Now that the most acute phase of the Covid crisis is over, public conversation has turned to the millions of students who are still struggling academically and emotionally—and how our nation’s schools ought to respond. Decisions that education leaders make right now will determine whether this generation of students recovers or continues to lose ground. That’s why policies that lower expectations—such as rescinding “third-grade reading guarantees” or keeping pandemic-era no-grading policies in effect—are so troubling.

Are we really helping students by lowering the bar? What sorts of expectations should teachers set as they begin to dig out? And what can research and prior experience—particularly from the charter sector, where the need for high expectations has long been a rallying cry—teach us about how to approach this monumental challenge?

Conducted by American University’s Seth Gershenson, this study uses nationally representative survey data to explore how teacher expectations differ by sector, and how they affect achievement, attainment, and other outcomes.

To read the full report and its implications for educational leaders and policymakers, scroll down or download the PDF (which also includes the appendices).

Foreword

By Amber M. Northern and David Griffith

Among the most pernicious consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic was a general lowering of expectations for students. Many districts simply stopped tracking attendance during the shift to remote learning.[1] Others softened their grading policies[2]—or eliminated letter grades altogether.[3] Some teachers moved away from assigning “homework” on the grounds that students were already home and probably spending too much time on screens.[4]

Perhaps it’s unfair to second-guess those pandemic-induced changes (though not nearly as unfair as the generation-hobbling decision to shutter so many schools for so long, despite ample evidence that it was possible to reopen safely). But if we’re serious about getting our students back on track, we must be even more serious about getting our expectations for them back on track. Muttering the phrase “high expectations for all students” just doesn’t cut it.

1. In general, teachers in charter and private high schools are more likely to believe that their students will complete four-year college degrees.

2. In hindsight, teachers in charter and private schools were also more likely to overestimate students’ actual degree attainment.

3. In general, students in charter and private schools are more likely to believe that their teachers think “all students can be successful.”

4. Regardless of sector, teacher expectations have a positive effect on long-run outcomes such as college completion, teen childbearing, and receipt of public assistance.

1. All students need teachers who expect great things of them — and behave accordingly.

2. More families should have the option of enrolling their children in charter and private schools where high expectations are a core principle.

3. Above all, schools shouldn’t use students’ continuing challenges as justification for lowering expectations in the wake of the pandemic.

Introduction

Introduction

Although we don’t know as much as we’d like about what makes for an effective teacher, evidence is coalescing around the importance of high standards and high expectations, which seem to boost an array of student outcomes, including test scores, college completion, and everything in between.[21] We also know that parent and student expectations matter. For example, girls’ higher expectations for educational attainment are a primary reason the gender gap in school performance has reversed in recent decades.[22]

Yet, despite the fact that many charters are founded on the mantra of accountability, rigorous standards, and high expectations, surprisingly little is known about how expectations—including but not limited to those of teachers—operate in the charter school context. Much the same can be said about private schools, which often have a specific focus on college prep.

Understanding whether there are sectoral differences in the level and impact of teachers’ expectations for students could provide new insight into the mechanisms through which charter schools boost student achievement. Ultimately, it could improve how we recruit and develop educators for all sectors.

To look into these differences, we analyze nationally representative survey data from the 2002 Educational Longitudinal Study (ELS) and the 2009 High School Longitudinal Study (HSLS), which track the cohorts who were in the tenth grade in 2002 and 2009, respectively. Because they capture several postgraduation years, they tell us a great deal about students’ postsecondary schooling and early work histories.[23]

Background

Background

Students at every level frequently articulate their preference for, and the importance of, teachers who believe in them.[24] Similarly, parents and educators have long sensed that high expectations on the part of teachers are critical to children’s success. However, the modern debate over whether and how such expectations affect child development has its origins in the classic psychology experiment conducted by Rosenthal and Jacobson, in which teachers were told that some (randomly selected) students were unusually talented.[25] Famously, these students went on to display larger test-score gains, a result sometimes dubbed the Pygmalion Effect. Yet successive attempts to replicate this provocative finding yielded mixed results.[26] And of course, experimentally manipulated beliefs about students are not necessarily the same as “real” expectations. Consequently, some researchers have used quasi-experimental methods alongside high-quality survey and administrative data, with the goal of teasing out the impacts of teachers’ real-world expectations and biases.

Such analyses are challenging, as a host of other factors could influence both teachers’ expectations and children’s outcomes, and only in the past decade has credible evidence emerged on the importance of expectations.[27] For example, one recent study used administrative data from North Carolina to document the arguably causal effects on students’ academic achievement (measured by end-of-year standardized tests) of having a high-expectations teacher in grades 3–8.[28] Similarly, the study that laid the groundwork for the present study used a nationally representative survey of U.S. tenth graders in which two teachers of each student were asked how much education they expected the student to complete; the authors found that all teachers were overly optimistic, on average, and that optimistic teachers significantly increased the chances that their students would ultimately complete a college degree.[29]

Meanwhile, a culture of high expectations is a common feature of many successful charter schools,[30] especially those that have taken what has been called a “no-excuses” approach to high achievement (e.g., KIPP).[31] These lofty expectations generally start with the school leadership and teachers but are expected to trickle down to students and parents as well. However, because these schools are also known for qualities such as increased instructional time, consequential behavioral policies, and an explicit focus on boosting student achievement,[32] it’s hard to determine the extent to which these inputs and practices—as opposed to high expectations per se—are responsible for their success. Ditto for private schools, which typically have greater resources and a better-off student body, making it difficult to distinguish a culture of high (optimistic) expectations from accurate expectations based on the many advantages enjoyed by private school students, just as it’s hard to distinguish the impact of those expectations from other home and school inputs.

In short, despite the apparent connection between high teacher expectations and mission-driven charter and private schooling, much remains to be examined.

Data and Methods

Data and Methods

Data for this study come from two sources: the ELS and the HSLS.[33] In addition to being nationally representative, these surveys are longitudinal, meaning they track participants from their early years in high school through college and into the labor force. Specifically, the ELS conducted follow-ups four and ten years after the initial survey, when respondents were about twenty and twenty-six years of age, respectively. Moreover, both surveys contain rich information about individual students, teachers, and schools.

Importantly, every student in the ELS was assessed by at least two teachers, each of whom was asked, “How far in school do you expect this student to get?” In contrast, the closest thing to measuring teachers’ expectations in the HSLS is a question about students’ assessments of their teachers’ general expectations for students in the school. Specifically, ninth graders were asked to what extent they agreed with the statement, “Your math teacher thinks all students can be successful.” Finally, both datasets include straightforward measures of student and parent expectations for the student’s future educational attainment. To simplify the analysis, we generally collapse these responses into binary indicators for “expects at least a four-year college degree.” For the exact wording of each survey question, see Appendix A.

This study seeks answers to the following questions:

1. To what extent do teachers’ expectations for their students—and students’ perceptions thereof—differ by school sector?

2. How accurate are teachers’ expectations?

3. To what extent are any sectoral differences in expectations due to differences in student or school characteristics?

4. To what extent does the impact of teachers’ expectations on students’ long-term outcomes differ by school sector?

To answer the first two research questions, we compare average teacher expectations across sectors and compare expectations to actual student outcomes, respectively. To answer question three, we control for observable school and student characteristics. The school level characteristics we adjust for include school size (enrollment), locale, and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. The student-level characteristics we adjust for include race and sex, mother’s educational attainment, family income, language spoken at home, and standardized math score at the end of ninth grade.

To answer the final research question, we exploit the fact that two teachers assessed each student in the ELS. This allows us to control for one teacher’s expectations when gauging the impact of another’s, thus accounting for any unobservable student characteristics insofar as both teachers observe them. In a nutshell, we are comparing students with similar academic backgrounds, sociodemographic characteristics, and expected educational outcomes according to one teacher—who differ only in what a second teacher expects of them.

For more on the model, see Appendix B. For more on the causality premise, see Appendix C.[35] For more on data not presented, see Appendix D.

Findings

Findings

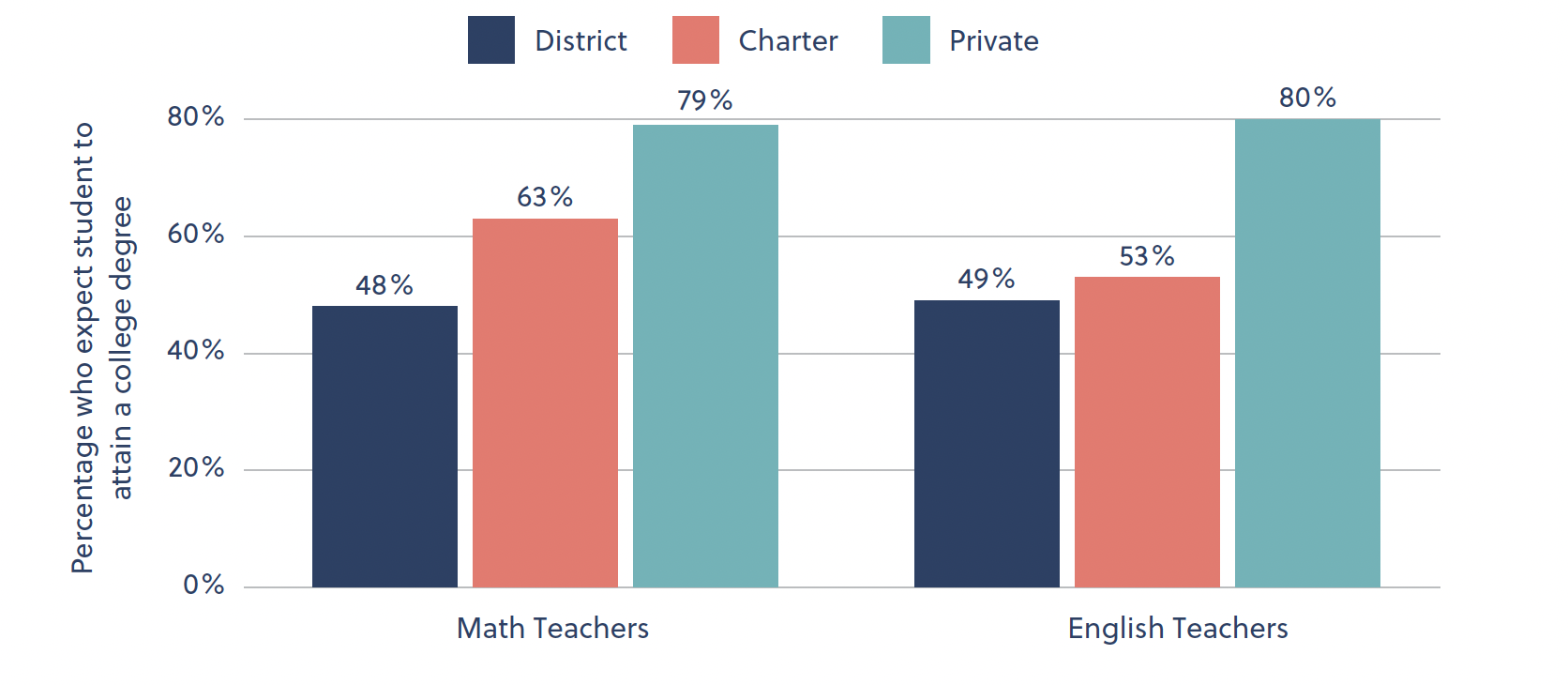

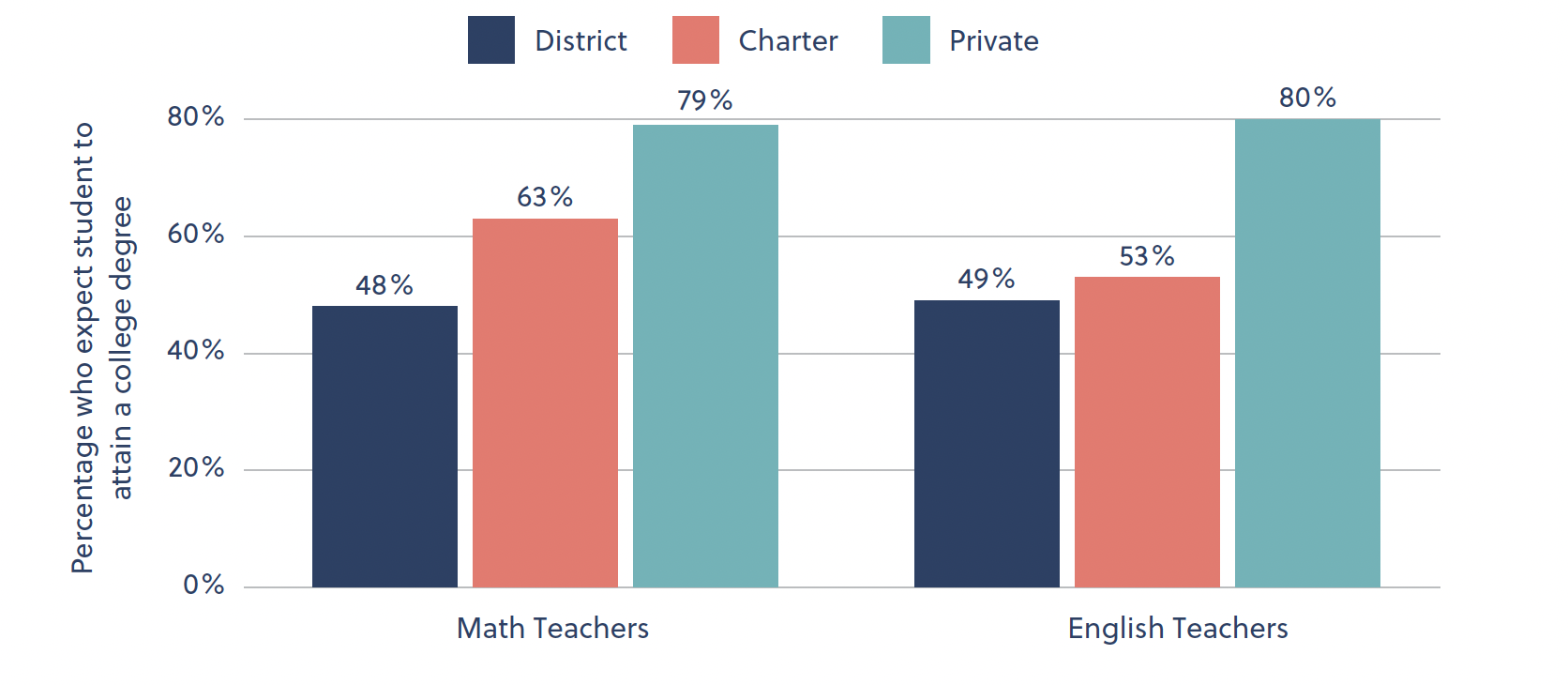

Finding 1: Teachers in charter and private high schools are more likely than their district counterparts to expect their students to complete four-year college degrees.

Collectively, teachers in traditional (district-operated) public high schools expected slightly fewer than half of their students to complete four-year college degrees (Figure 1). In contrast, private school teachers expected about 80 percent of their students to complete such degrees. In charter schools, math teachers were roughly halfway between these extremes, while English language arts (English) teachers held expectations that were closer to their district counterparts. Again, these are raw averages that do not adjust for student or school characteristics (which we’ll do next).

Figure 1. Teachers in charter and private high schools are more likely than their district counterparts to expect their students to complete four-year college degrees.

Note: This figure shows the percentage of ELS students whose math and English teachers expected them to earn a four-year college degree (or more).

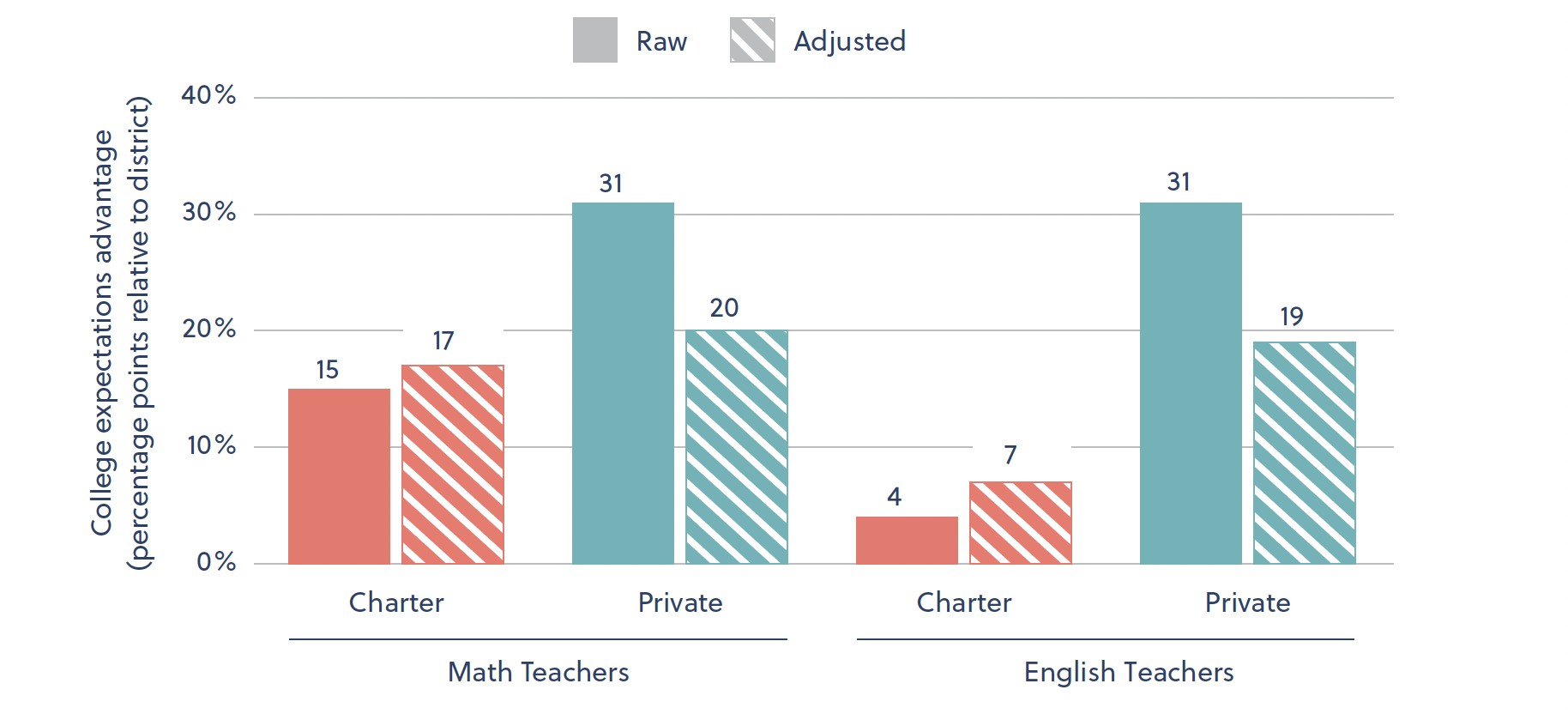

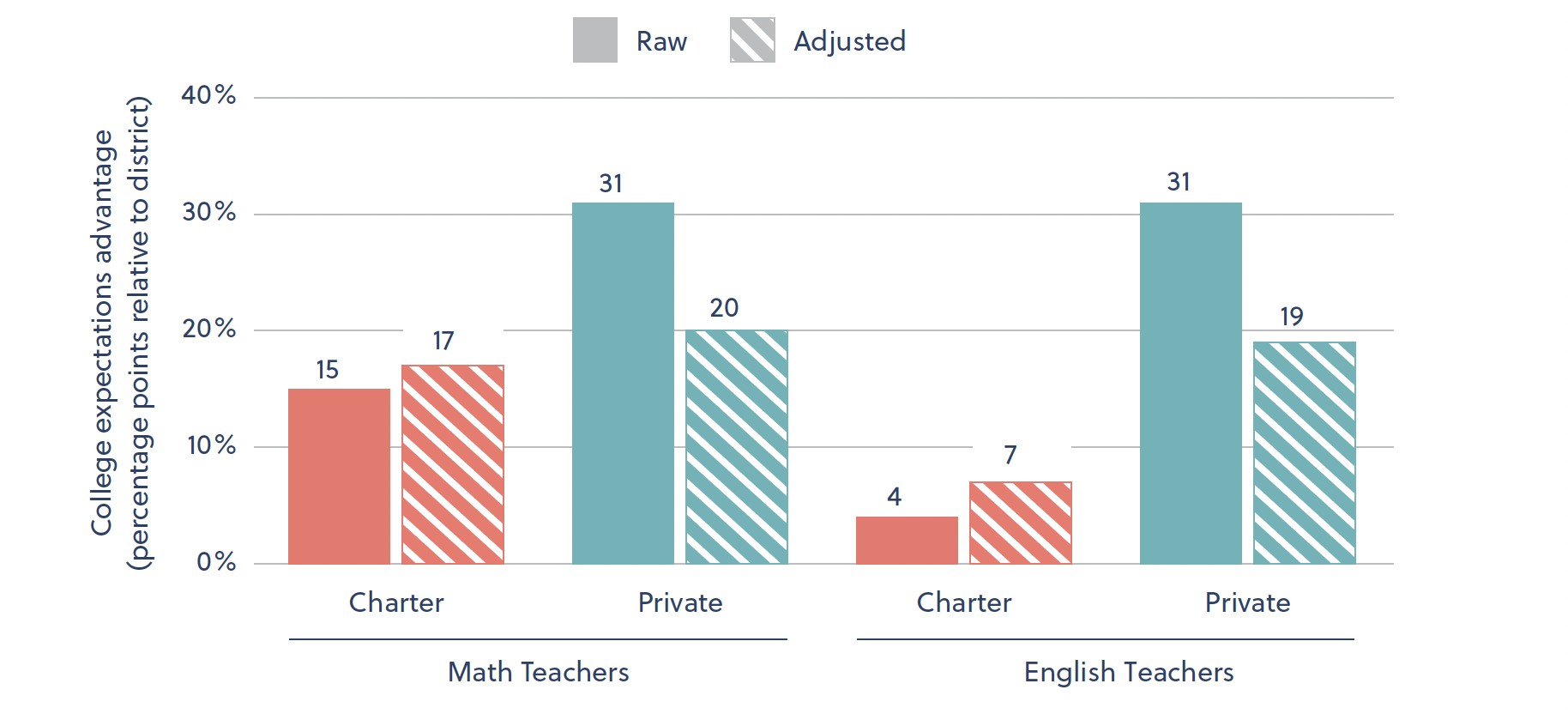

Note: This figure shows the percentage of ELS students whose math and English teachers expected them to earn a four-year college degree (or more).Importantly, the charter and private school advantages in teacher expectations are not due to observable differences in student or school characteristics (Figure 2). In fact, the gap between charter school and traditional public school teachers’ expectations increases after making those regression adjustments, suggesting that the charter advantage is (if anything) understated due to unobserved selection.[36] The private school advantage, on the other hand, shrinks by about one-third after making these adjustments, in large part due to the household-income disparity present in the raw comparisons, though it still remains large and statistically significant.

Figure 2. Even after adjusting for student and school characteristics, charter and private school teachers have higher expectations than teachers in traditional public schools.

Note: Bars represent the difference between charter or private school and traditional public school teachers’ expectations before (raw) and after adjusting for student and school characteristics. The underlying regression estimates for this exercise are reported in Appendix Table D2.

Note: Bars represent the difference between charter or private school and traditional public school teachers’ expectations before (raw) and after adjusting for student and school characteristics. The underlying regression estimates for this exercise are reported in Appendix Table D2.It’s interesting that, while the private school advantage is similar across subjects, the charter advantage is notably larger among math teachers. Mechanically this is because charter English teachers’ expectations are lower than charter math teachers’ expectations; in traditional public schools, math and English teachers’ expectations are quite similar (Figure 1). Why might this be? One possible explanation for this is that in charter schools that foster a general culture of high expectations, it may be easier for math teachers to buy into the idea that all students can succeed because most math learning takes place in schools and/or because math achievement is measured more objectively than is English achievement. Finding 2 provides some evidence of this.

Finding 2: Teachers in charter and private schools are more likely to overestimate students’ actual degree attainment.

Previous research suggests that on average, teachers are overly optimistic in the sense that they expect more students to complete a four-year college degree than actually do.[37] Given the sectoral gaps in high expectations identified in Finding 1, a natural follow-up question is whether those gaps mimic sectoral gaps in college-graduation rates. We examine this question by checking to see what percentage of teachers’ stated expectations (when students are in the tenth grade) turn out to be incorrect eight years later.

First, however, let’s look at accuracy rates. Overall, both math and English teachers in the ELS are correct about 71 percent of the time, meaning they accurately predict whether students will or will not complete a four-year degree. These accuracy rates are fairly similar across sectors, particularly in traditional public schools and private schools. However, charter school math teachers are something of an outlier, with a 62 percent accuracy rate. Of course, the way in which a teacher is wrong matters, as being wrong about a student who eventually completes college implies pessimism, which is potentially harmful, whereas being overly optimistic is mostly harmless.

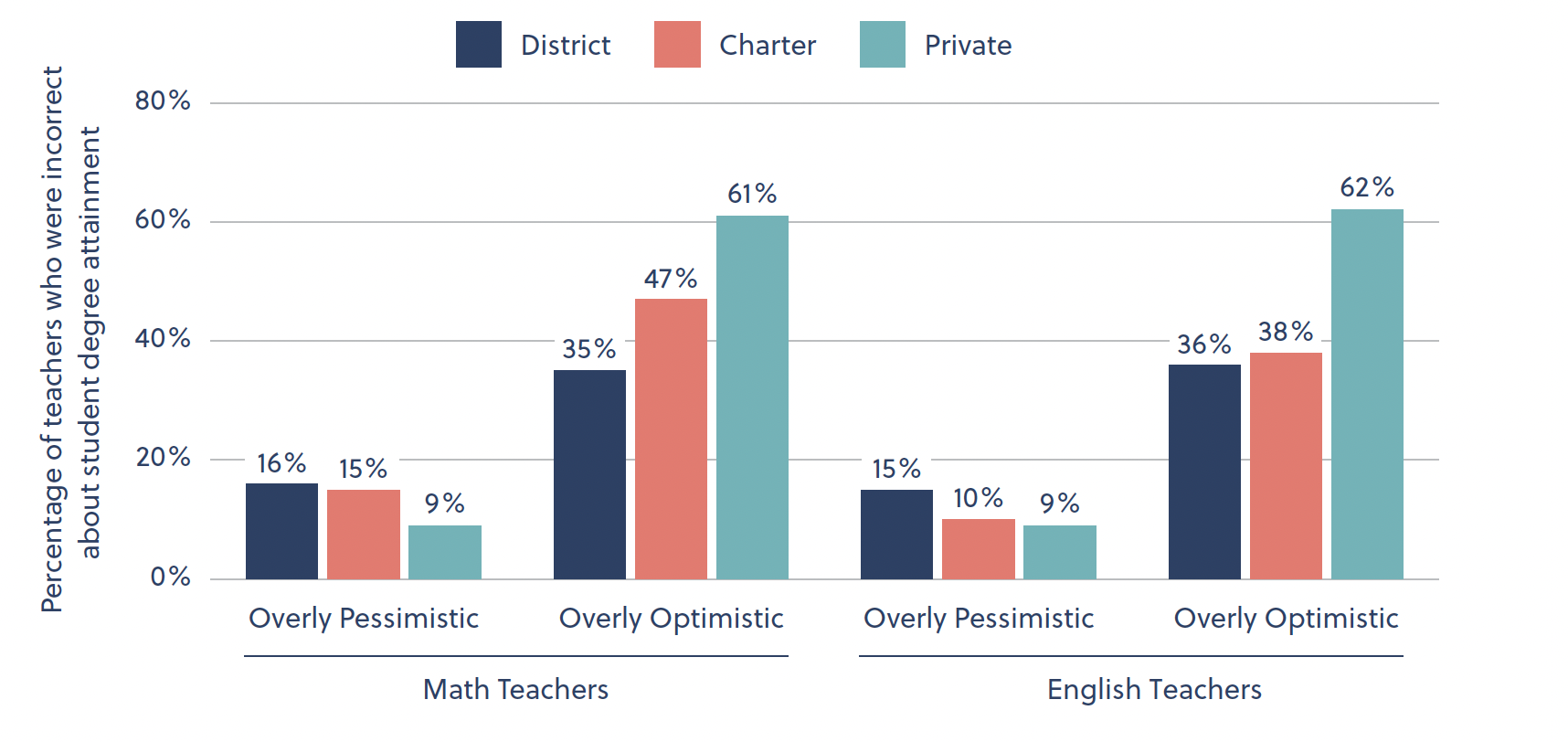

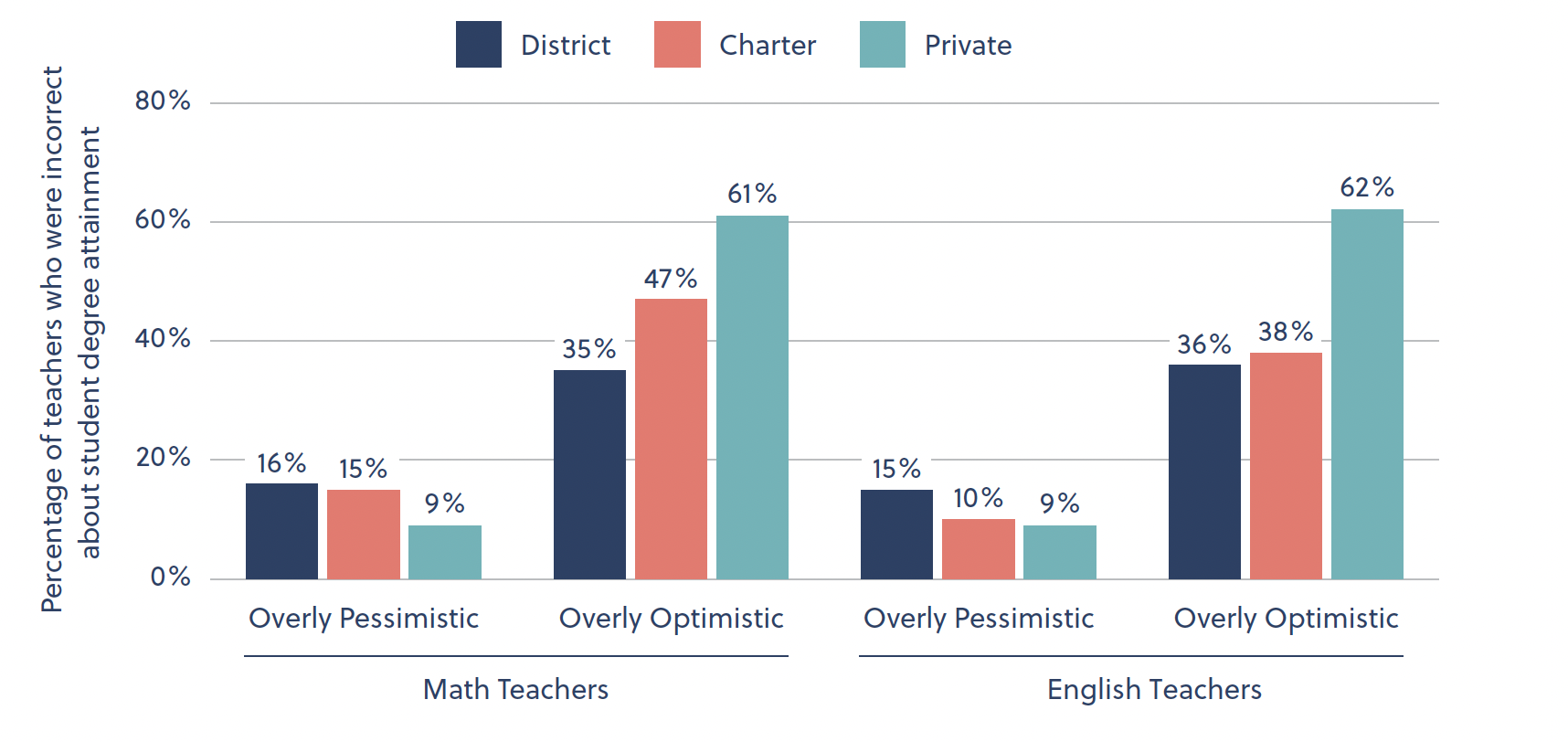

Decomposing the inaccuracy of teachers’ expectations separately by sector and by students’ eventual attainment reveals a few interesting patterns. Figure 3 shows that traditional public school teachers tended to be more pessimistic than their charter and private school peers. This led them to be both more accurate in identifying students who would fail to graduate college but also less accurate in identifying students who did go on to earn a college degree. Math and English teachers in traditional public schools were inaccurate for about 15 percent of eventual college graduates and for about 35 percent of those who did not graduate college. These figures are in stark contrast to private school teachers, who were more likely to err on the side of optimism and thus were inaccurate about the prospects of less than 10 percent of college graduates but more than 60 percent of students who didn’t graduate college. Private school teachers, one might say, had unrealistic expectations about how many of their students would eventually graduate college. That, of course, may be related to the “everyone from here goes to college” signal sent by many private schools.

Charter school teachers’ inaccuracy tends to be somewhere in between traditional public school and private school teachers. The most notable difference between charter school and traditional public school teachers’ inaccuracy rates is in math teachers’ predictions: charter school math teachers were twelve percentage points (33 percent) more likely than their traditional public school counterparts to inaccurately predict that their students would graduate from college. In other words, they were overly optimistic.

Figure 3. Traditional public school teachers tend to be more pessimistic than their charter and private school peers when it comes to students' actual degree attainment.

Note: This figure shows the percentage of teachers who were incorrect about the actual eventual attainment of college graduates (defined as overly pessimistic) and nongraduates (defined as overly optimistic) separately by subject and sector.

Note: This figure shows the percentage of teachers who were incorrect about the actual eventual attainment of college graduates (defined as overly pessimistic) and nongraduates (defined as overly optimistic) separately by subject and sector.

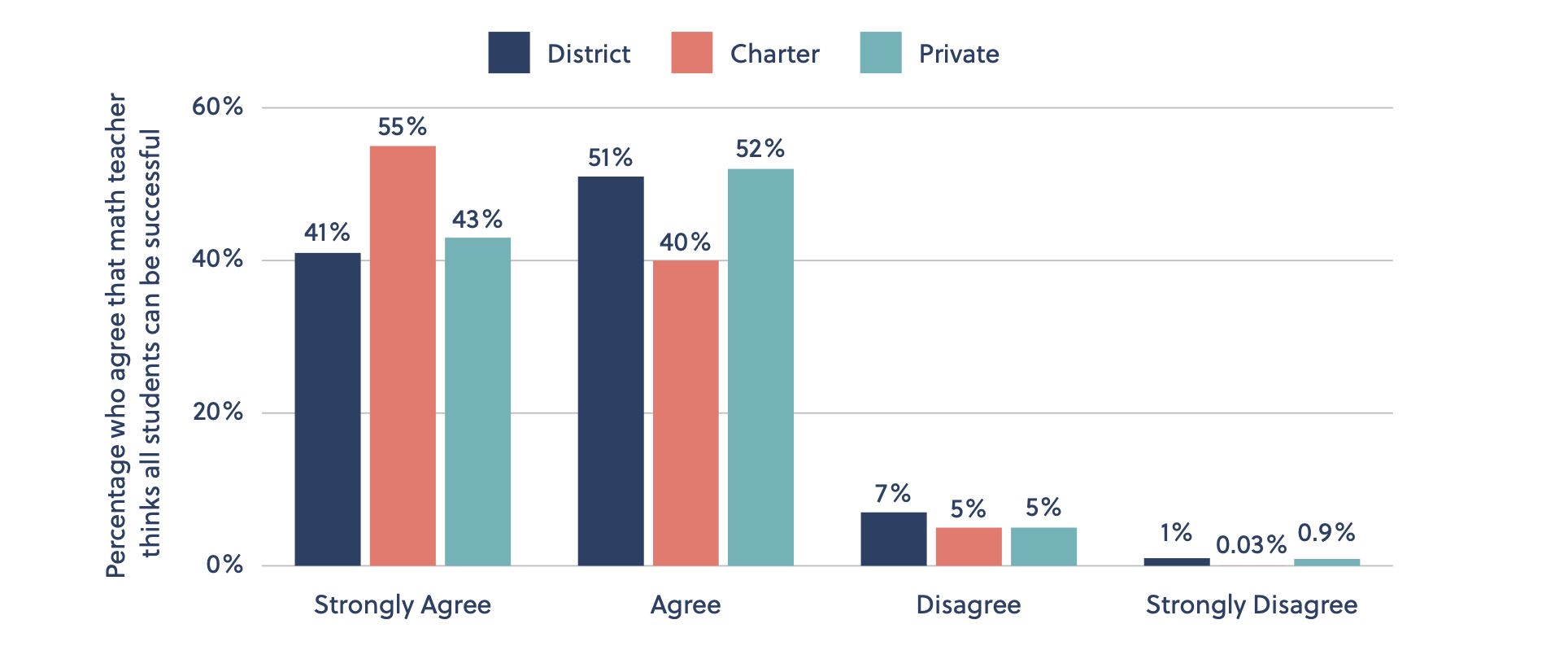

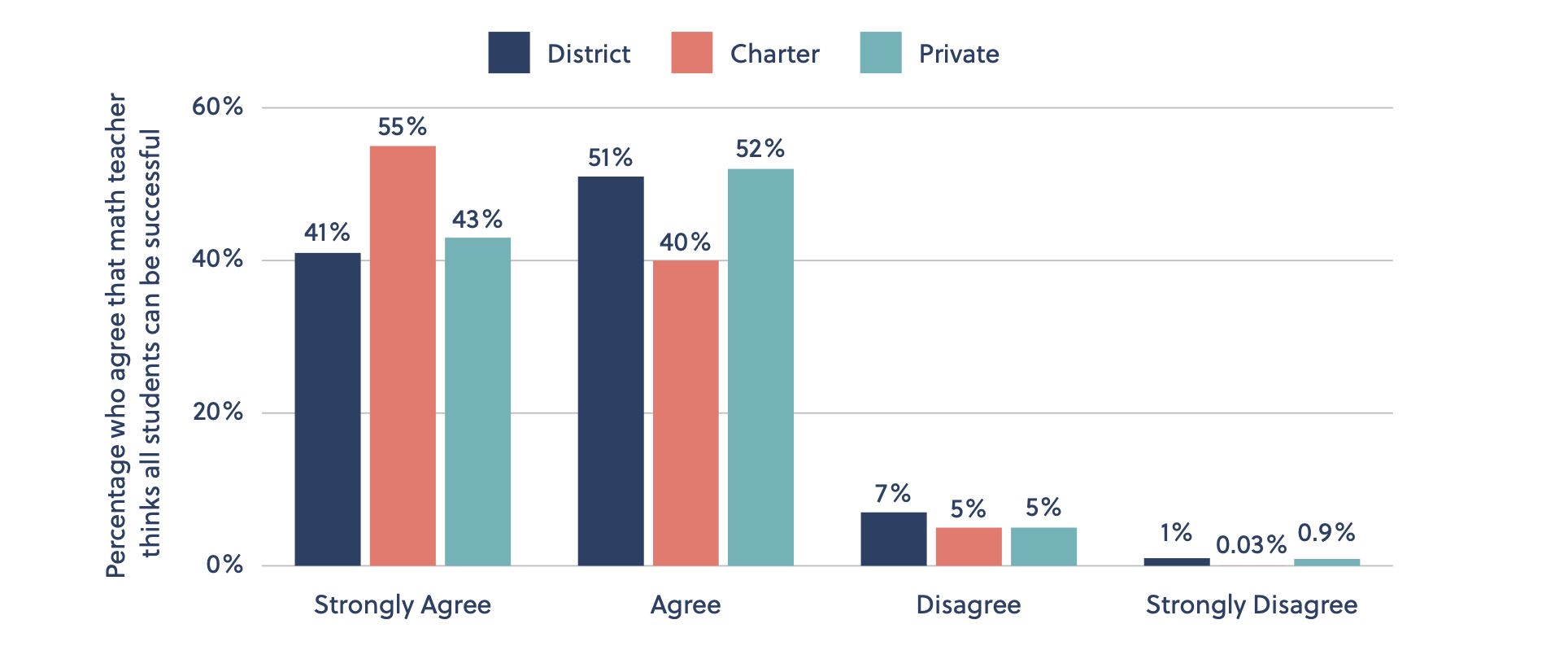

Finding 3: Students in charter and private schools are more likely than their district counterparts to believe that their teachers think “all students can be successful.”

Like teachers’ actual expectations, students’ perceptions of teachers’ expectations seem to differ by sector (though they are generally not statistically significant at traditional confidence levels). For example, charter students were fourteen percentage points likelier than their traditional public school counterparts to “strongly agree” with the statement that their math teacher “thinks all students can be successful” (Figure 4). Moreover, like sectoral differences in teacher expectations, sectoral differences in students’ perceptions of teacher beliefs are not driven by observable differences between students and schools (see Appendix D, Table D3).

Figure 4. Students in charter and private schools are more likely than their district counterparts to believe that their teachers think “all students can be successful.”

Note: This figure shows the percentage of ninth graders who strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “My math teacher thinks all students can be successful,” separately by school sector.

Note: This figure shows the percentage of ninth graders who strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “My math teacher thinks all students can be successful,” separately by school sector. Intuitively, if students aren’t convinced that their teachers believe in all students’ ability to succeed, then at least some students may feel that their teacher doesn’t believe in them personally.

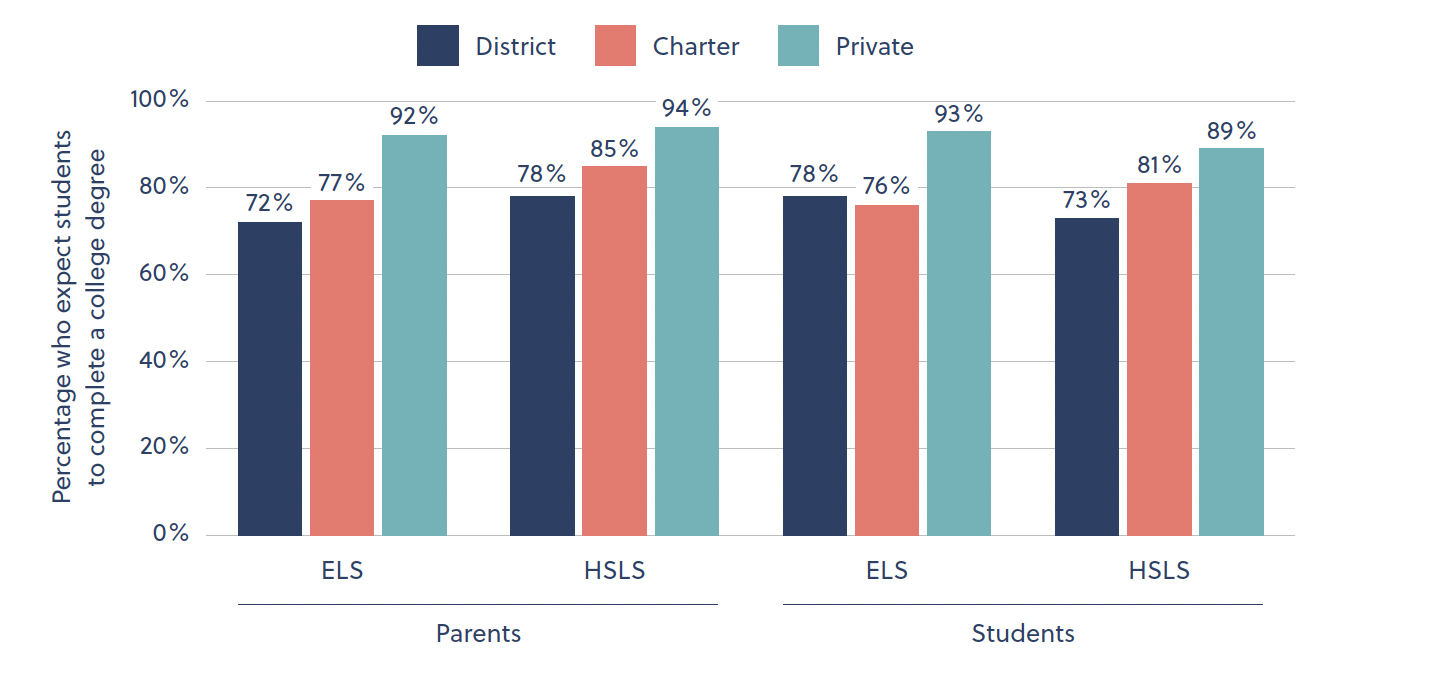

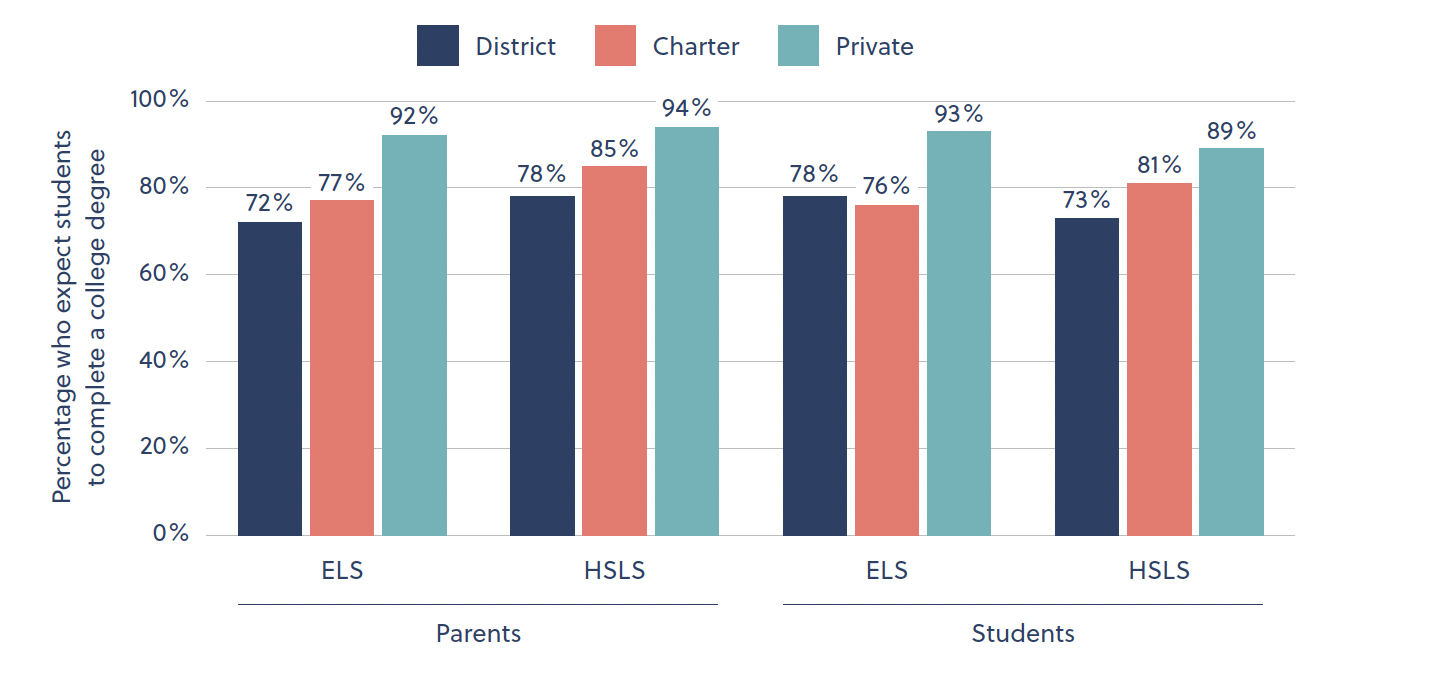

Figure 5. In general, students and parents in charter and private schools have higher college-completion expectations than their counterparts in traditional public schools.

Note: This figure shows the percentage of ELS and HSLS students (and parents) who expected that they (or their child) would earn a four-year college degree (or more) separately by school sector.

Note: This figure shows the percentage of ELS and HSLS students (and parents) who expected that they (or their child) would earn a four-year college degree (or more) separately by school sector. Like the differences in teachers’ expectations, these sectoral differences generally remain even after adjusting for student and school characteristics (Tables D4 and D5 in Appendix D). What accounts for these differences is less clear. For example, changing parent and/or student expectations is one of several plausible channels through which teacher expectations could affect students’ long-run outcomes.[38] However, parent and student expectations could be shaped by the same school culture and leadership attributes that shape teacher expectations—as well as by unobserved differences in motivation and preferences for educational attainment.

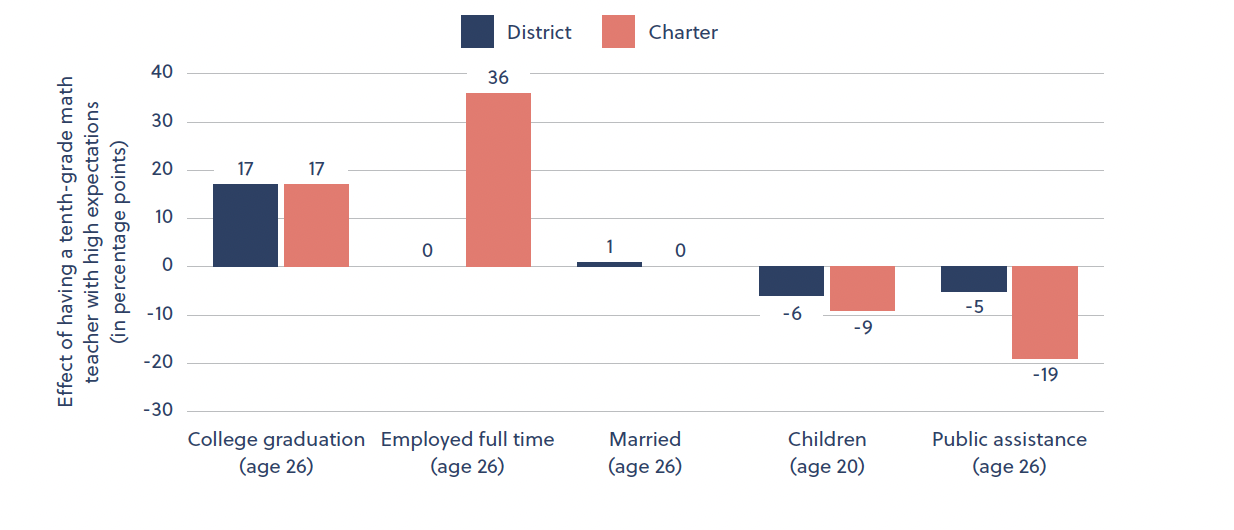

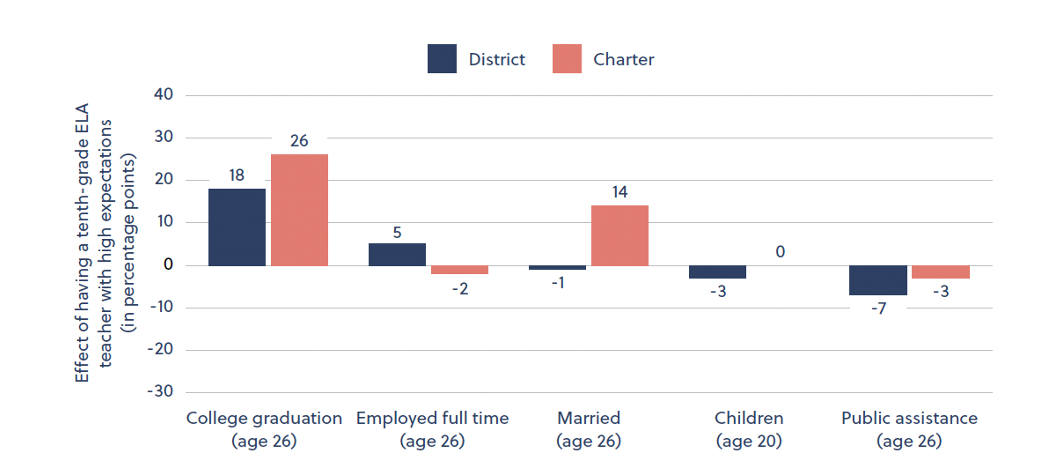

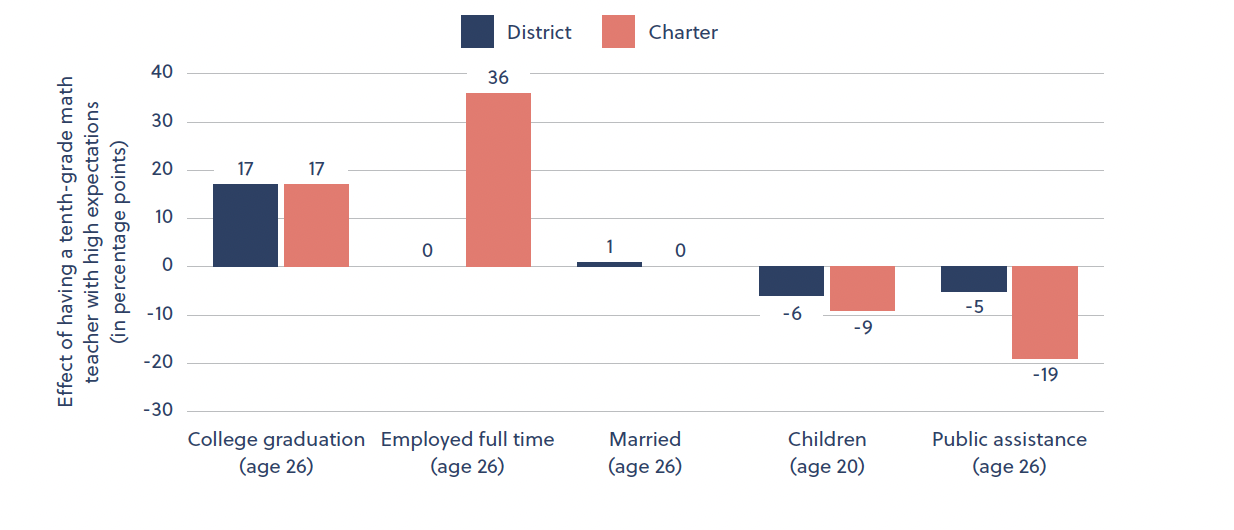

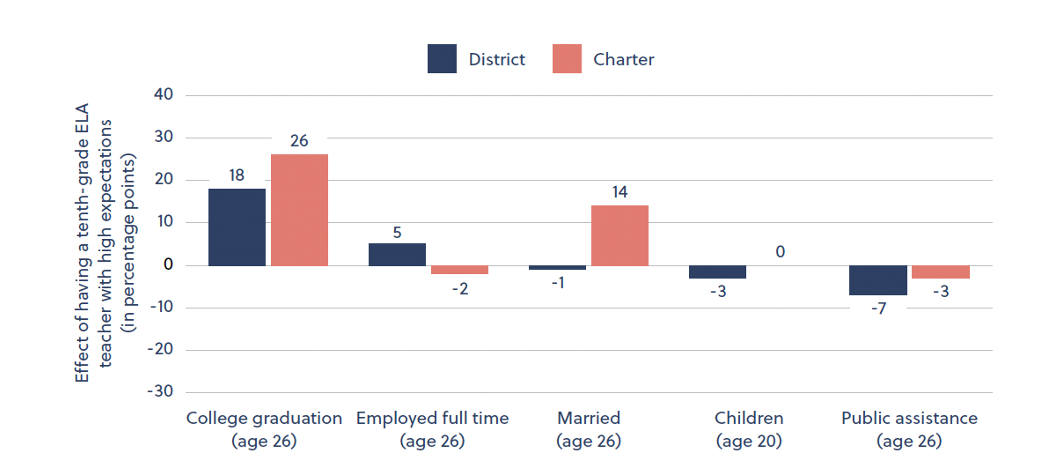

Finding 4: Regardless of sector, teacher expectations have a positive effect on long-run outcomes, such as college completion, teen childbearing, and receipt of public assistance.

Regardless of sector, high school teachers’ expectations that students will earn college degrees have a positive effect on at least three of the five long-run outcomes that we consider (Figure 6). For example, regardless of whether the teacher and student are in a traditional public school or a charter school, having a math teacher who fully expects a student to obtain a college degree (relative to one who thinks the student has no chance) boosts that student’s odds of college completion by about seventeen percentage points. Similarly, high teacher expectations for their students’ education reduce the chances that students will have children before the age of twenty by about three to six percentage points and reduce their probability of receiving public assistance at age twenty-six by approximately five percentage points. However, we don’t see similar impacts on the likelihood of marriage or employment (by age twenty-six).

For some outcomes (like employment), there is suggestive evidence that the effect of high teacher expectations may be bigger in charter schools (though due to small sample sizes, these differences aren’t statistically significant). In other words, the evidence suggests that the effects of high expectations are at least as big in charter schools as they are in traditional public schools.

Figure 6. Regardless of sector, high teacher expectations have a positive effect on at least three long-term outcomes of interest.

A. Effects of math teachers’ expectations

B. Effects of English teachers’ expectations

Note: These figures show the estimated effect on five long-term outcomes of having a tenth-grade math or English teacher who fully expects students to obtain at least a four-year college degree. The actual regression estimates are reported in Tables D6 and D7 of Appendix D.

Note: These figures show the estimated effect on five long-term outcomes of having a tenth-grade math or English teacher who fully expects students to obtain at least a four-year college degree. The actual regression estimates are reported in Tables D6 and D7 of Appendix D.Although some of these estimates may seem implausibly large, their magnitude is at least partly a consequence of the binary nature of the independent variable. Because of this feature of the data, what the estimates in Figure 6 capture is the effect of replacing a teacher who has zero faith in their student’s ability to complete a college degree with one who is certain that the student will do so. But of course, this scenario is unrealistic, so it makes more sense to imagine the effects of a more marginal change. For example, what would happen if a student’s teacher changed their confidence in the student’s ability to complete a college degree by twenty-five percentage points (e.g., from 50 percent to 75 percent confident)?

Roughly speaking, the estimates in Figure 6 imply that such a twenty-five-percentage-point increase in a teacher’s confidence increases the probability that a student will actually complete a four-year college degree by about 4.2 percentage points. Given that about 45 percent of the sample completed a college degree, this represents an increase of nearly 10 percent.[39]

Takeaways

Takeaways

Teacher expectations are higher in charter schools than in traditional public schools, even after accounting for sectoral differences in student and school characteristics. They’re highest in private schools, which is unsurprising given the “college-prep” aura of many private high schools, as well as their selected student body, plus the material advantages common to many of their pupils. What’s more, teacher expectations matter just as much, if not more, in charter schools as they do in traditional public schools. In other words, the data suggest that charter schools have an unambiguous “expectations advantage” over traditional public schools.

These results have at least three implications for policy and practice.

First, policymakers should continue to give charter schools flexibility to keep doing what they’re doing with respect to hiring and developing teachers who believe that all students can succeed. For example, prior research suggests that charter schools have more Black teachers than traditional public schools—in part due to relaxed certification requirements—and that the effects of “race match” are particularly large in charter schools.[40] This presumably leads to higher average expectations in charter schools that enroll nontrivial shares of non-White students, since White teachers tend to have lower expectations for students of color than for White students, all else being equal.[41] Similarly, many alternative certification programs, such as Teach For America, explicitly focus on and succeed in producing teachers who truly possess high expectations for all students.[42]

Second, education researchers and leaders of traditional public schools should try to learn from charter schools’ success on this front. After all, it may be that teachers’, parents’, and students’ expectations for the future are all driven by aspects of school culture that are theoretically transferrable (e.g., unusually strong school leadership or “college talk”).

Finally, concrete actions should be taken to ensure that as many teachers as possible do, in fact, have and espouse high expectations for their students. One way to approach this is in the hiring process (i.e., by treating high expectations as a teacher characteristic for which to select). For example, schools might try to hire from training programs known to emphasize high expectations for all or address the question during the interview process. However, schools and districts should also consider how they might boost the expectations of their existing teacher force—for example, by incorporating student surveys that include an “expectations” dimension into their teacher-evaluation systems, by adopting light-touch professional-development interventions that increase teachers’ empathy and expectations for students, or by making them aware of this research.

Endnotes

[14] Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson, “Pygmalion in the classroom,” The Urban Review 3, no. 1 (1968): 16–20, doi:10.1007/BF02322211.

[15] Julia Chabrier, Sarah Cohodes, and Philip Oreopoulos, “What Can We Learn from Charter School Lotteries?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no. 3 (2016): 57–84, doi:10.1257/jep.30.3.57; Roland G. Fryer, Jr., “Injecting Charter School Best Practices into Traditional Public Schools: Evidence from Field Experiments,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 3 (2014): 1355–407, doi:10.1093/qje/qju011.

[16] Joshua D. Angrist et al., “Inputs and impacts in charter schools: KIPP Lynn,” American Economic Review 100, no. 2 (2010): 239–43, doi:10.1257/aer.100.2.239; Sarah Cohodes, Charter Schools and the Achievement Gap (Princeton, NJ: The Future of Children, 2018), https://futureofchildren.princeton.edu/sites/futureofchildren/files/resource-links/charter_schools_compiled.pdf; Philip M. Gleason et al., “Do KIPP Schools Boost Student Achievement?” Education Finance and Policy 9, no. 1 (2014): 36–58, doi:10.1162/EDFP_a_00119.

[17] Philip M. Gleason, “What’s the secret ingredient? Searching for policies and practices that make charter schools successful,” Journal of School Choice 11, no. 4 (2017): 559–84, doi:10.1080/15582159.2017.1395620.

[18] Nicholas W. Papageorge, Seth Gershenson, and Kyung Min Kang, “Teacher Expectations Matter,” Review of Economics and Statistics 102, no. 2 (2020): 234–51, doi:10.1162/rest_a_00838.

[21] Nicholas W. Papageorge, Seth Gershenson, and Kyung Min Kang, “Teacher Expectations Matter,” Review of Economics and Statistics 102, no. 2 (2020): 234–51, doi:10.1162/rest_a_00838; Andrew J. Hill and Daniel B. Jones, “Self-Fulfilling Prophecies in the Classroom,” Journal of Human Capital 15, no. 3 (2021): 400–31, doi:10.1086/715204; David N. Figlio and Maurice E. Lucas, “D Do High Grading Standards Affect Student Performance?” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9–10 (2004): 1815–34, doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00039-2; and Seth Gershenson, Great Expectations: The Impact of Rigorous Grading Practices on Student Achievement (Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2020), https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/great-expectations-impact-rigorous-grading-practices-student-achievement.

[22] Nicole M. Fortin, Philip Oreopoulos, and Shelley Phipps, “Leaving Boys Behind: Gender Disparities in High Academic Achievement,” Journal of Human Resources 50, no. 3 (2015): 549–79, doi:10.3368/jhr.50.3.549.

[26] Lee Jussim and Kent D. Harber, “Teacher Expectations and Self-Fulfilling Prophecies: Knowns and Unknowns, Resolved and Unresolved Controversies,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 9, no. 2 (2005): 131–55, doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3.

[27] Papageorge, Gershenson, and Kang, “Teacher Expectations Matter”; and Hill and Jones, “Self-Fulfilling Prophecies in the Classroom.”

[28] Hill and Jones, “Self-Fulfilling Prophecies in the Classroom.”

[29] Still, the degree to which White teachers are overly optimistic is significantly larger for White students than for Black students. See Papageorge, Gershenson, and Kang, “Teacher Expectations Matter.”

[30] Julia Chabrier, Sarah Cohodes, and Philip Oreopoulos, “What Can We Learn from Charter School Lotteries?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no. 3 (2016): 57–84, doi:10.1257/jep.30.3.57; and Roland G. Fryer, Jr., “Injecting Charter School Best Practices into Traditional Public Schools: Evidence from Field Experiments,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 3 (2014): 1355–407, doi:10.1093/qje/qju011.

[31] Joshua D. Angrist et al., “Inputs and impacts in charter schools: KIPP Lynn,” American Economic Review 100, no. 2 (2010): 239–43, doi:10.1257/aer.100.2.239; Sarah Cohodes, Charter Schools and the Achievement Gap (Princeton, NJ: The Future of Children, 2018), https://futureofchildren.princeton.edu/sites/futureofchildren/files/resource-links/charter_schools_compiled.pdf; and Philip M. Gleason et al., “Do KIPP Schools Boost Student Achievement?” Education Finance and Policy 9, no. 1 (2014): 36–58, doi:10.1162/EDFP_a_00119.

[32] Philip M. Gleason, “What’s the secret ingredient? Searching for policies and practices that make charter schools successful,” Journal of School Choice 11, no. 4 (2017): 559–84, doi:10.1080/15582159.2017.1395620.

[35] This is the same identification strategy used—and cross validated by a structural measurement error model—by Papageorge, Gershenson, and Kang (2020).

[36] Specifically, we measure sectoral gaps using the estimated coefficients on charter and private school indicators from regressions that control (or don’t control) for a host of student and school covariates, including school size (enrollment), the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, mother’s educational attainment, family income, language spoken at home, and standardized math score from ninth grade. This argument is similar in spirit to bounding approaches to selection on unobservables—e.g., the following: Joseph G. Altonji, Todd E. Elder, and Christopher R. Taber, “Selection on Observed and Unobserved Variables: Assessing the Effectiveness of Catholic Schools,” Journal of Political Economy 113, no. 1 (2005): 151–84, doi:10.1086/426036.

[37] Papageorge, Gershenson, and Kang, “Teacher Expectations Matter.”

[39] The figure of 45 percent is likely higher than in reality due to attrition and missing data in the sample.

[41] Seth Gershenson, Stephen B. Holt, and Nicholas W. Papageorge, “Who believes in me? The effect of student-teacher demographic match on teacher expectations,” Economics of Education Review 52 (2016): 209–24, doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002.

[42] Will Dobbie and Roland G. Fryer, Jr., “The Impact of Voluntary Youth Service on Future Outcomes: Evidence from Teach For America,” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 15, no. 3 (2015): 1031–65, doi:10.1515/bejeap-2014-0187.

About this study

This report was made possible through the generous support of the Walton Family Foundation, the Louis Calder Foundation, and our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. In addition to those institutions, we are grateful to Andrew Hill, Associate Professor at Montana State University, and Brian Kisida, Assistant Professor at the University of Missouri, for their timely and lucid feedback. We also extend our gratitude to Pamela Tatz for copyediting and Dave Williams for designing the figures and tables. At Fordham, we would like to thank Chester E. Finn, Jr. and Michael J. Petrilli for reviewing drafts; William Rost for handling funder communications; Victoria Sears for her role in dissemination; Lilly Sibel for developing the report’s cover art and coordinating the release; and Jeanette Luna for her assistance at various stages in the process.