Nearly three months have passed since the third round of ESSER funding was signed into law as part of the American Rescue Plan (ARP). These dollars can be used for almost anything under the education sun, and most of them will flow directly to districts, but the limited set aside for states merits attention if only for the staggering scale of Uncle Sam’s total outlay. Indeed, ARP alone provides $12 billion to state education agencies—a quarter of which can be used at their own discretion. To put that into context, Race to the Top was a paltry $4.35 billion, and with plenty of strings attached. For better or worse, no such conditions exist this time around, and a quick scan of plans thus far reveals a strong inclination among states to spread that $12 billion so thinly as to accommodate a potpourri of political and substantive demands.

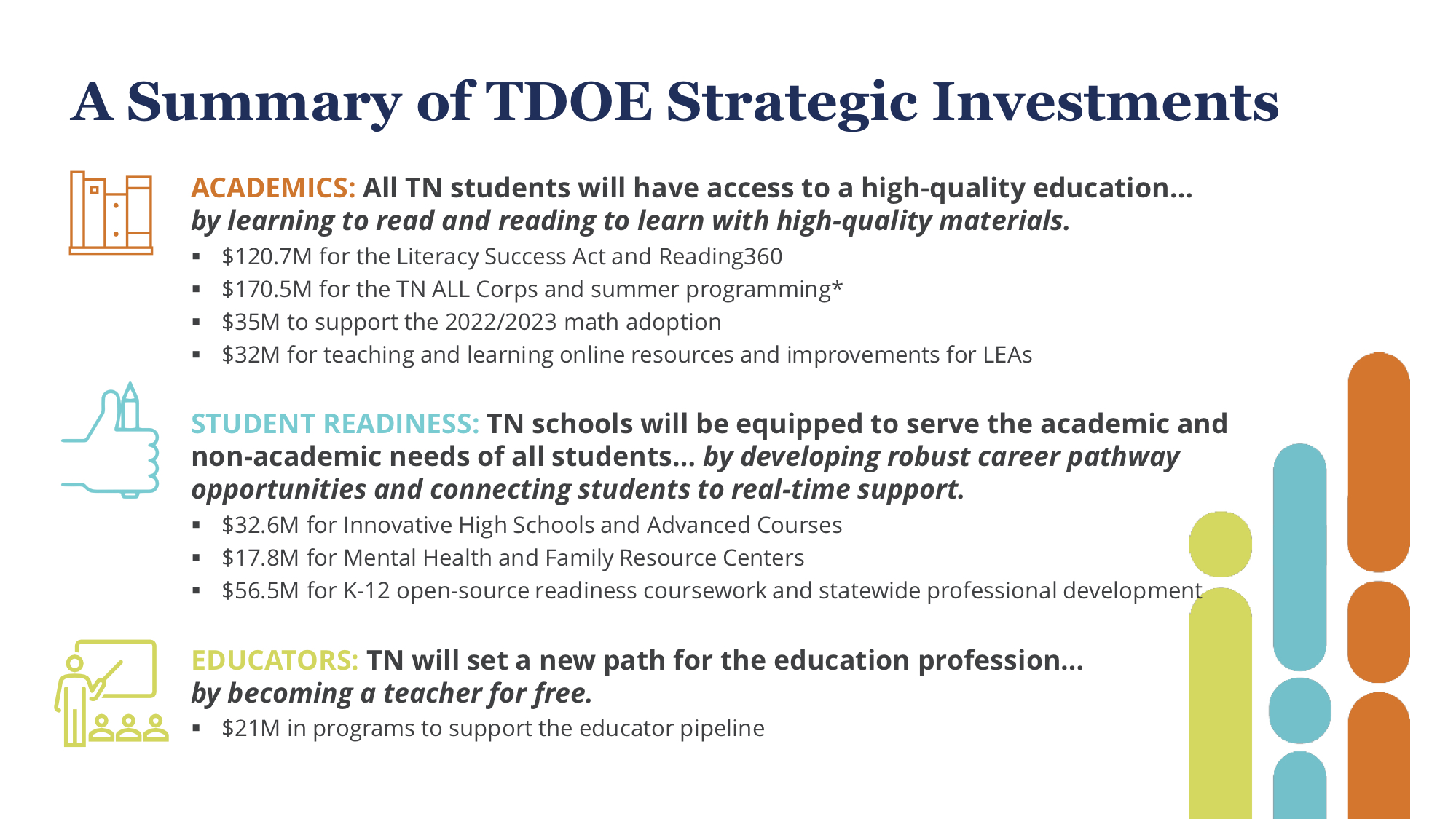

History and experience suggest that we’ll regret that decision down the road, especially if there’s little impact on student learning to show for it. But Tennessee’s smart strategy for spending offers reason for encouragement. Its plan for the state’s portion of the federal stimulus takes square aim at accelerating student achievement by investing in three key areas: academics, student readiness, and professional learning—including $120.7 million for reading and $170.5 million for tutoring and summer programming (see chart below). Tennessee’s approach is very much in line with Fordham’s model recovery plan, The Acceleration Imperative, in that the provision of “extras” like tutoring and mental health supports accompanies the improvement of core instructional programs via high-quality curricula and curriculum-based professional development.

Source: Tennessee Department of Education.

Of course, a plan is only as good as the leaders charged with seeing it through (more on that below), but the greater risk for states newly awash in cash is the lack of planning. To wit, Tennessee will have five times the amount it received from Race to the Top, and just half the time to spend it. Fortunately, it’s been ahead of the curve in figuring out how to leverage the extraordinary bonanza. Governor Bill Lee kicked things off in January when he called for a special legislative session focused on education recovery. State lawmakers rose to the challenge and passed the Tennessee Learning Loss Remediation and Student Acceleration Act, which requires districts and schools to implement three extended learning programs, called “camps,” designed to get students back on track.

At the same time, Lee and his highly capable education commissioner, Penny Schwinn, recognized that the extra help provided by these camps would not replace what students get from schools’ core programs. This understanding is reflected in another piece of stellar legislation passed during the special session, the Tennessee Literacy Success Act, which incentivizes schools and teachers to focus on early childhood literacy. Notably, Tennessee now requires its forty-four teacher prep programs to provide training on sound literacy practices, and all of the Volunteer State’s 147 districts must adopt a phonics-based approach to reading instruction. Thus unapologetically clear-eyed view of reading starts at the very top, a posture that many education observers living elsewhere can only envy.

What’s more, Tennessee’s spending plan builds upon Schwinn’s “Best for All” blueprint, which was developed long before Covid-19 extended its claws. Rather than starting from scratch, Schwinn reaffirmed the three main priorities in her strategic plan, and appropriately reframed a focus on the “whole child” to a post-pandemic emphasis upon “student readiness.” Taken together, Tennessee has eschewed a “peanut butter approach” to spending—spreading a little bit everywhere in an attempt to satisfy everyone—opting instead to follow the sage advice from former governor Phil Bredesen: “A hundred dollars spent to address a problem is often more effective than one dollar spent a hundred times.”

Tennessee’s plan follows the science not only on reading, but also for large-scale assessments. Although not strictly a part of the state’s spending plan, Tennessee’s General Assembly, to its credit, stood firm on the administration of state exams this spring. Last week, I had the opportunity to speak with Schwinn, along with two of her colleagues, on how Tennessee plans to use assessment data to guide its education recovery efforts. (You can watch the entire conversation here). Schwinn minced no words in underscoring the importance of measurement as part of the state’s overall strategy:

We’ve got to know how our kids are doing... We need to be able to have longitudinal data over time. We need to be able to see how our kids did five years ago, three years ago, this year, and then moving forward to know the impact of the pandemic. We need to be able to really emphasize how our investments with this new federal funding are aligned to the needs of the students in our state in this moment. And that has to be on a consistent measure.

It’s a compelling argument, and one that raises the question of how any state can have a viable plan for recovery absent the information provided by statewide testing.

With summer upon us, Tennessee and its neighbors will soon be submitting their ARP ESSER state plans to the federal government. Preparations for next fall are kicking into high gear in schools and systems nationwide as part of the broader effort to address the enormous challenges faced by students, educators, and families during the last fifteen months. Much uncertainty remains, but policymakers and practitioners would do well to follow Tennessee’s lead and seize this rare opportunity for real change—by pausing to set clear goals and figuring out how to make the most of this one-time federal windfall.