This study takes a look at Ohio's elementary-school teacher preparation programs and the extent to which they're training candidates in the science of reading. Based on analyses of programs' course materials and syllabi, the report identifies exemplary preparation programs that cover the five components of the reading science. Other programs, however, are lagging behind. The report offers recommendations that will better ensure that all incoming teachers are well-trained in the science of reading. Download the report, which includes the appendices, or read it on the webpage below.

Foreword

By Aaron Churchill

Fueled by decades of research about how children learn to read, attention-getting journalism on reading instruction, and thousands of parents frustrated with the approach to literacy in their own kids’ schools, the “science of reading” movement is sweeping across the nation.[1]

In response, state lawmakers are quickly enacting laws that aim to ensure that their schools use scientifically based reading instruction. Based on the 2000 National Reading Panel’s comprehensive review of literacy research, this science consists of five pillars that comprise effective reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Over the past decade, Ohio has enacted significant literacy reforms, including the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. But regrettably, the state hasn’t paid much attention to reading science. As a result, inferior instructional practices linger in too many Ohio classrooms. These methods include “three-cueing,” which wrongly encourages children to guess at words rather than actually read them. This practice, along with other discredited techniques, is ingrained in the “balanced literacy” and “whole language” programs that remain popular in many Buckeye schools. These methods hamstring kids from learning to read effectively and go against decades of reading science.

The result is high numbers of children struggling to read. Last year, 40 percent of Ohio’s third graders did not achieve proficiency on state reading exams. Non-proficient rates soar to 70 and 67 percent in Cleveland and Columbus, respectively, and 63 percent of third graders fell short of proficiency in the smaller districts of Lima and Middletown. Even in many of Ohio’s prosperous communities, more than a quarter of third graders aren’t reading proficiently.

Fortunately, there is light at the end of the tunnel. Earlier this year, Governor Mike DeWine unveiled bold initiatives that would overhaul reading instruction in Ohio. If approved by the legislature later this summer, his plan would require schools to adopt high-quality reading curricula that are aligned to the science of reading, forbid schools from using the “three-cueing” method, and build teachers’ knowledge and skill in teaching reading. Included also are millions in state funding that would support the implementation of reading science through new instructional materials and professional development. The governor’s plan appears to be on-track for approval by the full General Assembly at the time of this writing.

As longtime supporters of reading science, we at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute are encouraged by these movements and the promise they hold for Ohio students. But while curricula tend to receive the lion’s share of attention, one under-discussed area is the role of teacher preparation. If those who train teachers cling to disproven reading methods, Ohio’s new teachers will come into classrooms without the knowledge of reading science, and state- level curricular reforms won’t gain as much traction in Ohio classrooms.

To examine Ohio’s teacher preparation programs to see how they approach reading, we enlisted the support of the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ). Launched by Fordham two decades ago, NCTQ has a long track record of reviewing preparation programs in Ohio and nationally, as well as strong expertise in the science of reading. In fall 2022—months before we knew about the governor’s initiatives—we commissioned NCTQ to conduct a deep- dive analysis of teacher preparation in Ohio and the state’s reading policies, more broadly.

Do Ohio’s preparation programs adequately train prospective teachers in the science of reading? Which programs are exemplars and which are not? What steps can policymakers and education leaders take to strengthen teacher preparation—and reading instruction more generally—in Ohio?

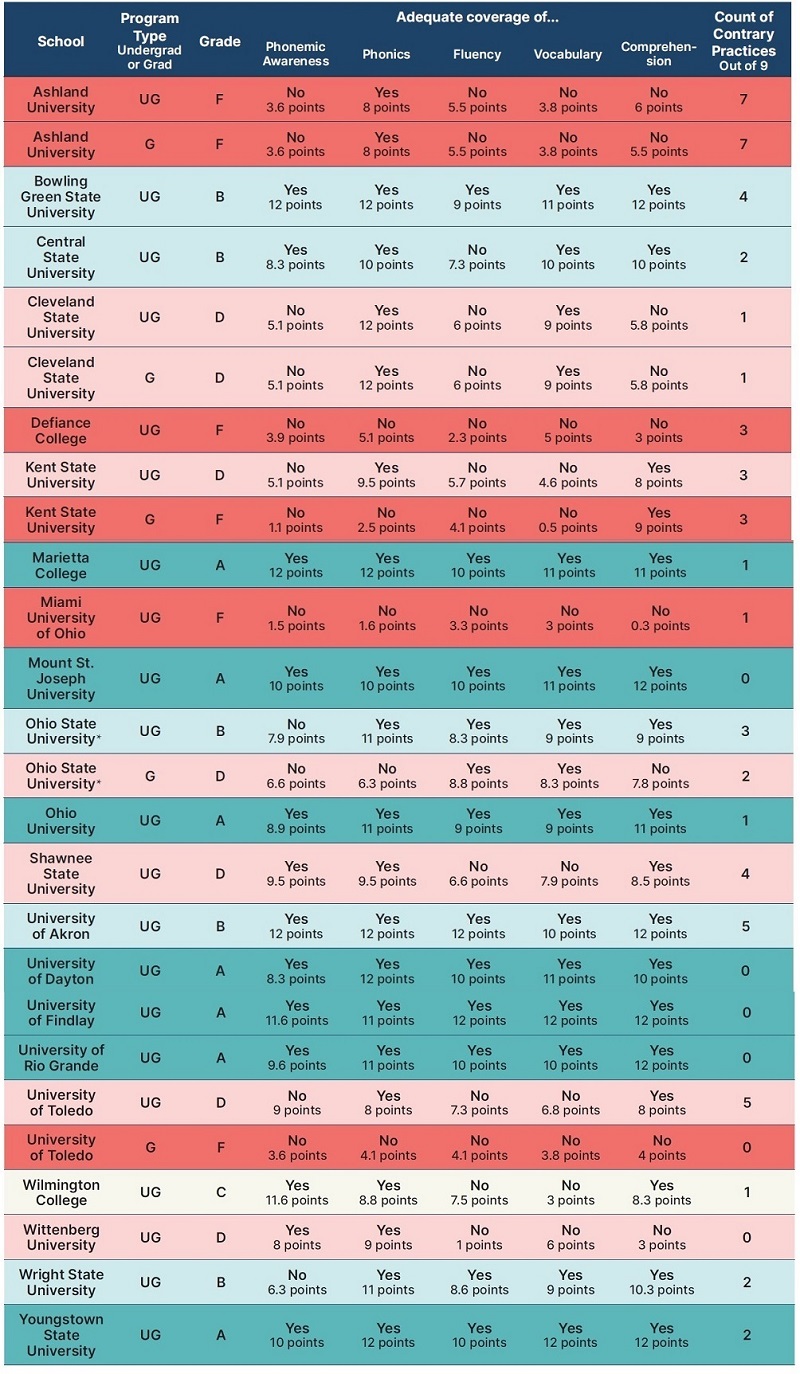

This report includes NCTQ’s brand-new findings on teacher preparation programs. Based on expert reviews of twenty-six undergraduate and graduate programs’ elementary education reading coursework, the analyses reveal the uneven training that prospective teachers receive in the science of reading. Seven praiseworthy programs earn A’s in this review, as they provide strong coverage in all five components of the reading science. Disappointingly, however, six programs receive F’s. Such programs fail to adequately train candidates in the science of reading—and actually promote methods that contradict it. The programs receiving A’s in this review enrolled 18 percent of the 1,700 students in elementary education programs, including three years of data through 2020–21, while 20 percent attended F-rated programs over the same time period. Regrettably, seventeen preparation programs, serving 23 percent of teaching candidates, chose not to cooperate with this review, despite repeated invitations. The executive summary identifies Ohio’s best and worst preparation programs, and the main report includes the grades of all twenty-six programs as well as a more detailed analysis of programs’ alignment with the science of reading.

How can Ohio ensure that all teaching candidates receive appropriate training and ongoing support in scientifically-based reading instruction? The report offers a number of important policy recommendations, notably including:

- Strengthen the state’s teacher preparation program approval process. Ohio currently implements a review and approval process for elementary reading programs, but it is largely driven by compliance measures rather than alignment with reading science. The state should hold programs more accountable for following the science of reading through in- depth reviews of their coursework and on-site reviews with reading experts as reviewers. Moreover, state approval (or not) to continue training teachers should hinge on these more rigorous evaluations. Recently, the Ohio House introduced provisions such as these in its version of the state budget bill. Lawmakers should ensure they pass and if enacted, the Ohio Department of Higher Education should rigorously implement the new review and approval process.

- Ensure that state-required reading coursework covers all five components of the science. Under Ohio law, elementary- and middle-school teaching candidates must take at least twelve credits of reading coursework. Of these, three credits must focus on phonics—a critical start for effective preparation. But current statutes are vague on the remaining credits. State lawmakers should strengthen the coursework provision by specifying that the other nine credits cover phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension.

Though an important policy lever, teacher preparation is one tool in the overall toolkit for improving reading instruction. Indeed, providing high-quality curricula and professional development are also critical to moving Ohio towards the science of reading. We strongly support Governor DeWine’s proposals in these areas, but legislators should shore up the plan in the following way:

- Add transparency and enforcement provisions to Governor DeWine’s high-quality curriculum requirement. As recommended in this report, his plan could be strengthened by adding provisions intended to ensure that those excellent proposals get put into practice throughout the state. To make sure that schools and districts actually follow the science, lawmakers should require the public disclosure of schools’ curricula in use and should specify penalties for non-compliance with the curriculum mandate.

Decades of research have yielded clarity about which instructional approaches effectively teach children to read, and which approaches don’t. With such unambiguous findings—and a pressing need to improve literacy—leaders in many states are now demanding instruction that is aligned to the science of reading. Yes, this policy shift cuts against the more traditional hands-off approach to curriculum and instruction. But as Governor DeWine himself said, “The evidence is clear. The verdict is in. Not all literacy curriculums are created equal, and sadly, many Ohio students do not have access to the most effective reading curriculum.”[2]

He and other state leaders are right. From the minute candidates enter teacher preparation programs until they leave the profession, teachers should be trained and supported to follow best practices in reading instruction. If Ohio can make this a reality, more Buckeye students will reap the lifelong benefits of being strong, fluent readers.

Executive Summary

Strong reading and literacy skills are essential to success in the modern workplace and for full participation in today’s society. The road to becoming good readers starts early, with elementary schools playing a critical role both in teaching children foundational reading skills and in giving them the rich academic content needed to comprehend various kinds of texts.

In order for children to learn to read proficiently, their teachers must understand the “science of reading” and apply practices aligned to it. This science focuses on five core components of effective reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension (a summary of each can be found here). A large body of research shows that when teachers anchor instruction in these components—while shunning ineffective approaches like “three-cueing,” which notoriously encourages children to guess at words—students are far more likely to become strong readers.

Building this instructional skill-set starts with the right teacher preparation, as well as strong supports for teachers, particularly beginning teachers, once inside the classroom. But do Ohio’s schools of education adequately prepare prospective elementary-school teachers in the science of reading? Or are they neglecting it and possibly instilling bad habits that will be hard to break? Separately, but just as important, how can schools continue to support teachers—including veteran teachers—in the reading science once they’re in the classroom?

The first part of this report analyzes twenty-six Ohio preparation programs—both undergraduate and graduate—that over three academic years ending in 2020–21 prepared 1,700 elementary teacher candidates, representing over 75 percent of the total completers during that time. Expert reviewers carefully examined course materials and syllabi to gauge programs’ alignment with the science of reading. The review yields mixed results, with some programs providing strong coverage of reading science and others barely scratching the surface (or worse, actually teaching candidates bad stuff). Key findings include:

- Just nine out of twenty-six elementary teacher preparation programs in Ohio provide adequate coverage of all five components of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension).

- Six programs adequately cover just one component of reading, or none at all.

- Most Ohio preparation programs do not give teachers sufficient hands-on practice across all five components. While candidates may observe lessons, many never get to practice, such as planning and demonstrating lessons in vocabulary and comprehension.

- More than half of Ohio programs promote multiple practices in their courses that are contrary to research-based methods (e.g., “three-cueing,” “balanced literacy,” or “leveled texts”). Teaching these practices can undermine the effect of scientifically based reading instruction, even if that is also being taught.

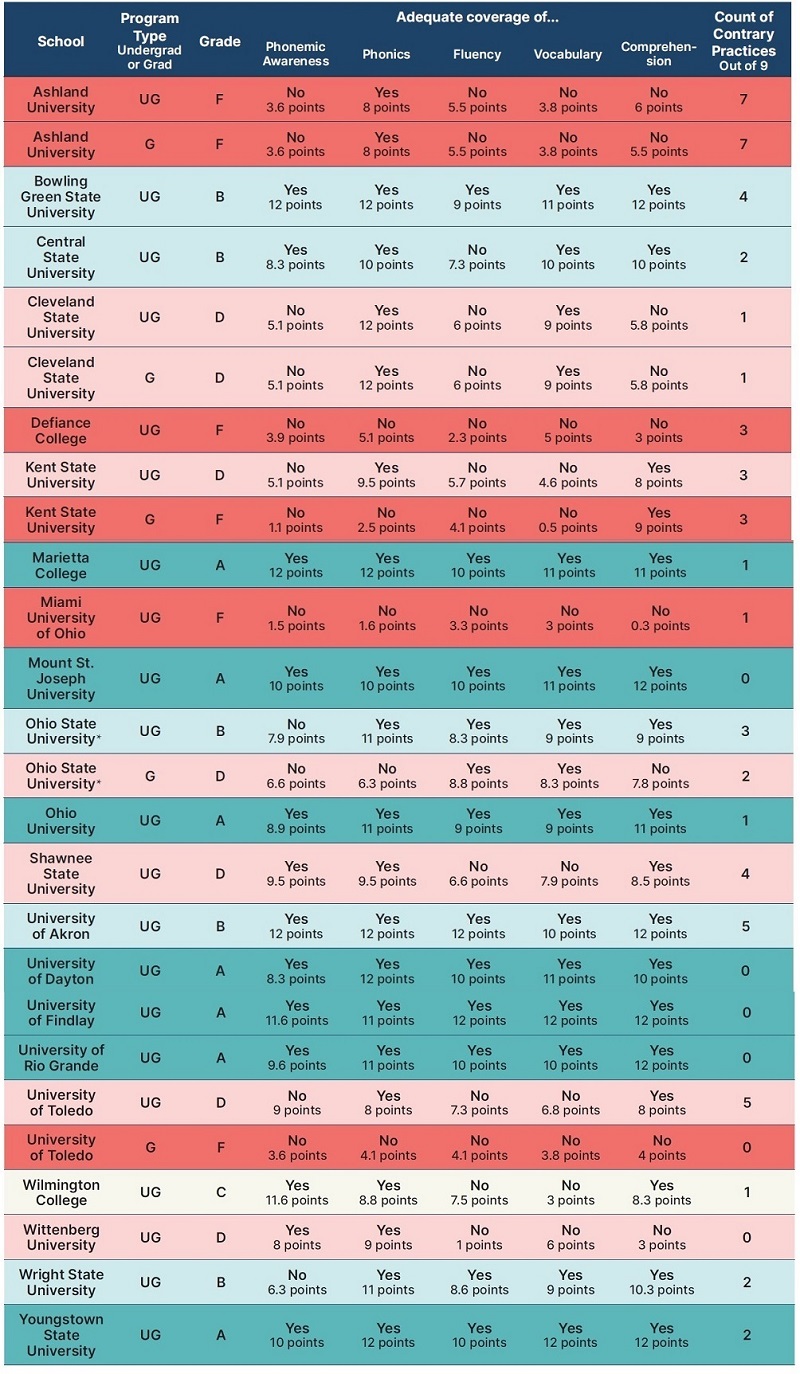

Based on analyses of alignment with the reading science, each program is assigned an overall letter grade. Those receiving A’s adequately cover all five components and make little or no use of contrary practices. In contrast, low-rated programs inadequately incorporate reading science into their coursework and may also promote multiple contrary practices.

- Seven Ohio programs earn overall A’s in our review: Marietta College, Mount St. Joseph University, Ohio University, University of Dayton, University of Findlay, University of Rio Grande, and Youngstown State University.

- Six programs earn overall F’s: Ashland University (undergraduate and graduate programs), Defiance College, Kent State University, Miami University, and the University of Toledo.

- Unfortunately, some of Ohio’s largest teacher preparation programs, such as those at Kent State University, Miami University, and Ashland University earn D’s or F’s. As a result, just 44 percent of Ohio’s elementary teacher graduates come from programs that receive an A or a B in this review.

The uneven results point to a need for stronger teacher preparation policies to ensure that all prospective primary-grade teachers in Ohio are trained in the science of reading. This report offers several recommendations, of which the most crucial are:

- Ensure that Ohio’s reading coursework requirements include all components of the science of reading. Currently, Ohio requires elementary teacher prep programs to dedicate twelve credit hours to reading instruction, including a three-credit course in phonics. The phonics requirement is praiseworthy, but state law is vague about the content of the other nine credits. Lawmakers should require an explicit focus on phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension for the remaining courses.

- Strengthen the state’s review and approval process for teacher preparation programs. Ohio currently implements a largely superficial review of preparation programs that doesn’t hold them rigorously accountable for training teachers in the science of reading. The Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) should strengthen this process by including reviews of course materials and on-site visits by trained reading experts that gauge program alignment with the science.

- Include consequences for preparation programs that refuse to follow the science. ODHE should issue either conditional approvals or non-approvals for programs that are unwilling to implement scientifically based reading instruction.

Strengthening teacher preparation will ensure that a future generation of educators is properly trained, but it won’t help current teachers who need to transition to scientifically based instruction. It also does little good to train teachers in the science of reading, but then allow their schools to use methods that are contrary to the science. The second part of this report discusses two additional areas of reform—curriculum and professional development—that legislators should leverage to ensure that all students, including those taught by veteran instructors, are learning to read through appropriate methods. Key recommendations include:

- Require schools to select vetted literacy curriculum. As proposed by Governor DeWine, Ohio should require all its public schools to adopt core, supplemental, and intervention materials from a state-approved list of high-quality reading curricula aligned to the science of reading. When implementing this requirement, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) should decline to approve curricula that rely on weak instructional methods (e.g., Fountas & Pinnell Classroom and Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study).

- Make schools’ reading curricula public, while specifying consequences for non-compliance. Legislators should strengthen the governor’s literacy plan by adding transparency and enforcement provisions that ensure that schools truly follow the science of reading. Lawmakers should further specify what exactly the professional development will entail and include a requirement that the professional development be approved by the Ohio Department of Education.

- Ensure high-quality professional development, with clear expectations for teacher improvement. In his budget outline, Governor DeWine proposed significant funding to support professional development in the science of reading. This is much-needed in a state where too many current teachers have been poorly trained. However, lawmakers should further specify what exactly the professional development will entail and include a requirement that participants demonstrate acquisition of knowledge in the science of reading through an assessment system.

The research is clear about how reading develops and the best methods to teach children how to read. Teachers deserve access to this knowledge and skills, and every student deserves to be taught in a way that ensures their success. With a strong move towards the science of reading, more Ohio students will have the literacy foundation needed to succeed in school— and in life.

Introduction

All children need to learn to read proficiently, but that’s not going to happen until and unless all their early-grade teachers equip them with the essential skills and tools. To that end, all teachers need rigorous preparation and support that empowers them to help students achieve this goal. Yet more than one-third of fourth graders[3] across the country cannot read at a basic level.[4] Not learning how to read fluently in elementary school has dire lifelong consequences. Students who are not reading at grade level by the time they reach fourth grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school.[5] This, in turn, causes big problems for them as adults: lower lifetime earnings,[6] higher rates of unemployment,[7] and greater likelihood of entering the criminal justice system. Even more alarming, the proportion of students who cannot read proficiently by fourth grade is higher for students of color, students with disabilities, and those who grow up in low-income households—thus perpetuating existing disparities.[8]

Unfortunately, Ohio’s reading performance mirrors that of the nation. The most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) (2022) shows that only 35 percent of fourth-grade students in Ohio are proficient (or above) in reading. Students living in poverty have much lower fourth-grade reading proficiency rates, with only 20 percent of students eligible for the National School Lunch Program scoring proficient or above, compared with 47 percent of students from higher-income families. The gap between Black and White students is also large, with only 14 percent of Black students reading proficiently, compared with 39 percent of White students. These gaps in proficiency rates for different student groups have widened over the past two decades – and having nothing to do with student ability and everything to do with how and what they are being taught.

These results are preventable. Effective literacy instruction can dramatically change the life outcomes of thousands of Buckeye students. The National Institutes of Health have been studying how children learn to read for over six decades, producing strong evidence demonstrating that all but about 5 percent could learn to read if:

- their teachers are taught the most effective, scientifically proven methods that they implement in their classrooms;

- schools purchase curriculum materials based on this science of reading;

- teachers receive targeted support from experts in the science of reading; and

- when necessary, students receive targeted, intensive support as they learn to read.[9]

So what is the “science of reading”? Building on comprehensive reviews of studies about how children learn to read, the NIH-sponsored National Reading Panel in 2000 concluded that effective literacy instruction includes five core components: Developing students’ phonemic awareness allows them to understand the sounds made by spoken words, and phonics instruction enables students to systematically map those speech sounds onto letters and letter combinations so they can “decode” words. Teachers must promote extended practice to read words and passages so that students develop their fluency, which allows them to devote their mental energy to the meaning of the text. It is also critical for teachers to build student vocabulary, a skill closely connected with comprehension, ensuring students understand what is being read to them and what they will read themselves.[10] The science of reading includes the methods, based on research, that help children learn to read. Importantly, the science of reading is more than just phonics instruction. All the components, working together, are essential to developing strong readers.

While Ohio has begun to tackle reading instruction with some pockets of success, much work remains to be done. In many districts, Ohio not only neglects proven methods, but also actively propagates disproven methods. One significant challenge for the state is its strong historical ties to the “whole language movement,” an approach to literacy instruction that ignores or deemphasizes key components of reading science and instead includes disproven methods of teaching reading. Particularly problematic is the three-cueing method, which instructs students to guess a word based on context, such as a picture or the first letter of the word, rather than learn to sound it out.[11] The state is also home to architects of popular reading materials that perpetuate ineffective teaching strategies and are disseminated through curriculum materials and professional development. For example, the Fountas and Pinnell Classroom curriculum was co-developed by faculty at Ohio State University, and, despite recent national evaluations[12] that deem it misaligned to the science of reading (e.g., missing are daily opportunities to practice decoding sounds and spelling patterns), the authors continue to stand by their work. As a result, many Ohio districts are steeped in the use of misaligned curricula, and many Ohio teachers leave costly trainings having learned debunked instructional practices.

Similar shortcomings afflict intervention programs designed specifically for struggling readers. Reading Recovery, an intervention program introduced by Ohio State University in 1984, was implemented widely across the state and the country and—to be fair—some early evaluations found positive effects in first grade. However, a more recent study has found that students who participated in Reading Recovery actually performed significantly worse on third and fourth-grade reading outcomes than comparable students who never had this intervention.[13]

The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) has been tracking the implementation of the science of reading in teacher preparation and state policy for well over a decade. Over the years, NCTQ has also engaged with practitioners and advocates in Ohio to encourage scientifically based reading instruction. We have seen promise and progress, such as the 2012 enactment of the state’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee, a significant early literacy reform package that requires interventions for struggling readers. More recently, Governor DeWine has proposed legislation that would require scientifically based reading instruction across the state. To assist with implementation, the governor’s proposal also includes funding for new curriculum and teacher training.[14]

This report provides research and recommendations to further support the rigorous implementation of scientifically based reading instruction in Ohio. It includes a new analysis of Ohio’s teacher preparation programs and the extent to which they teach the science of reading. Teacher prep programs play a critical role in providing aspiring teachers with the knowledge and skill to effectively teach children to read–and their graduates impact thousands of Ohio’s children. If teacher preparation programs use disproven practices to teach aspiring teachers, Ohio’s K-12 schools will need to bear the burden of time and expense to retrain their teachers or risk exposing students to poor instructional practices. Based on the analyses of teacher preparation programs, the report also discusses opportunities for state legislators to better ensure that prospective teachers are properly trained in the science of reading. Beyond teacher preparation, the report examines and offers policy suggestions that would strengthen Ohio’s promising initiatives around high-quality instructional materials and professional development.

The status quo is far from inevitable. With research in hand and strong leadership across the state, Ohio can make big changes on behalf of kids. The current reality is devastating. We know the solution to this reading crisis, and we need to implement a comprehensive approach at scale. Ohio’s 1.6 million students need to learn to read.

Teacher Preparation

Scientifically based reading instruction is grounded in research on how students learn to read. It builds off the 2000 National Reading Panel report,[15] which emphasizes the importance of alphabetics (phonemic awareness and phonics), fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension and is based on decades of research. A 2016 report by the Institute of Education Sciences (updated in 2019) offers teachers actionable, evidence-based recommendations to teach reading. It also examines the recommendations of the National Reading Panel and confirms the validity of the 2000 report.[16]

In Ohio, as in the rest of the United States, many elementary teachers never get trained in scientifically based reading instruction during their time enrolled in teacher preparation programs. Unbeknownst to them, they enter the classroom well-intentioned but inadequately prepared to teach kids to read. Ensuring that all teachers are prepared to teach reading aligned to the science before they enter the classroom should be a key goal of schools of education as well as state policymakers.

To gauge how well states—and individual preparation programs—are training prospective teachers in the reading science, NCTQ will soon release a national report, The Teacher Prep Review: Strengthening Elementary Reading Instruction. This update of NCTQ’s 2020 analysis includes several revisions aimed at raising expectations for the time and attention that programs dedicate to the five core components of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension). These updates were based on a multi-year revision process[17] that included significant input from experts and practitioners, including some from Ohio. (An overview of the methodology can be found in Appendix A.) The revised methodology also accounts for the presence of flawed reading practices that endure in some teacher preparation programs. More information about the scoring rubric, details on how the instructional approach targets were set, the sample of programs, information about contrary practices, and specifics on how the analysis was completed can all be found in the Reading Foundations Technical Manual.[18]

NCTQ reviewed course materials provided by nearly 700 elementary teacher preparation programs—26 in Ohio—seeking evidence that they are guided by what is known empirically about how to effectively teach reading in the early grades. To determine if a program adequately covers each core component, e.g., phonics or vocabulary, NCTQ looked for evidence across four instructional elements: background materials, instructional time, measures of knowledge, and practice. Four questions guided the analysis:

- Does the program use background materials/textbooks aligned to the science of reading?

- Does the program dedicate sufficient instructional time to teaching each component?

- Does the program use measures such as tests, quizzes, or assignments to verify the candidate’s acquisition of knowledge?

- Does the program offer ample opportunity for candidates to practice the implementation of each component?

Programs that exhibit a preponderance of evidence that they address the component (i.e., earning eight out of 12 points, or 67 percent) across these four instructional elements are deemed to “adequately cover” the component. The following reports the results from analyses of Ohio’s teacher preparation programs in reading, which train roughly 70 percent of teacher candidates across Ohio.

How well do Ohio’s teacher preparation programs address scientifically based reading instruction?

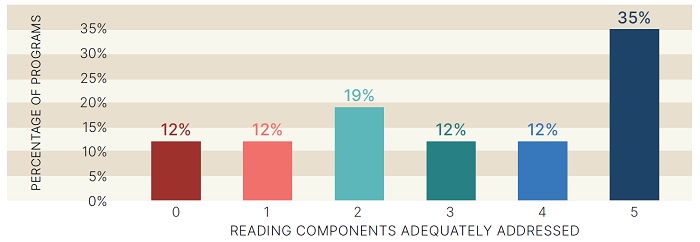

Across the state, teacher preparation programs vary significantly in the extent to which they train teachers in the science of reading. On the one hand, 35 percent of Ohio’s programs (nine out of twenty-six) adequately cover all five core components of reading. On the other hand, 23 percent cover one or zero components adequately (six out of twenty-six). The overall average program in Ohio adequately addresses only three of the five components of scientifically based reading instruction. While Ohio ranks 14th in terms of the number of components the average program covers, the state also ranked 8th in the average number of practices taught that are not aligned with the research, a stark example of the dichotomy that exists between programs in implementing reading science. The typical preparation program struggles to provide teaching candidates with comprehensive training in the science of reading.

Figure 1: Percentage of Ohio teacher preparation programs by the number of reading components they adequately cover

Five Core Components

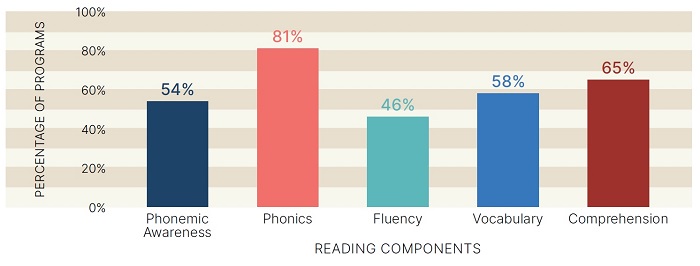

All five components are equally essential, so it is important to unpack which components are in greatest need of additional attention in Ohio teacher prep programs. Most likely due to the specific state policy requiring programs to deliver a three-credit course in phonics, one strength of Ohio’s preparation programs is that 80 percent provide adequate coverage of phonics (though it’s alarming that 20 percent do not). Meanwhile, roughly 60 percent of programs provide adequate coverage of comprehension and vocabulary. Phonemic awareness and fluency are the two least-covered components in Ohio, with roughly 50 percent of programs covering each. This pattern mirrors our national analysis, which found that preparation programs across the country tend to have the least coverage of phonemic awareness and fluency.

Figure 2: Percentage of teacher preparation programs that adequately cover each reading component

Teaching content contrary to research

The research is clear on how skilled reading develops and on the instructional practices most likely to result in children becoming skilled readers—as well as the methods that their teachers should not be using, methods that run counter to the research. Even when programs teach these contrary practices alongside research-based methods, they risk confusing aspiring teachers as well as their pupils and may lead new teachers to implement debunked practices that prevent students from becoming efficient readers.

In their analysis of course materials, NCTQ expert analysts collected instances in which there was evidence that a preparation program includes at least one of nine identified practices that run contrary to the science of reading. These practices include the following, with a brief explanation of each (for detailed information about what these consist of and why they are problematic, see Appendix B):

- Three-cueing systems

- Running records

- Miscue analysis

- Balanced literacy models

- Guided reading

- Reading Workshop

- Leveled texts

- Embedded/implicit phonics

- Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA), Informal Reading Inventory (IRI), or Qualitative Reading Inventory (QRI)

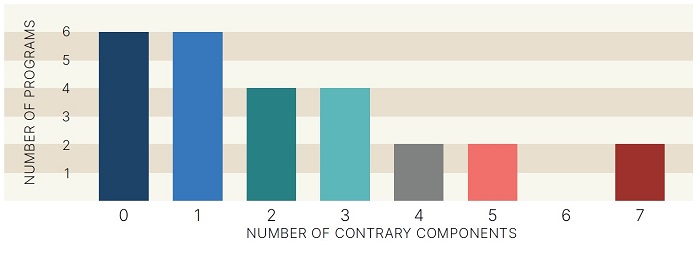

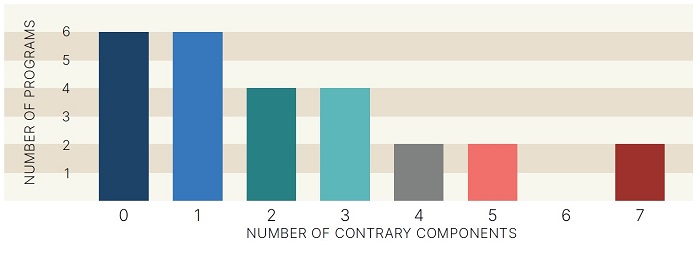

Overall, Ohio teacher prep programs incorporated more of these contrary practices than, on average, that of the country as a whole. The average Ohio program dedicated some instructional time to more than two practices (2.2) that run contrary to scientifically based reading instruction, ranking eighth highest in the country, with guided reading and running records found most commonly. Figure 3 below shows that six programs include four or more contrary practices, while fourteen out of twenty-six programs include two or more practices.

Figure 3: The Number of Contrary Practices Taught in Ohio’s Programs

- Description of practices not aligned with research

-

Three-cueing systems: Also known as the structure/meaning/visual system (SMV), three-cueing describes the support for early word recognition that relies on cues that helps students guess the word based on context or pictures as well as the letters in the word.

Running records: Running records is an assessment in which a teacher observes a student’s oral reading of a passage and records the number of errors to calculate the accuracy level, which informs students’ reading levels.

Miscue analysis: Grounded in the idea students use clues, or “cues,” to determine what a word is, miscue analysis is a practice employed by teachers to use errors in students’ reading to determine the strategies they’re using to read (or guess) words, which can distract from helping students learn to decode the words.

Balanced literacy models: Balanced literacy models represent an approach to reading characterized by the use of read-alouds, shared readings, small group guided reading, and independent reading, typically relying heavily on leveled books and focusing on meaning-based instruction. In contrast to structured literacy, balanced literacy models often eschew the explicit, systematic teaching of phonemic awareness and phonics skills, demonstrating a preference for approaches emphasizing context clues, like three-cueing.

Guided reading: Guided reading is an approach to reading instruction where students are grouped according to their “reading level” and asked to read appropriately “leveled texts.” Instruction focuses on reading for meaning, and the practice typically promotes using cues (including background knowledge and pictures), English syntax, and visual information (including sound- symbol relationships).

Reading Workshop: Units of Study is commonly called, “Reading Workshop,” and is a balanced literacy curriculum characterized by the use of read-alouds, small group-guided reading, shared readings, and independent reading.

Leveled texts: Leveled texts are “reading materials that represent a progression from more simple to more complex and challenging texts.” These texts are often used based on the premise that student learning should primarily occur using texts at their “instructional level,” which they read with a high (but not perfect) level of accuracy with some support from a teacher.

Embedded/implicit phonics: In contrast to explicit (or synthetic) phonics instruction, embedded or implicit phonics instruction links the reading of children’s literature or texts for the purpose of developing meaning, where “sound/spelling correspondence are inferred from reading whole words and introduced as students encounter the in text.”

Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA), Informal Reading Inventory (IRI), or Qualitative Reading Inventory (QRI): These assessments are typified by a student reading orally from a passage (DRA), or a list (IRI, QRI), while an instructor tracks student errors.

Why are these practices so concerning?

While some children will learn to read with little instruction, that is not the case for most students. For example, guided reading is a key component of balanced literacy models and consists of small-group lessons where students are grouped by reading levels and matched with leveled texts. Guided reading teachers prompt students to use reading strategies that involve three sources of text information or cues. Groups of students participate in teacher read-alouds, text reading and writing in a variety of formats, and mini-lessons designed to teach how letters and words work. While multiple studies have found explicit instruction to be more effective, one study, in particular, found that for phonological decoding, explicit instruction produced gains twice as great as guided reading; and on two measures of comprehension, explicit instruction delivered gains four times those from guided reading.[19]

Another popular practice that is not supported by reading science is the “three-cueing system.” Children who encounter a word they do not recognize are instructed to use one of three strategies: “guess what the word might be” based on context; “look at the picture to help guess what the word might be;” and “look at the first letter to help guess what the word might be,” and if the guess makes sense, then check to see if it “looks right.”[20] Despite widespread use by K-2 and elementary special education teachers, and the inclusion of three-cueing in curriculum currently in use in Ohio, such as Fountas and Pinnell, reading experts discourage guessing techniques because they represent lost opportunities to help children practice decoding,[21] and the strategy is an ineffective one for reading advanced texts.[22]

Too many Ohio programs incorporate practices that aren’t supported by science and that can undermine the effect of scientifically based reading instruction, even if the science-based methods are also being taught. Assessment strategies, such as running records, make up several practices that top the list of practices still being taught in Ohio teacher preparation programs that run contrary to research. The result is confusion at best and damaged reading skills at worst.

Practice Makes Perfect

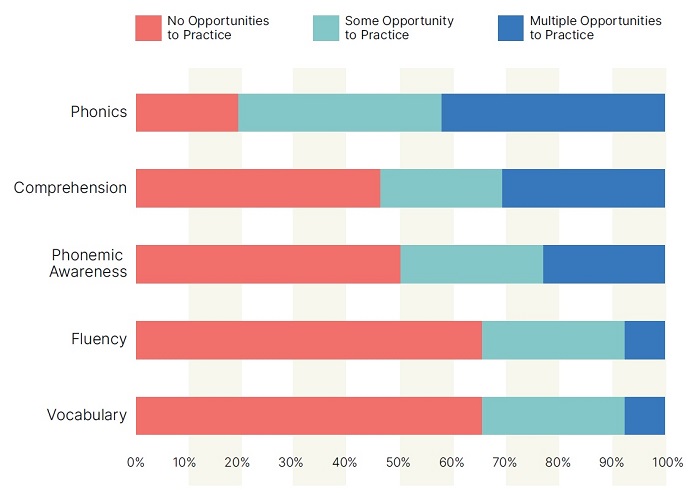

It seems intuitive: To get better, you need to practice. In teacher preparation, practice takes many forms, such as one-on-one tutoring with a student, administering a mock assessment to fellow teacher candidates, or conducting a lesson during a field experience. Regardless of the format, practicing reading instruction methods is essential to preparing new teachers to implement them in their own classrooms.[23] For this review, analysts assessed whether teacher prep programs in Ohio provided any type of practice opportunity for each specific core component (e.g. phonics, fluency) during coursework. In Ohio, of all the components, programs give candidates the most opportunity to practice phonics instruction; yet barely two in five give candidates multiple opportunities to practice this important skill. Two programs out of three offer no practice opportunities in fluency or vocabulary.

Field experiences (or practice teaching opportunities in a real school setting) are often designed to coincide with a course, but do not prescribe practice opportunities connected to specific components of reading. For example, students may spend hours in the field, but the practice is not connected to the course concepts and the reading components, and depends on what the cooperating teacher is covering. A student teacher may never be required to administer a reading assessment of students’ comprehension or demonstrate how they would support a multilingual student to gain phonemic awareness in English.

Figure 4: Opportunities to practice by reading component in Ohio programs

Individual teacher preparation program performance

The good news is that Ohio is home to several education schools identified by NCTQ as exemplary because they adequately follow the science of reading and teach zero contrary practices. Thus, they serve as models to the rest of the country. These exemplary programs include the University of Dayton, the University of Findlay, Mount St. Joseph’s University, the University of Rio Grande, and Youngstown State University. The bad news is that 23 percent of programs in the state adequately cover none or just one component of the science of reading and multiple programs teach four or more (out of nine) contrary practices. The table below has a full breakdown of performance by individual program.

*This program submitted additional materials after the deadline; pending review scores may be updated.

*This program submitted additional materials after the deadline; pending review scores may be updated.

Note: Programs are deemed to have adequately covered a core reading component if they earned at least eight out of twelve points. Grading for a program is based on the number of reading components for which the program receives credit. Each component (phonemic awareness, phonics fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension) is equally weighted. If a program teaches four or more contrary practices, its letter grade was reduced by one grade, affecting six programs in Ohio. For more specific information on the grading methodology see Appendix A. For a list of programs that declined repeated invitations to participate, see Appendix C.

Policy Discussion and Recommendations

Teacher preparation lays the foundation for aspiring elementary teachers to teach reading, and it is a critical policy lever that states can use to improve reading instruction. Strong state policies can help to ensure consistency across prep programs so that all prospective teachers are well-prepared to implement scientifically based reading practices. This section analyzes current state policy and provides recommendations about how policymakers can ensure that Ohio’s teacher prep programs deliver that crucial set of knowledge, skills and understanding.

Preparation standards

Standards for what teacher candidates must know and be able to do are crucial for setting up future teachers to succeed. The purpose of standards is to set an expectation that all aspiring teachers acquire the same knowledge and skills—aligned to the research—and promote consistency across programs. Ohio has some strong measures currently in place to signify the importance of reading. The state requires all aspiring teachers to take at least three credit hours of coursework in reading instruction. To get licensed as an elementary, middle-school or special-education teacher, candidates must complete 12 credit hours in the teaching of reading, which must include a distinct three-credit-hour course in the teaching of phonics.

The foregoing analysis shows that teacher prep programs in the Buckeye State generally comply with this requirement and dedicate sufficient time to phonics, with 80 percent of programs meeting expectations on the phonics component in the NCTQ analysis. While the law is vague regarding what else should be covered in the “teaching of reading,” the Ohio Department of Higher Education in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Education assembled a panel of literacy faculty to develop standards, known as the Reading Core Standards, to guide professors who are preparing candidates with the necessary knowledge and skills.

A review commissioned by NCTQ found those standards, which were finalized in 2018, to be relatively strong.[24] They would be stronger, however, with a few revisions by removing references to items that lack a strong research base such as running records (Standard 8.1), the social construct idea of comprehension (Standard 5.1), and reference to leveled readers (Standard 5.2). On a positive note, the Reading Core Standards include expectations on how to teach reading to special populations of learners, including English learners, students who struggle to learn to read or have dyslexia, and students who speak English language variations or dialects.

Recommendation:

- Update the reading coursework requirement to be more explicit about the content preparation programs must include. Currently, Ohio requires programs to dedicate 12 credit hours to reading instruction, with a specific required three-credit course in phonics. Present policy, however, is vague about the other nine credits. It only specifies that those courses include “instructional strategies for teaching reading, the assessment of reading skills, and in the diagnosis and remediation of reading difficulties.” No specifics are given as to which knowledge and skills should be taught within those broad categories. State leaders should amend the law to explicitly refer to the Reading Core standards[25] (with the revisions suggested above) and include an explicit focus on phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension within the remaining nine credit hours.

Program approval policies

While preparation standards are important, it’s at least as important to have policies that hold programs accountable for following those standards. Program approval policies are a key lever in improving teacher preparation.

The Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) has authority to approve educator preparation programs. This is highly relevant for Ohio, given there are programs with strong evidence of scientifically based reading instruction and others that are clearly lagging behind. Today, ODHE largely relies on the norms and processes of external bodies such as the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) when gauging the approval-worthiness of institutions that offer programs leading to educator licenses. While an ODHE representative attends the site visit and reviews the materials submitted to the accrediting body, along with other documents to verify alignment with Ohio standards, the site visit is currently led by the accrediting body. The Chancellor’s staff will then use materials submitted prior to the visit,[26] observations during the visit, and the final accreditation report to make their final recommendation, which may or may not pay serious attention to the implementation of the science of reading.

Despite current efforts to require 12 credits devoted to reading instruction and the public reporting of some program data (licensure pass rates, survey results), it is clear, based on our analyses, that not all programs are meeting expectations related to reading instruction. ODHE and ODE produced guidance with the Reading Core standards, but those are not specifically referenced in the current law. Revising the requirements for prep programs to include reference to the Reading Core Standards would provide clear expectations for teacher preparation programs and give leverage to hold the programs accountable. Currently, the lack of specificity in the law most likely makes any other coursework requirements, other than phonics, difficult to enforce. For example, the only thing noted as a requirement, aside from the specifics on phonics, is “training in a range of instructional strategies for teaching reading, in the assessment of reading skills, and in the diagnosis and remediation of reading difficulties.” This broad definition leaves wide latitude for programs to provide instruction on content not aligned with research-based practices.

Recommendations:

- Expand the depth of program reviews, specifically to inspect the alignment with scientifically based reading instruction. ODHE should deepen its program review process for reading instruction. For example, the state should require that the program approval process involve a review of syllabi by reading experts in order to examine the alignment of content and ensure aspiring teachers have opportunities to practice their skills. The state should also strengthen the approval process by including trained reading experts on the site visits. Other states conduct detailed site visits of teacher preparation programs that include classroom observations and teacher candidate interviews to gauge the implementation of scientifically based reading instruction. Colorado has cited the inclusion of reading experts on their site visits as incredibly valuable to determining the depth of implementation of scientifically based reading instruction in teacher preparation programs.

- Institute consequences for non-compliance. At the end of the day, the state must be willing to issue either conditional approval or non-approval for programs that are unwilling or unable to implement the science of reading and prepare teachers to teach scientifically based reading instruction. This approach has worked well in Colorado,[27] which has used conditional approval with required actions and strict timelines, to bring several programs into alignment with the reading science.

- Require a reset of all programs to ensure alignment. The Chancellor of Higher Education currently has the authority to call for an immediate review of programs. This authority could be used to verify that every program in the state aligns its reading coursework on an identified timeline, rather than waiting for their next approval cycle, which may be up to seven years away. For example, the state could require that all elementary educator preparation programs (or programs certifying any PK-5 teacher) submit evidence of alignment with revised Reading Core standards. Programs would be required to submit verification of alignment through a process established by the Chancellor. Colorado uses a matrix[28] to collect evidence ahead of a site visit and it requires programs to identify where candidates acquire certain knowledge in the science of reading as well as when during the program they practice it. Once this type of matrix or rubric is established, Ohio could then conduct a site visit to verify evidence and begin implementation of a more rigorous teacher preparation approval process.

- Require first-time pass rates on state licensure exams as part of program approval and include them on annual data reporting. NCTQ considers the Foundations of Reading licensure exam to be a strong test aligned with the science of reading. Moreover, Ohio should require programs to publicly report first-time pass rates (as opposed to only “best attempt” rates, which include retakes). The state should also use the first-time pass rates in its program approval process. This would put some additional pressure on preparation programs to comprehensively train teachers in the reading science by encouraging them to ready candidates to pass a rigorous licensure exam on their first try (rather than needing to take the exam multiple times–at great cost to candidates).

- Provide opportunities for support. ODHE, in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Education, should provide opportunities for faculty members who teach reading to participate in state-led professional learning opportunities on scientifically based reading instruction. ODE could also create a community of practice, using the local programs in Ohio that are some of the best in the country to provide support to peers shifting to scientifically based approaches. The state could also consider partnering with organizations such as Teacher Preparation Inspection-US (TPI) or Barksdale Reading Institute to help with capacity-building efforts and to support preparation programs implementing scientifically based reading instruction.

Teacher Development and Supports

The preparation of future teachers is key but not the only action, as it deals with a small fraction of those teaching Ohio pupils today. Yet many, probably the vast majority, of current teachers were trained to teach reading via methods that don’t align to the science of reading.[29] So providing them with in-service training is also critical. Moreover, even the best- prepared candidates will struggle in an environment where resources and expectations are not aligned to scientifically based reading practices. A new teacher may have learned the five components, but if they are directed by their schools to use instructional materials that run counter to their training, they will likely adjust their instruction to what their employer requires. Therefore, it is important that the state enact policies aimed at those already in classrooms, too. In this section, we discuss policies that support the use of high-quality core instructional materials, professional development, and supplementary reading intervention programs for students.

High-quality instructional materials

All teachers should have access to high-quality instructional materials aligned with the science of reading. NCTQ reviewed the “model curriculum” made available to Ohio educators on the Ohio Department of Education website and found that, while it includes an alignment to the science of reading in many instances, it also includes many references that run contrary to evidence-based practices. For example, several early grade-level materials reference texts and source material perpetuating three-cueing and balanced literacy approaches.[30] In kindergarten, the model curriculum includes instructional strategies such as “guess the covered word,” where teachers are instructed to do the following: “Take a sentence from the book and record it for full class viewing (whiteboard, projected, etc.). Cover one word in the sentence. Model how to figure out the covered word (circle context clues, size, and shape of the word, revealing first letter, etc.).” This is especially problematic, given that it reinforces notions that reading is guesswork, rather than a process of building phonics and phonemic awareness skills.

Ohio’s current model curriculum sends mixed messages to teachers and ultimately is an incoherent approach to teaching reading. It needs to be revised; and it might be better not to use it at all. One role states can play is to take the guesswork out of the equation and provide districts with a list of vetted core curricula that are aligned with the science of reading. With many products on the market, this guidance would be a value-add, while still giving local choice, and helping to ensure teachers use high-quality instructional materials.

Recommendations:

- Require districts to select vetted literacy curriculum materials and make those decisions public (core, intervention, supplemental materials). Instead of trying to revise a flawed model curriculum, the state should require ODE to establish (preferably using an external partner) a list of high-quality core curriculum, supplemental, and intervention materials aligned with the science of reading, which districts would be required to use. (Colorado provides a strong example of where to start.)[31] The state should also establish clear requirements for annual reporting to the state, families, and the public about the curricula, intervention and supplemental materials in use. The policy should indicate clear next steps for state intervention if districts do not comply in a given timeframe, while also directing ODE to develop a supportive strategy to help districts transition to new instructional materials and provide state funds to support the purchase of new materials.

Led by Governor DeWine, legislation (House Bill 33) is pending that would require the ODE to establish a list of high-quality core curricula and instructional materials and a list of evidence-based reading intervention programs that are aligned with the science of reading. This ambitious legislation is to be commended. However, there are no requirements in the bill at the time of this publication for districts to publicly disclose what curriculum schools decide to use or for monitoring progress of curriculum adoption, or any described consequences for using poor quality, misaligned curricula. The consequences could include withholding a modest portion of state funding (something that Arkansas permits). While consequences would exist as a last resort, it would signal the importance and urgency of transitioning to instructional materials aligned with the science of reading. The curriculum materials teachers use are critically important in teaching kids to read; although these recommendations may seem heavy-handed, the choice of curriculum is up to the district—and there are many available high-quality reading curricula available; yet given the reading crisis in Ohio and the importance of all students being literate, the state cannot afford to simply trust that districts will make good choices. It’s the right of the public to know whether (or not) Ohio’s children and Ohio’s teachers have access to the best curriculum materials aligned to the science.

Professional development

The Ohio Department of Education explicitly states that teacher professional development is a priority in its “Raise Literacy Achievement” plan. Specifically, one goal of that plan is to “sharpen educators’ abilities to implement reading instruction and intervention that is aligned to the science of reading and is culturally responsive.”[38] Further, as part of Ohio’s third-grade reading guarantee law, the State Board has adopted reading competencies[39] and dictated that they guide all professional development. These actions place professional learning at the heart of building teacher capacity to implement scientifically based reading instruction. Yet much more could (and should) be done to improve professional development for current teachers across the state.

Recommendations:

- Provide clear expectations for professional development and dedicate funds to train in-service teachers. Several states (Mississippi, Texas, and North Carolina) are directly providing the training, or directing funding to districts to implement training, to build current teachers’ capacity to teach scientifically based reading instruction. Statewide efforts such as these create greater coherence and common language across the state, which is one of the benefits cited by Mississippi during its implementation, which was the only state to show meaningful gains in reading on NAEP before the pandemic. In many states, training is also supported by literacy coaches, a cadre of experts hired and managed by the state, who provide more intensive, ongoing, hands-on professional development.

House Bill 33 sets aside significant funds for teacher training and literacy coaches. These resources are critical to support teachers and leaders in Ohio’s transition to more effective instructional approaches. Ohio should go further, and more explicitly define exactly what the training would entail and ensure there are approval mechanisms in place. To strengthen the legislation, state lawmakers should add language that requires the training to be approved by the Ohio Department of Education to ensure it covers the critical knowledge and skills aligned to the reading science and structured literacy approach.

- Evaluate progress. The state should establish parameters and set aside funding to conduct an evaluation of implementation and return on investment of HB33 and/or prior reading initiatives or current professional development offerings. Studying implementation is often forgotten, but it is incredibly valuable over time to determine success and where to continue or stop investing resources.

Conclusion

The research is clear on how reading develops and on the best methods to teach beginners how to read. In fact, there’s no realm within K-12 schooling that comes close to early reading, in the clarity of the evidence as to what works and what doesn’t.

All teachers of students in the early grades deserve access to this knowledge and skills, so they can become effective instructors. All children deserve to be taught using scientifically based methods so that they can become strong lifelong readers. Right now, only 4 in 10 of Ohio’s fourth graders read proficiently. The future for children, and for the whole state of Ohio, is bleak if we do not change the trajectory. Ohio’s prosperity–both in economic terms and in well-being and happiness–depends on literacy of all its members. It is not an understatement to say the future of Ohio depends on our actions now.

The first step to achieving these goals is strong teacher preparation. But teacher preparation in Ohio today is uneven at best. On average, elementary programs only cover three of the five components of the science of reading. While nine programs earn an A, serving as exemplars for others, many more programs fail to adequately address multiple components. Unfortunately, Ohio is also home to preparation programs that train teachers in multiple practices that are contrary to the evidence base.

Based on this review of Ohio programs, state policymakers need to take steps to ensure that all teachers are well-trained in the science of reading. They also need to support current in-service teachers so they have up-to-date knowledge and skills and are able to implement effective literacy instruction.

While standards are important, what we have learned over the past decade is that having standards is not enough to drive sustained change, and the state must play an active role to achieve success at scale. States such as Colorado and Mississippi have shown that a coherent, sustained, and comprehensive approach at the state level can yield positive results. Ohio leaders and policymakers must ensure that teacher preparation programs develop an aspiring teacher’s knowledge and skills aligned with the science of reading. Otherwise, we’ll keep spending resources to re-train teachers, when those dollars could be used in a number of other critical areas to support students. To support sustained implementation, Ohio should also provide school districts with a list of core curriculum that is aligned with the reading science, then require districts to select from the list. This saves time and capacity for school districts who are busy running daily operations while ensuring materials in use are of high- quality and allowing choice at the local level. Rigorous professional development should strengthen teachers’ ability to implement effective instruction as well.

Ohio already has a strong foundation in literacy. Some of America’s best teacher preparation programs—when it comes to reading science—are located in the Buckeye State. Let’s learn from them and use state policy reforms to drive sustained instructional change. There is no time to lose. Ohio students are depending on us to open doors to a more successful future – and the state’s own future depends on it.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Heather Peske, Shannon Holston, and the NCTQ team for authoring this fine report on a topic of significant importance for Ohio schools. On the Fordham team, my deepest thanks to Michael J. Petrilli, Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Jessica Poiner for providing thoughtful feedback during the drafting process. Special thanks also to Fordham’s Jeff Murray who provided support in report production and dissemination. Nathan Leibowitz copy-edited the report and Nat Bauer created the design.

Aaron Churchill

Ohio Research Director

Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Endnotes

[6] Tamborini, C. R., Kim, C., and Sakamoto, A. “Education and lifetime earnings in the United States.” Demography, 52(4) (2015): 1383-1407.

[11] Foorman, B. et al. “Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008).” Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, 2016.

[15] Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment

[16] For example, the report states that in its review of research since 2000 (when the National Reading Panel report was released), the practice guide “finds new evidence supporting instruction in alphabetics, fluency, and vocabulary, as well as new evidence supporting instruction in additional skills.” The practice guide notes multiple findings reinforcing the results of the National Reading Panel study. Foorman, B. et al. “Foundational Skills to Support Reading for Understanding in Kindergarten through 3rd Grade.” Educator’s Practice Guide. NCEE 2016-4008. What Works Clearinghouse. 2016.

[19] Savage, R. et al. “A randomized controlled trial study of the ABRACADABRA reading intervention program in grade 1.” Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), (2009): 590.

[20] Hempenstall, K. “The three-cueing model: Down for the count?” Education News. 2006

[21] Petscher, Y. et al. “How the science of reading informs 21st century education.” Reading Research Quarterly, 55, (2020): S267- S282.

[22] Foorman, B. et al. Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten.

[23] Hindman, A. H. et al. “Bringing the science of reading to preservice elementary teachers: Tools that bridge research and practice.” Reading Research Quarterly, 55, (2020): S197-S206; Hudson, A. K. et al. “Elementary teachers’ knowledge of foundational literacy skills: A critical piece of the puzzle in the science of reading.” Reading Research Quarterly, 56, (2021): S287-S315.

[26] Ohio Administrative Code 3333-1-05 requires evidence of faculty credentials, coursework, assessments, and experiences.

[29] Salinger, T., et al. “Study of teacher preparation in early reading instruction.” Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2010; Moats, L. “Knowledge foundations for teaching reading and spelling.” Reading and Writing, 22(4), (2009): 379-399; Lane, H. B. et al. “Teacher knowledge about reading fluency and indicators of students’ fluency growth in reading first schools.” Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25(1), (2008): 57-86; Washburn, E. K., Joshi, R. M., & Binks-Cantrell, E. S. “Teacher knowledge of basic language concepts and dyslexia.” Dyslexia, 17(2), (2011): 165-183; Cheesman, E. A. et al. “First-year teacher knowledge of phonemic awareness and its instruction.” Teacher Education and Special Education, 32(3), (2009): 270-289; Rutherford, A., Carter, L., Riley, M., & Platt, S. “Content knowledge reading assessment: A policy change impacting elementary education candidates’ preparation.” Research in Higher Education Journal, 33, (2017).

[30] Specifically, multiple grade-level curriculum reference or directly encourage educators to use resources in balanced literacy, including Lucy Calkins’ Reading Workshop, and texts by Fountas & Pinnell.

[32] U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse. Beginning Reading intervention report: Reading Recovery®. 2013.

[33] The i3, or Investing in Innovation Fund was established as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009. The program provided competitive grants to local education agencies and nonprofits with a record of improving student achievement. Scale-up grants were awarded to “mature organizations” that had to “demonstrate organizational capacity to scale their interventions broadly.” Boulay, B. et al. “The Investing in Innovation Fund: Summary of 67 Evaluations: Final Report (NCEE 2018-4013).” Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: 2018.

[35] May, H. et al. READING RECOVERY.

[36] Nicholson, T. “Do children read words better in context or in lists? A classic study revisited.” Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4), (1991): 444.