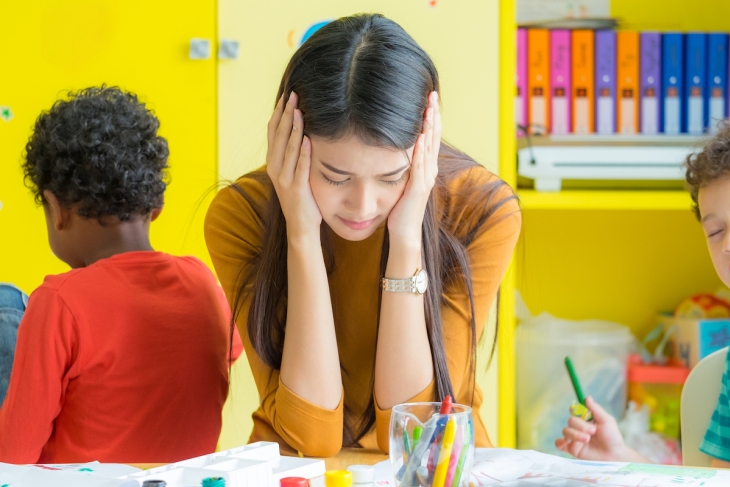

Long after Covid-inspired shutdowns, schools remain chaotic according to recent surveys and umpteen stories of hallway brawls, bus fights, and general mayhem. Teachers have told me it’s a crisis, that we’re accepting as normal in schools behavior that would warrant public outcry or arrest outside their walls. It’s no wonder analyses in recent years have found that stress and behavior topped pay as the primary reasons that teachers were considering leaving, and that they prefer stricter discipline policies.

With disorderly school environments that are at times actively hostile towards the wellbeing of both students and staff, I have a simple question: Where are the unions?

The answer: Nowhere to be seen.

For reasons that I struggle to comprehend, the national teachers unions have fully embraced the weakest approaches to school discipline, the kind that entail few or no consequences for misbehavior. AFT President Randi Weingarten has written against consequences, going so far as to praise the Los Angeles Unified School District for banning suspensions of students who defy their teachers. Of course, another way to describe a prohibition on punishment for defiance is to say that LAUSD has told children that they do not actually need to listen to or respect the adults in the building. Meanwhile, the NEA has published extensive guides and resource lists advising schools to replace punitive discipline with restorative practices.

The NEA also held its annual conference last week, where president Becky Pringle gave a speech that whined about Donald Trump, demanded equitable funding, genuflected before various progressive causes, complained about parents who take umbrage over sexually explicit books in public school libraries, and praised the Portland teacher strike, which included property damage, vandalism, and the publication on the internet of the addresses and contact information of various board members as a pressure campaign for higher wages.

No mention was made of student behavior or learning loss or much of anything else that goes on in classrooms really. Ironically, she spoke about the “joy of teaching” and “educator respect” while glossing over the very issue that most saps the joy from teaching. And if the NEA does end up discussing discipline policies, as Pringle has suggested it might, it will almost certainly do so counterproductively. They have consistently denigrated discipline in the past.

One of the foremost reasons for even having unions in the first place is for them to defend the interests of their members. Given that surveys—even those that unions themselves carry out—consistently find that student behavior is a primary reason that educators list as they consider leaving the profession, the unions ought to be a leading voice of sanity on this issue. Unfortunately, I doubt any discussion of our behavioral debacle is coming. So far as I can tell, two threads have resulted in this abdication of duty.

First, there’s a reaction against the popularity of zero-tolerance policies in the 1990s and early 2000s. Weingarten herself confesses her former support of these (supposedly) anachronistic policies. They’re the bugaboo that justifies an overcorrection. I’ll concede that the no-excuses trend went too far—handing out demerits for glancing at the clock—but the reaction has advanced to an opposite and equally incorrect extreme.

Second, a concern for equity and racial injustice has led administrators, policymakers, and activists to embrace the excesses of the DEI-social-justice bandwagon and thereby sluff off any remaining commitment to sanity. The NEA has published numerous guides and resource pages that make copious mention of the so-called school-to-prison pipeline—a laudable concern, but acknowledging disparities is not itself a justification for any policy.

Indeed, solutions popular with unions may only worsen the problem. When schools abolish suspensions for defiance or move from punitive to restorative practices, they create the kinds of chaotic, ungovernable schools that create lasting disparities between them and students educated in more orderly classrooms. Numerous studies confirm that misbehaving students are detrimental to the learning of their peers, and so by refusing to hold students accountable for their actions, restorative justice advocates construct a whole new school-to-prison pipeline. What good does it do Johnny if we keep him from suspensions or expulsions, but his school is full of fights, clamor, and disorder?

Regardless of the reason, I’m waiting for unions to step up and defend teachers. Leading unions have bucked progressive excesses for the good of teachers and children before. For example, in 1967, the UFT went on strike to win teachers more power to manage unruly students in their classroom. More recently, the AFT published a controversial smackdown of the Howard Zinn–ification of American social studies. These unions went on strike over sensible policies and have taken stances to check the progressives in their ranks. They should do so again. If anyone has the proper incentives to pick this fight and the resources at their disposal to pressure real improvements, it’s them. If they don’t, they’ll continue to cede this issue to their opponents. Already, Republicans have overtaken Democrats as the trusted party on education according to polls.

And indeed, there are efforts to support teachers, but it’s from the right—the side that’s usually associated with antagonism to educators. Most recently, Louisiana State Superintendent Cade Brumley released his “Let Teachers Teach” set of policy recommendations with an entire section dedicated to student discipline. These include removing discipline rates from school accountability systems so that administrators can maintain order without taking a hit in the state accountability system, empowering principals and school leaders to remove disruptive students from the classroom, and no longer asking teachers to play-act mental health professionals. Other conservative-led localities and states such as Oklahoma, Florida, and Houston have done likewise.

Albert Shanker infamously (if apocryphally) once quipped that, “When schoolchildren start paying union dues, that’s when I’ll start representing the interests of school children.” Now there’s a convincing case to be made that they don’t even represent teachers anymore. If their membership continues to plummet, they’ll have only themselves to blame.