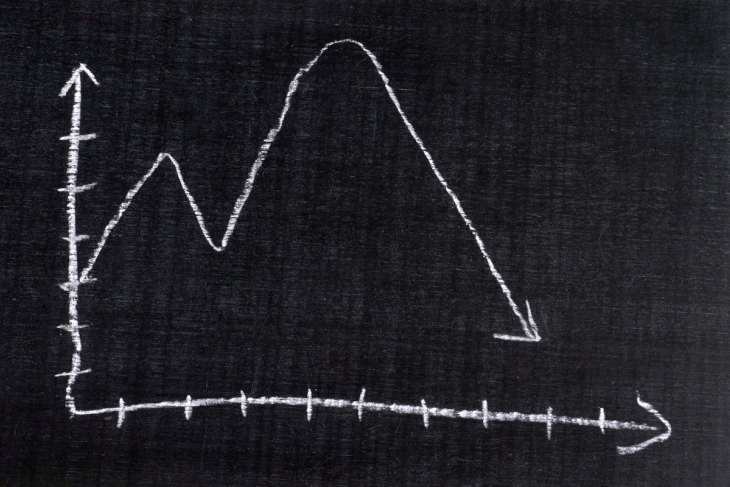

I haven’t seen the data myself, but let me predict that the forthcoming results from the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)—due out on January 29—will be bad, bad, bad. The term we may hear a lot is that “the bottom is falling out,” if the scores for low-performing students in particular continue to plummet.

While deeply disappointing, it wouldn’t be surprising, given that we’ve seen the same pattern recently on TIMSS, PIAAC, i-Ready, MAP, and state assessment results.

It’s also predictable. Indeed, in October 2021 I forecast that NAEP scores “will be depressed through at least the early 2030s.” As I wrote back then:

Think of today’s first graders, who spent last year doing “remote kindergarten.” Many of those kids likely learned next to nothing, meaning they entered first grade a year behind. For our neediest students, who tend to enter kindergarten years behind in normal times, the challenge is even greater....

So our first grader is probably going to fall further behind this year, too. [And] in three years, when he takes the fourth-grade NAEP, these scars are going to show. And they will still be apparent seven years from now, when he sits for the eighth-grade NAEP, and eleven years from now, when he takes the twelfth-grade NAEP. (If he makes it to twelfth grade, that is.)

Gulp. I won’t be happy if I’m right about this. But allow me to explain my thinking.

Here’s the first key point: When we say that test scores like those from NAEP are declining, we mean that the most recent cohort of fourth and eighth graders are posting lower achievement than their older peers—their older brothers and sisters, so to speak—did at the same age. We’re not saying that Johnny is doing worse than he did two years ago, but that he scored lower than his older brother Jimmy did back then. Keep that thought: It’s about cohorts.

Second, we have to remember that test scores don’t just reflect what has happened to a student in the most recent school year, but everything that’s happened in the child’s life to date. All the health and nutrition and stimulation they did or did not get as babies and toddlers, their early childhood experiences, their school experiences from kindergarten into the fourth (or eighth) grade. It all matters.

We might ask ourselves: How would we expect different cohorts of kids to be impacted by the pandemic and lengthy school closures?

I would posit that the cohort that might be harmed the most—at least in terms of academics—would be the one that was in kindergarten when the Covid pandemic struck. Especially students in that cohort who didn’t return to in-person learning for much or any of first grade because they attended schools in deep-blue cities and suburbs that were shuttered the longest.

And guess what: That’s the cohort of kids who were fourth graders in 2024. I won’t be surprised, therefore, if those fourth-grade scores look especially bad.

I hope that 2024’s eighth graders fared at least a little bit better, given that they were in the fourth and fifth grades during the pandemic shutdowns, which is not great, but at least most already knew how to read before their education world was upended. Again, I haven’t seen the results, so we’ll see.

Now, if this comes to pass, we shouldn’t let schools off the hook for the terrible trends. As Laura LoGerfo reminded us last month, scores, especially for low-performing students, were already trending downward before Covid, perhaps reflecting the backing away from accountability and other reforms in the 2010s. And of course, after the pandemic struck, systems received $190 billion in federal funding to get their schools open and to address learning loss; studies indicate that those funds helped but had a very modest impact. Some districts squandered the money. Others tried worthwhile tactics, like high-dosage tutoring, but struggled with implementation. Whatever they did (or didn’t do), it wasn’t enough.

One thing nobody tried, to my knowledge, was to admit that Zoom school was next to worthless and have everyone repeat the grade they missed while home for a year. If the kids who were fourth graders in 2024 had been given the chance for a do-over of first grade, with a real live teacher in a real live classroom, mastering their early reading and math skills, I suspect we would be in a much better place today. (It’s not too late for schools to embrace something like this! Especially since we know, from i-Ready and MAP data, that kids are still entering kindergarten further behind academically than their pre-pandemic peers.)

—

In many respects, the United States has made a remarkable recovery from the Covid pandemic. Unemployment is down. Economic growth is up. Wages are rising, especially at the low end. Crime has fallen. Even the obesity epidemic has appeared to plateau.

But all that positive news can’t mask the reality of what the pandemic did to our children. A generation of Americans is growing up with academic scars that will last a lifetime. And we’re all just letting it happen.