- Fordham’s indispensable data publication Ohio By the Numbers is quoted and linked in this story about kids opting for a path other than college—think masonry or real estate—after graduating from high school. (Fox 8 News, Cleveland, 9/19/22)

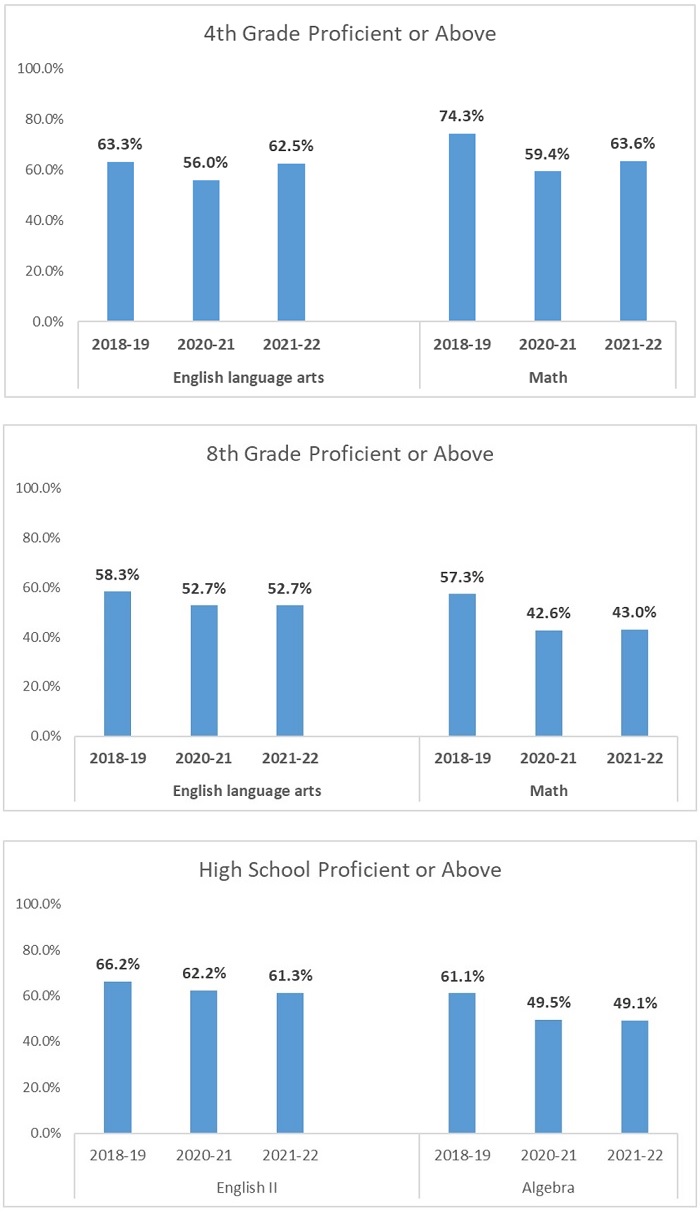

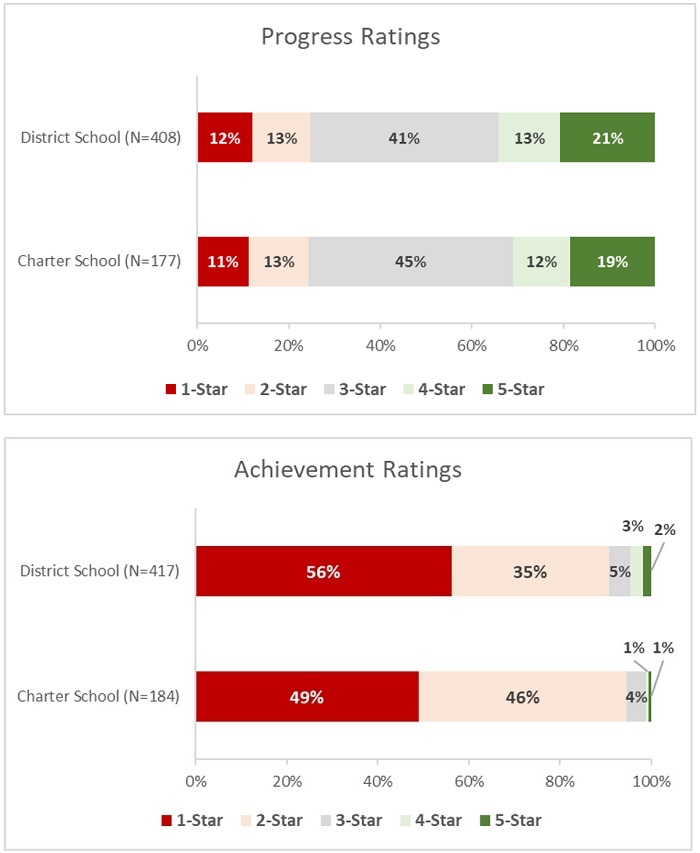

- While I might not normally love the previous clip due to its strong “college bad” vibe, it does feel like the two high schoolers interviewed were equipped with the skills to go either way. Which, I personally think, is the point of school. (And it’s not just me, either. See Item 5 below.) Those students simply chose the non-college path even though they could apparently have done either. But those options are not fully open for all of Ohio’s students, as I know you know. Here is another big-picture report card piece (which includes reference and links to Vladimir Kogan’s analysis as posted on the Ohio Gadfly blog) which seems pretty clear on whose students are getting the education they need to be able to make those post-graduation choices and whose students are not. (Dayton Daily News, 9/20/22)

- Parma City Schools’ superintendent confesses that he is “mystified” by his district’s report card. He tries to explain his befuddlement here, but it doesn’t sound entirely accurate to me. And I’ll bet his families know just what all those ratings mean. (Cleveland.com, 9/21/22) Personally, I appreciate when school officials simply own up to bad report cards and don’t waste time with the usual bafflement and “snapshot” nonsense. Kudos to Dayton City Schools’ supe for doing just that here, although there is still some deflection as to the cause. Additionally, our new report card star rating system has allowed for a brand new nonsense response that even I didn’t expect: “It's still better than zero stars.” Hilarious. (Spectrum News 1, 9/19/22)

- Anyone want to move to Steubenville? The principal of the high school there is touting a “near perfect” report card this year AND is promising to do even better next year. (WTRF-TV, Wheeling, 9/19/22) You can also, it seems, drink beer in the Steubenville public library upon occasion. See ya! (WDTN-TV, Dayton, 9/19/22)

- We come back to where we began with this clip. Toledo City Schools’ superintendent said this week that he believes simply getting a diploma is “settling” and calls that mindset “drinking the old TPS Kool-Aid” (super yucky phrasing, IMO, for a number of reasons). At a luncheon event for community stakeholders, Dr. Romules Durant explained that college AND career readiness should be the goal for all of his students and he touted existing and forthcoming career academies as the solution to get to that desired outcome. While I concur with the sentiment, I have very little confidence in this district’s approach to supposedly get there (not that anyone asked me, of course). Please do note the supe’s use of concrete outcome data for Toledo Early College Academy (a tiny bright spot in the district) versus the vaguer language used and lack of data provided related to apprenticeships for students at other high schools. The district’s poor report card showing is also noted briefly here—a fly in the “new Kool-Aid”, perhaps?—but Dr. Durant noted that the new version of the state’s “Prepared for Success” measure was not rolled out this year. Thus, his effort to fill the information gap for folks. How very generous. (Toledo Blade, 9/20/22)

- This story about future funding for tutoring in Ohio feels a little like looking ahead to when the ESSER money runs out to me. You? (Gongwer Ohio, 9/19/22) And finally, speaking of the state Board of Ed: How can we miss her if she doesn’t go away? (Toledo Blade, 9/19/22)

Did you know you can have every edition of Gadfly Bites sent directly to your Inbox? Subscribe by clicking here.