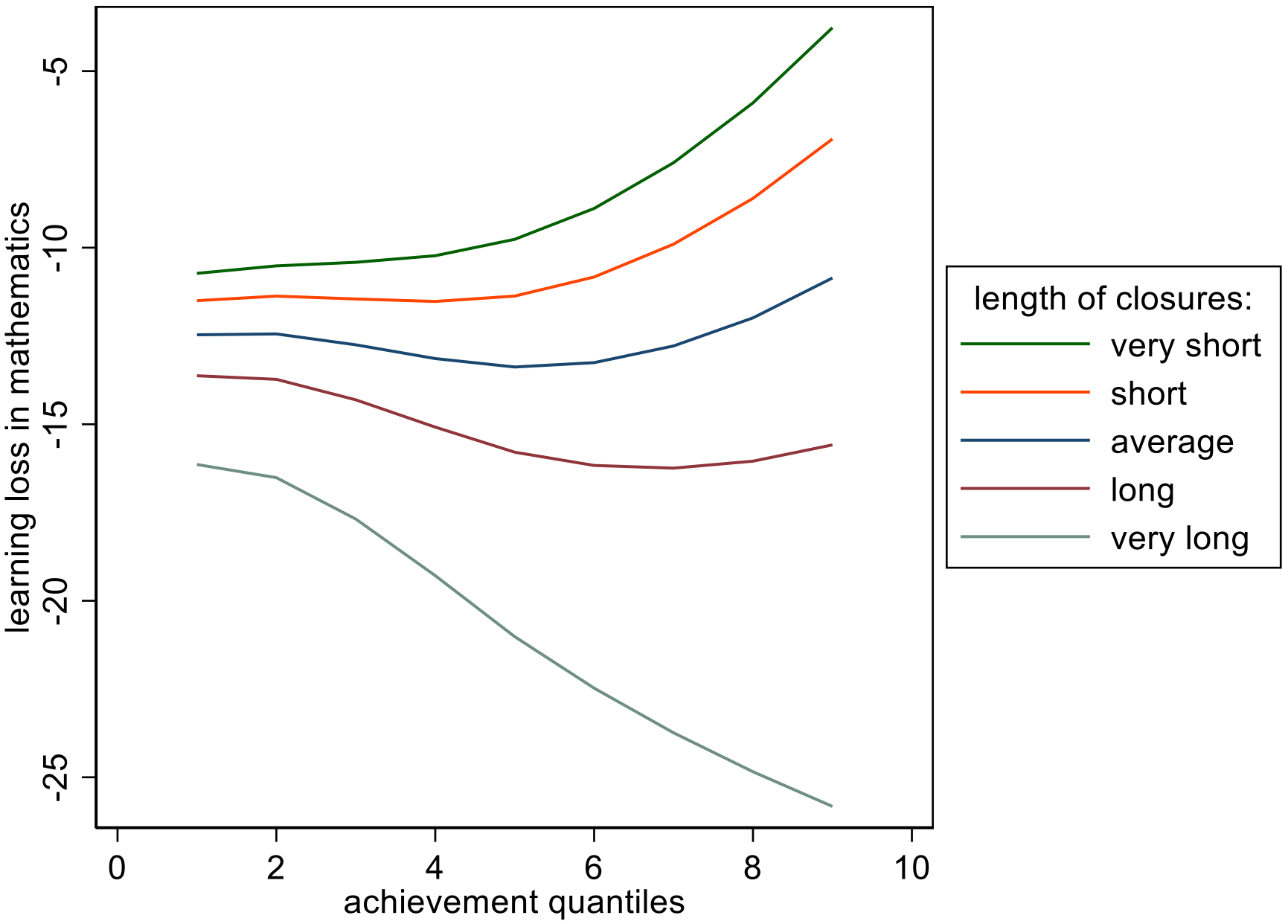

To gauge the magnitude of global learning loss during the pandemic, a team at the World Bank examined data from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) from 2018–2022, which tests fifteen-year-olds in math, reading, and science. Among the report’s many notable insights is a counterintuitive finding about math outcomes: in countries with the longest closures, high-achieving students experienced larger learning losses than their low- and medium-achieving peers.

Harry Anthony Patrinos, one of the authors, explained it like this in a Fordham Institute piece last month:

In countries with school closures of average duration—about 5.5 months—learning losses were similar for low-, average-, and high-achieving students. However, in countries with shorter closures, the best students experienced minimal setbacks, with the learning losses mostly being incurred by average- and low-achieving students. In countries with longer closures, the largest learning losses were experienced by high-achieving students.

And these achievement drops were sizable. “In countries with the longest closures, the low-achieving students lost around 16–17 points [on PISA’s score scale] or 20 percent of a SD,” note the authors, “while those at the top of achievement distribution lost 25 points or more (29 percent of a SD).” One-quarter of a standard deviation is approximately equal to a year’s worth of learning. (See figure 1, from the report.)

Figure 1. Learning loss estimates depending on student achievement quantiles and the length of closures

The U.S., at least as a whole, avoided this outcome, despite there being very lengthy closures in some places. Our learning losses by achievement group match the OECD average, Patrinos told me, meaning our low achievers lost more than our high achievers. But perhaps that’s because decisions were so locally determined and politically charged, with, for example, big red states like Florida and Texas keeping kids in classrooms far more than big blue states like California and New York. Indeed, because of this state autonomy, the U.S. was only one of three countries in the report that had zero “full closures,” per UNESCO, which defined these as “government-mandated closures of educational institutions affecting most or all of the student population” and tracked them worldwide throughout the pandemic.

Whatever the causes are, however, they’re beyond the scope of the report and my powers of divination, and speculation has limited value. Some takeaways and consequences, however, are worth exploring.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that being in school appears to be quite valuable for the learning of high achievers. This runs counter to cynical assumptions that these students attain their level of achievement primarily because of out-of-school factors, like household income, parent education level, and various forms of evening, weekend, and summer enrichment. Of course these things play a significant role, but the report’s findings suggest that classroom instruction is integral to the magnitude of their achievement.

If what happens in school matters for high achievers even more than for others, it follows that these students will not be fine regardless of the type of instruction that they receive. If formal schooling benefits high achievers this much, then the quality of that schooling—teachers, curriculum, rigor, etc.—likely matters greatly, as well. This is another way of saying that advanced education programs designed to maximize the achievement of these students are worth pursuing, and efforts to curb or scrap them are quite damaging.

Think of what these learning losses among high achievers mean for them, their nations, and the world.

First, the students themselves. Each and every child deserves an education that meets their needs and enhances their futures. They have their own legitimate claim on our conscience, our sense of fairness, and our policy priorities. When ill-considered policies and adult preferences led to pandemic-related school closures in many countries that were far longer and more numerous than necessary, all students were harmed, but none worse than those who had been high achievers.

Other significant costs were levied against countries’ (and perhaps U.S. states’) long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation—which translates to global impacts, too. High achievers are the young people most apt to become tomorrow’s leaders, scientists, and inventors, and to solve our current and future critical challenges. Most economists agree that a nation’s economic vitality depends heavily on the quality and productivity of its human capital and its capacity for innovation. While the cognitive skills of all citizens are important, that’s especially the case for high achievers. Using international test data, for example, economists Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann estimate that a “10 percentage point increase in the share of top-performing students” within a country “is associated with 1.3 percentage points higher annual growth” of that country’s economy, as measured in per-capita GDP.

Recall that the World Bank’s PISA analysis focused on math scores. Considerable research suggests that “math skills better predict future earners and other economic outcomes than other skills learned in high school,” and as the Wall Street Journal has observed in reference to U.S. NAEP results, “math proficiency in eighth grade is one of the most significant predictors of success in high school.” This suggests that the huge drops shown in the PISA data may reverberate through the rest of these students’ lives, their countries’ futures, and even the fate of the globe.

Bottom line: We don’t dare minimize the importance of formal education, and by extension, the value of advanced programming for high achieving students. At a time when these opportunities are under attack, schools have lost their sense of purpose, and our relationship with education seems to have become optional, this is an important and sobering reminder of these truths.