Starting in the early 2000s, with the implementation of No Child Left Behind, federal law required states to ensure that all public school teachers were “highly qualified.” That meant having a bachelor’s degree, full state certification, and subject-area mastery, often determined by a content test.

When ESSA was enacted in 2015, the highly qualified designation became a thing of the past. The new law requires states to set their own definition of a qualified teacher, and Ohio did that via Senate Bill 216 last year. The law requires public school teachers to be “properly certified or licensed,” which means they must possess one of the state’s approved teacher licenses.

For traditional districts, this change will have little impact. The vast majority of their educators enter the classroom with an Ohio teaching license thanks to one of the state’s many teacher preparation programs.

But it’s different for charter schools, many of which employ nontraditional teachers who have a bachelor’s degree but did not attend a conventional training program. Because these educators don’t enter the classroom the usual way, they tend to work under long-term substitute licenses until they meet state requirements for traditional or alternative licensure. Charters also use long-term substitute licenses to place teachers into hard-to-fill grade levels or subject areas and to increase the diversity of their workforce.

In short, charters rely a great deal on long-term substitute licenses. These are permitted by state law and were used extensively under No Child Left Behind’s “highly qualified” teacher framework, but the Ohio Department of Education has interpreted SB 216 to mean that teachers working under a long-term substitute license are not considered properly certified teachers. So unless something changes prior to the law going into effect in July, Ohio’s charter schools are about to lose a vital aspect of their hiring and recruitment flexibility.

Fortunately, the proposed state budget offers a simple fix. It eliminates the requirement for charter school teachers to be properly certified or licensed by the state. In addition to evidence being mixed on whether teacher licensure predicts classroom effectiveness, there are few reasons why that’s a good idea.

Autonomy in exchange for accountability

Buckeye charters are bound by the same accountability provisions as traditional district schools, including state report cards and federal sanctions. But they are also subject to additional measures, including an automatic closure law, which requires schools to permanently close after multiple years of poor performance, and the state’s sponsor evaluation system, which incentivizes authorizers to pay close attention to academic results. These tough accountability provisions ensure that persistently low-performing charter schools don’t stick around indefinitely, which is good news for kids, families, and communities. They also provide charter school leaders with a strong incentive to hire the very best teachers, regardless of whether they’ve gone through state regulatory hoops, because ineffective teaching lowers school ratings and risks closure. It therefore makes sense to grant them more hiring flexibility. (Keep in mind, too, that charters have more flexibility to swiftly dismiss poor-performing teachers without going through the bureaucratic procedures districts are subject to.) This is the grand bargain of charter schooling in action: stricter accountability in exchange for greater autonomy and flexibility in how schools build teams of great educators.

Competing for talent

Back in 2016, Fordham conducted a survey of leaders from the highest-performing Ohio charter schools. More than half noted that they “generally struggle” to find good teaching candidates, and that teacher pay is a main reason: 71 percent claimed that charter schools will always be at a serious disadvantage because they cannot afford to offer competitive salaries.

Low teacher pay is a direct result of the state’s inequitable charter school funding. Ohio charters, on average, receive 28 percent less funding than nearby school districts. The best way to address the issue is to fund charters equitably, and the governor and lawmakers are thankfully starting to work on that. But such a policy change is expensive and likely to be quite limited for the foreseeable future. In the meantime, state lawmakers should commit to leveling the recruitment playing field for charters as much as possible—and that means not restricting their hiring practices to those favored and dominated by traditional districts.

Attracting high-quality charter networks to Ohio

Ohio is home to top-notch homegrown charter networks like Breakthrough, Graham, KIPP, United Schools Network, and DECA. These schools do tremendous work for students and communities and are gradually expanding, but they only educate around 3 percent of the pupils in Ohio’s largest cities, and their forecasted growth won’t be enough to meet increasing demand for quality choice. Out-of-state networks with a résumé of excellence could help close the gap, but they won’t be tempted to open in Ohio unless the state becomes a more attractive market. Lawmakers could remedy this by funding charters more equitably and freeing them to recruit, hire, and train talented individuals who fit their missions. The schools would still be held to rigorous accountability measures, but these changes would make Ohio far more appealing to stellar nationwide networks.

***

To be clear, exempting charters from certification or licensure requirements wouldn’t result in a free for all. Teachers would still need college degrees, be subject to background checks, and, importantly, have to answer for the performance of their students on state tests and report cards. It merely maintains charters’ freedom to hire nontraditional teachers and assign them to a wider range of grade levels and subject areas. Skeptical lawmakers could even add safeguards, like requiring teachers to pass academic content licensure tests to prove their subject mastery. But limiting the flexibility of charter schools without hard evidence that it will benefit kids shouldn’t be an option.

Editor’s Note: Back in September 2018, awaiting the election of our next governor, we at the Fordham Institute began developing a set of policy proposals that we believe can lead to increased achievement and greater opportunities for Ohio students. This is one of those policy proposals.

With Mike DeWine sworn in as Ohio’s 70th governor, and with his administration now well underway, we are proud to roll out the full set of our education policy proposals. You can download the full document, titled Fulfilling the Readiness Promise: Twenty-five education policy ideas for Ohio, at this link, or you can access the individual policy proposals from the links provided here.

Proposal: Streamline the state funding formula by eliminating the Targeted Assistance, Capacity Aid, and the bonus funding components, and merge those funding streams into the Opportunity Grant.

Background: School funding has long been a joint state-local responsibility. In 2017, Ohio districts generated roughly $9 billion in local tax revenue, with wealthy districts able to raise more. Meanwhile, the state contributes $10 billion-plus and distributes more funds to Ohio’s neediest districts to compensate for their lower taxing capacities. To allocate the bulk of state aid, lawmakers first set a formula, or “base,” amount ($6,010 per student in FY 18). This base is then adjusted by the State Share Index (SSI), which accounts for districts’ income and property wealth. Together, the base amount and SSI determine districts’ Opportunity Grants, which are the core of Ohio’s foundation funding program (table 1). Additional components are layered on top, such as Targeted Assistance, Capacity Aid, various student-based categories, and bonus funds. Some of these additional components are essential to equitable state funding; for example, Ohio adds funds when schools serve special-education students or students with limited English proficiency. Other components, such as Targeted Assistance and Capacity Aid, are less necessary to achieving funding-equity goals yet increase the complexity of the funding system. Moreover, unlike the Opportunity Grant, which provides a certain amount of state aid to all districts, not everyone receives funds under Targeted Assistance and Capacity Aid. In 2017, ninety-three out of 610 districts were denied Targeted Assistance, and 308 were denied Capacity Aid.

Table 1: Main components of Ohio’s foundation funding program, traditional districts, FY 2017

Source: ODE, Foundation Settlement Report (FY 2017, June 2 Payment).

Proposal rationale: The Opportunity Grant, Capacity Aid, and Targeted Assistance have overlapping purposes: all aim to drive more dollars to districts with limited funding capacity. By collapsing these similar components into the core Opportunity Grant, the state would create a less complicated formula that is easier to predict, while also maintaining a focus on equity between districts. Centering attention on the Opportunity Grant would also allow the state to concentrate on its design and functionality, rather than having to review multiple calculations. Meanwhile, the bonus components spread too little funding across all districts to incentivize any real improvements; those dollars would be better allocated via the Opportunity Grant.

Cost: The proposal rolls existing dollars into the Opportunity Grant and, in isolation, would not cost additional state money. However, districts’ state funding levels would change, and hence the proposal would likely interact with caps and guarantees; fiscal modelling should be undertaken to predict costs.

Resources: For more on merging funding streams into the base funding, see the Foundation for Excellence in Education’s paper Student-Centered State Funding: A How-To Guide for State Policymakers (2017); this idea is also part of the school-funding proposals in Ohio House Bill 102 of the 132nd General Assembly. For a relatively broad description of the state funding system, see A Formula That Works: Five Ways to Strengthen School Funding in Ohio, a report written by Bellwether Education Partners’ Jennifer Schiess and colleagues and published by the Fordham Institute (2017). For detail on district-funding calculations, see the ODE report School Finance Payment Report (SFPR): Line by Line Explanation (2018).

- There are several questions and a ton of out-of-date information in this piece looking at graduation requirement changes over the last few years in Ohio from the perspective of some small-town teachers and administrators. On the question front, why complain about changing requirements when it is you who has been insisting on the changes? You just don’t like tests, folks. Insisting that we shouldn’t use them because your kids can’t pass them is old thinking and beneath you as educators. As for old news, I think that many of those avenues for changing the grad requirements to your favored flavor became dead ends a good while ago. But shhhh…. Don’t tell ‘em. (The Tribune-Chronicle, 4/28/19)

- Ditto for this commentary piece which conflates funding and academic distress in a flat word salad tossed with a stale old dressing of “local control” complaints. Icky. (Newark Advocate, 4/28/19)

- But sometimes there’s old news that just begs to be repeated (such as, say, the fact that there is no chaos in Lorain City Schools), because it’s been overlooked (or outright hidden) and someone important might actually realize it’s true. (Elyria Chronicle, 4/27/19)

- In somewhat newer news, there is no chaos in East Cleveland City Schools either. In fact, the new CEO there has gotten quickly and quietly down to work and has some great plans for turning around that district’s longstanding academic malaise. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 4/27/19)

- Finally today, and keeping with our theme, centralized career-tech education is way old news in Toledo City Schools, apparently. A plan put forward five years ago (which doesn’t even seem to have gotten its boots on in that time) to do just that is now dead, and the building originally targeted for it will be scrapped out and sold, according to the same district supe who proposed the plan. The new news is that he is spreading it around instead (career-tech opportunities, that is). I can’t quite tell if he’s talking about the numerous high school academies already coming online, but who cares? The news is apparently always new in Toledo. (Toledo Blade, 4/29/19)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox (in case you want to keep up with the newest of old news by signing up for such a newsletter)? Subscribe by clicking here.

Solving the charter school facilities conundrum

Fordham’s Aaron Churchill recently dug into the many facility challenges charter schools face. He discusses a January report from the Ohio Auditor of State that highlighted some of the policies that force charter schools into less conventional—and sometimes concerning—facility arrangements. Most importantly, Churchill finishes by offering three policy ideas that would better enable charters to obtain suitable spaces at affordable prices.

Lorain charter school hosts Kindergarten STEAM Fest

Horizon Science Academy, a public charter school in Lorain, hosted Lorain’s first ever Kindergarten STEAM Fest this past week. Kindergarteners and their families had the opportunity to participate in sixteen different STEAM experiments, engage in innovative learning, and practice their presentation skills by presenting their projects to judges.

What charters see in Opportunity Zones

CityLab recently published a story discussing the charter school community’s growing interest in Opportunity Zones, which could help thousands of charter schools pay for new facilities or finance renovations (Ohio alone has designated 320 tracts as Opportunity Zones). CityLab references national and Ohio experts and discusses how this method of financing would actually work.

Charters and colleges are redefining success

Bruno V. Manno, the senior advisor for the K-12 Education Program at the Walton Family Foundation, recently wrote about how some charter school networks and postsecondary institutions are changing the economic trajectory of students from low-income backgrounds. He discusses two analyses, including Richard Whitmire’s The B.A. Breakthrough and Opportunity Insights’ mobility report cards, that show how K-12 and postsecondary education “can propel students from low-income backgrounds up the ladder of economic opportunity into the middle class and beyond, keeping the American dream alive.”

Legislative update

This week at the Statehouse is likely the calm before the storm. Neither the House and Senate Education committees nor the Finance committees met. The House has been working on amendments to the budget bill, HB 166. The sub bill for HB 166 is expected next week. The Joint Education Oversight Committee (JEOC) met on Thursday and kicked off a series of hearings in which they’ll look at the various components of Ohio’s school report cards. You can access materials from the meeting here.

- The benevolent, student-centric process of “school absorption” described in this piece is not possible given the way charter and district schools are run in Ohio. But so many questions are unanswered or elided that it’s not possible to really figure out what’s going on from here. Either Toledo City Schools is somehow forcing a successful Spanish-language charter school to close or else the school is closing on its own instead of expanding as it apparently wished to do. Whether it’s one of those things or perhaps something else entirely, the charter school will go away, and the district will launch its first ever Spanish-language program. Either way, it seems to me that Spanish-speaking families in Toledo will have one less educational option next school year. (Toledo Blade, 4/24/19)

- As promised, the Youngstown Academic Distress Commission announced its pick for the next district CEO. Justin Jennings, currently the superintendent of Muskegon Public Schools in Michigan, is supposed to start August 1…pending the outcome of a couple of unrelated issues. You know what I’m talking about. (Youngstown Vindicator, 4/25/19)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox (in case you want to go with the flow and sign up for such a newsletter)? Subscribe by clicking here.

Charter school students deserve every opportunity to learn in facilities built to meet their needs. Sadly, however, many of them attend schools lacking the amenities that parents normally expect—things like playgrounds, gymnasiums, science labs, and cafeterias. Most Ohio charter students, as a 2016 report finds, learn in cramped spaces that are smaller than the state’s recommended guidelines.

Charter schools’ inadequate facilities are the result of deficient policies. A January report released by former Auditor of State Dave Yost highlights the challenges facing charters—and the lengths to which some go to secure facilities. The auditor issued this “public interest report” in response to complaints about the leasing agreements of Ohio charter schools affiliated with the Concept, Imagine, and National Heritage Academy management companies. But before diving into the particulars of these cases, the auditor’s report lays out four facility barriers facing charters:

- Charters don’t have the same levers as school districts to raise money for facilities. Unlike districts, charters cannot ask local taxpayers to support bonds that provide the tens of millions needed for capital projects. Moreover, charters cannot access the state’s major school construction programs that have disbursed billions in state aid over the past two decades.

- Unlike districts, charters can be closed for academic underperformance. The risk of closure due to fiscal stress is also a possibility, as Ohio charters receive significantly less funding than nearby districts. These realities limit access to credit markets because lenders may be unwilling to loan millions to schools that could close before the dollars are repaid.

- Districts are often reluctant to offer unused space to charters. As the auditor notes, Cincinnati Public Schools used to put deed restrictions on disposed properties that prohibited charters from using them. The Ohio Supreme Court stopped that practice, but stories from Cleveland and Columbus suggest that districts still sometimes take steps to deny facilities to charters.

- The state provides austere charter facility support. The auditor’s report notes the $200 per-pupil allowance for charter facilities—which covers just a fraction of maintenance and leasing costs—and a modest $25 million grant that has supported renovations in a dozen or so schools. Yet beyond this there are no other state aid programs that support charter facility needs.

Taken together, these policies force charters into less conventional facility arrangements. The figure below shows that the vast majority of Ohio charters rent space, which the report attributes to difficulties in obtaining financing or grants. Less than 20 percent of charters have cobbled together the funds needed to purchase a facility. Some of these fortunate schools have already become pillars in their community, and with a building of their own, their prospects for the future are bright.

Figure 1: Charter school facility arrangements

While there is nothing inherently wrong with leasing space, the auditor’s report also describes the questionable leases of nine Ohio charter schools. These schools entered into unfavorable leases with real-estate firms tied to their management companies. As one of the few (if not only) suppliers of a viable facility, the management company held tremendous leverage over the school boards—and won leasing terms reflecting that power. The charter boards couldn’t easily walk away from the management company offer—no matter how bad the terms—and pursue other avenues.

This situation raises several concerns. First, the expensive leases—in some cases, roughly double the market rate—eat into the resources available for classroom instruction. Second, the high rents raise worries that taxpayer money is inappropriately benefitting real estate firms instead of schools. Third, leases such as these weaken charter school boards’ ability to sever ties with poor-performing management companies, as doing so could result in the school losing its building.

Fortunately, there are ways to fix this. Ohio has already undertaken serious reforms aimed at curbing these types of abuses, and the auditor offers additional suggestions—most notably, subjecting leases to competitive bidding.[1] Yet as the auditor recognizes, regulation alone can’t solve charters’ broader facility challenges. To this end, Ohio should pursue policies that would better enable charters to obtain suitable spaces at affordable prices. The most critical include the following three.

Strengthen state supports. Because charter schools lack access to local taxpayer support, the state needs to step up and support charter facilities. With only a meager $200 per-pupil facility reimbursement, charters have to use operational dollars—already stretched thin by inequitable funding—to pay for things like maintenance, utilities, and rent. Charters shouldn’t be forced to dip into instructional dollars just to make ends meet, and Ohio should increase the amount of dedicated facility funds to one that more closely matches the cost of maintaining a building. At the same time, legislators should also re-appropriate funds for the Community Schools Classroom Grant, so that more charters can undertake capital improvement projects.

Create a credit-enhancement program. To improve charters’ access to credit, Ohio should implement a “moral obligation” program. Already adopted by Colorado, Idaho, and Utah, this program would allow qualifying charters to use the state’s superior credit rating when seeking debt financing for capital projects, enabling them to secure funds at lower interest rates and save thousands of dollars over the life of a loan. Should a charter default, the state would pledge—and this is the moral obligation—to repay lenders. (Participating Colorado charters also cover some of the costs by paying into a reserve fund.) Ohio already has a loan guarantee program on the books for charters, but there is no evidence of use, nor any money appropriated to support it. To jump-start state backing for facility purchases and capital improvements, legislators should revive this law by appropriating reserve funds, increasing the amount of liability that the state can back, and allowing qualifying charters to substitute the state’s credit ratings when seeking loans.

Encourage use of underutilized buildings. Mothballed schools that have already been paid for by taxpayers are an obvious solution to charter facility woes. While Ohio does have a “right of first refusal” law, policymakers should go further to ensure districts actually make space available to charters. To do this, Ohio could take a cue from Indiana and publish a list of unused buildings that charters can potentially buy or lease. State lawmakers could also consider California’s approach, which requires districts to make underutilized space available to charters. This could encourage co-location in half-empty buildings, which can benefit not only charter students, but also pupils attending district schools. Given demand for facility space, there is no reason that any publicly financed building should go vacant or underutilized.

***

Cramped classrooms and dubious leases are symptoms of Ohio’s inadequate charter facility policies. To ensure that all charter school students have the opportunity to learn in spaces built for learning, legislators should work to cure the underlying disease.

[1] In fall 2015, legislators enacted sweeping regulatory charter reforms whose effects may not have shown up in the auditor’s analysis of 2015–16 leasing data. Among other things, they include a provision that now requires an independent real estate agent to declare a lease “commercially reasonable” before a school and management company sign an agreement.

The General Assembly’s Joint Education Oversight Committee has begun a series of hearings looking at all of the various components of Ohio’s school report cards. One component will be examined per meeting. Today, JEOC members reviewed testimony on the achievement component. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy Chad Aldis provided the following written testimony.

Thank you, Chair Cupp, Ranking Member Fedor and the Joint Education Oversight Committee members for giving me the opportunity today to provide written testimony on the Achievement component of Ohio’s school report cards.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

As many of you know, Fordham is a staunch supporter of rigorous, transparent school report cards. We believe that families and taxpayers deserve an opportunity to review the progress of their local schools. Over the past two decades, Ohio has implemented a robust report card that now includes key measures of student achievement and growth, along with indicators of college and career readiness. This multi-faceted approach offers a wealth of data but as the state has implemented new measures, the report card has become increasingly complex. While my comments below focus on the Achievement component, they should be viewed in the context of our broader thinking about how to improve school report cards which can be found in our December 2017 paper Back to the Basics. [1]

Parents, educators, and researchers have long understood that achievement is linked to adult success. Students who excel academically are more likely to attend our best colleges and universities, obtain the most rewarding jobs, exercise their civic duties, and enjoy the benefits of lifelong learning. This is why assessing and reporting achievement in core academic subjects remains a central responsibility of our education accountability systems.

Since their earliest iterations, Ohio’s report cards have focused heavily on achievement. Proficiency rates—in layperson’s terms, the percent of students “passing” state exams—are perhaps the most well-known indicator of achievement. Today, proficiency rates on various state exams are included in a report card measure known as Indicators Met. Furthermore, Ohio has long used the Performance Index, a measure that awards additional credit to schools when students achieve at higher levels. The table below depicts how the index works, with the weights and some illustrative data shown. The “% Students” column is what varies from school to school and is determined by the number of students achieving each level on the state assessment.

Districts and schools receive separate letter grades for proficiency rates (via Indicators Met) and the Performance Index. Moreover, the data from these two subcomponents feed into the larger Achievement component rating through a system that places 75 percent weight on Performance Index and 25 percent on Indicators Met. In total, districts and schools receive three letter grades (Overall Achievement, Indicators Met, and Performance Index) based on the achievement of students on state exams.

Ohio should assign a clear rating based on student achievement. But the dual Performance Index and Indicators Met ratings—along with the composite Achievement grade—communicate largely redundant information about how students fare against state standards. As a result, schools tend to receive similar grades on these metrics and low (or high) grades can “pile up” on schools. For instance, the Dayton school district—serving primarily low-income students—received F-F-F ratings on the Performance Index, Indicators Met, and Achievement on its 2017-18 report cards. The multiple ratings that signal similar things about student achievement could be seen as unnecessarily severe for high-poverty districts and schools that tend to struggle on “status” measures.

There are tradeoffs to consider when comparing the use of the Performance Index versus proficiency rates. In an accountability setting, the Performance Index encourages schools to widen their attention to all students, as it offers them additional credit when students reach higher levels. Meanwhile, relying on proficiency rates creates incentives for schools to focus narrowly on students just below the proficiency bar. That being said, proficiency rates have a straightforward interpretation, while the Performance Index is less intuitive. Although proficiency rates are critical to report, many scholars and educators now believe that an index represents a superior approach to accountability, as it encourages schools to serve students along the entire achievement spectrum.[2]

With regard to the Achievement component, we recommend eliminating Indicators Met. Instead, a single Achievement component rating based on Performance Index scores would best convey how all students in a school perform against state academic standards. Proficiency rates, however, should continue to be calculated and reported for informational purposes. ODE should report proficiency rates by grade and subject (and by subgroup) as supporting information on school report cards and in its various data systems. Schools, however, should receive their Achievement rating based solely on their Performance Index scores.

Student achievement remains a central feature of school report cards; families and citizens deserve clear indicators of how students currently perform against state academic standards. With a few modifications, Ohio could create a clearer portrayal of achievement, while also incentivizing schools to lift the achievement of all students—not only those around the proficiency bar.

Thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony and please feel free to contact me with any further questions.

[1] https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/research/back-basics-plan-simplify-and-balance-ohios-school-report-cards.

[2] See for example, Morgan Polikoff, “A letter to the U.S. Department of Education (final signatory list)” (July 22, 2016): https://morganpolikoff.com/2016/07/12/a-letter-to-the-u-s-department-of-education/.

It’s one of the great conundrums of American public education: Even when calculated in constant dollars, and even after the Great Recession, the U.S. is spending dramatically more per pupil than in decades past, yet teacher salaries have barely kept pace with inflation. This raises several key questions: Where is the money going, if not into salaries? And how much could we pay teachers if we prioritized higher salaries instead?

To be clear, I don’t have all the answers. But I do have a fresh look at the data.

Introducing the salary-to-spending ratio

To shed some light on this issue, I decided to compare average teacher salaries to average per-pupil spending—by state, and over time, all in inflation-adjusted dollars.

This is a twist on just looking at average teacher salaries, which can be instructive if you want to understand where teachers have the best argument that they are underpaid (especially if the numbers are adjusted for cost of living differences). That’s important information, especially in this season of teacher strikes and protests, but I was curious about a different question: Which states, if any, have prioritized higher teacher pay over other possible uses for their education funds? To put it another way, as spending rose in recent decades, which states have chosen to put the additional dollars into higher salaries instead of other options, such as smaller classes, employee healthcare and retiree benefits, or additional staff, especially?

That’s because, as my colleague Checker Finn has long argued, if we as a country had chosen better teachers (via higher salaries) over more teachers (via smaller class sizes and more personnel), we might have gotten stronger results.

Keep in mind that changes in average teacher salaries can reflect both changes in teacher pay scales and in teacher “composition.” For example, if the teaching force becomes significantly younger over time, average teacher salaries will drop, even if the pay scale stays the same.

So let’s look at the data, first for the United States as a whole. Again, to keep things simple, we’ll compare the average teacher salary for a given school year to average per-pupil spending, and call it the “salary to spending ratio.” Here’s what that’s looked like from 1990 forward:

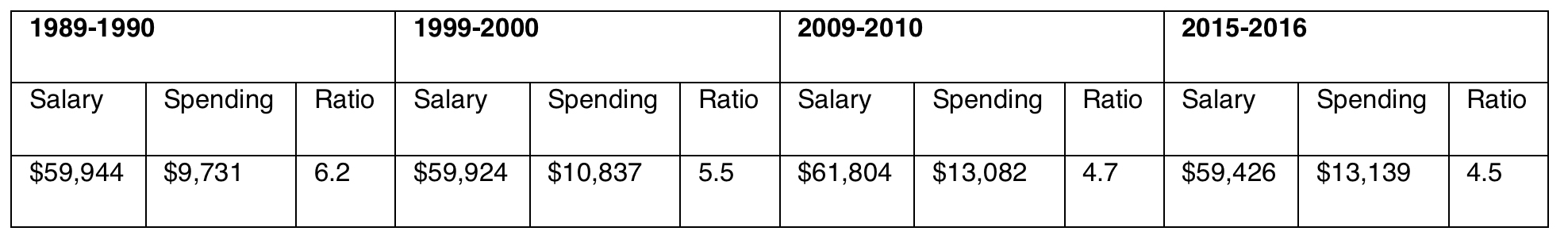

Table 1: U.S. average teacher salaries, average per-pupil expenditures, and

salary to spending ratio, 1990–2016 (inflation-adjusted)

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics 2019, tables 211.60 and 236.70.

The average teacher salary has been remarkably consistent over this period, even though spending has increased by 35 percent, and that has dropped the salary-to-spending ratio from 6.2 in 1990 to 4.5 in 2016. If salaries had risen at the same rate as spending, the average teacher salary by 2016 would have been more than $80,000 per year, versus a bit less than $60,000.

Salary-to-spending ratios: State-by-state differences

So the U.S. as a whole now has a salary-to-spending ratio of 4.5. Are there any differences at the state level? That might suggest that some states are making higher teacher salaries a priority. There are indeed differences. Here’s how it looks for 2015–2016.

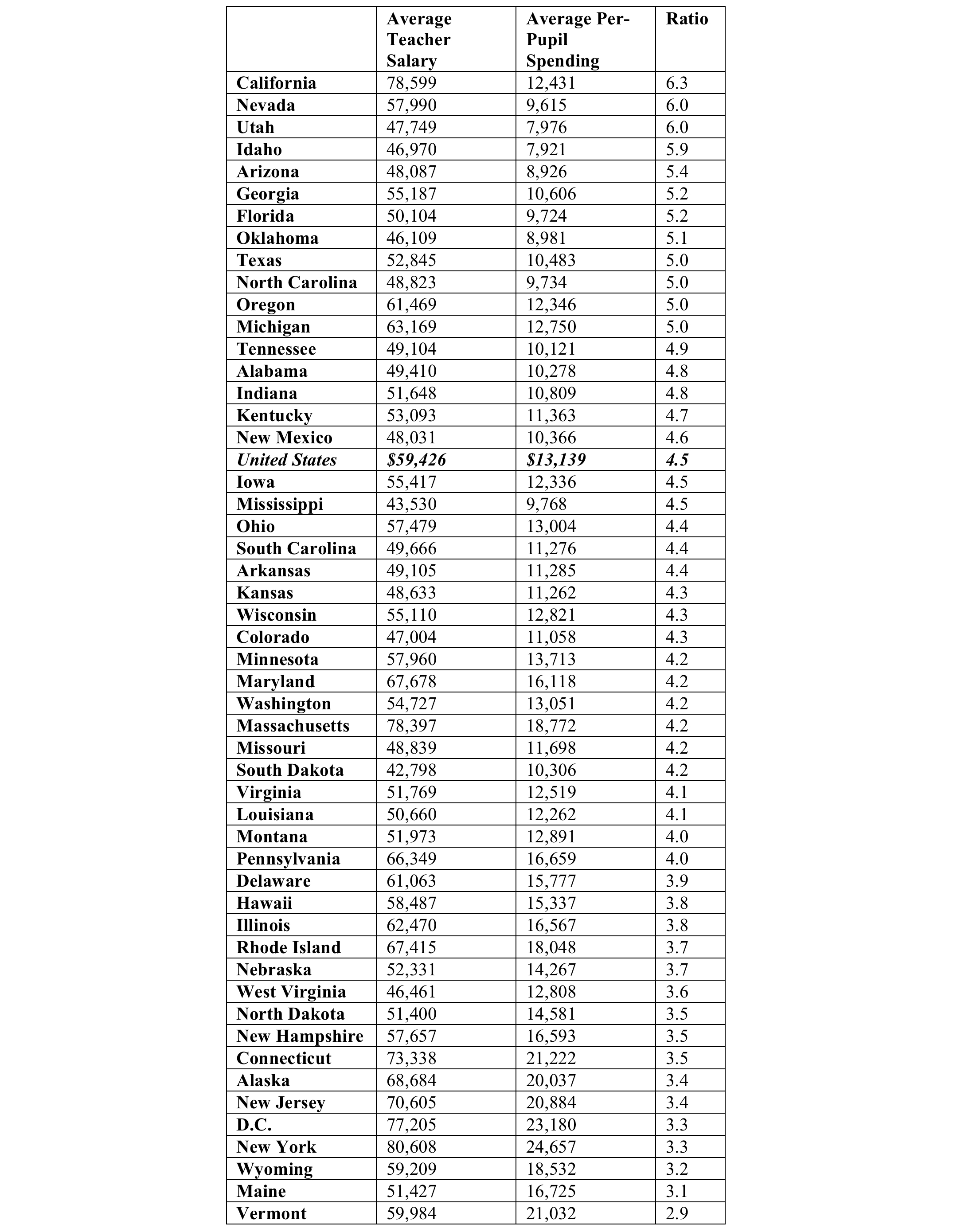

Table 2: Average teacher salaries, average per-pupil expenditures, and

salary to spending ratios, 2015–16

It’s hard to know what exactly to make of these data, but a few patterns do jump out. First, many fast-growing, low-spending states, such as Idaho, Arizona, and Georgia, appear to put more of their scarce dollars into teacher salaries. California is not exactly a low-spending state, yet it’s at the top of the list too, presumably because its high cost of living means it needs to pay more to have any chance at recruiting quality teachers.

Many high-spending states, on the other hand, appear to allocate their additional dollars into more staff, or other items, rather than higher teacher salaries. Maybe that’s understandable in low-cost-of-living states, but it sure seems that expensive ones like New York, Rhode Island, and Connecticut should be putting even more of their dollars into higher salaries. If New York’s salary-to-spending ratio matched California’s, for example, it could be paying teachers an average of about $155,000 a year, instead of the actual average of about $80,000.

I also wonder about special education. Many of the states at or near the top of the list, including California, have famously low rates of special education identification, while many toward the bottom, such as New York, have high rates. Is that because some states truly have more kids with disabilities? Or are lower-spending states finding ways to be stingier about who gets identified, thus avoiding the need to hire lots of additional support staff?

State-by-state salary-to-spending ratios over time

Let’s take one more cut at the data, and see if any interesting patterns emerge at the state level over the past quarter century.

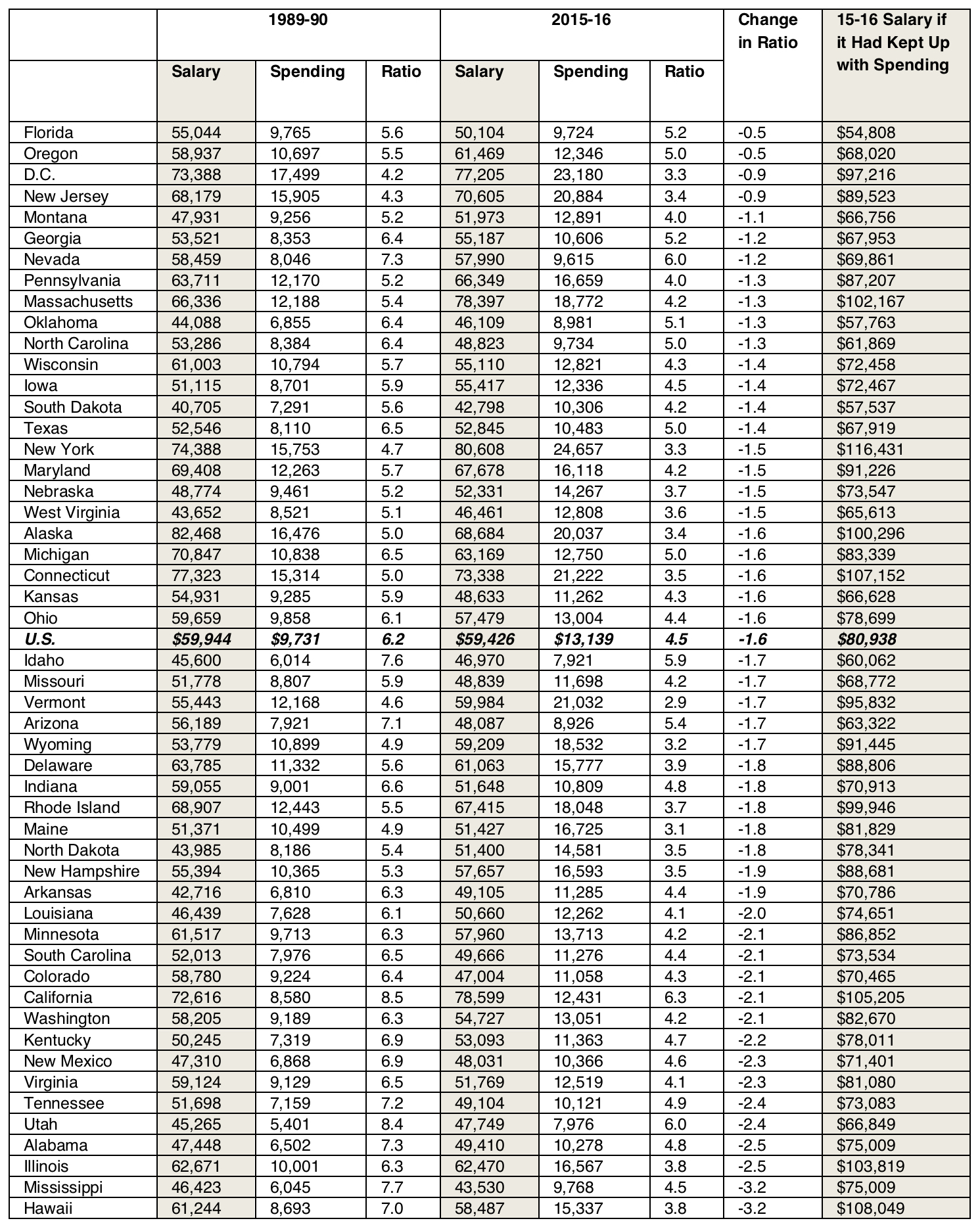

Table 3: Average teacher salaries, average per-pupil expenditures, and

salary to spending ratios, by state, 1990–2016 (inflation-adjusted)

Now we have a different way at looking at the issue. It’s notable that the salary-to-spending index decreased in every single state, showing that salaries faced competition from other expenses everywhere. Throughout the economy, health care expenses have eaten into pay, so that’s one likely culprit.

But some states held the line on salaries much more than others.

Florida comes out on the top of this list, though it’s a peculiar case, given that inflation-adjusted salaries there actually declined over this period. But given how flat spending has been in the Sunshine State, it could have been worse had leaders not kept their scarce dollars from going elsewhere.

Better examples are Oregon, D.C., and New Jersey, all of which increased their spending over time, and found a way to drive at least some of the additional dollars into salaries.

At the bottom of the list are states that could have plowed their big spending increases into higher teacher salaries but didn’t. Illinois may be the poster child, with per-pupil expenditures rising from about $10,000 in 1990 to more than $16,500 by 2016. Yet teacher salaries barely budged. If they had instead kept pace with spending (which is what the last column shows), they would have risen from about $63,000 a year to over $100,000.

***

To be sure, this analysis is just scratching the surface. Additional analyses could go much deeper, looking at changes in school expenditures over time, and examining the impact of smaller class sizes; the hiring of additional staff, like teacher coaches; the rising costs of health insurance and pension payments; and other categories of spending, like administration. Breaking all of this out by state would be instructive, as it would help policymakers in a given jurisdiction understand the choices their own schools are making, and start to investigate why that might be.

In the meantime, when someone complains that teacher salaries are not high enough, you should agree with them. But next explain that the problem in most places isn’t overall education spending—it’s how we choose to invest our dollars. And you can really rock their world by saying that schools in Nevada, Utah, and Idaho are prioritizing teacher pay much more so than their counterparts in Vermont, Maine, and New York.

I used to give a talk about teaching reading comprehension to struggling students, mocking some of the dumb and deleterious techniques I was taught in my teacher training and professional development, and arguing that none of it works as well as ensuring kids have a knowledge-rich core curriculum. When I would give this speech to education reform groups, I’d end with a deliberately puckish twist, pointing out that the overreliance on reading comprehension skill and strategies I’d just called out was the default mode of instruction in many of the high-flying charter schools so beloved by reformers. And how bright, shiny Teach For America corps members were no less likely to use these ineffective techniques as the tired and tenured unionized teachers reformers seemed so eager to blame and replace.

I surely didn’t endear myself to my fellow reformers by noting that, while our movement seemed oddly indifferent to how kids were being taught to read, there was at least one organization that understood the value of a strong, knowledge-rich curriculum: the American Federation of Teachers. Going back to Al Shanker’s time, the AFT has been stalwart in its support of E.D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge approach to literacy, through the high-profile advocacy of its excellent quarterly, The American Educator, which reaches nearly a million teachers, and has regularly published work by Hirsch, Dan Willingham, Jeanne Chall, Marilyn Jager Adams, and many other leading experts.

Unlike most of my ed reform brethren, I’m not a union basher. I’ve never fully bought into the common complaints that unions are the sum and substance of all that ails education. Mind you, I wouldn’t suggest they’re on the side of the angels (all my chapter leader ever did for me when I was teaching in the Bronx was try to get me fired). But I’m more open than most to seeing unions as possible partners rather than purely a problem.

I offer this all as a preamble before expressing my disappointment with AFT President Randi Weingarten’s speech on “The Freedom to Teach” delivered last week at the National Press Club, in which she lamented the nation’s “disinvestment” in education and the “deprofessionalization” of teaching.

Weingarten delivered her speech from a position of considerable strength. Over the past sixteen months, striking teachers have met with surprisingly consistent sympathy in their states and communities. Ed reform, meanwhile, is rocking back on its heels. So much so that progressives seem determined to make past support for charter schools a dealbreaker for the Democrats’ 2020 presidential candidates, no less a mark of shame than groping underlings or being photographed in blackface. But rather than leverage the moment to lead, Weingarten’s remarks seemed ripped from union boilerplate circa 2002, the standard litany of complaints about funding and working conditions, too much of it playing fast and loose with the facts. While it may be true, for example, that teachers are leaving their classrooms “at the highest rate on record,” teacher churn is a standard feature of tight labor markets, and at current levels still only about one-third of the rate for American workers overall. Comparatively speaking, teaching is still a pretty good gig.

In surveying the diminished state of American education, Weingarten had nothing to say about charter schools or choice, which is unsurprising from a labor leader. But she asked why we aren’t making neighborhood schools “centers of their communities” just weeks after New York City’s ended just such a program after four years, $800 million spent, and nearly nothing to show for it. Weingarten noted that parents don’t want their kids to become teachers anymore and lamented how enrollment in teacher preparation programs is plummeting. “More than 100,000 classrooms across the country have an instructor who is not credentialed,” she complained. “How many operating rooms do you think are staffed by people without the necessary qualifications? Or airplane cockpits? We should be strengthening teacher preparation programs, not weakening teacher licensure requirements, leaving new teachers less and less prepared.” That was all she had to say about teacher preparation. That’s disappointing and misses the mark badly. Teacher preparation programs have simply not done their part to produce the skilled teacher workforce worthy of the respect and autonomy Weingarten thinks should be their due.

Comparing teachers to surgeons and airline pilots elides the obvious and enormous differences in selectivity and training for those jobs. There are about 3.6 million teachers in America. The closest occupations in raw numbers to teachers are food service workers, including fast food, and cashiers. The only larger occupation is retail salespersons. If America employed 3.6 million surgeons and airline pilots and trained them as casually as teachers, we would have a very different relationship to the healthcare and airline industries. No other workforce of a comparable size is regarded as a profession; no other unionized workforce of a comparable size enjoys the level of professional autonomy that Weingarten thinks teachers deserve. In citing only teacher “credentials” and “qualifications,” she missed an opportunity to demand that teacher preparation programs do a better job preparing and elevating her future members.

The past year has seen an unusual spike in interest in how teachers are trained (or not) to teach reading, and a strong outpouring of teacher anger at their lack of preparation. Many of these teachers (probably most) are union members. For a significant subset of them, the frustration and demoralization that Weingarten cited is only worsened by their lack of preparation. Among her prescriptions to “change the culture” of education is “ensuring teachers have real voice and agency befitting their profession.” One of the loudest and clearest messages emerging from that real voice is that teachers are being set up to fail by those charged with preparing them. Weingarten missed an opportunity to lead and be vocal about this.

Make no mistake, teachers are more sinned against than sinners in the state of teacher prep. The AFT could do a world of good for its members—and for children—by throwing its considerable weight behind an effort to demand ed schools be held accountable for graduating teachers prepared for success, armed with the knowledge and expertise to be granted full professional status and esteem. Instead, Weingarten harped predictably on “prepackaged corporate curriculum” and attempts to “standardize teaching to conform with the standardized assessments.” Such efforts are not only “denying teachers’ creativity and expertise, but assuming their incompetence.” But the teachers who are raising their voice in anger don’t seem upset at the assumption they are incompetent. They are angry they have been rendered incompetent by inadequate training and poor curriculum and support. No organization is better positioned to address this than America’s teachers unions, and particularly—with its longstanding advocacy for effective curriculum and pedagogy—the AFT.

The “freedom to teach” Weingarten is demanding presupposes that left to their own devices, teachers would perform capably, and better than under the thumb of regulators and busybodies. This is a winning argument for those of us prone to see overregulation as a drag on performance in any sector. Weingarten’s freedom to teach assumes, contrary to all available evidence, that teachers know what to do and need only to be freed to do it. Yet this is precisely the same mistake made by a generation of ed reform accountability hawks, who assumed that the right incentives would drive schools and teachers to better practices. It has proven disappointing as a reform theory of change. Nothing in Weingarten’s stemwinder of a speech offers any reason to think outcomes will be any different if we do it her way instead.