AEI’s foremost and very distinguished demographer, my long-ago colleague Nick Eberstadt, joined by several colleagues, has released a devastating analysis/critique of the much-cited OECD assertion that China’s K–12 education performance—based on PISA scores—is better than that of any other country with the possible exception of Singapore.

Although OECD reports, if you read closely, generally make clear that PISA has been administered to students in just a few regions of China[1], not the whole country, that doesn’t stop them from depicting the results as “China’s” nor from statements like this, taken from an exceptionally bullish 2020 report on Chinese education that OECD prepared jointly with Chinese authorities:

In all four cycles of PISA, Chinese students from these jurisdictions have outperformed the majority of students from other education systems. Even though the participating Chinese jurisdictions do not represent China as a whole, they are still considerably larger than many OECD countries: Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang together are home to over 183 million people, which is more than the combined population of France and Germany.

Note the disingenuousness of that formulation, as if the size of the selected subunits within China that were sampled and tested yielded data as valid as from other nations that happen to be smaller but where the entire population was sampled and tested.

As for how many Chinese fifteen-year-olds actually got tested and where they came from, the AEI paper drily says this:

[T]he PISA sample for China that year involved just 361 schools and twelve thousand students—about thirty-three students per school selected. We do not know the process by which those schools were selected, much less the identities of the schools themselves, or the protocols observed in conducting (and preparing for) the tests. Suffice it to say there would appear to be plenty of scope in this mysterious process for non-random results.

Here’s a bit more boasting from the OECD report itself:

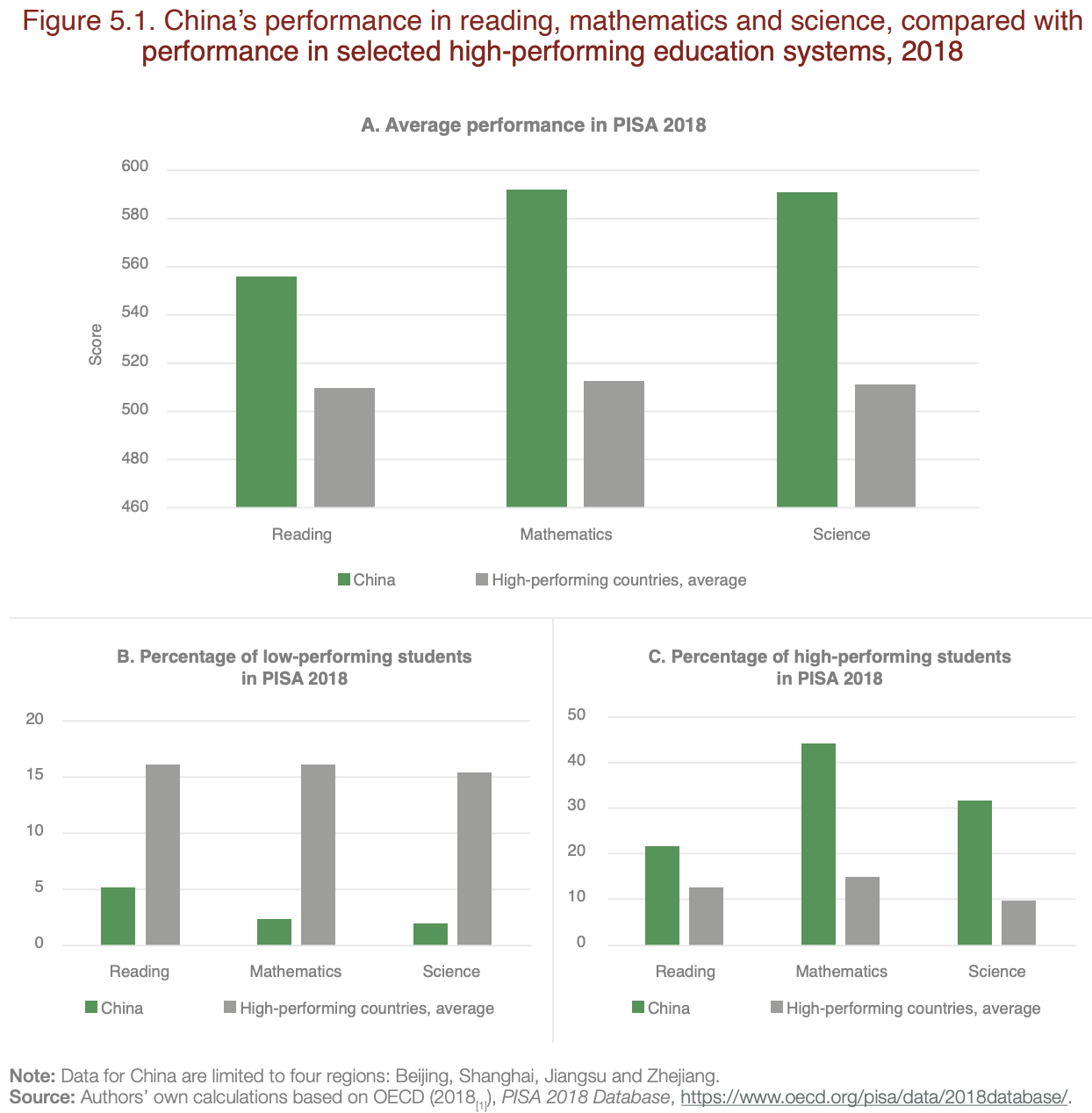

Students in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang (B-S-J-Z) outperformed their peers in other high-performing countries in all three PISA domains (mathematics, science and reading) by a large margin.... The excellence of student cognitive outcomes in B-S-J-Z (China) can be attributed to teacher and school characteristics to a large degree.

Which leads to displays such as this—from the same report—which imply that it’s the entire country unless you look at the small-font note at the bottom:

When these results get picked up by others, such as the World Population Review, the fine print vanishes and—voila—we seem to be looking at results for China as a whole.

Eberstadt and colleagues undertook a heroic reanalysis that didn’t just take PISA results from China at face value and assume that they’re representative of China. In a project initially carried out for the Defense Department, they engaged in a series of adjustments based on other information about educational performance of students in different parts of China, about student aptitudes (insofar as those can be gleaned from sparse data), and from “qualitative” information about schools, schooling, and demographics (including family structure) in various parts of China, and much more.

Here’s the blunt conclusion of a very sophisticated paper:

We use both quantitative and qualitative evidence to survey the field and emphatically reject the PISA-based assessment that places China first in the world. Instead, we come away with the working hypothesis that the knowledge capital of China’s K–12 population is on par with that of Turkey.

OK, it’s not a conclusion. It’s a “working hypothesis,” and in their almost-sixty pages the authors pay considerable attention to alternative explanations, contrary semi-examples (e.g., the educational performance of Vietnam), and ways in which different assumptions and interpretations—including Eric Hanushek’s careful analyses—yield different results that could be right. But they give what are, to me, reasonably persuasive justifications for their own “hypothesis.”

That said, China, simply because of its mammoth scale, does produce very large numbers both of children with basic skills and of high-fliers. The percentages may not be impressive, but the absolute numbers are large and (if the sampling can be trusted within the regions where it’s done) the percentages are sometimes impressive, too. Among those tested in math in the four Chinese regions in 2018, for instance, some 44 percent scored at PISA’s highest levels (5 and 6), compared with, say, 8 percent in the U.S. and 17 percent in Switzerland. Even if the Chinese data come from a narrow swath of that country’s population, and even if the data are suspect, we can glimpse America’s major competitor in the modern world producing large numbers of individuals with high levels of skill.

Why is this sort of analysis so frustrating as well as worrisome? As the AEI paper explains, and as pretty much every serious independent analyst of Chinese education has noted, the closed, secretive, and thoroughly censored nature of the country itself means that data are scarce, incomplete, and often untrustworthy. So scholars work with what they can get, what they deem reliable or plausible, what they can infer, and what they can bring to bear from other sources.

That’s what Eberstadt and company have done in a wide-ranging examination (that, among other things, sheds much worrisome light on India, a far more open society that has an immense number of children lacking basic skills, even as it has an immense number of college graduates lacking decent jobs). It’s worth attention, in part just to understand the basis for mistrusting what emerges from OECD when the topic is China.

SOURCE: Nicholas Eberstadt, Patrick Norrick, Radek Sabatka, and Peter Van Ness, “Knowledge and Skills in China’s K-12 Population: An Inquiry into “Knowledge Capital” in the PRC,” American Enterprise Institute, Foreign & Defense Policy Working Paper 2024-07, November 2024.

[1] Even within the four regions—all relatively prosperous, relatively well educated, major metropolitan areas in eastern China—not all fifteen-year-olds were in the samples tested by PISA. Participants had to be legitimate residents of those regions and to attend schools chosen to take part in PISA. See this important analysis by Tom Loveless.