Editor’s note: This is an edition of “Advance,” a newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on the Fordham Institute website and the newsletter’s Substack.

We have ample evidence that a number of education programs targeted at advanced students significantly improve their learning outcomes. Because of that, high-quality gifted education—or what would be better labeled “advanced education”—has two primary benefits. One, it helps maximize the potential of participating students, which is something every child deserves. And two, in better developing the talent of these advanced students, it supports America’s economic, scientific, and technological prowess in an increasingly competitive global market. It’s therefore important that more school leaders adopt these policies and implement them well.

As Jonathan Plucker, Julian C. Stanley Professor of Talent Development at Johns Hopkins University, explained in a Fordham Institute article a couple years ago, the two interventions with the most robust evidence behind them are acceleration and ability grouping—with enrichment, such as summer and residential programs, having generally positive results, too.

Acceleration is “an academic intervention that moves students through an educational program at a rate faster or at an age that is younger than typical,” reports the highly-respected Belin-Blank Center at the University of Iowa. It comes in at least twenty forms, with the most common being whole grade skipping and receiving higher-level instruction in a single subject. It is “one of the most-studied intervention strategies in all of education, with overwhelming evidence of positive effects on student achievement,” writes Plucker. One study that looked at approximately 100 years of research on the intervention’s impact on K–12 academic achievement, for example, found three meta-analyses showing that “accelerated students significantly outperformed their nonaccelerated same-age peers,” and three others showing that “acceleration appeared to have a positive, moderate, and statistically significant impact on students’ academic achievement.” The Belin-Blank Center also offers an excellent and thorough summary of the evidence related to acceleration.

Numerous high-quality studies have also found that flexible ability grouping—arranging students by academic achievement in the same or separate classrooms—is a net positive for advanced students and isn’t detrimental to their peers. The aforementioned review of a century of research, for example, looked at thirteen meta-analyses of ability grouping, and three models boosted outcomes: within-class grouping, cross-grade subject grouping, and special grouping for the gifted. Moreover, there seemed to be little downside for medium- and low-achieving students, and often upside. Research on curriculum models can also be placed under the ability-grouping umbrella, and “those studies suggest that pre-differentiated, prescriptive curricula lead to significant growth in advanced learning,” writes Plucker.

Because these interventions work, we ought to use them. Why? Because doing so benefits both the individual students and the country in general. Each and every child deserves an education that meets their needs and enhances their futures, and advanced students are no different. They have their own legitimate claim on our conscience, our sense of fairness, our policy priorities, and our education budgets.

What’s more, many of them also face such challenges as disability, poverty, ill-educated parents, non-English-speaking homes, and tough neighborhoods. Many also attend schools awash in low achievement, places where all the incentives and pressures on teachers and administrators are to equip weak pupils with basic skills in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Such schools understandably invest their resources in boosting lower achievers. They’re also most apt to judge teachers by their success in doing that and least apt to have much to spare—energy, time, incentive, or money—for students already above the proficiency bar.

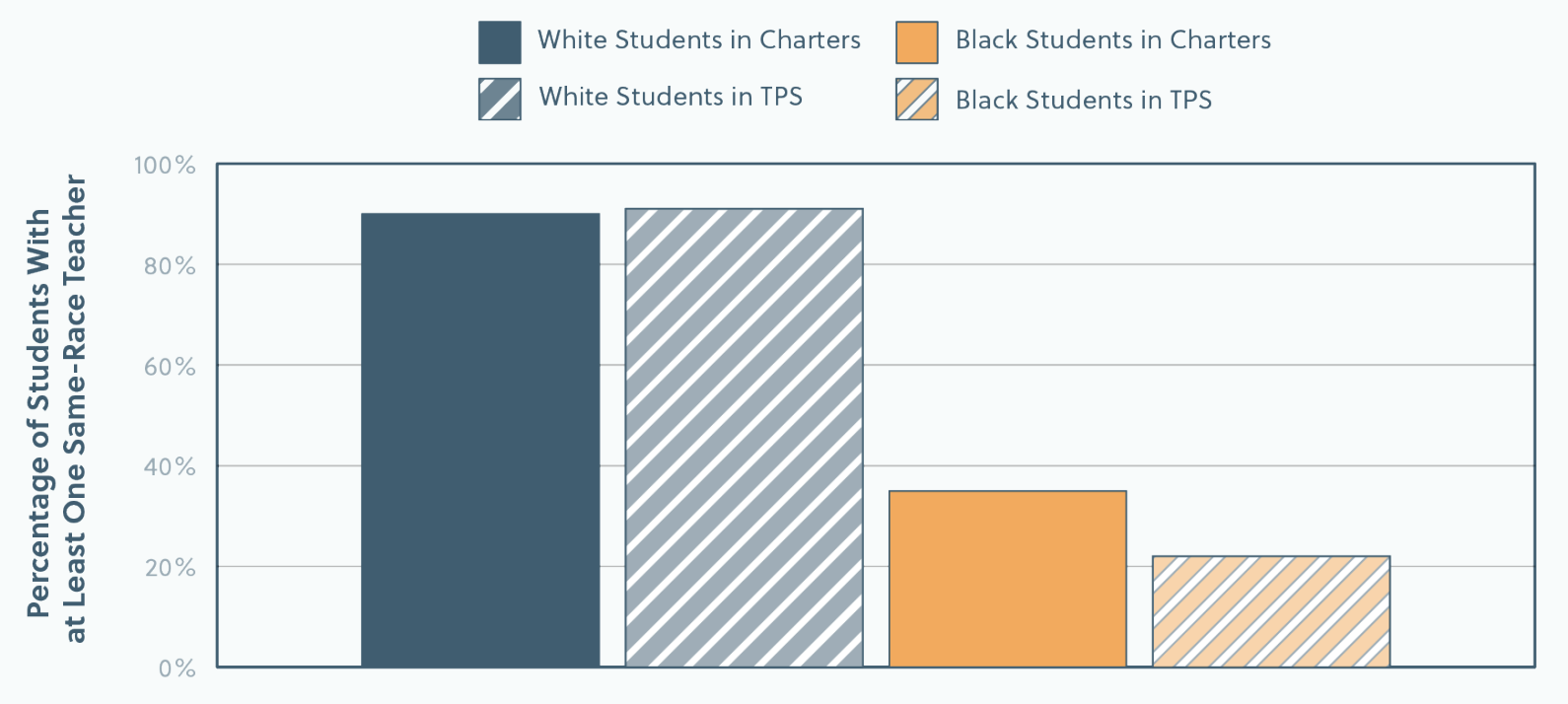

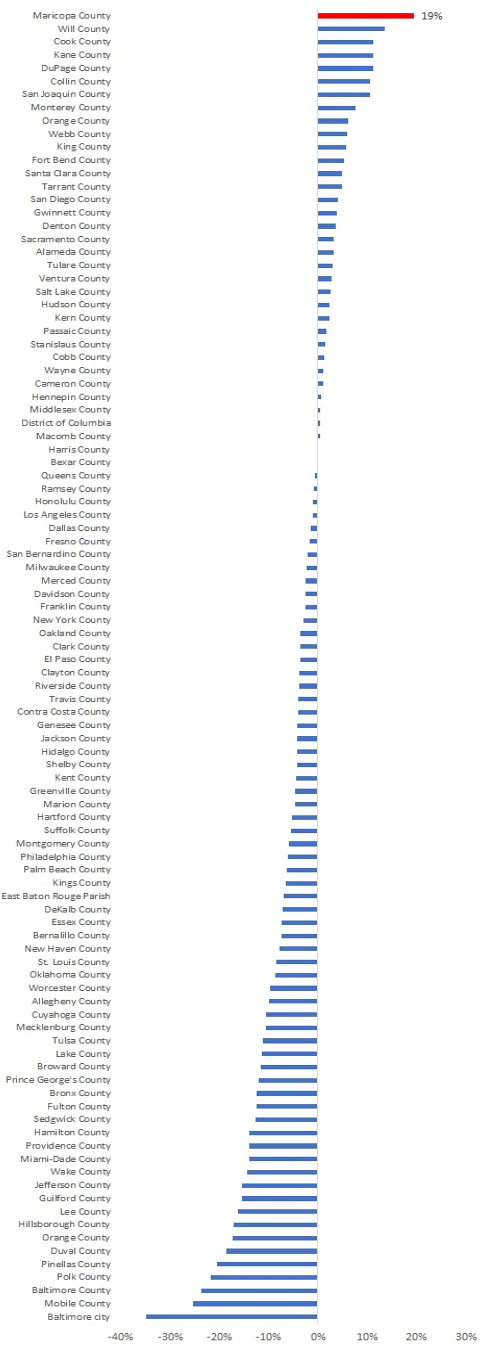

It’s advanced students from these disadvantaged and oft-marginalized backgrounds who most need these programs—but they’re also the least likely to have access to them. A Fordham study in 2018 called Is There A Gifted Gap? found, for example, that White students constitute 47.9 percent of the student population but 55.2 percent of those enrolled in advanced learning programs, while the comparable figures for Black students are 15.0 and 10.0 percent, and for Hispanic students, 27.6 and 20.8 percent. And these forces contribute to widening gaps as they progress through grades. Those latter student groups are 49 and 23 percent less likely, respectively, to participate in Advanced Placement than their peers, and 62 percent and 51 percent less likely, respectively, to take part in International Baccalaureate courses when attending a school that offers them. Better-designed programming for advanced students in more places, implemented well, would help change that.

The second big reason for more and better advanced education interventions is that the country needs these children to be highly educated to ensure its long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation. They’re the young people most apt to become tomorrow’s leaders, scientists, and inventors, and to solve our current and future critical challenges. The same point was framed in different words in the 1993 federal report titled National Excellence: A Case for Developing America’s Talent: “In order to make economic strides,” the authors wrote, “America must rely upon many of its top-performing students to provide leadership—in mathematics, science, writing, politics, dance, art, business, history, health, and other human pursuits.”

But the U.S. and its schools have long underperformed many of our competitor countries, according to two respected international metrics: the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), in which dozens of countries participate. PISA tests fifteen-year-olds in math, science, and reading, and organizes its scores into seven levels, from 0 to 6, with high scorers generally being those who reach level 5 or 6. TIMMS assesses fourth and eighth graders in math and science and splits its scores into five levels, with a high achiever judged as one who reaches at least 625 on the relevant scales.

Using these cutoffs on the most recent math assessments—2018 for PISA and 2019 for TIMSS—illustrates the magnitude of the problem.

In the TIMSS results, the U.S. ranks eleventh in grade four and eighth in grade eight. In both, America landed behind Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, and Russia. Worse, the top-performing countries have two, three, and in the case of Singapore, almost four times the proportion of advanced students as does the U.S. The only silver lining is that many of these countries are small. America’s vast scale means that we have a decently large number of high achievers in raw numbers.

PISA paints an even worse picture for high-achieving high school students in the U.S., mirroring our dismal NAEP results for twelfth-graders. Rankings include all members of the OECD that took the assessment, plus Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and a quartet of Chinese cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang). That’s a total of forty jurisdictions. The United States comes in thirty-fourth, behind all participants in Asia and every participant in Europe except Spain, Turkey, and Greece.

The problem, of course, is not that the United States lacks smart children. It’s that such kids aren’t getting the education they need to realize their potential, allowing other countries like China to forge ahead. Using other international test data, for example, economists Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann estimate that a “10 percentage point increase in the share of top-performing students” within a country “is associated with 1.3 percentage points higher annual growth” of that country’s economy, as measured in per-capita GDP. Which is to say, if the U.S. propelled more of its young people into the ranks of high achievers, it would be markedly more prosperous—with faster growth, higher employment, better wages, and all that comes with these. As the United States faces ever-steepening economic competition from China and elsewhere—not to mention mounting challenges to our national security and wellbeing, including climate change, intergenerational poverty, growing partisanship, and much more—the stakes are high and rising.

The good news is that we have evidence-based methods for reversing these trends: acceleration, ability grouping, and enrichment programs. When well-designed and carefully implemented, these interventions have long proven to boost the achievement of advanced students. This in turn gives these young people the education they deserve, and helps ensure American competitiveness, prosperity, and security for future generations. Sadly, far too many schools don’t offer these services or don’t implement them well, and there’s a misguided push to eliminate them in more places. Instead, more districts should adopt them—the sooner the better.

—

QUOTE OF NOTE

“A group of U.S. children could be set up for failure, despite the fact that they have a notable academic advantage over their peers. Gifted children fall victim to a belief shared by parents, educators, and legislators alike that they ‘will be fine on their own.’”

“When the ‘gifted’ kids aren’t all right,” Deseret News, Addison Whitmer, November 22, 2022

—

THREE STUDIES TO STUDY

“Who Is Considered Gifted From a Teacher’s Perspective? A Representative Large-Scale Study,” by Jessika Golle, Trudie Schils, Lex Borghans, and Norman Rose, Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 67, Issue 1, 2023

“Teachers play important roles in identifying and promoting gifted students. An open question is: Which student characteristics do teachers use to evaluate whether a student is gifted or not? We used data from a representative sample of Dutch primary school teachers (N = 1,304) who were asked whether or not they thought the students (N = 26,720) in their class were gifted. We investigated students’ cognitive and noncognitive attributes as well as demographic factors that might be relevant for this judgment. In sum, the findings revealed that teachers considered students to be gifted when, in comparison with their peers, students were superior in cognitive domains, especially with respect to academic achievement, scored higher on openness to experience and lower on agreeableness, were male, were younger, and came from families with higher parental education.”

“Promises, Pitfalls, and Tradeoffs in Identifying Gifted Learners: Evidence from a Curricular Experiment,” by Angel H. Harris, Darryl V. Hill, and Matthew A. Lenard, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, July 2022

“Disparities in gifted representation across demographic subgroups represents a large and persistent challenge in U.S. public schools. In this paper, we measure the impacts of a school-wide curricular intervention designed to address such disparities. We implemented Nurturing for a Bright Tomorrow (NBT) as a cluster randomized trial across elementary schools with the low gifted identification rates in one of the nation’s largest school systems. NBT did not boost formal gifted identification or math achievement in the early elementary grades. It did increase reading achievement in select cohorts and broadly improved performance on a gifted identification measure that assesses nonverbal abilities distinct from those captured by more commonly used screeners. These impacts were driven by Hispanic and female students. Results suggest that policymakers consider a more diverse battery of qualifying exams to narrow disparity gaps in gifted representation and carefully weigh tradeoffs between universal interventions like NBT and more targeted approaches.”

“The Experience of Parenting Gifted Children: A Thematic Analysis of Interviews With Parents of Elementary-Age Children,” by Jodi L. Peebles, Sal Mendaglio, and Michelle McCowan, Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 67, Issue 1, 2023

“This qualitative study aimed to delve deeply into the phenomenon by interviewing parents of elementary-age gifted children. We conducted 12 interviews with parents whose children attended gifted schools. The interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify key themes related to the experience of parenting gifted children. Themes identified included the parents’ description of a “child-driven” approach to parenting, experiencing social isolation due to a lack of understanding, and physical and emotional feelings of exhaustion. The findings are particularly important for parents of gifted children, and other professionals who would benefit from a better understanding of the day-to-day experience of raising gifted children.”

—

WRITING WORTH READING

“Does growth mindset matter? The debate heats up,” Hechinger Report, Jill Barshay, December 5, 2022

“From a formerly gifted and talented kid, now burnt-out adult: Slow down and take care of yourself,” The Flat Hat, Vivian Hoang, December 5, 2022

“Teens embrace AP class featuring Black history, a subject under attack,” Washington Post, Sydney Trent, December 2, 2022

“NYC’s ‘gifted and talented’ application timeline moves up,” Chalkbeat, Michael Elsen-Rooney, November 30, 2022

“Should your child take AP or IB classes? It could save them thousands in tuition.” Green Bay Press-Gazette, Danielle DuClos, November 29, 2022

“Schools for gifted students: What to know,” U.S. News, Andrew Warner, November 29, 2022

“Michigan to start notifying parents of AP eligibility,” News-Herald, Matthew Fahr, November 24, 2022

“When the ‘gifted’ kids aren’t all right,” Deseret News, Addison Whitmer, November 22, 2022

“$1.5 million NSF award will power scholarships and support for high-achieving, low-income engineering students,” Temple Now, Sarah Frasca, November 18, 2022

“We need to rethink gifted and talented education in NC,” The Daily Tar Heel, Georgia Roda-Moorhead, November 15, 2022