A perennial complaint about holding students accountable through grades and test scores is that these mechanisms are biased against already disadvantaged students. This narrative may ultimately harm the students it is meant to defend, since research has shown that students can up their game when challenged and students learn more when taught by teachers with higher academic standards.

Since even advocates for abolishing A-to-F grading are typically realistic that some form of grading will continue for the foreseeable future, it is worth considering how we can expel racial bias in the grading system. That’s where a new study by David Quinn, a researcher at the University of Southern California, adds important new insight. Professor Quinn uses experimental data to examine how different grading practices may limit or exacerbate teacher bias.

But first, are teacher grading practices actually biased?

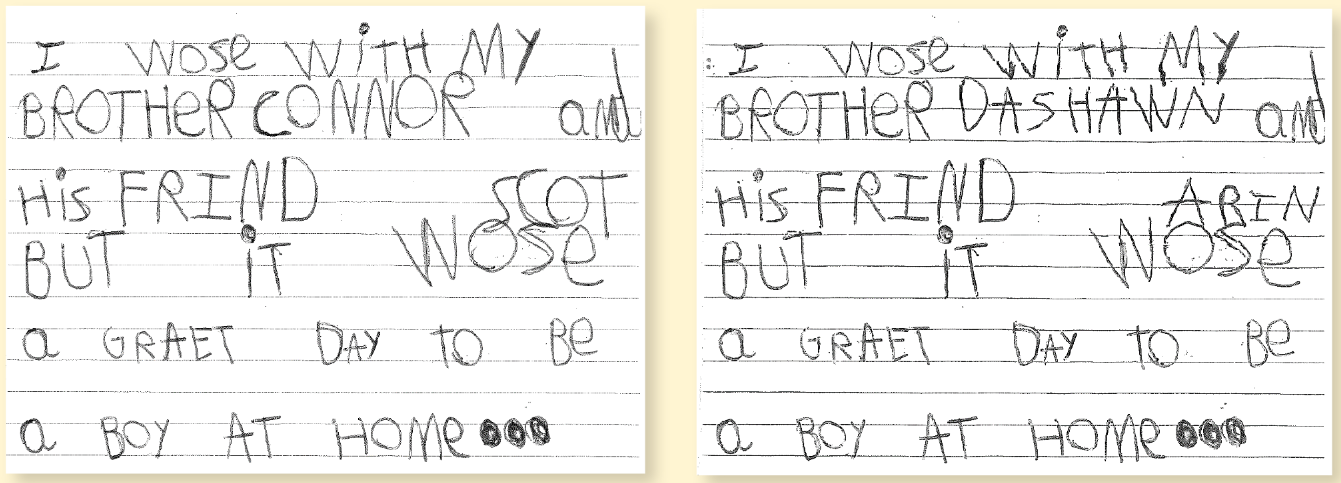

The methodology of this paper enables an answer to this question by isolating teacher racial bias in a clever way. Teachers graded sample assignments that were purportedly completed by real second grade students, but, as with previous studies on implicit bias, the artifacts that were rated by the teachers were carefully constructed by the researchers to be identical in every way except a reference to a name that subtly signals the student’s race. In a similar study of racial bias in callbacks for job interviews, the researchers sent out identical resumes, except for random alternation between “White” names like “Brendan” and “Black” names such as “Jamal.” In the present study, the fictional second graders wrote about their weekend, referencing their brother, whose name was either “Connor” or “Dashawn,” with the race-signaling names randomly assigned to different teachers by the researchers (see Figure 1).

Unfortunately, the study finds strong evidence of grading bias against Black students. White teachers who graded the work of “Deshawn’s” brother were considerably less likely to rate it at grade level than those who graded the work of “Connor’s” brother, despite the fact that the two assignments were identical. Women teachers also exhibited this bias, while teachers of color and male teachers did not exhibit bias towards the fictional Black student’s assignment. Disturbingly, those working in the most diverse schools were the teachers whose answers had the greatest grading disparity.

Figure 1: The writing samples are identical except for the race-signaling names

Source: David M. Quinn, “How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading,” Education Next (November 2020).

Thankfully, the study doesn’t end there. The teachers were also asked to grade assignments according to a detailed rubric. When grading according to the rubric, teachers exhibited no racial bias, with virtually identical ratings for the two assignments. This finding held among teachers in general, as well as among White and female teachers and those working in relatively diverse schools.

The study’s main strength—the anonymous grading of papers by fictional students, which enables the researcher to isolate the effects of race—is also a weakness, since it is unclear if teachers exhibit the same levels of implicit bias against students in their classrooms, whom they presumably know well. And because the study focuses on grades at the elementary level, where grading is lower-stakes (no one puts their elementary school grades on their college application), it is less clear what impacts these biases have. The author is aware of and admits these drawbacks, but they are worth restating here.

Still, the suggestion to use strict rubrics when grading is welcome, since clear grading criteria are fairer to students and help ensure uniformity of standards. Of course, it is not feasible to use such rubrics in every subject or for every assignment, since, for example, a creative writing assignment may require the student to color well outside any rubric’s lines. But for many types of assignments, clear rubrics help. In higher grades, “blinding” student work by removing identifying information prior to grading can also help teachers to avoid not just potential racial or gender bias, but also bias against specific students about whom they have already formed opinions.

Removing bias from grading is doubly beneficial. Not only are grades more accurate and, thus, more legitimate signifiers of academic merit, but students who may be unfairly disadvantaged by some grading practices can be surer that they are on an equal playing field with their peers.

Reviewed: David M. Quinn, “How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading,” Education Next (November 2020); based on David M. Quinn, “Experimental evidence on teachers’ racial bias in student evaluation: The role of grading scales,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 42, no. 3 (2020): 375–92.