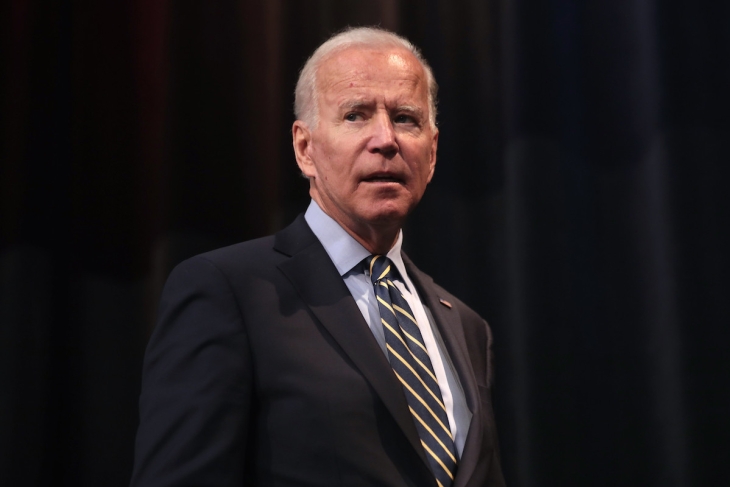

The Biden administration is proposing an unprecedented rewrite of the bipartisan federal Charter Schools Program (CSP): new regulations that are unprecedented not just for the CSP but for all federal K–12 programs. They would add pages of new requirements for applicants that are not in the statute and are unrelated to student outcomes. Instead, they focus on inputs. Rather than enforcing existing statutory safeguards that were negotiated by both parties and are intended to ensure that high-quality public charter schools can launch or grow without governmental micromanagement, the Education Department would act like a national charter school board, complete with one-size-fits-all rules for when a charter school should open (or not).

Such regulations would severely narrow what types of schools could even apply for federal funding for startup or expansion grants. They empower districts to disadvantage charter openings near them by refusing to cooperate on mandated “partnership” priorities. They also have the potential to ripple through state charter laws and policies in ways that make it harder for all charter schools to open or get renewed by their authorizers.

Wrong-headed standards for “community impact”

The impact that a charter school may have on its community is best evaluated as part of the authorizing process by people who know the context of that community. Yet the proposed regs would grant authority to nameless and unaccountable reviewers to award points depending how well they feel the new federal definition of community “impact” has been met. The criteria appear to be more about protecting the perceived interests of school districts than the educational interests of children.

For example, there is no consideration of whether there are enough seats in high quality schools to serve the most underserved students. Nor is the possibility even considered that a charter could boost the outcomes of district schools, as multiple studies have found to be the case. It treats district enrollment and demographics as the gold standard, when in fact many are vestiges of red-lining and other attempts to restrict access to higher quality schools. In many places, charter schools are how students whose educational needs are not being met by the district get access to a high-quality education.

Another troubling element in the proposed new rules is the expectation that a charter school’s mission is to serve “extra” students that exceed district capacity:

“Charter school must provide evidence that demonstrates that the number of charter schools proposed to be opened, replicated or expanded...does not exceed the number of public schools needed to accommodate the demand in the community.” (Community Impact Analysis requirement (e)) (emphasis added)

That language implies that charters should not open in communities with flat or declining enrollment—which, in the wake of the pandemic and a longstanding baby bust, is the reality in many communities.

This comes on top of existing federal law that already requires community engagement and consideration. When a school receives an approved charter, it means the applicants have gone through a rigorous approval process that examines the justification for their new (or renewed) school. Current requirements include community engagement. The new rules set forth a burdensome one-size-fits-all requirement that will scare many smaller and less well supported applicants from applying.

New roadblocks for culturally affirming schools and those that serve indigenous populations

The essence of charter schooling is enabling a wide range of public school models to open and empowering parents to choose what model works best for their children. The administration’s new rules would insist that a school must be “diverse,” regardless of its location or the preferences of its community. Current law encourages diverse charter schools, but it also encourages and allows for other models, such as dropout recovery schools. Nor does it dictate the process that must be followed to open a diverse school. The proposed new rules do precisely that. Perhaps in recognition that the proposed requirements could be read this way, they attempt to clarify in the explanatory text on page 14,200 that “an applicant that proposes to operate or manage a charter school in a racially or socioeconomically segregated or isolated community still would be eligible to apply for funding, even if the student body of the charter school would be racially or socio-economically segregated or isolated due to community.” But that language has no legal impact on how the grants will be scored by peer reviewers, and they could very well prevent the funding of those grants based on the proposed regulatory criteria.

—

In summary, these regulations would have a chilling effect on the number of CSP applicants, even as parental and student demand for slots in high-quality charter schools continues to rise across the country. From small single-site school operators to large CMOs, all will have difficulty responding to these new requirements. While the rules include some reasonable provisions regarding transparency around management contracts, their overall effect signals that the administration wants to rein in charter schools—and to force its own narrow “vision” of when and where they should be allowed to operate. It is doubly unfortunate that, today, when there is more agreement than ever on the need for different learning opportunities for students, the Education Department would put the brakes on charter school growth and make it harder to open culturally affirming public schools in order to serve some of the highest need communities in the country.