- Parents, demonstrating more practical wisdom than activists and policymakers, are in favor of more career-oriented programs in high school. —City Journal

- Miami Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, with a strong record on accountability and school improvement, was selected to lead the Los Angeles school district. Can he replicate his success? —The 74

- “We have all of this talent just sitting there,” says Jonathan Plucker about the state of gifted education in America. “And the child isn’t benefiting from their own skills. That is a massive societal failure. We simply have to do better.” —The 74

- A new report shows widening inequities in schools’ pandemic recovery, with some students in majority-Black schools now trailing White peers by a full twelve months of learning. —McKinsey

- A teacher unionization effort is underway at Menlo Park Academy, the only Ohio charter school specifically for gifted students. You might figure that all the smarty-pantses there could figure out how to manage it without kerfuffling, but it appears you’d be wrong. Side note: Lawyers seem to be, as ever, cleverer than everyone else involved. (Cleveland.com, 12/14/21)

- Speaking of unusual charter school happenings (were we?), I believe that this story marks the first documented effort to open a new school in an area of Ohio which was previously off-limits. Specifically: that bougiest of all bougie Columbus suburbs, New Albany. You may recall that the most recent state budget included a provision removing geographic restrictions on charter location. And if all goes well with the various zoning board and city council hoops, Cornerstone Academy (with two buildings currently bursting at the seams, so they say) will open a 6-12 school in New Albany to serve its growing enrollment. (ThisWeek News, 12/8/21)

- Have some sympathy for current Youngstown schools CEO Justin Jennings, whose bid to leave the district for greener pastures in Akron City Schools was tabled Monday night with no action taken. The good folks at Vindy.com take pains to reiterate that the elected board has had a "contentious relationship" with him over the years. And while the chair of the Youngstown ADC thinks Jennings is the bee's knees, I can't imagine this helps too much with his chances anywhere in Ohio...and probably beyond. (Vindy.com, 12/15/21)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Several people I admire have recently passed away (Bob Dole, Colin Powell, Fred Hiatt, Stephen Sondheim…), but the only one in that group who was also a close friend is Denis Doyle, who died at eighty-one on December 2 in Los Angeles, his home in recent years.

Several people I admire have recently passed away (Bob Dole, Colin Powell, Fred Hiatt, Stephen Sondheim…), but the only one in that group who was also a close friend is Denis Doyle, who died at eighty-one on December 2 in Los Angeles, his home in recent years.

Denis and his late wife Gloria returned to their native state late in life to be near their children and grandchildren and because the indomitable Gloria needed more medical attention and personal help. It was the right move, and they were spectacularly well looked after as Gloria grew weaker and Denis acquired health challenges of his own.

I had the opportunity to visit a couple of times, including shortly before the Covid-19 plague shut everyone down. Denis was physically diminished but sharp, affable and curious as ever. Our real relationship, though, was in Washington, where for decades Denis and Gloria and Renu and I lived a couple of miles apart. It was both a professional and social connection. Our kids attended the same school. We dined together a hundred times. We had many mutual friends. Renu was occasionally able to offer medical suggestions, and I lapped up the recipes in Gloria’s self-published cookbooks.

Gloria Revilla Doyle, it must be noted, was one of the most remarkable people I have known. Despite a degenerative situation that left her a quadriplegic for decades, she was so much more than plucky and determined. She was regal and commanding, inquisitive, generous, and kindly, pursuing a wide range of interests with a wide range of friends—and expertly hosting many of us—with nary a “woe is me,” at least none that we ever heard.

And Denis was always there, even while maintaining his own busy and productive professional life, unfailingly supportive, patient, loving, and accommodating, both in suburban D.C. and later in the City of Angels.

Denis’s professional life was, of course, spent in the education realm, where we first intersected and bonded, not just because we agreed on so much, but also because we stimulated each other and on multiple occasions were able to collaborate, including co-authored pieces that sometimes gored ungrateful oxen.

Denis started his career as a staffer to the California legislature, then came to Washington to work at the Office of Economic Opportunity and National Institute of Education (antecedent to IES), where he played a large role in early school-voucher experiments. Post-government, Denis was connected to several eminent think tanks and was a prolific author, pundit, and scholar under their auspices and as an independent consultant. He remained passionate about school choice, particularly as a necessary strategy to help needy kids otherwise stuck in dire schools. He hated the hypocrisy of those who opposed choice for others while availing themselves of it for their own kids. But he was no “silver bullet” reformer. He had plenty of ammunition—and plenty of targets. He served on the National Commission on Time and Learning. While at AEI, he (and Terry Hartle) wrote incisively about the strengths and weaknesses of state education agencies. He penned a trenchant comparison of the U.S. and Japanese education systems. Possibly his most influential work, coauthored with the late David Kearns, was Winning the Brain Race: A Bold Plan to Make Our Schools Competitive.

Later in his career, Denis and a couple of colleagues launched a successful educational technology firm called SchoolNet.

As Andy Rotherham wrote of Denis, “A few things stand out. First, his mind. You run into smart people in this sector all the time, and then you run into *smart* people in this sector. He was the latter. A real intellect, polymath, and curious person. Second, he was funny. He was kind, but he was hilarious.”

His influence was felt far and wide, not just through his scholarship and commentary, but also through his impact on others. As Andy noted, “[U]pon his passing, it was noteworthy the number of people who said things like, ‘a real mentor to me.’” And as Leslye Arsht and Sue Pimentel wrote, “Denis brought a unique mix of expertise and common sense, confidence and curiosity, and understanding and good humor to charged and complex arenas. He was one of a kind and will be missed.”

Denis was fun, too. A teller of stories, a connoisseur of fine food and drink, a gracious and open-handed host, a genial companion, and the owner of a grand sense of humor. It would have been hard not to be his friend.

I’m privileged to have known and worked with him. But more than that, I loved the guy.

The funding system for early childhood education envisioned in Build Back Better is far superior to the one we have now. But as always in public policy, the transition from one condition to another is fraught with risks. In this case, one risk that has been identified is that the middle class will get squeezed as the program rolls out because supercharging the subsidies for low-income families when supply is limited will crowd out affordable opportunities for the middle class.

To assess this risk, it’s important to understand how the market for child care works. Families seek child care on the open market, and low-income families can receive a subsidy for some portion of their costs. But the reimbursement they receive isn’t closely tied to the actual cost of care, or to their family income. States tend to spread the money thinly to try to reach as many families as possible, which then leaves families having to bear significant child care expenses—even when they’re receiving public subsidies. And in practice, many families who are eligible for subsidies don’t even receive them.

Build Back Better would address these challenges in two major ways. First, it would change how states calculate the cost of quality to include adequate compensation for child care professionals and then require states to tie reimbursement to those costs. Second, it would cap the amount of money families would have to provide to cover child care costs; families with incomes over 150 percent of the poverty level would pay 7 percent of their income, and families with lower incomes would pay a lower percentage.

In general, the bill’s rollout approach—which prioritizes the needs of the lowest-income families—makes sense. In the child care market, the families with the most money are the ones most likely to find the services they want. Build Back Better provides support for lower-income families so they can compete for services, and it increases the odds that providers will find it worthwhile to offer services in neighborhoods that are currently “child care deserts.”

But there is a risk that the middle class will get squeezed. If workers in subsidized programs start receiving dramatically higher wages, that could drive up costs for all child care programs, given a limited supply. If middle-class families can’t compete with either the wealthy or the subsidized, it will leave them in a bind.

Ultimately, that risk is the price of having a transition like the one the bill contemplates. Leaving the current system in place would be a terrible mistake, and so some kind of plan for change is needed. And the bill’s focus on prioritizing low-income families is directionally correct.

So states will need to pay attention to the impact of their policies to make sure their policy choices are not overheating the market. For example, states have some flexibility to set reimbursement rates. Even more important, they have some flexibility when it comes to the rollout of eligibility; while states are expected to prioritize children with the greatest need, they have control over how rapidly the program expands to serve additional children.

Because of these flexibilities, it’s by no means inevitable that states will adversely impact the child care market for middle-class families as they implement new policies regarding costs, quality, salaries, and eligibility. But it’s not inevitable that they won’t, either. So it’s important for states to have good information about the impact their decisions are making, and the ability to correct course if state policy choices on reimbursement and eligibility are sending the market in an unhealthy direction.

Right now, states don’t even know how changes in the child care market are affecting the middle class. Indeed, most states don’t have good enough data to track supply and demand in the market in a timely way. Without that information, states can’t track the impact of their policy decisions, and would come dangerously close to flying blind. At this point, most states have at best a rudimentary understanding of how middle-class families are experiencing the child care market—let alone how they might be impacted by different choices in the implementation of Build Back Better.

No state is going to intentionally squeeze middle-class families out of child care. But federal law is a very broad sword, and without the right management systems, states could inadvertently end up swinging it in the wrong place. Ideally, states will rise to meet the challenge by collecting better data—and then using that data to adjust reimbursement and eligibility policies in a way that maximizes access for low-income families, while avoiding spiraling prices for families who aren’t getting the subsidy. And the federal government will have to accept states’ needs to make occasional course-corrections in management that are in keeping with Build Back Better’s direction, even if they stray mildly from what they’ve committed to in their initial plans.

In practice, the heaviest lift may be helping states and communities build up the capacity to manage effectively whatever flexibility is on offer, which is particularly important given the seismic shifts that are about to occur. Fortunately, building data and analytic capacity is an allowable use of federal funds, and should be one of the first priorities for states when the money comes through. Build Back Better is a major opportunity for states and communities to create analytic systems that help them adjust on the fly. Some states and communities are already working to build that kind of capacity, using funds from the federal Preschool Development Grants to get a running start. But there is a long way to go.

Early childhood is a complicated system, and the Build Back Better law won’t exactly reduce its complexity. It will, however, support states in achieving important goals. There’s no question that implementing the law will be a challenge. But the current system isn’t working for children and families. Build Back Better is a chance for states to make the break and reset that the early childhood system sorely needs.

- It appears likely that current district CEO Justin Jennings will not be superintendent of Youngstown City Schools when the elected school board regains control. (Pretty sure someone in these very Bites predicted this several weeks ago.) But it's not for the reason you might think. He is, according to this piece, being considered for assistant supe in Akron City Schools during this evening’s school board meeting there.

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

The early childhood field has long recognized the need to transform its workforce—in meaningful part because early educators are paid so poorly. To address this challenge, the Build Back Better legislation significantly expands the federal investment in both pre-K and child care, including major changes to how early educators are paid—and in the case of pre-K, the requirements for their qualifications. Contrary to the critiques that have been leveled by some observers, all of these changes should help these important programs achieve their goals: for pre-K, improved educational outcomes, and for child care, helping parents participate in the workforce while providing a high-quality experience for children.

Improvements to state pre-K programs

Two of the most significant requirements of the pre-K initiative in Build Back Better are the requirement that lead teachers have bachelor’s degrees in early childhood education and the requirement that their pay be comparable to that of elementary school staff with similar qualifications.

Improving instructional quality should be a major goal of preschool expansion. In the federally-funded Head Start program, ratings for “Instructional Support” are lower than for “Emotional Support” or “Classroom Organization.” There is strong evidence supporting the idea that improved teacher education leads to better results, even if the research on the impact of bachelor’s degrees is mixed.

In practice, improving the quality of instruction requires more than just mandating BA degrees—it requires paying teachers more. Over the years, early childhood programs have had a hard time retaining teachers with BA degrees, in part because the pay and benefits in K–12 are so much better. In 2020, the median salary for preschool teachers (with or without a BA) was $31,930; for kindergarten and elementary teachers, it was $60,660. For pre-K teachers who have the qualification to obtain a K–12 job, the temptation of the higher salary is ever-present.

The short-term impact of a BA requirement should be manageable, for at least two reasons. First, most state pre-K programs already require teachers to have a BA. Second, Build Back Better allows exemptions for teachers who have been actively teaching pre-K without a BA in three of the five years prior to the law’s passage.

While the necessary supply of high-quality pre-K teachers won’t materialize overnight, over time an increase in average salaries should drive the market from the demand side—which is the only way to do it. States can’t force institutions of higher education to produce more teachers with early childhood degrees—or force more students to take a serious interest in early childhood education. But if those degrees become more valuable, both individuals and institutions will adjust their behavior. To wit, in the last twenty-five years, the percentage of college graduates receiving bachelor’s degrees in education has dropped more than 50 percent, while the percentage of graduates with bachelor’s degrees in computer science has more than doubled. That’s a sign that the market has an impact, even if it takes a while.

Interestingly for choice advocates, increased spending on pre-K teacher pay could represent a major subsidy for private providers. Pre-K systems in many states are “mixed delivery,” meaning that both public and private providers deliver equivalent services. Build Back Better requires that states take a mixed delivery approach. Historically, private providers have had a hard time competing with public schools when it comes to pre-K teacher salaries because school districts often include pre-K teachers in their salary schedule. Accordingly, the salary comparability provisions of Build Back Better should end up unlocking more support for the salaries of teachers at participating private pre-K programs. Private providers are understandably anxious about the potential impact of Build Back Better, but the legislation should actually improve the odds that private pre-K providers can compete for talent.

Improvements to child care

Child care is expensive primarily because federal and state safety requirements require relatively low ratios of adults to children—especially for infants and toddlers. On average, the parents of young children are earlier in their career than the parents of college students, which means they tend to have lower incomes. This means they can end up spending a high percentage of their salaries on child care. And yet, despite these costs, child care staff are still receiving very low wages. Pre-pandemic, more than half of child care workers in the United States qualified for public income supports.

Child care funding works very differently than funding for public schools. Public schools receive an annual budget, and the school’s enrollment, past or projected, is typically a major factor in its funding. The school is a public good that is available to any child eligible to enroll.

In contrast, under the Child Care and Development Block Grant, parents are provided with subsidies, often in the form of vouchers. The parents purchase services on the open market and are reimbursed for a portion of their expenses by public funds. Providers are typically paid based on attendance rather than enrollment, so if a few kids are sick for a week, the provider’s budget may be out of whack all of a sudden. Compared to school funding, child care funding is unpredictable and unstable.

It’s also inadequate. Under current law, the levels at which parents are reimbursed aren’t tightly tied to either family resource levels or the actual cost of quality care. Consequently, even with government subsidies, low-income families often face crippling costs. Build Back Better would address this disconnect by requiring states to certify that their payment rates will meet the actual cost of care, including providing for adequate salaries. It would also cap family copayments at no more than 7 percent of household income for families with incomes over 150 percent of the federal poverty level.

Like pre-K, child care has a significant impact on the economy and workforce. Without good child care, parents simply won’t go back to work. And at a time when unemployment is at all-time lows, subsidizing child care is an important way to get more parents off the sidelines.

Moreover, from a child development standpoint, continuity of care is an important value. Young children develop best when they can build relationships over time. If child care providers are underpaid, it increases the odds that they will leave for some higher-paying job, which can be a setback for kids. And because of low pay, turnover is a significant problem among child care staff.

Interestingly, the simultaneous rollout of universal pre-K might exacerbate this problem. If salaries increase for pre-K teachers, and states create pathways for child care professionals to get credentials, then many child care professionals will leave to become pre-K teachers—unless the salaries of child care workers also increase.

But pre-K is far from the only competition drawing away child care professionals. Several years before the pandemic, I was visiting one of the best-funded early childhood centers in the country. Unlike most child care centers, it leveraged multiple public funding streams and had ample philanthropic support. And yet the center was still unable to compete for staff with Uber or Lyft. Center staff would start driving in the evenings to make a little extra money, and then realize that, if they just drove all day, they’d increase their income. So they would.

To solve this problem, there needs to be enough money in the child care system to ensure that (1) parents can afford child care, and (2) child care providers can afford to stay in their jobs. Direct public subsidies will help on both fronts. And, as with pre-K, it will be important for states to cultivate a diverse delivery system—and to provide support to parents who are navigating that system.

But of course, a fully-formed system will take years to build. During those transitional years, there will also be real risks associated with implementation, including the possibility that middle class families will get squeezed and be unable to afford child care. But there are effective ways for the federal government and states to address such concerns. And the existence of these challenges doesn’t change that fact that Build Back Better would improve the ways America cares for—and educates—our young children.

In early November, Scott DiMauro, the President of the Ohio Education Association, went on the attack against public charter schools. In a piece in the Ohio Capital Journal, he analyzed report card data and supposedly found some “seriously alarming” results for school choice programs. But as is the case with several other anti-choice pieces that have been published over the last few years, his analysis is misleading and inaccurate. Let’s take a look at two of the most egregious statements.

Statement One: “Charter advocates often complain about comparing all school districts’ performance with charters, but last year, 606 out of 612 public school districts in the state lost scarce resources to charter schools.”

Charter advocates “complain” about this comparison because it’s purposefully misleading. According to the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), 114,374 students were enrolled in one of Ohio’s 315 charter schools during the 2020–21 school year. But nearly 95 percent of students who attend brick-and-mortar charter schools live in the state’s fifty-five urban school districts. That’s why we at Fordham focus so heavily on comparisons between urban charter schools and urban district schools.

Of course, brick-and-mortar schools aren’t the only charters in Ohio. The state is also home to fifteen virtual charters known as e-schools, and they enroll over 34,000 students. Because e-schools offer classes online and aren’t tied to a physical location, they can and do serve students from all over the state. It’s e-schools that make it possible for charter critics to claim that over six hundred districts “lose” tax dollars to charters and justifies, at least in their minds, the comparison to statewide averages.

But making that claim without context is misleading because it overlooks the scale of the alleged impact. There’s a big difference between a few students transferring to charters and hundreds of students doing so. Charter critics know that. They know that the vast majority of charter students live in urban districts. They also know that, on average, the percentage of students in each district who attend online schools is very low. And yet they make the purposely misleading comparison anyway.

It’s also disingenuous to claim that districts have “lost scarce resources” to charters. In a student-centered funding system, no school—district, charter, private, or otherwise—is entitled to students and the per-pupil funding associated with them. And if districts aren’t entitled to funds, then it can’t be considered a “loss” when they don’t receive them. That would be akin to a childless person claiming that they “lost” funding when they weren’t awarded a child tax credit, or officials complaining they have “lost scarce resources” when a family moves to a neighboring district. Families have the right to choose where to send their children to school (despite what DiMauro and other choice critics believe), and schools should be allocated money based on students they actually teach, not students they could have taught. If a student opts to attend a charter school, the state money designated to educate that child should follow them to the school that’s doing the work of educating them. To do otherwise would be to prioritize systems—one specific system—over students. That’s exactly what DiMauro does when he focuses on the bogeyman of lost revenue rather than the question of what students and families need.

It’s also important to remember that schools are funded by state and local dollars. On average, 45 percent of elementary and secondary public school revenues are from local sources. For the most part, these dollars aren’t tied to student enrollment. When a child attends a charter or private school, districts still receive all the local dollars that families pay in taxes. That means that, on average, nearly half of district budgets are insulated from student enrollment losses. Charter and private schools can’t say the same. And all this doesn’t even account for federal funding, including hundreds of millions in Covid-relief dollars, or decades’ worth of growth in state school funding amounts. Overall, it’s hard to claim with a straight face that funding for school districts is “scarce.”

Statement Two: “Vouchers and charters take critical resources and weaken the public schools that serve the vast majority of Ohio’s children while delivering worse educational outcomes for our kids.”

We’ve already debunked the argument that school choice programs “take critical resources” from traditional public schools. And the assertion that public schools are “weaker” because of choice programs is an inaccurate read of the existing research. Various studies, from both Ohio and elsewhere, show that school choice programs don’t hurt district achievement or funding. That leaves the claim that vouchers and charters deliver worse educational outcomes for kids. Elsewhere in the piece, DiMauro calls them “poorer performing alternatives.” As evidence, he highlights post-pandemic drops in performance index scores at charter schools like KIPP in Columbus and the Breakthrough network in Cleveland.

There’s a lot to unpack here. For starters, the assertion that charters deliver worse educational outcomes for kids is mostly wrong. A rigorous analysis of Ohio data from 2015–16 through 2018–19 found that in grades 4–8, students in brick-and-mortar charters made significant gains on state math and ELA exams when compared to district students of similar backgrounds. Black students made particularly strong progress, as did both high and low achievers. In addition, students’ attendance rates increased and disciplinary incidents decreased when they attended a brick-and-mortar charter. That’s hardly “worse educational outcomes.”

Given that, how can DiMauro claim that choice programs are poorer performing alternatives? The answer is that he cherry-picked data from a Covid-disrupted school year to fit his narrative. First, he compared charter schools—which are largely located in Big Eight districts—to all districts in the state. As discussed earlier, this is a common tactic used by those who champion the establishment over the wishes of parents and children. It allows them to compare charter schools, where the majority of students are economically disadvantaged (nearly 80 percent) and children of color (64 percent), to districts where the majority of students are affluent and White. In the best of times, it’s a misleading comparison. But in the context of Covid-19 learning loss, it’s flat out irresponsible. It’s no secret that the pandemic hit low-income and minority families the hardest. If someone wanted to get an honest and accurate picture of charter school performance during this time, they wouldn’t compare the performance index scores of charters to all districts. Instead, they would compare charters and districts that teach similar student populations and therefore faced similar pandemic-related challenges.

But DiMauro didn’t just compare apples to oranges and declare that apples were better. He also ignored years’ worth of evidence. He focused solely on results from the 2020–21 school year, which was dominated by a pandemic. And that’s the most infuriating part of all this—the stunning hypocrisy. Teachers unions have spent the entirety of the pandemic talking about how difficult our new reality has been for schools. They repeatedly mention how hard educators are working, the laundry list of difficulties faced by students and staff, and how unfair it is to judge schools on typical academic performance standards when the current climate is anything but typical.

And they’re right. Schools, educators, and students do deserve compassion and patience, and it will take time to make up for learning loss. But why is that compassion and patience only afforded to certain students and families? Have charter and private schools not struggled with the same health and safety concerns, the same student engagement and absenteeism woes, and the same remote learning issues? Are charter and private school educators not also teaching in the midst of a pandemic? Are the social and economic impacts of a once-in-a-generation event like this somehow less stressful for students who are enrolled in a school choice program?

Look, no one is saying that the huge drops in performance index scores or the rise in chronic absenteeism at Ohio’s charter schools aren’t worrisome. In fact, I’m pretty sure if DiMauro picked up the phone and called the folks who work at these schools or the families of the students enrolled there, they’d say they’re just as worried about student learning loss as he supposedly is. But the fact that he’s chosen to pointedly ignore years’ worth of research that contradicts him, zero in on a single and atypical year, and lambaste schools he doesn’t like while calling for compassion and patience for others is truly galling.

The bottom line? When union representatives say they’re advocating for “our kids,” they clearly don’t mean all Ohio children. If they did, they wouldn’t prioritize funding systems over funding kids. They wouldn’t cherry-pick performance data to make themselves look better—because they’d recognize that working alongside choice programs can lead to huge benefits for kids and communities. And they certainly wouldn’t see a global health crisis that caused millions of deaths, forced millions of others out of work, and compelled schools to close their doors for nearly a year as an opportunity to score political points.

Litigating the past using the past

Despite having already moved along with its work to authorize the first charter schools in West Virginia, the creation of the Professional Charter School Board is the subject of a lawsuit filed by school choice opponents. They cite a state constitutional precedent from 1872 in their arguments; more details can be found here. The case likely will see no further action until the new year.

Fantastic opportunity for new facilities funding

This week, the Equitable Facilities Fund, a social-impact nonprofit that finances facilities for high-performing charter schools, announced a $500 million commitment to public charter schools across the country that are run by people of color. The plan will provide low-cost loans for school facilities to approximately 30 schools with leaders of color between 2022 and 2026.

Supreme Court case is one to watch

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments this week in the case of Carson v. Makin. At issue is whether a 1982 Maine law violates the First Amendment by excluding religious schools from the state’s “tuitioning system,” which pays for students to attend private schools. Among other potential outcomes, experts say that the case could open the door for religious charter schools depending on how the justices rule.

The view from Ohio

This week, the Ohio Senate passed SB 229 and sent it to Governor DeWine’s desk for signature. Among other provisions, the bill clarifies the means by which public schools in the state can offer remote and hybrid learning options for the remainder of the current school year. Full details of the bill can be found here.

*****

Did you know you can have every edition of the Ohio Charter News Weekly sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

- Another quiet news cycle to end the week. The Ohio Senate this week passed SB 229. What started out as a bill covering a number of pandemic-related education issues for the current school year grew into either an “omnibus” bill or simple “cleanup language”, depending on who you ask. Among the provisions: clarification of the means by which public schools in the state can offer remote and hybrid learning options for the remainder of the school year and another year of exemption for the retention requirements for the Third Grade Reading Guarantee. Full details of the bill can be found here. Governor DeWine is expected to sign it into law soon. (Gongwer Ohio, 12/8/21)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.

Way back in the pre-pandemic Before Times, one of America’s more consistent and pernicious long-term trends was the growing domination of so-called “superstar cities.” As Richard Florida explained it, a winner-take-all dynamic was allowing a handful of metropolitan areas to dominate the knowledge economy. San Francisco and Silicon Valley, Washington, D.C., New York City, Boston, Austin, Miami, the Research Triangle, and a handful of other leading metros were raking in jobs, venture capital, highly educated workers, and the various benefits (and occasional challenges) that come with those attributes. The rest of America’s cities, not to mention its small towns and rural communities, were increasingly being left behind.

The contest to choose a new Amazon headquarters was symbolic of this frenzy, with hundreds of locales begging the retail giant to pick them, complete with promises of tax breaks and other incentives. Then they watched Jeff Bezos choose the D.C. area and New York City—winners taking all, yet again. (New York later backed out, under pressure from progressives, and Nashville got something of a consolation prize.)

Bezos et al. faced plenty of criticism for giving hope to the underdog cities and making them cough up data that Amazon could exploit for other purposes. Yet it was hard to fault their final decision. As the Brookings Institution’s Alan Berube wrote, it was all about “talent, talent, talent.”

There’s little doubt that the New Yorks, Bostons, D.C.’s, and Silicon Valleys are very effective at attracting talented and highly educated workers. In a virtuous cycle, these individuals migrate to where the highly paid jobs are, where lots of other smart young people live, and where all manner of amenities make their nonworking life more fun. But workers are also drawn by the promise that their own children, whether extant or prospective, will enjoy high-quality public schools in their new home towns.

But is that actually true? Do the “superstar cities” boast better public schools than those in the Rust Belt or Sun Belt? Business leaders often say the quality of local schools is a key factor when choosing new locations for corporate headquarters or facilities. But are they looking at the right data when judging school quality?

Label us skeptics

Longtime followers of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute won’t be surprised to learn that we are skeptical of how school success tends to be measured. It’s not the fault of the business leaders—or even the economic development folks who strive to woo them. It’s simply a fact of data availability and access. Until recently, few sources allowed nationwide comparisons of schools below the state level. And those sources that did exist, such as average SAT scores or graduation rates, are terrible at helping us understand the quality of the schools. That’s because such “status measures”—snapshots of performance—are so closely related to the demographics of individual schools and districts. It’s why, for so long, communities that have touted their “great public schools” were actually just bragging about schools populated by the children of highly educated parents.

That’s a lousy definition of school quality because it doesn’t consider whether schools are actually effective at helping students learn. It allows the schools in upper-middle-class suburbs to rest on their laurels, while hiding the amazing work done at many high-poverty schools, whose students start out way behind but may make remarkable progress year to year—even if they never quite catch up to the more advantaged kids. Not every high-poverty school pulls that off, not by a long shot, but more succeed at it than you might think, certainly more than city-comparers have been able to see.

So in Fordham's new report, America’s Best and Worst Metro Areas for School Quality, we wondered: If we could measure school effectiveness the right way, by looking at student progress over time, would a different picture of school quality emerge? And in particular, could we start to determine at the metro-area level which American regions really have the best—i.e., the most effective—schools? Might such an analysis assist business leaders in giving more metros another look when making locational decisions—especially in the post-pandemic world, now that so many workers are rethinking their commitments to “superstar cities” with their sky-high housing prices, soul-grinding traffic, and distance from family?

As for the challenge of usable data, that one has been solved, thanks to the impressive Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA). Leveraging state summative assessments and adjusting them for states’ performance on NAEP, the analysts at SEDA have enabled previously impossible comparisons of schools, districts, and cities across the land.

Equipped with these excellent data, we set out to build valid comparisons at the metro-area level for school quality across the United States, complete with an interactive website. We are grateful that our friends and colleagues at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation agreed to join us in this pursuit. The Chamber’s affiliates are key players in economic development decisions, active in recruiting employers to their regions. They are integrally involved in local education issues, too, as major funders and consumers of the education system. Readers may also remember that the Chamber has a long history of educational rankings, going back to its excellent Leaders and Laggards series. We greatly appreciate the Chamber’s support and involvement.

We’re also deeply grateful to external reviewers Kristin Blagg, senior research associate at the Urban Institute, and Stephen Holt, assistant professor of economics at SUNY Albany, for offering advice on the rankings methodology and reviewing the interactive website; to Fordham’s associate director of research Adam Tyner for serving as lead analyst, project manager, and number-cruncher; and to Juan Thomassie for designing the interactive website.

Introducing the SLAM rankings

Because we thrive on catchy acronyms, we’re calling these rankings the Student Learning Accelerating Metros, or SLAM. The measures that go into these rankings are those most clearly connected to school effectiveness and that are available nationally at the school district level—namely:

- Academic growth (worth 60 percent of the score in our preferred ranking system).

- Academic growth for traditionally disadvantaged students (worth 20 percent).

- Improvement in achievement in recent years (worth 10 percent).

- High school graduation rates (worth 10 percent).

All these measures are adjusted for demographic differences in districts’ pupil populations.

What’s different about the SLAM rankings compared with other measures of school quality is that they correlate far less with family wealth and student background than do simple academic achievement ratings. They are heavily weighted toward student progress because schools have more control over how much their students grow during the K–12 years than they do over, say, the percentage of residents with a doctorate degree (which other rankings use).

So enough with the preliminaries. Let’s look at the results.

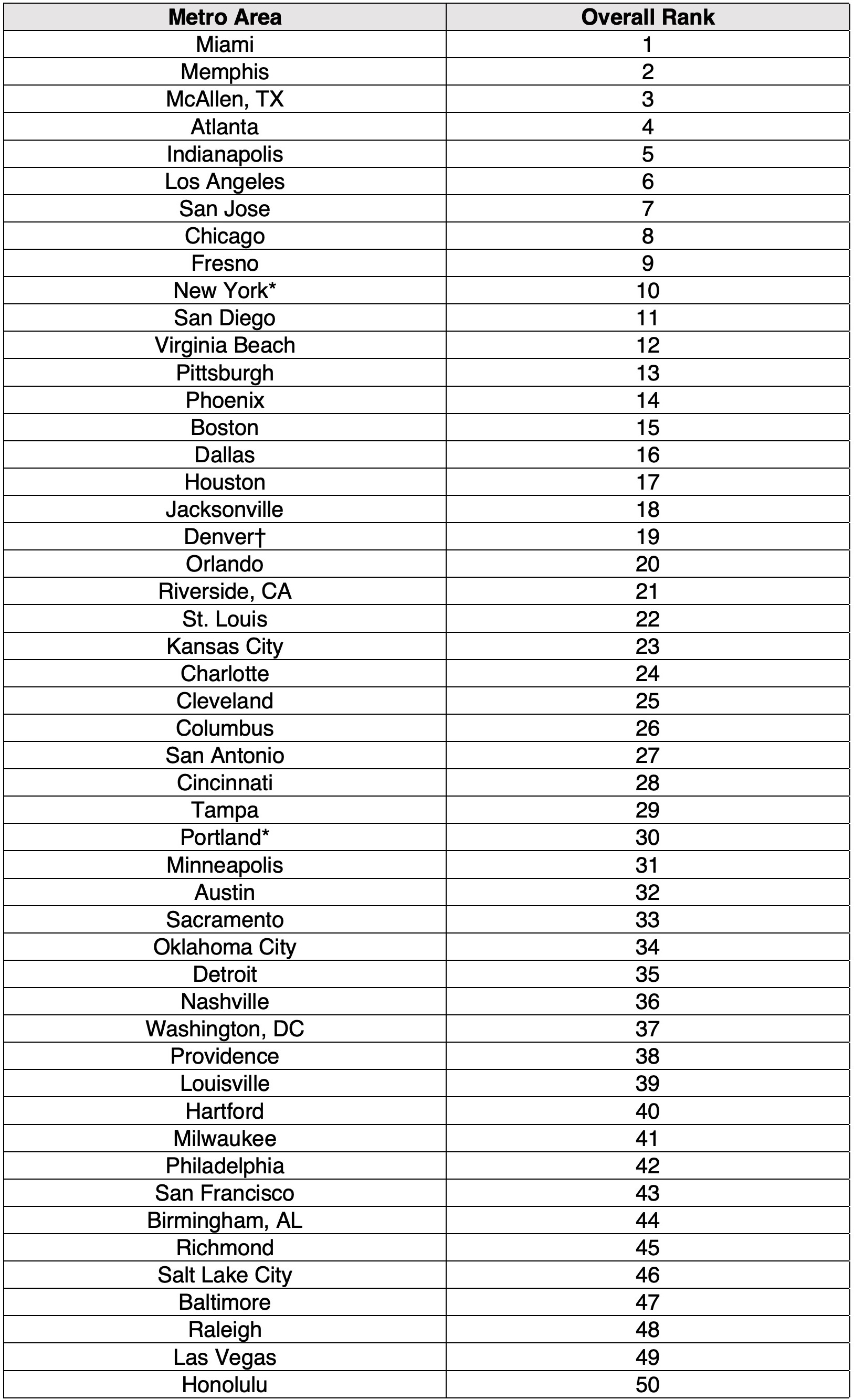

Table 1. America’s fifty largest metro areas ranked by school quality

Note: Each metro represents a core-based statistical area that includes nearby suburbs, towns, and other cities. Metro area names are abbreviated for legibility; full names appear in the report’s Appendix. All outcomes are adjusted for district-level demographics.

*Metro is missing data for its largest district for all recent observations, meaning New York City Public Schools and Portland Public Schools.

†Key data points are missing in the early years of the SEDA data. Because missing early data makes it impossible to calculate metro progress, the value for that variable is imputed to align with the metro’s performance on the other components of the SLAM ranking.

What should be clear is that some superstar cities do better than others. The Miami metro area—South Florida really, including Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties—comes out as number one. The “capital of Latin America” has been on a tear of late, increasingly attracting venture capital and corporate headquarters, especially in the finance industry. New arrivals will find excellent schools for their kids.

The Boston metro area does quite well, too. To be sure, it’s affluent and well educated, which is not surprising, given the presence of so many world-class universities, medical centers, and tech companies. But schools there aren’t standing still. Students are making significant progress over time, as well, along with students in the Los Angeles, San Jose, and Chicago metro areas.

Yet that’s not so in some superstar cities. The San Francisco metro area looks pretty bad, once we measure school effectiveness the correct way. The Washington, D.C., metro area is not much better. Or look at Raleigh, in the Research Triangle, which is way down on the list.

Be careful, too, not to confuse metro areas with their central cities. For example, Washington, D.C., itself shines on our ranking, thanks to its rapidly improving public school system and its highly effective charter school sector. The Northern Virginia suburbs of Fairfax and Loudoun County, however, are dragging the metro down. They are rich and highly educated, but their pupils don’t appear to be making much progress from year to year. Indeed, Amazon may have erred in placing its new headquarters in Northern Virginia instead of, say, Maryland’s Prince George’s County, which is less affluent and much more diverse but boasts schools that are helping kids make more progress, especially once we control for demographics.

Meanwhile, some other large metro areas deserve a fresh look, given the quality of their public schools, including Atlanta, Indianapolis, and Fresno. The rankings for Memphis, Tennessee, and McAllen, Texas stand out in particular, with remarkably effective schools despite their Deep South and Border Town poverty—likewise, the mid-sized metros of Jackson, Mississippi, and Brownsville, Texas. Other mid-sized cities deserve attention, too, including Sarasota, El Paso, Boise, and Grand Rapids. (See the full results for mid-sized metros in Table A3 in the report’s Appendix.)

—

Great public schools are essential to the health of any community. They’re a powerful driver of economic development. But we need to make sure we’re defining “great schools” correctly. Now, thanks to the new data provided by SEDA and the tools on Fordham’s new website, we can finally identify metro areas that have a right to brag about the quality of their school systems and charter schools—as well as places that would be well advised to stop patting themselves on the back and get a move on.