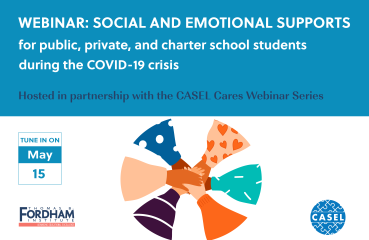

What AP teachers taught us about learning continuity during coronavirus

The sudden shift to remote learning this spring demanded that schools innovate and adapt with incredible speed. The entire education world is trying to serve millions of suddenly home-bound students, and there’s simply no precedent for a challenge on that scale.