top-quartile reading group by twelfth grade.

Paradoxically, the decline between the start of school and the fourth grade is a bit of good news. After all, if the kindergarten scores were just as devastating as the twelfth grade ones, we might conclude that there was little the K–12 system could do; that everything that mattered to high achievers happened (or not) between ages zero and five. And yes, those years matter a lot! But so do the early elementary years, or so these data imply. Something is happening in grades K–4 that is causing a significant portion of Black, Hispanic, and poor high achievers to “lose altitude.” If we can identify that something, we can fix it.

We already knew that early elementary is a critical time for students in general. Consider, for example, the longstanding evidence demonstrating that gains made by poor students in Head Start and other pre-k programs tend to fade out during those years. Or studies showing that Black, Hispanic, and poor students make less progress, on average, from K–3 than their peers. Now we see that they matter tremendously for high achieving Black, Hispanic, and poor students, as well.

In my next post I’ll explore what might be causing the drop-off in Black and poor high achievers between kindergarten and the fourth grade, and what might be done to reverse it.