The closure of schools in response to the seismic disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic has left an indelible mark on education worldwide. As nations grappled with closures lasting varying lengths of time, the implications for student learning became increasingly evident. Recent data from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) have shed some light on the extent of the damage and its potential economic repercussions.

As is well known, PISA is an international measure of the academic achievements of fifteen-year-old students that serves as a critical barometer of global education standards. Its latest results (from 2022), incorporating data from both pre- and post-Covid assessment rounds, provide a comprehensive view of the pandemic’s still-evolving impact on academic achievement.

The key finding is stark. Between 2018 and 2022, there was an average decline in scores of 14 percent of a standard deviation, equivalent to seven months of learning. And that’s after controlling for pre-Covid trends! Because of the wide reach of the PISA assessments—175 million students in seventy-two countries—this illustrates the global nature of the pandemic’s negative effect on academic achievement. These results go beyond raw scores, as they have been revised using data over time and after taking into account deviations from the long-run mean. They are also consistent with many national studies, international comparisons, and other reviews of actual learning losses.

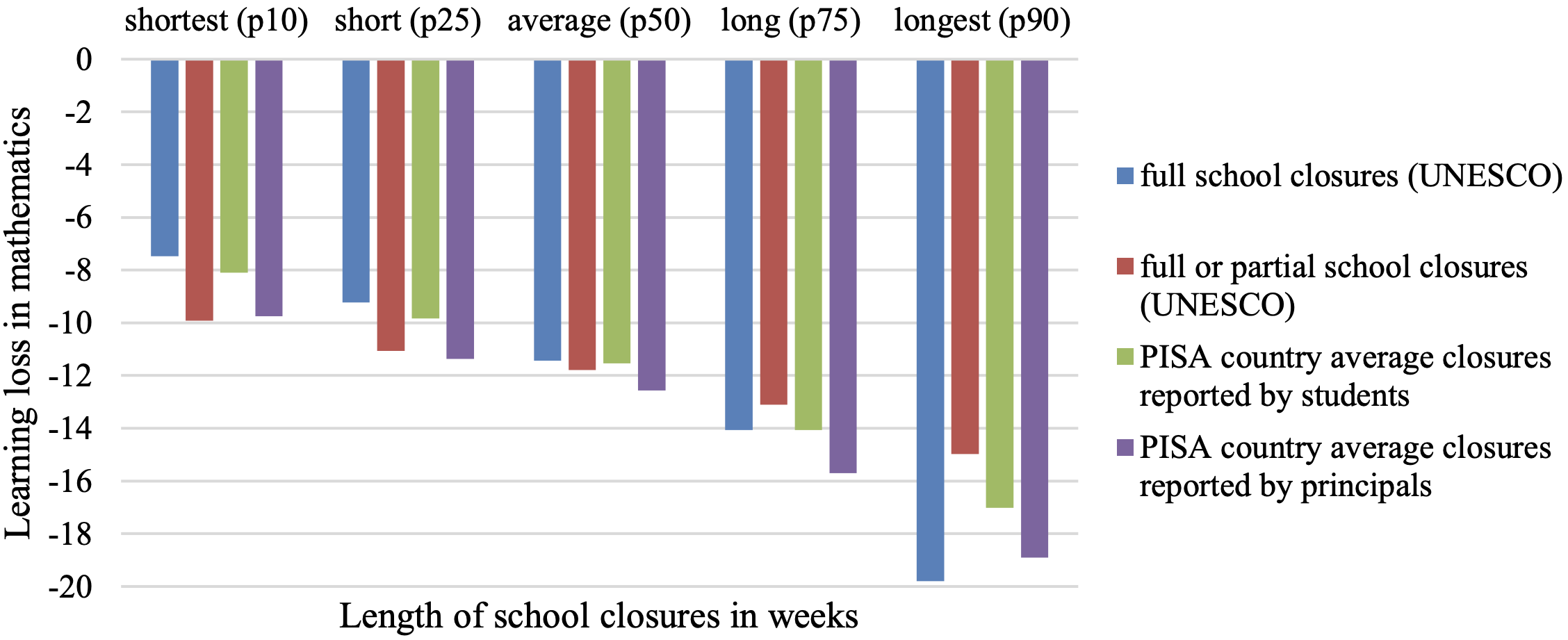

The extent of these losses in each country varied significantly depending on how long their schools were closed (see figure 1). Countries where schools were closed for shorter periods experienced relatively minor losses, whereas losses of up to a year’s worth of learning were observed in those countries with the longest closures. Immigrant students faced bigger setbacks, except in countries with longer closures where the learning loss for students with an immigrant background was similar to that of native-born students.

Figure 1. Learning loss depending on the length of school closure

Note: Losses shown are percent of a standard deviation (SD); in this case, 20 points are 0.20 SD; about 0.25 SDs are equal to a year's worth of learning.

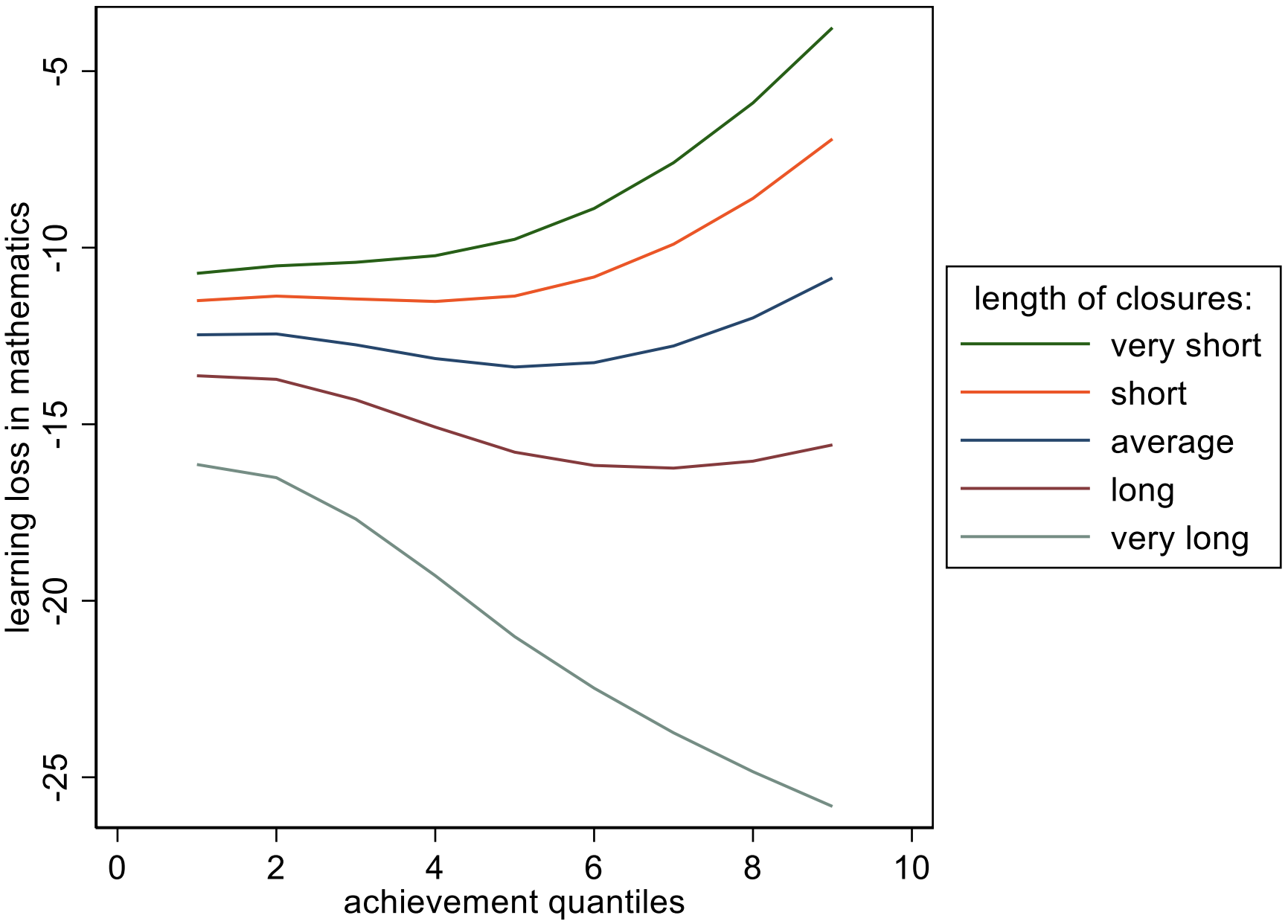

The PISA data also show differences in learning losses among students with different levels of performance (see figure 2). In countries with school closures of average duration—about 5.5 months—learning losses were similar for low-, average-, and high-achieving students. However, in countries with shorter closures, the best students experienced minimal setbacks, with the learning losses mostly being incurred by average- and low-achieving students. In countries with longer closures, the largest learning losses were experienced by high-achieving students.

While this seems counter-intuitive, differences in learning loss at different achievement levels in countries with short and long closures can be associated with differences in the overall achievement in these countries. Countries with the longest closures are also countries with the lowest achievement in PISA, while countries at the top of the PISA rankings closed schools for much shorter periods, on average. Thus, we see larger losses among the lowest-achieving students in countries with short closures and high achievement, similar losses across the achievement distribution in countries with the average length of closures, and larger losses among the highest achieving students in countries with very long closures and low achievement. This is what is shown in Figure 2. Nevertheless, losses are greater for the lowest achievers.

Figure 2. Learning loss estimates depending on student achievement quantiles and the length of closures

These results are consistent with a recent review of grade four student reading scores in the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). PIRLS is conducted by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). It measures reading proficiency of nine- to ten-year-olds. It has been conducted every five years since 2001. We used comparable data from fifty-five countries or regions from assessment rounds in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, and 2021. Our sample includes more than 1 million students participating in all rounds. The review showed that, in countries with relatively longer school closures, actual achievement in those schools that closed for more than eight weeks was lower than expected by 34 points, equivalent to more than a year of schooling. Learning losses were greater for those from schools closed for longer than average, while lower-achieving students experienced much larger educational losses than their peers.

Countries with no school closures achieved the same results as might have been expected based on their previous levels of achievement. This was the case in Sweden, where primary schools were never closed. Also, countries such as Denmark, Singapore, and a few other East Asian countries where schools were closed for only short periods and actions were taken to maximize the effectiveness of online education also experienced little or no learning loss. Such actions included giving schools extra resources for teaching and student well-being efforts

The consequences of the learning losses stemming from the Covid-19 school closures extend beyond the academic realm. The loss of human capital among the current generation of students will have enduring economic implications, both for the students themselves and for their countries. When they enter the labor market, their earnings will be lower than would have been the case in the absence of the learning losses, which will constrain their countries’ productivity, economic output, and growth and development.

The results from PISA and PIRLS are unequivocal: A crisis in education is has arrived, and low-achieving students are being disproportionately affected. As we navigate these challenges going forward, it will be imperative to make concerted efforts to find evidence-based strategies to mitigate the damage done by the pandemic closures and to enhance students’ learning outcomes. The time to act is now, for the sake of both current and future generations.